Cotswold Cottage: From English Village to Greenfield Village

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052

The home was just as quaint inside—large open fireplaces with the mantels supported on oak beams. Heavy oak beams graced the ceilings and the roof. Spiral stone staircases led to the second floor. Morton bought the house and the two acres on which it stood under his own name from Margaret Smith in April 1929 for approximately $5000. Ford’s name was kept quiet. Had the seller been aware that the actual purchaser was Henry Ford, the asking price might have been higher.

Cotswold Cottage (probably built about 1619) as it looked when Herbert Morton spotted it, 1929–1930. / THF236020

“Perfecting” the Cotswold Look

Over the next several months, Herbert Morton and Frank Campsall, Ford’s personal secretary, traded correspondence concerning repairs and (with the best of intentions on Ford’s part) some “improvements” Ford wanted done to the building: the addition of architectural features that best exemplified the Cotswold style. Morton sent sketches, provided by builder and contractor W. Cox-Howman from nearby Stow-on-the-Wold, showing typical Cotswold architectural features not already represented in the cottage from which to choose. Ford selected the sketch which offered the largest number of typical Cotswold features.

Ford’s added features on the left cottage included a porch (a copy of one in the Cotswold village of Rissington), a dormer window, a bay window, and a beehive oven.

Cotswold Cottage, 1929–1930, showing modifications requested by Henry Ford: the beehive oven, porch, and dormer window. / THF235980

Bay window added to the left cottage by Henry Ford (shown 1929–1930). Iron casement windows were added throughout. / THF236054

The cottage on the right got a doorway “makeover” and some dove-holes. These holes are commonly found in the walls of barns, but not in houses. It would have been rather unappealing to have bird droppings so near the house!

Ford’s modifications to the right cottage—a new doorway (top) and dove-holes (bottom) on the upper wall. / THF236004, THF235988

Cotswold Cottage, now sporting Henry Ford’s desired alterations. / THF235984

Ford wanted the modifications completed before the building was disassembled—perhaps so that he could establish the final “look” of the cottage, as well as be certain that there were sufficient building materials. The appearance of the house now reflected both the early 1600s and the 1920s—each of these time periods became part of the cottage’s history. Ford’s additions, though not original to the house, added visual appeal.

The modifications were completed by early October 1929. The land the cottage stood on was transferred to the Ford Motor Company and later sold.

Cotswold Cottage Comes to America

Cotswold Cottage being disassembled. / THF148471

By January 1930, the dismantling of the modified cottage was in process. To carry out the disassembly, Morton again hired local contractor W. Cox-Howman.

Building components being crated for shipment to the United States. / THF148475

Doors, windows, staircases, and other architectural features were removed and packed in 211 crates.

Cotswold building stones ready for shipment in burlap sacks. / THF148477

The building stones were placed in 506 burlap sacks.

Cotswold barn and stable on original site, 1929–1930. / THF235974

The adjacent barn and stable, as well as the fence, were also dismantled and shipped along with the cottage.

Hauled by a Great Western Railway tank engine, 67 train cars transported the materials from the Cotswolds to London to be shipped overseas. / THF132778

The disassembled cottage, fence, and stable—nearly 500 tons worth—were ready for shipment in late March 1930. The materials were loaded into 67 Great Western Railway cars and transported to Brentford, west London, where they were carefully transferred to the London docks. From there, the Cotswold stones crossed the Atlantic on the SS London Citizen.

As one might suspect, it wasn’t a simple or inexpensive move. The sacks used to pack many of the stones were in rough condition when they arrived in New Jersey—at 600 to 1200 pounds per package, the stones were too heavy for the sacks. So, the stones were placed into smaller sacks that were better able to withstand the last leg of their journey by train from New Jersey to Dearborn. Not all of the crates were numbered; some that were had since lost their markings. One package went missing and was never accounted for—a situation complicated, perhaps, by the stones having been repackaged into smaller sacks.

Despite the problems, all the stones arrived in Dearborn in decent shape—Ford’s project manager/architect, Edward Cutler, commented that there was no breakage. Too, Herbert Morton had anticipated that some roof tiles and timbers might need to be replaced, so he had sent some extra materials along—materials taken from old cottages in the Cotswolds that were being torn down.

Cotswold “Reborn”

In April 1930, the disassembled Cotswold Cottage and its associated structures arrived at Greenfield Village. English contractor Cox-Howman sent two men, mason C.T. Troughton and carpenter William H. Ratcliffe, to Dearborn to help re-erect the house. Workers from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant also came to assist. Reassembling the Cotswold buildings began in early July, with most of the work completed by late September. Henry Ford was frequently on site as Cotswold Cottage took its place stone-by-stone in Greenfield Village.

Before the English craftsmen returned home, Clara Ford arranged a special lunch at the cottage, with food prepared in the cottage’s beehive oven. The men also enjoyed a sight-seeing trip to Niagara Falls before they left for England in late November.

By the end of July 1930, the cottage walls were nearly completed. / THF148485

On August 20, 1930, the buildings were ready for their shingles to be put in place. The stone shingles were put up with copper nails, a more modern method than the wooden pegs originally used. / THF148497

Cotswold barn, stable, and dovecote, photographed by Michele Andonian. / THF53508

Free-standing dovecotes, designed to house pigeons or doves which provided a source of fertilizer, eggs, and meat, were not associated with buildings such as Cotswold Cottage. They were found at the homes of the elite. Still, for good measure, Ford added a dovecote to the grouping about 1935. Cutler made several plans and Ford chose a design modeled on a dovecote in Chesham, England.

Henry and Clara Ford Return to the Cotswolds

The Lygon Arms in Broadway, where the Fords stayed when visiting the Cotswolds. / THF148435, detail

As reconstruction of Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village was wrapping up in the fall of 1930, Henry and Clara Ford set off for a trip to England. While visiting the Cotswolds, the Fords stayed at their usual hotel, the Lygon Arms in Broadway, one of the most frequently visited of all Cotswold villages.

Henry (center) and Clara Ford (second from left) visit the original site of Cotswold Cottage, October 1930. / THF148446, detail

While in the Cotswolds, Henry Ford unsurprisingly asked Morton to take him and Clara to the site where the cottage had been.

Cotswold village of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1930. / THF148440, detail

At Stow-on-the-Wold, the Fords called on the families of the English mason and carpenter sent to Dearborn to help reassemble the Cotswold buildings.

Village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds. / THF148437, detail

During this visit to the Cotswolds, the Fords also stopped by the village of Snowshill, not far from Broadway, where the Fords were staying. Here, Henry Ford examined a 1600s forge and its contents—a place where generations of blacksmiths had produced wrought iron farm equipment and household objects, as well as iron repair work, for people in the community.

The forge on its original site at Snowshill, 1930. / THF146942

A few weeks later, Ford purchased the dilapidated building. He would have it dismantled, and then shipped to Dearborn in February 1931. The reconstructed Cotswold Forge would take its place near the Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village.

To see more photos taken during Henry and Clara Ford’s 1930 tour of the Cotswolds, check out this photograph album in our Digital Collections.

Cotswold Cottage Complete in Greenfield Village—Including Wooly “Residents”

Completed the previous fall, Cotswold Cottage is dusted with snow in this January 1931 photograph. Cotswold sheep gather in the barnyard, watched over by Rover, Cotswold’s faithful sheepdog. (Learn Rover's story here.) / THF623050

A Cotswold sheep (and feline friend) in the barnyard, 1932. / THF134679

Beyond the building itself, Henry Ford brought over Cotswold sheep to inhabit the Cotswold barnyard. Sheep of this breed are known as Cotswold Lions because of their long, shaggy coats and faintly golden hue.

Cotswold Cottage stood ready to welcome—and charm—visitors when Greenfield Village opened to the public in June 1933. / THF129639

By the Way: Who Once Lived in Cotswold Cottage?

Cotswold Cottage, as it looked in the early 1900s. From Old Cottages Farm-Houses, and Other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District, 1905, by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber. / THF284946

Before Henry Ford acquired Cotswold Cottage for Greenfield Village, the house had been lived in for over 300 years, from the early 1600s into the late 1920s. Many of the rapid changes created by the Industrial Revolution bypassed the Cotswold region and in the 1920s, many area residents still lived in similar stone cottages. In previous centuries, many of the region’s inhabitants had farmed, raised sheep, worked in the wool or clothing trades, cut limestone in the local quarries, or worked as masons constructing the region’s distinctive stone buildings. Later, silk- and glove-making industries came to the Cotswolds, though agriculture remained important. By the early 1900s, tourism became a growing part of the region’s economy.

A complete history of those who once occupied Greenfield Village’s Cotswold Cottage is not known, but we’ve identified some of the owners since the mid-1700s. The first residents who can be documented are Robert Sley and his wife Mary Robbins Sley in 1748. Sley was a yeoman, a farmer who owned the land he worked. From 1790 at least until 1872, Cotswold was owned by several generations of Robbins descendants named Smith, who were masons or limeburners (people who burned limestone in a kiln to obtain lime for mixing with sand to make mortar).

As the Cotswold region gradually evolved over time, so too did the nature of some of its residents. From 1920 to 1923, Austin Lane Poole and his young family owned the Cotswold Cottage. Medieval historian, fellow, and tutor at St. John’s College at Oxford University (about 35 miles away), Poole was a scholar who also enjoyed hands-on work improving the succession of Cotswold houses that he owned. Austin Poole had gathered documents relating to the Sley/Robbins/Smith families spanning 1748 through 1872. It was these deeds and wills that revealed the names of some of Cotswold Cottage’s former owners. In 1937, after learning that the cottage had been moved to Greenfield Village, Poole gave these documents to Henry Ford.

In 1926, Margaret Cannon Smith purchased the house, selling it in 1929 to Herbert Morton, on Henry Ford’s behalf.

“Olde English” Captures the American Imagination

At the time that Henry Ford brought Cotswold Cottage to Greenfield Village, many Americans were drawn to historic English architectural design—what became known as Tudor Revival. The style is based on a variety of late Middle Ages and early Renaissance English architecture. Tudor Revival, with its range of details reminiscent of thatched-roof cottages, Cotswold-style homes, and grand half-timbered manor houses, became the inspiration for many middle-class and upper-class homes of the 1920s and 1930.

These picturesque houses filled suburban neighborhoods and graced the estates of the wealthy. Houses with half-timbering and elaborate detail were often the most obvious examples of these English revival houses, but unassuming cottage-style homes also took their place in American towns and cities. Mansion or cottage, imposing or whimsical, the Tudor Revival house was often made of brick or stone veneer, was usually asymmetrical, and had a steep, multi-gabled roof. Other characteristics included entries in front-facing gables, arched doorways, large stone or brick chimneys (often at the front of the house), and small-paned casement windows.

Edsel Ford’s home at Gaukler Pointe, about 1930. / THF112530

Henry Ford’s son Edsel and his wife Eleanor built their impressive but unpretentious home, Gaukler Pointe, in the Cotswold Revival style in the late 1920s.

Postcard, Postum Cereal Company office building in Battle Creek, Michigan, about 1915. / THF148469

Tudor Revival design found its way into non-residential buildings as well. The Postum Cereal Company (now Post Cereals) of Battle Creek, Michigan, chose to build an office building in this centuries-old English style.

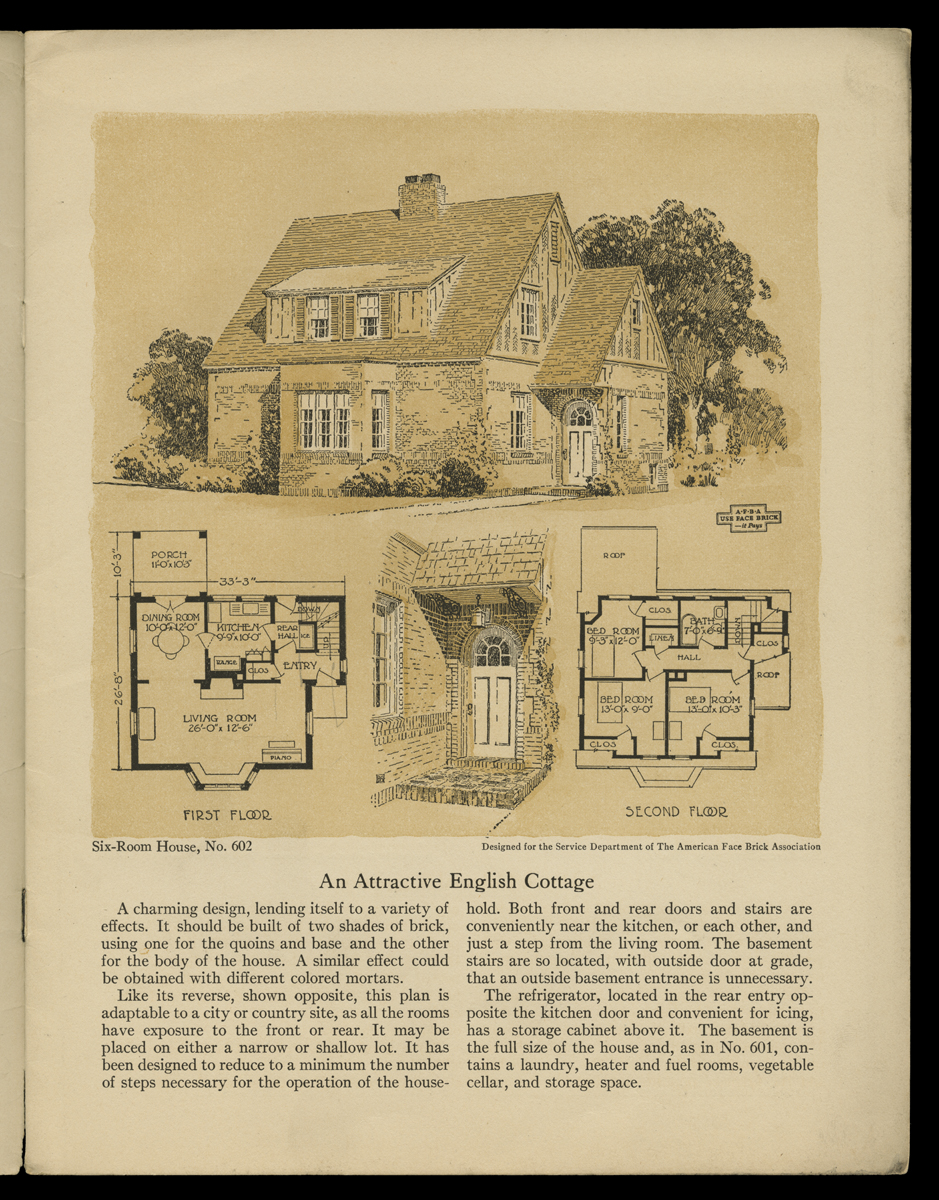

Plan for “An Attractive English Cottage” from the American Face Brick Association plan book, 1921. / THF148542

Plans for English-inspired homes offered by Curtis Companies Inc., 1933. / THF148549, THF148550, THF148553

Tudor Revival homes for the middle-class, generally more common and often smaller in size, appeared in house pattern books of the 1920s and 1930s.

Sideboard, part of a dining room suite made in the English Revival style, 1925–1930. / THF99617

The Tudor Revival called for period-style furnishings as well. “Old English” was one of the most common designs found in fashionable dining rooms during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christmas card, 1929. / THF4485

Even English-themed Christmas cards were popular.

Cotswold Cottage—A Perennial Favorite

Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF53489

Henry Ford was not alone in his attraction to the distinctive architecture of the Cotswold region and the English cottage he transported to America. Cotswold Cottage remains a favorite with many visitors to Greenfield Village, providing a unique and memorable experience.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Cotswold Cottage Tea

- Interior of Cotswold Cottage at its Original Site, Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England, 1929-1930

- Cotswold Cottage

home life, design, farm animals, travel, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller

Facebook Comments