Posts Tagged by jeanine head miller

What We Wore: Movie Costumes

Costume design is more than just providing clothes for actors in a movie. Effective costume design can reveal a character's background, personality, occupation, and even their state of mind. Each costume choice made by a designer—type and style of garment, accessories, details, materials, color—is deliberate, contributing to character development and the overall mood of the narrative.

The costumes below are from films directed by award-winning director Francis Ford Coppola. Coppola’s movies The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979) are often cited among the greatest films of all time.

Costumes provided by American Zoetrope

Through mid-December 2025, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents costumes from the film Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / THF805834

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

As Coppola began production on his spectacular reimagining of the 1897 Bram Stoker vampire novel, he declared that “the costumes will be the set.” His goal: visually exciting costumes that would establish the film’s surreal atmosphere. With the bulk of his budget slated for costumes, he turned to Japanese graphic designer Eiko Ishioka.

Eiko Ishioka, posing with the mask that pairs with Dracula’s armored suit.

Eiko Ishioka, Costume Designer

Eiko Ishioka was not known for costume design when Coppola hired her, a choice that might have seemed a risk. Yet Ishioka’s inventive, avant-guarde style was just what the film needed. And Coppola gave her free rein.

Ishioka—known for crossing or blurring boundaries—incorporated audacious forms, infused symbolic detail, and intertwined elements of Eastern and Western cultures along with steampunk aesthetics into the designs. Ishioka’s extravagant re-envisioning earned her an Academy Award for Best Costume Design.

Tom Waits as Renfield in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / Image by Columbia Pictures.

Renfield

R.M. Renfield—Dracula’s deranged, fanatically devoted servant—has gone insane and is confined to a mental hospital. Renfield suffers from delusions that compel him to eat insects and other living creatures in the hope of obtaining immortality.

The striped design of Renfield’s quilted straitjacket suggests his “prisoner” status. Constructed of rough gray fabric, the costume makes Renfield himself look like an insect!

Gary Oldman as Dracula in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / Image by Columbia Pictures.

Dracula

Ishioka wanted to suggest Dracula’s continued transformation, so she created seven distinctive—and often over-the-top—costumes for him. (In most Dracula-themed films, the fabled vampire had sported a single iconic look defined by a black swirling cape.)

Sometimes less is more. The slender, black pencil coat (shown above), the most visually understated of Ishioka’s Dracula costumes, conveys an ominous sense of undefined danger. While mildly deviant and somehow sinister, the garment provides no overt clues to Dracula’s disturbing need for drinking blood.

Winona Ryder as Elisabeta (later Mina Harker) in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / Image by Columbia Pictures.

Elisabeta

After being falsely informed that her husband Dracula was killed while off fighting in the Crusades, Elisabeta wears this stunning dress—emblazoned with Dracula’s crest of the Order of the Dragon—as she commits suicide by hurling herself from the castle parapet, setting in motion the Dracula-initiated tragedies to come.

Dracula transforms into a vampire as he waits for the return of his longed-for dead bride—who centuries later he believes is reincarnated in the form of intelligent, yet naïve, Mina Harker.

Earlier this year, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presented costumes from the film Megalopolis. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Megalopolis

Coppola envisioned Megalopolis as a fable, set in a modern world with references to ancient Rome. The deteriorating city of New Rome (New York City) is dominated by a group of elite families, who enjoy lavish lifestyles while ordinary New Romans live in poverty. New Rome must change—causing conflict. Cesar Catilina, a brilliant architect, offers a new vision for the city’s future, the utopian Megalopolis. Mayor Franklyn Cicero remains committed to a status quo of greed and special interests.

Milena Canonero. Image courtesy of Cineberg/Shutterstock.com

Milena Canonero, Costume Designer

Milena Canonero’s costumes for the futuristic Megalopolis reflect Coppola’s vision, merging contemporary design with elements from ancient Rome. A four-time Academy Award winner, the versatile Canonero has developed costumes for the dystopian classic A Clockwork Orange (1971), the psychological horror film The Shining (1980), and the period drama The Cotton Club (1984).

Jon Voight as Hamilton Crassus III in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Megalopolis (2024). / Image courtesy of Milena Canonero.

Hamilton Crassus III

Hamilton Crassus III, head of Crassus National Bank, is the world’s richest man. He can buy anything. With his health and mind in decline, he is easily manipulated by others who have their eyes on his money—and their own interests at heart.

Crassus has “bought” beautiful Wow Platinum—or so he thinks. Crassus’s attire for his wedding to the ambitious Wow shows his great wealth and vanity: a gold-embroidered tuxedo, a cape with lapels that suggest a rich vein of gold, and a gilded “laurel” wreath on his head.

Aubrey Plaza as Wow Platinum in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Megalopolis (2024). / Image courtesy of Milena Canonero.

Wow Platinum

Wow Platinum, a TV personality specializing in financial news, lives for money and power. Wow marries the extremely wealthy—and much older—Hamilton Crassus III. Her plan? To secure control of Crassus and his enormous wealth.

The unscrupulous Wow is a vision in gold in her elegant wedding dress and crown at the over-the-top wedding reception, a decadent celebration complete with circus acts and gladiator wrestling.

Giancarlo Esposito as Mayor Franklyn Cicero in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Megalopolis (2024). / Image courtesy of Milena Canonero.

Franklyn Cicero

Franklyn Cicero, the ultra-conservative mayor of New Rome, has an ineffectual plan for revitalizing the deteriorating city. He’s set his sights on building a casino for the city that will provide immediate tax revenue.

Cicero’s ceremonial formal attire reflects his exalted position as mayor. Yet he must fight to retain power as he spars with idealistic architect Cesar Catilina and his more positive vision—rebuilding New Rome as a utopia.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

What We Wore: Cocktail Party

Through mid-April 2025, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents fashionable 1950s cocktail attire. / THF802492

Cocktail parties were the essence of sophistication in the 1950s. Throwing a cocktail party — whether to impress business associates or entertain neighbors — was the “in” thing to do. The American economy was expanding, people were moving to the suburbs, and a return to traditional gender roles put women back in the home as full-time homemakers. Entertaining after work and on weekends became an essential part of business and neighborhood life. Hosts relished showing off their skills as they impressed guests with trendy cocktails and hors d'oeuvres.

Elegantly informal — and often, aspirational — cocktail parties were part of a "see and be seen" culture where every social event had a dress code. For cocktail parties, men wore a dark suit, white shirt, and a tie. Proper attire for women? Stylish semi-formal dresses with either full skirts or slender silhouettes — a polished look, but not overly extravagant.

Suit, 1948. Made by Guild Commander for The Hub department store, Baltimore, Maryland. / THF802440. Gift of American Textile History Museum, donated to ATHM by Robert M. Vogel.

Attending cocktail parties was a must to climb the corporate ladder.

Cocktail dress & jacket, about 1958. Ruth McCulloch, Hubbard Woods and Evanston, Illinois. / THF162635. Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis.

Cocktail dress, about 1952. Christian Dior, Paris, France. / THF29329. Gift of Mrs. Harvey Firestone, Jr.

French couture houses continued to dictate high fashion during the 1950s.

Cocktail dress, about 1959. Possibly made by Catherine Prindle Roddis, Marshfield, Wisconsin. / THF160845. Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis.

The “little black dress” has become a wardrobe essential — a simple, versatile, elegant dress that can be dressed up or down depending on the occasion.

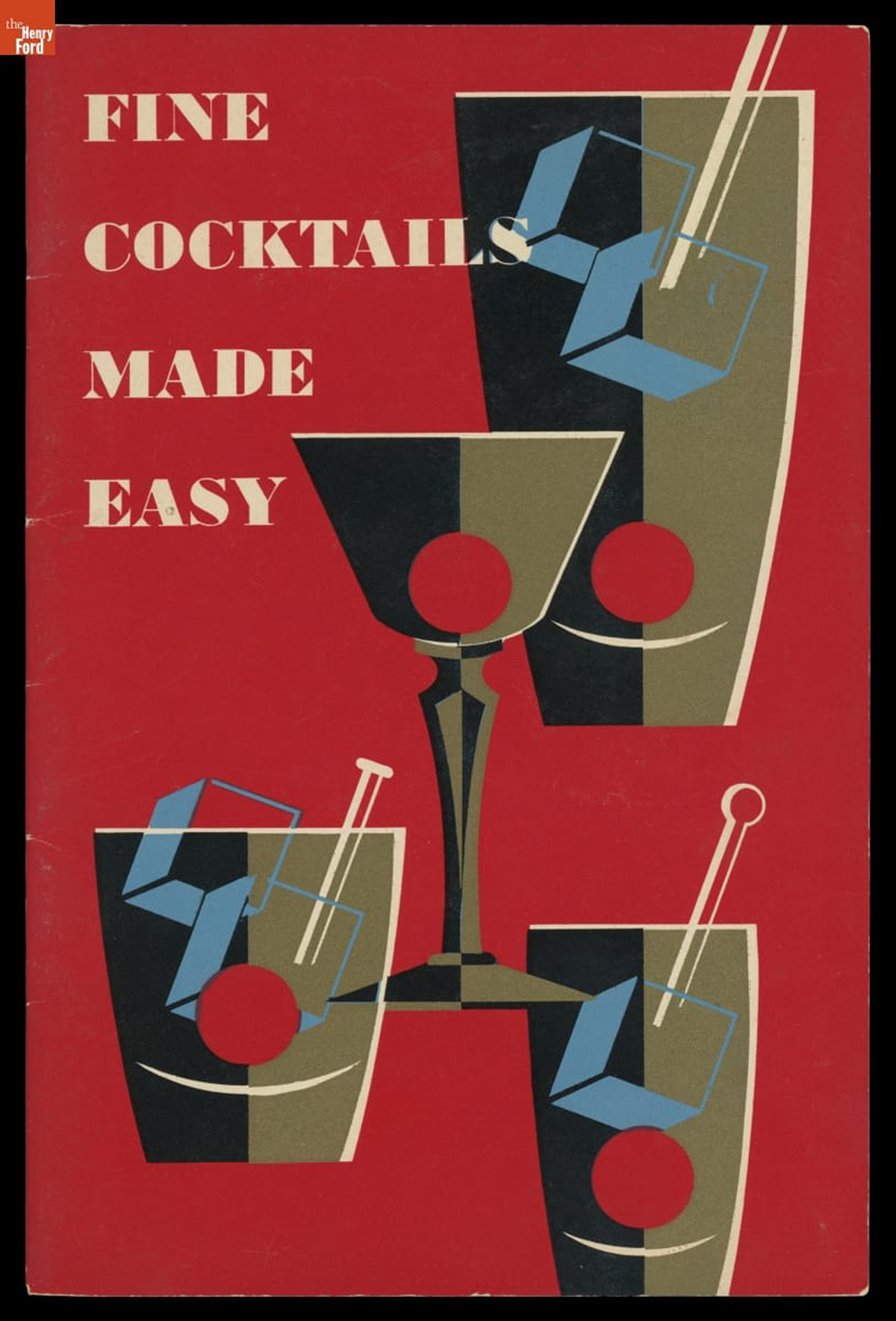

The right drinks and food helped guarantee cocktail party success. Handbooks provided helpful advice and recipes for eager hosts and hostesses. National Distillers Products Corporation, 1955-1960. / THF720273

Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

What We Wore: Off to Work We Go

Through mid-December 2024, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents work “fashions” — and a bit of work lives — of a postal carrier, fast food worker, nurse, flight attendant, and dairy delivery worker.

Work uniforms can denote an occupation, support a sense of unity and belonging, identify staff for customers, promote a brand, or even suggest trustworthiness.

Uniforms have changed over the years as fashion, fabrics, corporate identity, and gender roles have evolved.

Postal Carrier

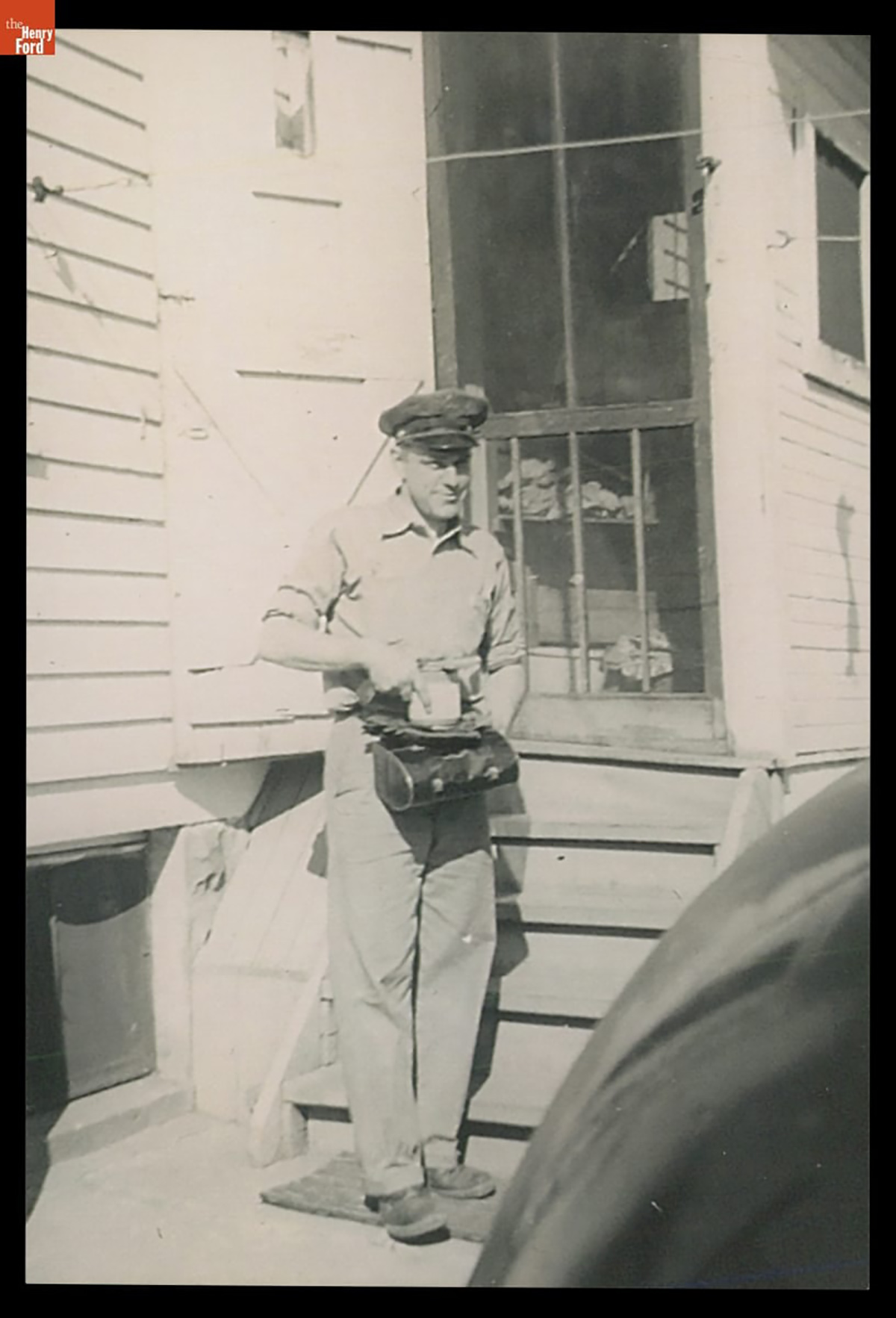

Postal carrier uniform and hat, 1955-1965. Worn by Herbert Temple Goltry of Allen Park, Michigan. / THF152804, THF152867

Uniforms worn by U.S. Postal Service carriers are designed for comfort and function. Created in regulation styles and colors — with some local variation — these uniforms are instantly recognizable and imply that the wearer is a trustworthy government employee. Carrier uniforms adopted the "Eisenhower jacket" look in 1953. This practical, yet smart, waist-length jacket, named after General Dwight D. Eisenhower, was developed for the U.S. Army during World War II. The eight-point cap — made with a woven cane band for ventilation — became the mandatory cap style for carriers beginning in 1955.

In 1913, the U.S. Post Office began Parcel Post, offering delivery service for packages weighing over 4 pounds to customers across the nation. Herbert Goltry, the wearer of this uniform, delivered parcel post packages from the 1940s into the 1970s. Post Office patch design and trouser stripe colors were changed from time to time and no longer appear on this uniform.

Herbert Goltry wearing a postal carrier's uniform, 1940-1945. / THF717914.

Postal carriers are known to spend a lot of time on their feet. These Jerk brand "Activ-8" elasticized support socks use the image of a postman as an “endorsement” of their product. 1955-1960. / THF196279

Fast Food Worker

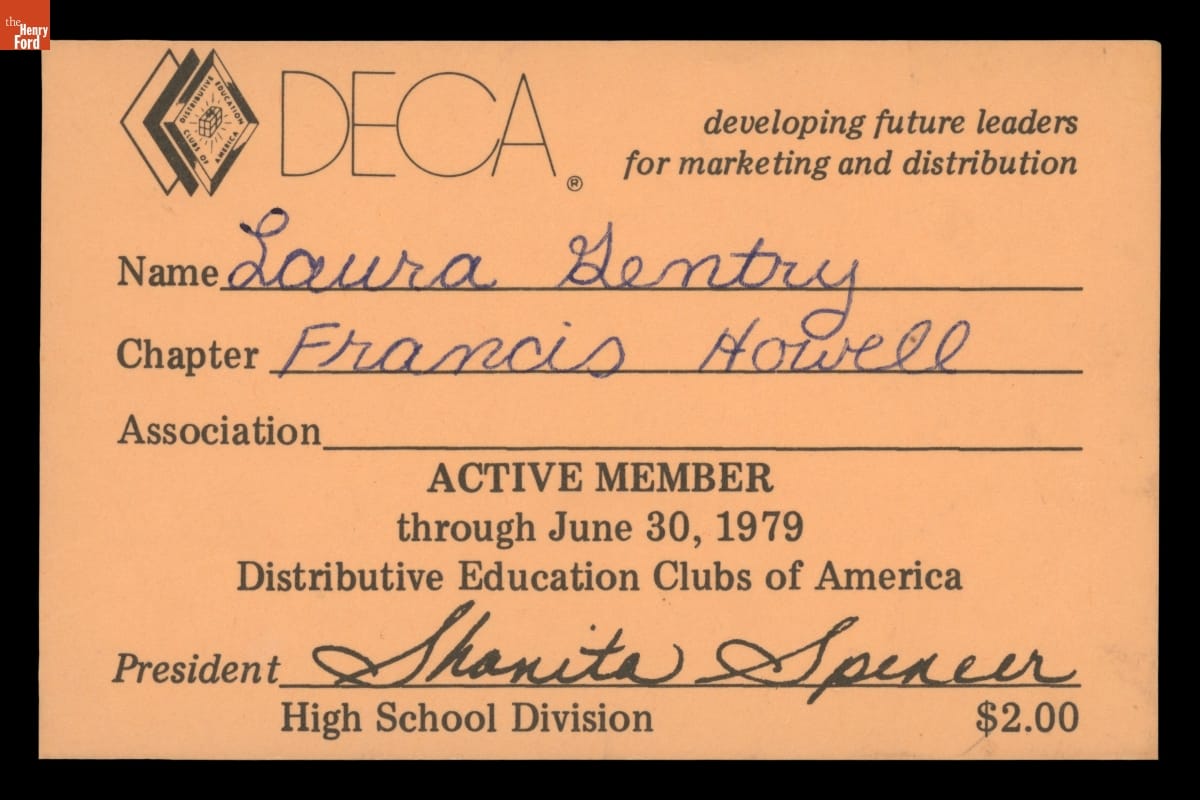

Dairy Queen uniform blouse, 1978. Worn by Laura Gentry of Harvester, Missouri. / THF372105 Gift of Laura (Gentry) Stupperich

A growing number of fast food restaurants have become part of the American landscape since the mid-20th century — jobs at these restaurants are often among a teen’s first. Wearing a uniform that represents the company's brand is part of the experience.

Laura Gentry worked at Dairy Queen in Harvester, Missouri, from her senior year in high school through college. She wore this distinctive uniform blouse — brown, red, and gold plaid — along with dark brown pants purchased on her own.

Laura dove in, preparing ice cream orders, dealing with customers, handling money, cleaning tables, and mopping floors. She loved making the iconic Dairy Queen curly twist on top of the soft-serve ice cream cones.

Laura's hard work earned her a management role at the restaurant while she attended college classes for a career in accounting. Her family had wanted her to go places. For Laura, her experiences at Dairy Queen paved the way.

Laura Gentry posed on her Halloween birthday in 1978--then headed off to her job at Dairy Queen! / THF718996 Gift of Laura (Gentry) Stupperich

When Laura Gentry and her Dairy Queen coworkers graduated from high school in 1979, the restaurant's sign took note. / THF718998 Gift of Laura (Gentry) Stupperich.

Laura Gentry's job at Dairy Queen was part of DECA, a program aimed at providing work experience for high school students. / THF719001 Gift of Laura (Gentry) Stupperich.

Nurse

Nurse's uniform, cape, and cap, 1957. Worn by Marie Goltry of Allen Park, Michigan. / THF371971, THF152866.

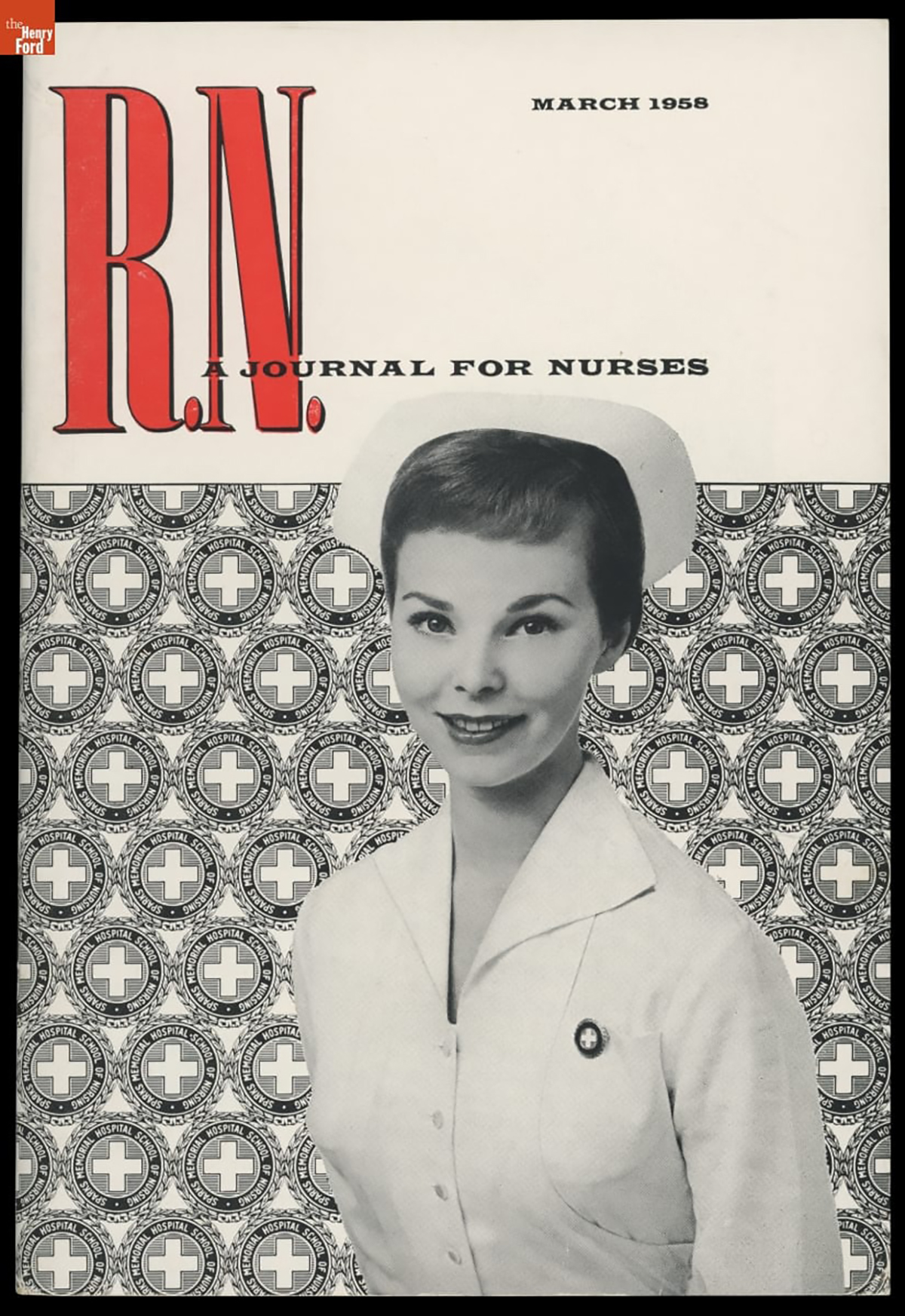

Nursing is a demanding job that requires specialized training — and until recent decades, it was predominantly a woman's profession. Marie Goltry was one of more than 5,000 nurses who graduated from the Henry Ford Hospital School of Nursing in Detroit during its 71 years of service. In the mid-20th century, college programs would begin to replace hospital-based education.

For decades, nurses' uniforms were white — in the early 1900s white was considered more sanitary and scientific. Nurses wore a crisp white dress, white cap, white hose, and sturdy white shoes. The uniform was reassuring to patients who knew their care was in the hands of a trained professional.

Wearing a white dress and cap — and keeping them spotless — was often impractical in a healthcare setting. By the 1980s, clothing for nurses took a more practical turn. Scrubs were easier to move in, keep clean, and came in fabrics that let the wearer express their individuality — and scrubs were gender neutral, as men joined the nursing profession.

Marie Goltry poses in her uniform after graduating from Henry Ford Hospital Nursing School in 1957. "Ford grads," like nurses who graduated from other training programs, were easily recognized by their unique caps. THF717912

Journals helped nurses learn of new developments in health and health care. R.N.: A Journal for Nurses, March 1958. THF719176

Flight Attendant

Trans World Airlines flight attendant uniform, 1965. Worn by Diane Beers of East Orange, New Jersey. / THF372094 Gift of Diane B. Hill.

In the 1960s, when flying was still an adventure for many, being a flight attendant — or stewardess as they were then known — offered an exciting career choice for young women. Winging one's way to destinations across the country or around the globe had great appeal.

In an era when most airline travelers were men, most flight attendants were women — young, attractive, and well-groomed. Uniforms by prominent designers — like TWA's French-inspired contemporary look by couturier Pierre Balmain — gave women like Diane Beers of New Jersey an enviably sophisticated air.

Competition for jobs was intense and expectations high. A stewardess was expected to handle with smooth professionalism the hospitality and safety needs of dozens of passengers. Her appearance was carefully regulated, including regular weigh-ins. Well into the 1960s, airline careers for women were usually short, ending with marriage or with women aging out in their early 30s.

Diane Beers joined TWA as an “air hostess” after earning an associate degree — major airlines often hired women with a college education. Here, Diane Beers poses proudly in her Pierre Balmain-designed TWA uniform, 1965. / THF718807 Gift of Diane B. Hill.

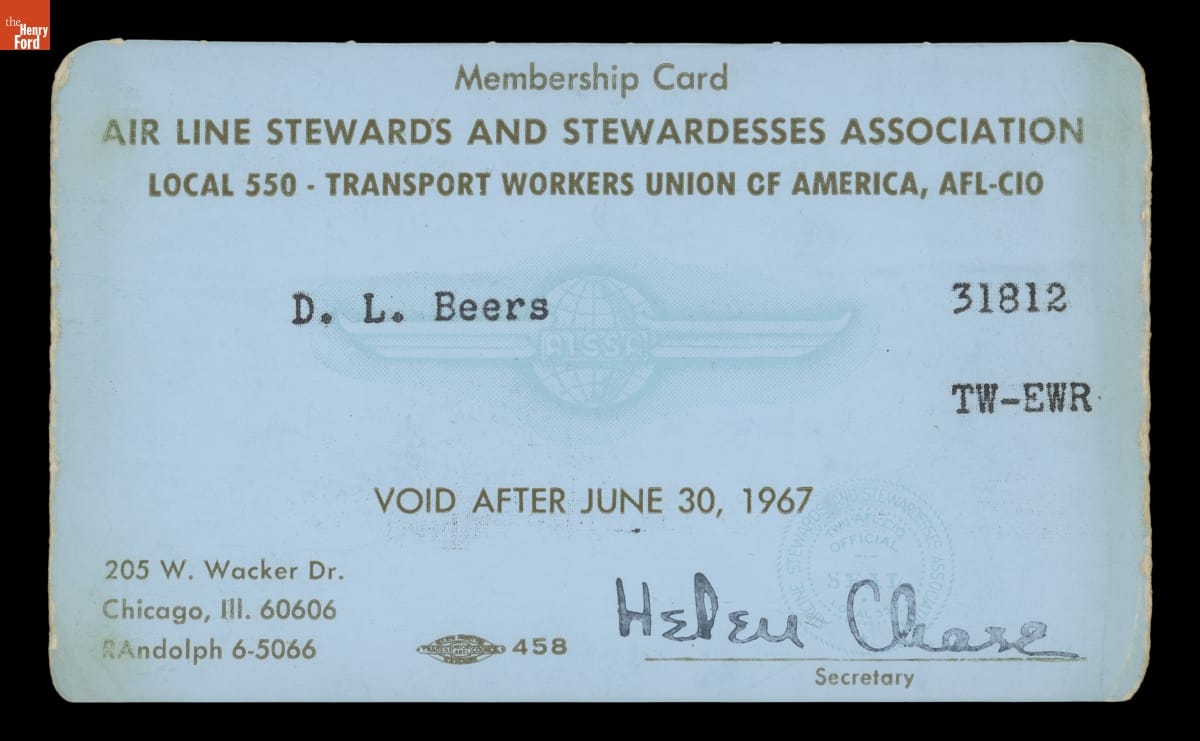

Air Line Stewards and Stewardesses Association membership card for Diane L. Beers, 1965. / THF718792 Gift of Diane B. Hill.

Flying was an event in the 1950s and 1960s. Stewardesses presented a polished appearance and professional demeanor as they served passengers. / THF717916

Dairy Delivery Worker

Twin Pines Dairy delivery uniform, about 1993. Worn by David Ivanko of Birmingham, Michigan. THF371986 Gift of John M. Ivanko.

There was a time when many households had a “milkman” who regularly delivered bottles of cold, fresh milk — in the 1950s, more than half of consumer milk sales came from these home delivery services. Customers conveniently placed standing orders but could change the order by leaving a note in one of the returned empty glass milk bottles. A dramatic increase in two-car families and small convenience stores changed things by the mid-1970s. Today, doorstep milk delivery is uncommon.

Twin Pines Dairy trucks were a familiar sight on the streets of the Detroit metro area in the 1950s and 1960s, covering approximately 500 delivery routes. During the time that John Ivanko of Birmingham, Michigan, owned a route in his wealthy Detroit area community, home delivery routes were far fewer — his was one of only about 50 in 1993.

Twin Pines milk bottle, about 1950. Twin Pines Farm Dairy was an employee-owned, independent cooperative, whose delivery routes were also independently owned and operated. / THF800558 Gift of Gail S. Woodruff.

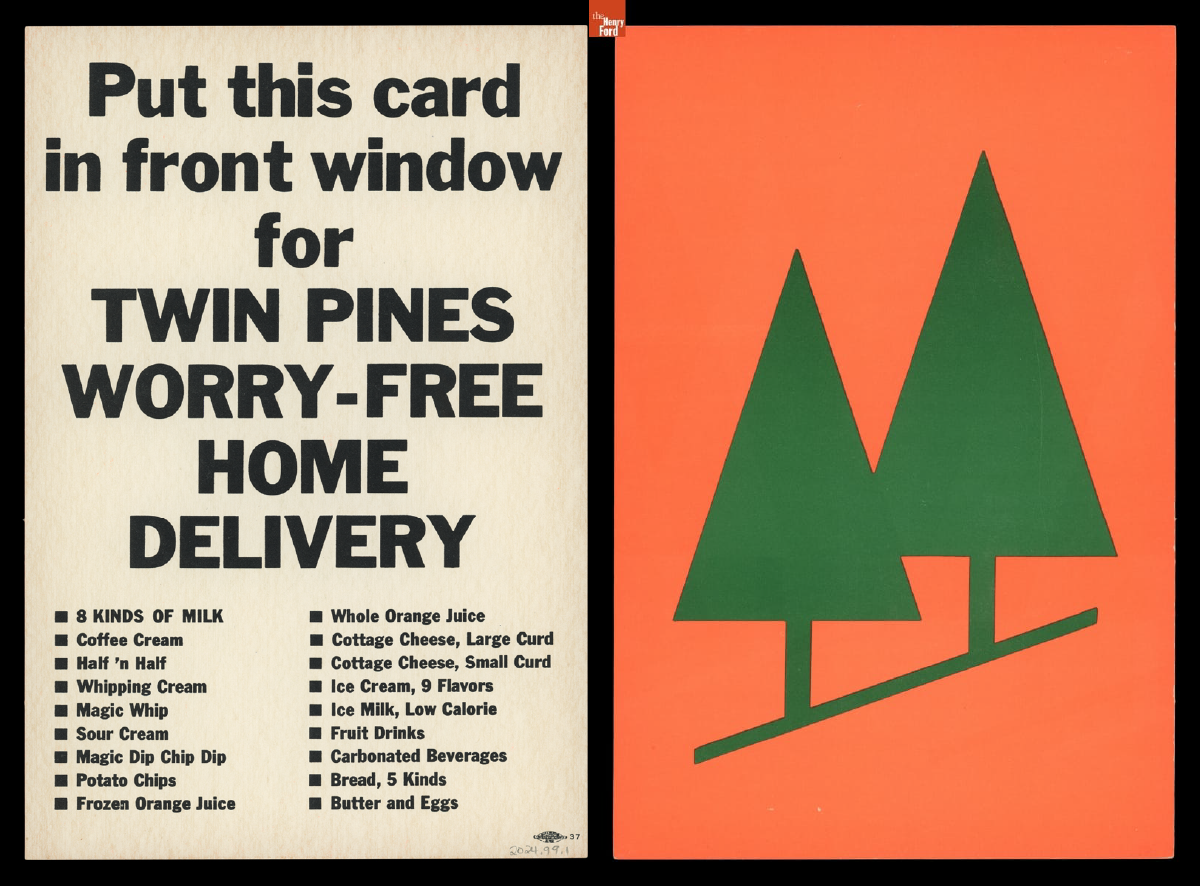

This Twin Pines window card lists the variety of products available for convenient, “worry-free” home delivery, 1965-1975. / THF718810, THF718809

Twin Pines Dairy drivers delivered their products to customers in trucks manufactured by the Divco Truck Company of Detroit, Michigan, shown in this late 1950s photo. / THF717898 Gift of Ralph Seabright.

Some homes had “milk chutes” built into a wall. Delivery workers opened the compartment from outside the house. Customers retrieved the milk through another door inside. Image courtesy of Kate Herron.

Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life.

What We Wore: Say Yes to the PROM Dress

The current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents a variety of prom dresses dating from 1960 to 2006 — and uncovers the stories they tell about this important rite of passage.

Proms are a much-anticipated milestone for many teenagers. High school students dress up in their most glamorous formal clothing to enjoy the much-anticipated event — an occasion guaranteed to create special memories.

For teen girls, especially, choosing the perfect dress is key to the experience! Weeks before the big event, what to wear becomes the hot topic of conversation at school and with friends. Traditionally, young women wear evening gowns — the hunt may involve a trip to local stores, searching online retailers, or even having a dress custom made. For young men, it’s simpler — they usually rent a tuxedo.

Continue ReadingMaria Grever: A Little Known — But Not Unsung — Composer

Images of the composer rarely appeared on sheet music for popular songs. Maria Grever’s photo graced the cover of “My Margarita” in 1939, along with photos of the performers, the usual images included to help increase sales of sheet music. / THF713047

What do the Andrews Sisters’ 1938 hit song “Ti-Pi-Tin” and Dinah Washington’s Grammy-winning 1959 recording of “What a Difference a Day Makes” have in common? Both songs were written by Maria Grever, the first female Mexican composer to attain international attention. Yet amazingly, Grever is little known today.

Grever, born Maria Joaquina de la Portilla in Mexico in 1885 to a Spanish father and Mexican mother, showed musical skills at an early age. While growing up in Spain and then Mexico, Grever’s wealthy family saw to it that she received a fine musical education, studying piano, violin and voice. Grever achieved early success as a composer; at 18, her song "A Una Ola" ('To a Wave') sold three million copies to its Latin audience.

When she was 22, Maria married Leon Grever, an American oil company executive working in Mexico. The couple had two surviving children. Amid the ongoing political turmoil of the Mexican Revolution, the Grever family arrived in New York City in June 1916. Leon returned to his job in Mexico while Maria remained in New York. For the next 35 years, Grever continued her musical career as a composer, singer and vocal coach in America as she navigated its New York-centered music industry.

In her compositions, Grever sought to share her Mexican heritage. While Grever was interested in modern jazz rhythms, above all she cherished Mexico’s rich musical culture. Latin music was only beginning to capture the attention of Americans in the 1930s. The rhumba, a genre of music and dance that combined American big-band music with Afro-Cuban rhythms, appeared in East Coast ballrooms. By the 1940s, Latin-influenced music — Grever’s compositions among them — had begun to take its place in popular songs, musicals and movie scores.

Maria Grever’s lush romantic songs and ballads focused on finding universal appeal as she mixed popular song forms with the rhythms of Latin American music. Grever wrote hundreds of songs — sources mention between 800 and 1,000 — composing the music and creating the Spanish lyrics. Her songs found popularity in Latin America and the United States. Grever also worked with American lyricists — including leading songwriters of the day Stanley Adams, Irving Caesar and Raymond Leveen — who translated her songs into English to increase their accessibility for American audiences. Grever wrote film scores for Paramount, MGM and 20th Century Fox. She created one-act operas, choral works and instrumental pieces in a wide variety of styles. Music critics noted her “innate gift of spontaneous melody.” Testimonials provided by performers mentioned her “exquisite melodies and rare rhythmical charm” and compositions that “are beautiful and reach the heart of the people.”

Maria Grever provided the Spanish lyrics for Cole Porter’s 1935 “Begin the Beguine.” / THF713039

In 1935, the year Grever became a member of ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), composer and lyricist Cole Porter, a fellow ASCAP member, asked Grever to provide Spanish lyrics for his musically complex “Begin the Beguine,” a song he wrote for the Broadway musical Jubilee.

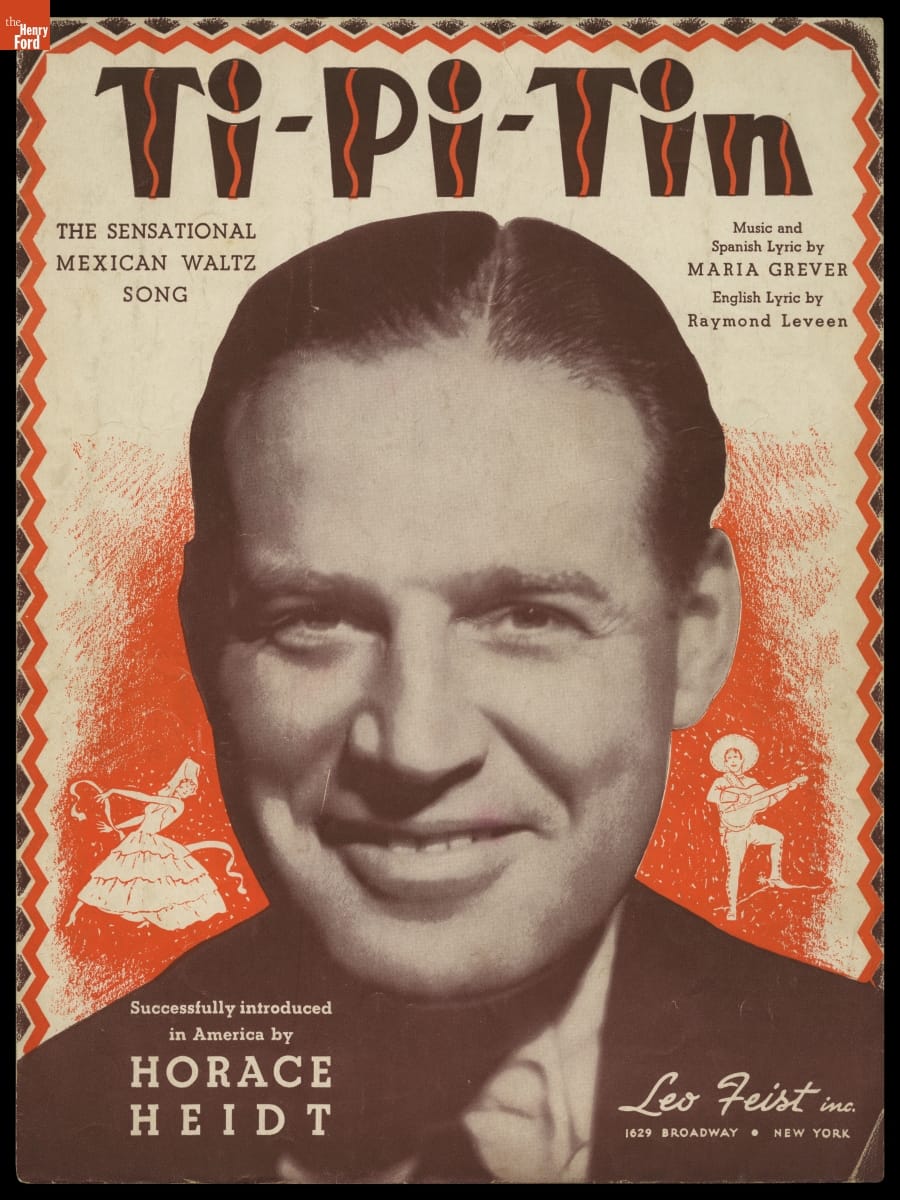

Maria Grever’s first big hit in America was “Ti-Pi-Tin.” / THF702012. Gift of Jeanine Head Miller.

Grever’s 1938 song “Ti-Pi-Tin" was Grever’s first big hit in the United States. Yet initially, Grever couldn’t interest a publisher in “Ti-Pi-Tin,” so she published it herself. When bandleader Horace Heidt heard the song, he quickly recognized its possibilities. His orchestra played it on NBC radio — immediately launching the song to success. The demand for sheet music was huge. To keep up, Grever allowed Leo Feist Inc. to publish it. That same year, the Andrews Sisters would create their own smooth and slightly jazzy version of “Ti-Pi-Tin.”

“Magic in the Moonlight,” a song Grever originally wrote in 1930 as “Te Quiero, Dijiste,” was featured in the 1944 MGM movie musical Bathing Beauty. / THF713033

Grever’s romantic ballad, “Magic Is the Moonlight” (Te Quiero, Dijiste) graced the 1944 MGM movie Bathing Beauty, a film that featured many on-screen performances by big-band greats of the era. In the movie, Carlos Ramírez sang Grever’s “Magic Is the Moonlight” in Spanish, accompanied by the Xavier Cugat Orchestra. The melody recurs throughout the film.

At the height of Grever’s career in the 1930s and 1940s, she was living at the Wellington Hotel at Seventh Avenue and 55th Street — near Broadway, Carnegie Hall and Central Park. The Wellington was a residential hotel that became a favorite among those in theatrical circles. The apartments of some tenants served as both living space and artistic studio. Here, in addition to composing music, Grever coached voice students on vocal technique and Spanish pronunciation.

Dinah Washington’s recording of Grever’s “What a Difference a Day Makes” ("Cuando Vuelva a Tu Lado") received a Grammy in 1959 for best R&B performance. / THF370537

Grever is best known for “What a Difference a Day Makes” ("Cuando Vuelva a Tu Lado"), written in 1934. Bing Crosby called it “the loveliest of all your lovely songs.” Dinah Washington’s 1959 recording, which earned her a Grammy for best R&B performance that year, made the song one of Grever’s longest-lasting hits.

While Maria Grever’s name is little known to most people today, her songs and international legacy live on. A host of singers — prominent and lesser-known — have performed Grever’s compositions, including Enrico Caruso, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, the Andrews Sisters, Tony Martin, Carlos Ramirez, Andrea Bocelli, Bobby Darin, Aretha Franklin, Gloria Estefan, Tony Bennett and Plácido Domingo. El Centre d’Estudis Musicals María Grever, a music school, can be found in Barcelona, Spain, while the theater Teatro María Grever is located in Grever’s birthplace of Leon, Mexico.

Though New York City was Maria Grever’s adopted home, upon her death in 1951 and at her request, Grever’s remains were transported to Mexico City to be buried in Panteon Español, just as she had wished.

As I wrote this blog, I relistened to some of Grever’s songs. Her tunes easily lingered in my mind — testimony to Maria’s Grever gift for melody.

Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford.

What We Wore: Reveal or Disguise?

The current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, on display until December 12, features costumes worn for Halloween and masquerade parties.

There is something compelling about wearing costumes — they can both reveal and disguise.

Costumes reflect our personality and interests. Show off our creativity. And let us take on another identity — transforming into someone or something else as we step out of our daily routines.

18th-century-style costume made by the Eaves Costume Company for Henry Ford, 1929. / THF154824, THF154830. Gift of the Clara Ford Estate.

18th-Century Style

In early 1929, Henry Ford asked a New York theatrical costume company to create this colonial-era costume for him. He said he wouldn’t need it until fall.

Ford was planning a celebration for October 21 of that year — one commemorating the 50th anniversary of Edison’s invention of the incandescent light. (The museum and village were formally dedicated that same day.) Did Ford intend to greet his guests at the evening banquet wearing 18th-century-style clothing? After all, they would be entering the museum through a replica of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall.

We’ll never know. Ford’s intentions remain a mystery — he hosted the event wearing contemporary formal dress. Whatever Ford’s plans had been, we do know that he felt the completed garments were too elaborate — even suggesting that some of the embroidery and bead trimmings be removed!

Henry Ford enjoyed wearing costumes from time to time. Dressed in 19th-century clothing, Henry, his wife, Clara, and their guests danced to the quadrilles, schottisches and polkas of Ford’s youth in the ballroom of the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts, in 1926. | THF148956. Gift of the Ford Motor Company.

Rabbit costume worn by a member of the Firestone family, 1956. | THF196404. Gift of Mrs. William Clay Ford, Mrs. John F. Ball and Mrs. William Leatherman.

Masquerading as Rabbits

When Harvey and Elizabeth Firestone purchased an oceanfront summer home in Newport, Rhode Island, in the early 1950s, they joined other wealthy, prominent people in Newport’s exclusive social scene. The White Elephant Ball, a masquerade party held at summer’s end, was one of Newport’s most sought-after soirees.

Elizabeth Firestone’s closet was filled with couture garments by prominent designers — her fashions were the talk of society. She was just as discerning — though more playful — when choosing costumes for the White Elephant Ball. In 1956, the Firestone family’s costumes reflected a whimsical fairyland theme — they came dressed as a family of humanlike rabbits.

Harvey and Elizabeth Firestone’s daughter Anne in her rabbit costume at the White Elephant Ball in 1956. | THF711467. Gift of Mrs. William Clay Ford, Mrs. John F. Ball and Mrs. William Leatherman.

Guests, dressed in masquerade costumes, gathered at venues like the Newport Country Club each year at summer’s end for the White Elephant Ball. | THF710383

Children's Costumes

Whether for dress-up play or to celebrate Halloween, homemade or store-bought, kids love donning costumes that reflect their personality or interests — letting them dream and use their imaginations.

Pirate costume made by Halco, 1940-1949. | THF196646

Pirate

Taking on the identity of a pirate is appealing — perhaps because pirates get to behave in ways that non-pirates don’t!

Drum Majorette costume, 1950-1955. | THF196359. Gift of Jeanine Head Miller.

Drum Majorette

Costume trends come and go. In the 1950s, drum majorette costumes were popular — kids could imagine themselves leading a marching band through the town!

Snow White costume, about 1960. | THF196315, THF196339. Gift of Mary Sherman.

Snow White

Since the 1930s, kids have enjoyed imagining themselves as a favorite character from Disney’s popular animated films.

Astronaut costume made by Ben Cooper Inc., 1966-1970. | THF196321, THF196343

Astronaut

Many kids dreamed of being an astronaut during the space race between the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1950s and 1960s — a race which effectively culminated in the July 1969 moon landing by American astronauts.

Blue Fairy costume worn by Lisa Korzetz of Southgate, Michigan, about 1966." title="THF196317">

Blue Fairy costume worn by Lisa Korzetz of Southgate, Michigan, about 1966." title="THF196317">

Blue Fairy costume mask worn by Lisa Korzetz of Southgate, Michigan, about 1966." title="THF196332">

Blue Fairy costume mask worn by Lisa Korzetz of Southgate, Michigan, about 1966." title="THF196332">

Blue Fairy costume worn by Lisa Korzetz of Southgate, Michigan, about 1966. THF196317, THF196332. Gift of Antoinette Nycek Korzetz.

Blue Fairy

The magical abilities of the Blue Fairy — a spirit who changed Pinocchio from a wooden marionette into a real boy — appealed to kids. Their parents appreciated the safety features of this costume, like flame-retardant fabric and bright colors for nighttime trick-or-treating.

Lisa Korzetz in her Blue Fairy costume with her brother Edward, about 1966. THF710392. Gift of Antoinette Nycek Korzetz.

Witch costume worn by Lisa Korzetz of Southgate, Michigan, 1971-1972. | THF196319, THF196350. Gift of Antoinette Nycek Korzetz.

Witch

Witch costumes are a classic Halloween choice, popular with both children and adults.

Barney-inspired costume worn by Eric Nietering of Dearborn, Michigan, 1993. | THF196354. Gift of Emily Nietering.

Barney

When the children’s television series Barney & Friends debuted in 1992, it became a runaway hit with preschool-age kids. Four-year-old Eric Nietering — like countless other children — was a big fan of Barney, a friendly, huggable T. Rex with an optimistic attitude.

Eric Nietering proudly poses in the Barney costume made by his mother, Emily. / THF710386. Gift of Emily Nietering.

Link costume worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021." title="THF196415">

Link costume worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021." title="THF196415">

Link costume shield worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021." title="THF196410">

Link costume shield worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021." title="THF196410">

Link costume sword worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021." title="THF196411">

Link costume sword worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021." title="THF196411">

Link costume worn by Isaac Morland of Canton, Michigan, 2021. | THF196415, THF196410, THF196411. Gift of Kate Morland.

Link

Kids love pretending to be characters from their favorite television shows, movies or video games. Isaac Morland chose a disguise as Link, a warrior hero from The Legend of Zelda video game.

Isaac Morland and his brother Simon dressed for Halloween in 2021. / THF710391. Gift of Kate Morland.

Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life.

Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle: Enduring Kitchen Icons from Corning

Three brands developed by Corning Glass Works during the 20th century — Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle — became household names that revolutionized American kitchens and endured decades of changing consumer tastes and expectations.

Corning Glass Works found both industrial and household applications for Pyrex. The company produced Pyrex insulators and laboratory glassware alongside its increasingly popular ovenware in the 1930s. Pyrex Perfect Antenna Insulator, 1930-1939. / THF174626

In 1908, scientists at Corning developed glass that could withstand extreme temperatures. It was initially used for industrial products like railroad lanterns and battery jars. Hoping to broaden the market, Corning spent years testing possible household applications. Encouraged partly by the success of one notable experiment — when Bessie Littleton, whose husband was a Corning researcher, used a modified glass battery jar to bake a cake — Corning introduced Pyrex, a line of temperature-resistant glass cookware. The launch of Pyrex in 1915 inaugurated a new Corning division dedicated to consumer products.

This early advertisement for Pyrex ovenware touts its many advantages. National Geographic, 1916. / THF709296

Pyrex bakeware entered the market at an advantageous time. In the early 20th century, the principles of scientific management — used in industrial settings to improve efficiency — found their way into the kitchen. Transparent Pyrex ovenware fit the bill — it performed well, was easy to clean and could go from oven to table. The Pyrex line was expensive at first — marketed initially to women of means interested in up-to-date products.

Pyrex Flameware Percolator, 1939-1951. / THF191912

Pyrex’s excellent performance in baking was unquestionable. Yet, to become a greater contender in the cookware industry, Pyrex would need to be usable for top-of-stove cooking on an open flame. The introduction of Pyrex Flameware in 1936 added this feature, increasing the product’s appeal. Too, changes in manufacturing helped make Pyrex more affordable by the 1930s.

Corning Ware Casserole Dish, 1960-1961. / THF192899

Next up? The accidental discovery of a new material — glass-ceramic — by a Corning research chemist in 1952. The gleaming white opaque material could withstand extreme cold and heat and didn’t break when dropped. First used in nose cones for radar-guided missiles, this new material found its way into the kitchen in 1958 as Corning Ware — a line of innovative, shatterproof cookware that could go right from the freezer to the oven or range and then to the table as a serving dish.

Corning advertisement, 1968. / THF710401

Versatile, durable, attractive and affordable, Pyrex and Corning Ware became staples in American kitchens.

Color and More

Pyrex Primary Colors Mixing Bowl Set, 1949-1957 and three Pyrex Primary Colors Refrigerator Dishes with Lids, 1947-1960. / THF167736, THF176489, THF176490 and THF176488

By the late 1940s, Corning sought to appeal to evolving post-World War II tastes with a focus on the center of the American home — the kitchen. Continuing the trend toward enlivening kitchens with new products in vibrant choices, Corning transformed Pyrex from colorless to colorful with the “Primary Colors” line, introduced in 1947. Customers could mix and match sets of cookware that were practical and functional but also stylish.

Cornflower Pattern Percolator, Teapot and Platter 1960-1961. / THF370218, THF370237, THF191905

Corning applied a similar styling approach to its revolutionary Corning Ware line. The popular Cornflower Blue pattern, introduced in 1958, became synonymous with Corning’s brand identity. It appeared on all sorts of products — most famously on casseroles but also on percolators, teapots and platters. Consumers could buy pieces as needed and eventually collect a color-coordinated set of cooking and serving ware. Later patterns reflected new trends and helped broaden the market for Corning Ware.

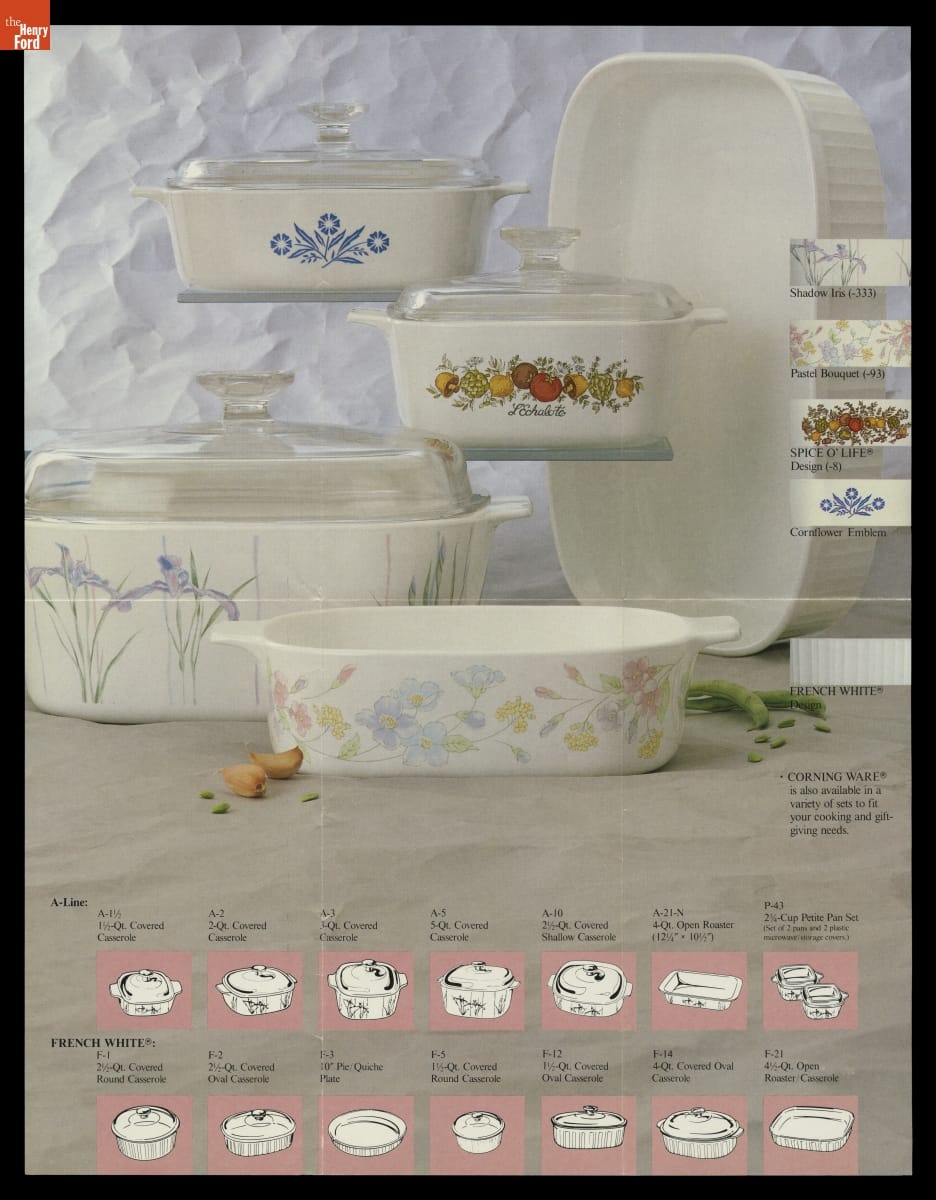

This Corning Ware brochure shows patterns available in 1987 — Shadow Iris, Pastel Bouquet, Spice O’ Life and the iconic Cornflower Emblem — as well as the now-classic French White line of casseroles. / THF709300

Revolutionizing the Dinner Table

Corelle Livingware cups and saucers in Butterfly Gold, 1971. / THF195008, THF195009, THF195011

Unlike Pyrex and Corning Ware — products made of new materials created without a singular purpose in mind — Corning deliberately pursued another kitchen innovation in the 1960s. The company thoroughly researched consumer preferences in dinnerware and then set to work on improving it. A breakthrough came in 1965 when a Corning scientist developed a laminating technique that produced very thin, yet very strong glass. Corning introduced Corelle Livingware, dinnerware made from this light and durable layered glass, in 1970.

Corelle Livingware dinnerware set in Spring Blossom Green, 1971. / THF195020

Corelle was a radical departure from the past, where expensive dinner sets consisted of many pieces, including luncheon plates and soup and salad bowls. By contrast, the first Corelle Livingware service consisted of a set of four large plates, four medium bowls, and four cups and saucers, retailing for the attractive price of $19.95. In addition, Corning provided a two-year guarantee to replace any piece that broke.

Corning’s savvy marketers compared Corelle to fine china. Product packaging with the slogan “looks, feels, and rings like china” depicted a mother “pinging” a Corelle plate. The company also offered consumers a selection of fashionable patterns. Pieces from the debut collection featured Butterfly Gold, Spring Blossom Green, Old Towne Blue and Snowflake Blue designs around the rim. Corning’s greens and golds were variations of the Harvest Gold and Avocado Green color schemes iconic of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Corelle was incredibly successful and changed middle-class American dining habits — it was chic yet durable and inexpensive enough for casual use. Corelle frequently sold out and was back-ordered throughout the 1970s. Corning continually added new “lifestyle” patterns and discontinued old ones to keep up with the latest decorative trends.

Still the Standard

Corning Pyrex FreshLock Plus food storage set with Microban antimicrobial product protection, 2022. / THF195359

Corning continually updated its Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle lines with new products that retained the qualities that had made them household names. The company sold its housewares division in 1998, but all three brands remained staples of American kitchens. In the 21st century, updated variations and marketing approaches appealed to changing tastes and lifestyle trends. Sets of Pyrex dishes designed for cold storage, portability and easy reheating featured locking plastic lids with odor-preventing technology. Marketers imagined new uses for classic Corning Ware, even designating some iconic French White casseroles as official companion pieces for the cult favorite Instant Pot brand of multicookers. (The company that manufactured Corning housewares merged with Instant Brands in 2019.) Continually updated Corelle patterns appealed to contemporary tastes.

Corelle Livingware dinnerware set in Northern Pines, 2022. / THF195362

Durable, convenient and stylish, the iconic brands developed by Corning in the 20th century continue to have relevance in today’s kitchens.

Charles Sable is curator of decorative arts, Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life and Saige Jedele is associate curator at The Henry Ford.

glass, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Charles Sable, 20th century

What We Wore: Shoes

From practical footwear to eye-catching fashion statements, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s current What We Wore exhibit is all about shoes. On display are 30 pairs of men’s, women’s and children’s shoes dating from the 1780s to the 2000s.

Each pair offers a bit of footwear history — and, for some perhaps, a familiar style once found in their own closet!

Shoes will be on display until May 24. Here’s a peek at a few examples.

Men’s Boudoir Slippers, 1855-1860 / THF31115

Men's embroidered slippers were very popular in the mid-1800s. Ladies magazines often included embroidery patterns for house slippers that a woman might make for her husband as a gift.

Men’s Wingtip Oxfords, 1945-1955, Gift of Richard Glenn / THF370088

The low-sided oxford came into fashion for men’s footwear in the 1910s, along with wingtips (a toe cap in the shape of a bird’s wing embellished with a perforated pattern). White shoes were for summer.

Reebok Pump AXT Cross-Training Shoes, circa 1990 / THF370066

In the 1970s, athletic shoes became big business as the popularity of running and more relaxed dress codes in workplaces and schools led to a boom in the market. Manufacturers developed high-tech features designed for more support and stability. Reebok introduced the Reebok Pump in 1990, a shoe that used inflatable chambers that pumped-up for a custom fit.

Women’s Shoes, 1785-1789, Gift of American Textile History Museum / THF370062

Before shoemaking became a mechanized industry in the mid-1800s, shoes were made by hand. Amos Boardman created these silk shoes — undoubtedly for a prosperous client— in one of the many small shoemaking home-shops that flourished in late 1700s New England.

Women's Boots, 1867, Gift of Cora D. Maggini, Worn by Angeline (Anna) Duckworth when she married Rufus Larkin in Posey County, Indiana, in September 1867 / THF158262

Sandals from ancient Greece or Rome inspired these 1860s shoes — footwear designed to reveal pretty-colored silk stockings beneath!

Women’s Platform Shoes, 1945-1950, Gift of American Textile History Museum, Donated to ATHM by Sharon and Phil Ferraguto / THF370078

Introduced in the late 1930s, platform shoes remained popular through the 1940s. These eye-catching examples sport cherry red, ivory and gray reptile leather.

Women’s Glitter Jelly Sandals, circa 1990 / THF172055

Jelly shoes were a favorite among young women in the 1980s and 1990s. Made of PVC plastic, the shoes came in a rainbow of colors. Sandals were the most popular.

Girls’ Slippers, circa 1850 / THF156007

In the mid-1800s, girls wore slippers with ribbon ties for formal occasions. For everyday? Low boots.

Boys’ Boots, circa 1865 / THF156008

Children’s clothing has increasingly included images that have appeal for a child. These are an early example — Civil War-era boots with a figure of a dashing Zouave soldier.

Saddle Oxfords, 1955-1965, Gift of Randolph C. and Nancy M. Carey / THF78930

The saddle shoe, with its contrasting color leather “saddle,” is a style icon. Worn by uniformed schoolkids since the 1930s and by “bobby soxer” teens in the 1940s and 1950s, the saddle shoe has an enduring link to youth culture.

Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford.

What We Wore, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, by Jeanine Head Miller, 20th century

Bonnie Cashin: Innovative and Influential

Our latest installation of What We Wore: Bonnie Cashin. / THF191461

The current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation features clothing by Bonnie Cashin. American designer Bonnie Cashin’s ideas, radical when introduced, have become timeless.

Who was Bonnie Cashin? An inscription in her senior yearbook provided a hint of things to come: “To a kid with spark—may you set the world on fire.” She did. By the 1950s, Cashin had become “a mother of American sportswear” and one of the most influential fashion designers of the 20th century.

Born in 1908 in California, Bonnie Cashin apprenticed in her mother’s custom dress shop. At 16, she began designing chorus costumes for a Hollywood theater. Next stop—the Roxy Theatre in New York City, where the 25-year-old was the sole designer. The street clothes Cashin designed for a fashion-themed revue led to a job at the prestigious ready-to-wear firm Adler & Adler in 1937. Cashin left for California in 1943, where she spent six years at 20th Century Fox, designing costumes for approximately 60 films.

Cashin’s designs for the 1944 movie Laura were the most influential of her 20th Century Fox creations. Motion pictures of the 1940s tended to showcase female stars as wealthy and glamorous women. Cashin’s designs for actress Gene Tierney suggested clothing chosen by the character of Laura herself, rather than costumes worn for an actress’s role. A revolutionary concept for the time, the garments reflected Cashin's real-life views. / THF700871

Cashin and actress Olivia de Haviland look over costumes created for the motion picture The Snake Pit in 1948. / THF703254

In 1949, back in New York, Cashin created her first ready-to-wear collection under her own name. Cashin designed for “the woman who is always on the go, who is doing something.” She introduced the concept of layering, with each piece designed to work in an ensemble, alone, and in different combinations. The fashion world took notice. In 1950, Cashin won both the prestigious Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award and the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award.

This 1952 ad dates from the year Bonnie Cashin opened her own design studio. It captures the spirit of Cashin’s intended customers—women always on the go. / THF701655

In 1952, Cashin opened her own one-woman firm, Bonnie Cashin Designs. Cashin insisted on total creative control as she worked with the manufacturers who produced her designs. Cashin chose craftsmanship over commercial success. She never wavered in her artistic vision—functional simplicity and elegant solutions.

Jacket (Wool, Brown Leather Binding, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1970, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188918

Trousers (Suede), 1955–1960, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188947

Many Cashin designs were practical solutions to problems she herself experienced. Her tailored poncho was born after she cut a hole in a blanket to cope with temperature fluctuations while driving her convertible through the Hollywood Hills.

Coat (Mohair, Suede Bindings, Brass Clip Closure), 1955–1964, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188928

Sweater (Cashmere, Brass Buttons), 1955–1964, Designed by Bonnie Cashin, New York City, and Made by Ballantyne, Innerleithen and Peebles, Scotland. / THF188908

Trousers (Leather, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1970, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188945

Cashin is most well-known for her innovative use of leather, mohair, suede, knits, and nubby fabric, as well as heavy hardware used as fastenings. Cashin had a deep love of color and texture—she personally selected, designed, or commissioned her fabrics.

In this 1972 ad for Singer sewing machines, examples of Bonnie Cashin’s favored textiles—suede, leather, knits, and nubby tweeds—appear on the shelves behind her. / THF700873

Traveling widely during her career, Cashin closely studied the traditional clothing of other cultures. Her international focus and attention to refining traditional shapes down to their most modern and mobile forms led to her distinctive “Cashin Look.”

Jacket (Mohair Bouclé, Leather Bindings, Brass Sweater Guard Closure), about 1965, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City; Fabric Made by Bernat Klein, Galashiels, Scotland. / THF188913

Bonnie Cashin created dazzling costumes for the stage and screen—then excelled at exquisite minimalism in her sportwear. The intersection? Cashin’s garments always moved with the wearer and were designed to be set against a backdrop—whether a theatrical scene or contemporary life.

Coat (Wool, Leather Binding), 1965–1972, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188933

Trousers (Leather, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1972, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188943

Jacket (Leather, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1972, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188938

Innovative and influential, Cashin continued to design until 1985. Following her death in 2000, among the handwritten notes jotted on scraps of paper in her apartment was one that read, “How nice for one voice to ignite the imaginations of others.”

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, California, New York, women's history, What We Wore, movies, making, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, entrepreneurship, design, by Jeanine Head Miller

Hallmark Keepsake Ornaments: Curator Q&A

We are quickly drawing closer to the November 20 opening of our newest permanent exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation: Miniature Moments: A Journey Through Hallmark® Keepsake Ornaments. With just a few weeks to go, we checked in with Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life, and Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life, to collect their thoughts on our collection of nearly 7,000 Hallmark Keepsake Ornaments. Check out their answers below.

What is the oldest Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

One of Hallmark’s first ornaments from 1973, designed by artist Betsey Clark. / THF178137

Jeanine Head Miller (JHM): The ornaments in this collection date back to the first year that Hallmark produced Christmas ornaments—1973. That year, the company offered six decorated ball ornaments and twelve yarn ornaments. While the shape of Hallmark’s ball ornaments was traditional, the artwork, printed on a plastic sleeve and then heat-shrunk to the ornament, was an innovation. Hallmark’s simple yarn figures evoked nostalgic visions of Christmases long ago—the years leading up to America’s American Revolution Bicentennial celebration saw an increased interest in “early American” traditions.

Hallmark’s 1973 yarn ornament series included this colorful toy soldier. / THF177677

What is the newest Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

JHM: The newest ornaments are the 269 made in 2009. (Yes—the number of ornaments released by Hallmark each year has grown!) These later ornaments reflect the increasing complexity of Hallmark’s designs. The vast majority of the company’s ornaments by this time were figurals (shapes that represent objects), with many being highly detailed. Ornaments sporting traditional Christmas themes were joined by an ever-evolving array of popular culture and technology-themed decorations. Customers appreciated the way that Hallmark’s designs helped them “personalize” their tree—a growing trend in Christmas tree decorating—using ornaments that reflected their own interests and experiences.

Hallmark’s 2009 "Ralphie's Pink Nightmare" ornament from the movie A Christmas Story depicts an unhappy Ralphie dressed in Aunt Clara’s pink bunny suit gift. / THF177263

Hallmark’s 2009 "Wired for Fun" teenage reindeer multitasks as he entertains himself with up-to-date digital technology—an MP3 player and a wireless video game. / THF358063

For the passionate culinary wizard, Hallmark’s 2009 "Snow Much Fun to Cook" ornament. / THF357697

What is the most common Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

Donna R. Braden (DRB): This is a bit of a difficult question to answer. There is no easily available information on ornaments that were either produced or purchased in the greatest quantities, or those that are the easiest to find today. However, we might assume that those might align with the categories of ornaments that tend to be produced in the greatest number and variety. This varies over the years, but today—according to the 2022 Dream Book (and probably characteristic of the more recent years of our collection)—they are ornaments with classic Christmas themes, series favorites, Disney ornaments, meaningful moments and milestones, and popular culture characters, including Star Wars, Star Trek, superheroes, Harry Potter, toys, Peanuts, and Barbie.

What is the rarest Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

DRB: Again, this is difficult to pin down. Lots of eBay listings for Hallmark Keepsake Ornaments say “extremely rare,” but these don’t necessarily cost a lot of money. Rarity can be based on the look, the artist, the date, the number in the series (especially firsts), and the popularity of the topic. Five rare ornaments I’ve seen listed follow below. The 1973 Betsey Clark ornament Jeanie notes as one of the earliest in our collection also seems to be rare.

"Mary's Angels Series: Buttercup,” 1988, is the first in its series. / THF182250

“Santa's Motorcar,” 1979, is the first in the Here Comes Santa series. / THF176990

"Tin Locomotive,” from 1982, is also rare. / THF177179

Another rare listing is “Miss Piggy” from 1983. / THF177327

"Starship Enterprise" is rare, even though it’s less than 40 years old. / THF177369

What is the largest Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

JHM: Over the years, many Hallmark ornaments have grown in size—some five inches high or more—and complexity, adding narrative embellishment through visual detail, light, motion, and sound effects. Some—designed to be displayed on a flat surface—are more like figurines.

This large 2006 “Letters to Santa” ornament—about 5 ½ inches high and made to be hung on the tree—not only brims with charming detail, it offers motion and sound features. Pulling the bell below this battery-powered ornament causes several toys around Santa’s desk spring to life, as eight humorous recordings of children reading their letters to Santa are heard. / THF362217

This 1994 “Beatles Gift Set,” four inches high, commemorates the 30th anniversary of the Beatles’ 1964 appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show—one of the first times Hallmark Keepsake Ornaments had attempted likenesses of real people. / THF352350

The 2002 scene “The Family Room”—five inches high—was a group effort, with details of this homey design contributed by 19 Hallmark artists. / THF362466

What is the most valuable Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

DRB: This is difficult to pin down, as it varies by changing collectability over the years—and The Henry Ford doesn’t collect based on monetary value, but instead on historical significance. However, the one ornament that shows up over and over is a 2009 ornament representing Cousin Eddie’s RV from the movie National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation.

Hallmark "National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation: Cousin Eddie's RV" Christmas Ornament, 2009. / THF361864

What is your favorite Hallmark Keepsake Ornament in The Henry Ford’s collection?

JHM: Hmmm… while I admit being partial to Hallmark’s small buildings, my favorite ornament—if I had to choose just one—is "Christmas Cookies!" from 2004. Why do I love it? This tiny stove with its charming cooking-making details immediately immerses me into happy childhood memories of baking Christmas cookies with my mother and sisters. A few years ago, my husband located one of these nearly 20-year-old ornaments online and gave it to me as a Christmas gift.

Hallmark’s "Christmas Cookies!" ornament, 2004. The lights inside the oven glow, and a fragrance insert emits the sweet scent of cookies “baking.” / THF177744

DRB: “Baby’s First Christmas,” from 1990, is my favorite ornament for personal reasons. My daughter Caroline was born that year. We were not big Hallmark ornament purchasers yet (that mushroomed later), but we saw this and it really “spoke” to us as a perfect symbol of this important milestone in our lives. We imagined being able to relive the memories of that milestone every year. And we do! More than 30 years later, it still occupies a prominent place on our Christmas tree every year.

Baby’s First Christmas, 1990. / THF177026

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford, Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford, and Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Miniature Moments: A Journey Through Hallmark® Keepsake Ornaments

- Hallmark "Our Family Photo Holder" Christmas Ornament, 2006

- Through the Years with Hallmark Ornaments

- Digitizing Our Collection of Hallmark Keepsake Ornaments: A Collection Management Perspective

2000s, 21st century, 1990s, 1980s, 1970s, 20th century, popular culture, Miniature Moments, home life, holidays, Henry Ford Museum, Hallmark, Christmas, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Ellice Engdahl, by Donna R. Braden