Posts Tagged gardening

My friend Jennifer introduced me to Marian Morash’s The Victory Garden Cookbook (Alfred A. Knopf, 1982) in 2022. She explained that the cookbook was her mother's go-to wedding present. When Jennifer and her daughter saw a feature article about Mrs. Morash and her husband in Better Homes & Gardens (2017) they wrote her. They thanked her for the inspiration the cookbook provided three generations of cooks in Jennifer's family, and the modest Beard-Award-winning chef, author and TV personality wrote back, amazed that the cookbook could still be found.

Marian’s inspiration came from none other than Julia Child who passed along partially cooked foods from a cooking show that Marian’s husband, Russell Morash, piloted in 1962. The following summarizes the connections that laid the groundwork for the influential Victory Garden Cookbook.

Dust jacket, The Victory Garden Cookbook (1982). / THF708642

Hardcover, The Victory Garden Cookbook (1982). / THF708645

Morash's Background and Inspiration

Morash’s husband, TV producer Russell Morash, first encountered Julia Child, co-author of Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1962), on the WGBH-TV show I’ve Been Reading, in an episode likely broadcast on February 19, 1962. Child captivated WGBH-TV staff and viewers with her cooking demonstration, and the station decided to produce three pilot episodes of The French Chef. These aired in 1962 on July 26 (the omelet), August 2 (coq au vin) and August 23 (the souffle). The new series, The French Chef, debuted February 11, 1963. Marian’s husband, Russell Morash, produced the new series. The half-prepared recipes that Russell salvaged from the show, along with Julia Child’s directions written to Marian so she could complete the cooking, nurtured the nascent chef. In 1975, Marian co-founded Straight Wharf Restaurant in Nantucket, Massachusetts, and ran it as executive chef. Continue Reading

Ford Novelty Band Playing at Ford Baseball Team Game, 1941 / THF271722

Every month, we feature some items from our archives in our History Outside the Box program. You can check the new story out on The Henry Ford’s Instagram account on the first Friday of the month, but we’re reposting some of the stories here on our blog as well. In May 2021, Reference Archivist Kathy Makas shared photographs, articles, and other documents ranging from the 1910s through the 1950s that detail how employees at Ford Motor Company spent their leisure time. Learn more about Ford’s musical groups, sports teams, gardeners, and social/service clubs in the video below.

Continue Reading

Dearborn, Michigan, 20th century, sports, music, History Outside the Box, gardening, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, by Kathy Makas, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

How Does Your Vegetable Garden Grow?

Do you raise vegetables to feed yourself? If the answer is “Yes,” you are not alone. The National Gardening Survey reported that 77 percent of American households gardened in 2018, and the number of young gardeners (ages 18 to 34) increased exponentially from previous years. Why? Concern about food sources, an interest in healthy eating, and a DIY approach to problem solving motivate most to take up the trowel.

The process of raising vegetables to feed yourself carries with it a sense of urgency that many of us with kitchen cabinets full of canned goods cannot fathom. Farm families planted, cultivated, harvested, processed and consumed their own garden produce into the 20th century. This was hard but required work to satisfy their needs.

Two members of the Lancaster Unit of the Woman’s National Farm and Garden Association digging potatoes, 1918. THF 288960

Seed Sources

Gardeners need seeds. Before the mid-19th century, home gardeners saved their own seeds for the next year’s crop. If a disaster destroyed the next year’s seeds, home gardeners had to purchase seeds.

Commercial seed sales began as early as 1790 in the community of Shakers at Watervliet, New York. The Mt. Lebanon, New York, Shaker community established the Shaker Seed Company in 1794. The Watervliet Shakers first sold pre-packaged seeds in 1835, but the Mt. Lebanon community dominated the garden seed business until 1891. They marketed prepackaged seeds in boxes like this directly to store owners who sold to customers.

Shakers Genuine Garden Seeds Box, 1861-1895. THF 173513

Satisfying the demand for garden seeds became big business. Entrepreneurs established seed farms and warehouses in cities where laborers cultivated, cleaned, stored and packaged seeds. The D.M. Ferry & Co. provides a good example.

D.M. Ferry & Company Headquarters and Warehouse, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1880. THF76854

Entrepreneurs invested earnings into this lucrative industry.

Hiram Sibley, who made a fortune in telegraphy, and spent 16 years as president of the Western Union Telegraph Company, claimed to have the largest seed farm in the world, and an international production and distribution system based in Rochester, New York, and Chicago, Illinois. Though the company name changed, the techniques of prepackaging seeds developed by the Shakers at Watervliet and direct marketing of filled boxes to store owners remained an industry standard.

Hiram Sibley & Co. Seed Box, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181542

Planting gardens requires prepackaged seeds (unless you save your own!). These little packets tell big stories about ingenuity and resourcefulness. We acquired this 1880s Sibley & Co. seed box from the Barnes Store in Rock Stream, NY in 1929.

The original Sibley seed papers and packets are on view in a replica Hiram Sibley & Co seed box in the J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, which our members and guests will be able to enjoy once again when we reopen. Until then, take a virtual trip to the store by way of Mo Rocca and Innovation Nation.

Looking for gardening inspiration? Historic seed and flower packets can provide plenty! Survey the hundreds of seed packets dated 1880s to the present in our digital collections and create your own virtual garden.

The variety might astound you, from the mangelwurzel (raised for livestock feed) to the Early Acme Tomato and the Giant Rocca Onion.

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Beet Long Red Mangelwurtzel” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181520

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Tomato Early Acme” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF278980

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Onion Giant Rocca” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF279020

Families in cities often did not have land to cultivate, so they relied on the public markets and green grocers as the source of their vegetables.

Canned goods changed the relationships between gardeners and their responsibility for meeting their own food needs. Affordable and available canned goods made it easy for most to hang up their garden trowels. As a result, raising vegetables became a lifestyle choice rather than a necessity for most Americans by the 1930s.

Can Label, “Butterfly Brand Stringless Beans,” circa 1880. THF293949

Times of crisis increase both personal interest and public investment in home-grown vegetables, as the national Victory Garden movements of the 20th century confirm.

Victory Gardens

Man Inspecting Tomato Plant in Victory Garden, June 1944. THF273191

Victory Gardens, a patriotic act during World War I and World War II, provide important examples of food resourcefulness and ingenuity.

You can find your own inspiration from Victory Garden items in our collections – from 1918 posters to Ford Motor Company gardens during the 1930s, and home-front mobilization during World War II here.

Woman's National Farm and Garden Association at Dedham Square Truck Market, 1918. THF288964

But the “fruits” of the garden didn’t just stay at home. Entrepreneurial-minded Americans took their goods to market, like these members of the Woman's National Farm & Garden Association and their "pop-up" curbside market in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1918.

Clara Ford with a Model of the Roadside Market She Designed, circa 1930. THF117982

Clara Ford, at one time a president of the Women’s National Farm and Garden Association, also believed in the importance of eating local. Read more about her involvement with roadside markets here.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

food, agriculture, gardening, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid

Celebrating Earth Day

As we celebrate Earth Day, do you know which iconic symbol for the environmentalism movement came first? The bird wing design on an Earth Day poster or the “Give Earth a Chance” button? If you thought it was the button, you’re correct.

Give Earth a Chance Button, 1970. THF284833

Students at the University of Michigan formed ENACT (Environmental Action for Survival Committee, Inc.) in 1969. They prototyped the button and started selling it in late 1969, months before the official Earth Day on April 22, 1970. This button was reputedly worn during Earth Day 1970.

Advertising Poster, "Earth Day April 22, 1970.” THF81862

If you picked the wing, the artist that created the poster, Jacob Landau, used a stylized wing in earlier artwork. Landau, an award-winning illustrator and artist, taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He created this poster for the Environmental Action Coalition which coordinated New York Earth Day activities in 1970.

Did Earth Day launch the Age of Conservation?

“Newsweek” Magazine. THF139548_redacted

Newsweek itemized threats that ravaged the environment in its January 26, 1970 issue. All resulted from human actions. Emissions and sewage polluted the air and water. Garbage clogged landfills. Population growth threatened to overtake available food supplies. Solving these challenges required cooperation and unity on the part of individuals as well as local, state, and national governments. Editors believed that replenishing the environment to sustain future generations could be “the greatest test” humans faced. They featured the “Give Earth a Chance” button with the caption: "Symbol of The Age of Conservation?"

What to do to save the Earth?

The overall goal of replenishing the environment to sustain future generations required action on many fronts. More than 20 million people across the United States participated in the first Earth Day. The teach-ins informed, marches conveyed the intensity of public interest, and graphic arts spoke volumes about what needed to be done.

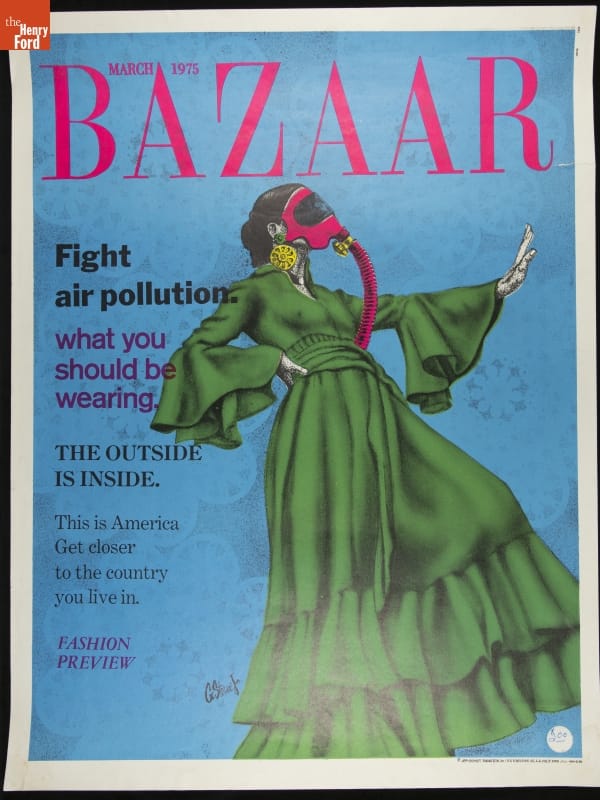

“March 1975, Bazaar, Fight Air Pollution, What You Should Be Wearing,” Poster, 1970. THF288328

This 1970 poster envisioned high fashion of the future, complete with a gas mask accessory. The moral of the story? Self-protection would not solve the problem of environmental pollution.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 empowered states and the national government to reduce emissions through regulation. This applied to industrial emissions as well as mobile sources (trains, planes, and automobiles, among others).

Interest in Recycling Grows

Poster by Eli Leon for Ecology Action, “Recycle” 1971. THF284835

Recycling emerged as a natural outgrowth of Earth Day, but local efforts could not succeed without explanation. First, consumers had to be convinced to save their newspapers, bottles, and cans, and then to make the extra effort to drop them off at centralized locations. This flyer showed how every-day consumer activity (grocery shopping) contributed to deforestation, littering, and garbage pile-up. Everybody could participate in the solution – recycling.

Recycling cost money, and this caused communities to balance what was good for the Earth, acceptable to residents, and possible within available operating funds. Even if customers voluntarily recycled, it still cost money to store recyclables and to sell the post-consumer materials to buyers.

Recycling Bin, Designed for Use in University City, Missouri, 1973. THF181540

City officials and residents in University City, Missouri, started curbside newspaper recycling in 1973, one of the first in the country to do so. Some argued that the city lost money because the investment in staff and trucks to haul materials cost more than the city earned from the sale, but saving the planet, not profit, motivated the effort. Eight years into the program, in 1981, city officials estimated that newspaper recycling kept 85,000 trees from the paper mill.

Easter Greeting Card, "Happy Easter," 1989-1990. THF114178

Today, more than 1/3 of post-consumer waste, by weight, is paper. Processing requires energy & chemicals, but recycled paper uses less water and produces less air pollution than making new paper from wood pulp. Maybe you buy greeting cards of 100% recycled paper, like this late 1980s example from our digital collections.

Environmentalism and Vegetable Gardening

Awareness of environmental issues affected the habits and actions of gardeners. Home gardening became an act of self-preservation in the context of Earth Day and environmentalism.

Lyman P. Wood founded Gardens for All in 1971, and the association conducted its first Gallup poll of a representative sample of American gardeners in 1973. It helped document the actions of gardeners, those proactive subscribers to new serials such as Mother Earth News. It confirmed their demographics and their economic investment.

Mother Earth News, 1970. THF290238

Raising vegetables using organic or natural fertilizers and traditional pest control methods became an act of resistance to increased use of synthetic chemical applications as concern about residual effects on human health increased.

How to Grow Vegetables and Fruits by the Organic Method, 1971. THF145272

Interest in organic methods remains high as concern about genetic-engineered foods polarizes consumers. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines biotechnology broadly. The definition includes plants that result from selective breeding and hybridization, as practiced by Luther Burbank, among others, as well as genetic modification accomplished by inserting foreign DNA/RNA into plant cells. This last became commercially viable only after 1987. These definitions affect seed marketing, as this “organic” Burbank Tomato (not genetically engineered) indicates.

Charles C. Hart Seed Company “Burbank Slicing Tomato” Seed Packet, circa 2018. THF276144

What Gardening Means Today

Gardening as an act of personal autonomy

"Assuming Financial Risk," Clip from Interview with Melvin Parson, April 5, 2019. THF295329

Social justice entrepreneurs believe gardens and gardening can change lives. Learn about the work of Melvin Parson, the Spring 2019 William Davidson Foundation Entrepreneur in Residence at The Henry Ford, in this expert set. You can also learn more from Will Allen in an interview in our Visionaries on Innovation series.

Environmentalism

The 1970 “The Age of Conservation” has changed with the times, but individual acts and world-wide efforts still sustain efforts to “Give the Earth a Chance.” You can learn more about environmentalism over the decades by viewing artifacts here.

To read more about Adam Rome and The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (2013), take a look at this site.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. This post came from a Twitter chat hosted in celebration of Earth Day 2020.

20th century, 1970s, nature, gardening, environmentalism, by Debra A. Reid, #THFCuratorChat

Guide to the Gardens at Greenfield Village's Historic Homes

Spring has finally arrived at Greenfield Village!

While this gives us many causes for celebration – including the Village’s re-opening – one of my favorite elements of the season is watching the gardens in our historic homes grow.

We have a wide variety of crops that grow in many different styles of gardens throughout Greenfield Village – and of course, all are cultivated according to that particular home’s geographic location and time period.

Let’s take a walk through the gardens!

Daggett Garden (built in 1754 in Andover, Connecticut)

At Daggett, we show a very traditional way to garden. The word garden means “to guard in”--just as you guard something in with a fence, you guarded in your crops. In crowded European cities, where the American colonists came from, you’d see them growing their crops in tiers and boxed beds because the cities were crowded and you had to maximize the amount of crops you got from each square foot of gardening.

This is another location with raised beds, which were just rebuilt last year; we grow a variety of vegetables, herbs, flowers and even concord grapes – and just look at how big the cabbages we grow can get!

Susquehanna Plantation (built circa 1835 in St. Mary’s County, Maryland)

At this home’s original location, tobacco was the crop that the enslaved African Americans would have tended and grown. Growing tobacco was back-breaking work. Henry and Elizabeth Carroll enjoyed a very prosperous life from selling this tobacco; in 1860 alone, Carroll sold over 10,000 tons of the crop. Today, you can still see the same variety of tobacco grown in the fields surrounding the plantation, although it doesn’t grow quite as well here in the North.

We start the plants early in what’s called a cold frame because the growing season for tobacco is quite long – more than 140 days. In the 19th century, tobacco plants were started in protected seed beds, and then transplanted into hills in the fields. It was not uncommon to plant lettuce along with the tobacco seeds in the seed beds to act as a buffer, and to draw leaf-mulching insects away. Notice how the tobacco is being grown here, in a mound almost three feet high; to do this, you stick your foot in the mound, hoe up the soil up to your knee, pull out your foot, and then put the plant into the ground with your whole fist. From there, you have to keep mounding up and up.

When the time is right, the entire top of the plant is pinched off to prevent it from going to seed and ending its growing cycle too soon. This will cause the plant to try and replace its top with a lot of small shoots called suckers, so this is when the process of “suckering” begins: taking off the smaller leaves so that only a few leaves (about 12-14) will get really big instead.

With open pollinated heirloom varieties, such as we use, you always save the seed and grow your crops again next year – this way, you maintain an original variety of the plant, and as a bonus, you don’t have to buy new seeds each year!

Mattox Garden (built about 1880 in Bryan County, Georgia)

Here, we grow okra – specifically, Georgia Jade okra, an heirloom variety that actually grows very well here in Michigan. You’d be surprised by the abundance of okra you can get, even in such a contrasting growing location.

To do this, we work a good mulch right into the beds, which helps the water stays within the bed itself; it doesn’t run off and evaporate as much as it does when you have row crops.

We also grow everything from yellow bantam corn, radishes, Muscadine and Scuppernong grapes, tomatoes and collard, mustard and turnip greens. With corn, tomatoes and okra, you can mix that with a rice dish, throw in a ham hock – and you have yourself all different kinds of gumbos and jambalayas. That was very typical Southern cuisine.

(For another example of a classic Southern dish, watch our video here on how to make Hoppin’ John, from our cooking demonstrations during Celebrate Black History! in Henry Ford Museum.)

Firestone Farm (built in 1828 in Columbiana, Ohio)

Although the Firestone home was built in 1828, we show life as it was lived at this farm in the 1880s – and that means vegetables planted in neat rows in the kitchen garden.

Most of our crops are directly sown and include a number of different pole and bush bean varieties. Dry beans were an important part of the winter stores as they would keep and could be used in a number of ways.

We also have quite an assortment of fruit trees at Firestone Farm, with the most important being the apples that grow both in our small orchard and in the back yard of the farmhouse. Some types of apples kept all the way into the spring months, and others were dried, made into apple sauce, and apple butter. Cider is also really important, but not the sweet kind we all drink in the fall.

We also grow citron melons at Firestone Farm; these look like little watermelons but are white inside – when you candy these (by cooking the rinds in a sugar syrup), you can put these into stone breads and a lot of holiday baked goods.

Dr. Howard’s Medicinal Garden (built about 1840 in Tekonsha, Michigan)

When we re-opened this building to visitors, we did a lot of research – which was easy to do, as there were a lot of original papers from Dr. Howard himself and even barrels and medicines that he used. He would pay young people to go out into the woods, pick herbs and bring them back to him to use in his medicines.

The plants we grow there are the plants that we have documented that Dr. Howard grew and picked from the woods out in what is now known as Tekonsha, Michigan (in the extreme southwest corner of Michigan, about 10 miles south of Marshall, Michigan).

Ford Home (built in 1861 in Springwells Township, Michigan)

As with several of our gardens, we have wonderful concord grapes that we grow at Henry Ford’s birthplace, alongside parsnips, brandywine and yellow pear tomatoes and different varieties of squash.

Several of these older and almost forgotten varieties of crops are starting to become popular again, and it always makes me feel good when I go to my local grocery store and see something that we grow at the Ford Home, like Hubbard Squash. I have a feeling someday those pear tomatoes will be in your Kroger store because they are just so good.

Clara Ford’s Garden of the Leavened Heart (built in 1929 in Greenfield Village)

While the gardens at our historic homes are tended by our trained historic presenters, we also have several other gardens that are tended by our Village Herbal Associates, a very strong group of volunteers that cultivate the Dr. Howard Garden, Clara Ford’s Garden of the Leavened Heart and the Burbank Production Garden; they then sell their products at the Farmer’s Market that we have each fall in Greenfield Village.

Henry Ford’s wife, Clara, was instrumental in putting this particular garden together. She didn’t have much to do with all of Greenfield Village, but Clara had that garden. It has Victorian pathways and very pretty shapes – in fact, if you look closely, you can see four arrows and four hearts; when you put them together, they make a complete circle that you can walk around.

So the next time you visit, make sure to take a few moments to look at the many varied gardens growing throughout Greenfield Village – what other elements have you noticed about each home’s garden? What similarities do you see with today’s gardening practices? What kinds of differences do you see?

Michigan, Dr. Howard's Office, food, Daggett Farmhouse, farms and farming, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, gardening