Posts Tagged education

Sustainability Through Invention at Invention Convention U.S. Nationals

One of those students was Emma Kaipainen, an 11th grader from Michigan. Emma created the Walking Shipping Container Home and won the Zero Hunger | Zero Waste Award presented by the Kroger Co. Zero Hunger | Zero Waste Foundation. Emma wanted to solve the problem of homes being destroyed by receding shorelines. Her invention is a house comprised of shipping containers, which uses electric rod actuators to power “legs” which allow the house to “walk” away from the shoreline.

The team of Nicolette Buonora and Lauren Strechay, two 9th graders from Massachusetts, were also focused on sustainability. Nicolette and Lauren created the Battery Swap and won the Most Energy Sustainable Award presented by the Avangrid Foundation. Battery Swap is a flashlight with a unique design—it has an extra switch that can divert power between two battery packs. This invention, designed with police officers in mind, solves the problem of a flashlight unexpectedly running out of power. With the Battery Swap, when the flashlight turns off, the user is able to switch to the back-up battery.

Thanks to The Kroger Co. Zero Hunger | Zero Waste Foundation and the Avangrid Foundation for funding these awards and the curriculum enhancements which helped students unlock their full invention potential!

To learn more about these inventions and our other award winners, check out the full awards ceremony below.

Continue Reading

women's history, power, environmentalism, by Mitch Hufnagel, education, innovation learning, Invention Convention Worldwide, inventors, philanthropy, childhood

Collecting Mobility: Insights from Hagerty

What aspect of mobility history (artifacts, topics, or themes) preserved at The Henry Ford feels the most significant in the current moment?

The Henry Ford’s amazing collection of self-propelled transportation machinery ranges from the diminutive 1896 Ford Quadricycle runabout that weighs just 500 pounds with an engine making four horsepower, to the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway’s gargantuan 1941 Allegheny steam locomotive weighing in at an unimaginable 1.2 million pounds and making 7,500 horsepower.

Of all these, however, the most powerful is an unassuming lime, white, and gold bus that powered the country out of its dark past of segregation into a future where laws would not discriminate against the nation’s citizens simply on the color of their skin. Especially when viewed through the prism of current events such as the Black Lives Matter movement, the 1948 General Motors (GM) bus where Rosa Parks made her stand against racial discrimination by sitting down is the most significant piece of mobility history in The Henry Ford’s collection.

The Rosa Parks Bus, on exhibit in With Liberty and Justice for All in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, is Hagerty’s pick for the most significant artifact from The Henry Ford’s collections in the current moment. / THF14922

What cars are popular with collectors right now that might eventually make their way into museum collections?

Definitely include the Tesla Roadster as the start of an incredible story about Elon Musk. It’s also the first vehicle to make electrics cool. The McLaren P1 hybrid supercar was important for establishing electrification as a must-have feature in the supercar class, making every other supercar seem outdated. Any current Formula One car, as their complex hybrid powerplants are achieving formerly unheard-of efficiency rates of over 50 percent, which is the future of the internal combustion engine … assuming it has a future. The Chevy Bolt will be remembered as the turning point for General Motors’ reputation and the industry as a whole, transforming GM from the company that notoriously “killed the electric car” (the EV1) to one of the technology’s chief proponents. The same holds true for a Volkswagen diesel, circa 2010—an enormously influential moment in which the world’s largest automaker was forced by its own actions to pivot to fully embracing electric tech, thus spurring the industry as a whole to commit to electrification.

One of Hagerty’s suggestions for cars that might make their way into museum collections is a Tesla Roadster—like this one, photographed in 2008 and owned by Elon Musk himself (photographed by Michelle Andonian). / THF55832

Are there vehicle(s), innovator stories, or mobility technologies you think The Henry Ford should add to its collections right now? Why?

An early fuel-cell vehicle, either a Honda Clarity or Toyota Mirai or Hyundai Tucson FCEV, would represent how the industry has placed bets on various technologies—and how at that moment in time, it wasn’t clear which would win out (one could debate whether it is clear even now). Obviously, a Tesla Model S with autopilot tells the story of Silicon Valley’s attempt to disrupt the auto industry through fast-paced innovation common in big tech, but unknown in the historically cautious and slow-moving auto industry. A retired Waymo or GM Cruise taxi studded with LiDAR sensors would be an example of the first attempts to commercialize autonomous vehicles.

What mobility artifacts, innovator stories, or technologies do you think The Henry Ford will be collecting in 10 years? 50 years? 100 years?

Batteries are the new frontier, as are electric motors—and the relentless drive for efficiency in both. Nothing else defines this era so aptly. Also, semiconductor manufacturing. We have seen how beholden the industry is to a component that wasn’t even used in cars just a few decades ago. The cars of today and tomorrow are just the boxes that computers come in; every automaker is turning itself into a tech company whose primary competitive advantage will be in software.

By 1990, computer engine controls were nearly universal on American automobiles. This GM computer module controlled a gasoline engine's ignition firing sequence. Hagerty notes that “The cars of today and tomorrow are just the boxes that computers come in.” / THF109463

Aluminum construction is important, too. The 2015 Ford F-150, the first aluminum-body truck, is a watershed moment for aluminum in high-volume vehicles. It is an open question now whether aluminum will spread beyond that experiment, but no automaker has made such a high-stakes gamble as Ford with the F-150. New materials and manufacturing methods are coming as the battle to reduce weight continues into the electrification era.

What aspects of mobility is Hagerty paying the most attention to right now?

The act of getting behind the wheel, twisting the key, and hitting the road is an act of personal freedom, and we believe anyone and everyone who wants to experience that should be able to. Our longstanding Hagerty Driving Experience has put thousands of young people all over North America behind the wheels of classic cars, alongside passionate owners, to teach the basics of operating a manual transmission. Through the nonprofit Hagerty Drivers Foundation, we launched the “License to the Future” program, which provides financial assistance to kids ages 14–18 to cover the expense of driver’s training. And the Hagerty Driving Academy partners with Skip Barber Racing School at dozens of events around the country to teach safe, proficient driving skills in a variety of situations.

Ensuring young people have access to driver training is important. In this 1940 photo, a young man takes a driver’s test as part of the Ford Motor Company Good Drivers League at the New York World’s Fair. / THF216125

We also regularly report on developments taking place in the realm of autonomous vehicles as a trusted voice to assure our members that this beloved activity that connects us—driving—is under no threat from the far-off future.

Will the future make owning classic vehicles more difficult or less difficult? Servicing older vehicles is already becoming harder, due to shortages in knowledge and parts, but will new technologies such as 3D printing or electric conversion mean that older vehicles will have new lives and relevance in the future?

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford. Aaron Robinson is Editor-at-Large, Kirk Seaman is Senior Editor, and Stefan Lombard is Executive Editor at Hagerty. Hagerty is an automotive enthusiast brand and the world's largest membership organization for car lovers everywhere. See Collecting Mobility for yourself in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation from October 23, 2021, through January 2, 2022.

Additional Readings:

- Henry’s Assembly Line: Make, Build, Engineer

- The Hitchcock Chair: An American Innovation

- The Changing Nature of Sewing

- Collecting Mobility: Insights from Ford Motor Company

autonomous technology, education, manufacturing, alternative fuel vehicles, African American history, Rosa Parks bus, technology, cars, by Stefan Lombard, by Kirk Seaman, by Aaron Robinson, by Ellice Engdahl

Back to School with the Henry Ford Trade School

As students everywhere settle into a new school year, let’s take a look back at the Henry Ford Trade School, founded in 1916.

The first six boys and three instructors, 1916. / THF626066

The school was formed to give young men aged 12–19 an education in industrial arts and trades. Boys who were orphans, family breadwinners, or from low-income families from the Detroit area were eligible for training and split their time between classroom and shop.

Henry Ford Trade School students and teachers in classroom, October 31, 1919. / THF284497

Students working on machinery at the Rouge Plant, 1935. / THF626060

The school started at the Highland Park plant, expanded to the neighboring St. Francis Orphans Home, and then to the Rouge plant and Camp Legion.

Henry Ford Trade School building, August 1, 1923. / THF284499

Trade School students on campus at the Rouge Plant, 1937. / THF626062

While students were receiving their education, they were also being paid an hourly wage, as well as a savings balance that was available to them at graduation. Students started off repairing tools and equipment, and as they gained more experience, moved on to working on machinery.

Student repairing goggles, Rouge Plant, 1938. / THF626064

Trade School student at the Ford Motor Company Rouge Plant, August 3, 1942. / THF245372

Students also got four weeks of vacation and daily hot lunches.

Students at lunch in the Rouge B Building cafeteria, 1937. / THF626068

The students were trained in a wide range of courses, both shop and academic, using textbooks created by the trade school. Shop courses ranged from welding to foundry work, and academic classes from English to metallurgy.

Shop Theory, 1942: cover and page 149. / THF626070, THF626075

When Ford Motor Company participated in various World’s Fairs, top trade school students were selected to demonstrate their unique style of learning.

Henry Ford Trade School demonstration, California Pacific International Exposition, San Diego, 1935. / THF209775

Students also had time for sports and clubs, including baseball, football, and radio club.

Henry Ford Trade School baseball team and manager, August 1927. / THF284507

Henry Ford Trade School football team, 1923. / THF118176

Claude Harvard with other Radio Club members, Henry Ford Trade School, March 1930. / THF272856

The Henry Ford Trade School closed in 1952. In its 36 years of operation, the school graduated over 8,000 boys from Detroit and the surrounding area. Students graduating from the trade school were offered jobs at Ford but were free to accept jobs elsewhere; among the graduates who later worked for Ford was engineer Claude Harvard (shown above). Other students went on to work in a wide range of endeavors from the automotive industry to arts and design, and even medicine and dentistry.

You can view more artifacts related to Henry Ford Trade School in our Digital Collections, or go more in-depth on our AskUs page. While the reading room at the Benson Ford Research Center remains closed at present for research, if you have any questions, please feel free to email us.

Kathy Makas is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post is based on a September 2021 presentation of History Outside the Box as a story on The Henry Ford’s Instagram channel.

school, childhood, Michigan, 20th century, sports, making, History Outside the Box, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, education, by Kathy Makas, books, archives

Interior of Henry Ford’s Private Railroad Car, “Fair Lane,” June 22, 1921 / THF148015

Beginning in 1921, Henry and Clara Ford used their own railroad car, the Fair Lane, to travel in privacy. Clara Ford designed the interior in consultation with Sidney Houghton, an interior designer based in London. The interior guaranteed a comfortable trip for the Fords, their family, and others who accompanied them on more than 400 trips between 1921 and 1942.

The view out the railcar windows often featured the landscape between Dearborn, Michigan, and Richmond Hill, Georgia, located near Savannah. The Fords purchased more than 85,000 acres in the area, starting in 1925, remaking it into their southern retreat.

On at least three occasions, Henry Ford might have looked out that Fair Lane window, observing changes in the landscape between Richmond Hill and a siding (or short track near the main railroad tracks, where engines and cars can be parked when not in use) near Tuskegee, Alabama. Henry Ford took the railcar to the Tuskegee Institute in 1938, 1941, and 1942, and Clara accompanied Henry at least twice.

Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Tuskegee, Alabama, March 1938 / THF213839

Henry first met with George Washington Carver and Austin W. Curtis at Tuskegee on March 11, 1938. A small entourage accompanied him, including Ford’s personal secretary, Frank Campsall, and Wilbur M. Donaldson, a recent graduate of Ford’s school in Greenfield Village and student of engineering at Ford Motor Company.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford on the Tuskegee Institute Campus, 1938. / THF213773

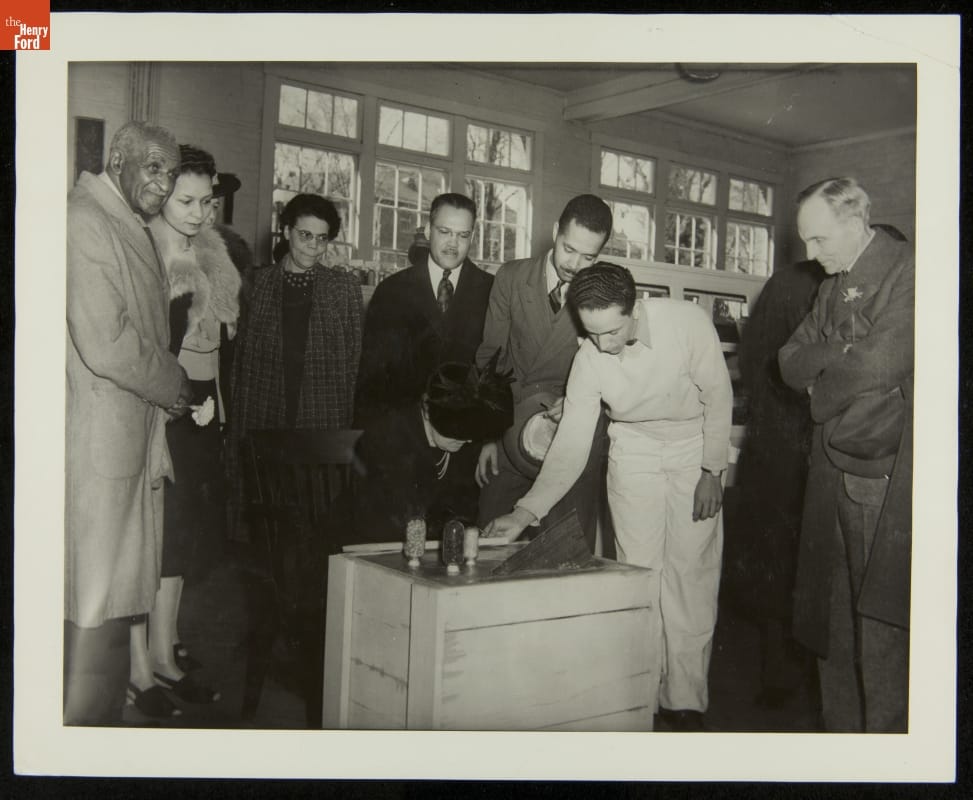

Photographs show these men viewing exhibits in the Carver Museum, installed at the time on the third floor of the library building on the Tuskegee campus (though it would soon move).

Austin Curtis, George Washington Carver, Henry Ford, Wilbur Donaldson, and Frank Campsall Inspect Peanut Oil, Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF 213794

Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, Henry Ford, and George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF214101

Clara accompanied Henry on her first trip to Tuskegee Institute, in the comfort of the Fair Lane, in March 1941. Tuskegee president F.D. Patterson met them at the railway siding in Chehaw, Alabama, and drove them to Tuskegee. While Henry visited with Carver, Clara received a tour of the girls’ industrial building and the home economics department.

During this visit, the Fords helped dedicate the George W. Carver Museum, which had moved to a new space on campus. The relocated museum and the Carver laboratory both occupied the rehabilitated Laundry Building, next to Dorothy Hall, where Carver lived. A bust of Carver—sculpted by Steffen Thomas, installed on a pink marble slab, and dedicated in June 1937—stood outside this building.

The dedication included a ceremony that featured Clara and Henry Ford inscribing their names into a block of concrete seeded with plastic car parts. The Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s most influential Black newspapers, reported on the visit in its March 22, 1941, issue. That story itemized the car parts, all made from soybeans and soy fiber, that were incorporated—including a glove compartment door, distributor cap, gearshift knob, and horn button. These items symbolized an interest shared between Carver and Ford: seeking new uses for agricultural commodities.

Clara Ford, face obscured by her hat, inscribes her name in a block of concrete during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, March 1941, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama. Others in the photograph, left to right: George Washington Carver; Carrie J. Gleed, director of the Home Economics Department; Catherine Elizabeth Moton Patterson, daughter of Robert R. Moton (the second Tuskegee president) and wife of Frederick Douglass Patterson (the third Tuskegee president); Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson; Austin W. Curtis, Jr.; an unidentified Tuskegee student who assisted with the ceremony; and Henry Ford. / THF213788

Henry Ford inscribing his name in a block of cement during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, Tuskegee Institute, March 1941 / THF213790

After the dedication, the Fords ate lunch in the dining room at Dorothy Hall, the building where Carver had his apartment, and toured the veterans’ hospital. They then returned to the Fair Lane railcar and headed for the main rail line in Atlanta for the rest of their journey north.

President Patterson directed a thank you letter to Henry Ford, dated March 14, 1941. In this letter, he commended Clara Ford for her “graciousness” and “her genuine interest in arts and crafts for women, particularly the weaving, [which] was a source of great encouragement to the members of that department.”

The last visit the Fords made to Tuskegee occurred in March 1942. The Fair Lane switched off at Chehaw, where Austin W. Curtis, Jr., met the Fords and drove them to Tuskegee via the grounds of the U.S. Veterans’ Hospital. Catherine Patterson and Clara Ford toured the Home Economics building and the work rooms where faculty taught women’s industries. Clara rode in the elevator that Henry had funded and had installed in Dorothy Hall in 1941, at a cost of $1,542.73, to ease Carver’s climb up the stairs to his apartment.

The Fords dined on a special luncheon menu featuring sandwiches with wild vegetable filling, prepared from one of Carver’s recipes. They topped the meal off with a layer cake made from powdered sweet potato, pecans, and peanuts that Carver prepared.

Tuskegee shared the Fords’ itinerary with Black newspapers, and the April 20, 1942, issue of Atlanta Daily World carried the news, “Carver Serves Ford New Food Products.” They concluded, in the tradition of social columns at the time, by describing what Henry and Clara Ford wore during the visit. “Mrs. Ford wore a black dress, black hat and gloves and a red cape with self-embroidery. Mr. Ford wore as usual an inconspicuously tailored business suit.”

Dr. Patterson wrote to Henry Ford on March 23, 1942, extending his regrets for not being at Tuskegee to greet the Fords. Patterson also reiterated thanks for “Mrs. Ford’s interest in Tuskegee Institute”—“The people in the School of Home Economics are always delighted and greatly encouraged with the interest she takes in the weaving and self-help project in the department.”

The Fords sold the Fair Lane in 1942. After many more miles on the rails with new owners over the next few decades, the Fair Lane came home to The Henry Ford. Extensive restoration returned its appearance to that envisioned by Clara Ford and implemented to ensure comfort for Henry and Clara and their traveling companions. Now the view from those windows features other artifacts on the floor of the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, in place of the varied landscapes, including those around the Tuskegee Institute, traveled by the Fords.

A view of the interior of Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car, the “Fair Lane,” constructed by the Pullman Company in 1921, restored by The Henry Ford to that era of elegance, and displayed in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF186264

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

1940s, 1930s, 20th century, Alabama, women's history, travel, railroads, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, George Washington Carver, Ford family, Fair Lane railcar, education, Clara Ford, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Memorial Paintings for Memorial Day

Americans always treasured the memory of the dearly departed, but during the era just after American independence, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, elaborate and artistic memorials were the norm. Scholars debate the reasons. Many believe that with the death of America’s most revered founding father, George Washington, in 1799, a fashion developed for creating and displaying memorial pictures in the home. Other scholars argue that the death of Washington coincided with the height of the Neoclassical, or Federal style in America. During the period after the Revolution, Americans saw themselves as latter-day Greeks and Romans. After all, they argued, the United States was the first democracy since ancient times. So, they used depictions of leaders like George Washington, along with imagery derived from antiquity.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for George Washington, by Mehetabel Wingate, 1800-1810 / THF6971

This wonderful memorial painting of George Washington was drawn in pencil and ink and painted in watercolors by a woman in Haverhill, Massachusetts, named Mehetabel Wingate. Born in 1772, Mehetabel was likely trained in painting as part of her education at an academy for genteel young ladies, much like a “finishing school” for young ladies in the 20th century. She also would have been tutored in the needle arts. The concept was to teach proper young ladies the arts as part of an appreciation for the “finer things” in life. This would prepare them for a suitable marriage and help them take their place in refined society.

In the academies, young women were taught to copy from artistic models for their work. In this case, Mehetabel Wingate copied a print engraved by Enoch G. Grindley titled in Latin “Pater Patrae” (“Father of the Country”) and printed in 1800, just after Washington’s death in 1799. Undoubtedly, she saw the print and was skilled enough to copy it in color. The image of the soldier weeping in front of the massive monument to Washington is impressive. Also impressive are the angels or cherubs holding garlands, and women dressed up as classical goddesses, grieving. One of the goddesses holds a portrait of Washington. Of course, the inscriptions tout many of Washington’s accomplishments. Mehetabel Wingate was a talented artist and ambitious in undertaking a composition as complicated as this one.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for Mehetabel Bradley Wingate, by her daughter Mehetabel Wingate, 1796 / THF237513

Fortunately, The Henry Ford owns two additional works made by Mehetabel Wingate (1772–1846). From these, we can learn a bit about her life and her family. This remarkably preserved watercolor painting memorializes her mother, also named Mehetabel, who died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1796. Young Mehetabel, who would have been 24 in 1796, is shown mourning in front of a grave marker, which is inscribed. Although it is simplified, she wears a fashionable dress in the most current style. Around her is an idealized landscape, which includes a willow tree, or “weeping” willow, on the left, which symbolized sadness. On the right is a pine tree, which symbolized everlasting life. In the background is a group of buildings, perhaps symbolizing the town, including the church, which represented faith and hope. These are standard images seen in many, if not most, American memorial pictures. Mehetabel Wingate undoubtedly learned these conventions in the young girls’ academy in her hometown of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Women in Classical Dress, 1790-1810, by Mehetabel Wingate / THF152522

The painting, above, while not a memorial painting, shows us how young ladies in the academies learned how to paint. Mehetabel seems to be practicing poses and angles, as the young ladies dressed as classical goddesses reach out to each other. It likely pre-dates both works previously shown and may have been done as a classroom exercise. As such, it is a remarkable survival.

In memory of Freeman Bartlett Jr. who died in Calcutta November the 1st 1817, aged 19 years, by Eliza T. Reed, about 1818 / THF14816

This example, painted later than Mehetabel Wingate’s work, shows the same conventions: a grieving female in front of a tomb with an inscription about the dearly departed—in this case, a young man who died at the tender age of 19 in far-off Calcutta. We also see the idealized landscape with the “weeping” willow tree and the church in the background.

Memorial Painting for Elijah and Lucy White, unknown artist, circa 1826 / THF120259

The painting above, done a few years later, shows some of the variations possible in memorial pictures. Unlike the previous examples, painted on paper, this was painted on expensive, white silk. It commemorates two people, Elijah and Lucy White, presumably husband and wife, who both died in their sixties. We see the same imagery here as before, although the trees, other than the “weeping” willows, are so abstract as to be difficult to identify.

Memorial Painting for Sarah Burgat, J. Preble, 1826 / THF305542

The example above represents a regional approach to memorial paintings. German immigrants to Pennsylvania in the late 1700s and early 1800s brought an interesting, stylized approach to their memorial paintings that have come to be known as “Fraktur.” The urn that would be seen on top of the monument in the previous examples now takes center stage, and is surrounded by symmetrically arranged birds. What we are seeing here is a combination of New England imagery, such as the urn, with Pennsylvania German imagery, such as the stylized birds. We know that this work was made in a town called Paris, as the artist, J. Preble, signed it in front of her name. There are two possible locations for Paris—one in Stark County, Ohio, and the other in Kentucky. Both had sizeable German immigrant populations in the 1820s. As America was settled and people moved west in the early 19th century, cultural practices melded and merged.

By the 1840s and 1850s, the concept of the memorial painting came to be viewed as old-fashioned. The invention of photography revolutionized the way folks could save representations of loved ones and friends. By the middle of the 19th century, these paintings were viewed as relics from the past. But in the early 20th century, collectors like Henry Ford recognized the historic and artistic value of these works and began to collect them. As a uniquely American art, they provide insight into the values of Americans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, 19th century, 18th century, women's history, presidents, paintings, making, home life, holidays, education, by Charles Sable, art

Welcome New Board of Trustees Members

What is your personal connection to The Henry Ford? For many, it’s the memories that have been made during visits to the museum and village. Others, it’s the stories told, artifacts observed, or the people who paved the way for future generations. For Linda Apsey, it was Thomas Alva Edison—his commitment to the utility industry, collaboration with Henry Ford, and future electrification of our society. For Carla Walker-Miller, it is the outreach that The Henry Ford is doing with Detroit Public Schools, the Rosa Parks Bus, and the story that sheds light on the importance of equality, diversity, and inclusion.

While each connection is different, they both share a common theme—access to education, history, and innovation for all, regardless of background or barrier. At this time in our institution’s history, we believe that both leaders will bring invaluable knowledge and perspective based on their experiences. These women are truly remarkable individuals who value our mission and will inspire others for generations to come.

Linda Apsey is currently the President and CEO of ITC Holdings Corp. and is responsible for the company’s strategic vision, business operations, and all subsidiaries. She has held many roles throughout her career that have shaped her into the successful businesswoman she is today. Before she was President and CEO, she served as Executive Vice President and Chief Unit Officer at ITC Holdings Corp.

Linda Apsey is inspired by the stories The Henry Ford can tell with its collections related to Thomas Edison, including his patent model for the electrical distribution system. / THF154126

Apsey is most looking forward to Invention Convention Worldwide. “Invention Convention provides kids across the country with a space and place for imagination to come to life. And that is amazing to observe and be part of!” This program at The Henry Ford allows young minds to tap into their can-do spirit and engage with other students and professionals throughout the world. Invention Convention is one of the unique, educational programs and initiatives that The Henry Ford is using to emphasize the importance of learning and access to education. “THF has developed many exciting programs to tap into the energy, passion, and creative minds of our future generations through teaching, experimentation, and competitions, all of which provides opportunity, access, and collaboration for growing minds.”

Carla Walker-Miller is the founder and CEO of Walker-Miller Energy Services. She is a changemaker in the energy industry and strives to inspire those she encounters. Walker-Miller Energy Services is one of the largest energy waste reduction companies in the country founded and owned by an African American woman.

Walker-Miller is greatly inspired by the community outreach The Henry Ford (THF) is doing in metro Detroit, particularly Detroit Public Schools. “Like most people, I had no idea before I joined the board the amount of work this institution is doing and the commitment The Henry Ford has made in educating our children. The work THF is doing with Detroit Public Schools is so thoughtful and intentional and I’m amazed at the impact The Henry Ford is having.”

Carla Walker-Miller feels welcomed by the presence of the Rosa Parks Bus in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF167250

Being able to inform and educate others about the many different stories and lessons we have learned throughout American history is very important. The Henry Ford is committed to telling the stories of the brave men and women who were the catalysts for change in racial equity. Carla Walker-Miller agrees that the acquisition of the Rosa Parks Bus in the early 2000s was a monumental step for The Henry Ford. “In my heart, that acquisition felt like an acknowledgement that Black history is American history. It may as well have been a bridge, because it felt like a welcome, like a personal invitation to visit. I will never forget the photo of President Barack Obama on that bus. It spoke to me and so many other people of many races.”

Linda Apsey and Carla Walker-Miller both agree that The Henry Ford is a place that is meant to be treasured. To our current donors who believe in the mission and value of The Henry Ford, thank you! For those who may be new to The Henry Ford and are still learning about the institution, we invite you to dive deeper into our mission. For Apsey, “Investing in THF is not only an investment in our rich industrial history of innovation and automation, but more importantly an opportunity to invest in the hearts, souls, and minds of future generations. THF is a world-class institution whose history has just begun!” To Carla Walker-Miller, “The Henry Ford offers a warm introduction to this country’s history. They are committed to making the institution inclusive and accessible to all and to say, ‘Everyone is welcome here.’” We are very lucky to have these two passionate executives help take The Henry Ford to new levels and reach the hearts and minds of future generations.

Caroline Heise is Annual Fund Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Detroit, education, entrepreneurship, Invention Convention Worldwide, The Henry Ford Effect, by Caroline Heise, African American history, women's history, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Detroit native Frederick Birkhill can recount numerous memories of his time at The Henry Ford and Greenfield Village as a child. He can remember riding his bike through the village, taking in all that its history and grounds offered. Truly enamored with Liberty Craftworks, he spent most of his time there, observing the artisans perfecting their crafts.

During one school field trip, his class observed employee Neils Carlson giving a glassblowing demonstration. From five feet away, the students watched Carlson pull and shape a hot, glowing blob into a graceful swan. This was the exact moment that Birkhill fell in love with glassmaking and knew he wanted to learn everything about it. After the demonstration, he bought one of the glass swans for his mother and studied it whenever he could.

Frederick as a child with a camera, circa 1959. / Photo by Dr. F. Ross Birkhill, courtesy Frederick Birkhill

Few people can pinpoint the place where they found their passion. Frederick Birkhill can. Anyone who comes to The Henry Ford can find something that excites them and sparks their future passions. That single experience in the Glass Shop stuck with Birkhill and led him on a path to a very successful career as an artist. Because of Neils Carlson, Birkhill's thirst for knowledge took off, leading him to study in England, elsewhere in Europe, and at what is now the College for Creative Studies in Detroit and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

In the early years of his career, Birkhill was an employee of Greenfield Village and worked in the Tintype Studio. During his tenure, he was able to study and learn about glassblowing, stained glass, photography, daguerreotypes, and tintypes from various artisans around Liberty Craftworks and metro Detroit. At the time, The Henry Ford was one of the only places in the United States where one could learn about tintype photography and other specialized crafts. Birkhill created some of his first daguerreotype photos of scenes at The Henry Ford. One of those early daguerreotypes of Greenfield Village's Farris Windmill was later acquired by the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. "The Windmill at Greenfield Village, 1972,” daguerreotype created by Frederick Birkhill, in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History / Photo courtesy Frederick Birkhill

"The Windmill at Greenfield Village, 1972,” daguerreotype created by Frederick Birkhill, in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History / Photo courtesy Frederick Birkhill

In addition to learning about different media during his time working in the village, Birkhill was able to use his skills and artistry to teach an array of subjects at The Henry Ford, including classes he developed on the history of glass and stained glass.

Birkhill also collaborated with David Grant Maul, another former employee. Birkhill acquired a special tool from Maul that allowed him to hold hot glass so he could effectively complete flame-worked glass objects. This tool was the catalyst for a successful career in flame-worked glass and furnace glass. Our Glass Shop includes a furnace that allowed Birkhill to learn both specialties.

Frederick Birkhill is a renowned artist, inventor, educator, and historian whose international career continues to this day. His work can be seen at the Corning Museum of Glass, Museum of Arts and Design, Detroit Institute of Arts, the Mint Museum, the Smithsonian, and the Stamelos Gallery Center at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, as well as in private collections around the world. Never once has Birkhill forgotten the place that sparked his curiosity and put his ideas into motion—The Henry Ford. Frederick Birkhill flameworking in his studio. / Photo by Henry Leutwyler, courtesy Frederick Birkhill

Frederick Birkhill flameworking in his studio. / Photo by Henry Leutwyler, courtesy Frederick Birkhill

Now, after several decades as a glass artist, an artist's monograph, Glassworks: The Art of Frederick Birkhill, has been published by The Artist Book Foundation. An extensive colorplate section includes the lavish photography of Henry Leutwyler, showcasing Birkhill's work in complex detail as well as his artistic mastery of glass. A copy now resides in The Henry Ford's Benson Ford Research Center. We are honored to have Frederick and his wife, Jeannie, as friends of The Henry Ford.

Caroline Heise is Annual Fund Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery

- "Devils Blowing Glass" by Lucio Bubacco, 1997

- Now Open: Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery

- Western Interactions with East Asia in the Decorative Arts: The 19th Century

21st century, 20th century, Dearborn, The Henry Ford staff, The Henry Ford Effect, photography, Michigan, making, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, glass, education, Detroit, by Caroline Heise, books, art

Connecting Sustainability to Invention

Through an initiative funded by The Kroger Co. Zero Hunger | Zero Waste Foundation and The Avangrid Foundation, the Invention Convention Worldwide team at The Henry Ford has created a pathway to connect sustainability to invention for our students in the classroom. Through the lens of biomimicry, student inventors examine how some of humanity’s greatest inventions have been formed by the world around them and how they can tap into nature to find sustainable solutions, while problem solving by using biomimicry.

A great example of this comes from Florida fifth grader and 2020 Invention Convention participant Xavier Baquero-Iglesias and his invention SoleX Turf: Good for Your Sole, Good for Your Plant. SoleX Turf is an invention that uses the principle of photosynthesis and the practice of biomimicry. This artificial turf uses the principles of photosynthesis to collect and create energy from the sun while cooling the temperature of the turf to be more enjoyable for players.

childhood, philanthropy, inventors, Invention Convention Worldwide, innovation learning, educational resources, education, by Samantha Johnson, by Mitch Hufnagel, by Devin Rittenhouse, by Alisha Hamblen

Let’s Tech Together

Illustration by Sylvia Pericles.

Welcome to the digital era. Now what?

In the fall of 2020, for the first time, an entire generation started school on a screen. As the new coronavirus abruptly cut many of us off from the world outside our homes, for those of us fortunate enough to enjoy digital communication tools, the Internet has become one of the most essential tools for surviving the COVID-19 pandemic. As sci-fi and scary as this may seem, there is also an opportunity here to transform—again—the Internet.

As COVID-19 continues to dramatically upend our lives, an ever-evolving digital world pushes us to rethink the purpose of the Internet and challenges us to re-create our digital and political lives as well as the Internet itself. The challenge is ensuring that all people will have the skills, knowledge and power to transform the Internet and shift its dependence on a commerce- and clickbait-driven economic model to become instead a universally guaranteed utility that serves people’s needs and allows creativity to flourish.

Societal Reflection

This challenge has been a long time coming. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Internet was on questionable ground. In early 2020, misinformation campaigns, privacy breaches, scams, and trolls proliferated online. When COVID-19 hit and the world was forced to shift the important tasks of daily life online, we saw (again) how digital inequalities persist—forcing poor and vulnerable communities to rely on low-speed connections and cheaper devices that can’t handle newer applications.

The Internet is a reflection of who we are as a society. We know that there are people who scam and bullies who perpetuate injustice. But there is also beauty, creativity, and brilliance. The more perspectives there are shaping this digital era, the more potential we have to tap the best parts of us and the world.

There is no silver bullet that will keep violence or small-mindedness at bay—online or off—but I know from 13 years of working on digital justice in Detroit that teaching technology is the first step toward decolonizing and democratizing it.

A City’s Story

Over the years, Detroit has faced many economic hardships, which has meant that digital access has too often taken a back seat. Bill Callahan, director of Connect Your Community 2.0, compiled data from the 2013 American Community Survey and found that Detroit ranked second for worst Internet connectivity in the United States.

Following that report, in 2017 the Quello Center of the Department of Media and Information at Michigan State University reported that 33% of Detroit households lacked an Internet connection, fixed or mobile. Yet the world had already moved online.

By 2011, many government agencies had transitioned away from physical spaces, making social services only accessible via the Internet. My colleagues and I at Allied Media Projects (a nonprofit that cultivates media strategies for a more just, collaborative world) understood that access to and control of media and technology would be necessary to ensure a more just future. As Detroiters, we needed to figure out how to create Internet access in a city that was flat broke and digitally redlined by commercial Internet providers. We also needed to address the fact that many Detroiters who had never before used digital systems had a steep learning curve ahead of them.

The question we asked our communities, and answered collectively, originated from and addressed Detroit’s unique reality: What can the role of media and technology be in restoring neighborhoods and creating new economies based on mutual aid?

Illustration by Sylvia Pericles.

To answer this question, the concept and practice of community technology—a method of teaching and learning technology with the goals of building relationships and restoring neighborhoods—emerged. If we want to harness the potential of the digital future ahead of us, we need to reshape our current relationships with the digital world. We need to understand how it works, demand our rights within it, and be aware of how digital tools shape our relationships with each other and with the larger world. Ultimately, the goal of community technology is to remake the landscape of technological development and shift the power of technology from companies to communities. The place where this begins is by rethinking our digital literacy and tech education models.

Community technology is inspired by the citizenship schools of the Civil Rights movement. Founded by Esau Jenkins and Septima Clark on Johns Island, South Carolina, in the 1950s, citizenship schools taught adults how to read so that they could pass voter-registration literacy tests. But under the innocuous cover of adult-literacy classes, the schools actually taught participatory democracy and civil rights, community leadership and organizing, practical politics, and strategies and tactics of resistance and struggle.

I saw a through line from the issues that encouraged citizenship schools to emerge in the 1950s to the struggles that Detroit faced in the early 2000s. In the 21st century, communities with high-speed Internet access and high levels of digital literacy enjoyed a competitive advantage. The denial of these resources to low-income and communities of color compounded the existing inequality and further undermined social and economic welfare in those neighborhoods.

Like the citizenship schools, community technology embraces popular education, a movement-building model that creates spaces for communities to come together in order to analyze problems, collectively imagine solutions, and build the skills and knowledge required to implement visions. This educational model structures lessons around the goal of immediately solving the problem at hand. In the citizenship schools, lessons were planned around the goal of reading the U.S. Constitution. Along the way, participants developed the profound technical and social skills needed to solve the problem.

In 2008, when I first started teaching elders in Detroit how to use and understand the Internet, it was always hard to know where to start. There were so many things to do online. The first question I asked was: “What do you wish you could do with the Internet?” Oftentimes, folks wanted to be able to view images of their grandchildren that had been sent to their email, or they would want to communicate with loved ones across the seas. It would be nearly impossible for me to teach a class that attended to all of those individual needs while keeping everyone engaged.

I wondered: If I taught problem-solving rather than teaching technology, could I support the same elder who couldn’t view a digital photo of their grandchild to build and install Wi-Fi antennas and run an Internet service provider (ISP) in their neighborhood?

As impossible as that may sound, it worked. In 20 weeks, I saw former Luddites work with their neighbors to build wireless networks. This curriculum went on to shape the Equitable Internet Initiative, which has trained over 350 Digital Stewards throughout Detroit, New York, and Tennessee.

Illustration by Sylvia Pericles.

Digital Liberation

Over the eight years I ran the Digital Stewards Program, what I realized is that relevance can engage someone to learn, but curiosity is what cultivates the kind of lifelong learning that leads to liberation.

Citizenship schools remind me that liberation is not a product of having learned a skill but rather the continued ability to participate in and shape the world to meet your and your communities’ needs. Becoming a lifelong learner of technology—and aspiring constantly to use it for liberatory ends—is essential because technology is constantly changing.

Every software program I ever learned in college is now obsolete. To meaningfully participate in the digital era, we need to be able to adapt technology to meet our needs rather than change ourselves to adapt to new technologies.

In order to cultivate the agency and self-determination necessary to rescue this digital era from corporations and trolls, we will need to change how we as a society pass on knowledge and how—and for whom—we cultivate leadership and innovation. Too often, technological knowledge is presented as a pathway for individual advancement through participation in a digital economy that further consolidates power and wealth for corporations. During this time of physical isolation, how do we change the experience of being forced into endless video meetings and classrooms into something more like inhabiting and co-creating a digital commons? Can we create environments that allow people to engage with technology from a community context rather than as distanced individuals stuck staring at our screens?

The Internet’s culture is currently being shaped by corporations. Social media platforms, ISPs, and algorithms control our movements through almost all online space. Can we remake the Internet into a community that we can all inhabit, and move away from the metaphor of the Internet as an information superhighway? Perhaps we can begin to build the equivalent of sidewalks, public parks, and bike lanes.

As a generation faces an unprecedented year of school online, we would be wise to realize that this is an opportunity for all of us to learn together and become both more critical of how we engage technology and more aware of what we see is lacking. How do we want to form a community online, navigating, creating, and adapting online spaces for our collective survival?

Perhaps, unwanted though it is, the global pandemic can inspire us to finally create a digital world that is befitting of our time and presence there—and can inspire the justice, equality, and hope that our IRL world so badly needs right now.

This post was adapted from an article by Diana J. Nucera that originally appeared in the January–May 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine. Nucera, aka Mother Cyborg, is an artist, educator, and community organizer who explores innovative technology with communities most impacted by digital inequalities. Post edited by Puck Lo; illustrations by Sylvia Pericles.

Civil Rights, education, COVID 19 impact, Michigan, Detroit, women's history, African American history, technology, by Diana J. Nucera, The Henry Ford Magazine

Lyn St. James, photographed by Michelle Andonian, 2008 / THF58574

Racing Career

Lyn St. James was watching from afar when Janet Guthrie was trying to break into Indy car and stock car racing. At the time, St. James was a part-time competitor chasing a Sports Car Club of America road-racing national championship in a Ford Pinto.

“I was excited and pumped about my racing, and I watched her on the television and thought, ‘God, she’s struggling and nobody wants her there,’” St. James recalled. “She didn’t smile very much, and it made me say, ‘Why would I want to do that? Why would I want to put myself in that kind of situation when I was having so much fun?’”

This racing helmet worn by Lyn St. James is going on display in Driven to Win: Racing in America. / THF176437

In the early 1980s, Kelly Services sponsored the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) American Challenge championship and paid bonuses to female drivers. St. James parlayed an opportunity in that series, along with a chance encounter with legendary Ford executive Walter Hayes, into a highly successful relationship with Ford that produced six wins in IMSA competitions, including class victories at Daytona and Sebring, prior to shifting her focus to Indy cars. She is also the only woman to win an IMSA GT race driving solo.

Lyn St. James at IMSA, Watkins Glen, NY, 1985 / THF69459

“I wanted to test-drive one, just to experience the peak of race car performance,” she said. “I was just in heaven. I had set speed records in a stock car at Talladega, and in comparison, it felt numb. Dick Simon [IndyCar team owner] was very supportive, and that was a turning point. I wrote to 150 companies over four years seeking support. J.C. Penney was the 151st, but the first one that said yes.”

Finally, in 1992, St. James became the first woman to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 since Guthrie last had, 15 years earlier. St. James finished 11th in the race, claiming Rookie of the Year honors (the first woman to do so). In 1994, she out-qualified reigning Indy car champion Nigel Mansell at Indy; she made a total of seven Indianapolis starts, with her last in 2000. She has been inducted into the Sports Car Club of America and the Florida Sports halls of fame, and held 21 international and national closed-circuit speed records over a 20-year period.

Lyn St. James’s Indy 500 history from 1992 to 2000. / THF284826

Mentor of Motorsports

St. James still occasionally competes in vintage races, and in addition is a speaker, author, philanthropist, and coach, but spends most of her time mentoring female drivers. Her foundation’s driver development program has graduated more than 230 participants over the last 25 years, including then-future Indy car drivers Sarah Fisher and Danica Patrick.

Lyn St. James at her Complete Driver Academy, which provided a comprehensive education and training program for talented women race car drivers who aspired to attain the highest levels in motorsports, in Phoenix, Arizona in 2008 (photograph by Michelle Andonian). / THF58682

“It’s sad that leaders in motorsports have not figured out that the car levels the playing field for everyone,” St. James said. “The leaders have missed an opportunity to show how female involvement in racing really represents society. Women can perform and compete on an equal level.”

Involvement with The Henry Ford and

Driven to Win

In 2008, a small crew from The Henry Ford traveled to Phoenix, Arizona, to visit a race car driver academy for women. The institution, called Complete Driver Academy, was established by Lyn St. James in 1994 to help identify potential champion female drivers and provide the tools they needed to further their careers. The Henry Ford interviewed St. James there as part of its Visionaries on Innovation collection of video interviews, which also features other racing legends such as Mario Andretti.

Lyn St. James’ 1992 Indianapolis 500 "Rookie of the Year" trophy will be on exhibit in Driven to Win. / THF176451

In addition to documenting St. James’ oral history, The Henry Ford has many artifacts from her racing career in its collections—some of which will be on display in the new Driven to Win: Racing in America permanent exhibition in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, where St. James is a showcased driver. “Lyn has been an adviser to the exhibit going back more than ten years,” said Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson. “From the start, she has offered her help and advice, including connecting us with innovators like motorsports training expert Jim Leo of PitFit Training in Indiana.”

Among the racing-related artifacts from St. James that will be on display in Driven to Win: her helmet, driving suit, HANS (head and neck support) device, and Rookie of the Year trophy from the 1992 Indy 500, where she became the first woman to win that title. You can also explore many more artifacts related to St. James’ career in our Digital Collections.

This post was adapted from an article by John Oreovicz that originally appeared in the January–May 2020 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Indiana, 21st century, 20th century, women's history, The Henry Ford Magazine, racing, race car drivers, Indy 500, Henry Ford Museum, education, Driven to Win, cars, by John Oreovicz