Posts Tagged driving america

1931 Duesenberg Model J Convertible Victoria: The World’s Finest Motorcar?

THF90796

Fred Duesenberg set out to build an automotive masterpiece. Its superlative engineering included a 265-horsepower engine that could push the car to a 116-mph top speed. Duesenberg built only 481 Model Js between 1928 and 1935. No two are identical because independent coachbuilders crafted each body to the buyer’s specifications. Is it the world’s finest? One thing is certain--the Model J will always be in the running.

Duesenberg ads associated the car with wealth and privilege. / THF101796, THF83515

These are a few of the many body styles offered in a 1930 catalog. But that was just a starting point--each car was customized to the owner’s taste. / THF83517, THF83518, THF83519

The Henry Ford’s Duesenberg has luggage designed to fit the trunk precisely. / THF90800

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1937 Cord 812 Convertible: Unusual Technology, Striking Style

- 1903 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Runabout

- 1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One

- 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

20th century, 1930s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

1956 Continental Mark II Sedan: “The Excitement of Being Conservative”

THF90723

In an era of extreme automotive styling, the Mark II was elegantly understated. Its advertising slogan, “the excitement of being conservative,” confirmed that Mark II’s appeal depended not on chrome, but rather on flawless quality control, extensive road testing, shocks that adjusted to speed, and power steering, brakes, windows, and seats. Not understated was the $10,000 price. Owned by VIPs like Frank Sinatra and Nelson Rockefeller, it was the most expensive American car you could--or couldn’t--buy.

William Clay Ford (left) reviews a clay model of the Mark II in 1953. He inherited a passion for styling from his father, Edsel Ford, and directed the Mark II’s design and development. / THF112905

The dashboard--luxurious in 1956--featured an instrument panel inspired by airplanes, with a pushbutton radio, watch-dial gauges, and throttle-style climate control levers. / THF113250

Like the car, advertising was understated. This Vogue magazine ad links the car with classic design in architecture and fashion. / THF83341

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

- The Henry Ford’s Tollbooths and the Cost of Good Roads

- 1981 Checker Marathon Taxicab

20th century, 1950s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, cars

1931 Bugatti Type 41 Royale Convertible: Unmatched Style and Luxury

THF90825

Longer than a Duesenberg. Twice the horsepower of a Rolls-Royce. More costly than both put together. The Bugatti Royale was the ultimate automobile, making its owners feel like kings. It is recognized as the epitome of style and elegance in automotive design. Not only did it do everything on a grander scale than the world’s other great luxury cars, it was also rare. Bugatti built only six Royales, whereas there were 481 Model J Duesenbergs and 1,767 Phantom II Rolls-Royces.

Ettore Bugatti formed Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. in 1909. His cars were renowned for their exquisite design and exceptional performance—especially in motor racing. According to lore, Bugatti was at a dinner party when a woman compared his cars unfavorably with those of Rolls-Royce. In response, he designed the incomparable Royale.

The Royale's elephant mascot was based on a sculpture by Rembrandt Bugatti, Ettore Bugatti's brother, who died in 1916. / THF90827

Because Bugatti Royales are so rare, each has a known history. This is the third Royale ever produced. Built in France and purchased by a German physician, it traveled more than halfway around the world to get to The Henry Ford. Here is our Bugatti’s story.

Joseph Fuchs took this 1932 photograph of his new Bugatti, painted its original black with yellow trim. His daughter, Lola, and his mechanic, Horst Latke, sit on the running board. /THF136899

1931: German Physician Joseph Fuchs orders a custom Royale. Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. builds the chassis in France. Its body is crafted by Ludwig Weinberger in Munich, Germany.

1933: Fuchs leaves Germany for China after Hitler becomes chancellor, taking his prized car with him.

1937: Japan invades China. Fuchs leaves for Canada—again, with his car. Having evaded the furies of World War II, Fuchs and his Bugatti cross Canada and find a home in New York City.

1938: A cold winter cracks the car’s engine block. It sits, unable to move under its own power, for several years.

1943: Charles Chayne, chief engineer of Buick, buys the Bugatti. He has it restored, changing the paint scheme from black and yellow to white and green.

1958: Now a General Motors vice-president, Chayne donates the Bugatti to Henry Ford Museum.

1985: For the first time, all six Bugatti Royales are gathered together in Pebble Beach, California.

The first-ever gathering of all six Bugatti Royales thrilled the crowds at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in 1985. They are the ultimate automotive expression of style and luxury. / THF84547

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1903 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Runabout

- Fozzie Bear’s 1951 Studebaker Commander

- 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air Convertible

- Mimi Vandermolen and the 1986 Ford Taurus

20th century, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

1908 Stevens-Duryea Model U Limousine: What Should a Car Look Like?

THF90991

Early car buyers knew what motor vehicles should look like--carriages, of course! But automobiles needed things carriages didn’t: radiators, windshields, controls, horns, and hoods. Early automakers developed simple solutions. Brass, often used for carriage trim, was adopted for radiators, levers, and horns. Windshields were glass plates in wood frames. Rectangular sheet metal covers hid engines. The result? A surprisingly attractive mix of materials, colors, and shapes.

Although the Stevens-Duryea Company claimed its cars had stylish design, most early automakers worried more about how the car worked than how it looked. / THF84913

To build a car body, early automakers had to shape sheet metal over a wooden form. Cars made that way, like this 1907 Locomobile, often looked boxy. / Detail, THF84914

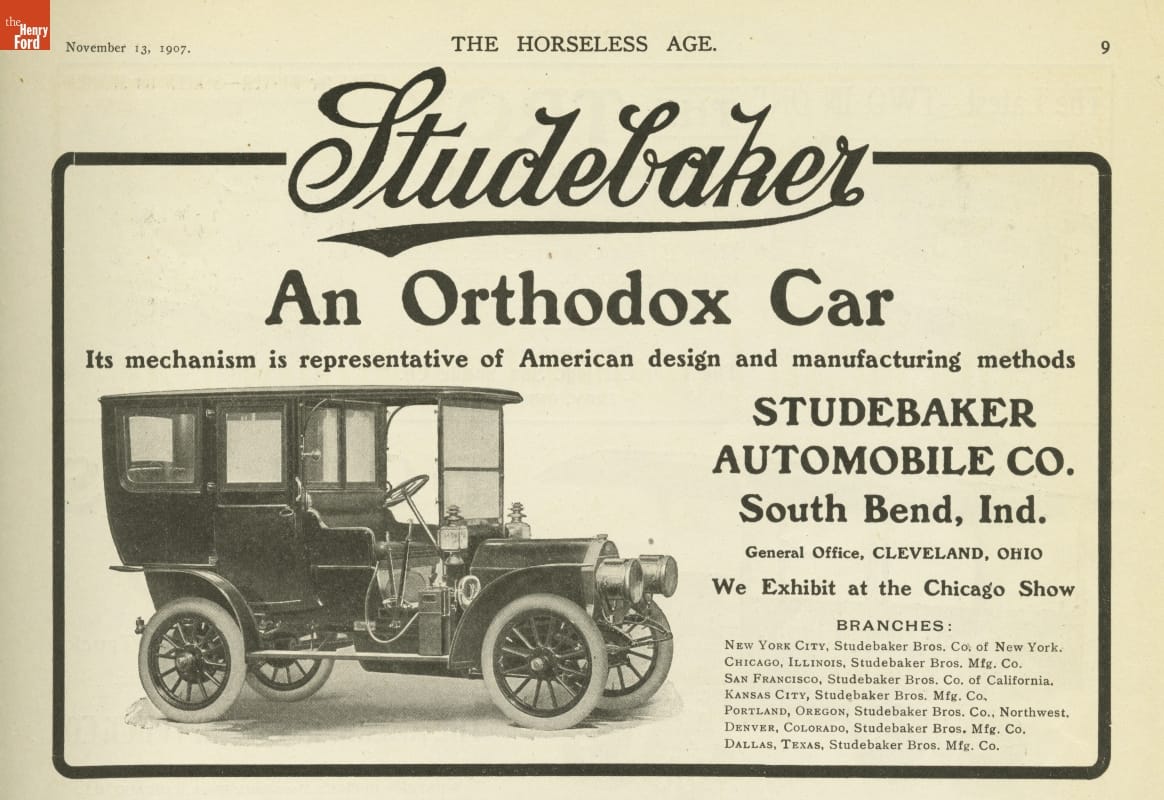

Some early automobiles looked good. But even the attractive ones looked like an assembly of parts, like the Studebaker shown in this 1907 ad. / THF84915

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- Women in the War Effort Workforce During WWII

- 2002 Toyota Prius Sedan: An Old Idea Is New Again

- 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

20th century, 1900s, limousines, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, design, cars

1937 Cord 812 Convertible: Unusual Technology, Striking Style

THF90811

Although it wasn’t the most expensive car of its day, the 1937 Cord was pricey. But its Depression-era buyers were well-off and didn’t mind a stylish car that attracted attention. The Cord’s swooping fenders, sweeping horizontal radiator grille, and hidden headlights were unlike anything else on American highways. And although it wasn’t the first, the Cord was the only front-wheel-drive production car available in America for the next three decades.

This 1937 Cord catalog shows the sedan version of the car. THF83512

The company’s definition of luxury included not only the Cord’s styling but also its comfort, its ease of driving and parking, and the advantages of front-wheel drive. THF83513

Customers who wanted even more luxurious touches could buy accessories from the dealer. The Cord Approved Accessories catalog for 1937 included some items now considered basics, such as a heater, a windshield defroster, and a compass. Image (THF86243) taken from copy of catalog.

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz Convertible: Is This the Car for You?

- Noyes Piano Box Buggy, about 1910: A Ride of Your Own

- Douglas Auto Theatre Sign, circa 1955

- 2016 General Motors First-Generation Self-Driving Test Vehicle

20th century, 1930s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

An early McDonald’s after the menu change and before the iconic Golden Arch redesign. THF125822

If you do an Internet search on the date and place of the first McDonald’s, chances are you’ll get 1955, Des Plaines, Illinois. But that was actually the first McDonald’s franchised by milkshake machine salesman Ray Kroc.

The first real McDonald’s was created by Richard (“Dick”) and Maurice (“Mac”) McDonald in San Bernardino, California, on May 15, 1940. Located on Route 66 and based upon a food stand opened by their father a few years earlier, Dick and Mac’s “McDonald’s Bar-B-Que” was typical of car-hop type drive-in restaurants of its day.

The big shift from a joint selling barbecue ribs, beef, and pork sandwiches on china plates to the McDonald’s we know today occurred in 1948. Dick and Mac were tired of trying to keep capable cooks and reliable carhops on staff. And the teenagers were driving them crazy—hanging out, breaking the china, and keeping other customers away. So they closed their restaurant, fired the carhops, and a few months later, introduced a whole new “Speedee Service System.” This radical new concept featured a limited menu, walk-up service, an assembly-line system of food production, and drastically reduced prices. Five years later, milkshake machine salesman Ray Kroc recognized a “golden” concept when he saw one. He franchised the concept with their name across the country, especially in the new suburban neighborhoods across the Midwest.

McDonald’s sign, 1960, in the Driving America exhibition, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. THF151145

Neon signs like this one, with a single “golden” arch and the logo of Speedee, the hamburger-headed chef, flashed in front of early McDonald’s franchises. The instantly recognizable design was drawn by Richard McDonald in 1952, first applied to a McDonald's restaurant in 1953, and then co-opted by Ray Kroc when he began franchising the restaurants in 1954. It became the corporate logo in 1963, after Kroc bought out the McDonald brothers in 1961. This particular sign lit up Michigan’s second McDonald’s, located in Madison Heights.

The McDonald’s innovative Speedee Service System, reduced-price menu, and recognizable Golden Arches set the standard for numerous other fast food establishments to come. During the 1970s, Happy Meals raised the bar again. McDonald’s continues to be at the forefront of new trends in the fast food industry.

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

- 1937 Cord 812 Convertible

- Douglas Auto Theatre Sign, circa 1955

- Driving America

Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, Michigan, popular culture, by Donna R. Braden, food, restaurants

Diners: An American Original

In 1984, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation acquired an old, dilapidated diner. When Lamy’s Diner—a Massachusetts diner from 1946—was brought into the museum, it raised more than a few eyebrows. Was a common diner, from such a recent era, worthy of restoration? Was it significant enough to be in a museum?

Happily, times have changed. Diners have gained newfound respect and appreciation. A closer look at diners reveals much about their role and significance in 20th-century America.

Diner, Wason Mfg. Co., interior, 1927-9. THF228034

Diners changed the way Americans thought about dining outside the home. A uniquely American invention, diners were convenient, social, and fun.

Horse-drawn lunch wagon, The Way-side Inn. THF38078

Diners originated with horse-drawn lunch wagons that came out on city streets at night, providing food to workers. They also attracted “night owls” like reporters, politicians, policemen, and supposedly even underworld characters!

Peddler’s cart: NYC street scene, 1890-1915. THF241185

Most people agree that horse-drawn lunch wagons evolved from peddler’s carts, like those shown here on this New York City street.

Cowboys at the Chuck Wagon, Crazy Woman Creek, Wyoming Territory, 1885. THF124569

Some people even think that cowboy chuck wagons helped inspire lunch wagons. Here’s a cool scene of a group of cowboys in Wyoming from 1885. Take a look at the fully outfitted chuck wagon in the picture above.

The Owl Night Lunch Wagon. THF88956

The Owl Night Lunch Wagon in Greenfield Village is thought to be the last surviving lunch wagon in America!

Visitors at the Owl Night Lunch Wagon. THF113945

Henry Ford ate here as a young engineer at Edison Illuminating Company in downtown Detroit. In 1927, Ford acquired the old lunch wagon to become the first food operation in Greenfield Village. Notice the menu and clothing worn by the guests.

In this segment of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, you can watch Mo Rocca and me eating hot dogs with horseradish at the Owl—just like Henry Ford might have done back in the day!

Walkor Lunch Car, c. 1918. THF297240

When cars increased congestion on city streets, horse-drawn lunch wagons were outlawed. To stay in business, operators had to re-locate their lunch wagons off the street. Sometimes these spaces were really cramped.

County Diner, 1926. THF297148

By the 1920s, manufacturers were producing complete units and shipping them to buyers’ specified locations. Here’s a nice exterior of one from that era.

Hi-Way Diner, Holyoke, Mass., ca. 1928. THF227976

These units were roomier and often cleaner than the by-now-shabby lunch wagons. To make them seem more upscale, people began calling these units “diners,” evoking the elegance of railroad dining cars.

Ad with streamlined diner, railroad, and airplane, 1941. THF296820

As more people got used to eating out in diners, more diners were produced. By the 1940s, some diners took on a streamlined form—inspired by the designs of the new, modern streamlined trains and airplanes.

Lamy’s Diner. THF77241

By the 1940s, there were so many diners around that this era became known as the “Golden Age of Diners.” This is where our own Lamy’s Diner comes in. It was made in 1946 by the Worcester Lunch Car Company of Massachusetts. You may not be able to get a cup of coffee and a piece of pie inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation right now, but you can visit Lamy’s virtually through this link.

Move of diner from Hudson, Mass., 1984. THF124974

The Henry Ford acquired Lamy’s Diner in 1984, then restored it for a new exhibition, “The Automobile in America Life” (1987). Here’s an image of it being lifted for its move to The Henry Ford.

Lamy’s Diner on original site. THF88966

Lamy’s Diner was originally located in Marlborough, Mass. Here’s a photograph of it on its original site. But, like other diners, it moved around a lot—to two other towns over the next four years.

Snapshot of Clovis Lamy in diner, ca. 1946. THF114397

Clovis Lamy was among other World War II veterans who dreamed of owning his own business when the war was over, and diners promised easy profits. As you can see here, he loved talking to people from behind the counter. From the beginning, Lamy’s Diner was a hopping place all hours of the day and night. You can read the whole story of Clovis Lamy and his diner in this blog post.

Lamy’s as a working restaurant in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

In 2012, Lamy’s became a working restaurant again—inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Nowadays, servers even wear diner uniforms that let you time-travel back to the 1940s. A few years ago, the menu was revamped. So now you can order frappes (Massachusetts-style milkshakes), New England clam chowder, and some of Clovis Lamy’s original recipes. Read more about the recent makeover here.

View of a McDonalds restaurant and sign, 1955. THF125822

Diners declined when fast food restaurants became popular. McDonald’s was first, with food prepared by an assembly-line process, paper packaging, and carry-out service. Check out this pre-Golden Arches McDonald’s.

Mountain View steel diner, Village Diner, Milford, PA, c. 1963. THF297276

The 1982 movie Diner helped spur a new revival in diners, as some people got tired of fast food and chain restaurants. Here’s an image of a Mountain View steel diner, much like the one used in that movie.

Dick Gutman in front of a Kullman diner, 1993. THF297029

One person was particularly instrumental in documenting and helping revive the interest in diners. That’s diner historian Richard Gutman. Here he is in 1993 with camera in hand—in front of a diner, of course. We are thrilled that last year, Richard donated his entire collection of historic and research materials to The Henry Ford—including thousands of slides, photos, catalogs, postcards, and diner accouterments!

Modern Diner, Pawtucket, RI, 1974 slide. THF296836

Richard not only documented existing diners but helped raise awareness of the need to save diners from extinction. The Modern Diner, shown here, was the first to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places (1978).

Robbins Dining Car, Nantasket, Mass., ca. 1925. THF277072

Be sure to check out our Digital Collections for many items from Richard’s collection already online.

Diners continue to have popular appeal. They offer a portal into 20th-century social mores, habits, and values. Furthermore, they represent examples of American ingenuity and entrepreneurship that connect to small business startups and owners today.

This post was originally part of our weekly #THFCuratorChat series. Follow us on Twitter to join the discussion. Your support helps makes initiatives like this possible.

Additional Readings:

20th century, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden, #THFCuratorChat

2002 Toyota Prius Sedan: An Old Idea Is New Again

In the early 21st century, the threat of global warming and the end of cheap gas worried many drivers. Among drivers’ options was buying a gasoline-electric hybrid such as this Prius. The hybrid concept was over 100 years old, but new technologies made it practical. Hybrids cost more but reduce fuel consumption, which leads to lower emissions.

Toyota introduced the Prius in Japan in 1997 and then worldwide in 2000. The price was steep for a compact, but tax credits offset some of the cost, and drivers got a little environmental peace of mind in the deal, too. THF206198

One of the selling points of modern hybrid cars is that computers do all the work. But many owners like monitoring the car’s operation on the in-dash screen and enjoy minimizing fuel usage. This image shows the dashboard of a 2004 Prius. THF101127

Toyota pointed to the Prius as proof of its commitment to the environment. This 2001 advertisement highlighted the company’s efforts to refine its hybrid system in a continued “search for even greener forms of transportation.” THF205087

Additional Readings:

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

- 1903 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Runabout

- Noyes Piano Box Buggy, about 1910: A Ride of Your Own

- Texaco "Fire-Chief" Gasoline Pump, circa 1940

environmentalism, hybrid cars, alternative fuel vehicles, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, cars

Hybrid Cars: An Old Idea Comes of Age

Built 86 years apart, two vehicles in The Henry Ford’s collection say a great deal about changing technology -- but they say even more about our society's changing values.

1916 Woods Dual-Power Hybrid Coupe

The Woods Motor Vehicle Company, established in 1899 as one of America's earliest automobile producers, was one of the biggest makers of battery-powered electric cars. But, by the early 1910s, the popularity of electric cars was waning. Gasoline-powered cars went farther on a tank of gas than electric cars went on a single battery charge, and filling an empty tank was easier and quicker than recharging batteries. These key shortcomings became more important as car owners drove their cars longer and longer distances. The Woods company sought to meet the challenge by building a car with two power-plants -- a clean, quiet, electric motor fed by batteries and an internal combustion engine fed by gasoline. The Woods Dual-Power automobile appeared in 1916.

Driving a Dual-Power was different from driving an electric or gasoline car. The driver manipulated levers to vary the balance between the gasoline and electric motors. THF103732

Driving a Dual-Power was considerably different from driving either an electric or a gasoline car. The driver began by moving a lever on the steering wheel to get the car rolling under electric power. When the car reached the speed of 20 miles per hour, the driver moved another lever to engage a clutch connecting the electric motor to the gasoline motor, starting the gasoline motor. By manipulating the levers, the driver varied the balance between the gasoline and electric motors; the car could run on both power sources at the same time, or either independently.

But the Dual-Power seemed to solve problems customers didn't have in 1916. The 48 miles-per-gallon figure claimed for the car meant little to a driver who could afford the Woods' $2,650 price. And the Woods' 35 miles-per-hour top speed was no better than a $740 Model T Ford sedan's. Woods didn't even advertise the Dual-Power's lower exhaust emissions, because automobile pollutants were of little concern at that time. It also seems that the Dual-Power was not as smooth and trouble free as the ads and brochures suggested. Woods re-engineered the car for 1917, but potential buyers were not impressed. The Dual-Power -- and the Woods Motor Vehicle Company itself -- vanished in 1918.

THF91040

2002 Toyota Prius Sedan

Ratchet forward to the 1990s. Automakers around the world were confronted by rising gasoline prices and stringent regulations on tailpipe emissions. Japanese giant Toyota set out to design a new car that dramatically improved gas mileage and dramatically reduced exhaust emissions. Toyota engineers probably never heard of the Woods Dual-Power, but in 1994 they settled on a dual-power design, combining a small gasoline engine with batteries and an electric motor. The first hybrid Toyota Prius went on sale in Japan in December 1997, and in the United States in August 2000.

Operating a Prius was simple -- a sophisticated computer system controlled both the electric and gasoline motors, smoothly shifting power between the two. THF91042

Although the Prius drivetrain was similar in principle to the Dual-Power's, operating a Prius was much simpler. The driver merely turned the ignition key, pulled the transmission selector lever into "D," stepped on the gas, and drove away. A sophisticated computer system controlled both the electric and gasoline motors, smoothly shifting power between the two. Sometimes the computer system used the gasoline engine to recharge the batteries. It even shut the engine off when the car stopped and started it up again as needed. The Woods engineers would have given their eye teeth for such technology. Woods sales staff might have given their right arms for the Prius' popularity.

Toyota's Prius hybrid sold well in Japan and even better in the United States. By 2005, Prius accounted for nearly 10% of Toyota's American sales. Part of that popularity was due to Prius' reliability, good performance, and considerable amount of interior room for its size. Part was due to Prius' excellent gas mileage -- over 40 miles-per-gallon on the highway and over 50 mpg in stop-and-go traffic. But it could take several years for savings on gasoline to make up for the several thousand-dollar price difference between a Prius and a comparable, conventional Toyota Corolla -- even with federal tax subsidies for hybrid cars.

For many people, what a car doesn't do -- use lots of gasoline, emit lots of pollutants -- has become as important as what it does do. THF205087

What really sold many people on the Prius was environmental responsibility. Driving cars with lower emissions and higher gas mileage was The Right Thing To Do, whether it reduced out-of-pocket expenses or not. Furthermore, driving a Prius told the world that you were Doing The Right Thing. The Prius became hip, especially among intellectuals and celebrities. Movie stars took to arriving at the Academy Awards in Priuses rather than limousines to demonstrate their concern for the environment. Even after other car makers such as Ford, Honda, Saturn and Nissan added hybrids to their lineups, the Prius retained its cachet.

The stories of the Dual-Power and Prius tell us that the definition of what we want an automobile to do is always evolving. Yes, we want cars to take us where we want to go. And taking us there in high style, or high comfort, or at high speed is often still important. But, for many people, what a car doesn't do -- use lots of gasoline, emit lots of pollutants -- has become as important as what it does do.

Bob Casey is The Henry Ford’s former Curator of Transportation. A version of this post originally ran in March 2007 as part of our Pic of the Month series.

hybrid cars, Driving America, Henry Ford Museum, environmentalism, electricity, power, by Bob Casey, cars, alternative fuel vehicles

1916 Woods Dual-Power Coupe: Hybrid Before Hybrids Were Cool

In 1916, gasoline was cheap, and no one cared about tailpipe emissions. But this hybrid wasn’t about fuel prices or pollution. Woods Motor Vehicle Company built it to capture new customers. Sales of the company’s electric cars were falling as more people chose gasoline-burning cars. The Dual-Power supposedly combined the best of both, but customers disagreed. The car and the company disappeared in 1918.

This 1913 Woods Electric was much like other companies’ electric cars. Sales of all electrics—not just Woods—declined in the teens. THF103736

The 1916 Dual-Power’s gasoline engine and electric motor are under the hood, connected by a magnetic clutch. Its battery box is under the seat, toward the rear.” THF103732

Woods used surprisingly antiquated imagery in the logo for the Dual-Power. Perhaps the company was trying to assure potential buyers that its radical new car was as reliable as the familiar horse. THF103741

Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, cars, power, alternative fuel vehicles, hybrid cars