A More Colorful World

| Written by | Katherine White |

|---|---|

| Published | 6/10/2020 |

A More Colorful World

| Written by | Katherine White |

|---|---|

| Published | 6/10/2020 |

This vibrant dress was likely dyed using an early aniline purple dye. Dress, 1863-1870 (THF182481)

In 1856, British chemistry student William Henry Perkin made a groundbreaking discovery. Perkin’s professor, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, encouraged his students to solve real-world problems. High on the list for Hofmann (and chemists all over the world) was the need to create a synthetic version of quinine. The only effective treatment for the life-threatening malaria disease, quinine could only be found in the bark of the rare Cinchona tree. Just a teenager at the time, Perkin decided to tackle this problem in a makeshift laboratory in his parents’ attic while on Easter holiday. Perkin experimented with coal tar—a coal byproduct in which Professor Hofmann saw promise—and made his discovery. No, not the discovery of a synthetic quinine, but something altogether different and extraordinarily significant nonetheless.

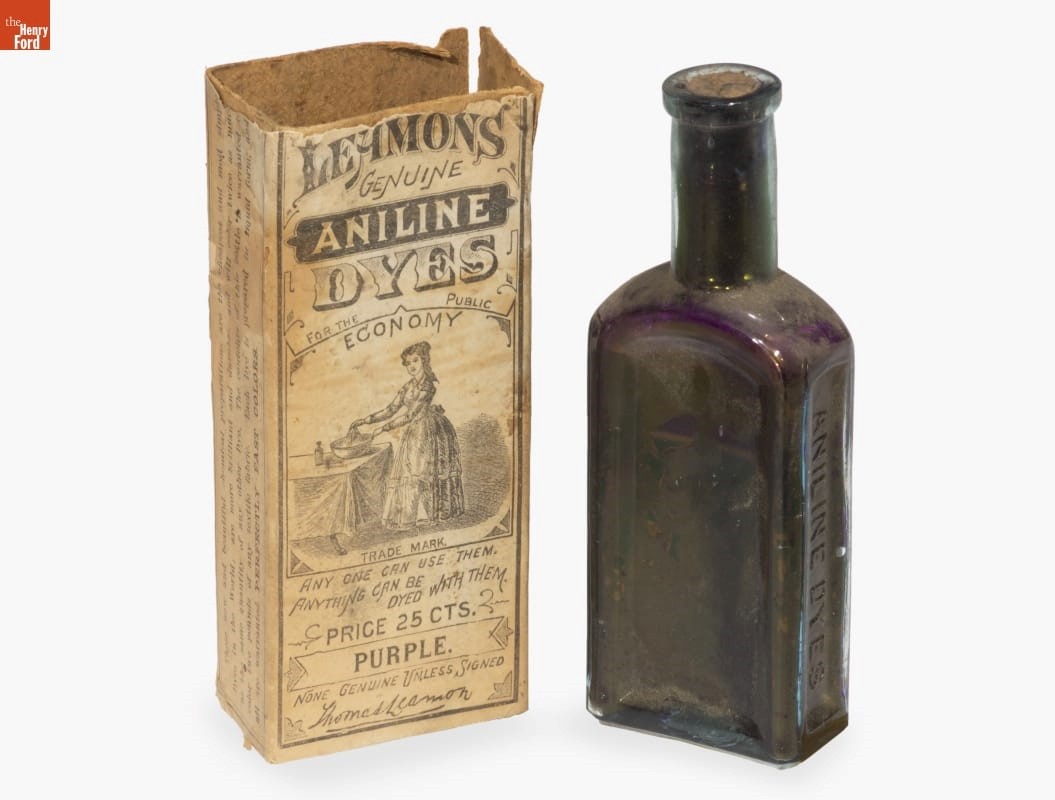

Wells, Richardson & Company "Leamon's Genuine Aniline Dyes: Purple," 1873-1880 (THF170208)

Perkin’s coal tar experiments resulted in a dark-colored sludge which dyed cloth a vibrant purple color. The purple dye was colorfast too (meaning it did not fade easily). He had discovered aniline purple—also known as mauveine or Perkin’s mauve—the first synthetic dye. Though this was not the medical miracle he had initially sought, he immediately understood the vast significance and marketability of a colorfast, synthetic dye.

Prior to Perkin’s discovery, natural dyes were used to color fabrics and inks and were derived primarily from plants, invertebrates, and minerals. Extracting natural dyes was time consuming and certain colors were rare. For example, arguably the most precious natural dye also happened to be a vibrant purple, called Tyrian Purple. This dye was found in the glands of several species of predatory sea snails. Each snail contained just a small amount of dye, so it took tens of thousands of sea snails to dye a garment a deep purple. Tyrian purple was so expensive that the very wealthy could afford to wear it. It’s no wonder purple was seen as the color of royalty!

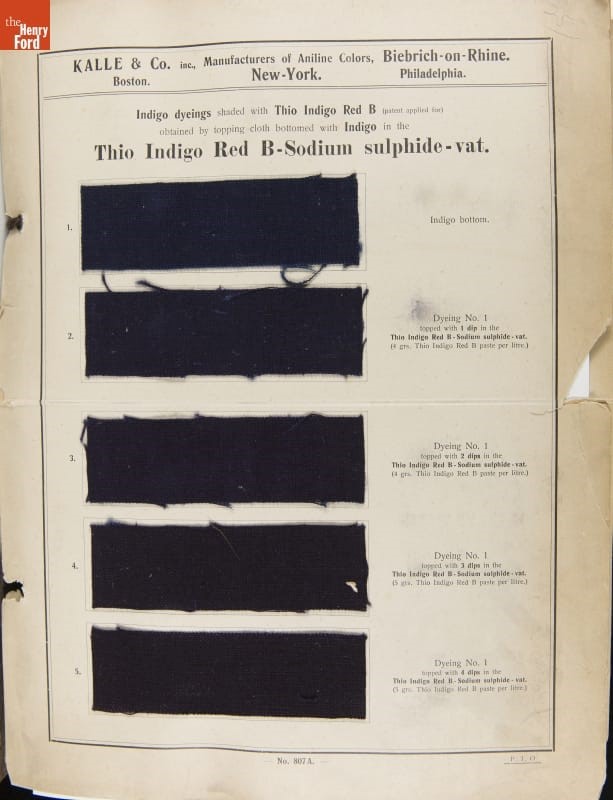

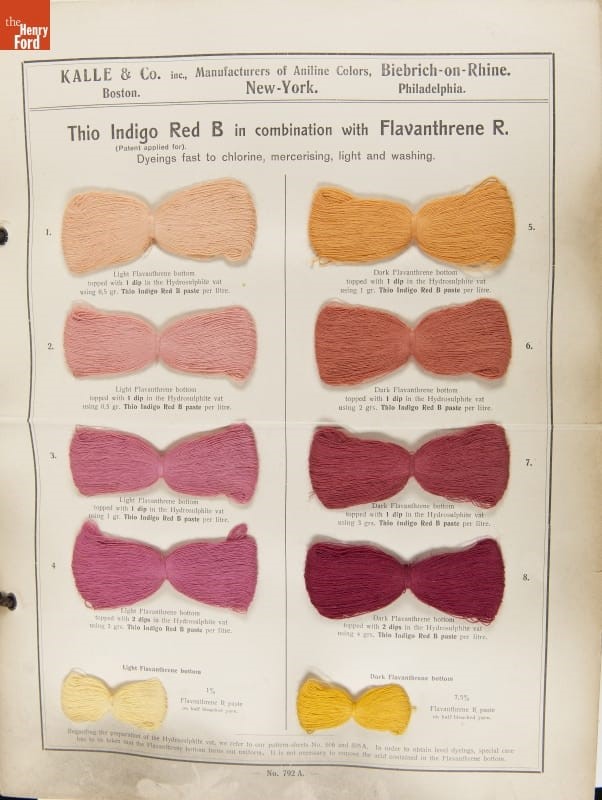

Fabric Dye Swatch Book, "Kalle & Co. Manufacturers of Aniline Colors," circa 1900 (THF286612 and THF286614)

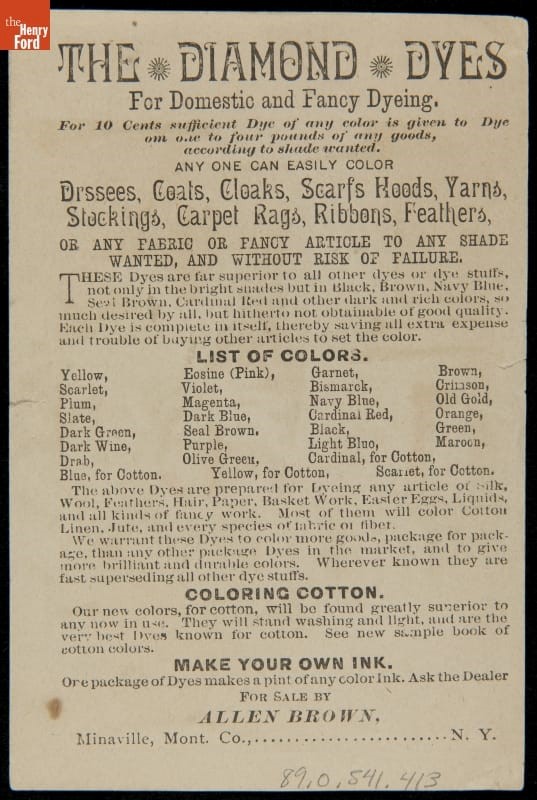

William Henry Perkin turned out to be multi-talented, finding success both as a chemist and as an entrepreneur. By 1857, with the help of his family, he began commercially manufacturing his aniline dye near London. He first produced purple, but other colors soon followed. The water in the nearby Grand Union Canal was said to have turned a different color each week depending on what dyes were being made. In 1862, Queen Victoria attended the Great London Exposition in a gown dyed with Perkin’s mauve and the color took off. Newspapers even reported a “mauve mania” in the 1860s! These new synthetic dyes were affordable too and other manufacturers around the world began to produce them. By 1880, companies like The Diamond Dye Company of Vermont sold many colors of dye—from magenta to gold or even “drab”—for just 10 cents apiece.

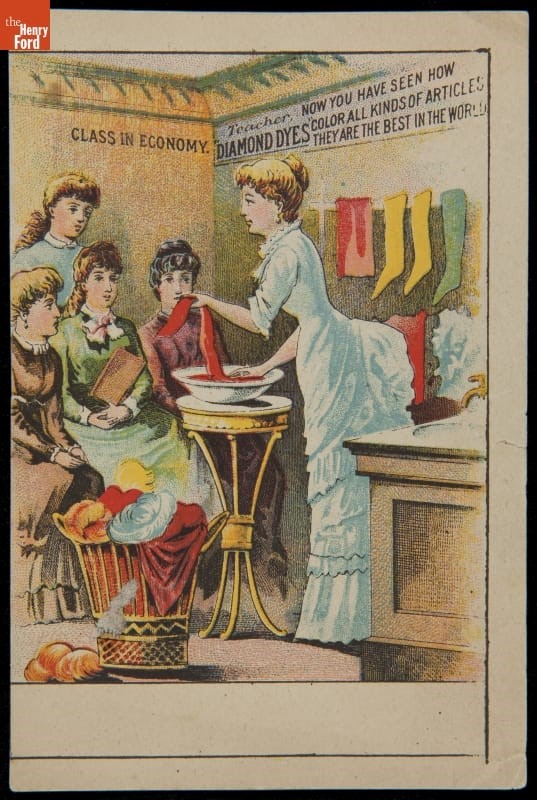

Trade Card for Diamond Dyes Company, 1880-1890 (THF214453 and THF214454)

Perkin’s discovery spawned an entirely new industry that transformed the world’s access to color. It is fitting that the very first synthetic dye created was purple—the color of Roman emperors and royalty could now be purchased for pennies. Louis Pasteur’s famous quote, “Chance favors the prepared mind,” characterizes Perkin’s serendipitous discovery well. His accidental discovery was far from simple luck – others may have dismissed it as a failed experiment. Instead, Perkin recognized the potential in his mistake and seized the opportunity to bring color to the masses.

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Themes |