Art Education: Louis Prang's Christmas Card Competitions

| Written by | Andy Stupperich |

|---|---|

| Published | 1/29/2026 |

Art Education: Louis Prang's Christmas Card Competitions

| Written by | Andy Stupperich |

|---|---|

| Published | 1/29/2026 |

The modern-day commercial Christmas card traces its origins back to England in the early 1840s when Henry Cole distributed holiday greetings on a card designed by John Callcott Horsley. The first American Christmas card appeared several years later. The innovative idea grew slowly in America until Louis Prang (1824-1909), a Boston-based German immigrant printer, educator, and colorist renowned for his chromolithographed artist prints, began creating small Christmas cards for the American market in the mid-1870s. His colorful holiday greetings were not much more than an extension of his business and trade card production. Prang's first cards featured an image of flowers with a brief holiday message—not the typical Christmas imagery found on cards today. Still, it was a successful enterprise. By 1880, Prang was selling nearly five million holiday cards a year—some now assuming more distinctive holiday themes. Also in 1880, he initiated a series of artist-designed Christmas card contests that attracted the public's attention and helped secure an annual holiday card-giving tradition. For these efforts, many consider Prang the father of the American Christmas card.

An early Prang Christmas card, 1877. / THF728302

An early Prang Christmas card, 1877. / THF728302

Prang's Christmas Card Competitions

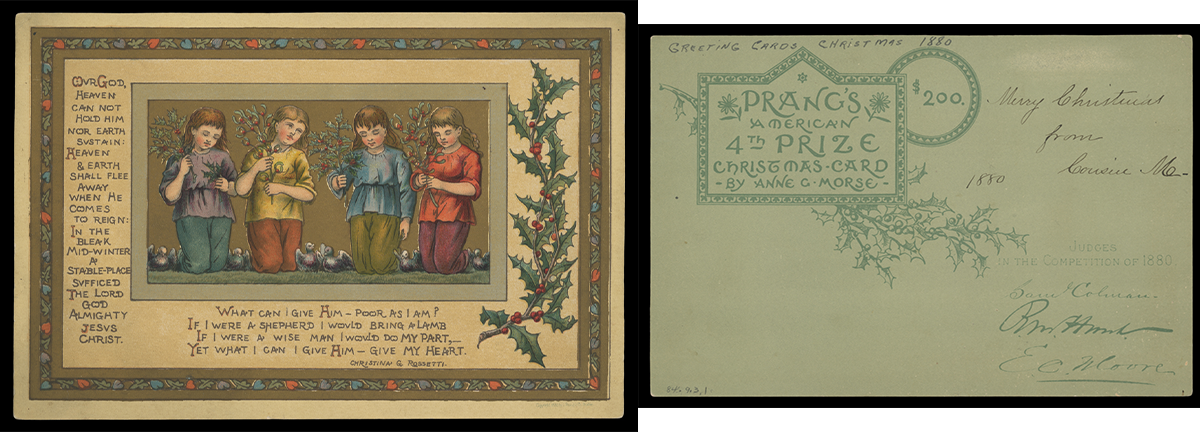

Louis Prang aspired to educate Americans about art through his chromolithographs, and his production of Christmas cards provided a unique opportunity to continue that passion. In the spring of 1880, Prang arranged an art contest for holiday card designs. He gathered several notable designers, architects, and artists to judge the competition. The cards would be exhibited at the American Art Gallery in New York, and prize money, totaling $2,000 for the top four designs, would be awarded. There were more than 800 entries. Prang would receive the winning entries from which he produced Christmas cards. Winning artists received recognition with their names placed on the backs of the cards, along with their prize position and the amount of money won. Prang also reserved the right to purchase any other card design that met his approval for production.

Anne G. Morse's design won fourth prize in the 1880 card competition. / THF716793 and THF716794

Anne G. Morse's design won fourth prize in the 1880 card competition. / THF716793 and THF716794

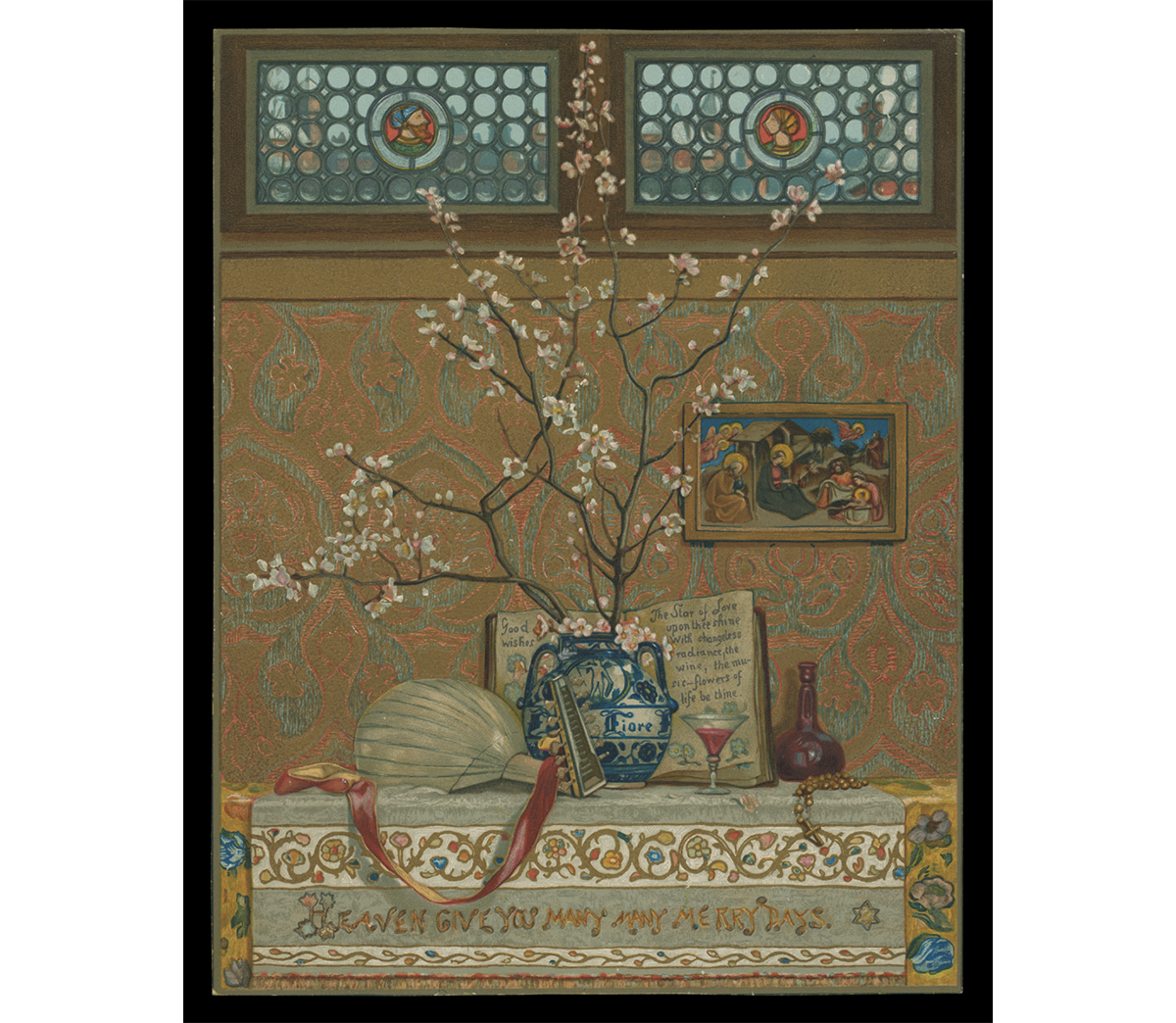

The public loved it. In February 1881, Prang held a second competition and exhibition. He again assembled a group of well-qualified judges, this time to assess nearly 1,500 entries.

Charles Caryl Coleman won third prize in the February 1881 competition. / THF716795

Charles Caryl Coleman won third prize in the February 1881 competition. / THF716795

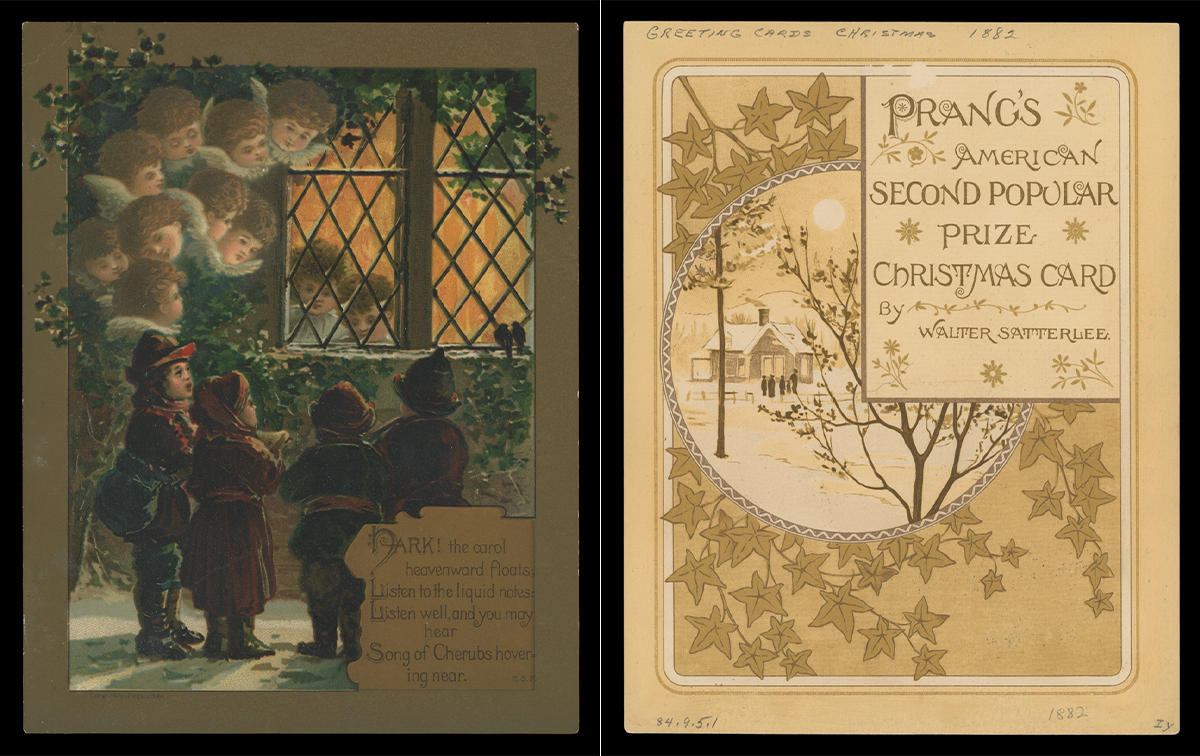

After this second showing, Prang conducted another round of card design competitions later in November 1881 (for 1882 production cards). Entries poured in. And the public flocked to the two exhibitions at New York's American Art Gallery. These showings piqued the public's interest even more because exhibition-goers now could vote for four popular prize award winners, alongside the jury awards. Art critics, however, questioned the quality of what they considered a flood of amateur works.

The fourth artist's prize for the November 1881 contest went to Alfred Fredericks. / THF716799

The fourth artist's prize for the November 1881 contest went to Alfred Fredericks. / THF716799

The November 1881 contest included popular prize awards. The exhibit going public gave the second popular prize to genre painter Walter Satterlee. / THF716797 and THF716798

The November 1881 contest included popular prize awards. The exhibit going public gave the second popular prize to genre painter Walter Satterlee. / THF716797 and THF716798

Prang decided to halt the contests after this competition. He had sparked the public's desire for art all too well, but the overwhelming number of amateur works held little value for Prang, artistically or monetarily. Also, design and literature competitions held by other companies (copying Prang's initial success) began to fail as professional artists and authors refused to submit their works to exhibitions awash with amateur entries. Prang would hold one last competition at the end of 1884, but limited the entrants to twenty-two selected artists. Judges would select four artist design winners—and only later would the public award one popular prize.

After the Competitions

Prang continued to produce Christmas cards after the run of competitions. But times were beginning to change. Other companies copied Prang's success, marketing their own fringed, tasseled, and colorful Christmas cards. Foreign printers also provided inexpensive alternatives, with some American producers contracting with German publishers to create colorful cards. With the flood of cards, Americans could now buy and send reasonably priced Christmas greetings to friends and family. Prang, however, still wanted his cards to meet his exacting standards, adding to the production time and cost. Consumer tastes also shifted. By the early 1890s, the large, frilly, high-priced cards—seen more as gifts than as greetings—began to fall out of favor in America. Prang, too, refocused and began to concentrate on other printing ventures, especially educational materials—a passion he had since his early years as a printer. The aging chromolithographer, credited as being the father of the American Christmas card, had, for all intents and purposes, left the holiday card market.

Andy Stupperich is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Themes |

|---|