George Balanchine and Ballet in America

| Written by | Rachel Yerke-Osgood |

|---|---|

| Published | 9/9/2025 |

George Balanchine and Ballet in America

| Written by | Rachel Yerke-Osgood |

|---|---|

| Published | 9/9/2025 |

If you are a fan of American ballet — be it regularly attending productions, seeing The Nutcracker at Christmas, or simply imagining what it would be like to be a prima ballerina — then you have likely engaged with the legacy of one of the dance world’s most important figures: George Balanchine.

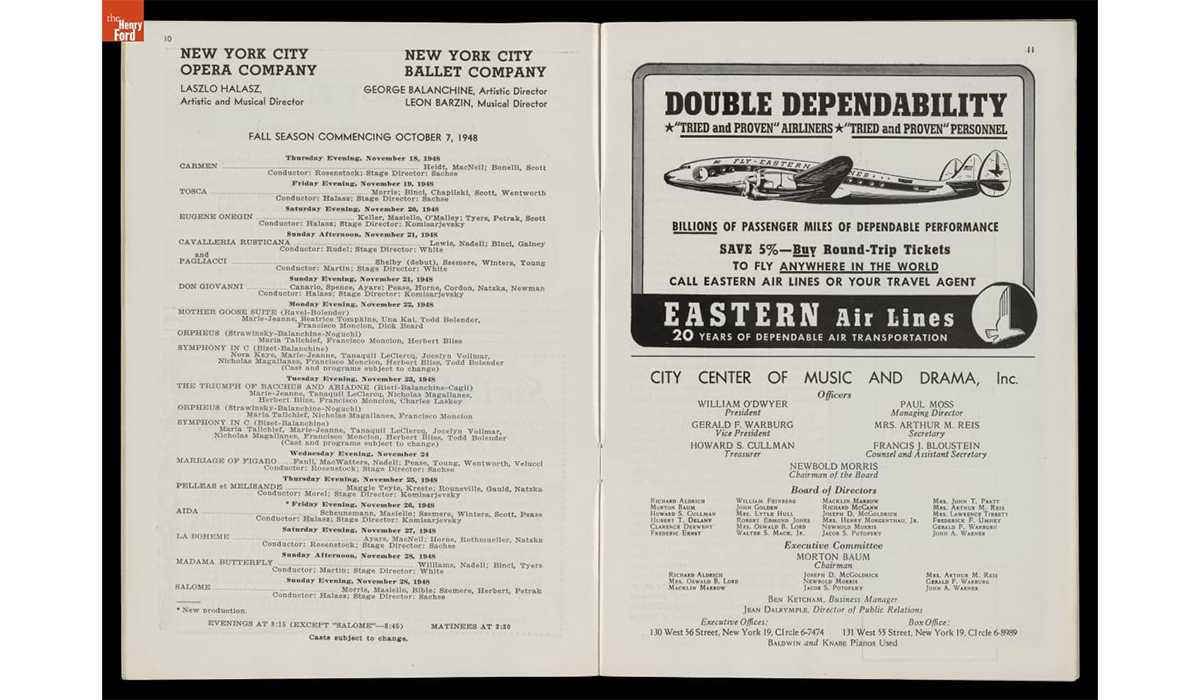

Program from New York City Center of Music and Drama, November 1948, featuring New York City Ballet’s schedule of Balanchine-choreographed performances / THF715566

Program from New York City Center of Music and Drama, November 1948, featuring New York City Ballet’s schedule of Balanchine-choreographed performances / THF715566

George Balanchine was born Georgiy Melitonovich Balanchivadze on January 22, 1904, in St. Petersburg, Russia. "He was exposed to the arts from birth, as his father was as his father was Meliton Balanchivadze, Georgian opera singer, composer, and founder of the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre. His Russian mother, Maria, was also a lover of ballet, and although she thought her son would eventually join the military, she insisted that he audition for dance. At age nine, Balanchivadze was accepted into the Imperial Ballet School at the Mariinsky Theatre. Throughout his early years at the school, Balanchivadze already started to work on his choreography. In 1920 he debuted his first piece — a duet, La Nuit, which was met with some disapproval from his school's directors.

When Balanchine was born, ballet was seen as a way of rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg society. The city was the cultural center of Russia, and remained so throughout World War I (when it was renamed Petrograd) and after the October Revolution (when it was renamed Leningrad). / THF208535

When Balanchine was born, ballet was seen as a way of rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg society. The city was the cultural center of Russia, and remained so throughout World War I (when it was renamed Petrograd) and after the October Revolution (when it was renamed Leningrad). / THF208535

After graduating, Balanchivadze enrolled at the Petrograd Conservatory, and worked at the State Academic Theatre for Opera and Ballet in their corps de ballet, before forming his own ensemble, the Young Ballet. The Soviet government granted permission for the group to travel around Europe, and they eventually settled in Paris. In 1924, Balanchivadze was invited to join the famous Ballets Russes as the main choreographer, quickly being promoted to ballet master of the company. It was here that he changed his last name to Balanchine, and shifted his focus exclusively to choreography after a knee injury.

After the bankruptcy of Ballets Russes in 1929, Balanchine found work with other European companies, and continued creating new pieces. In 1933, American writer and cultural figure Lincoln Kirstein convinced Balanchine to move to New York City. With Kirstein’s support, Balanchine founded the School of American Ballet, opening its doors in 1934 with the aim of providing more rigorous training for American dancers. In 1948, Balanchine and Kirstein founded the New York City Ballet. It was for this company that Balanchine would create perhaps his best-known work - his version of The Nutcracker.

When Balanchine first created his version of The Nutcracker, he returned to the stage in the role of Herr Drosselmeyer. / THF360453

When Balanchine first created his version of The Nutcracker, he returned to the stage in the role of Herr Drosselmeyer. / THF360453

Although it was not the first version of The Nutcracker to be performed in America - that distinction goes to Willam Christensen's 1944 staging for the San Francisco Ballet — Balanchine's 1954 production helped cement the ballet's popularity, and indirectly ensured the survival of ballet in America. His version is distinct from others in that “Clara” is called “Marie” (her name in E.T.A. Hoffman's original story) and it maintains the tradition of casting children for the roles of Marie and Drosselmeyer's nephew (who is also The Nutcracker that becomes the Prince), rather than casting adult principal dancers as became common in other productions. Today, annual performances of The Nutcracker are what keep many American ballet companies afloat, with ticket sales for performances constituting approximately forty percent of their yearly revenue; it is Balanchine's version that remains the most popular staging.

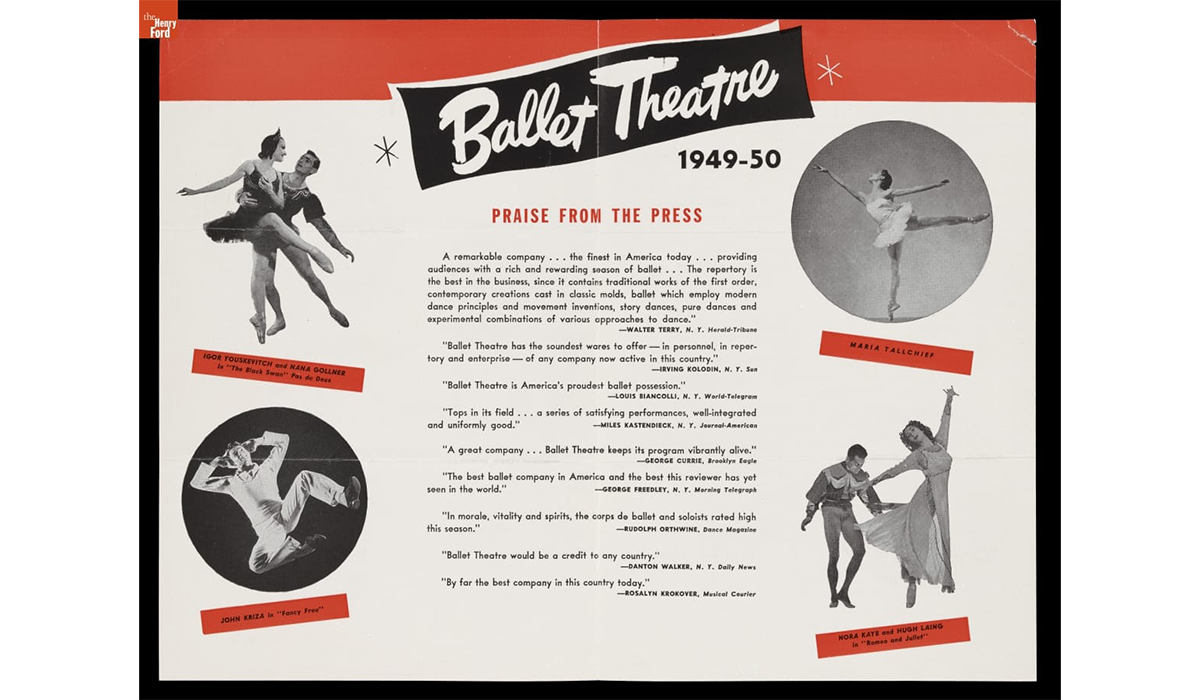

Famed dancer Maria Tallchief — the first major American prima ballerina, and a member of the Osage nation — was lauded for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker. She is often credited alongside Balanchine with revolutionizing American ballet. / Seen here at top right, THF715558

Famed dancer Maria Tallchief — the first major American prima ballerina, and a member of the Osage nation — was lauded for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker. She is often credited alongside Balanchine with revolutionizing American ballet. / Seen here at top right, THF715558

During his career, Balanchine founded several ballet schools, companies, and nonprofits. They include the previously mentioned School of American Ballet (1934-present) and New York City Ballet (1948-present), the American Ballet (1934-1938) which later joined with the American Ballet Caravan (1936-1941), and the Ballet Society (1946-present). Balanchine also served as the principal choreographer for Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo from 1944 to 1946.

In 1964, the Ford Foundation gifted almost $8 million to support professional ballet in America; nearly all of it went to Balanchine-affiliated companies. His choreographic work was prolific, as he created 400 individual works, many of which remain in the canon of ballet companies in America and abroad. He was also known for his choreography for Broadway and Hollywood productions, and for collaborating with the likes of composer Igor Stravinsky and designer Isamu Noguchi (who would continue working in the dance world by partnering with Martha Graham) for his productions.

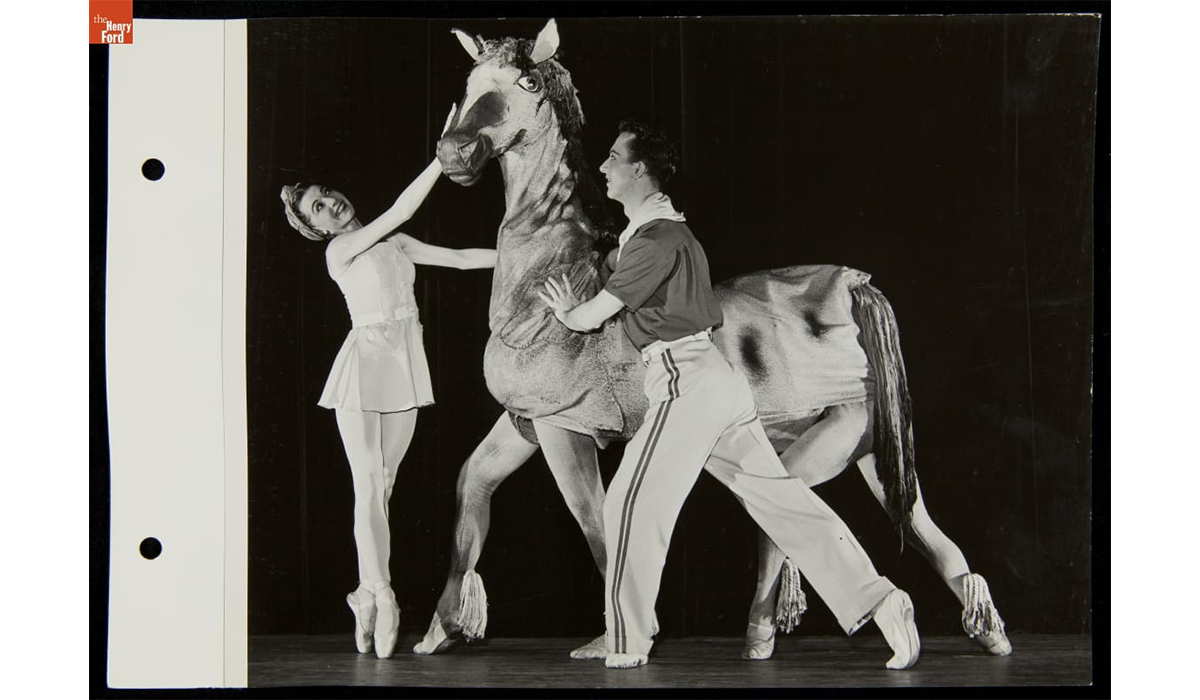

For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, Ford Motor Company hired American Ballet Caravan to perform A Thousand Times Neigh, a ballet telling the story of the automobile through the eyes of Dobbin the horse. The dancers had been trained at Balanchine’s American Ballet. /THF215723

For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, Ford Motor Company hired American Ballet Caravan to perform A Thousand Times Neigh, a ballet telling the story of the automobile through the eyes of Dobbin the horse. The dancers had been trained at Balanchine’s American Ballet. /THF215723

Balanchine’s impact on ballet in America is almost impossible to overstate. Writing for the New York Times after his death on April 30, 1983, Anna Kisselgoff called George Balanchine “one of the greatest choreographers in the history of ballet ... [who] established one of the foremost artistic enterprises the United States has called its own.” The Georgian immigrant became known as the father of American ballet, as his choice to move beyond the classical style of his original training created a distinctly American style, one that rejected classical models and instead embraced artistic expression and dance for its own artistic and athletic sake, rather than as just a storytelling medium. This focus on athleticism and aesthetics, though, did not come without cost. Through his prolific work, Balanchine’s ideal dancer — long-legged and extremely thin — became the standard for American ballet. The pressure for ballerinas to be almost preternaturally thin persists to this day, and eating disorders and body dysmorphia are sadly not uncommon.

The story of American ballet — for better and for worse — is in so many ways the story of George Balanchine.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Keywords |

|---|