Gone But Not Forgotten: Fisk Iron Coffins

| Written by | Rachel Yerke-Osgood |

|---|---|

| Published | 11/13/2025 |

Gone But Not Forgotten: Fisk Iron Coffins

| Written by | Rachel Yerke-Osgood |

|---|---|

| Published | 11/13/2025 |

In early 19th-century America, life was changing fast. More Americans were venturing farther from home as the country expanded westward and new innovations in steam and rail transport made travel more accessible. This also meant that more Americans were dying far from home. Society, though, still viewed it as important that a person be laid to rest among their family; to not have this final closure would have been deeply upsetting.

New York stove maker Almond Dunbar Fisk found himself in this very situation when his brother, William, died in Mississippi in 1844. Fisk’s family was unable to have William’s body returned to New York to be buried in the family plot, and the sorrow of the situation propelled Almond to look for solutions for families in similar situations. After applying his own knowledge of creating furnaces and boilers and consulting with experts in organic decomposition, in 1848 Fisk was granted a patent for an airtight cast iron coffin. With his father-in-law, Harvey Raymond, Fisk opened “Fisk and Raymond” in Manhattan and began selling his iron coffins.

Mummiform Iron Coffin, 1854-1858. This small coffin is unused and was possibly kept as a sales sample. / THF370110

Once thought to be only the privilege of the wealthy, more recent evidence and research suggest that iron coffins were relatively popular in the years before embalming became a common practice around the time of the Civil War. This makes sense when you consider how many practical issues the iron coffin addressed, beyond just body transport. Cholera was plaguing the nation, and the airtight seal of Fisk’s coffin design helped assuage fears of spreading the disease (as cholera is one of the incredibly few diseases that can be contagious even after death). Fisk and Raymond also advertised their coffins as a deterrent to grave robbery, although the fear of such acts was perhaps more prevalent than the act itself.

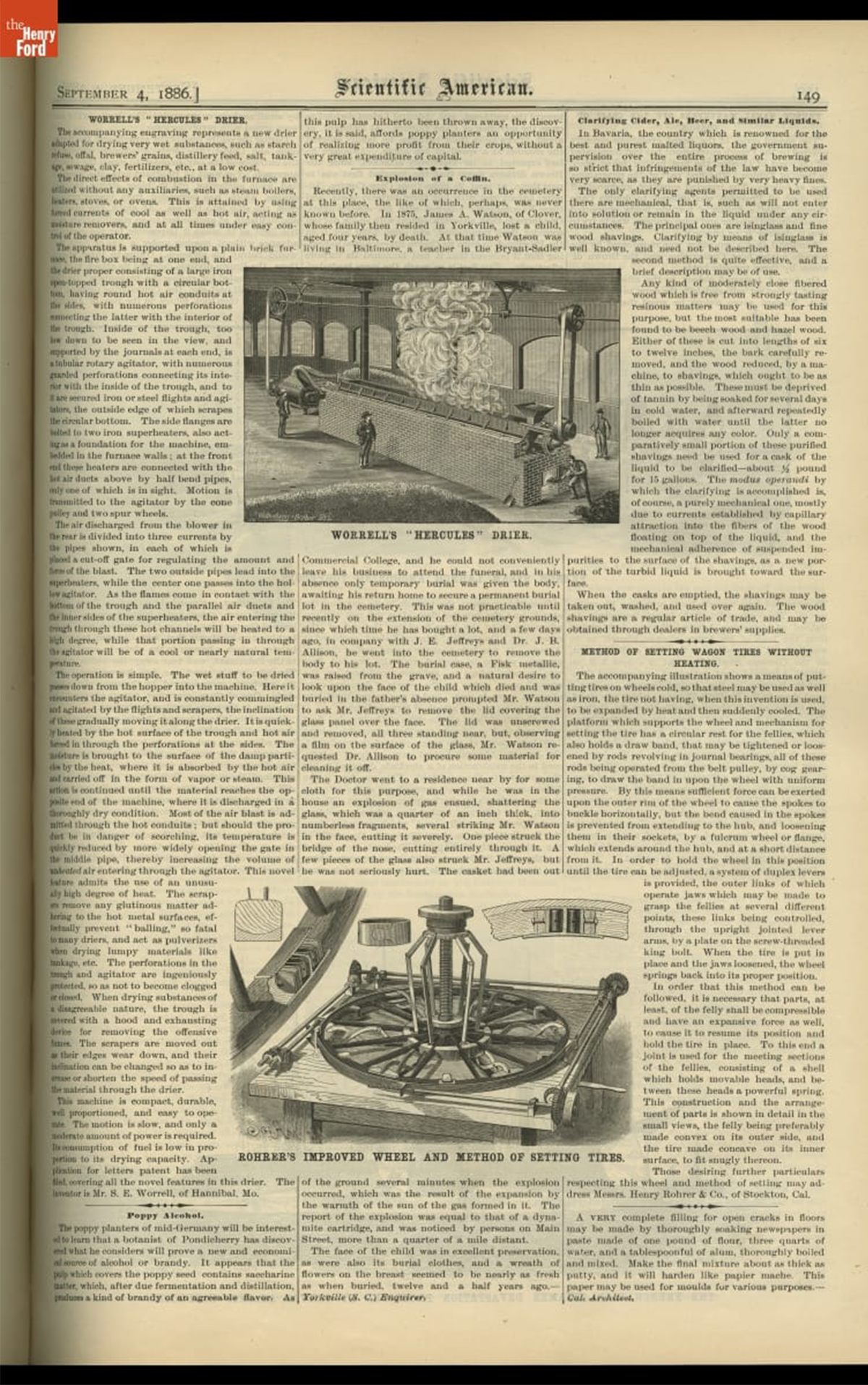

Iron coffins would be used or endorsed by several notable figures, including Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, James Monroe, Dolley Madison, John C. Calhoun, and Zachary Taylor. But they also received a bit of notoriety for another reason: anecdotes relating how they would occasionally “explode.” One such story in the September 4,1886, issue of Scientific American is fairly typical of the reporting of such stories: while waiting for family to return from out of town to arrange for a proper plot, a body was buried in a metal coffin in a temporary grave. When the final resting place was ready, the body and coffin were exhumed, and a family member asked to see their loved one’s face in the little glass window. The metal lid over the face was removed to reveal a glass viewing window, and the face was there—perfectly preserved. While the coffin was left briefly unattended before burial, “an explosion of gas ensued, shattering the glass . . . into numerous fragments . . . The report of the explosion was equal to that of a dynamite cartridge.” While it is in fact true that the buildup of gas inside the coffin could cause the glass to fracture and then break, particularly if there was a change in temperature, the strength of the “explosion” was often overstated for the sake of a more sensational story to tell.

Scientific American, Vol. 55, July-December 1886. The story of a Fisk coffin rupturing is found in the center column, under "Explosion of a Coffin.” / THF705631

While “Fisk coffins” or “Fisk burial cases” would become the shorthand for these iron coffins, Fisk and Raymond was not the only manufacturer. Through a combination of licensing the manufacturing rights, the patent changing hands, and changing company names, iron coffins were produced by companies including: W.C. Davis and Co.; Crane, Barnes and Co.; Crane, Breed and Company; W. M. Raymond and Company; and Metallic Burial Case Company. While production of these metallic coffins would cease around 1889, remaining stock continued to be sold until the start of the 1900s.

This “Fisk coffin,” produced by Crane, Breed and Company., maintains the mummiform shape of the original Fisk patent, but its decorative design is distinct to the manufacturer. The coffin mimics the folds of a burial shroud, and the rose at the foot is a common burial symbol, often used on headstones to convey various meanings. / THF370111

The Henry Ford is lucky enough to have one of these coffins in our collection—joining institutions such as the Memphis Museum of Science and History, Museum of Appalachia, the LSU Rural Life Museum, the Simpson Funeral Museum, and the Smithsonian. It provides a beautiful example of Fisk’s invention, and demonstrates the importance of keeping our loved ones close—even after death. Together with objects like our burial quilt, mourning jewelry, and items related to Dia de Muertos, our death-related collections paint a picture of the myriad ways grief, mourning, and remembrance manifest themselves. Macabre as these items may be to some, we need only dig a little deeper to see that they contain stories of great love and care.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

With gratitude to Scott Warnasch for sharing his detailed research.

Themes |

|---|