Kids on the Farm: A Year in the Life 1948

Lois and Robert Kelley craved outdoor space and projects to absorb their enthusiasm for life. After World War II they married and invested wholeheartedly in farming, believing it could provide peace of mind and sustenance for the family, with income supplemented by outside work. They bought an 11-acre property in Rockville, Connecticut, and modeled their work on the popular “Have-More” Plan promoted by Ed and Carolyn Robinson of Noroton, Connecticut.

The “Have-More” Plan motto, “A Little Land—A Lot of Living,” captured the farm family’s enthusiasm. At some point, Lois Kelley wrote Ed and Carolyn Robinson, explaining that “Your plan was the inspiration that led us to buy an 11-acre Homestead, complete with cow and chickens. . . . The fact that there is so little work is continually amazing to us, but perhaps it's because we really enjoy doing it. We're an enthusiastic advertisement for your plan.” The Robinsons must have cherished that letter because it appeared in a special issue of Mother Earth News (1, no. 2, 1970) devoted to the 1940s back-to-the-land plan.

Aerial view of the Kelley farm adapted to a Christmas card / THF720527

Aerial view of the Kelley farm adapted to a Christmas card / THF720527

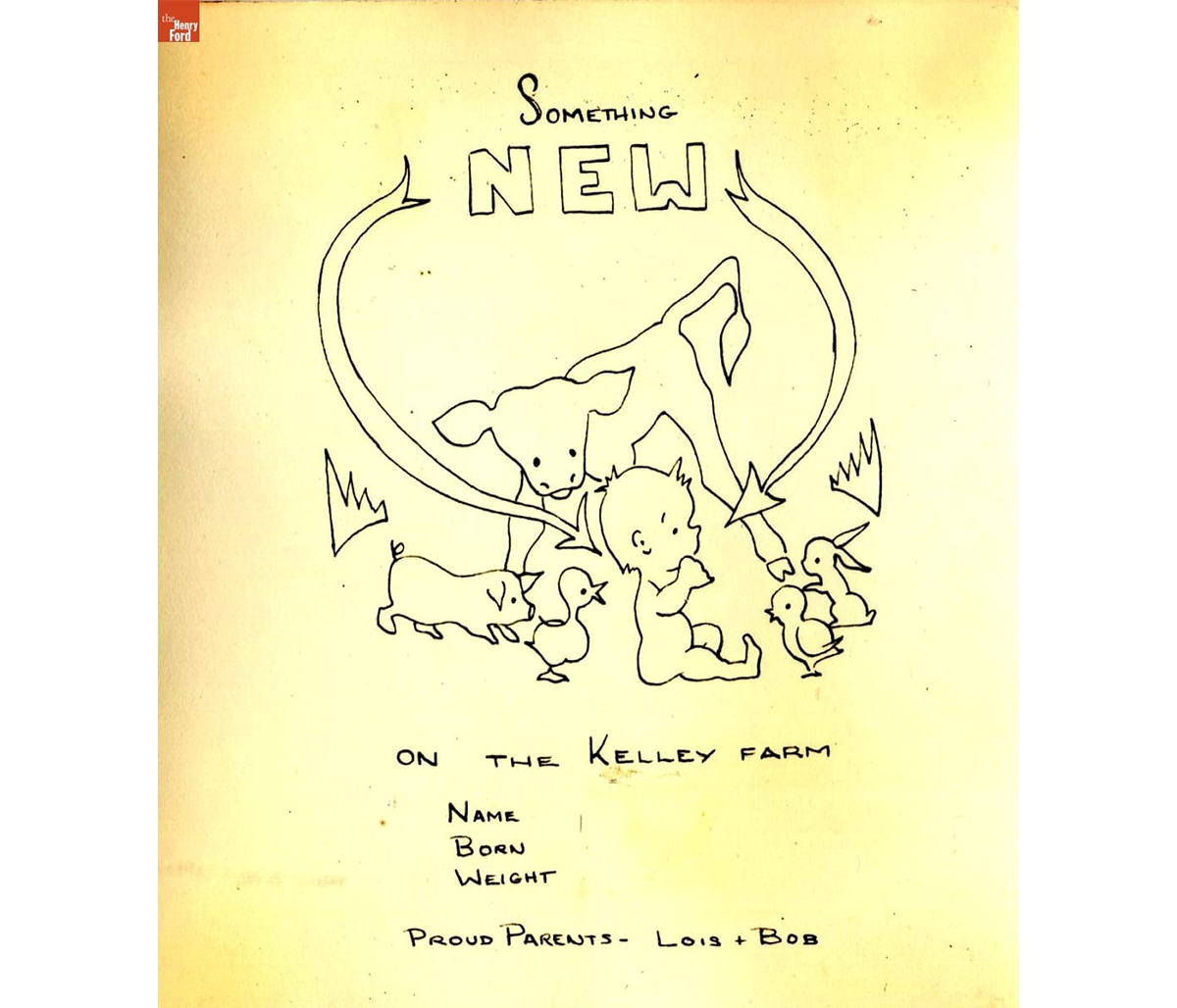

The Kelley farm included a house and barn, gardens, apple trees, hayfields, and berry patches, and after mid-1948, two children and dozens of farm animals. The birth announcement that Lois Kelley drew for Diane, her second child, shows the new baby with a calf, a piglet, a duckling, a bunny, and a chick. Lois rued the fact that, try as she might, she couldn't fit a goat kid into the picture.

D's birth announcement drawn by Lois Kelley 1948 / THF720614

D's birth announcement drawn by Lois Kelley 1948 / THF720614

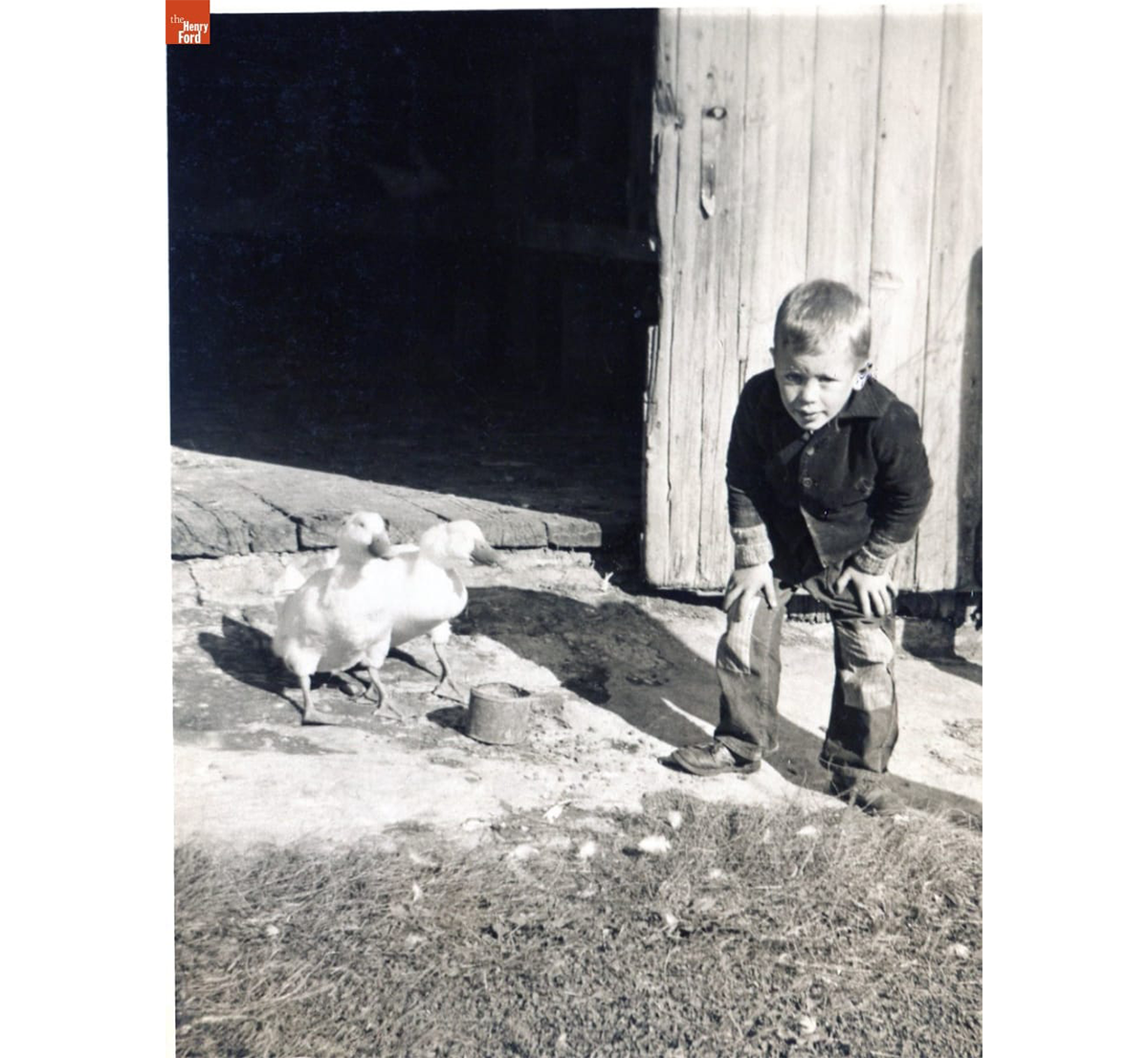

Diane and her brother Bobby grew up helping in the kitchen, barn, and garden. In a letter to her parents while she was pregnant with Diane, Lois wrote that her three-year-old son Bobby began doing chores. He fed the ducks and gathered eggs with her. The banty hens hid their nests in random places, to search out each morning as if it were Easter. A constant round of eggs incubated into ducklings, goslings, squab, and chicks in the cellar.

Bobby Kelley with ducks at the Kelley farm barn door, 1948 / THF720525

Bobby Kelley with ducks at the Kelley farm barn door, 1948 / THF720525

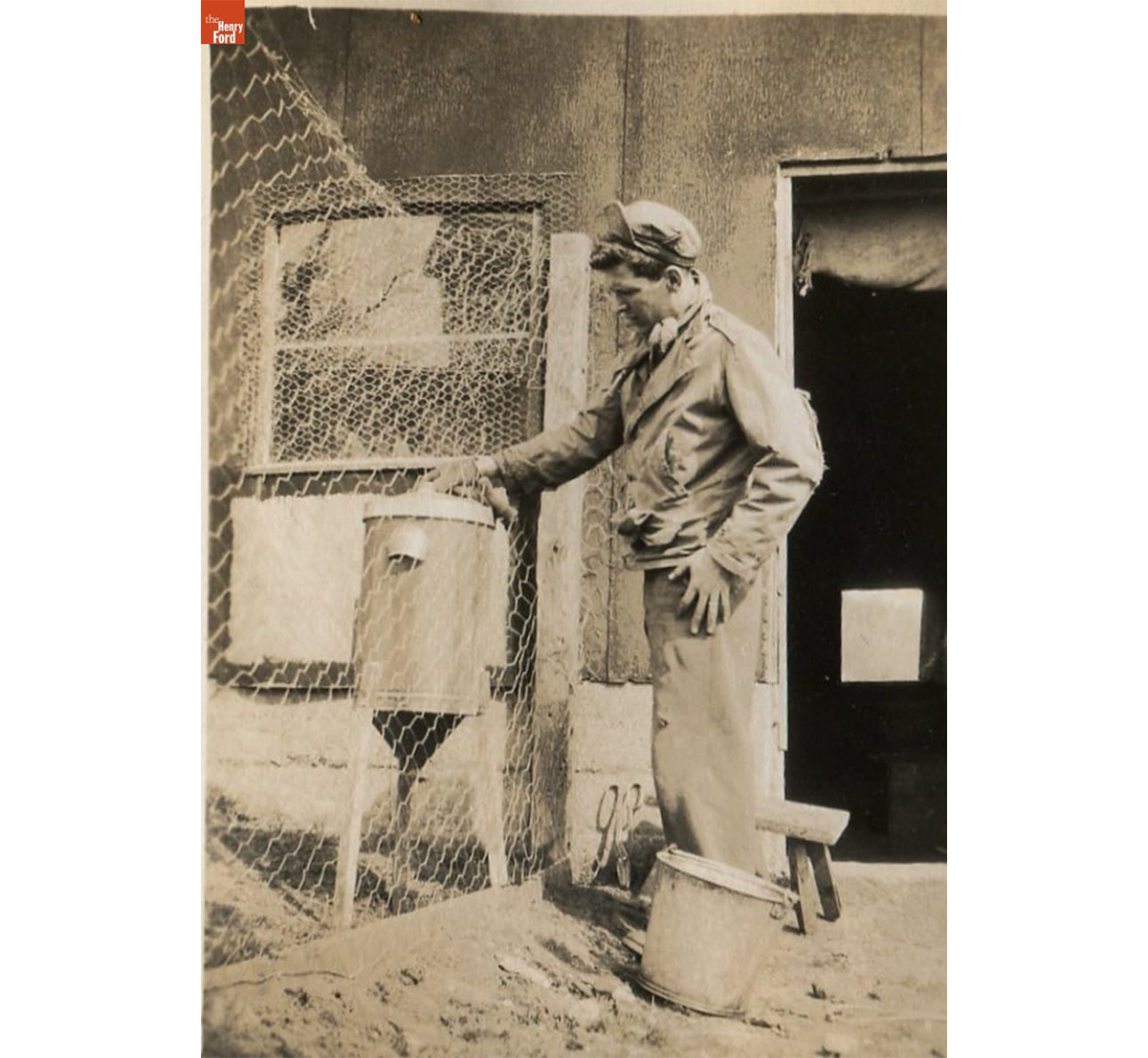

Each type of bird the Kelleys raised was hatched, fed, housed, and killed at the proper time, then prepared for the freezer or the table. Chickens, especially, fed the Kelley family all summer—broiled, fried, baked, or stewed. Lois wrote to her parents about a summer night when Bob surprised her by arriving home at midnight, bringing his sister and two of her children with him: “Lucky we'd planned on killing a chicken for Sunday dinner! The chicken killing was quite a process. The children watched . . . Bob tied its feet and hung it up instead of letting it flap all over, and later Judy, who's five, said to me, “You know, if Uncle Bob was going to cut my head off, he wouldn't have to tie my feet—I'd hold them still.”

New chicken coop at the Kelley farm with feeder (likely a repurposed cream separator), 1948 / THF720526

New chicken coop at the Kelley farm with feeder (likely a repurposed cream separator), 1948 / THF720526

The "Have-More" plan made clear that farm families raised livestock to meet their food needs. The Kelley family all pitched in to raise their food supply on their little farm. This included fresh dairy products that Lois poured over berries to make rich desserts that she gloated over, and fresh milk served with eggs and bacon at breakfast. Cow's milk helped fatten the calves and piglets that the family raised throughout the summer. The Kelleys also enriched the garden soil with the organic fertilizer that the livestock generated. This ensured the summer's bounty of vegetables and fruit. Then, in the fall the family had the grown steers and pigs butchered, and they wrapped the meat and stored it in the freezer.

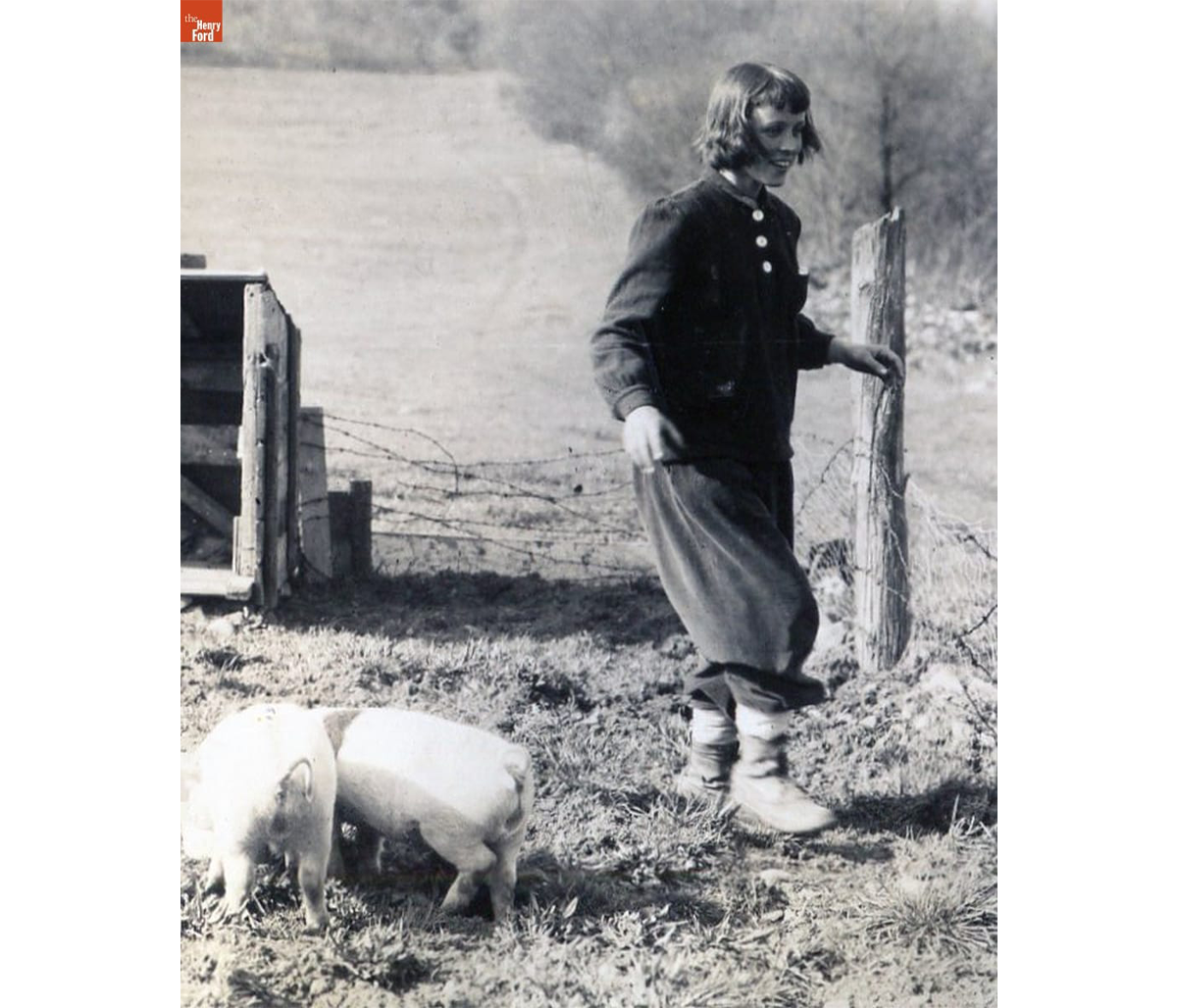

The process began with the arrival of piglets.

The Kelleys secured their first piglets in May 1948. Then, Lois wrote to her parents: “from Pig Heaven, May 3, 1948 . . . our biggest thrill is the pigs. They're well settled, little and white and cute—and one has a black spot and a blackish ear so we can tell them apart.” Bob built a pen with chicken wire and barbed wire, and a three-sided shelter of scrap wood. Lois was gratified that the piglets, though they previously had only nursed from their mother, knew exactly how to “eat like pigs.” She explained to her parents that “They began rooting like old-timers, and the battle they had over a pan of milk was something to see.” She hadn't expected that the pigs would inspire three-year-old Bobby to mimic them. “There he was,” Lois wrote, “on his hands and knees trying to root in the ground with his nose—his mouth full of dirt.”

Lois Kelley with the first piglets, 1948 / THF720528

Lois Kelley with the first piglets, 1948 / THF720528

Three weeks later, on May 24, Lois wrote that “The pigs seem to be at least twice the size they were ... Their hide is so tough by now that they don't respond to a good healthy slap, and if they had the least desire, they could be outside their pen in two minutes. . . . It was tough enough to catch them before, and now . . . it would be a job to keep hold.”

In June, barely a month after the piglets arrived, Lois's naivete over their cuteness was over. She explained in a letter to her parents that: “Yesterday the 'black 'pig got out once too often—he'll never do it again. Both nasty animals are now settled in the cellar of the barn where we said it was utter inhumanity to keep an animal. They brought it on themselves, however . . . They're getting awfully heavy to move .. It'll be a relief to the neighbors too, who have helped me catch this one on the several past occasions when it's rooted out.” On October 9, she wrote that feeding them had “become quite dangerous—not that they're ferocious, but they're so eager to be fed that they swing their weight around with a terrible disregard for any one else's rights. I've given up going in—just the noises they make behind that door are enough to terrify me.”

Kelley barn in a Snowstorm, 1948 / THF720523

Kelley barn in a Snowstorm, 1948 / THF720523

November 3rd six months from the day the “cute” piglets arrived, they met their fate as provisions for the freezer. Lois wrote that the butcher dispatched them with his .22, bled them, “then drove off with them in his truck to scald, scrape, disembowel and chill them at his place.”

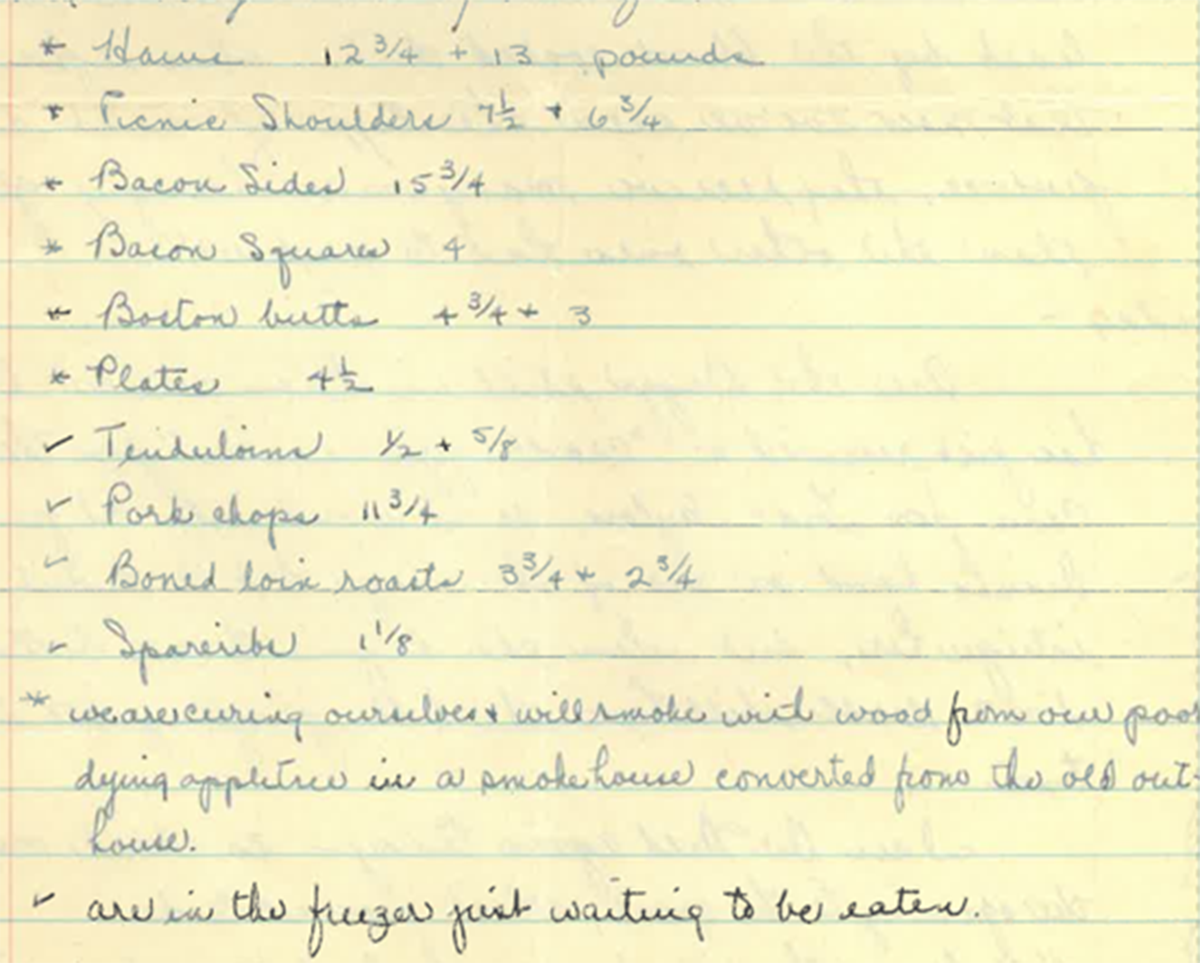

Lois and Bob cut and wrapped the meat from one of the pigs, weighing 154 pounds, and a neighbor took the other in trade for spring plowing. Together, they provided the following (plus sausage, head cheese and lard):

Detail from “Dear Mother and Dad” letter, November 3, 1948 p3. Image provided by Daisy Kelley.

Detail from “Dear Mother and Dad” letter, November 3, 1948 p3. Image provided by Daisy Kelley.

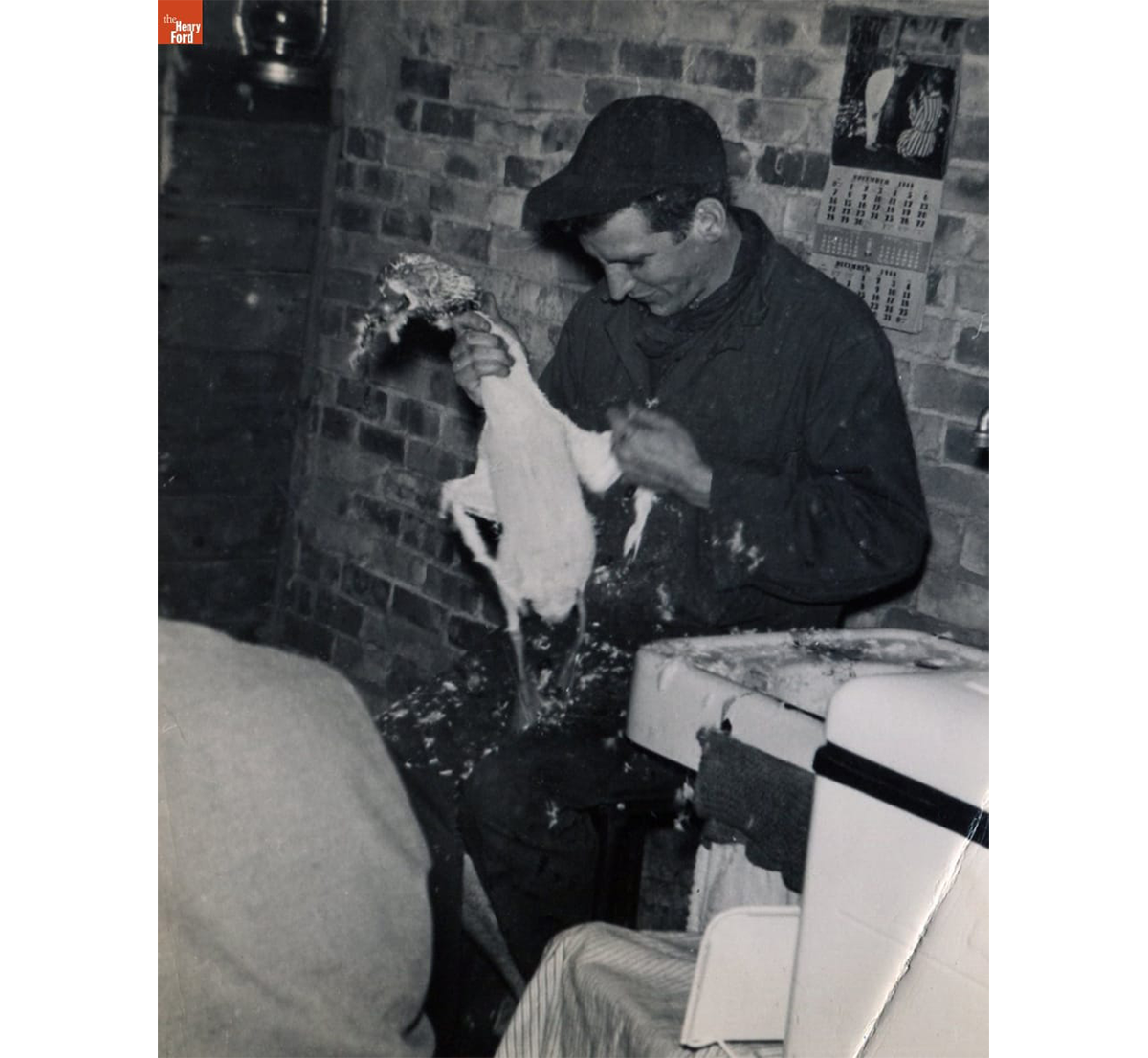

The Kelley family prized the food in the freezer year-round, but the larder took on special meaning for the holidays. In August Lois began dreaming of Thanksgiving dinner. Would she serve turkey, capon, duck, rabbit, or broiled or fried chicken? Corn on the cob, raspberry or strawberry shortcake, tons of vegetables, blueberries, squash, ice cream? Lois's letters tell that when the first Thanksgiving on the farm finally arrived, duck was served. They were the same ducks Bobby had fed daily as part of his chores. “We are proud,” Lois wrote, “that though Bobby took care of them from the time Bob brought them home, he was just as interested in the killing, plucking, and eating of them as the rest of us.”

Bob Kelley plucking a duck on the night before Thanksgiving, November 24, 1948 / THF720524

Bob Kelley plucking a duck on the night before Thanksgiving, November 24, 1948 / THF720524

On Christmas Day 1948, Lois and Bob took the first of the hams out of the freezer for dinner, a finale for that year’s pigs and for 1948, the family’s first year raising food on the farm.

This article was written by Diana “Daisy” Kelley, Curatorial Research Volunteer, The Henry Ford, with Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment, The Henry Ford. The stories and pictures are from the Lois Kelley collection at The Henry Ford.

You can read more about the Kelley family and their stewardship of a sugar bush on their second farm (another supplement to their food supply and their farm income) in the blog, "Maple Trees and Family: A Long-Term Relationship."

Facebook Comments