Making the Connection: Phoning on the Go

When telephones were first introduced in the late 1800s, people wanting a phone would subscribe to the local phone company’s services and receive a telephone on lease. Using the telephone at this time meant that both caller and receiver were tethered to their respective locations. But as American life became more bustling and more people found themselves away from home for greater portions of their day, telephone technology adapted.

Pay telephone featuring patents by William Gray, circa 1898 / THF805358

Pay telephone featuring patents by William Gray, circa 1898 / THF805358

In 1889, the first public, coin-operated pay telephone was installed in Hartford, Connecticut, at the Hartford Connecticut Trust Company. The device had been conceived of and patented by William Gray; according to legend, he was inspired by his inability to find a publicly available phone when his wife was ill and needed a doctor. The pay telephone worked by creating slots for different denominations of coins, and different chimes or bells would sound as the money was deposited. Once the right amount had been deposited—the operator could tell by the chimes—the call would be put through. The Gray Telephone Pay Station Company, founded by Gray in 1891, would go on to install pay telephones across the country and refine their designs, creating different models for different needs and locations, from city streets to hotel lobbies. The company would be incredibly successful, even surviving the Great Depression before being bought out by Automatic Electric in 1948.

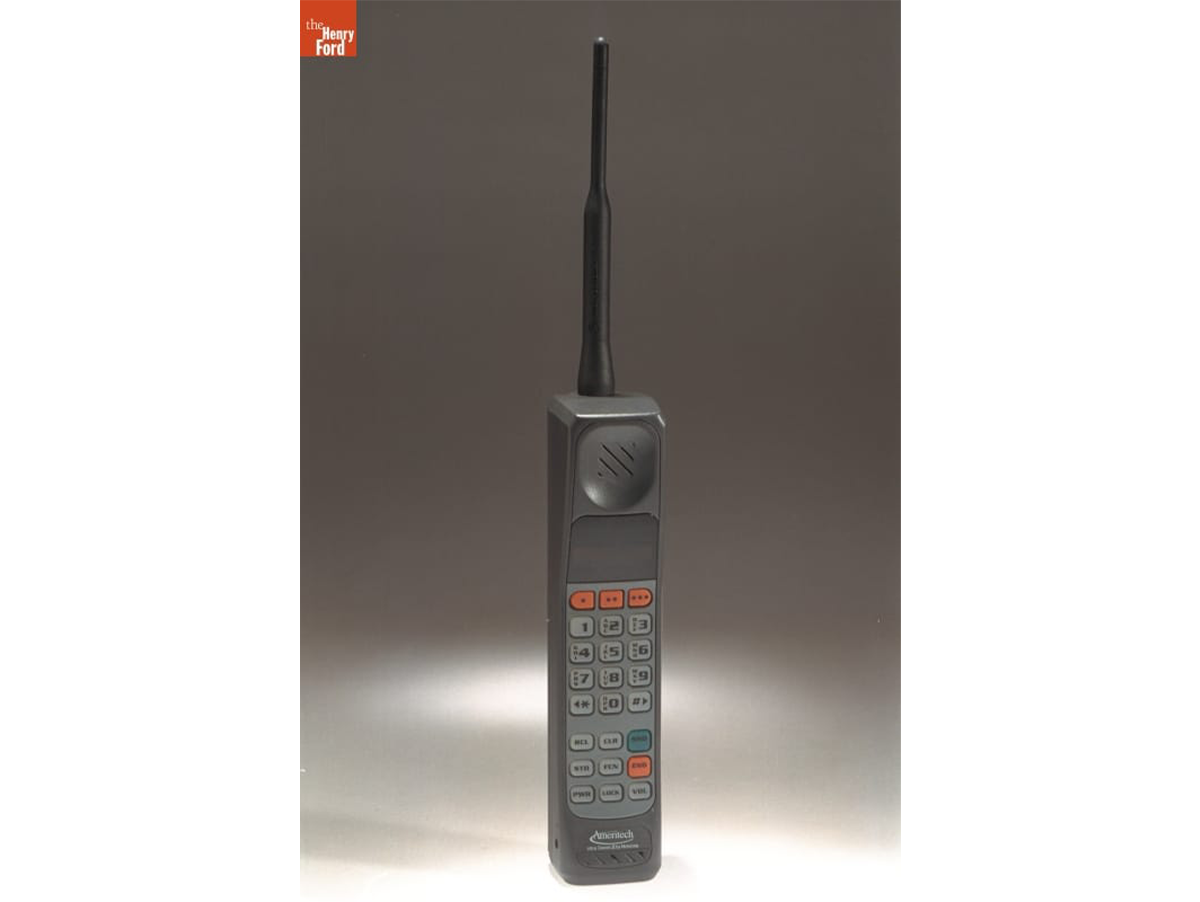

Motorola Brick Phone, 1985 / THF97588

Motorola Brick Phone, 1985 / THF97588

On April 3, 1973, Motorola engineer Martin Cooper made the first publicized cell phone call—to Joel Engel, who was working at AT&T trying to develop the same technology, which would allow users to make calls without having a physical connection to a network, unlike previous phones. While the car phone—a device that was mounted in the trunk of a car, with cables running through the vehicle to connect to a headset in the cabin—already existed and allowed for some mobile communication, its adoption was intentionally limited by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which required licenses for its use. Motorola continued refining their cellphone technology, and in 1983 they had the first commercially available cellphone ready for the market. By 1990, over one million Americans were using cellphones.

Pay phones and mobile phones help people get in touch on the go. But what about when the recipient, not necessarily the caller, is out and about? For that, we turned to different technologies—including the answering machine and the pager.

AT&T Model 2100 Telephone Answering Machine, circa 1983 / THF323526

AT&T Model 2100 Telephone Answering Machine, circa 1983 / THF323526

Although the first automatic answering machine was invented in 1935, the first commercially viable machine didn’t arrive until 1971, with PhoneMate’s Model 400. By the end of the 1980s, one in three American households owned an answering machine. While the concept may seem simple, the implications for telephone culture were immense. Now there was a way to be continuously available; even if you were away from your telephone, the machine would make sure that the caller’s message was there waiting for you when you returned. The adoption of answering machines also led to a change in the culture around phone calls. On the one hand, calls were easier to screen, but on the other, a missed call no longer meant the onus was on the caller to try again, but rather on the recipient to phone back.

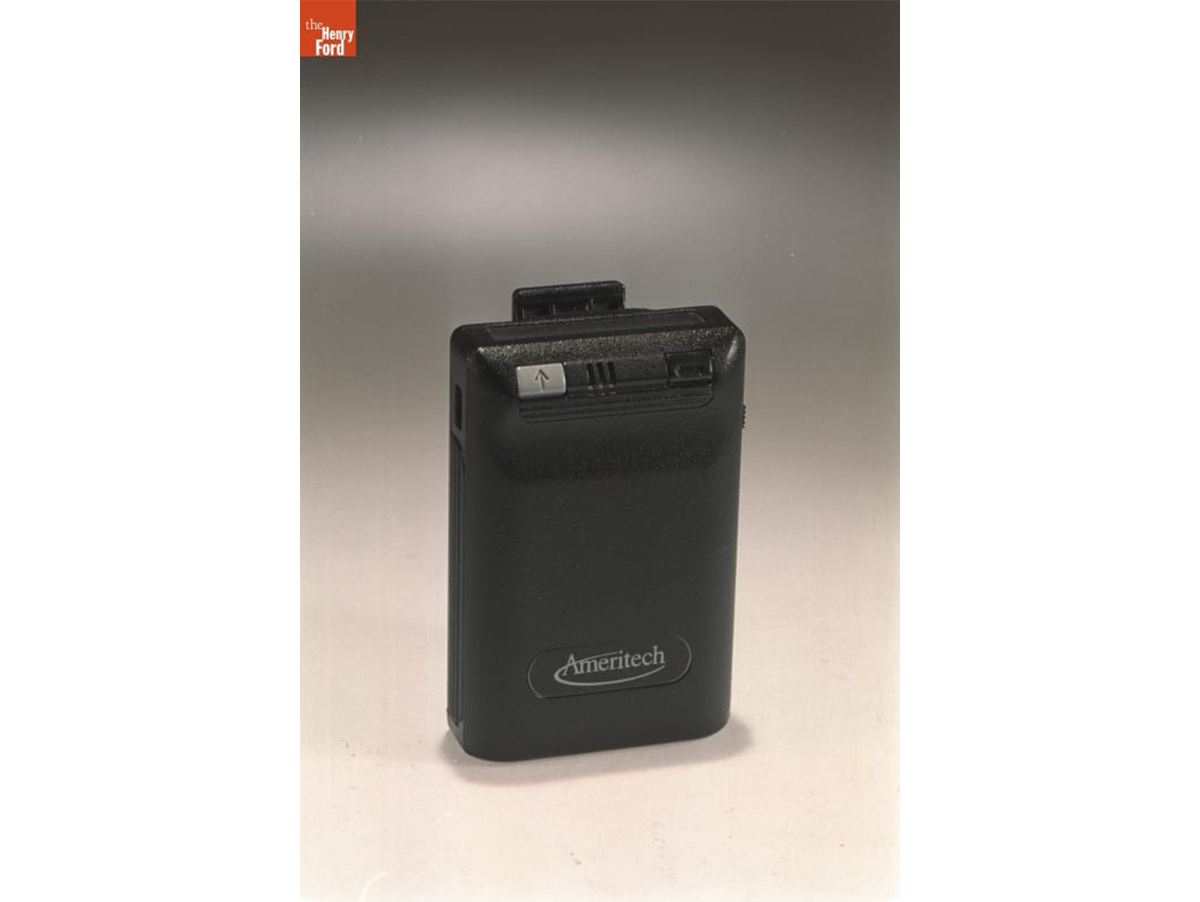

Motorola Pager, 1995 / THF302299

Motorola Pager, 1995 / THF302299

In 1949, wireless communication pioneer Al Gross patented the very first telephone paging device. The following year, the device was put into service at New York's Jewish Hospital—marking the start of what would be a long history of use in critical communications. In 1959, Motorola coined the term “pager,” and the name stuck; in 1964, they would become the main force in the pager market with the first versions available to consumers. While the first pagers delivered tone-only messages, by the 1980s new versions had been developed that displayed alpha-numeric messages, allowing people to send short messages without having to pick up a phone. By 1994, over 61 million pagers were in use. Although the rise of cell phones with the ability to send text messages led to pagers falling out of favor with the general public, pagers remain a crucial part of many hospitals' and first responders' communication systems.

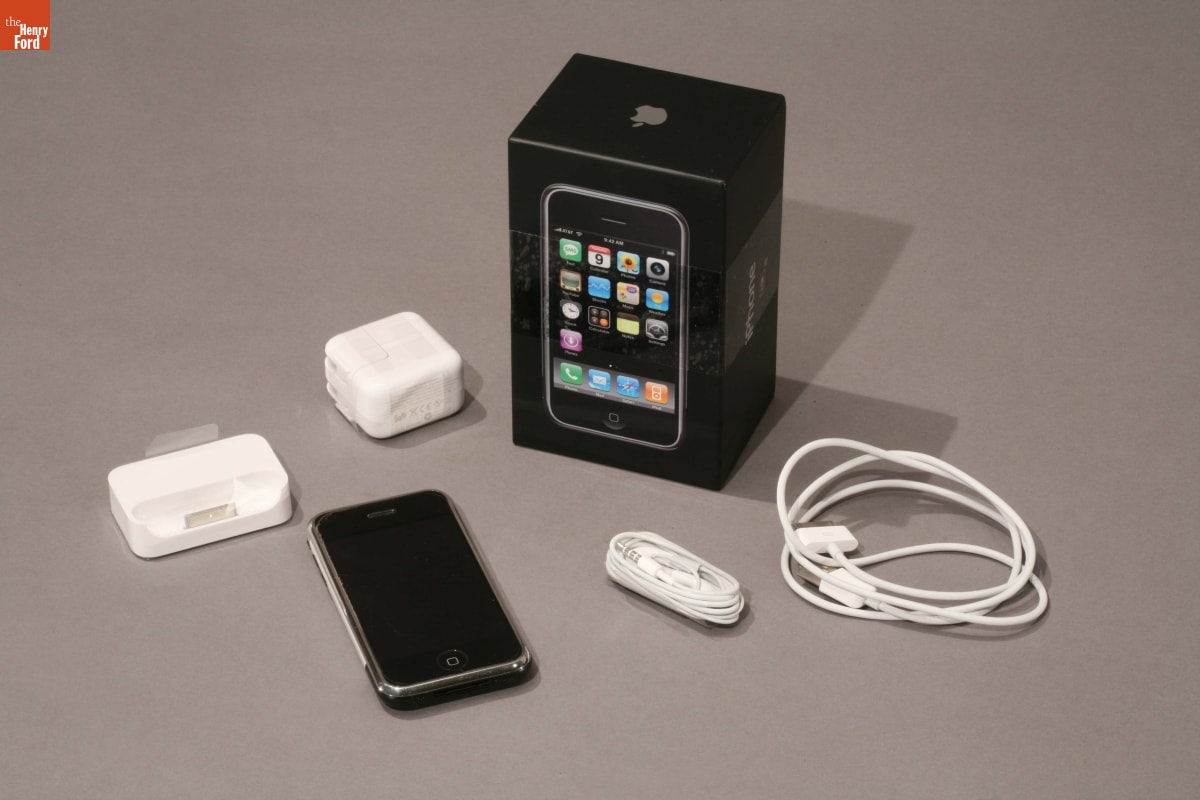

iPhone, 2007 / THF92290

iPhone, 2007 / THF92290

Of course, thanks to the smartphone, our telephone technology now solves more problems than ever before, all in a conveniently portable package. Landline telephones have waned in popularity, and for many of us, our mobile phone is now our only phone. We can text paragraphs of thoughts with a few swipes on a screen. Our phones not only automatically come with a voicemail function, but many of them will even transcribe the messages for us. We’re more reachable than ever before, yet many of us talk on the phone even less. The remnants of the technology that led to this moment still exist, though—just waiting for us to make the connection.

A functioning pay phone can still be found—and used!—in the Welcome Center at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by Rachel Yerke-Osgood

A functioning pay phone can still be found—and used!—in the Welcome Center at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by Rachel Yerke-Osgood

The Henry Ford's 1898 pay telephone was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Servcies (IMLS).

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Facebook Comments