Women and the American Red Cross: Evidence in The Henry Ford Collections

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 8/21/2025 |

Women and the American Red Cross: Evidence in The Henry Ford Collections

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 8/21/2025 |

The following article shares highlights from the collections of The Henry Ford to illustrate work undertaken by female Red Cross volunteers during World War II. More than three million women repaired and drove vehicles as part of the motor corps, cared for wounded service members in military hospitals, operated blood banks or operated canteens overseas, among numerous other tasks. The collections included here can help us to understand the role of women in the American Red Cross during wartime.

Join American Red Cross poster, 1942. / THF289755

The poster above conveys the centrality of women to the U.S. military response during World War II. The Red Cross, a non-governmental organization, “always stands by as friend to the service man” (Redlands [California] Daily Facts, 12 November 1941). The illustrator, Robert C. Kauffmann, emphasized the Red Cross nurse in other colorful posters during this time—aimed at recruiting nurses, field directors and hospital recreation workers. Sometimes he contextualized the nurses’ work in domestic flood relief, sometimes in war relief, but always with the message to “join.”

Women’s Motor Corps

Comparable service during World War I set a precedent. The American Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps began in 1917 and included women volunteers who transported the sick and wounded in ambulances.

Red Cross training using Ford Model T ambulances at the Highland Park Plant, July 1918. / THF130013

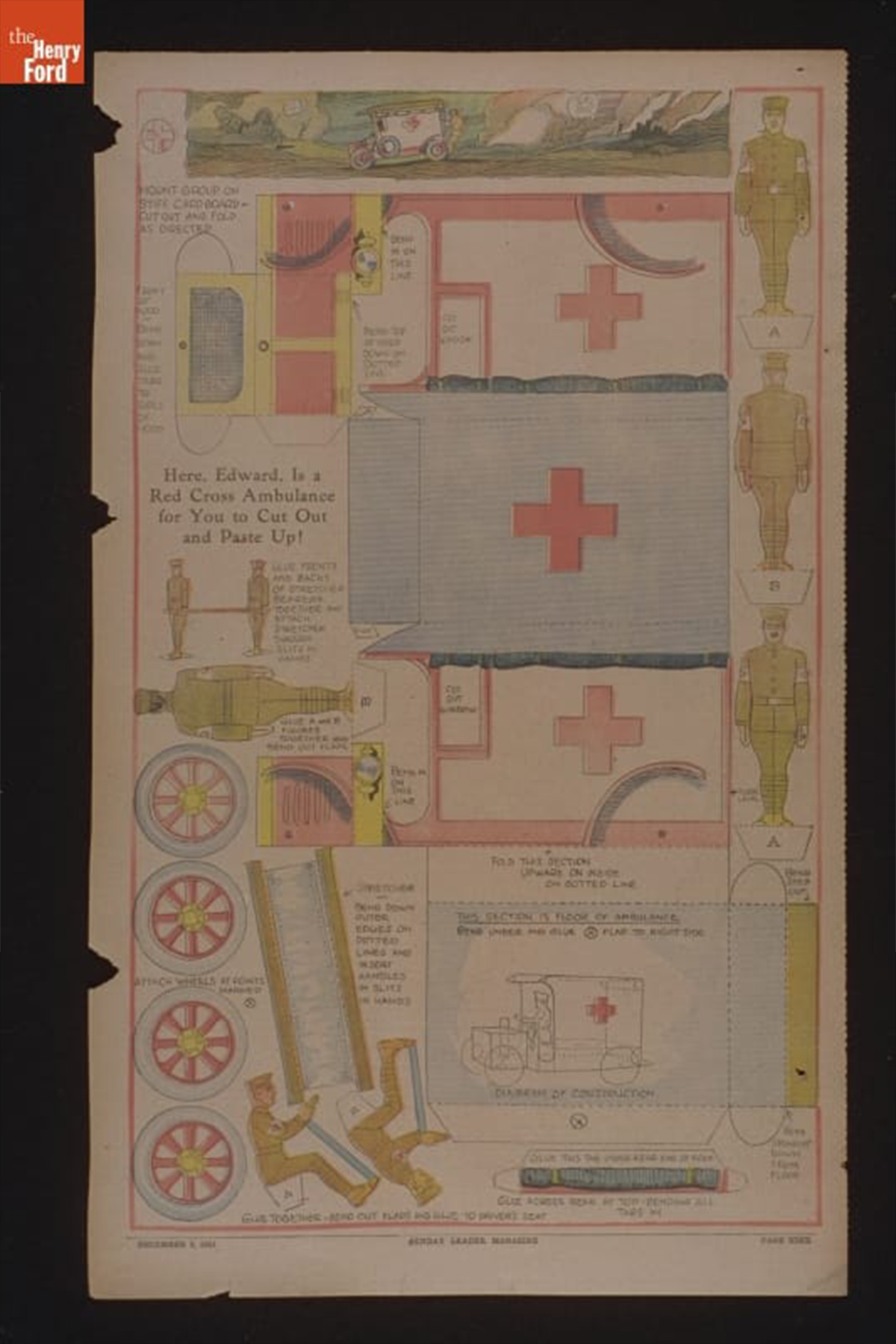

The American Red Cross, as a non-profit organization, depended on volunteers and charitable donations to meet need. During World War I, membership increased from 17,000 to over 30 million adults and older children. Contributions amounted to over $400 million in money and supplies. Ford Motor Company contributed $500,000 during the early years of World War I. The Red Cross turned around and used those funds to purchase Ford vehicles, nearly 1,000 of them, including 107 ambulances, for wartime use through the Motor Corps. Newspapers helped promote this work especially to young readers, as the following colorful cutout of a Ford ambulance represents.

World War I Red Cross Ambulance Cut-Out Paper Toy, December 9, 1917. / THF342142

Soon after war erupted in Europe in August 1939, urgent requests from the Red Cross began to reach wealthy Americans. Edsel Ford indicated his intention in May 1940 to support the fund drive required to meet the unprecedented need for assistance in war-torn Europe. He sent a postal telegram to W. J. Scripps of WWJ radio explaining that “Detroit’s share of the proposed relief fund can be raised only by the generous cooperation and support of everyone.”

Ford Motor Company maintained its support of the Women's Motor Corps during World War II as 45,000 drivers filled the Corps' ranks. This included African American chapters in some cities. The volunteers logged over 61 million miles ferrying Red Cross staff and supplies, couriering packages and messages, and occasionally assisting with Army and Navy transportation needs.

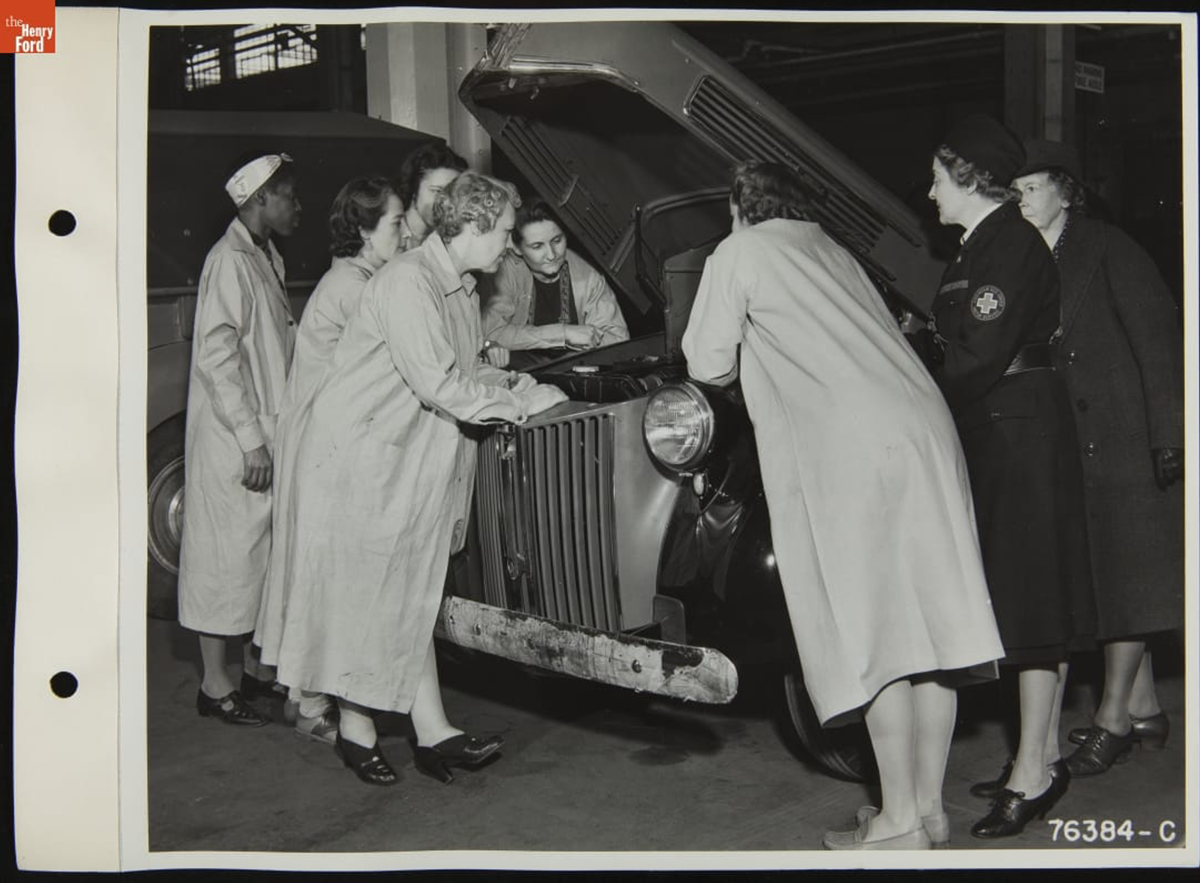

American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps members becoming familiar with engines during an auto maintenance class, Ford Motor Company, November 1941. / THF270093

Keeping the vehicles on the road required expertise. In 1941, Ford Motor Company began to provide automobile maintenance classes for the local Women’s Motor Corps at its Highland Park facilities. Instructors trained the volunteers in the mechanical skills they needed to keep their vehicles moving in times of emergency.

American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps members looking under the hood of a Ford ambulance, June 1942. / THF265816

Ford Motor Company donated its 29 millionth Ford automobile to the cause. The Super DeLuxe station wagon rolled off the Rouge Plant assembly line in April 1941. Edsel Ford presented this vehicle to the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross for use by the volunteers of the Women’s Motor Corps.

The 29 Millionth Ford and a driver from the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps, April 29, 1941. / THF270147

Workwear for Health Care

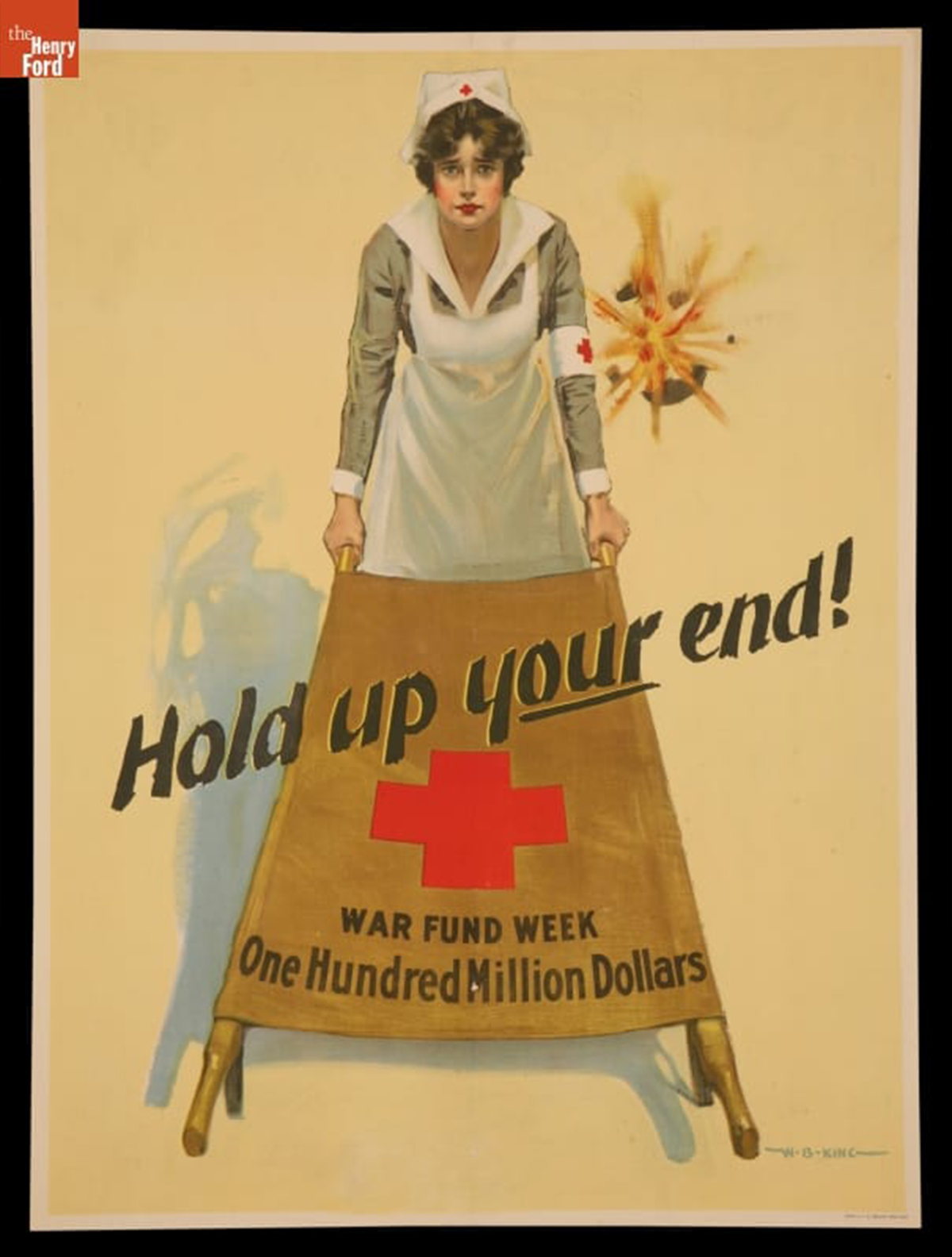

The American Red Cross hired trained nurses to assist doctors treating service men. Gray ladies nurse's aides provided an additional layer of volunteer support in military hospitals and boosted the morale of patients. They all wore the distinctive red cross emblem on their uniforms, adopted at the 1864 Geneva Convention to designate medical personnel during wartime. Active-duty Red Cross nurses wore plain white uniforms with bishop collars and caps and a dark blue cape lined in red during wartime, which was standard issue throughout World War II. As of December 24, 1915, active-duty nurses stationed abroad wore gray cotton crepe dresses with a white pique collar and cuffs, cap, and brassard. Public health nurses wore gray chambray. Uniform regulations decreed that the red cross appear prominently on the front of the cap, brassard, and nurse’s cape.

World War I era poster depicting the uniform of a Red Cross public health nurse, 1917. / THF112608

The Gray Lady Service also tended to soldiers in non-medical capacities during and between wars. They wrote letters, delivered bandages, or served snacks to men who needed physical and emotional comfort.

Gray Lady Service uniform, 1940-1945 (left). / THF173341; Gray Lady Service uniform, 1955 (right). / THF94383

The indoor uniform of the Gray Lady Service consisted of a gray cotton dress with detachable white collar and cuffs, a two-inch woven red cross on the upper pocket, and white epaulets worn on each shoulder. The red bars and chevrons worn on the sleeves conveyed length of service (Shirley Powers, “A Guide to American Red Cross Uniforms,” 2nd ed., 2006).

American Red Cross Volunteer Nurse's Aides, Peoria, Illinois, May 20, 1942. / THF289753

The American Red Cross and the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense specified details of the volunteer nurse’s aide uniform in November 1942. It consisted of a blue jumper-apron worn over a regulation white poplin blouse. Nurse’s aides donned the uniform after the first 34 hours of training, and the cap after completion of the 80-hour course. The full uniform included a three-inch joint Red Cross and Office of Civilian Defense nurse’s aide emblem, sewn on the upper left sleeve of the blouse, two inches below the shoulder seam. Chapters could recognize hours of service by awarding white stripes but only for those volunteering in hospital wards, in clinics, and in health agencies qualified for these.

National Blood Donor Service

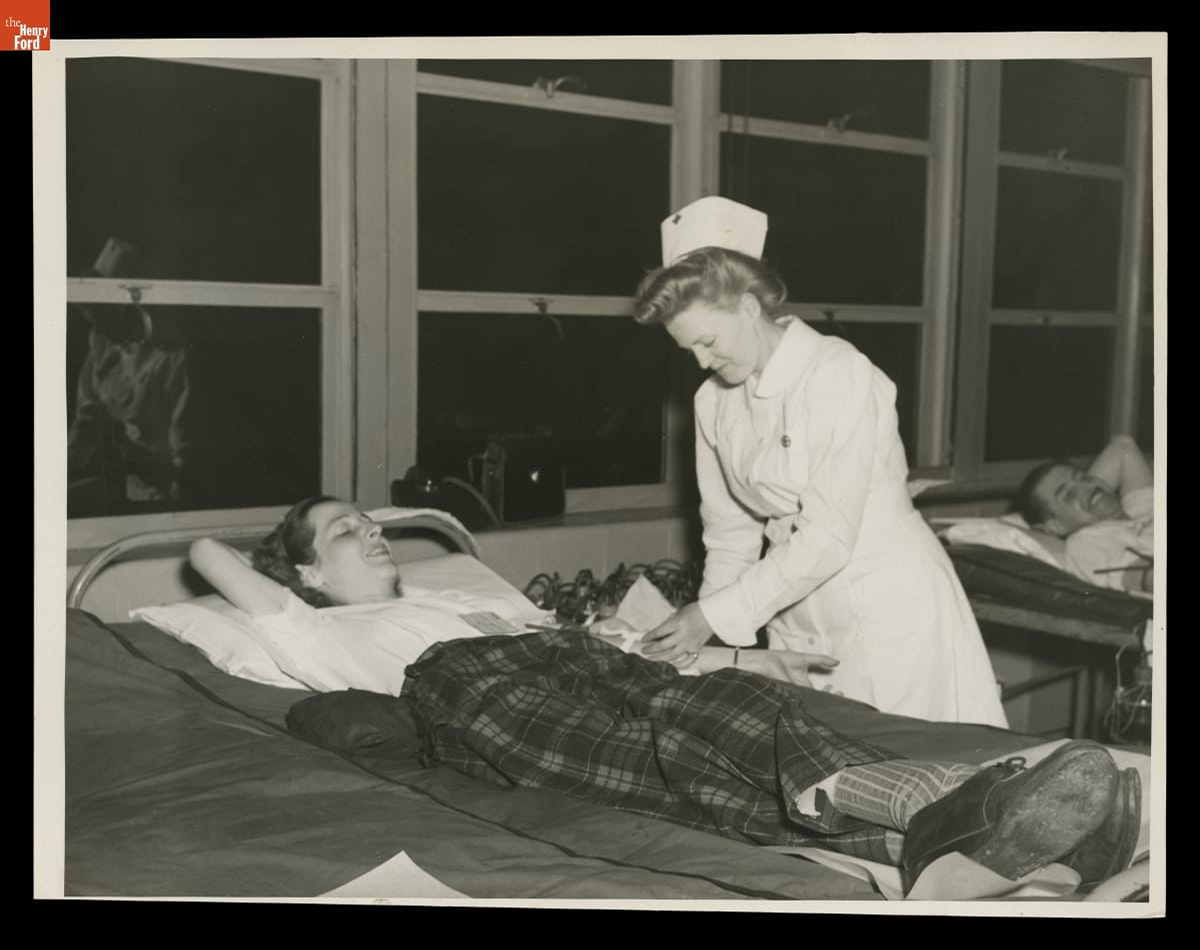

The American Red Cross began its National Blood Donor Service for the U.S. military in February 1941. Volunteers worked in the new blood banks, collecting blood and plasma donations and shipping them to hospitals caring for soldiers wounded in battle.

25,000th Blood Donor at the Ford Rouge Plant Pressed Steel Building, May 1943. / THF290075

Women working at Willow Run had their first chance to donate blood to the National Blood Donor Service in November 1944. The Ford Motor Company built its Willow Run Bomber Plant in 1941. Approximately one-third of the labor force were women. They performed office work but also drafted designs and worked on the assembly line, riveting and welding B-24 bomber components. At the plant's peak in 1944, Willow Run crews produced an average of one bomber every 63 minutes.

A Red Cross nurse draws blood from a female Ford Motor Company employee at Willow Run Bomber Plant, November 27, 1944. / THF728198

Canteen Girls and Donut Dollies

The female Red Cross volunteers who faced some of the most dangerous situations during World War II included those who served overseas as Canteen Girls or Donut Dollies. This work began during World War I in service to soldiers on the move, as a 1918 photograph of an African American woman in Detroit, handing bananas to soldiers indicates. During World War II, women traveled in mobile club wagons that often operated close to intense fighting. Critics claimed that the young women, all college educated and carefully selected, assumed significant personal risk. Julia Ramsey, author of “’Girls’ in Name Only” (Auburn University, 2011), claims that these women had access to battle and combat that no civilian women had previously. Paige Gulley, author of “After All, who takes care of the Red Cross’s morale?” (Chapman University, 2021), analyzed primary source created by the volunteers themselves to explain how women relied on each other to manage stress and meet expectations.

These examples represent the breadth of service and due diligence that female volunteers provided to the American Red Cross. The organization was not perfect and need often exceeded the capacity of staff and volunteers to meet it. The opportunity to work for humanitarian causes drew women who wanted to do something to support the U.S. cause during World War II. In addition to the options described above, women pursued other outlets through the Red Cross that relieved stress for individuals and families in crisis.

Debra A. Reid, Curator, Agriculture and the Environment, with Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life, The Henry Ford

Series | |

|---|---|

Themes |