Shoe-Fitting Fluoroscope: Scientific Advancement or Sales Tactic?

On November 8, 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered electromagnetic radiation, or invisible light, which he dubbed x-rays; immediately they became a huge fad, used for everything from photographic filters to miracle cures for a variety of ailments. X-rays bridged the gap between the public's interest in scientific advancement and commerce. One fascinating artifact in The Henry Ford's collection demonstrates the X-ray craze well: a shoe-fitting fluoroscope.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. X-Ray Shoe Fitters, Inc., a subsidiary of the Adrian Company of Madison, Wisconsin, was one of largest manufacturers of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and made this X-ray. / THF803832

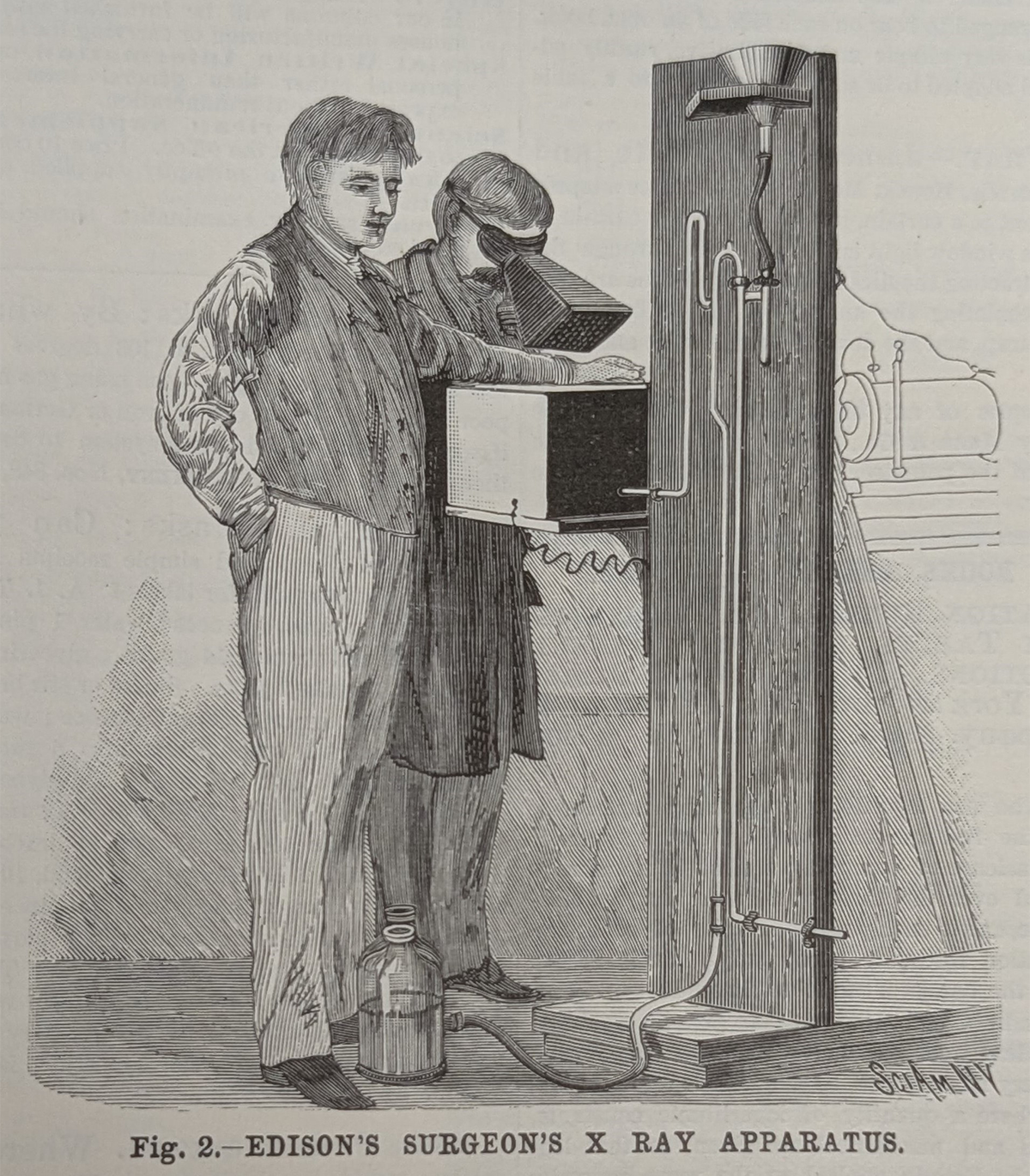

Fluoroscopes are real-time, continuously moving X-ray images — like an X-ray movie. Thomas Edison created the first commercially available fluoroscope in 1896 by adapting the basic principle of static X-rays.

Illustration from Scientific American announcing Edison's fluoroscope in April 1896. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

X-rays are beams of invisible light moving in short wavelengths, which pass through objects and create negative images of them on a fluorescent screen. What you see in the negative image depends on how much radiation an object can absorb. More dense objects like bones absorb more radiation, so they show up as white on an X-ray picture; less dense objects like muscle tissue absorb less radiation, so they show up as dark on an X-ray picture. Edison's fluoroscope allowed people to look at their bones in real-time when they placed their bodies between a cathode tube that made X-rays and a fluorescent screen that displayed the images created.

Box of fluoroscope Slides, 1895-1905. / THF157985

In the early days of fluoroscopy, they were primarily used in hospitals or as novelties. In 1919, Jacob Lowe, owner of a Boston-based X-ray laboratory, filed a patent for the first fluoroscope explicitly for fitting shoes. Lowe saw the problem of ill-fitted shoes causing discomfort in the short term and foot deformities in the long term; his machine would allow the customers to see their feet inside of their shoes and would presumably prevent future issues.

Shoe-fitting fluoroscope, circa 1936. To use a shoe-fitting fluoroscope, customers would stand on this side of the X-ray and put their feet in the chamber at the bottom. / THF803822

To use Lowe's fluoroscope, customers placed their feet on the enclosed platform where the X-ray tube was and looked through one of the fluoroscope's viewfinders to check their feet on the fluorescent screen. The three viewfinders also allowed simultaneous observation: for example, a salesperson, a child trying on shoes, and the child's parent.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. A customer could see a fluoroscope of their feet from the viewing chamber above. / THF803831

The patent was granted in 1927, and Lowe assigned the patent to the Adrian Company in Madison, Wisconsin, which began manufacturing shoe-fitting fluoroscopes in 1922. For the next thirty years, shoe-fitting X-rays became ubiquitous in shoe stores across the world.

Did X-raying feet actually help customers and store employees fit shoes? In the 1990s, a former shoe shop clerk was interviewed about shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and revealed that the machines did not help him properly size customers. Additionally, he did not know any salespeople who felt the machine truly helped them. Shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were essentially a marketing gimmick that incentivized customers to buy shoes.

During the 1920s, businesses began to focus on ways to drive consumer habits through driving demand. For example, Charles Kettering of General Motors championed the idea of selling "newness" to customers in his 1929 essay "Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied": "If everyone were satisfied, no one would buy the new thing because no one would want it […] You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times." Kettering's philosophy was pivotal to understanding why fluoroscopes were popular among shoe sellers. Even the Adrian Company's shoe fitting X-ray manual touted the unverified statistic that 75% of people wore shoes too small for them and therefore needed new shoes. That statistic could be repeated to customers to bolster dissatisfaction and drive sales. Additionally, there was a perception that using fluoroscopes was a necessary form of consumer safety. The "see for yourself" nature of the fluoroscope created the illusion of an "objective" way for salespeople to determine if new shoes were necessary.

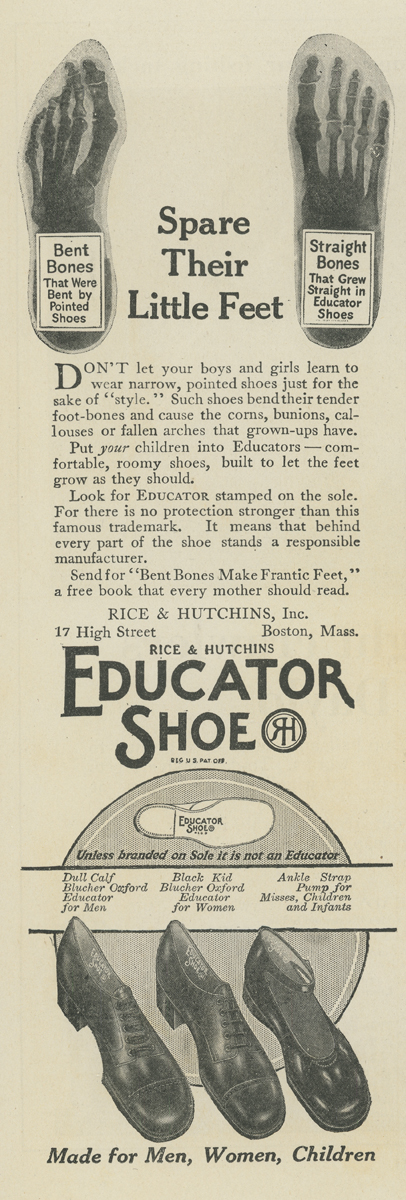

"Spare Their Little Feet," 1917-1921. / THF723224

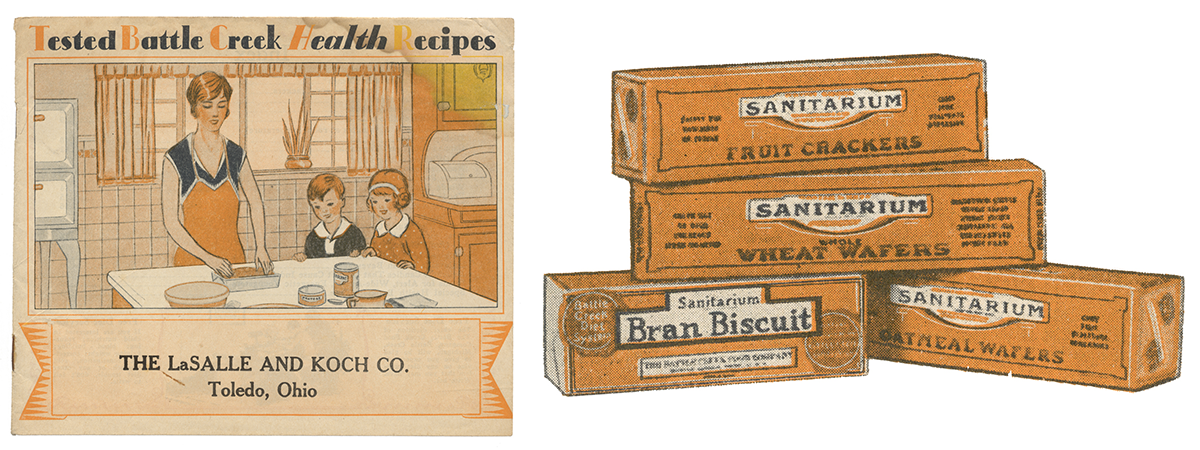

The fluoroscopic sales tactic was used on women especially by playing into the idea of "scientific motherhood." At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an increasing expectation that women needed the latest technological advancements and advice to raise their families correctly. The concept of "scientific motherhood" was utilized to great effect in advertising, where companies marketed their products with sometimes-dubious claims of "expert approval" or "rigorous scientific testing."

Tested Battle Creek Health Recipes, 1928. This recipe booklet is a great example of scientific motherhood in advertising. The booklet was sold along with crackers and cookies but used words like "health," "sanitarium," and "tested" to imply that the food was healthy for families like the one shown on the cover. / THF17004 and THF17005

With the fluoroscope, shoe store owners played into the medicalization of mothering. Salespeople often recommended annual or even quarterly foot X-rays for children in the way doctors might recommend yearly physicals. Repeat X-rays created repeat customers.

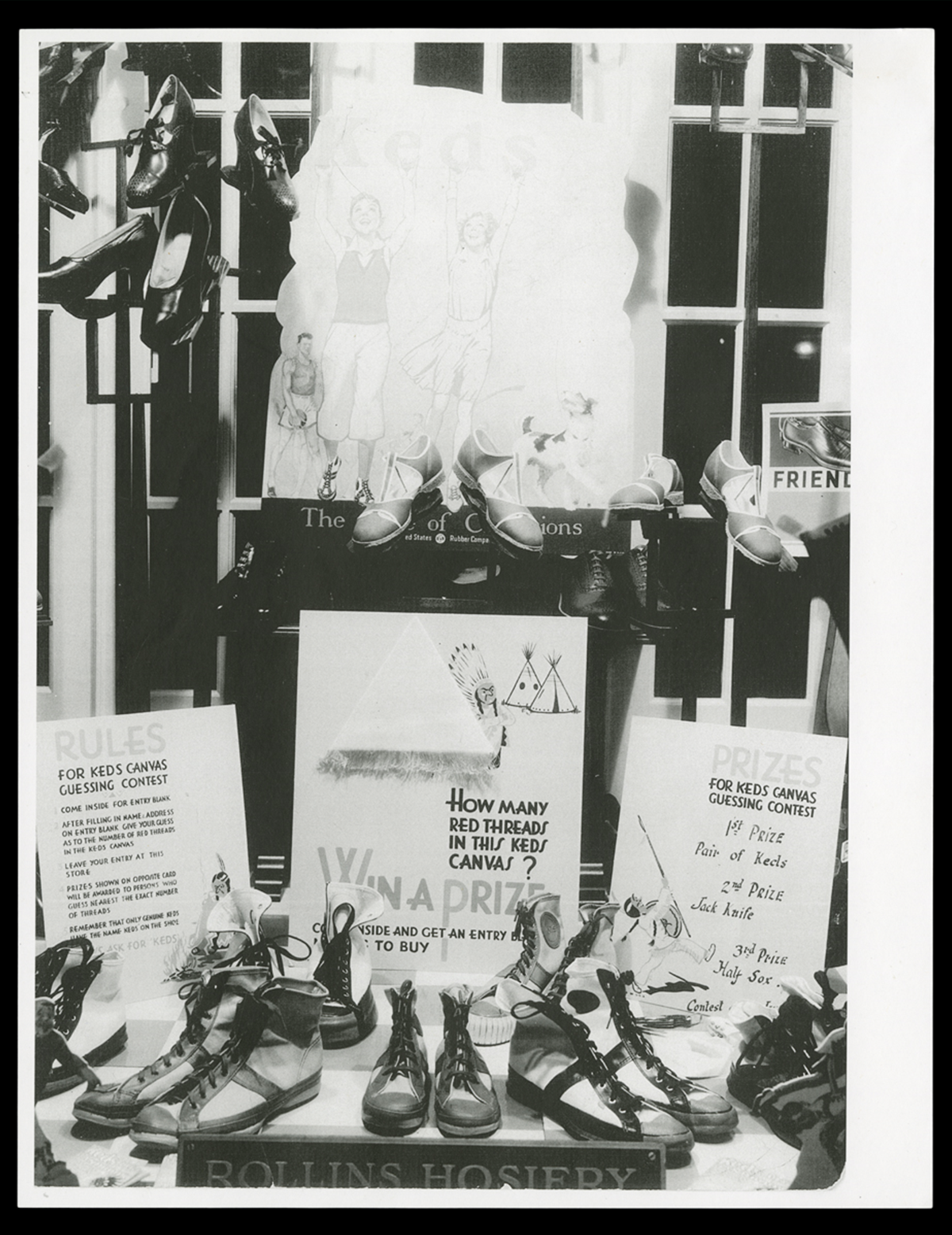

Additionally, kids loved fluoroscopes! Stores would advertise their shoe-fitting fluoroscopes alongside other child-friendly customer perks like balloons, contests, and candy.

Keds window display at the Campbell Boot Shop, Charlevoix, Michigan, circa 1930. This shoe store used window display contests to attract young customers with the possibility of brand new shoes. / THF723228

Until the late 1940s, fluoroscopes were used everywhere from first aid stations on job sites to quality control inspections on orange tree farms. However, the lack of regulation for radioactive machines endangered people. Several high-profile incidents eroded the public's trust in fluoroscopy. For example, between 1941 and 1943, 57 California Shipbuilding Corp. workers received mutilating radiation injuries after using the company's first aid fluoroscope. This lack of regulation also affected shoe fitting X-rays. A 1948 study of Detroit-area shoe stores showed that over 20% of stores' fluoroscopes produced 16 to 75 röntgens — the measure of radioactive discharge — per minute. At the time the maximum radiation exposure recommendation was .3 röntgen per week.

X-ray tube, circa 1915. Vacuum tubes like this are used to produce X-rays in fluoroscopes and other forms of radiography. / THF174376

In 1950, Carl Braestrup, senior physicist for New York City hospitals, was one of the first health officials to warn the public that shoe-fitting fluoroscopes could cause radiation burns and leukemia, especially in children. That same year, city health officers in Los Angeles reported that shoe-fitting fluoroscopy caused abnormal bone growth in children. But shoe stores were initially reluctant to get rid of their machines; Los Angeles shoe store owners claimed that parents' demand for X-rays drove them to keep them. It took until 1957 for Pennsylvania to become the first state to ban shoe-fitting fluoroscopes.

In many ways, the shoe X-ray represents a time when science and commerce seemed to go hand-in-hand but went toe-to-toe instead. Innovations, like the X-ray, were used to turn profits but also harmed the public.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope being photographed for digitization. / Photo by Staff of the Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Facebook Comments