Take Me to the River: Managing Water Runoff at The Henry Ford

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 7/10/2025 |

Take Me to the River: Managing Water Runoff at The Henry Ford

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 7/10/2025 |

The roof of The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation covers nearly 12 acres. A one-inch rainfall results in almost 326,000 gallons of water landing on that expansive roof.

Where does the runoff go?

The architect, Robert O. Derrick, and landscape designer, Jens Jensen, who planned the building and grounds, cloaked the infrastructure that managed that runoff deftly. The following article walks you through the route that the water takes as downspouts and pipes move it from the museum roof to a 2.5-acre pond behind the museum and on to the nearby River Rouge. Today the pond, out of sight to the public, plays a vital role in reducing the risk of flooding and silt buildup in the nearby River Rouge, and it enables the reuse of runoff to irrigate the grounds.

Pond located north of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and southeast of the Dearborn Transit Center (upper right). / Drone photograph courtesy of Bart Fraley.

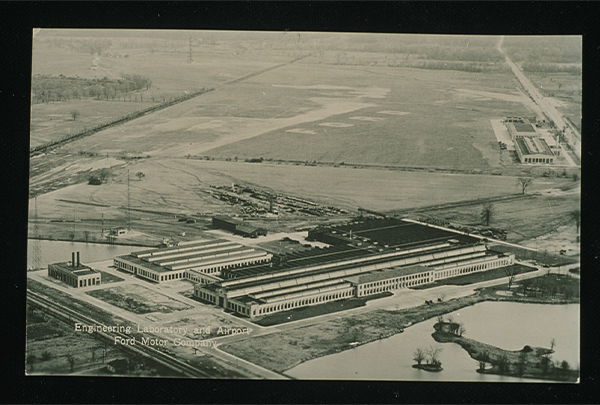

The pond predated the 1929 founding of The Edison Institute.. It and another set of ponds to the west resulted from clay extraction by a local brickyard. The Ford Motor Company built a powerhouse next to the eastern most pond at the Ford Engineering Laboratory. This pond became the holding tank for runoff from the museum roof.

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

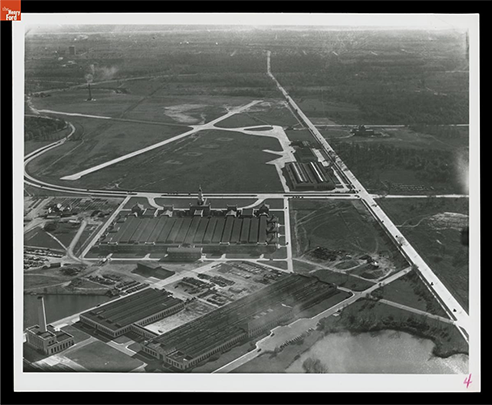

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Landscape architect Jens Jensen mapped “the pond” behind “the museum building” in December 1931. Moving water from the roof to the pond begins with downspouts embedded into museum walls and structural columns throughout the Great Hall. Because this flow enters the system above ground, gravity moves it into the drainage infrastructure under the museum.

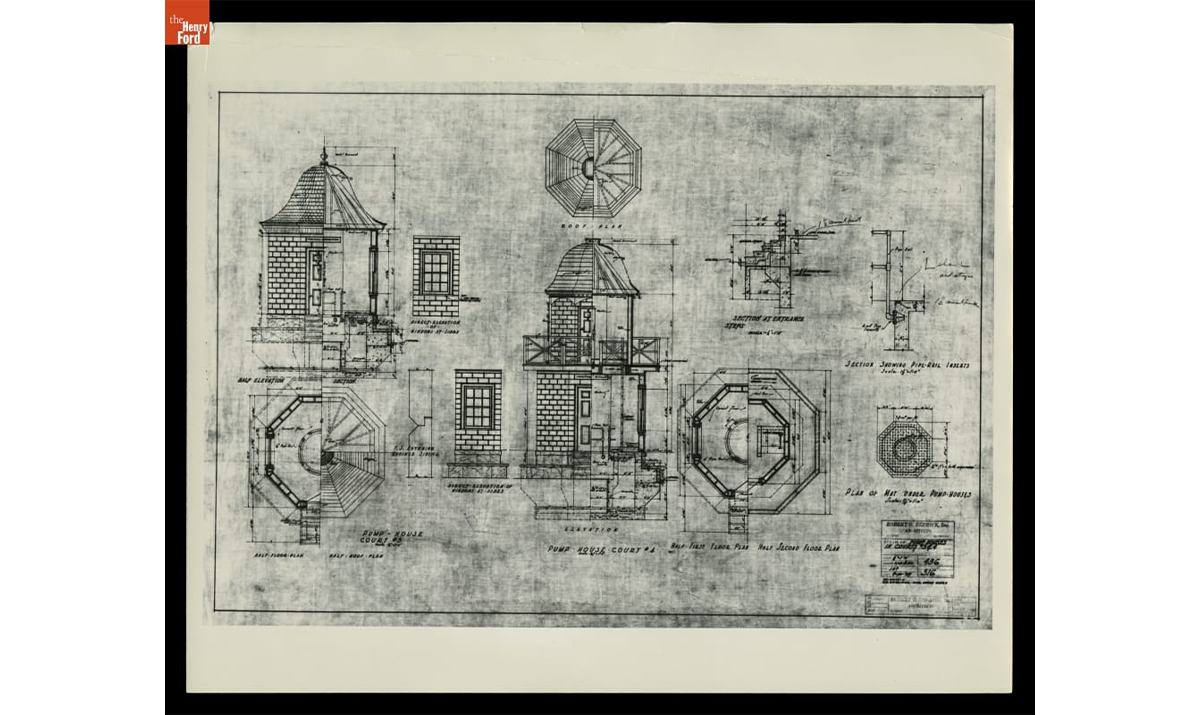

Rainwater also flows into yard drains around the museum. Since the yard drains are below grade, the system needed pumping stations to collect and pump water vertically to send water up and into the roof-water collection system closer to ground level. Architect Robert O. Derrick incorporated two pumphouses into his museum plans in 1928 to house these pumping stations.

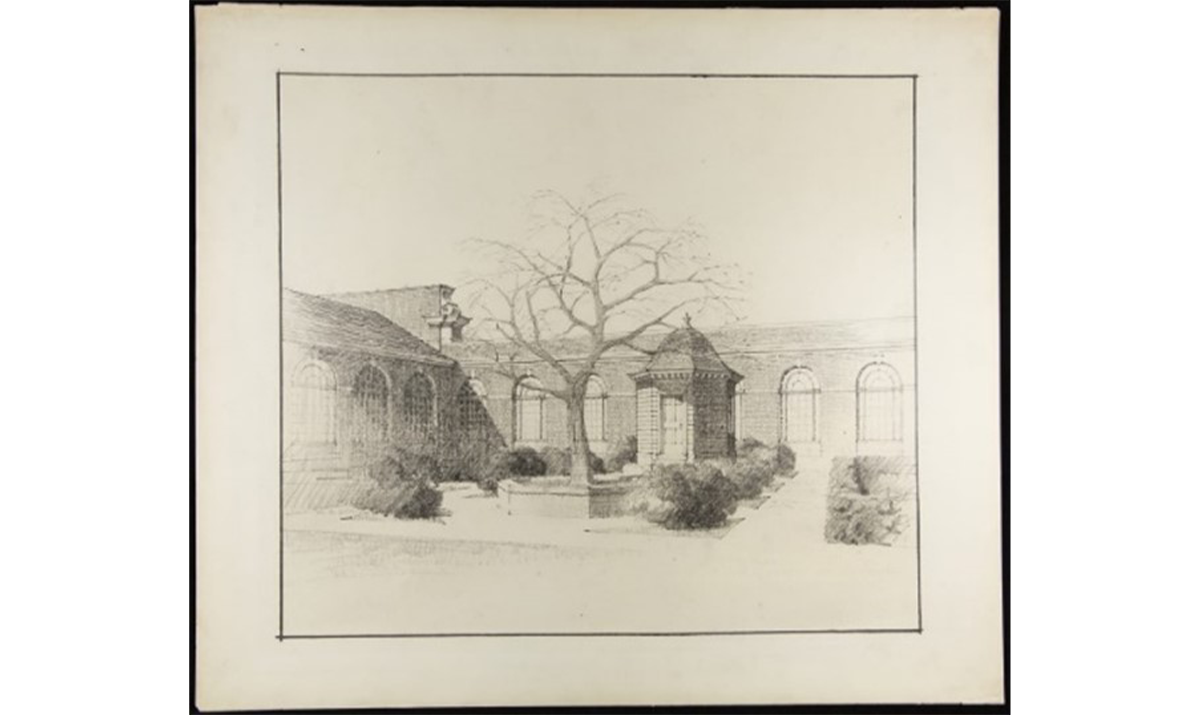

Derrick, noted for his Colonial-revival designs, disguised the pumping stations in reproductions of other structures popular during the Colonial-revival era. The inspiration included a garden feature from Mount Vernon, home of George and Martha Washington, and the observatory that astronomer David Rittenhouse built in Philadelphia after he moved there in 1770. Rittenhouse gained international attention in 1769 because of his observation of the transit of Venus. His relocation to Philadelphia in 1770, the largest city in the Colonies at the time, facilitated his engagement with the vibrant scientific community there. Contemporaries described his Philadelphia observatory as “a small but pretty convenient octagonal building, of brick” [William Barton, Memoirs of the Life of David Rittenhouse (1813), note 111].

Virginia Court pumphouse based on a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

Pennsylvania Court pumphouse based on Rittenhouse’s observatory, 1928 / THF294392

The stations, located in each of the two large courtyards on each side of the main entrance to the museum, hold water and pump it into the stormwater infrastructure as needed.

Details of pumphouses in museum courtyards, drawn by Robert O. Derrick, Inc., Architects, 1929 / THF98551

Gravity facilitates rainwater flow to a 24-inch main line under the museum, which channels runoff to the basement of the powerhouse in the back of the museum. Facilities staff replaced the entire ductile iron system in the powerhouse basement during 2025 with stainless steel. This was the first replacement since the entire system was built in 1929.

Storm-pump system in the powerhouse basement. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

Two 75-horsepower motors, located in the basement of the power house, handle large storms. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

In what's designed as a "wet" system, water always fills the lower portion of the infrastructure. As rainwater drainage increases the pressure in the system, it pushes water out of the museum and into the retention pond.

What happens after rainwater runoff enters the pond?

The retention pond allows sediment to settle out of the water within the pond rather than in the River Rouge. It also accumulates for later use to water the grounds around the museum, Lovett Hall, and the Josephine Ford Plaza. A large irrigation pump draws water from the pond to the irrigation piping.

The stormwater management system within Greenfield Village converges near the Suwanee dock and flows into the Suwanee Lagoon. The water in the lagoon is regulated by a drain that flows into the Oxbow which connects to the River Rouge. Facilities staff can use a pumping station at the Oxbow to increase the rate of pumping into the River Rouge in case of excessive rainfall. That pumping station also works as a protection. If the River Rouge is too high, a valve can be exercised to prevent backward flow into The Henry Ford's stormwater management system.

Each pond in the Village serves as a large holding tank with an inlet on one side and outlet on the other, depending on which direction the water needs to flow to reach the Suwanee.

Mill pond construction in the Greenfield Village craft area, March 2003 / THF10348

Mill pond in Greenfield Village’s craft area. / Photograph courtesy of Lee Cagle, May 2018.

Water within the system irrigates lawns and gardens within the Village. A large irrigation pump near Henry Ford Academy draws water from the Suwanee Lagoon for this purpose.

Overall, the water management system has been integral to The Henry Ford’s efforts to reduce waste and reuse runoff. An overview of five years of Green Museum Work undertaken from 2019 through 2024 acknowledges this system as one of the historic precedents and an inspiration for current efforts. It takes staff expertise, financial commitment, and regular maintenance to continue such efforts, but the investment pays off in reduced water bills and healthier riverine ecosystems. Updates to the system during 2025 should prepare it for the next 100 years.

Jon Bennett is Assistant Construction Manager and Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. The title of this blog was inspired by Al Green’s and Mabon “Teenie” Hodges 1974 song by the same title.

Themes |

|---|