Anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment

| Written by | Donna R. Braden |

|---|---|

| Published | 12/4/2020 |

Anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment

| Written by | Donna R. Braden |

|---|---|

| Published | 12/4/2020 |

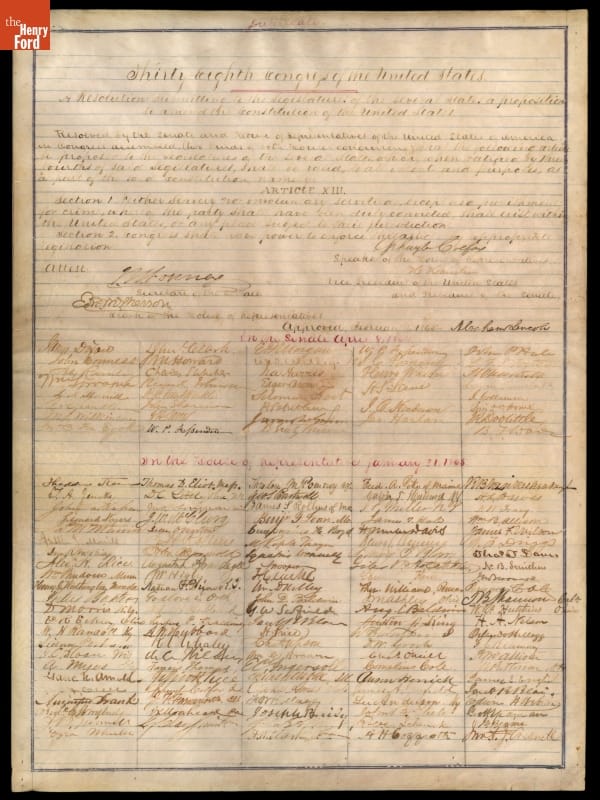

Joint Resolution of the United States Congress, Proposing the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery, February 1, 1865 / THF118475

December 6, 2020, marks the 155th anniversary of the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which legally abolished slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation, first made public by President Abraham Lincoln in September 1862, laid the foundation for this amendment. With this presidential proclamation and executive order, President Lincoln hoped to counteract severe Union losses during the Civil War by calling on all Confederate states to rejoin the Union within 100 days (by January 1863) or the proclamation would declare enslaved people “thenceforward, and forever free.” On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln proceeded to sign this document, announcing freedom to all enslaved people in the Confederacy. It helped enlist needed support for the war from abolitionists and pro-union and anti-war supporters. But it was not a legal document, and Lincoln knew it.

President Lincoln and his allies in Congress soon began working to enact a constitutional amendment that would legally abolish slavery. Various versions were brought before Congress until, on April 8, 1864, the strongly pro-Union Senate approved this version of the Thirteenth Amendment as we know it today:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

However, this amendment failed to pass in the House of Representatives, whose members were more split on their views. The amendment stalled until November of that year, when, upon his own reelection and with like-minded Republican gains in the House, President Lincoln urged members of the Congress to reconsider the measure and give it their utmost urgency. He enlisted members of his Cabinet and selected allies in the House to help him sway enough House member votes for the amendment to pass.

On January 31, 1865, it barely squeaked by with the requisite two-thirds majority. Upon learning of the final vote, pro-Union and anti-war members of the House erupted in shouts and cheers, while outside spectators who had filled the Capitol’s galleries (both Black and white) wept tears of joy.

On February 1, 1865, members of Congress signed this Joint Resolution of the Thirteenth Amendment, indicating that it had passed by both the Senate and the House of Representatives but had yet to receive state ratification. Although not legally required to do so, President Lincoln signed it as well. Immediately, Lincoln’s foes in both Congress and the press criticized him for wielding unseemly presidential power. But Lincoln was undeterred. Celebrating that evening, Lincoln happily announced, “This amendment is a King’s cure for all evils. It winds the whole thing up.”

It did help wind up the war. Its primary motive was, in fact, to preserve the Union by destroying the cornerstone of the Southern Confederacy. Sadly, on April 15, just as the war was winding down, President Lincoln was assassinated. Afraid that slavery might be re-established by individual states, Radical Republicans in Congress determinedly pushed the Thirteenth Amendment forward for state ratification. It was finally ratified by the requisite three-quarters of states on December 6, 1865—the date we are now commemorating.

Unfortunately, the Thirteenth Amendment was not a “cure for all evils.” Some Southern states were already instituting black codes, denying African Americans basic rights. The Thirteenth Amendment was followed by a Fourteenth and a Fifteenth—legally guaranteeing African Americans the basic rights of citizenship and the ability to vote. But these were just legal documents. Enforcing them was another matter, one fraught with violence and discrimination. African Americans would face an ongoing struggle for freedom and justice.

This is one of a limited number of original manuscript copies known to survive of the February 1, 1865, Joint Resolution of the US Congress, proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery. Lincoln’s signature was added by another hand.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Series | |

Themes |