Thunderbird Soars at Motor Muster

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Once again Father’s Day weekend brought a favorite event to Greenfield Village. Our 2025 Motor Muster, held June 14-15 and celebrating car culture from 1933 to 1978, featured more than 650 automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, military vehicles, and bicycles. Each Motor Muster features a special theme, and this time our spotlight fell on the Ford Thunderbird, seventy years after the sporty personal car was introduced for the 1955 model year. Thunderbird was a hit over eleven different styling generations through 2005, taking only a brief pause in production from 1998 to 2001.

Detroit Central Market housed Thunderbirds from seven of the car’s eleven styling generations, including a couple of post-1978 examples. / Image by Matt Anderson

We wanted to showcase Thunderbird properly, so our friends at the Water Wonderland Thunderbird Club and the Vintage Thunderbird Club International helped us pull together a selection of some of the best T-Birds pull together a display in Detroit Central Market featuring some of the best T-Birds ever built Detroit Central Market. We had cars from seven of Thunderbird’s eleven generations. Together, they represented the original two-seat “Little Birds” of the mid-1950s, the four-seat “Square Birds” of the late 1950s, the angular “Bullet Birds” of the early 1960s, and the larger luxury-focused Thunderbirds of the early 1970s. From The Henry Ford’s own collection, we included our 2002 Ford Thunderbird, serial number one from the final generation, and our 1962 Budd XT-Bird, which Budd pitched to Ford in hopes of reviving the partnership that had Budd building body components for two-seat T-Birds several years earlier. Our 2002 model wasn’t the only post-1978 T-Bird in the show. We also included a 1994 Thunderbird representing the model’s tenth generation.

Thunderbird Jr. kiddie cars were built in cooperation with Ford from 1955 to 1967. / Image by Matt Anderson

There was another big—make that small— feature in Detroit Central Market. Fourteen Thunderbird Jr. cars added to the fun. Built in Mystic, Connecticut, with the blessing of Ford Motor Company, the Thunderbird Jr. was a scaled-down version of the real thing powered either by an electric motor or a single-cylinder gasoline engine. The junior cars were updated each year to match the look of the real T-Bird, and paint colors were all factory-correct. Smaller Thunderbird Jr. cars, roughly one-quarter size, were intended for children and either given away by Ford dealers or sold by high-end retailers like FAO Schwarz. Larger versions, about one-third size, were used at carnivals and amusement parks. About 5,000 Thunderbird Jr. cars were produced from 1955 to 1967. The fourteen examples at Motor Muster may have been the largest gathering of these little cars since the factory closed nearly sixty years ago.

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

From the Armington & Sims Machine Shop to the Daggett Farmhouse, Greenfield Village was packed with historic vehicles. A visitor might easily spend all day walking around to see everything. But for those who preferred to let the show come to them, we offered pass-in-review programs throughout the weekend. As spectators relaxed on shaded bleachers, expert narrators offered insights and expertise on participating vehicles that rolled through in a steady chronological parade. While most of these presentations were organized by decade, we had special sessions devoted to commercial vehicles, race cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and —of course— Thunderbirds.

The cars were complemented by a variety of musical performances and historical vignettes. At Town Hall in the heart of the village, the Village Cruisers offered a selection of 1950s vocal pop perfect for the chrome-and-tailfins era. At the same location, Larry Callahan and the Selected of God Quartet sang stirring freedom songs from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Their performance offered a wonderful preview of programming to come with the opening of the Jackson Home next year. The 1970s came alive through the Mach I band as they played classic rock hits both at the gazebo near Ackley Covered Bridge and in a larger Saturday evening concert on Main Street.

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pedal-powered transportation is in vogue at The Henry Ford thanks to Bicycles: Powering Possibilities, a temporary exhibit now on view in the Collections Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. There were many bikes to enjoy at Motor Muster, from an eccentric-hub Ingo-Bike like this one in the museum’s collection, to an early 1970s Schwinn Twinn tandem that allowed two cyclists to ride together. And just as Motor Muster vehicles need not be motorized, they don't have to travel on land either. We celebrated outboard boating’s golden age on the shores of Suwanee Lagoon. The fascinating display of boats and engines was titled “Tailfins and Two-Tones,” reflecting a couple of 1950s design fads that were found on land and sea alike.

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

As is tradition, Motor Muster ended on Sunday with our awards ceremony. We presented trophies to vehicles from each decade based on popular-choice ballots submitted by show participants and visitors. We also gave Curator’s Choice prizes to a pair of unrestored vehicles. This year’s unrestored winners included, fittingly, a 1966 Ford Thunderbird and a 1974 Ford Gran Torino. The full list of 2025 Motor Muster winners is available here. The ceremony put a perfect cap on another wonderful weekend.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

On November 8, 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered electromagnetic radiation, or invisible light, which he dubbed x-rays; immediately they became a huge fad, used for everything from photographic filters to miracle cures for a variety of ailments. X-rays bridged the gap between the public's interest in scientific advancement and commerce. One fascinating artifact in The Henry Ford's collection demonstrates the X-ray craze well: a shoe-fitting fluoroscope.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. X-Ray Shoe Fitters, Inc., a subsidiary of the Adrian Company of Madison, Wisconsin, was one of largest manufacturers of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and made this X-ray. / THF803832

Fluoroscopes are real-time, continuously moving X-ray images — like an X-ray movie. Thomas Edison created the first commercially available fluoroscope in 1896 by adapting the basic principle of static X-rays.

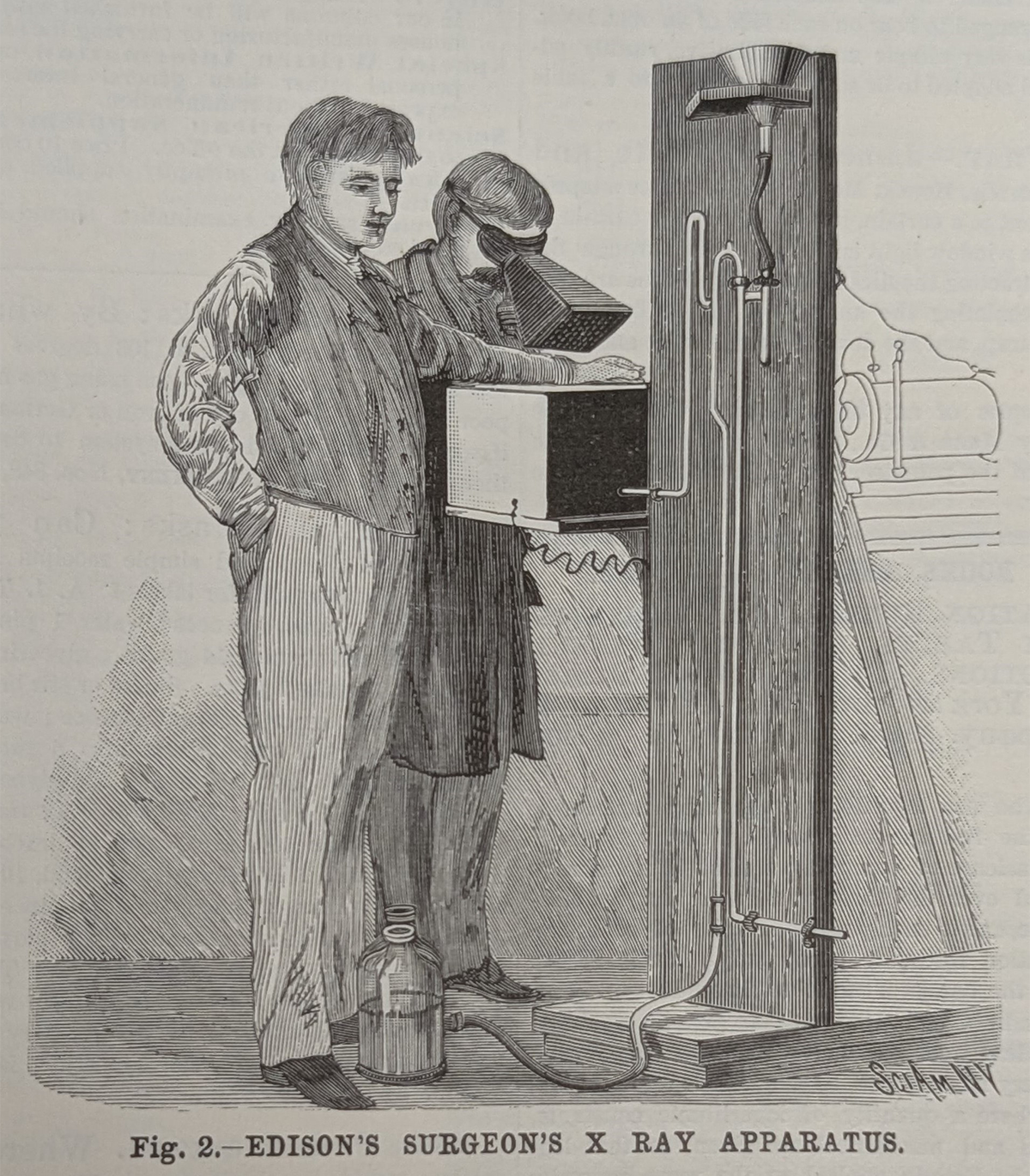

Illustration from Scientific American announcing Edison's fluoroscope in April 1896. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

X-rays are beams of invisible light moving in short wavelengths, which pass through objects and create negative images of them on a fluorescent screen. What you see in the negative image depends on how much radiation an object can absorb. More dense objects like bones absorb more radiation, so they show up as white on an X-ray picture; less dense objects like muscle tissue absorb less radiation, so they show up as dark on an X-ray picture. Edison's fluoroscope allowed people to look at their bones in real-time when they placed their bodies between a cathode tube that made X-rays and a fluorescent screen that displayed the images created.

Box of fluoroscope Slides, 1895-1905. / THF157985

In the early days of fluoroscopy, they were primarily used in hospitals or as novelties. In 1919, Jacob Lowe, owner of a Boston-based X-ray laboratory, filed a patent for the first fluoroscope explicitly for fitting shoes. Lowe saw the problem of ill-fitted shoes causing discomfort in the short term and foot deformities in the long term; his machine would allow the customers to see their feet inside of their shoes and would presumably prevent future issues.

Shoe-fitting fluoroscope, circa 1936. To use a shoe-fitting fluoroscope, customers would stand on this side of the X-ray and put their feet in the chamber at the bottom. / THF803822

To use Lowe's fluoroscope, customers placed their feet on the enclosed platform where the X-ray tube was and looked through one of the fluoroscope's viewfinders to check their feet on the fluorescent screen. The three viewfinders also allowed simultaneous observation: for example, a salesperson, a child trying on shoes, and the child's parent.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. A customer could see a fluoroscope of their feet from the viewing chamber above. / THF803831

The patent was granted in 1927, and Lowe assigned the patent to the Adrian Company in Madison, Wisconsin, which began manufacturing shoe-fitting fluoroscopes in 1922. For the next thirty years, shoe-fitting X-rays became ubiquitous in shoe stores across the world.

Did X-raying feet actually help customers and store employees fit shoes? In the 1990s, a former shoe shop clerk was interviewed about shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and revealed that the machines did not help him properly size customers. Additionally, he did not know any salespeople who felt the machine truly helped them. Shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were essentially a marketing gimmick that incentivized customers to buy shoes.

During the 1920s, businesses began to focus on ways to drive consumer habits through driving demand. For example, Charles Kettering of General Motors championed the idea of selling "newness" to customers in his 1929 essay "Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied": "If everyone were satisfied, no one would buy the new thing because no one would want it […] You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times." Kettering's philosophy was pivotal to understanding why fluoroscopes were popular among shoe sellers. Even the Adrian Company's shoe fitting X-ray manual touted the unverified statistic that 75% of people wore shoes too small for them and therefore needed new shoes. That statistic could be repeated to customers to bolster dissatisfaction and drive sales. Additionally, there was a perception that using fluoroscopes was a necessary form of consumer safety. The "see for yourself" nature of the fluoroscope created the illusion of an "objective" way for salespeople to determine if new shoes were necessary.

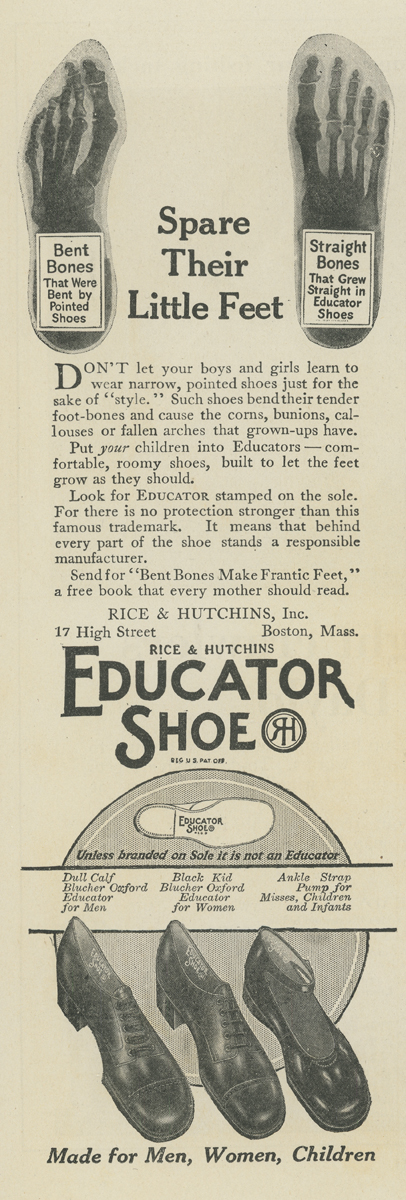

"Spare Their Little Feet," 1917-1921. / THF723224

The fluoroscopic sales tactic was used on women especially by playing into the idea of "scientific motherhood." At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an increasing expectation that women needed the latest technological advancements and advice to raise their families correctly. The concept of "scientific motherhood" was utilized to great effect in advertising, where companies marketed their products with sometimes-dubious claims of "expert approval" or "rigorous scientific testing."

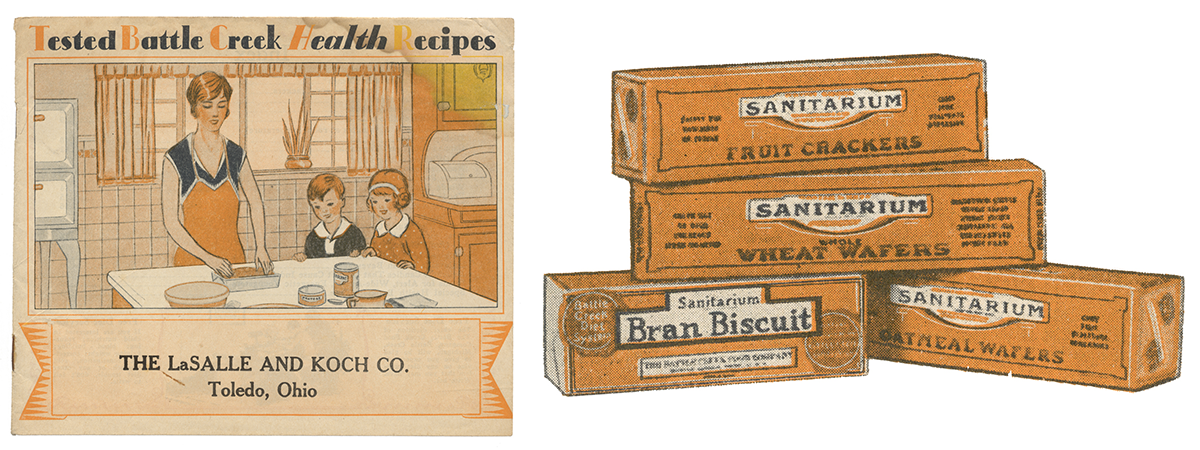

Tested Battle Creek Health Recipes, 1928. This recipe booklet is a great example of scientific motherhood in advertising. The booklet was sold along with crackers and cookies but used words like "health," "sanitarium," and "tested" to imply that the food was healthy for families like the one shown on the cover. / THF17004 and THF17005

With the fluoroscope, shoe store owners played into the medicalization of mothering. Salespeople often recommended annual or even quarterly foot X-rays for children in the way doctors might recommend yearly physicals. Repeat X-rays created repeat customers.

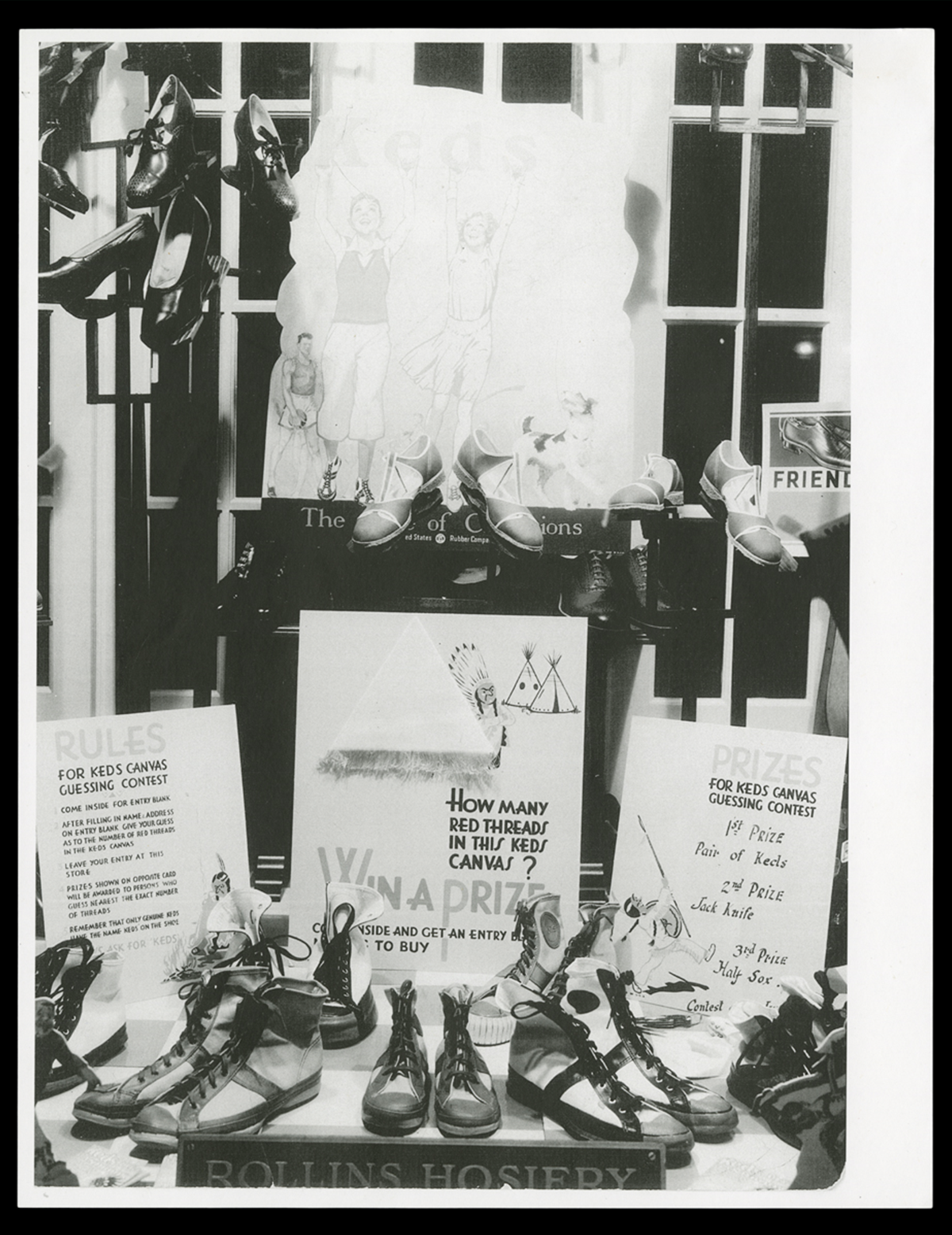

Additionally, kids loved fluoroscopes! Stores would advertise their shoe-fitting fluoroscopes alongside other child-friendly customer perks like balloons, contests, and candy.

Keds window display at the Campbell Boot Shop, Charlevoix, Michigan, circa 1930. This shoe store used window display contests to attract young customers with the possibility of brand new shoes. / THF723228

Until the late 1940s, fluoroscopes were used everywhere from first aid stations on job sites to quality control inspections on orange tree farms. However, the lack of regulation for radioactive machines endangered people. Several high-profile incidents eroded the public's trust in fluoroscopy. For example, between 1941 and 1943, 57 California Shipbuilding Corp. workers received mutilating radiation injuries after using the company's first aid fluoroscope. This lack of regulation also affected shoe fitting X-rays. A 1948 study of Detroit-area shoe stores showed that over 20% of stores' fluoroscopes produced 16 to 75 röntgens — the measure of radioactive discharge — per minute. At the time the maximum radiation exposure recommendation was .3 röntgen per week.

X-ray tube, circa 1915. Vacuum tubes like this are used to produce X-rays in fluoroscopes and other forms of radiography. / THF174376

In 1950, Carl Braestrup, senior physicist for New York City hospitals, was one of the first health officials to warn the public that shoe-fitting fluoroscopes could cause radiation burns and leukemia, especially in children. That same year, city health officers in Los Angeles reported that shoe-fitting fluoroscopy caused abnormal bone growth in children. But shoe stores were initially reluctant to get rid of their machines; Los Angeles shoe store owners claimed that parents' demand for X-rays drove them to keep them. It took until 1957 for Pennsylvania to become the first state to ban shoe-fitting fluoroscopes.

In many ways, the shoe X-ray represents a time when science and commerce seemed to go hand-in-hand but went toe-to-toe instead. Innovations, like the X-ray, were used to turn profits but also harmed the public.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope being photographed for digitization. / Photo by Staff of the Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The WASP: “An Airplane Knows No Sex”

During World War II, a groundbreaking group of American women defied expectations and gender bias to apply their skill in the air, flying over 60 million miles and 12,650 ferrying missions for their country during the war. Nearly 1,100 women volunteered as pilots with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). As WASP Bernice “Bee” Haydu said in a 2013 oral history interview for The National WWII Museum, “We showed the world that an airplane knows no sex.” Yet while they flew military aircraft for military purposes and risked their lives in doing so, they remained classified as civilian aviators and as such they received no military status, benefits, or recognition until decades later.

Even prior to the United States' entry into war, two pioneering pilots Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love were pushing for opportunities for American women in military aviation. They lobbied for inclusion and were bolstered by successful efforts abroad, where women were flying in support of the European Allies. Cochran and Love submitted independent proposals to the Army Air Forces for the noncombat employment of women. As a result, the two women were granted leadership of two programs — the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron led by Love and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment directed by Cochran. The momentum to use women pilots had some powerful advocates. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about the subject in her September 1, 1942, "My Day" column: “We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.” In August 1943, a year after the inception of the two, they were merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots under Cochran with Love in an executive role.

The WASP program took off. Trainees were based at Avenger Field near the small town of Sweetwater, Texas. A love of flying drew fierce competition for limited spots. Training on military aircraft was rigorous and difficult even for the experienced pilots accepted into the program. Unlike male fliers, who learned to fly as part of their training, the WASP trainees entered their program knowing how to fly. They were required to have completed 200 to 500 flight hours before being admitted to the program. Still, the washout rate hovered at just under 50 percent. Out of 25,000 applications received, 1,830 women were accepted and of those 1,074 completed their training.

Ruth Westheimer (2nd from left) and fellow trainees at Avenger Field. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.155

The 30-week training program at Sweetwater included 210 hours of flying time on a wide variety of military aircraft. The training culminated in a graduation where the pilots received their wings, often pinned on by Cochran herself. Whether the civilian graduates would receive wings like their military pilot counterparts was initially questioned by some. And Cochran personally funded the purchase of the insignia for the first seven graduating classes (43-1 through 43-7).

The WASP went on to their assignments, ferrying planes from factories to airbases, “test-hopping” planes that other pilots had flagged as unreliable, and even towing targets used to train anti-aircraft gunners.

Class 43-6 included 22-year-old Ruth Westheimer. Raised by German Jewish immigrant parents in Jackson, Michigan, Westheimer was fascinated by flying from a young age, watching planes at the airstrip near her home. After graduating from Jackson High School in 1939, she plotted her path to the skies and attended the Civilian Pilot Training Program while studying at Jackson Junior College. She took a job as a secretary at Montgomery Ward & Co. in Chicago until she jumped at the opportunity to fly. Accepted for WASP training in April 1943, Westheimer initially failed the required day-long physical exam due to insufficient lung capacity. Determined to fly, she recognized what was holding her back and brazenly demanded to be tested again after removing her brassiere. She passed and became part of Class 43-6. In Sweetwater, Westheimer flew a variety of planes, but her favorite was the AT-6 “Texan” training aircraft. Westheimer loved ferrying duty.

Ruth stands in the foreground with her trainee roommates at Avenger Field. Ruth’s caption reads, “This is half of our bay. The gal with the magazine and pigtails is Mac. Bernie is the other one. Both are kids.” / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.073

For a time, Westheimer was based not far from home, with the 3rd Ferrying Group at Romulus Army Air Field in Michigan. At the same time, Chinese American Hazel Ying Lee was also flying out of Romulus. Lee is a tragic example of the extreme risks inherent in the WASP’s work. Lee was later transferred to Texas for Pursuit School training. She died on November 25, 1944, two days after a collision while transporting a P-63 Kingcobra fighter aircraft. She was the last of 38 WASP who died in service.

Clipping from Ruth’s scrapbook showing Hazel Lee and her husband. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.237

February 1944 travel orders for Westheimer and Hazel Lee from Romulus to Montreal. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.244

During one of Westheimer's assignments, flying with a group from Montreal to New Jersey, the WASP ran into weather trouble. Navigating visually, she eventually found an airfield and was assisted in landing by military personnel. Westheimer later said, “You should’ve seen the surprise on their faces when they saw a 120-lb girl in uniform climb out of the cockpit of that large military plane.”

Ruth Westheimer steps out of a Fairchild PT-19A primary trainer aircraft at Avenger Field on May 6, 1943. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.017

WASP often carried out their missions in a hostile atmosphere. Despite the shared purpose of American victory, not everyone wanted the women to succeed. There was even some resentment from male pilots who wanted the women’s stateside jobs rather than overseas combat duty.

In March 1944, Cochran and Army Air Forces Commander General “Hap” Arnold presented a strong case for militarization of the WASP before Congress, but the push was unsuccessful. With the war in Europe won and the war in the Pacific winding down, the WASP militarization bill was defeated in the House of Representatives on June 21, 1944. With no active path to service, the WASP were dismissed and their program disbanded, finalized on December 20, 1944. The devastated women even had to pay for their own fares home. Some were able to get contract work with Air Transport Command or flying in other capacities, but many returned to prewar occupations or began new lives.

Ruth’s graduation announcement from Class 43-W-6. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.207

Ruth Westheimer moved to Boyne City, Michigan, with her husband, 10th Mountain Division Army veteran Marshall Neymark. They raised four children, and she worked at city hall as treasurer. Later in life, Ruth made her way back to flying. Her second marriage to Boyne city manager and pilot Forbes Tompkins returned her to the cockpit. She renewed her pilot's license and began to fly again in their Cessna. After Forbes retired, Ruth stepped into the position of city manager, the first time the position was ever held by a woman.

The WASP were finally recognized for their service in 1977, when they were retroactively granted veteran status. In 2009, a bill passed to award the Congressional Gold Medal to the WASP. At the U.S. Capitol ceremony in March 2010, Ruth was one of the 200 (out of 300 surviving) WASP present to receive her award. She considered herself a “Lucky Lady,” in the right place at the right time. Ruth passed away in 2016 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery — a right that would not have been afforded during the war.

This guest blog was written by Kimberly Guise, Senior Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs at The National WWII Museum, and Curator of Our War Too: Women in Service, currently on display at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation now through September 7.

The roof of The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation covers nearly 12 acres. A one-inch rainfall results in almost 326,000 gallons of water landing on that expansive roof.

Where does the runoff go?

The architect, Robert O. Derrick, and landscape designer, Jens Jensen, who planned the building and grounds, cloaked the infrastructure that managed that runoff deftly. The following article walks you through the route that the water takes as downspouts and pipes move it from the museum roof to a 2.5-acre pond behind the museum and on to the nearby River Rouge. Today the pond, out of sight to the public, plays a vital role in reducing the risk of flooding and silt buildup in the nearby River Rouge, and it enables the reuse of runoff to irrigate the grounds.

Pond located north of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and southeast of the Dearborn Transit Center (upper right). / Drone photograph courtesy of Bart Fraley.

The pond predated the 1929 founding of The Edison Institute.. It and another set of ponds to the west resulted from clay extraction by a local brickyard. The Ford Motor Company built a powerhouse next to the eastern most pond at the Ford Engineering Laboratory. This pond became the holding tank for runoff from the museum roof.

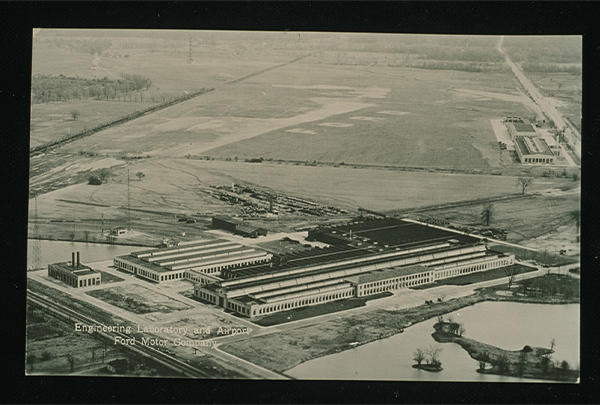

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Landscape architect Jens Jensen mapped “the pond” behind “the museum building” in December 1931. Moving water from the roof to the pond begins with downspouts embedded into museum walls and structural columns throughout the Great Hall. Because this flow enters the system above ground, gravity moves it into the drainage infrastructure under the museum.

Rainwater also flows into yard drains around the museum. Since the yard drains are below grade, the system needed pumping stations to collect and pump water vertically to send water up and into the roof-water collection system closer to ground level. Architect Robert O. Derrick incorporated two pumphouses into his museum plans in 1928 to house these pumping stations.

Derrick, noted for his Colonial-revival designs, disguised the pumping stations in reproductions of other structures popular during the Colonial-revival era. The inspiration included a garden feature from Mount Vernon, home of George and Martha Washington, and the observatory that astronomer David Rittenhouse built in Philadelphia after he moved there in 1770. Rittenhouse gained international attention in 1769 because of his observation of the transit of Venus. His relocation to Philadelphia in 1770, the largest city in the Colonies at the time, facilitated his engagement with the vibrant scientific community there. Contemporaries described his Philadelphia observatory as “a small but pretty convenient octagonal building, of brick” [William Barton, Memoirs of the Life of David Rittenhouse (1813), note 111].

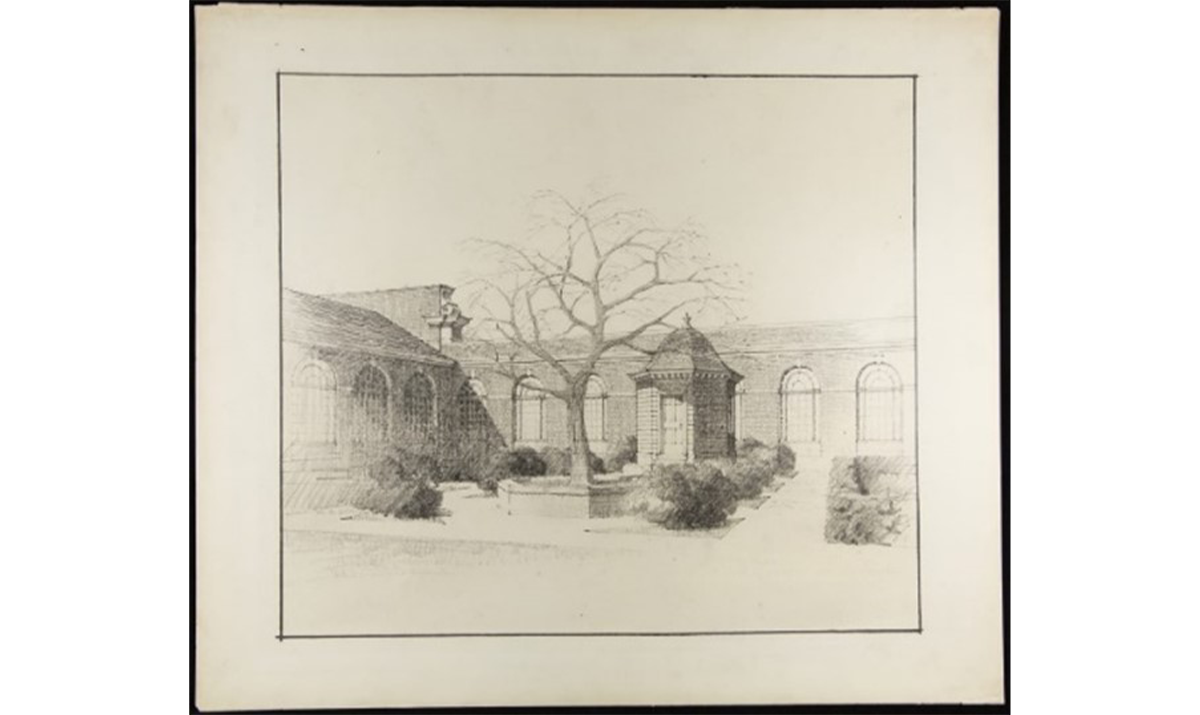

Virginia Court pumphouse based on a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

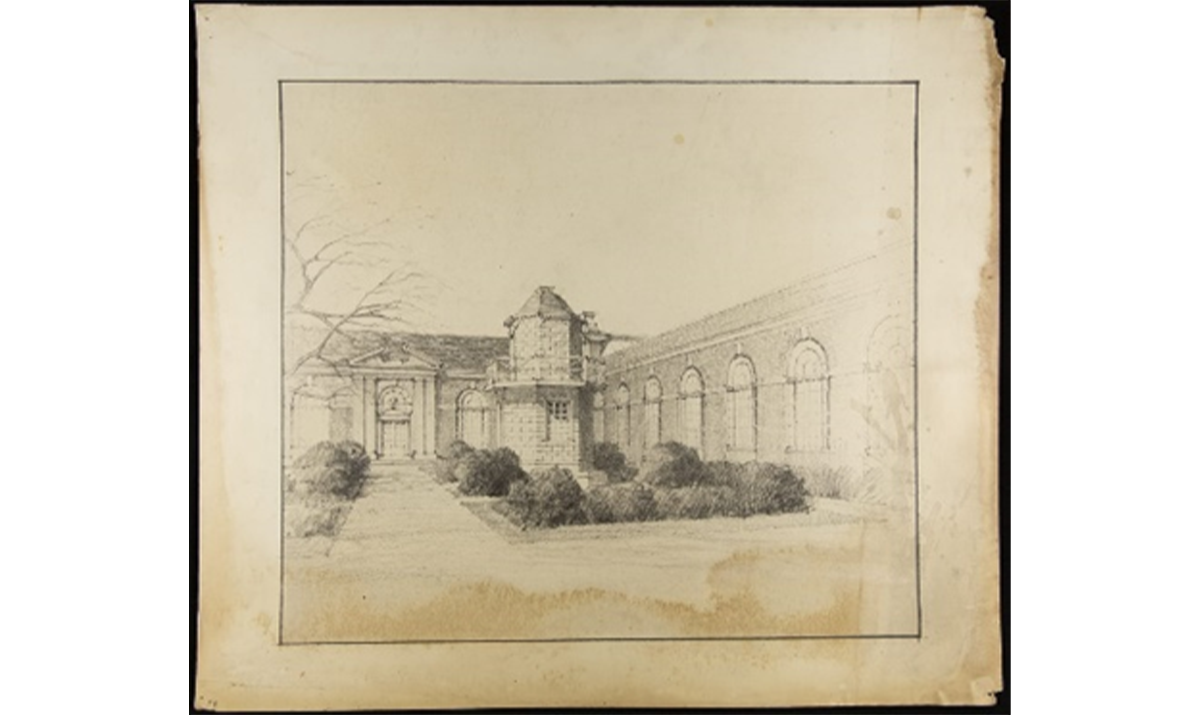

Pennsylvania Court pumphouse based on Rittenhouse’s observatory, 1928 / THF294392

The stations, located in each of the two large courtyards on each side of the main entrance to the museum, hold water and pump it into the stormwater infrastructure as needed.

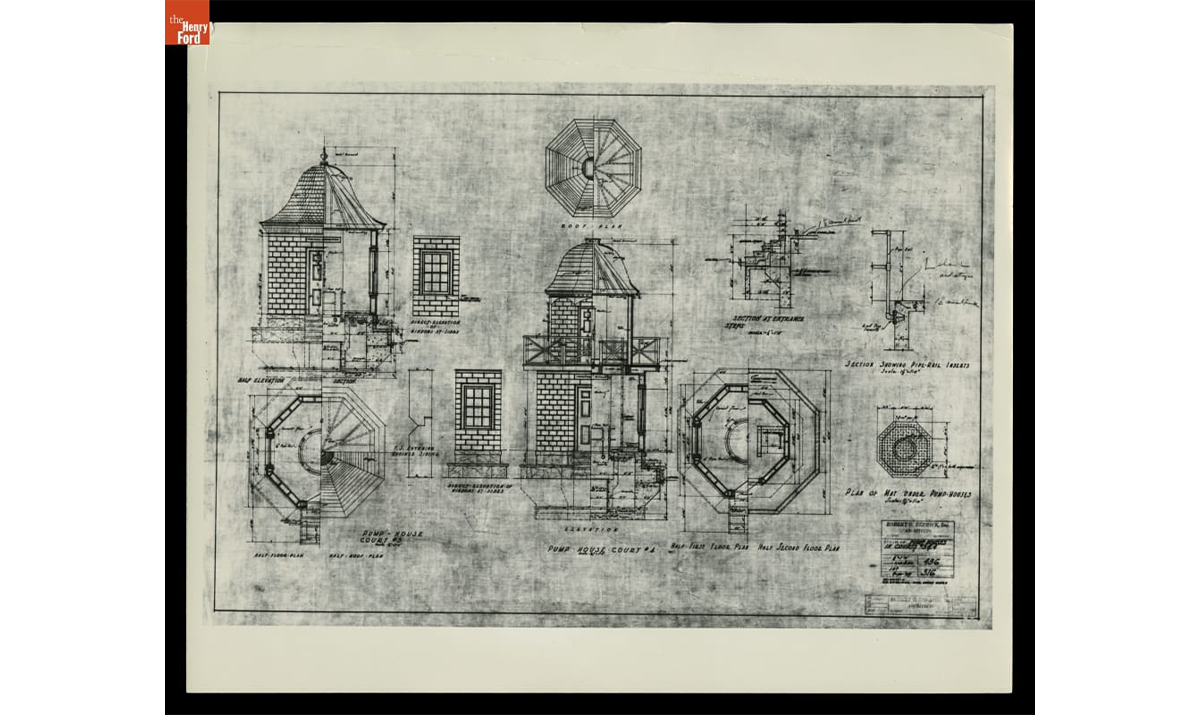

Details of pumphouses in museum courtyards, drawn by Robert O. Derrick, Inc., Architects, 1929 / THF98551

Gravity facilitates rainwater flow to a 24-inch main line under the museum, which channels runoff to the basement of the powerhouse in the back of the museum. Facilities staff replaced the entire ductile iron system in the powerhouse basement during 2025 with stainless steel. This was the first replacement since the entire system was built in 1929.

Storm-pump system in the powerhouse basement. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

Two 75-horsepower motors, located in the basement of the power house, handle large storms. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

In what's designed as a "wet" system, water always fills the lower portion of the infrastructure. As rainwater drainage increases the pressure in the system, it pushes water out of the museum and into the retention pond.

What happens after rainwater runoff enters the pond?

The retention pond allows sediment to settle out of the water within the pond rather than in the River Rouge. It also accumulates for later use to water the grounds around the museum, Lovett Hall, and the Josephine Ford Plaza. A large irrigation pump draws water from the pond to the irrigation piping.

The stormwater management system within Greenfield Village converges near the Suwanee dock and flows into the Suwanee Lagoon. The water in the lagoon is regulated by a drain that flows into the Oxbow which connects to the River Rouge. Facilities staff can use a pumping station at the Oxbow to increase the rate of pumping into the River Rouge in case of excessive rainfall. That pumping station also works as a protection. If the River Rouge is too high, a valve can be exercised to prevent backward flow into The Henry Ford's stormwater management system.

Each pond in the Village serves as a large holding tank with an inlet on one side and outlet on the other, depending on which direction the water needs to flow to reach the Suwanee.

Mill pond construction in the Greenfield Village craft area, March 2003 / THF10348

Mill pond in Greenfield Village’s craft area. / Photograph courtesy of Lee Cagle, May 2018.

Water within the system irrigates lawns and gardens within the Village. A large irrigation pump near Henry Ford Academy draws water from the Suwanee Lagoon for this purpose.

Overall, the water management system has been integral to The Henry Ford’s efforts to reduce waste and reuse runoff. An overview of five years of Green Museum Work undertaken from 2019 through 2024 acknowledges this system as one of the historic precedents and an inspiration for current efforts. It takes staff expertise, financial commitment, and regular maintenance to continue such efforts, but the investment pays off in reduced water bills and healthier riverine ecosystems. Updates to the system during 2025 should prepare it for the next 100 years.

Jon Bennett is Assistant Construction Manager and Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. The title of this blog was inspired by Al Green’s and Mabon “Teenie” Hodges 1974 song by the same title.

From Frames to Film at Ford Motor Company

Did you know that the Ford Motor Company was not only a pioneer in the automotive industry but also involved in the world of filmmaking? .

In the early years of the Ford Motor Company, various photographers and firms were hired to capture images, leading to the creation of the Ford Motor Company's Photographic Department. Their initial purpose was to document production methods, provide illustrations for publications, and promote Henry Ford and his company. This was the backbone that sparked another of Henry Ford's interests: filmmaking.

Henry Ford developed an interest in filmmaking in 1913 after he saw a film made by an external company about the Highland Park automobile factory. By April 1914, he instructed Ambrose B. Jewett from Ford’s Advertising Department to procure a camera and an operator. Within months, the company became established for their use of film in advertising, as documentation, and as a way to share industrial processes with the general public.

Ambrose B. Jewett of Ford Advertising Department is visible at center, with painter Irving Bacon (left) and Henry Ford (right), 1919. / THF95164

Henry Ford was fascinated by the potential of motion picture film to train workers and communicate daily news to the public, including scenes from their lives and the wonders of manufacturing at the Ford Motor Company. Starting with a modest two-man team in 1914, the Motion Picture Department expanded to 24 members, acquiring advanced 35mm cameras and establishing a film processing operation at the Highland Park Plant, comparable to Hollywood studios. By 1915, they began releasing news reels as “The Ford Animated Weekly.” Each episode covered a variety of current news events, such as the launch of the U.S.S. Arizona and the Liberty Bell on tour for the Panama-Pacific Exposition, in addition to animated segments.

The company's inaugural film, "How Henry Ford Makes One Thousand Cars a Day," naturally centered on its own processes. Initially, the department concentrated on current events and educational content; by the 1920s, it had shifted towards promoting popular themes like road quality, safety, and advanced farming techniques. As early as 1917, they recognized that film could assist in educating factory workers in their repair work by slowing down footage of fast-moving machines--a notion highlighted in an article from “The Ford Man” published on September 20, 1917.

Article from "The Ford Man" periodical, September 20, 1917 / Image by staff of The Henry Ford

The Ford Motor Company Photographic Department was responsible for both motion pictures and still photography, remaining the only department of its kind until 1918. It was initially housed in the administration building at the Highland Park Plant, moving to the administration building at the Rouge Plant in Dearborn, Michigan, in the mid-1920s. In 1956, it relocated again, this time to the World Headquarters on Michigan Avenue in Dearborn.

Workers at Cutting Tables and Copy Camera, Ford Photographic Department, Highland Park Plant, 1914. / THF124964

Initially, the department's photographers focused on documenting the company's products, facilities, and workforce. However, following the move to the Rouge Plant, the focus gradually shifted toward public relations and promotional activities. While few internal documents regarding the department's organization and management have survived, the negatives and photos preserved in the company's archives from the 1950s were ultimately donated to The Henry Ford in 1964. Notable photographers who worked for Ford Motor Company include George Ebling, Joseph Farkas, Michael Malley, E.S. Purrington, William Stettler, and C.E. Wagner.

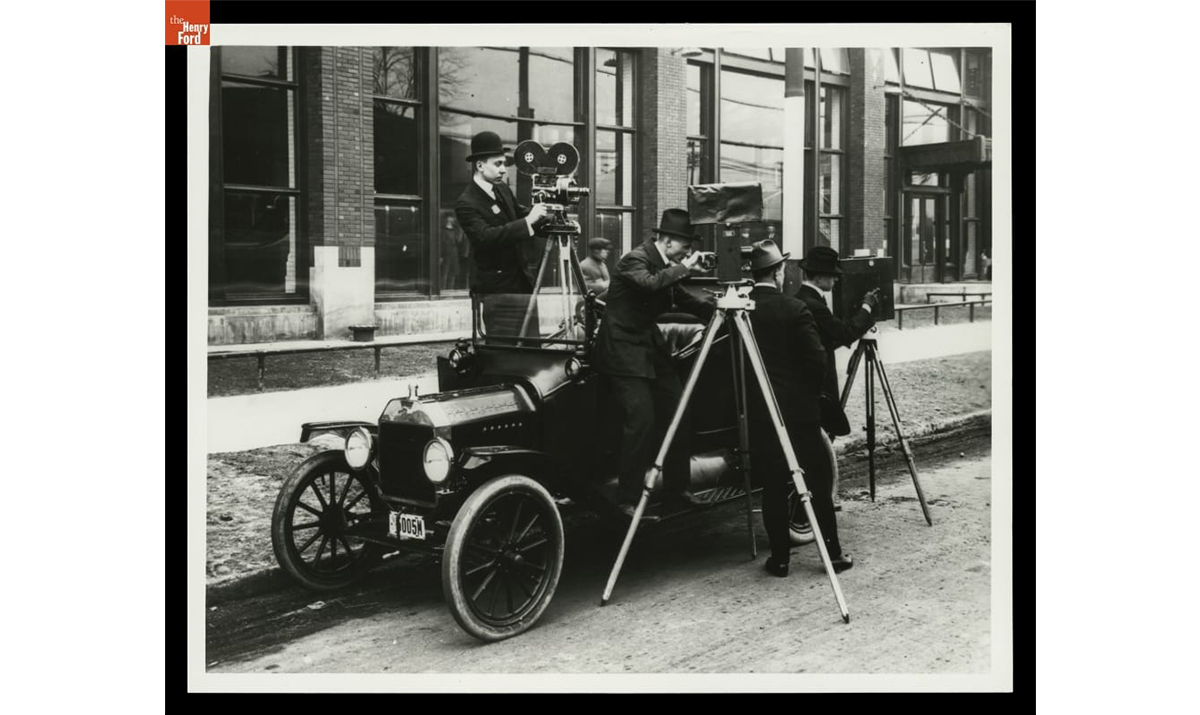

Ford Motor Company Photographers with Ford Model T Touring Car outside the Highland Park Plant. / THF119387

For years, the Ford Motor Company was one of the world's major film producers, with its films reaching audiences both nationally and internationally. These films were distributed through Ford branches to Ford agents, who then screened them in theaters within their respective territories.

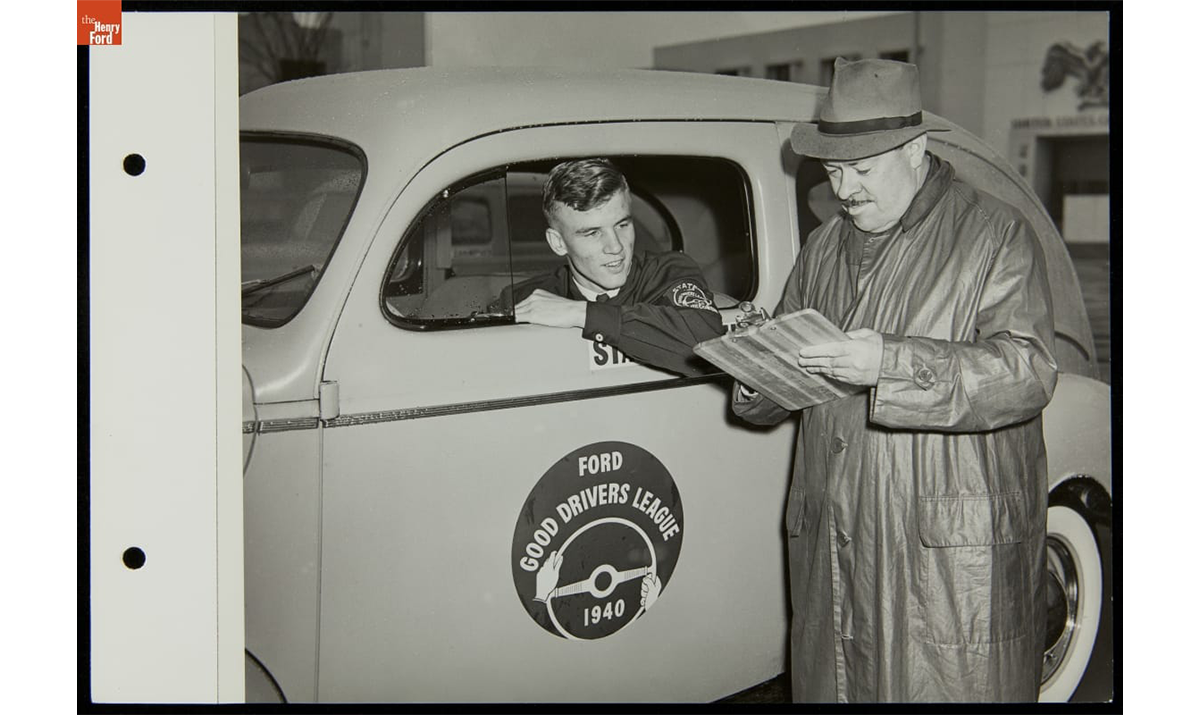

In 1956, Ford Public Relations films achieved a record audience of over 24 million viewers worldwide. The total audience for the year, excluding television, reached 24,267,455, reflecting significant growth in both domestic and international viewership. Throughout the 1950s, the types of films produced included categories like the Automobile Industry, Americans at Home, Vacation Films, Educational Subjects, and Driver Education Films.

Young Man Taking Driver's Test, Ford Good Drivers League, Ford Exposition, New York World's Fair, 1940. / THF216125

In 1963, Ford Motor Company gifted over 1.5 million feet of motion picture film, created between 1914 and the early 1940s by its Motion Picture Department, to the United States National Archives. The Ford Film Collection provides comprehensive coverage of the era's current events, educational topics, and special interests. The Henry Ford's Benson Ford Research Center secured permission on December 15, 1994, to reproduce and distribute high-resolution copies from the National Archives of those collections relevant to the early days of the Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford's personal endeavors, and subjects associated with The Henry Ford. The versions available in our online catalog and on YouTube are low-resolution samples with time codes, such as "Ford and the Century of Progress, Part 2."

The Ford Motor Company's journey from still photography to motion pictures is a testament to its innovative spirit and commitment to communication and education. By embracing filmmaking, Henry Ford not only documented the company's achievements but also shared the wonders of manufacturing and modern life with the world. Thankfully, Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company had such a passion and dedication to keep this work flowing, and it is now available for research. If you’d like to learn more about this collection or others, please email us at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Stephanie Lucas is a Research Specialist at The Henry Ford.

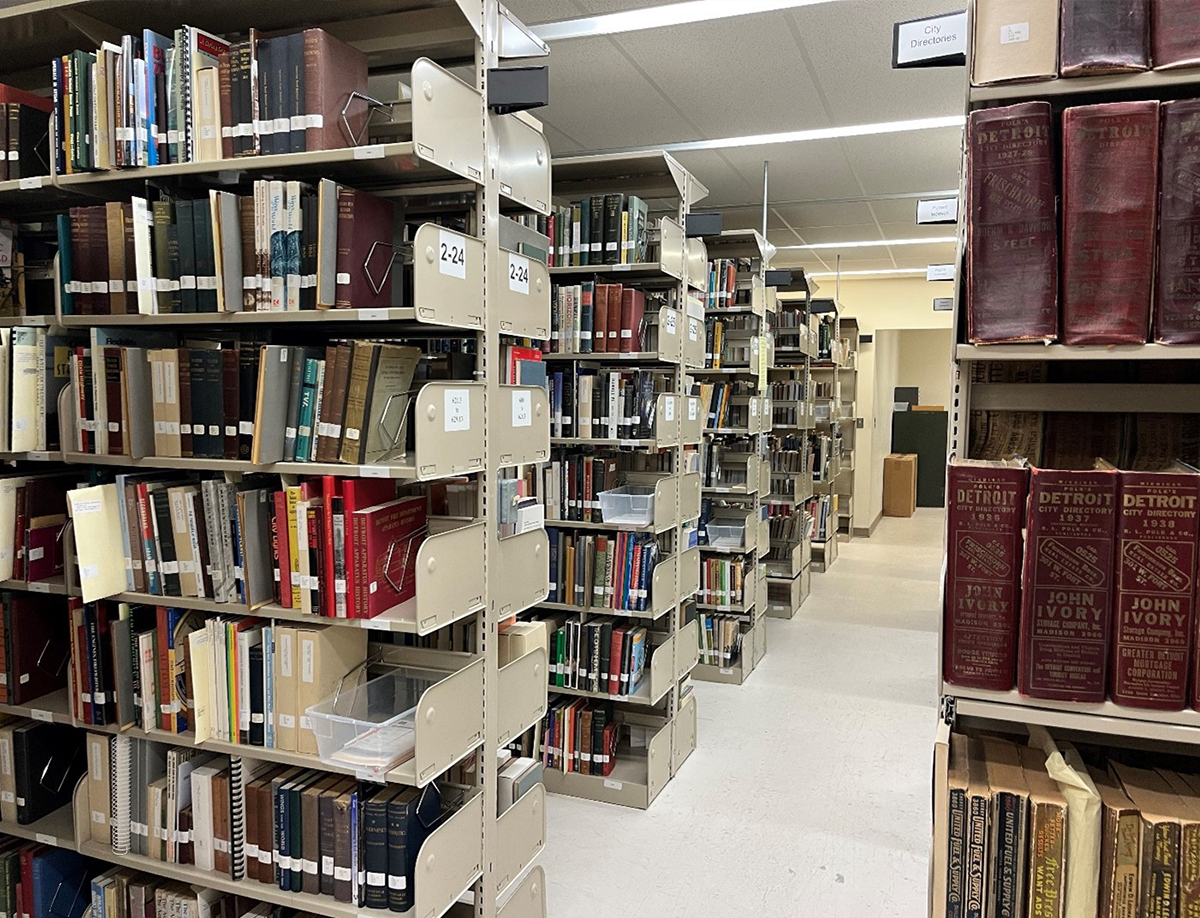

If you asked someone to picture a library, most would think of their local public library that presents the most recent, riveting, and relevant titles on their shelves. What they might not picture is the library here at The Henry Ford. Located in the Benson Ford Research Center — which you might have seen if you ever visited the Reading Room or parked across the street while in the back of the museum — is the Archives and Library collection at THF. The Henry Ford’s library is a little bit different from a public library because our team adds books to the collection based on their fit with THF’s mission and vision of American innovation!

The library stacks in the Benson Ford Research Center. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

One thing that the library collection at THF does have in common with a public library is that our staff are passionate about stewarding these collections for current and future learners. When it became clear that open shelving space for new books was decreasing, the library team decided they needed to act quickly. To begin addressing these space limitations, I joined the Archives and Library team as an intern to conduct a capacity study of the library collection’s storage.

During my internship, I calculated the total amount of space being taken up and the total amount of storage space available, and compared these numbers. Without a standardized system for measuring library storage or for assessing capacity I ran into some difficulties trying to get an accurate view of how full each shelf was. After some trial and error, I eventually adopted a system used by the Archives and Library staff to assess the capacity of the library storage along a scale of 0%, 25%, 50%, 75% to finally, 100%. These somewhat broad values allowed me to assess how full the shelves were, taking specific book storage best practices into account while measuring. As I embarked on this project, I found there were many unlabeled shelves and incomplete floor plans, which complicated how I collected data. After many weeks of measuring the total space available and assessing the capacity of each shelf, I found that the three floors of library storage are just over 70% full!

The archives in Benson Ford Research Center. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

Once I determined how much space was being taken up, I then needed to find the best solutions for addressing these all-too-common space constraints. After some research, I found that there were five potential solutions, each with its own level of applicability for the library collection. These solutions included:

- Shifting

- Deaccessioning

- Digitizing

- Installing compact shelving

- Renting off-site storage

Most of these options, despite being a good fit for libraries across the country, were not ideal for us at The Henry Ford. After assessing each solution in a rubric with categories, including collaboration, cost, efficacy, and time, I found that shifting and installing compact shelving were two of the best solutions. While neither of these are an immediate fix, they each provide opportunities to help our Archives and Libraries staff to steward the growing collection for generations of scholars to come!

Julia Noriega was a Ford Foundation Diversity and Inclusion Intern for Archives and Libraries at The Henry Ford

Dr. Sullivan Jackson: Saxophonist

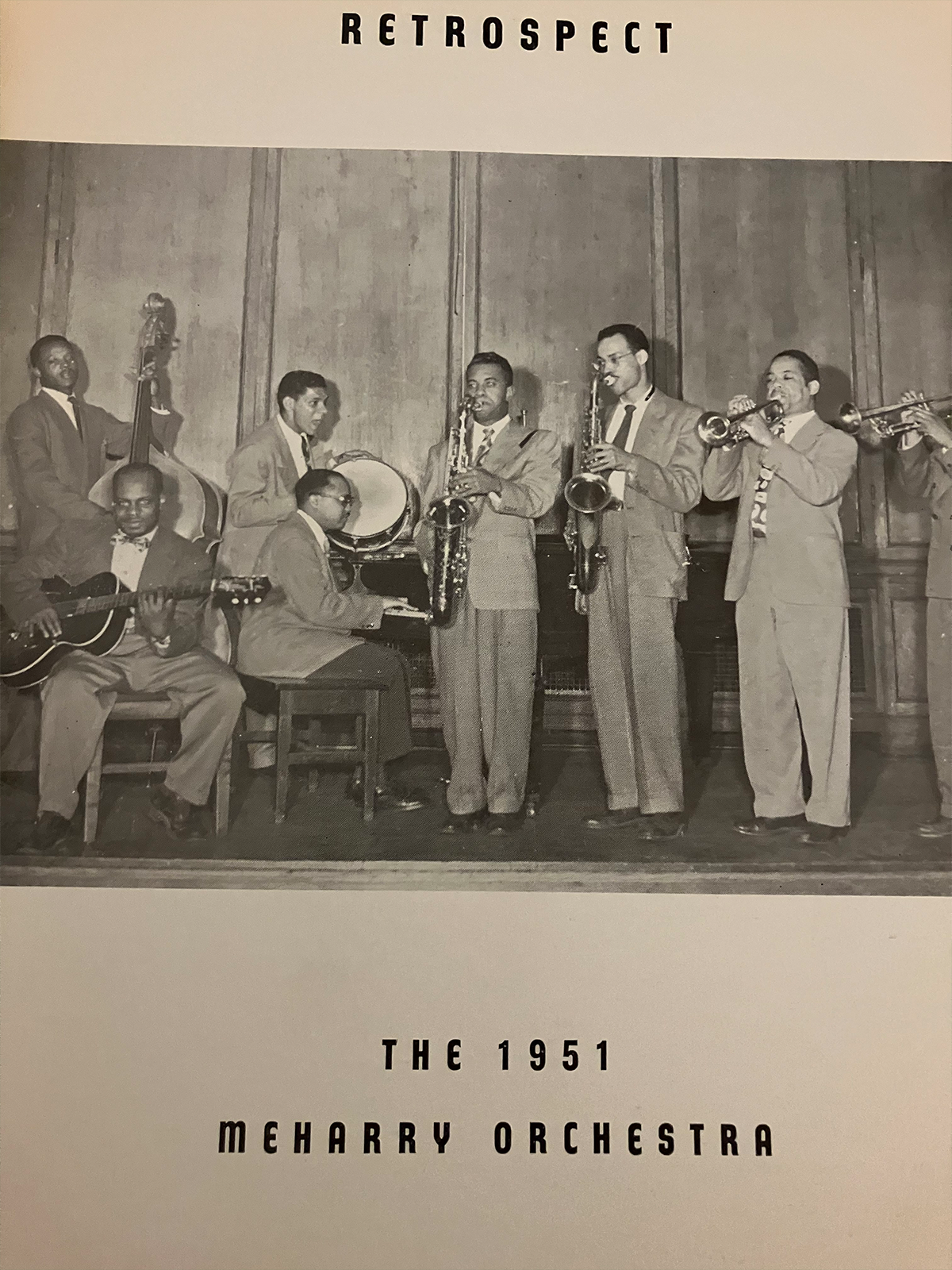

Music is a part of the Jackson family story, from the piano lessons that first brought young Richie Jean Sherrod soon-to-be-Jackson and young Coretta Scott soon-to-be-King together to the family's music room. In fact, Dr. Sullivan Jackson played tenor saxophone prior to his career as a dentist serving Selma's Black community. Dr. Jackson's time as a musician in the mid-1940s to the early 1950s allowed him to participate in Black American music cultural changes.

This picture of the Meharry Medical College Orchestra from the 1951 Meharrian yearbook shows Dr. Sullivan Jackson (center) playing the saxophone as a third-year medical student. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

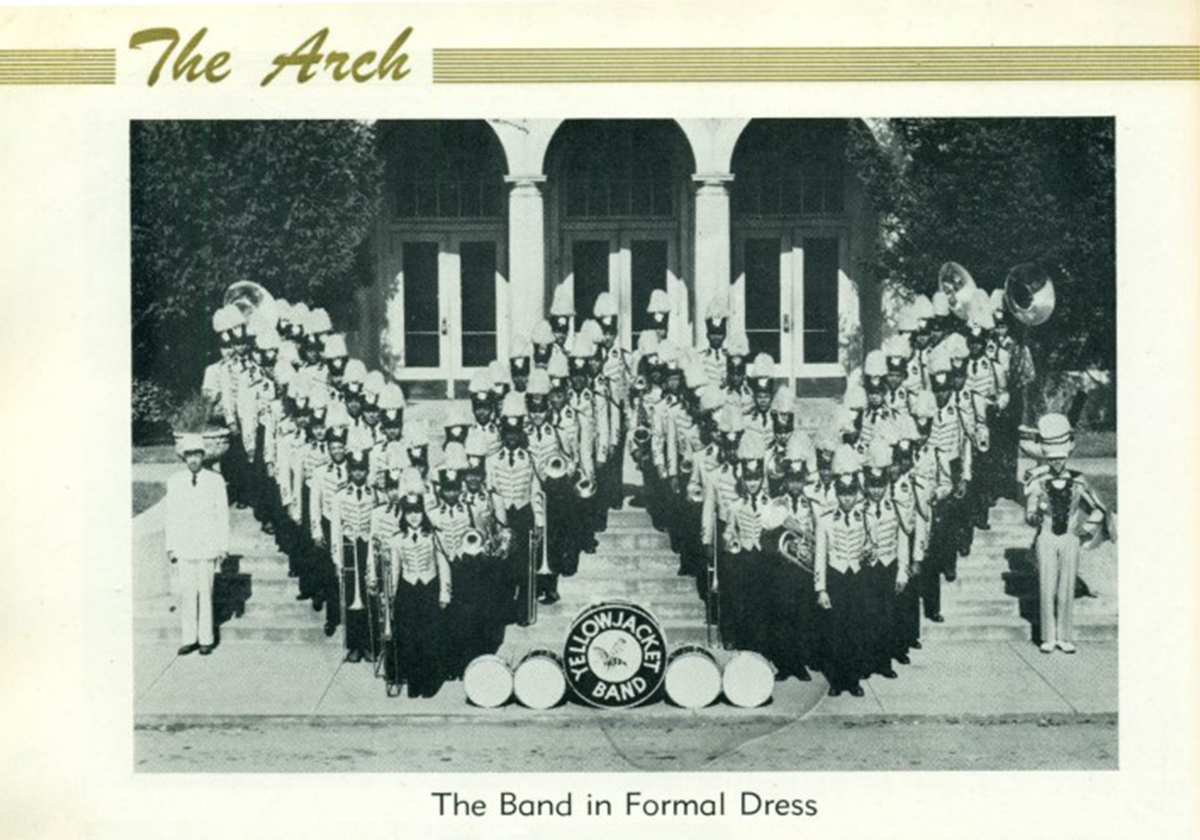

Following service in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, Sullivan Jackson enrolled at West Virginia State University (WVSU), one of 107 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). He joined the WVSU Yellow Jacket collegiate band as a saxophonist in the mid- to late1940s, a time when marching band culture at HBCUs was evolving.

Collegiate marching bands originate from U.S. military bands that played music to boost soldiers' morale and keep tempo during long marches. Starting in the 1840s, American colleges founded marching bands on their campuses and in the 1890s, Tuskegee Institute — now Tuskegee University — became the first HBCU to have a band. At most colleges marching bands were a part of Reserve Officers' Training Corps programs during this time. For example, Tuskegee's marching band was a part of the school's military science department — not the music department — prior to 1931.

Tuskegee Institute Football Pennant, 1920-1950. / THF157606

World War I changed the type of music that bands played at HBCUs. Between 1917 and 1918, the U.S. Army mobilized 27 new Black regiments, all of which established regimental bands. The approximately 1,000 Black musicians mustered out for service in these bands included collegiate conductors and music professors from HBCUs. While standard military marches were a part of the regimental bands' repertoires, they also played popular music such as Missouri-style ragtime and New Orleans-style jazz. After the end of the war, the veterans returned to their jobs at HBCUs and conducted collegiate bands to play both march music and popular songs as they had during the war.

This evolution reached a crescendo in the mid-1940s while the future-Dr. Jackson was at WVSU. In 1946, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College — now Florida A&M University — hired William P. Foster to direct the school's marching band. Foster recruited returning GIs, professional musicians and high school students to play in FAMU's band. Foster's musicians performed solely popular music, building on the legacy of Black regimental bands during World War I. They also marched in elaborately choreographed and physically demanding routines that played well in newsreels and later on television. Over the following years, other HBCU bands adopted Foster'sflair for pageantry and emphasis on contemporary music and choreographed spectacles. Even Dr. Jackson's own West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket marching band posed in a W-shaped formation in the school's 1948-49 yearbook, demonstrating this cultural change at HBCUs. This legacy remains the gold standard of band performance at HBCUs today.

West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket Band, circa 1948. / Via West Virginia State University Drain-Jordan Library

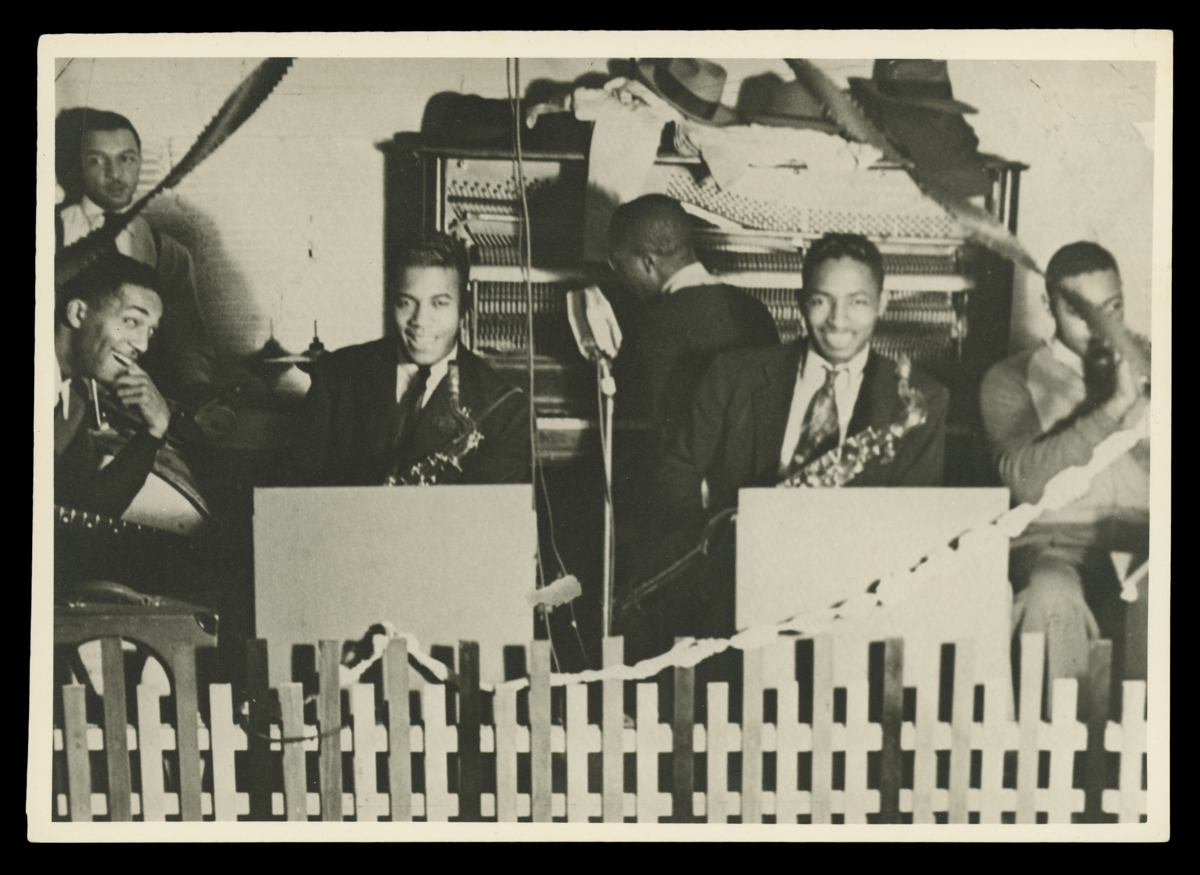

After graduating from WVSU, Sullivan Jackson pursued a degree in dentistry from Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. During that time, Dr. Jackson played saxophone in a band called the Doctors of Rhythm. The Doctors of Rhythm toured in what became known as the Chitlin' Circuit.

Sullivan Jackson with His Band, Date Unknown. Sullivan Jackson is seated second from the left holding his saxophone. / THF719998

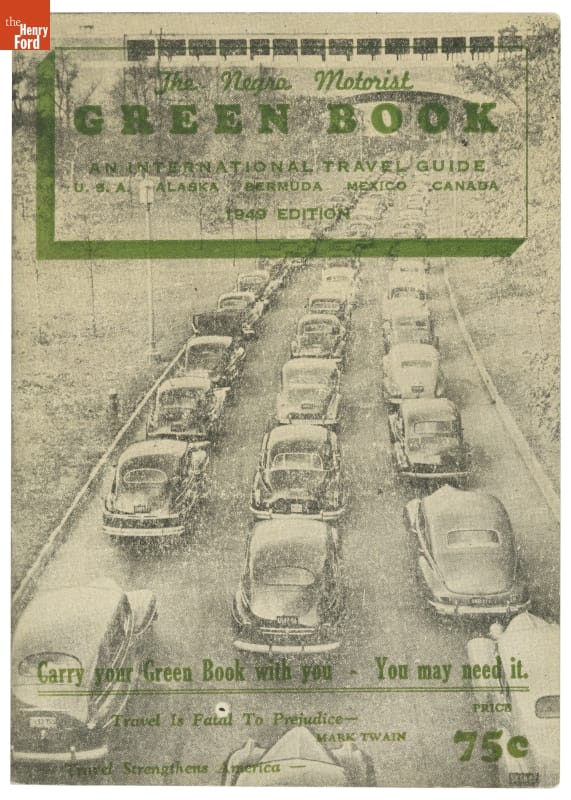

Exclusionary segregation practices in the United States meant that traveling Black entertainers could not go to certain venues. In the 1920s, the only booking agency that served Black musicians, comedians, dancers or singers was the Theater Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.). However, performers who were booked through T.O.B.A. paid their travel expenses out of pocket and could only play at White-owned T.O.B.A.-affiliated venues.

When the Theater Owners Booking Association folded due to financial collapse in the 1930s, an informal network of Black booking agents and venues for Black clientele arose in its place. Performers now had the freedom to play where they liked: from large theaters like the Apollo in Harlem to the hole-in-wall juke joints in small towns like Hobson City, Alabama. This network was later called the "Chitlin' Circuit." The name is a riff on "Borscht Belt" venues that primarily booked Jewish American entertainers for Jewish American audiences; it is also a reference to chitterlings, a controversial staple of Southern American cooking.

The Orioles Music Group inside Fox Brothers Clothier, Chicago, Illinois, 1942. The Orioles were a pioneering rhythm and blues group that performed on the Chitlin' Circuit in the 1940s and 1950s. / THF184199

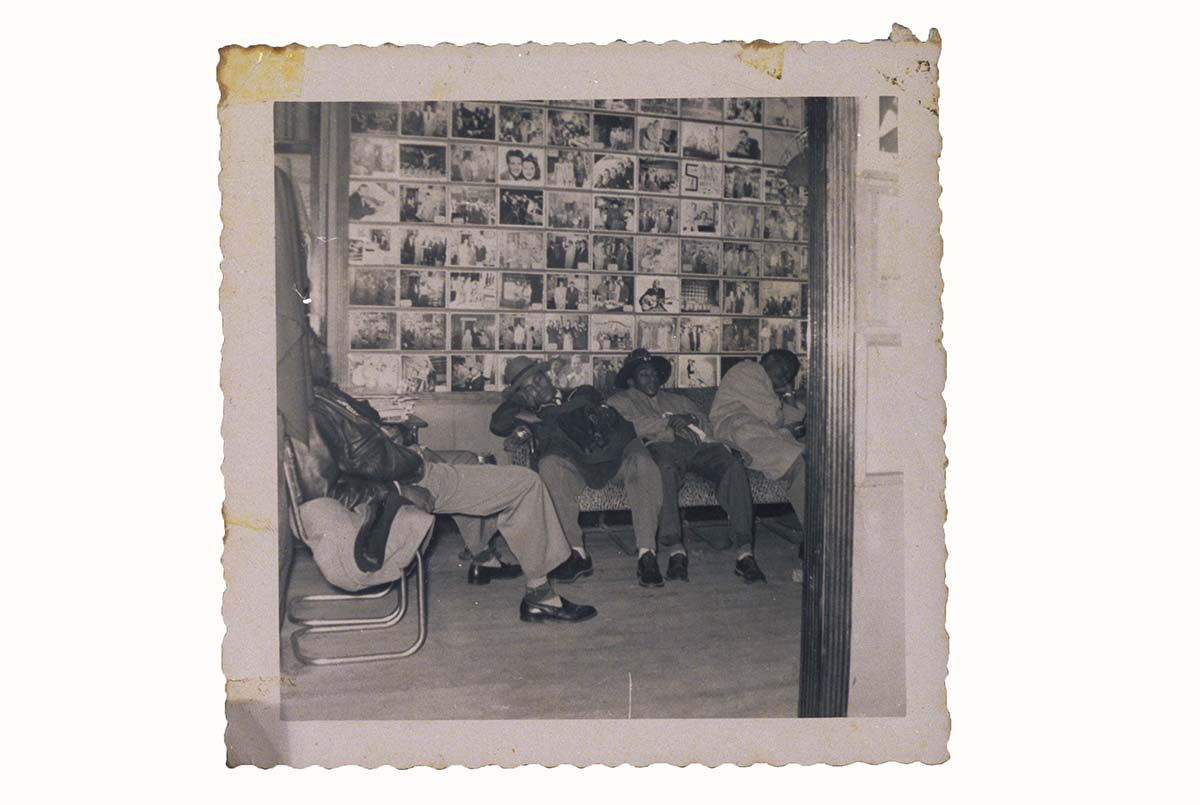

Performers like Sullivan Jackson appreciated the freedom afforded to them on the Chitlin' Circuit, but faced challenges on the road. Johnny Shines, a blues musician who toured the Circuit in the 1940s, described most venues as "rough" places where drinking, gambling, and fighting were common. Chitlin' Circuit audiences were notoriously harsh critics; the Apollo Theater emcee, "Sandman" Sims, used props like a hook or broom to kick acts off stage if the crowd booed them. Most venues paid the artists very little; sometimes payment came in the form of a hot meal instead of any money. Even traveling between shows could be perilous. Many Chitlin' Circuit performers had to drive all night to find safe lodging and were refused service while on the road. With Jim Crow laws in the South and thousands of sundown towns throughout the country, performers had to rely on resources such as the Negro Motorist Green Book and the hospitality from the communities they played in for travel, lodging, and food.

"Negro Motorist Green Book, An International Travel Guide," 1949. / THF77183

For a lucky few — like Chitlin' Circuit veterans Tina Turner, James Brown, Richard Pryor, or Jimi Hendrix — touring the Circuit was excellent training for their later famous careers. But even a short-lived entertainment career like Dr. Sullivan Jackson's provided Black performers with an opportunity to grow as artists and work within their own communities.

After graduating from Meharry Medical College, Dr. Sullivan Jackson became a dentist in Selma, Alabama, started his family and took part in the struggle for civil rights. But his connection to the music world was not severed. Among the Jackson family's many and frequent guests, traveling musicians — some of whom he played with — were also welcomed into the home. And Dr. Sullivan Jackson kept his tenor saxophone over the years and it is now part of the collection of The Henry Ford.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson's Selmer Mark VI Tenor Saxophone, 1968. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Molding the Future with Mold-A-Ramas

Visitors to The Henry Ford are likely familiar with the iconic Mold-A-Rama machines scattered throughout the museum. Loud, colorful, and with that distinctive “Mold-A-Rama” smell of warm plastic, they have spit out affordable souvenirs for thousands of guests over the years. The Henry Ford boasts 10 Mold-A-Rama machines, made more impressive when you consider only a few hundred machines were ever produced.

“Antique Automobile” Mold-A-Rama machine at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

Like all things at The Henry Ford, Mold-A-Rama machines are a story of classic American innovation. They were invented in the 1950s by John H. “Tike” Miller, after he sought to replace a broken figurine in his Nativity set. When he was unable to buy a single figurine from his local department store, he made his own from plaster. This would eventually lead to a business selling plaster figurines and then experiments with plastic injection molding machines. These advancements in molding machine technology would allow Miller to sell thousands of plastic figures out of his Illinois factory.

Final patent for John Miller’s plastic mold injection machine. / Courtesy of Google Patents

At the end of the 1950s Miller’s company declared bankruptcy, and Miller licensed the rights to his machine to Automatic Retailers of America Inc. ARA would go on to produce hundreds of Mold-A-Rama machines throughout the 1960s. Mold-A-Ramas were featured at both the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and the 1964 New York World’s Fair, and in 1966 they were installed at their first permanent location, the Brookfield Zoo (where they can still be found today!). After this, Mold-A-Ramas could be found in popular tourist destinations, restaurants, and even interstate rest stops. Experts estimate these golden years produced up to 300 unique moldsets for 200 machines.

Disaster struck soon after, when ARA elected to dissolve the Mold-A-Rama division of the business in 1968. The company cited high upkeep costs and excessive maintenance required as the reason for closure, a problem that continues today. By the 1970s, the original Mold-A-Rama Inc. had completely shut down.

When the company closed, both the Mold-A-Rama machines and operating locations were snapped up by various interested entrepreneurs. One such innovator was William A. Jones, a Michigan State graduate. Dissatisfied with his position as a corporate accountant, Jones purchased every Chicago area Mold-A-Rama machine and location from a retiring coworker in 1971. Ten years later, Jones would buy out a fellow operator to become the largest Mold-A-Rama company in the Midwest. In 2011, his company officially changed its name from The William A. Jones Co. to Mold-A-Rama Inc., marking the first time in 50 years that these machines were operated by their namesake. Today, Jones’s empire of wax spans seven locations across four states with nearly 60 machines.

Interestingly, the Mold-A-Rama machine has only one major competitor, the Mold-A-Matic. This story begins with store owner Eldin Irwin, who leased several Mold-A-Rama machines from ARA. When the company shut down production, Irwin purchased as much of the available inventory as he could and took the machines on the road. For years, he and his grandson would tour the country with the Mold-A-Ramas, visiting state fairs and carnivals. Like Jones, Irwin would expand his business dramatically in the 1980s. In this case, the Florida-based Mold-A-Matic Inc. wanted to sell their entire inventory, which Irwin acquired along with the name. Currently, the company is run by Irwin’s grandson and has 11 locations with nearly 50 Mold-A-Matic machines.

“1952 Weinermobile” Mold-A-Rama machine at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

In 2025, the dust has settled. While a handful of independently run Mold-A-Rama machines exist, Mold-A-Rama Inc. and Unique Souvenirs Inc. (formerly Mold-A-Matic Inc.) remain the only companies to service multiple locations. Both companies have remained in their respective families and are currently run by second- and third-generation Mold-A-Rama operators. The companies agree not to encroach on one another’s territories, and they even collaborate on occasion and share resources. This is especially necessary as the years pass and machines break down. Every Mold-A-Rama machine running today was built in the 1960s, and as time goes on, they become harder to repair—especially since their parts are out-of-production. Nearly 75 years after the Mold-A-Rama was first conceived, we are facing a future where it may fade out of existence.

Despite this, people’s love for the machines and their molds is still strong. Both Unique Souvenirs Inc. and Mold-A-Rama Inc. have websites providing information about the machines, their locations, and collectible molds. Griffin Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago recently hosted a temporary Mold-A-Rama exhibit, complete with additional machines and a rotation of retired molds. This exhibit was extended several times, and ultimately was so popular that it stayed on display for over two years.

Collection of current and retired molds at Griffin Museum of Science and Industry. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Display of a moldset and preliminary versions of the Mold-A-Rama at Griffin Museum of Science and Industry. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford

Outside of official channels, Mold-A-Rama fans share their experiences and collections on various social media platforms. It is truly impressive to see a machine that should have been made obsolete continue to thrive so many years later.

Rachael Monroe is Project Cataloging Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Assembled by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), this colorful backpack contains English and Spanish language versions of the book Borreguita and the Coyote, a VHS tape of a television episode centered around the book, and bilingual activity booklet and board game designed to let families practice their language skills together. This kit was likely given to a library, community center, or school for distribution, before eventually making its way into The Henry Ford’s collection in 2024. It represents an extension of the efforts to promote children’s literacy and love of reading undertaken by a program that would come to influence a generation of children: the Reading Rainbow television show.

Reading Rainbow "Borreguita and the Coyote" Family Literacy Kit, 1999-2008. / THF198380

First airing in 1983, Reading Rainbow was developed to address the problem of children losing their reading comprehension skills over the summer break. Hosted by LeVar Burton, each episode focused on a different topic related to a featured book, and consisted of live-action segments with Burton, a celebrity narrating the chosen book, and recommendations for similar books that viewers could check out at their local library.

In the show’s early days, television was viewed as the enemy to education, and the show creators encountered initial skepticism. Despite this, and thanks to funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, throughout its 23-season run Reading Rainbow demonstrated that it did, in fact, boost children’s reading skills. As the show progressed, it was able to tackle more difficult issues, with notable segments including footage of a live childbirth, and LeVar Burton talking to the students of PS 234 as they returned to their school after being forced to leave in the aftermath of 9/11.

Season 6 episode “Robbery at the Diamond Dog Diner” saw Peter Falk reading the picture book, of the same name and LeVar getting roped into working at a diner. This letter to “Dinerman” Richard Gutman, and other correspondence, indicates that he was helpful to the production team in their search for a diner to film in — a testament to the research the Rainbow team put into their live segments. / THF715225

Despite its immense popularity — the show would receive over 250 awards including a Peabody and 26 Emmys and earn the title of the most-watched PBS program in classrooms — Reading Rainbow faced new challenges with the 2002 passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, which shifted funding from programs that taught children to love to read, and toward programs that taught them how to read. The final original episode aired in 2006, although reruns would continue until 2009.

Like so many objects in The Henry Ford’s collection, this kit allows us to tell multiple stories. It allows us to talk about one type of literacy. It adds to our collections related to popular children’s television shows. It gets to the experience of immigrants in America as they try to learn another language. All of these are valid lenses through which to view this kit, and all were cited as reasons why it belonged in our collection.

At The Henry Ford, we share something common with Reading Rainbow — the belief that objects, like books, can expand our horizons through the stories they tell. But you don’t have to take our word for it!

To learn more about Reading Rainbow, check out the documentary Butterfly in the Sky. You can also find story segments from Reading Rainbow, along with related activities, on the Reading Rainbow website.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

When the United States entered World War II, there were immediate voids in the workforce left by those leaving to fight abroad. Women across the country heard a call to action and stepped in, taking on new roles previously held only by men.

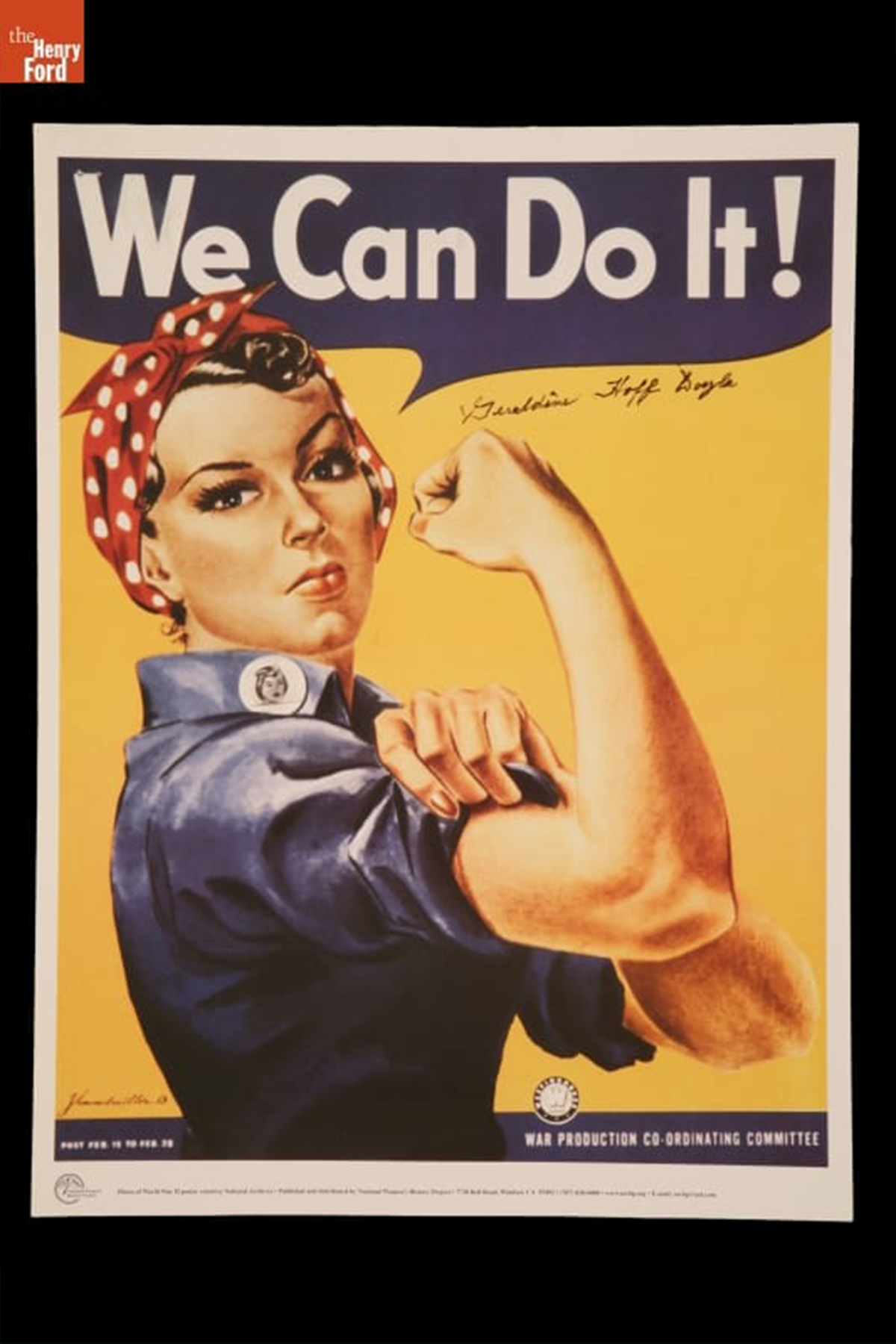

Popularized by the song Rosie the Riveter, Rosie became the fictional face of these early wartime women workers. Rosie was feminine, yet strong and powerful, changing the societal stigmas against working women and drawing interest in wartime work.

"Rosie the Riveter" sheet music, 1942. / THF290068

Reproduction World War II Poster, "We Can Do It!," 1998. / THF108519

Women across the country were inspired to join the ranks of Rosie but concerns over gender roles and domestic responsibilities discouraged others. However, as the war raged on and production needs continued to rise, the United States was faced with a manpower, or rather a womanpower, crisis.

Late in 1942, the War Manpower Commission announced a new campaign to recruit more women workers after estimating the majority of roughly five million new employees in 1943 would have to be women to keep up with war production demands. Ford Motor Company, placed at the center of the arsenal of democracy, was a leader in this campaign and shaping their facilities to attract more women to factory work.

Stories of real-life Rosies proved helpful in motivating others to find their place in Ford factories. These stories, documented by the Ford Motor Company Photographic Department, were distributed across the country to news publications large and small.

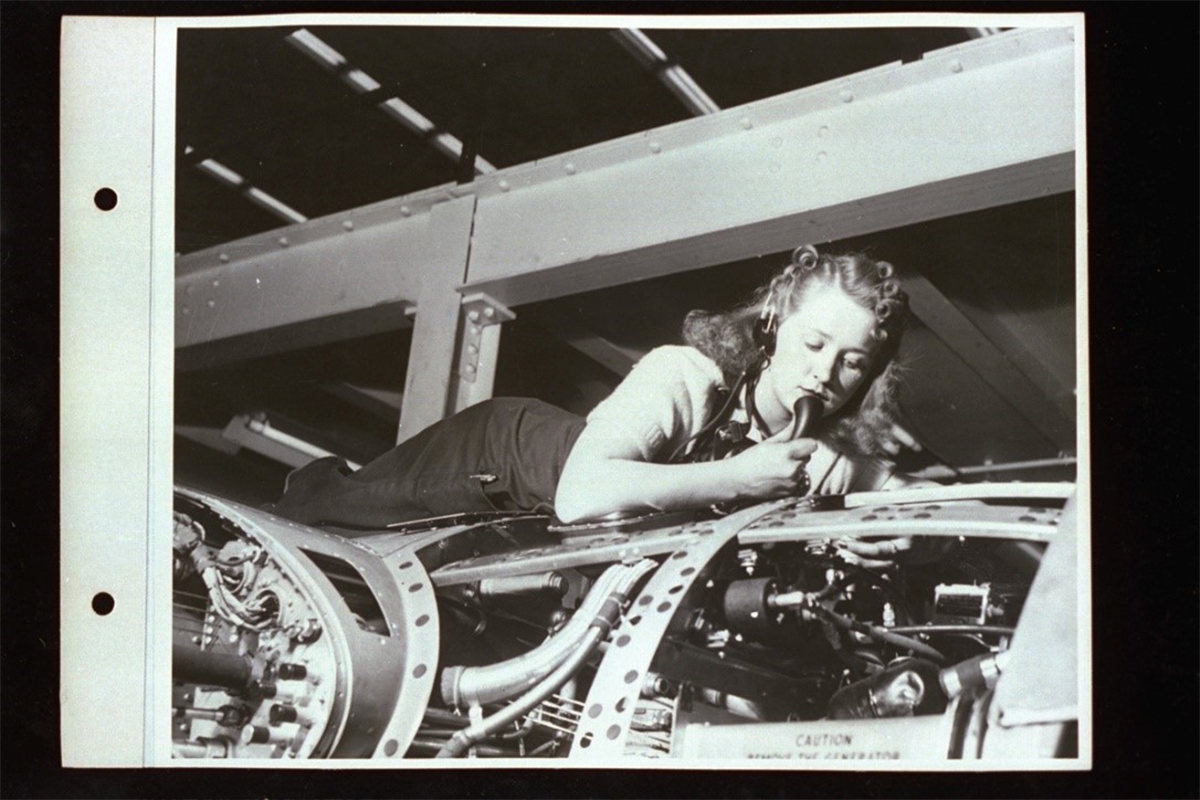

Riveter Florence Nightingale Working at Willow Run Bomber Plant, 1942. / THF93712

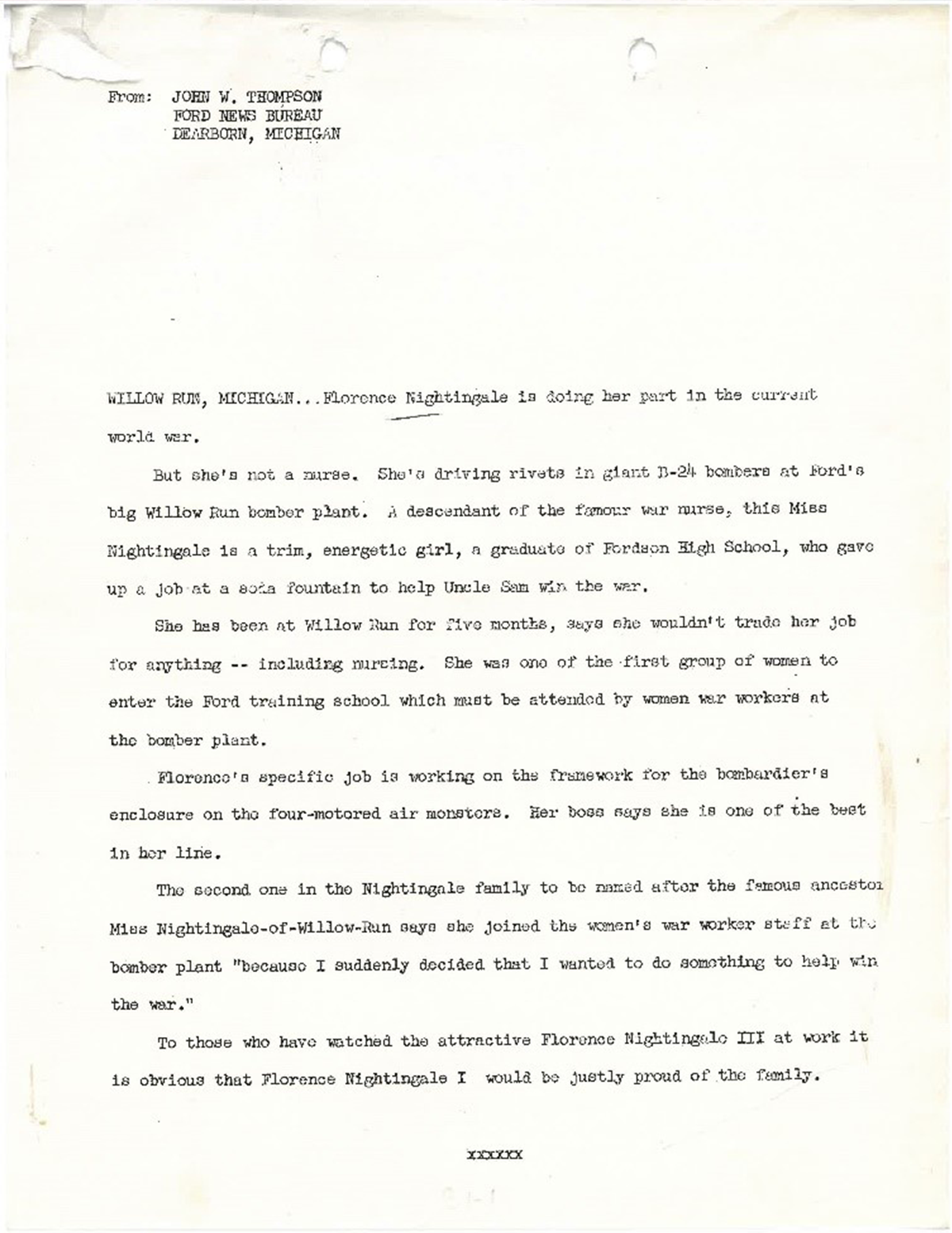

Florence Nightingale III Press Release, 1942. Accession 378, Box 30.

The story of Florence Nightingale III, descendant of the famous war nurse, was distributed locally and meant to recall the long-standing tradition of women’s contributions during wartime.

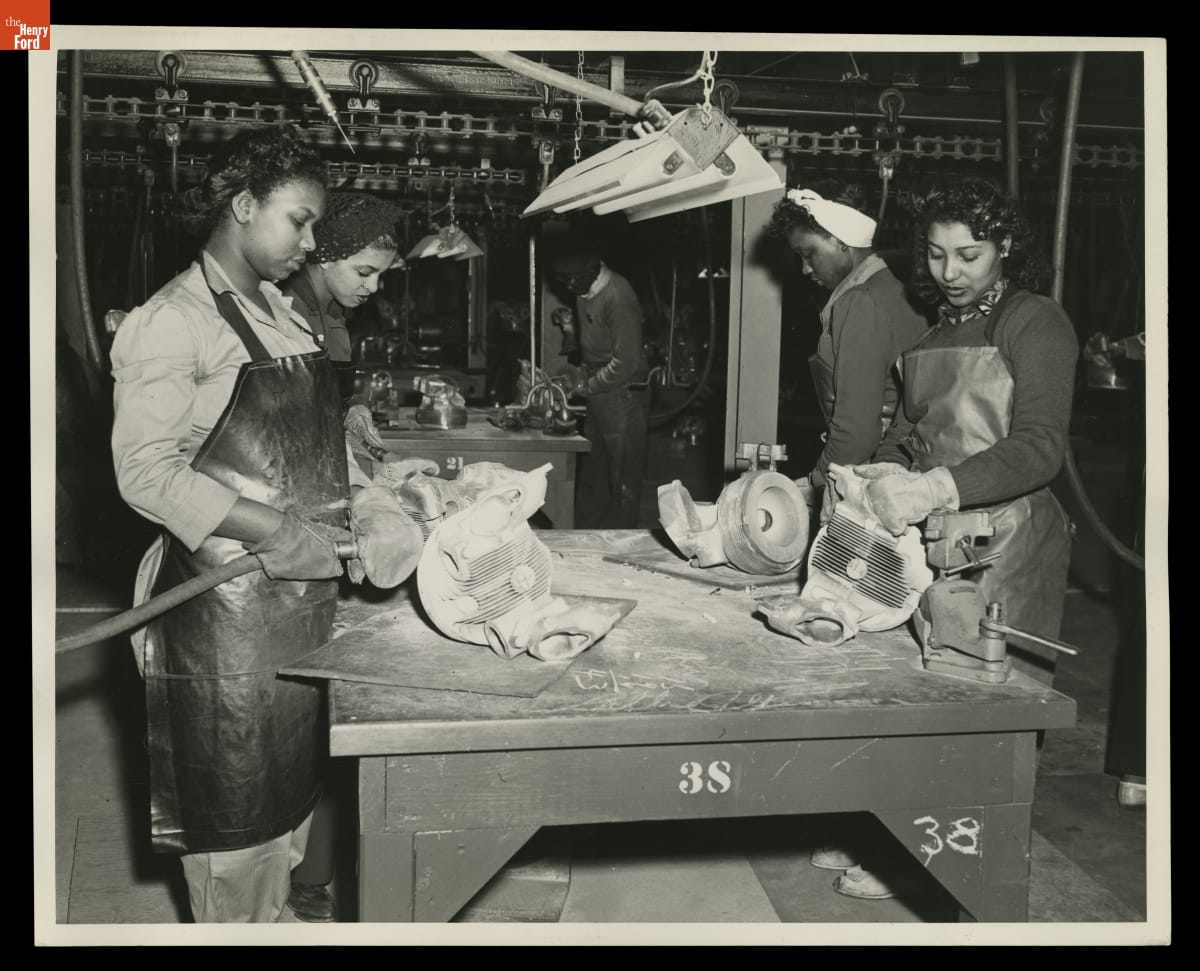

Women Making Sandcore Molds for Casting Cylinder Heads for Airplane Engines at the Ford Motor Company Rouge Plant, March 29, 1943. / THF82800

Women Making Sandcore Molds for Casting Pratt & Whitney Airplane Engine Cylinder Heads, Ford Rouge Plant, March 1943. / THF718497

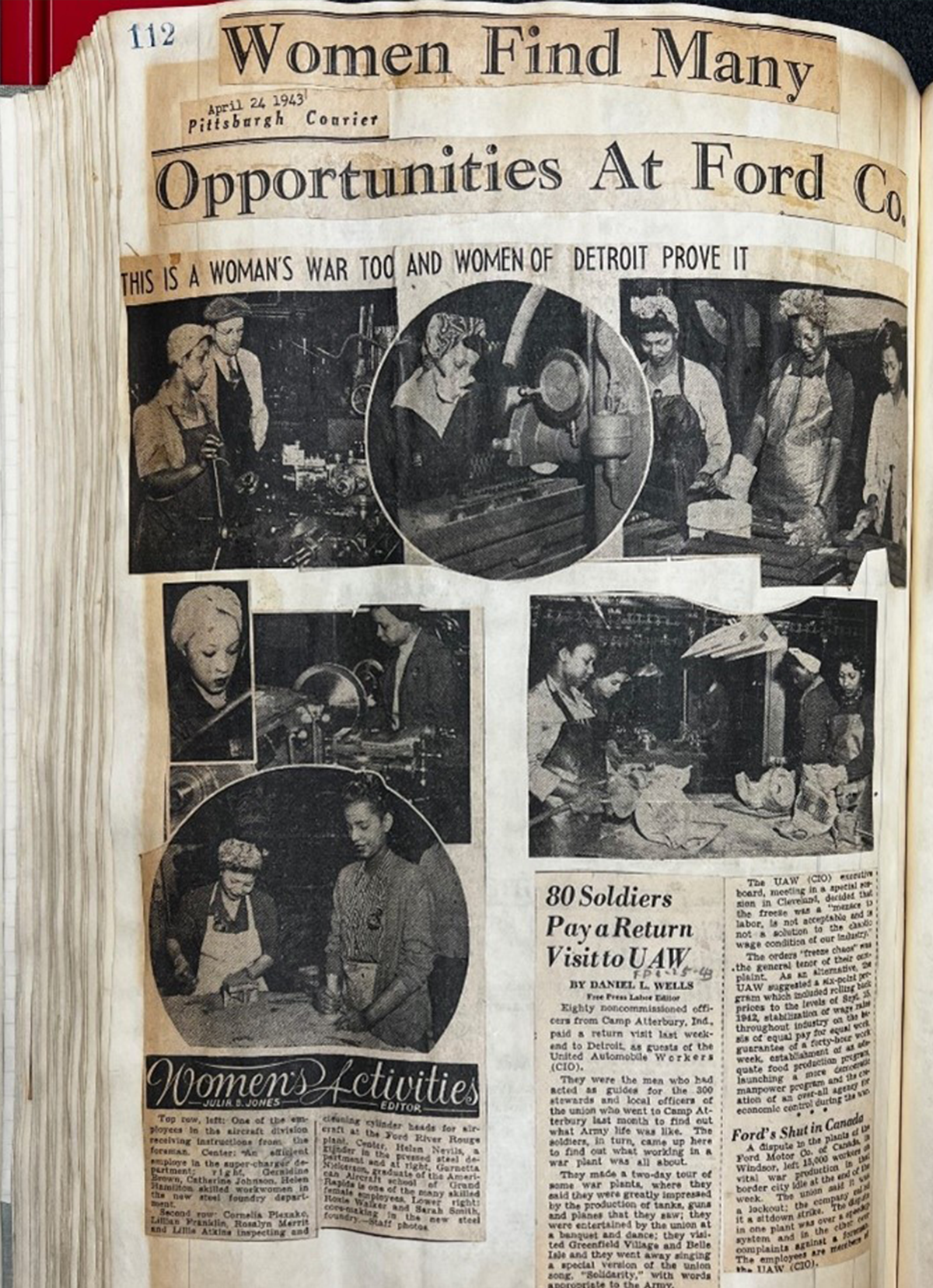

“Women Find Many Opportunities at Ford Co.,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 24, 1943. / Accession 7 Clipping Books Series, 1943.

A story on the women working at Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant was shared in the Pittsburgh Courier, highlighting the variety of jobs available to women and praising their skilled contributions to the war effort. Stories like this sought to encourage women to find work at Ford Motor Company and inspire efforts locally.

Norma Denton Using the Time Clock at Willow Run Bomber Plant, 1943. / THF23643

Norma Denton Atop an Airplane Assembly, February 1943. / THF326852

Norma Denton, a recent graduate, was featured in LOOK magazine, a popular and nationally distributed publication. Through a photo diary of her workday, part of a series titled Around the Clock Activities, Norma was photographed working, socializing, and enjoying the amenities of Ford Motor Company’s Willow Run plant. Her story aided in making wartime work more approachable and appealing to younger women.

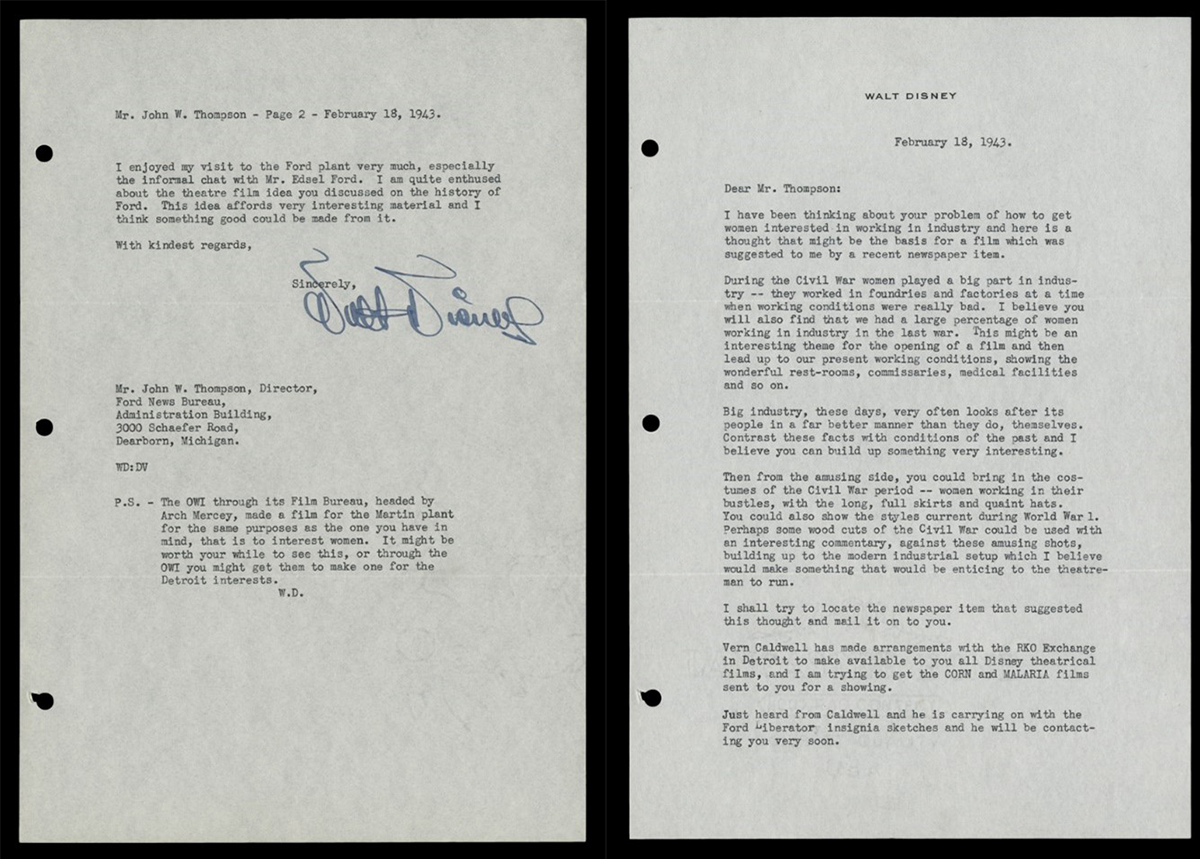

While these special features brought some success, workforce demands persisted and required other innovative ways to draw the number of women workers needed to win the war. Following a visit to Ford’s facilities — likely related to research for his own wartime films — Walt Disney offered some creative suggestions to aid recruitment.

On February 18, 1943, Walt Disney wrote to John W. Thompson, Director of the Ford News Bureau, regarding an idea for a “Womanpower” movie. In his letter, Disney proposed a potential film aimed at attracting women to the factories by emphasizing women’s past contributions during wartime and highlighting the amenities offered to a modern industrial woman. Disney notes how much he enjoyed his visit to the Ford plant and his informal chat with Edsel Ford.

Letter from Walt Disney regarding Making a Ford Motor Company War Work for Women Film, February 18, 1943. / THF131114, THF131115

Edsel seemed to agree with Disney’s suggestion. In a memo from March 1943, he notes that in addition to regular press releases and housing improvements for women employees, a film is in production highlighting women working at Willow Run on aircraft assembly.

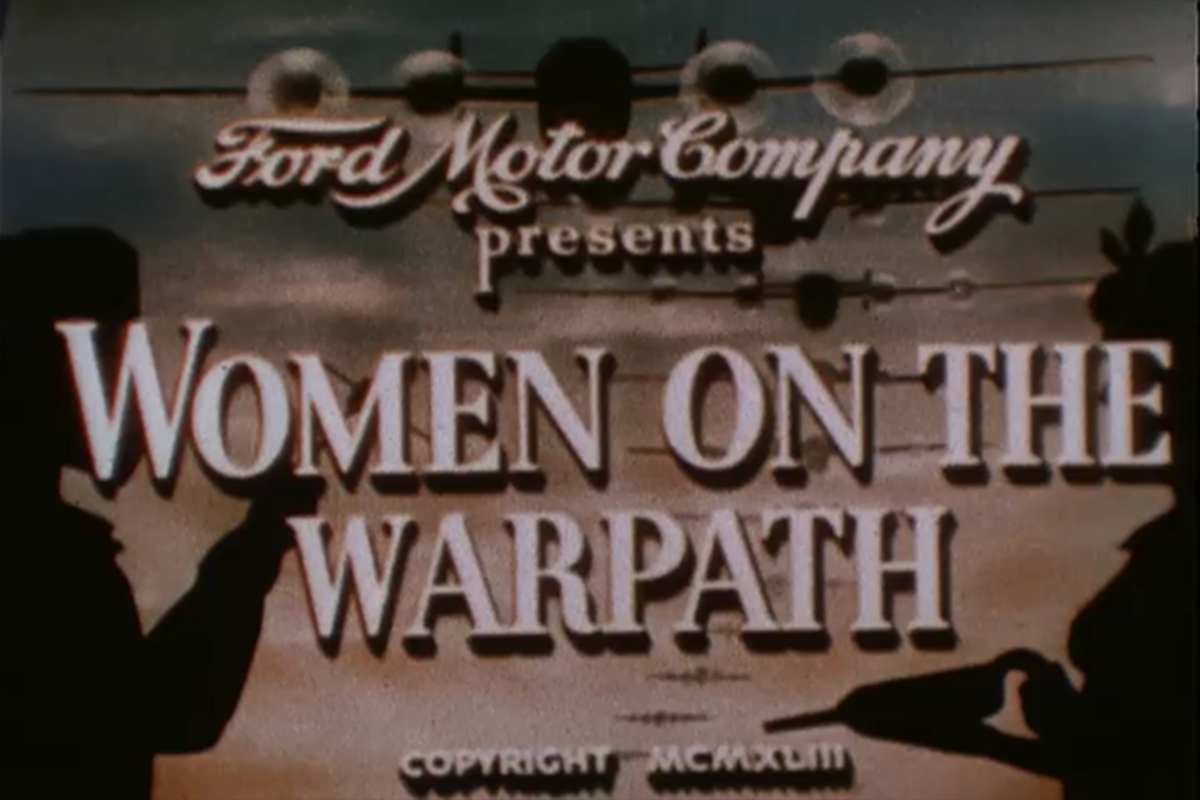

The ten-minute film, Women on the Warpath, aimed to inspire the next wave of women workers by recognizing the “American women everywhere, whose valor on the industrial front has sped the day of victory.” Previously, most women workers were young women or those who had traded traditional roles for higher paying factory jobs. The film makes an appeal to all women, including mothers and wives, that they are needed in the factories to help bring victory and their loved one's home. The film was distributed across the country with screenings in theaters and by a variety of women's clubs.

"Women on the Warpath," 1943. / Courtesy of the Ford Motor Company Collection and National Archives at College Park - Motion Pictures.

Ford Motor Company's efforts to recruit women workers proved victorious. During peak production, more than a third of their employees were women. As the war ended and men returned home to their jobs, many women returned to domestic roles seeing their work as a temporary patriotic contribution to help win the war. Others felt liberated from societal expectations and found a new sense of personal and economic freedom through working. It would take time before women represented a significant portion of the workforce in the same way, but the foundation had been laid for a more empowered and promising future.

Lauren Brady is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford