In June 1878, Eadweard Muybridge was hard at work. At the Palo Alto Stock Farm in Stanford, California, the photographer positioned 12 cameras along the side of a racetrack. A wire trailed away from each camera, connected to an electromagnetic circuit. Muybridge was meticulous; he wanted the experiment to work. Leland Stanford, once governor of California, commissioned Muybridge to answer a pressing question: When a horse ran, did all four hooves ever leave the ground?

It was a contentious topic among horse-racing enthusiasts, and Muybridge believed he could settle the matter using one of Stanford’s horses. Losing the horse onto the racetrack, as the animal careened around, it tripped the camera wires. Twelve tiny negatives were the result, capturing the full motion sequence. When Muybridge developed the images, they confirmed that when the horse gathered its legs beneath it, all four hooves left the ground.

Photographs from Muybridge’s series "The Horse in Motion." / Via Wikimedia Commons

Continue Reading

Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle: Enduring Kitchen Icons from Corning

Three brands developed by Corning Glass Works during the 20th century — Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle — became household names that revolutionized American kitchens and endured decades of changing consumer tastes and expectations.

Corning Glass Works found both industrial and household applications for Pyrex. The company produced Pyrex insulators and laboratory glassware alongside its increasingly popular ovenware in the 1930s. Pyrex Perfect Antenna Insulator, 1930-1939. / THF174626

In 1908, scientists at Corning developed glass that could withstand extreme temperatures. It was initially used for industrial products like railroad lanterns and battery jars. Hoping to broaden the market, Corning spent years testing possible household applications. Encouraged partly by the success of one notable experiment — when Bessie Littleton, whose husband was a Corning researcher, used a modified glass battery jar to bake a cake — Corning introduced Pyrex, a line of temperature-resistant glass cookware. The launch of Pyrex in 1915 inaugurated a new Corning division dedicated to consumer products.

This early advertisement for Pyrex ovenware touts its many advantages. National Geographic, 1916. / THF709296

Pyrex bakeware entered the market at an advantageous time. In the early 20th century, the principles of scientific management — used in industrial settings to improve efficiency — found their way into the kitchen. Transparent Pyrex ovenware fit the bill — it performed well, was easy to clean and could go from oven to table. The Pyrex line was expensive at first — marketed initially to women of means interested in up-to-date products.

Pyrex Flameware Percolator, 1939-1951. / THF191912

Pyrex’s excellent performance in baking was unquestionable. Yet, to become a greater contender in the cookware industry, Pyrex would need to be usable for top-of-stove cooking on an open flame. The introduction of Pyrex Flameware in 1936 added this feature, increasing the product’s appeal. Too, changes in manufacturing helped make Pyrex more affordable by the 1930s.

Corning Ware Casserole Dish, 1960-1961. / THF192899

Next up? The accidental discovery of a new material — glass-ceramic — by a Corning research chemist in 1952. The gleaming white opaque material could withstand extreme cold and heat and didn’t break when dropped. First used in nose cones for radar-guided missiles, this new material found its way into the kitchen in 1958 as Corning Ware — a line of innovative, shatterproof cookware that could go right from the freezer to the oven or range and then to the table as a serving dish.

Corning advertisement, 1968. / THF710401

Versatile, durable, attractive and affordable, Pyrex and Corning Ware became staples in American kitchens.

Color and More

Pyrex Primary Colors Mixing Bowl Set, 1949-1957 and three Pyrex Primary Colors Refrigerator Dishes with Lids, 1947-1960. / THF167736, THF176489, THF176490 and THF176488

By the late 1940s, Corning sought to appeal to evolving post-World War II tastes with a focus on the center of the American home — the kitchen. Continuing the trend toward enlivening kitchens with new products in vibrant choices, Corning transformed Pyrex from colorless to colorful with the “Primary Colors” line, introduced in 1947. Customers could mix and match sets of cookware that were practical and functional but also stylish.

Cornflower Pattern Percolator, Teapot and Platter 1960-1961. / THF370218, THF370237, THF191905

Corning applied a similar styling approach to its revolutionary Corning Ware line. The popular Cornflower Blue pattern, introduced in 1958, became synonymous with Corning’s brand identity. It appeared on all sorts of products — most famously on casseroles but also on percolators, teapots and platters. Consumers could buy pieces as needed and eventually collect a color-coordinated set of cooking and serving ware. Later patterns reflected new trends and helped broaden the market for Corning Ware.

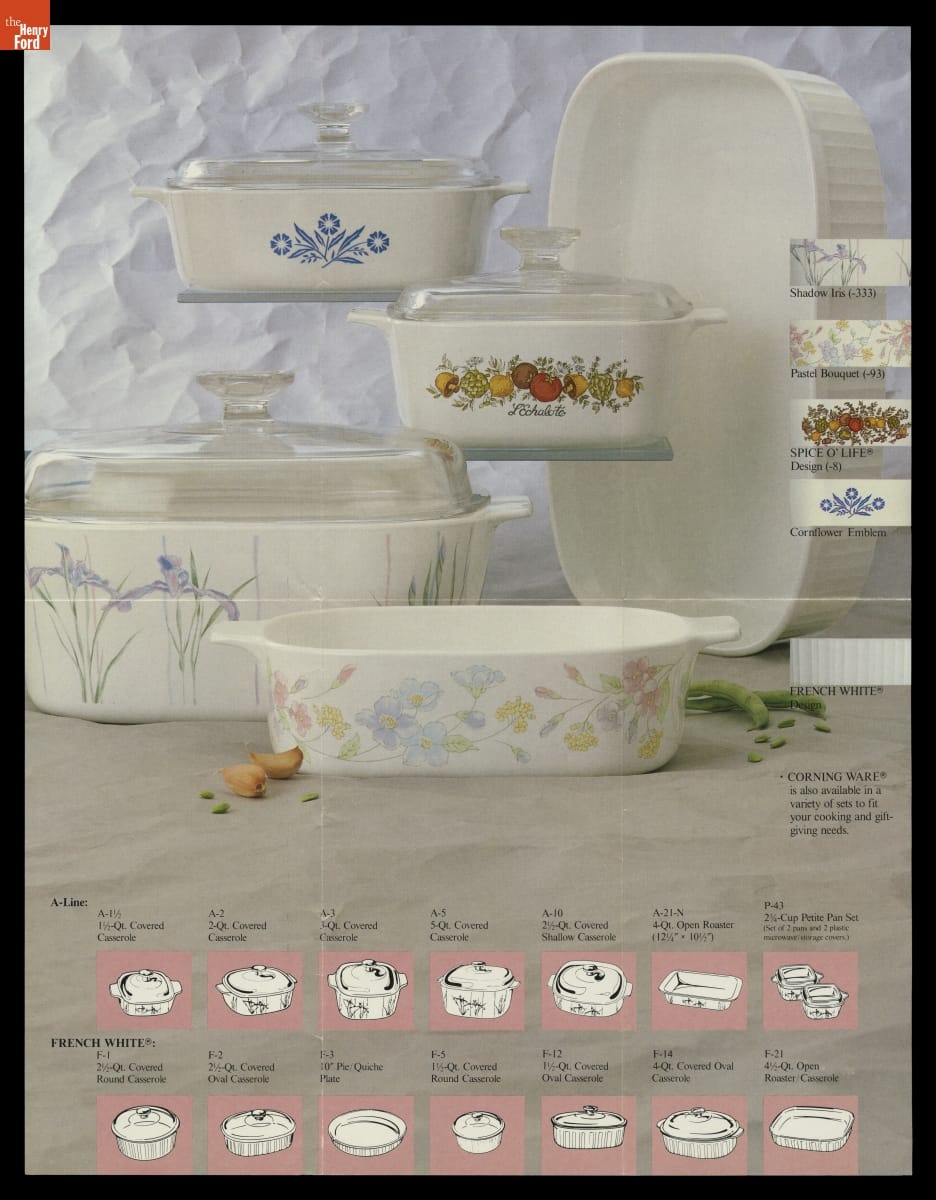

This Corning Ware brochure shows patterns available in 1987 — Shadow Iris, Pastel Bouquet, Spice O’ Life and the iconic Cornflower Emblem — as well as the now-classic French White line of casseroles. / THF709300

Revolutionizing the Dinner Table

Corelle Livingware cups and saucers in Butterfly Gold, 1971. / THF195008, THF195009, THF195011

Unlike Pyrex and Corning Ware — products made of new materials created without a singular purpose in mind — Corning deliberately pursued another kitchen innovation in the 1960s. The company thoroughly researched consumer preferences in dinnerware and then set to work on improving it. A breakthrough came in 1965 when a Corning scientist developed a laminating technique that produced very thin, yet very strong glass. Corning introduced Corelle Livingware, dinnerware made from this light and durable layered glass, in 1970.

Corelle Livingware dinnerware set in Spring Blossom Green, 1971. / THF195020

Corelle was a radical departure from the past, where expensive dinner sets consisted of many pieces, including luncheon plates and soup and salad bowls. By contrast, the first Corelle Livingware service consisted of a set of four large plates, four medium bowls, and four cups and saucers, retailing for the attractive price of $19.95. In addition, Corning provided a two-year guarantee to replace any piece that broke.

Corning’s savvy marketers compared Corelle to fine china. Product packaging with the slogan “looks, feels, and rings like china” depicted a mother “pinging” a Corelle plate. The company also offered consumers a selection of fashionable patterns. Pieces from the debut collection featured Butterfly Gold, Spring Blossom Green, Old Towne Blue and Snowflake Blue designs around the rim. Corning’s greens and golds were variations of the Harvest Gold and Avocado Green color schemes iconic of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Corelle was incredibly successful and changed middle-class American dining habits — it was chic yet durable and inexpensive enough for casual use. Corelle frequently sold out and was back-ordered throughout the 1970s. Corning continually added new “lifestyle” patterns and discontinued old ones to keep up with the latest decorative trends.

Still the Standard

Corning Pyrex FreshLock Plus food storage set with Microban antimicrobial product protection, 2022. / THF195359

Corning continually updated its Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle lines with new products that retained the qualities that had made them household names. The company sold its housewares division in 1998, but all three brands remained staples of American kitchens. In the 21st century, updated variations and marketing approaches appealed to changing tastes and lifestyle trends. Sets of Pyrex dishes designed for cold storage, portability and easy reheating featured locking plastic lids with odor-preventing technology. Marketers imagined new uses for classic Corning Ware, even designating some iconic French White casseroles as official companion pieces for the cult favorite Instant Pot brand of multicookers. (The company that manufactured Corning housewares merged with Instant Brands in 2019.) Continually updated Corelle patterns appealed to contemporary tastes.

Corelle Livingware dinnerware set in Northern Pines, 2022. / THF195362

Durable, convenient and stylish, the iconic brands developed by Corning in the 20th century continue to have relevance in today’s kitchens.

Charles Sable is curator of decorative arts, Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life and Saige Jedele is associate curator at The Henry Ford.

glass, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Charles Sable, 20th century

First Quarter IMLS Grant Update for 2023

To celebrate the completion of the first six months of work on our 2022-2024 IMLS Museums for America – Collections Stewardship Program, the Conservation staff are highlighting some standout objects we have cleaned and repaired. This grant began late last year as part of a two-year project to conserve, rehouse, relocate and create fully digital catalog records for 1,800 objects related to agriculture and the environment that have resided in the Collections Storage Building. Many of these objects will be used to support our Edible Education and Green Museum initiatives.

Stop by the back of the museum, near the steam engines, to get a peek through the windows of the Conservation lab and see what staff are currently conserving.

One of the first objects chosen for the grant was this entertaining dolphin-patterned culinary mold that received a thorough cleaning. The image above was taken during cleaning.

The inscription reads: “OF ALL Y FISHES IN Y SEA / I AM DOLPHIN EAT OF ME” / THF192318

This glass washboard was cracked in nine places and previously mended, but the glue was discolored from aging. The tin soap tray mounted in the wooden frame was corroded.

Continue Reading

Charley Harper’s unique approach to wildlife art — a style he called “minimal realism” — delighted popular audiences and earned the admiration of the scientific community. Best known for his simplified, geometric depictions of natural subjects (especially birds), his later work conveyed powerful messages about the environment. Harper credited early commissions from Ford Motor Company with encouraging both his focus on wildlife subjects and his signature style.

This updated take on a Grand Canyon landscape painted during Charley Harper’s honeymoon was the first in his “Horseless Carriage Adventures” series, which commemorated Ford Motor Company’s 50th anniversary in 1953. / THF706499

Beginnings

Charley Harper (1922-2007) began his career as a commercial artist in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the late 1940s. He’d just returned from a cross-country honeymoon funded by a traveling art scholarship. A portfolio Harper had assembled during the trip caught the attention of the Ford Times, a promotional magazine published by Ford Motor Company. Ford Times featured a mix of travelogues and general interest stories, with Ford advertising sprinkled throughout. Several pages near the back of each issue spotlighted noteworthy American restaurants. Charley Harper’s first Ford Times illustration appeared here, in the December 1948 issue.

Charley Harper’s first Ford commission was printed in the “Favorite Recipes of Famous Taverns” section of the December 1948 issue of Ford Times. / Detail, THF706474

Harper’s painting of the Gourmet Room, a restaurant atop the new Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati, was the first of many restaurant illustrations by Harper that appeared in Ford Times and its sister publication, Lincoln-Mercury Times. Some were later reprinted in a series of recipe books (of which Harper also illustrated two covers).

Continue ReadingRoald Amundsen Over the North Pole

Roald Amundsen, 1906. / Detail, THF621173

The list of Norwegian Roald Amundsen's polar accomplishments is impressive. From 1903 to 1906, Amundsen and a crew of six navigated the first ship through the famed Northwest Passage. In 1911, he became the first person to set foot at the South Pole. Following this history-making dash, Amundsen returned to the Arctic. In 1918, he set off to drive a ship into the polar ice cap and drift over the Arctic Ocean and perhaps the North Pole. The expedition ended in 1921 — unsuccessful. Though he failed, Amundsen and his crew joined the few people at the time to have traversed the Northeast Passage — the route along the Arctic coasts of Europe and Asia.

Continue Reading

1938 Massey-Harris Model 20 Self-Propelled Combine in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF110572

Combines loom large on the floor of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, but they loom even larger on the physical and historical landscape of America’s agricultural heartland. Standing high on the horizon, combines both symbolize and represent the reality of the mechanization of modern agriculture. The 1938 Massey-Harris Model 20 self-propelled combine, a designated landmark of American agricultural engineering, was the first commercially successful self-propelled combine to make its way through an American harvest.

1930s, 20th century, Henry Ford Museum, food, farms and farming, farming equipment, by Jim McCabe, agriculture

What Does a “Combine” Combine?

New Holland TR70 Axial Flow Combine, 1975. / THF57471

The combine — a piece of agricultural machinery — gets its name because it combines the three major tasks of harvesting grain:

- Harvesting: cutting and gathering the crop in the field.

- Threshing: removing the kernels or seeds of the crop from the rest of the plant.

- Separating: separating the kernels from other plant material such as stalks, chaff or straw.

Combines save large amounts of time and labor because they combine many activities into a single task. Self-propelled combines culminated 150 years of monumental changes in farming technology.

Efforts to perfect combine technology date to the early 1800s, but horse-drawn — and later tractor-drawn — machines were large and unwieldy. This combined harvester operated in California grain fields around 1900. / THF702847

Roast chicken. Mashed potatoes. A simple chocolate cake. Some foods have a sense of timelessness about them — they are reliable standbys that seem or stand the test of time with little to no alteration. Other foods, however, drift in and out of the public consciousness — and our refrigerators and stomachs. These foods are fads — practices followed for a time with exaggerated zeal, per the Merriam-Webster dictionary — and they reflect the values and preoccupations of the times in which they were popular.

As the 19th turned into the 20th century, domestic science and home economics arose as formally taught disciplines. Many domestic scientists espoused a view of women and women’s work that emphasized “feminine virtues” like beauty and daintiness. This changed the way women were expected to cook, as more emphasis was placed on presentation and nutritional value, rather than on creating culinary experiences that delighted the senses and filled the stomach.

This emphasis is readily apparent in the popularity of aspics — gelatinized dishes — in the first decades of the 20th century. Recipe booklets — most often produced by gelatin companies like Knox Gelatine and Jell-O — gave home cooks a myriad of ways to incorporate gelatin into their meals, in ways both savory and sweet. These dishes were often served on beds of iceberg lettuce, or in hollowed-out halves of fruit, providing a compact way of serving all of a meal's component parts in one tidy package.

The 1924 recipe booklet “Dainty Desserts for Dainty People” included recipes for jiggly jellied creations like "Salad-Dessert” and “Corned Tongue in Aspic.” / THF708085, THF708087

Aspics would remain a somewhat popular part of American cuisine into the 1970s, when they began to decline in popularity; some regional gelatin dishes hung on, though, and can be found at potlucks and family gatherings to this day.

While some food fads stem from the prevailing advice of the time, others stem from pop-culture trends of the moment. In the mid-20th century, American thoughts turned to space, and their appetites soon followed suit. Tang — the powdered vitamin C breakfast drink first produced in 1957 and marketed as a healthier, more convenient alternative to orange juice — rocketed to popularity after it was sent to space with John Glenn when he first orbited Earth in 1962. Tang’s subsequent marketing would lean heavily into the space connection, while continuing to tout its superior vitamin C levels and convenience. While its popularity in the U.S. waned in the years following the Space Race — despite being marketed as a potential ingredient in all sorts of recipes — it remains popular in Asia, South America, and the Middle East.

Advertisement for Tang, “Chosen for the Gemini Astronauts,” 1966 / THF230075

Less enduring in popularity after the Space Age were Space Food Sticks. These “non-frozen balanced energy snacks in rod form containing nutritionally balanced amounts of carbohydrate, fat and protein” (to quote the 1970 patent) were first produced by Pillsbury in 1969, and modeled after the food cubes the company had created for the 1962 Aurora 7 mission. They were marketed primarily to children, and had a consistency similar to a Tootsie Roll. Production halted in 1980, although for a period of time between 2006 and 2014, visitors to the Kennedy Space Center and the National Air and Space Museum could purchase a revival version produced by Retrofuture Products.

Pillsbury Space Food Sticks, 1969-1971 / THF175150

There have also been trends against certain foods. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) — first prepared in 1908 by Japanese chemist Dr. Kikunae Ikeda to achieve the distinctive, savory umami taste found in sea kelp — was first used by American food manufacturers in the late 1920s. In the wake of World War II, interest on the part of the military and the advent of frozen foods saw increased demand for MSG, and the first U.S. brand — Ac'cent — hit the shelves in 1947.

"Ac’cent: Crystals of 99+% Pure Monosodium Glutamate” Product Package, 1947-1955 / THF194339

The 1960s, however, brought with it a rising distrust of industrialized food, and MSG came under scrutiny — alleged to be the culprit behind everything from the vague “Chinese restaurant syndrome” to brain damage in mice. Despite questionable scientific evidence — the FDA has consistently classified it as safe for human consumption — MSG quickly fell out of public favor, although recent research into the science of umami has led to a resurgence in popularity.

Food fads can also be about how we eat. There has often been an element of prescriptive diet or health advice behind food fads, often tied to the idea of getting thinner as a synonym for getting healthier.

This introduction to “Sophia’s Recommended Recipes,” published by Weight Watchers in 1971, reflects the idea that being “lighter” is better, as well as the notion that diets are primarily for women (whom it assumes eat smaller portions), not men. / THF296150

“Fad dieting” has become its own term, often used to refer to trendy schemes that promise dramatic results, but have little to no scientific veracity. These trends come and go, with a new regime seeming to crop up every few years. Even the more long-standing weight loss programs change with the times, shifting their marketing and programming to best attract new clients.

1975’s “The Skinny Book,” published by Better Homes and Gardens and sponsored by diet soda brands TAB and Fanta, focused on low-calorie dieting as a method to weight-loss — with a healthy dose of product placement. / THF708069

The transitory and often contradictory nature of diet advice perhaps serves as a reminder that well-trained medical professionals — not marketers — remain an important resource for healthy eating guidelines.

Whether they stem from well-meaning advice or well-placed marketing, whether they are embraced or derided, food fads are an inescapable part of the culture of cuisine. Whether you dig into the latest dish or stick to the classics — bon appétit!

Rachel Yerke, associate curatorIn the early 1920s, Tsuneji "Thomas" Sato (1882-1969) found himself in the middle of a Michigan lumber camp on the opposite side of the world from his birthplace in Japan. Working with precision and productiveness and, most importantly, personality, Sato served a hot meal to a group of vagabonds who, although weary from their travels, had no apparent reason to be weary at all. Sato knew that firsthand, as he and his co-workers had been the ones responsible for getting this party — and their extravagant caravan — over hills, across rivers and through the wilderness.

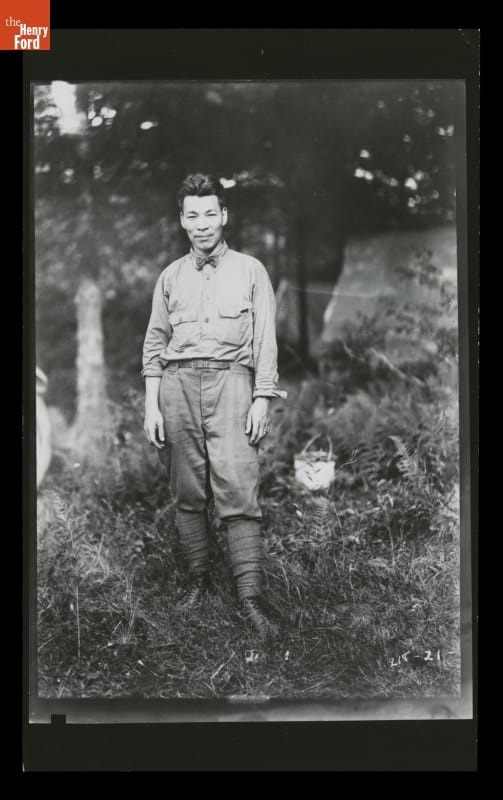

Tsuneji Sato, 1921. / THF127407

While the lumber camp was obscure, the camping party’s members certainly were not, as Sato’s employer was the man who needed the vast swaths of hardwood being extracted out of Michigan’s northern forests at this camp, and others, to feed his automobile manufacturing machine, Ford Motor Company. At the heart of the company’s brand recognition was the polarizing, do-it-yourself folk hero Henry Ford whose wealth contradicted his own populist ethos and whose life was wholly dependent on a group of people who made things happen for him. A group, for some time, that included Sato. So much so that Ford postponed this trip just to ensure that Sato could make it work around his own personal schedule.

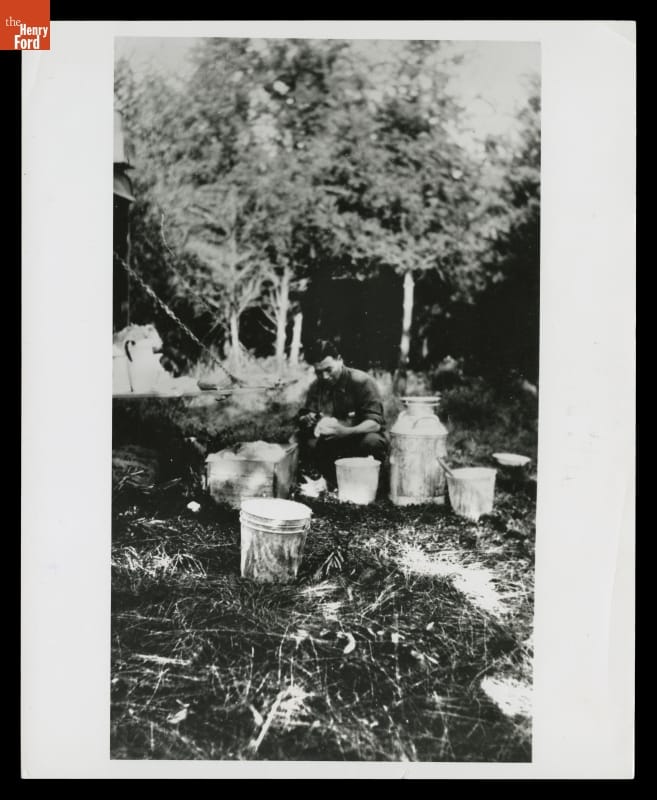

Tsuneji Sato preparing a meal at Sidnaw Lumber Camp in 1923. / THF127423

In some sense, the Fords were no different than other wealthy families of the early 20th century who had the means to staff their homes, preferring to hire domestic servants from a growing Japanese immigrant population generalized at the time as “polite, careful, clean, ambitious, and intelligent.” Japanese immigration to the United States had gradually increased over the late 1800s as the notoriously insular empire emerged from isolation and struggled with the abrupt pace of industrialization, regional war and a northern famine. By the early 1900s, hundreds, if not thousands, of Japanese immigrants were finding employment success in America’s household services sector, but a general spike in immigration began escalating a nativist angst among white Americans.

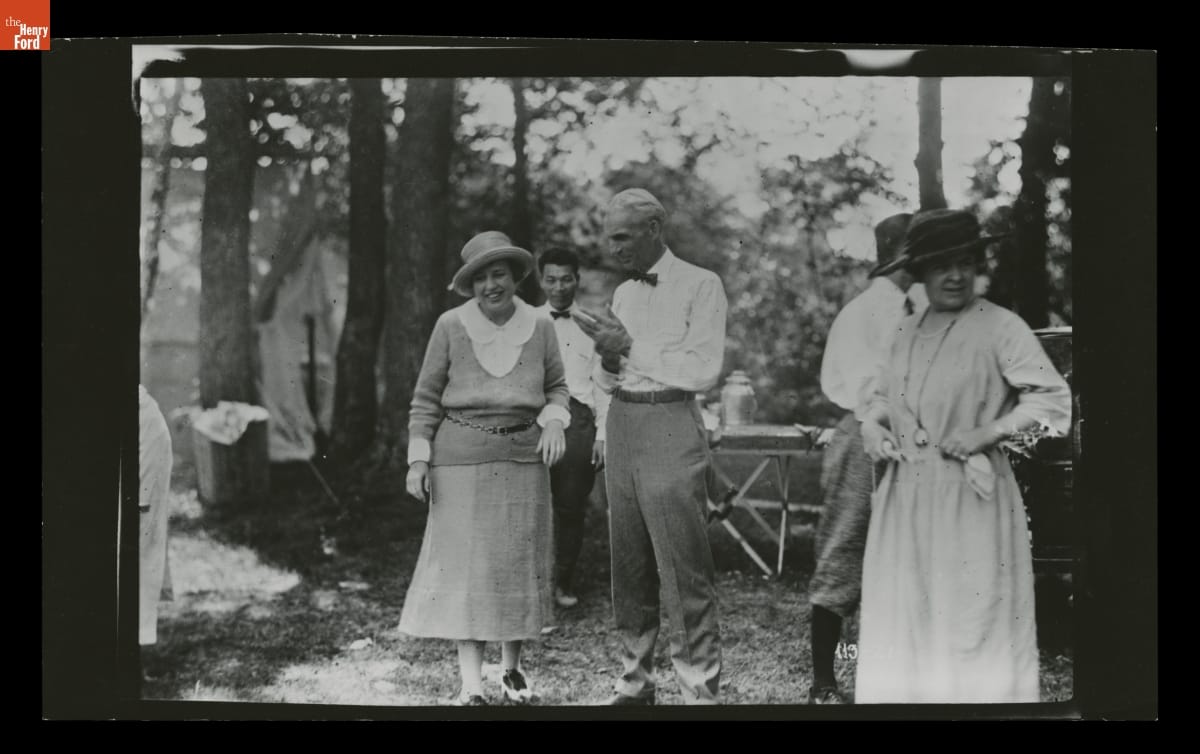

The Ford Family and Tsuneji Sato. Pictured left to right are Eleanor Ford, Sato, Henry Ford, Edsel Ford and Clara Ford on a 1921 camping trip in Maryland. / THF127405

A furor of anti-Asian discrimination and violence, especially on the West Coast where Asian American communities were expanding, eventually led to an informal agreement between President Theodore Roosevelt and Japan, known as the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907-1908, which restricted immigration from Japan until the Immigration Act of 1924 ultimately banned immigration from Asian regions altogether. Despite increasing xenophobia and restrictions, Tsuneji’s brother Junjiro (1870-1957) left their hometown of Wakuya, located in Japan’s northern prefecture, Miyagi, and made his way to the United States in 1894. At some point in the next 20 years, his younger brother Tsuneji would join him.

Tsuneji and Junjiro Sato. Date unknown. Source: Courtesy of the Sato brothers' descendants.

Upon the completion of Henry and Clara Ford’s sprawling Fair Lane Estate in 1915, Clara Ford contacted the Japanese Reliable Employment Agency of New York City looking for help. The Fords' former Japanese domestic servants, a couple who had worked for them at previous homes, wanted more for their lives in America: their own house and the ability to chase their own dream. Henry Ford obliged and gave the husband a job at his Highland Park plant, leaving Clara to inquire for someone who was single and “not as attached.” What the Fords received in Tsuneji Sato, now with the adopted English name of Thomas, was someone highly regarded who had the charisma and work ethic that could keep up with the unusual demands of an automobile magnate’s family. Continue Reading

Liberty Island Snow Globe, circa 1995 / THF175423

Mass-produced plastic snow globes (also known as snowdomes) are resonant and enduring objects of American culture. They have been sold as souvenirs and collectibles since the 1950s, but their story is nearly 150 years old.

Water-filled glass snow globes were first introduced at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1878. By 1879, there were at least five companies producing and selling snow globes throughout Europe.

In the early 1920s, snow globes were introduced in the United States, where they became popular collectors’ items. An American, Joseph Garaja, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, revolutionized the snow globe industry with a new method of assembly, patented in 1929. Hollywood films launched the mass popularity of snow globes, beginning with "Kitty Foyle: The Natural History of a Woman" (1940) and "Citizen Kane" (1941).