The Politics of a Press

During the 1920s, Henry Ford’s rampant collecting of Americana, which would become the basis of his museum’s collection, led him (through his purchasing associates and collectors) to pursue artifacts with compelling provenances attached to some of America's most fabled figures. While Ford maintained an interest in items of the “everyday” American, his avid pursuit of artifacts related to traditional American folk heroes, like George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, aligned with the interests of other collectors of the time. It should be no surprise, then, that when Ford learned about a printing press purportedly used by celebrated writer and humorist Samuel Clemens, otherwise known as Mark Twain, he leveraged his national network to acquire it.

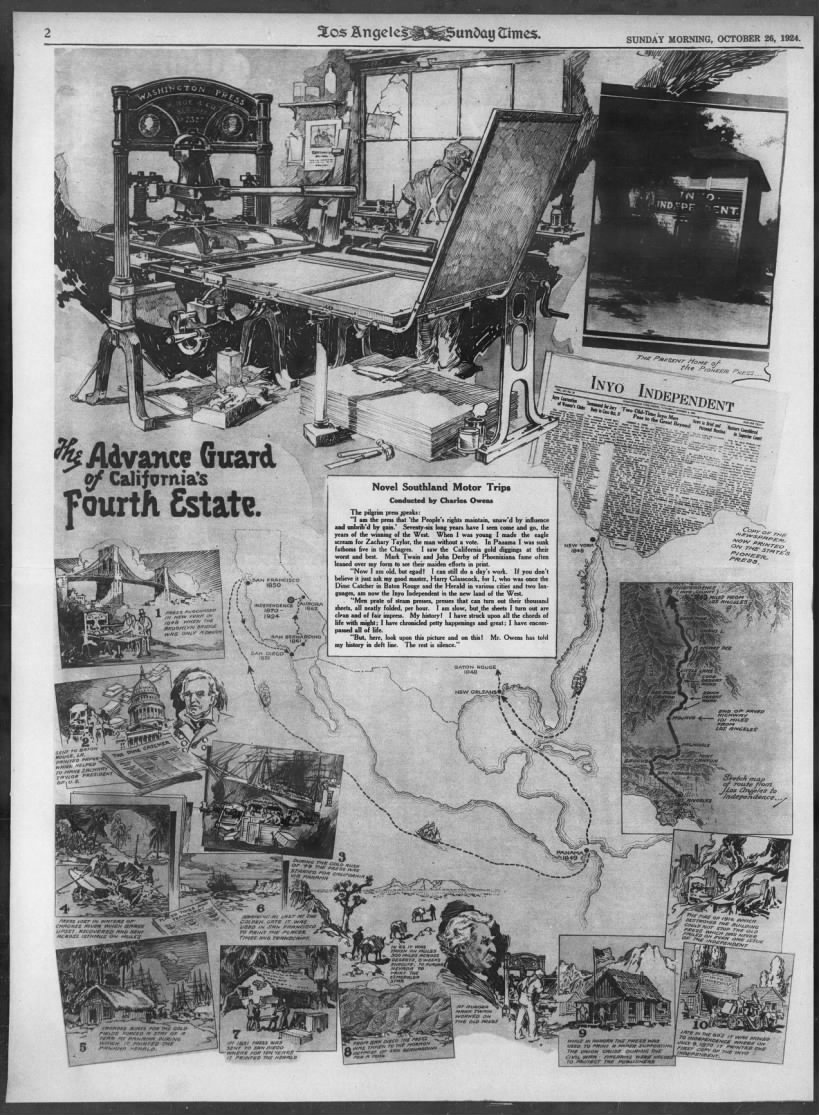

Washington press, circa 1848, decorated with reliefs of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. / THF101402

The printing press, manufactured in 1848 by R. Hoe & Co. of New York City, was a hardy survivor. By the time Henry Ford became aware of its storied history in the mid-1920s, it had made its way from its birthplace on the East Coast of the United States to the southeastern Sierra Nevada mountains via a continental crossing over the Isthmus of Panama. Its journey included falling off a transport boat into the Chagres River, being moved by mules through the Central American jungle, surviving a sinking boat in the Gulf of Tehuantepec, and enduring one of the many fires that terrorized early San Franciso — a city the press was never originally destined for. This Washington press came with a lighter frame than other presses of the time and could also be easily disassembled for moving and was more powerful, simpler and cheaper than other presses on the market. R. Hoe & Co. went on to manufacture over 6,000 of these presses between 1835 and 1902.

This modern photo shows the press with its tympan raised. / THF117871

The popularity and affordability of the Washington press made it accessible to editors and printers like John Judson Ames, who, in 1848, allegedly had this press shipped from New York to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Once set up, Ames used the press to print a political campaign paper called the Dime Catcher in support of the Whig Party’s nominee for president, Zachary Taylor — a national war hero uninterested in politics who would die early in a term characterized by political turmoil involving western expansion and slavery. Ironically, the first paper printed by the press celebrated the life of a man whose actions during the Mexican-American war and whose inactions regarding the institution of slavery afterward largely shaped the life the press would have.

Zachary Taylor campaign buttons, 1848. / THF157406

Before finding a home in the Owens Valley of southeastern California for over five decades, the press had passed through the valley once before on its way from San Bernardino to the mining boomtown of Aurora in Nevada — a journey that required a military escort at some point and the press being hauled by a team of oxen through mountain passes and the Mojave Desert. It’s in Aurora where the press picked up its supposed Mark Twain association.

A pictorial from the rotogravure section of the Los Angeles Times, dated October 26, 1924, detailing the legendary history of the press. It’s possible Henry Ford first learned of the press through this illustration. / Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times digital archive.

The principal town of the Esmeralda mining district, Aurora welcomed hundreds of new residents in the spring of 1862, one being future author Samuel Clemens, who, after losing his job during the Civil War as a Mississippi riverboat pilot, followed his brother west seeking to strike it rich in newly discovered gold and silver mines. While in Aurora, Clemens decided to follow his passion for writing and began reporting on his experiences for the Territorial Enterprise, a newspaper located in the larger mining town of Virginia City. After leaving for Virginia City at the end of 1862, Clemens adopted the name Mark Twain and became a popular newspaper reporter in Nevada and California.

Shown on display in The Henry Ford’s “Fully Furnished” exhibit, this table belonged to Mark Twain (1835-1910), American author and humorist whose real name was Samuel L. Clemens. His daughter Clara gave the table to Henry Ford, along with a portrait of her father, in the 1930s. / THF55050

Another new resident in Aurora that spring was Mexican-American War veteran and owner of the press Edwin A. Sherman. An ardent Unionist, Sherman not only wanted to take advantage of new markets for newspapers but also to protect and promote Union principles in the often Confederate-influenced settlements of the ever-expanding regions of western America. Using the press, Sherman established the newspaper known initially as the Esmeralda Star, where the publishing of his pro-Union views created a difficult time for him in Aurora as secessionist supporters made various threats and assassination attempts. Sherman, who provided these details in a thorough recollection of his life, made no acknowledgment in the recollection of ever crossing paths with Clemens.

“Gold Washing in the California Mines,” 1865-1870. (THF108431). In 1848, the United States obtained present-day California from Mexico. Later that year, gold would be found in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, bringing thousands of settlers to the region. By 1849, fierce debates were taking place in Congress around granting statehood to California as a free, non-slavery state.

For the press and Sherman, Confederate threats were nothing new. In 1861, Sherman had left San Bernardino, a former Mormon outpost turned mining town in the San Bernardino Valley of southern California, due to the same reasons. Earlier in the year, Sherman had purchased the press and began a newspaper called the San Bernardino Patriot, through which he outspokenly supported Abraham Lincoln and the Union. Even though it was the only paper published in the county, circulation was low because many citizens of San Bernardino strongly supported the Confederate cause. In the summer of 1861, Sherman alerted the Union Army in California to pro-Confederate plans to blow up his newspaper’s office and spur general lawlessness, a claim that resulted in the stationing of Union troops in the area and ultimately provided motivation for Sherman to leave the area.

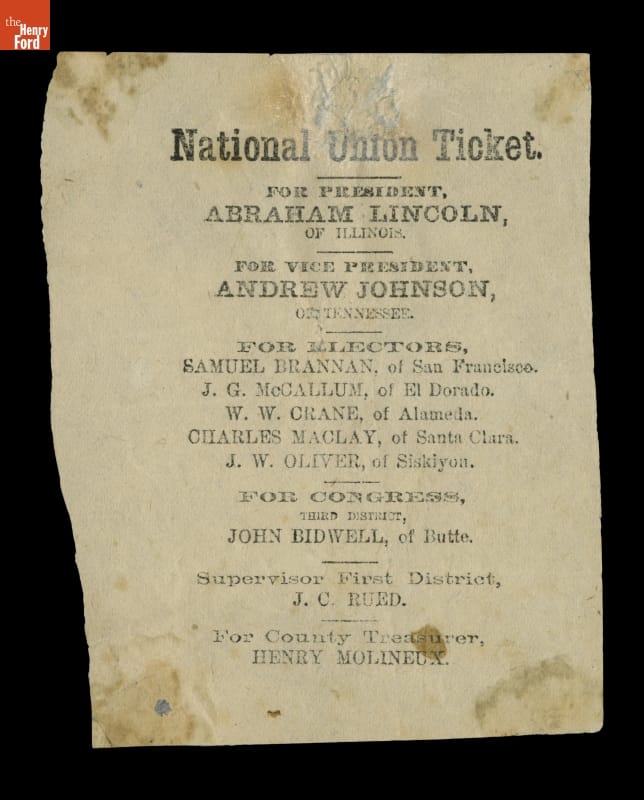

During the mid-1800s, Americans used preprinted ballots to vote. Political parties printed and distributed ballots, like this one from California’s 3rd Congressional District, sometimes through local partisan newspapers. / THF127815

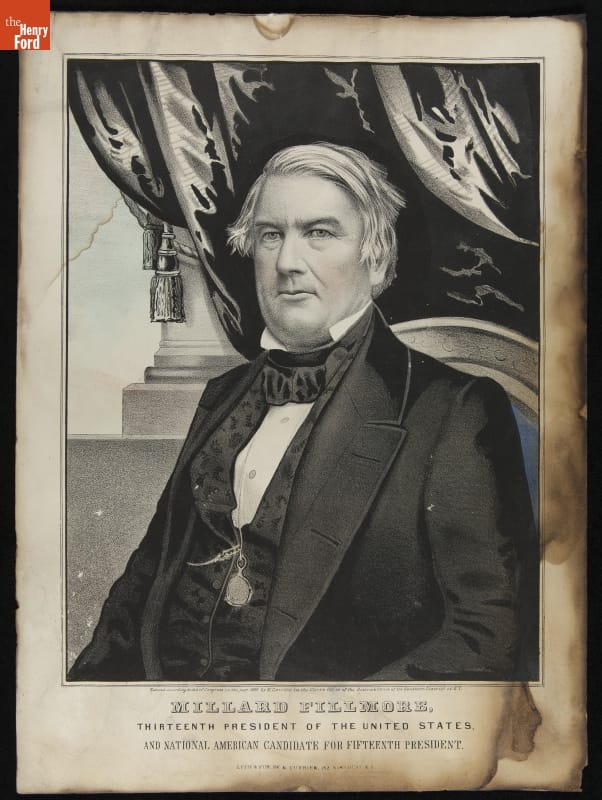

Prior to its use by Sherman, the press had been the political tool of John Judson Ames in Louisiana before he hauled the press to California via Panama. Ames had brought the press to San Bernardino from the burgeoning coastal town of San Diego in 1860, during a mining boom, to print his nonpartisan San Bernardino Herald, but he had spent the previous nine years in San Diego as editor of the San Diego Herald, where he courted an array of political viewpoints. With the editorial motto “Independent in all things, neutral in nothing,” Ames used the San Diego Herald (and the printing press) to support anyone, from Democrat John Bigler for California governor (which Bigler served as from 1852-1856) to suggesting Texas “hero” Sam Houston run for president. Ames also notably endorsed Millard Fillmore of the nativist Know Nothing Party in the mid-1850s as well as one of California’s first senators, William McKendree Gwin, a Mississippi slaveholder whose loyalty lay with the slaveholding South and whose interest in California focused solely on territorial expansion that benefited the Southern economy.

Vice president to Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore took over as president after Taylor’s death in 1850. Failing to win reelection in 1852, Fillmore ran again in 1856 (and lost) under the banner of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know Nothing Party, later known as the American Party. / THF256386

In the 1920s, the fate of the printing press lay embroiled in the political Water Wars of California, where the residents of Owens Valley remained in a hostile fight with the City of Los Angeles over the diversion of water from the Owens River by aqueduct. The conflict — stoked by then-owner of the press Harry Glasscock through his local newspaper — boiled over in 1924 with guns being drawn and threats to blow up the aqueduct followed through on. After an embezzlement scandal at the valley's major bank left residents, including Glasscock, with no personal savings, local resistance took a severe blow. The press became a liquidated asset in the mid-1920s, but by that point, its mythic story had already been publicized. The allure of Mark Twain resulted in the printing press being immediately pursued by the agents of Henry Ford and brought to Dearborn, where it now resides in The Henry Ford’s collections.

Ryan Jelso is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.