Indigenous People at Yellowstone: From Erasure to Inclusion

| Written by | Donna R. Braden |

|---|---|

| Published | 6/17/2022 |

Indigenous People at Yellowstone: From Erasure to Inclusion

| Written by | Donna R. Braden |

|---|---|

| Published | 6/17/2022 |

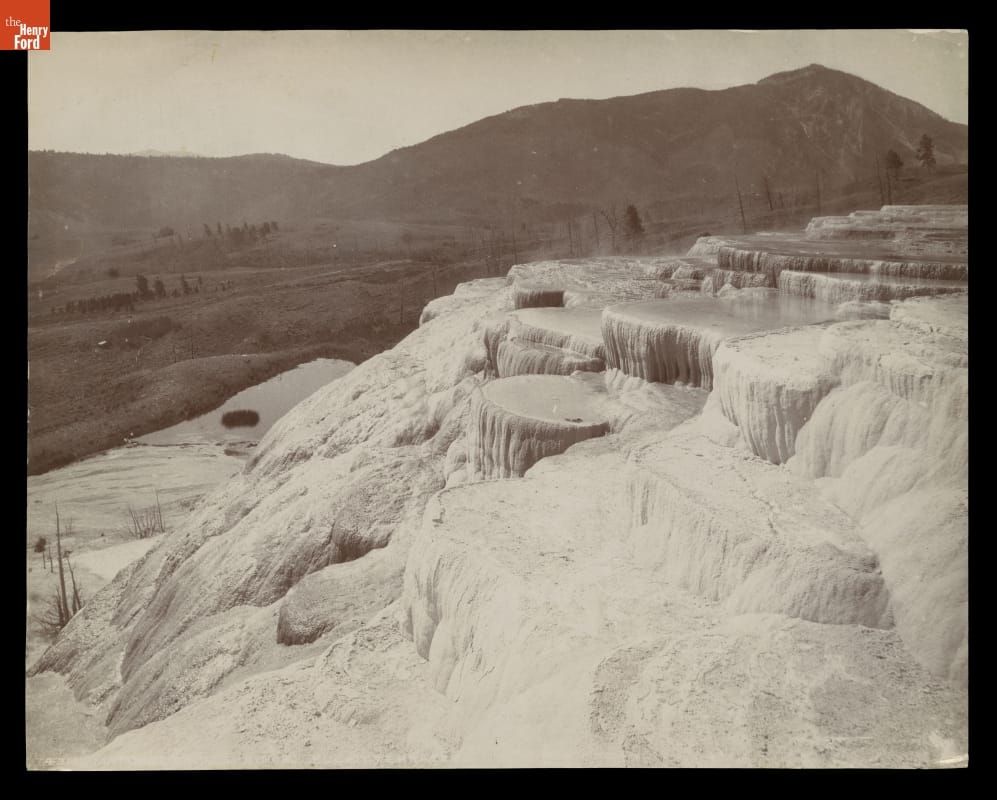

For decades, many Americans shared a common misperception that Indigenous people feared the geysers at Yellowstone. / THF120298

Until recently, much of the American public has shared a common misperception that few Indigenous people had ever ventured within the boundaries of what became Yellowstone National Park. Story had it that these people were afraid of the geysers, or that they felt that the hissing steam vents were signs of angry gods or evil spirits. In fact, the presence of Indigenous Americans was purposefully erased from the story of Yellowstone National Park, beginning with the first white “scientific” expedition there in 1871. This erasure, which lasted through most of the park’s history, is only recently beginning to change.

Some Indigenous people, in their pursuit of the large herds of bison to the east, created a trail that passed near what is now known as Mammoth Hot Springs. / THF120351

Archaeological evidence now indicates that as far back as 10,000 years ago, several bands of Indigenous people regularly passed through this area, primarily hunting bison, bighorn sheep, elk, and deer. In historic times, the area continued to serve as a crossroads for many Indigenous groups—including Crow, Shoshone, Bannock, Blackfoot, Nez Perce, and Flathead—who followed the Yellowstone River and other waterways through what eventually became the boundaries of the park. They tracked small buffalo herds, elk, and deer in the mountains and forests during the summer months and followed these animals to the warmer geothermal area of the Yellowstone Basin during the bitter winter months. Some of these groups crossed through the area to pursue the great herds of bison in the plains farther east, creating a trail that passed through the area now known as Mammoth Hot Springs and stretching eastward across what is known today as Lamar Valley. Early white hunters, trappers, and explorers not only followed the trails that Indigenous people created, but it is from these people that they first heard the fantastic stories of geothermal wonders in the Yellowstone Basin.

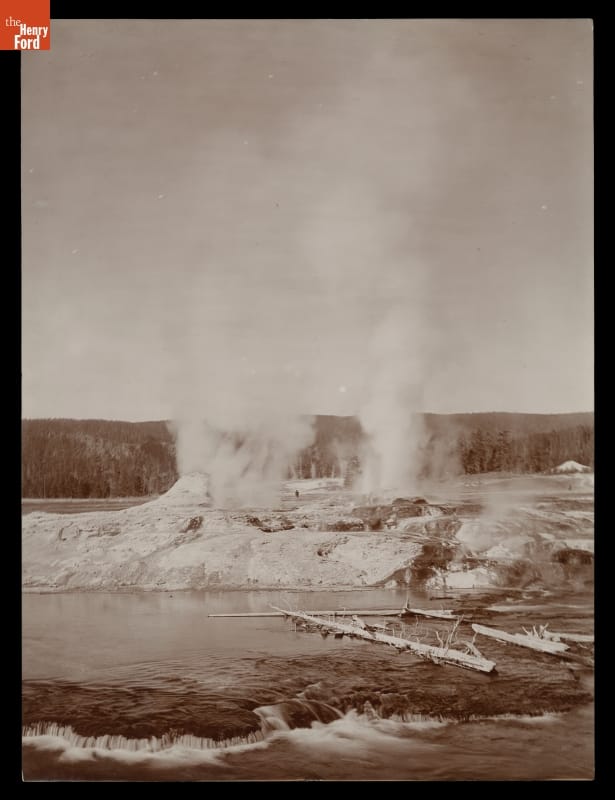

Many early photographs of the wonders of Yellowstone, like this “Grand Group” of geysers, were probably taken by William Henry Jackson, one of the people who accompanied Ferdinand Hayden on his 1871 expedition through what would become the park. / THF120369

The process of Indigenous erasure in Yellowstone began in earnest with the Hayden expedition of 1871—a large, government-funded expedition led by geologist Ferdinand Hayden to study, collect specimens in, and map out the confines of the Yellowstone “wonderland” that had been receiving so much recent attention. Hayden and members of his expedition were able to observe firsthand the places that had been described primarily in stories told by Shoshone and Bannock people—astonishing places like “The White Mountain” (which became known as Mammoth Hot Springs) and the spectacular geysers, bubbling mud pots, and hissing steam vents situated within the geothermal area of the Yellowstone Basin. As a result of this expedition, Hayden laid claim to this unique landscape on behalf of the United States government and the American people, choosing to ignore the longstanding use of the region by Indigenous people. Instead, the expedition report pointed to Yellowstone’s wonders as proof of the country’s “exceptionalism”—that is, Americans’ long-sought evidence that the United States was unique and exceptional when compared with other nations of the world.

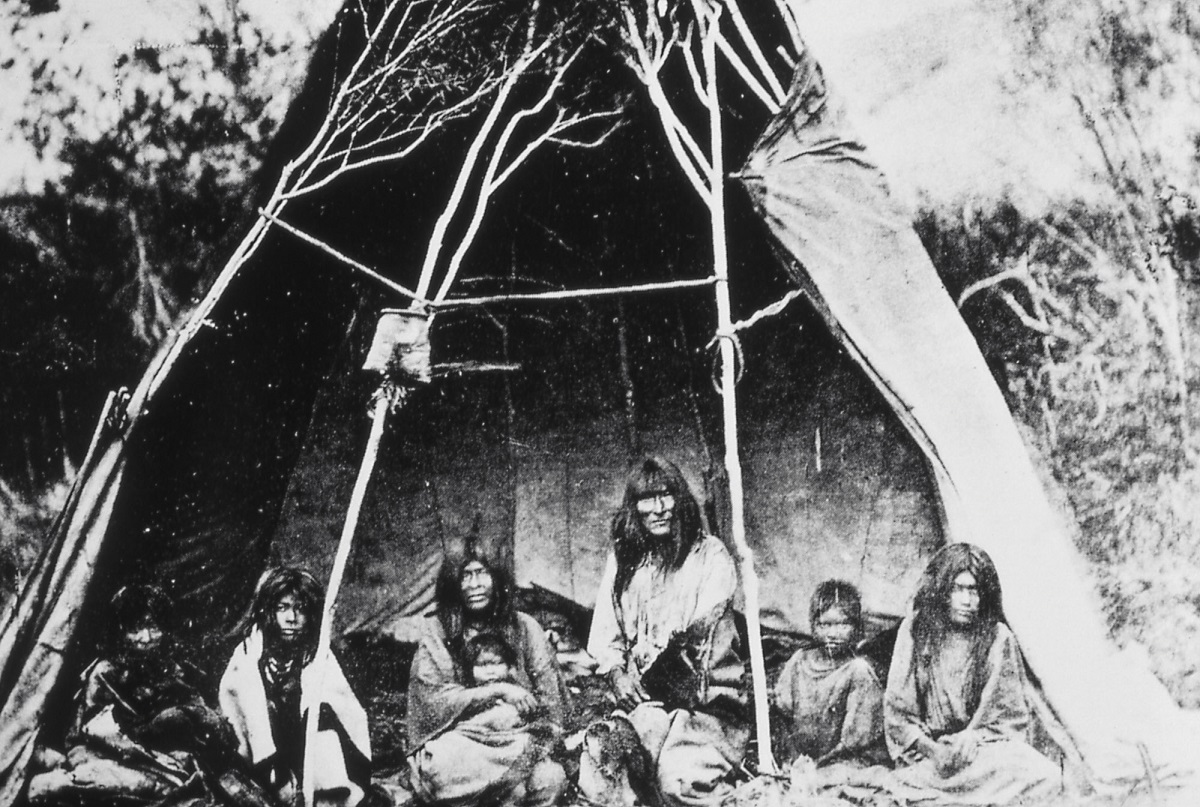

Photo of "Sheepeater" Shoshone, William Henry Jackson, 1871. / Public domain photo from National Park Service

By the time of the Hayden Expedition, the only Indigenous people still known to inhabit the area were a by-then considered poor and lowly band of Eastern Shoshone called Sheepeaters (Tukudeka or Tukadika). A wealth of recent archaeological information has pointed to the conclusion that this band had inhabited and roamed this area for thousands of years—not the mere 200 years that early white explorers surmised (a story that then became widely accepted). These people had developed a remarkably sustainable way of life, taking advantage of the once-large population of bighorn sheep for food, clothing, blankets, tools, and bows. Early white trappers observed this band’s self-confidence, intelligence, friendliness, and willingness to trade their fine-quality hide clothing, horn bows, and obsidian arrowheads. Unfortunately, the bighorn sheep population plummeted as the result of diseases brought by white settlers’ domestic sheep. White hunters and settlers also decimated other game and polluted the streams in which these people had fished. No wonder, then, that by the 1870s white explorers of the area described these people as starving and miserable.

In 1903, this monumental stone gateway was completed to mark the north entrance to Yellowstone National Park. The words “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,” inscribed above the arch, are taken directly from the legislation that created Yellowstone back in 1872. / THF120280

The widely publicized and highly celebrated Hayden report rapidly led to the creation of a bill to set the area aside as a national park, a “resort for all classes of people from all portions of the world,” a democratic landscape of tourism. When the question of Indigenous claims to the area under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie was raised, the argument was made that the land was simply too hostile for Indigenous people to live there. Though this was not true, Hayden’s expedition report had already justified the removal of Indigenous people from the area. The bill passed easily, with the help of aggressive lobbying by the Northern Pacific Railroad and the strong desire by members of Congress to use the bill as a way to help unify a Civil War-torn nation. The Yellowstone National Park Protection Act (or, simply, the Yellowstone Act) was placed on President Ulysses S. Grant’s desk on March 1, 1872. President Grant signed it without fanfare. During the 1870s, the Sheepeaters were easily rounded up and exiled to the Wind River (Wyoming) and Fort Hall (Idaho) reservations to live with other bands of Shoshone, along with Bannock and Arapaho people.

Early tourists typically boarded horse-drawn carriages to view the sites at Yellowstone National Park. / THF200464

When Yellowstone became a national park, no funds were allotted to administer or manage it. But an 1877 incident involving an encounter between another Indigenous group and two groups of tourists in the park changed that. The incident involved a group of Nez Perce (Nii mi’ipuu) crossing through the park in an epic flight to avoid the U.S. Army, who was pursuing them to force their removal from their ancestral homeland in eastern Oregon to a tiny reservation in Washington. This incident, which unfortunately involved violence and hostage-taking, created a national media sensation. Many personal accounts of the episode emerged afterward, with some indication that those who were involved sympathized with the plight of the Nez Perce. The Nez Perce group managed to successfully evade the army until the soldiers finally caught up with them 40 miles south of the Canadian border—in an attempt to join Sitting Bull’s Lakota band.

As a result of the widespread publicity and furor raised by this incident, Congress finally committed some money to managing the park. As tourism increased, Congress pressured Yellowstone park administrators to control the “savages” because it was assumed that they would endanger the park’s visitors. After that time, park administrators aggressively downplayed any presence of Indigenous people, not wanting the park’s well-heeled guests to risk crossing paths with them, or to even be worried that they might. By 1882, all Indigenous groups had been banned from the park.

Sheepeater Cliff was named after the only Indigenous people that lived on in public memory as having inhabited the Yellowstone area. / Photo by NPS/Jim Peaco

Once the real presence of Indigenous people had been erased from the landscape, park superintendents, railroad publicists, and tourists alike could look back—safely, nostalgically, and romantically—on the one-time presence of Indigenous people there. For example, when park administrators came across the remnants of wickiups (temporary shelters made from poles leaned and tied together, covered with brush or grass) eight miles south of Mammoth Hot Springs, they assumed these were made and used by the Sheepeaters. Since this was the only group still in the public memory as having inhabited Yellowstone, they felt that they were honoring their one-time presence by naming the natural feature near there “Sheepeater Cliff”—though this band did not live in that area and likely did not build these shelters. Once established, the perception that no Indigenous people had ever set foot inside the current boundaries of Yellowstone National Park (except for the Sheepeaters) persisted for decades.

In recent years, however, archaeologists, historians, and Indigenous activists have begun to correct the narrative of Indigenous presence and habitation on this land. In addition, administrators at Yellowstone National Park have also been making a concerted effort to elevate Indigenous voices and incorporate Indigenous knowledge systems into their research and programs (see, for example: https://roadtrippers.com/magazine/yellowstone-150-native-american-voices/ and https://www.nps.gov/yell/getinvolved/150-years-of-yellowstone.htm). Today, they recognize at least 27 distinct American tribes that have historic and present-day connections to the land and resources of the park. As champions of ecological connectivity, Indigenous people have been galvanizing action to protect Yellowstone’s wildlife, helping to relocate bison culled from the park, raising awareness on living with bears and wolves in the wider landscape, and enlightening administrators and the public on other aspects of environmental conservation related to the Yellowstone ecosystem. For the 150th anniversary of the park in 2022, administrators have been “shining a light” on Indigenous people whose past, present, and future are an essential part of Yellowstone’s story. As Cam Sholly, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, proclaims, “This isn’t just about the last century and a half. We also want to use this anniversary to do a better job of fully recognizing many American Indian nations that lived in this area for thousands of years prior to Yellowstone becoming a park…. The engagement we’re doing now will help set a stronger foundation for collaboration well into the future.”

As erasure shifts toward inclusion—through published materials, behind-the-scenes collaboration, and public programming—the historic and present-day connections of Indigenous people to Yellowstone National Park will continue to play an important role in the park’s future.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. For recent books aimed at greater inclusion of Indigenous people in Yellowstone’s history, she recommends Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America by Megan Kate Nelson (2022) and Wonderlandscape: Yellowstone National Park and the Evolution of an American Cultural Icon by John Clayton (2017).

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Series | |

Themes |