Remembering Lincoln

| Written by | Donna R. Braden |

|---|---|

| Published | 2/12/2018 |

Remembering Lincoln

| Written by | Donna R. Braden |

|---|---|

| Published | 2/12/2018 |

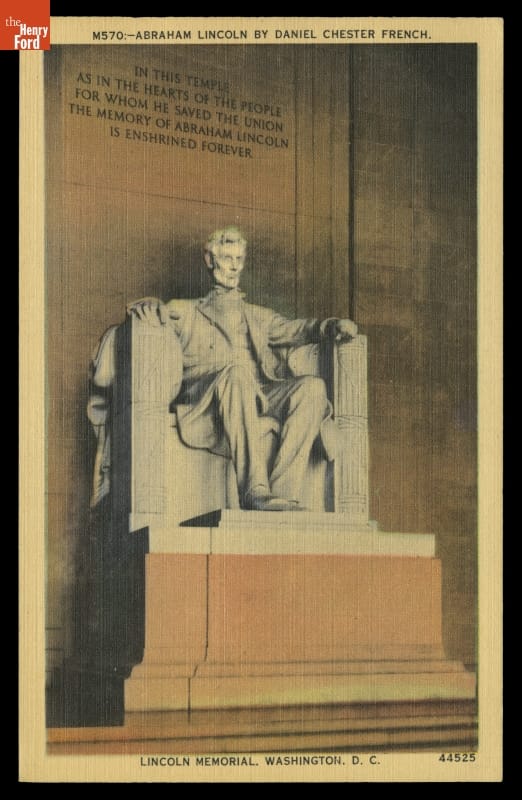

This statue was designed to reveal Lincoln’s “essential nobility” while the inscription above him was intended to reinforce national unity. THF121596

By the first decade of the 20th century, memories of the real Abraham Lincoln had faded. A new generation of Americans came of age who had only heard the stories, the myths, and the legends. It was this generation who transformed Lincoln the real man into Lincoln the hero.

During the early decades of the 20th century, America was becoming a complex place--an urban-industrial nation, a serious player on the world stage, and a place with an increasingly diversified population of foreign-born residents. Struggling to come to terms with the change and uncertainty of the era, people looked to Abraham Lincoln--the humble, imperfect, self-educated “common man”--for comfort and reassurance. Abraham Lincoln, better than any single individual, seemed to embody the democratic principles upon which the country had been founded. It was during this era that Abraham Lincoln replaced George Washington as America’s most venerated president.

Just about everyone could find something meaningful by invoking his image, his name, or his character.

The Lincoln Centennial

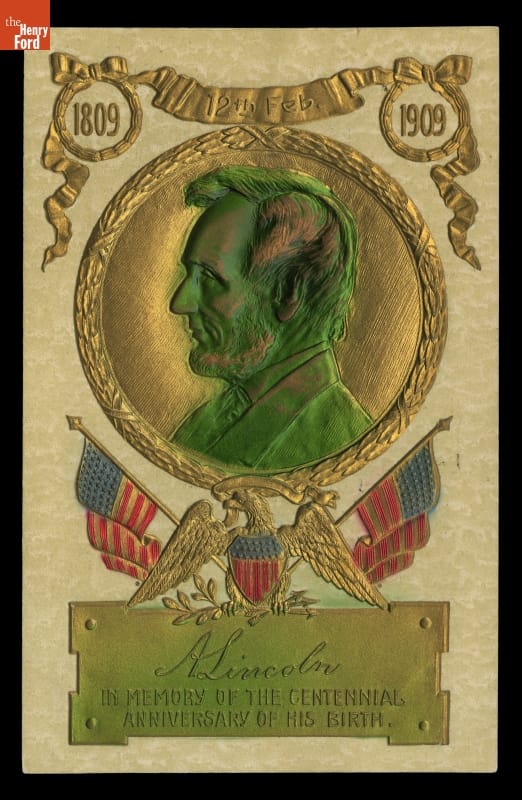

Postcards abounded as popular keepsakes of the Lincoln Centennial, including this German-imported embossed example. THF121598

On February 12, 1909, virtually the entire nation honored Abraham Lincoln on the 100th anniversary of his birth. In city after city, Americans put aside their regional differences and sought national unity by venerating Lincoln as a “man of the people.”

The national celebration was a grassroots effort--mainly the work of local governments, civic organizations, and print media. Even in the old Confederate states, Lincoln’s character was held up as a model of humility and generosity.

Sadly, Jim Crow laws in the South and practices in the North prevented African Americans from taking part in most of these observances. In their own communities, they honored the memory of Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator.”

The Lincoln Highway

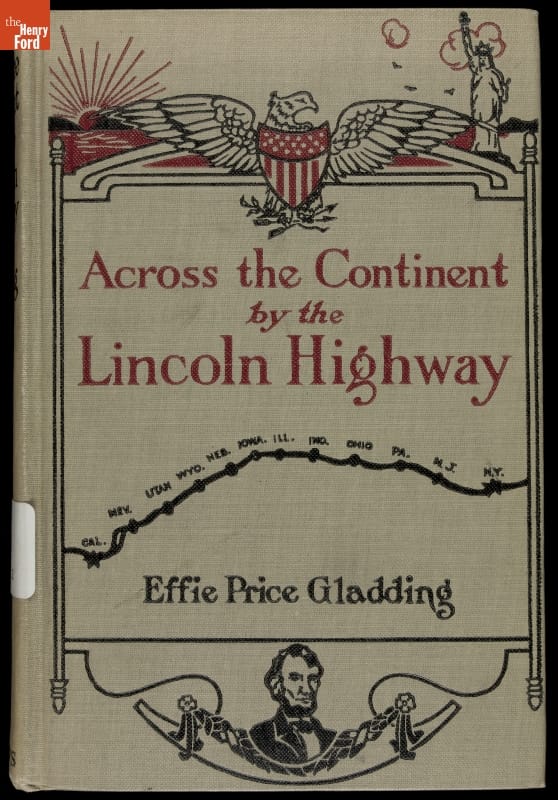

Abraham Lincoln and symbols of national unity are pictured on the front of this 1915 travelogue. THF204498

In 1912, the few “good” roads that existed for automobile travel were dirt-covered--making them bumpy and dusty in dry weather and virtually impassable when it rained. To get anywhere, it was better to take a train than to drive.

Enter Carl Fisher, an automobile headlight entrepreneur who had the ambitious idea of creating a highway that would cross the continent from New York City to San Francisco. He turned to manufacturers of automobiles and automobile accessories for support and financial backing. His biggest advocate became Henry Joy, president of the Packard Motor Car Company.

It was Joy’s idea to name the road in honor of Abraham Lincoln. Joy was only a year old when Lincoln was assassinated but his father had filled him with stories of the martyred president. He felt that connecting the road with Lincoln would both increase both its patriotic appeal and enhance its symbolism as the road that unified the nation--a fitting parallel to Lincoln’s great achievement of preserving the union.

Abraham Lincoln and World War I

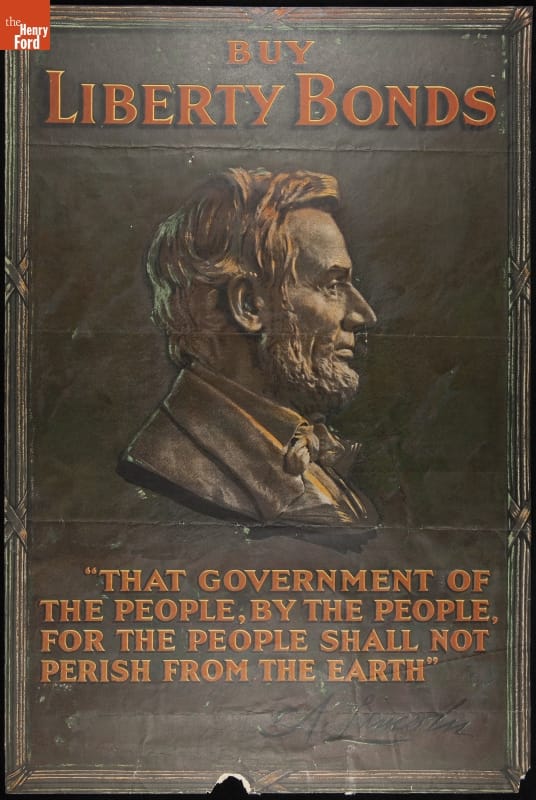

This World War I poster includes an excerpt of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. THF239921

During the First World War, Lincoln’s reputation extended beyond American shores to the international arena. For, who could more perfectly symbolize the international fight for freedom--the fight to make the world safe for democracy--than America’s own Abraham Lincoln? Although Lincoln’s tactics as Commander-in-Chief during the Civil War had been questioned during his own time, his policies, decisions, defense of war, and crackdown on obstructionists now seemed to exemplify visionary leadership.

Reviving Lincoln as a symbol of wisdom, courage, and sacrifice during World War I might have been propaganda but it worked its magic on the American public. Northerners and Southerners enlisted in droves and fought alongside each other in battle. African Americans’ loyalty to Lincoln inspired thousands to enlist and bravely serve their country--though largely in segregated units.

Lincoln Logs

This Lincoln Logs set dates from about 1960—the era of TV Westerns and the Davey Crockett craze. THF6627

Beloved by generations of young children, Lincoln Logs have been around since the 1920s. Oddly, their origin had nothing to do with Abraham Lincoln or log cabins. John Lloyd Wright, Lincoln Logs inventor and son of the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, claimed that the idea for this sturdy, interlocking “log” playset came to him in Tokyo, Japan in 1916, while visiting the construction site of the hotel designed by his father. The Imperial Hotel, as it was named, was built upon a unique, earthquake-proof foundation of interlocking beams.

By the time Wright patented his invention in 1920, he was calling it a “Toy-Cabin” construction set. In 1924, it came on the market as “Lincoln Logs: America’s National Toy.” Further cementing the connection, a 1928 advertisement claimed that Lincoln Logs provided, “All the romance of the early days of Abraham Lincoln with all the thrill of Pioneer Life.” Lincoln Logs were an instant success--leading to larger and more elaborate play sets that included cowboys, pioneer towns, forts, horses, and livestock.

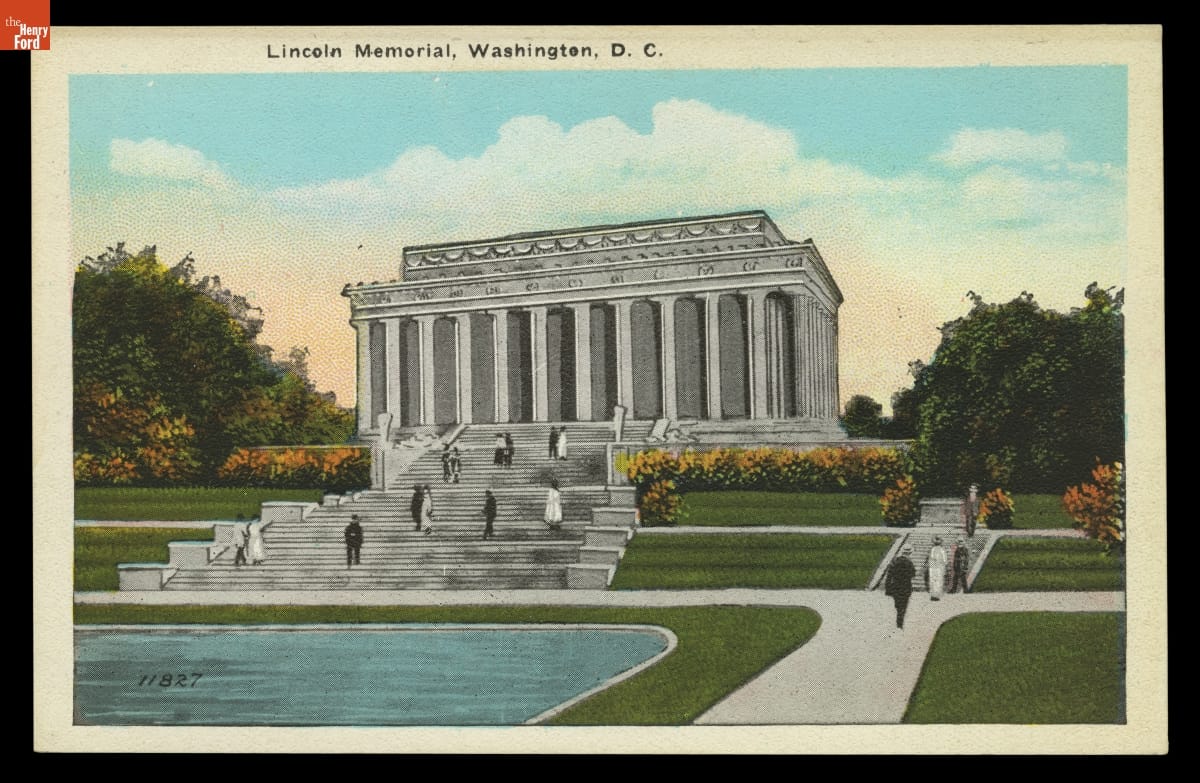

The Lincoln Memorial The Greek temple-like design of the Lincoln Memorial symbolizes the democratic principles for which Lincoln stood. THF121594

The Greek temple-like design of the Lincoln Memorial symbolizes the democratic principles for which Lincoln stood. THF121594

During the 1909 Lincoln Centennial, Congress found itself in the embarrassing position of having no plans to honor Lincoln in the nation’s capital. So in 1911, a Lincoln Memorial Commission was created. The commissioners saw this Memorial as both a tribute to Lincoln and an important symbol of a reunified nation. They chose to avoid any literal references to Lincoln’s accomplishments as President as well as his role as the “Great Emancipator.” They felt that might offend people, especially Southerners. No, this expression of Lincoln must transcend all that to represent the man who defended democracy and saved the Union. It must idealize Lincoln’s memory and reveal his “essential nobility.”

After delays in the completion of the enormous statue, the Lincoln Memorial was finally dedicated in 1922. In keeping with federal policies on segregation, African American guests to the dedication were seated in a “colored section” off to the side, where they reported rude treatment by military attendants.

Henry Ford and Abraham Lincoln In this 1934 photograph, Henry Ford poses in front of the Logan County Courthouse with Lincoln portrayer Charles Roscoe Miles. THF121394

In this 1934 photograph, Henry Ford poses in front of the Logan County Courthouse with Lincoln portrayer Charles Roscoe Miles. THF121394

In his great admiration for Abraham Lincoln, Henry Ford was like many other Americans of his generation. Born two years before Lincoln was assassinated, he had grown up surrounded by Lincoln myths and stories. His Uncle Barney’s regiment--the Union Army’s famed 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry--had even escorted President Lincoln’s casket from the Old State House in downtown Springfield, Illinois, to its final resting place in Oak Ridge Cemetery about two miles away.

As Henry grew from a youth to an enterprising automobile entrepreneur, Lincoln’s lessons were not lost on him. According to the stories, Lincoln’s success had been due to such character traits as honesty, temperance, industry, and pluck. Furthermore, Lincoln embodied the ideals of the “self-made man,” rising up from humble beginnings to make something of himself.

By the 1920s, a now-wealthy Henry Ford began to amass a collection to honor his hero--including the rocker that Lincoln had been sitting in at Ford’s Theatre the night he was assassinated. When an antique dealer friend told him of a neglected courthouse in Lincoln, Illinois, in which Lincoln had practiced law, Henry Ford knew that this was the key he had been searching for. It would become the centerpiece of an “exhibit” in his Early American Village (now Greenfield Village) depicting the move from slavery to emancipation. The building would also house his Lincoln collection, to serve as a teaching tool for “the application of the practical principles of justice and common sense so often exemplified by Abraham Lincoln in real life.” Ford’s workmen dismantled and reconstructed the courthouse in Greenfield Village in record time for its grand opening on October 21, 1929.

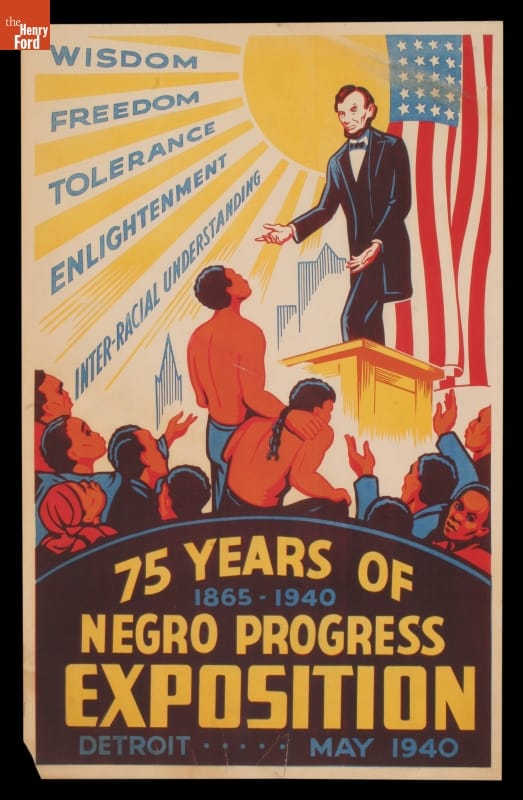

75 Years of Negro Progress Exposition Lincoln’s image looms large in this poster advertising the nine-day Negro Progress Exposition. THF61510

Lincoln’s image looms large in this poster advertising the nine-day Negro Progress Exposition. THF61510

Abraham Lincoln remained a powerful source of inspiration to African Americans through the early 20th century, as they struggled to realize the promise of emancipation. The image of Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator” belonged particularly to them. Those who had experienced firsthand Lincoln’s gift of freedom from slavery considered him their savior and they passed down to younger generations the intensely personal love and reverence they felt for him.

Seventy-five years after Lincoln was assassinated, Detroit was host to a nine-day exposition celebrating both past achievements and “new horizons of advancement.” Each day of the Exposition offered a theme, including Business Day, Women’s Day, Race Relations Day, Youth and Athletic Day, and Patriotic Day. Joe Louis, World’s Heavyweight Champion, made an appearance and Dr. George Washington Carver’s laboratory was featured.

In reality, progress for African Americans had been and would continue to be slow. Most of the earlier dreams of freedom and racial equality had failed. Jim Crow laws and practices were very much in effect. Discrimination was widespread, in the North as well as the South. Race riots continued. It would be 15 more years before Rosa Parks would refuse to give up her seat on a bus, sparking the Civil Rights movement. Later Civil Rights leaders would, in fact, downplay Lincoln’s role in their plight--feeling that reinforcing his image as the “Great Emancipator” diminished their own struggles and African Americans’ own contributions.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Themes |