Posts Tagged 20th century

Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle: Enduring Kitchen Icons from Corning

Three brands developed by Corning Glass Works during the 20th century — Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle — became household names that revolutionized American kitchens and endured decades of changing consumer tastes and expectations.

Corning Glass Works found both industrial and household applications for Pyrex. The company produced Pyrex insulators and laboratory glassware alongside its increasingly popular ovenware in the 1930s. Pyrex Perfect Antenna Insulator, 1930-1939. / THF174626

In 1908, scientists at Corning developed glass that could withstand extreme temperatures. It was initially used for industrial products like railroad lanterns and battery jars. Hoping to broaden the market, Corning spent years testing possible household applications. Encouraged partly by the success of one notable experiment — when Bessie Littleton, whose husband was a Corning researcher, used a modified glass battery jar to bake a cake — Corning introduced Pyrex, a line of temperature-resistant glass cookware. The launch of Pyrex in 1915 inaugurated a new Corning division dedicated to consumer products.

This early advertisement for Pyrex ovenware touts its many advantages. National Geographic, 1916. / THF709296

Pyrex bakeware entered the market at an advantageous time. In the early 20th century, the principles of scientific management — used in industrial settings to improve efficiency — found their way into the kitchen. Transparent Pyrex ovenware fit the bill — it performed well, was easy to clean and could go from oven to table. The Pyrex line was expensive at first — marketed initially to women of means interested in up-to-date products.

Pyrex Flameware Percolator, 1939-1951. / THF191912

Pyrex’s excellent performance in baking was unquestionable. Yet, to become a greater contender in the cookware industry, Pyrex would need to be usable for top-of-stove cooking on an open flame. The introduction of Pyrex Flameware in 1936 added this feature, increasing the product’s appeal. Too, changes in manufacturing helped make Pyrex more affordable by the 1930s.

Corning Ware Casserole Dish, 1960-1961. / THF192899

Next up? The accidental discovery of a new material — glass-ceramic — by a Corning research chemist in 1952. The gleaming white opaque material could withstand extreme cold and heat and didn’t break when dropped. First used in nose cones for radar-guided missiles, this new material found its way into the kitchen in 1958 as Corning Ware — a line of innovative, shatterproof cookware that could go right from the freezer to the oven or range and then to the table as a serving dish.

Corning advertisement, 1968. / THF710401

Versatile, durable, attractive and affordable, Pyrex and Corning Ware became staples in American kitchens.

Color and More

Pyrex Primary Colors Mixing Bowl Set, 1949-1957 and three Pyrex Primary Colors Refrigerator Dishes with Lids, 1947-1960. / THF167736, THF176489, THF176490 and THF176488

By the late 1940s, Corning sought to appeal to evolving post-World War II tastes with a focus on the center of the American home — the kitchen. Continuing the trend toward enlivening kitchens with new products in vibrant choices, Corning transformed Pyrex from colorless to colorful with the “Primary Colors” line, introduced in 1947. Customers could mix and match sets of cookware that were practical and functional but also stylish.

Cornflower Pattern Percolator, Teapot and Platter 1960-1961. / THF370218, THF370237, THF191905

Corning applied a similar styling approach to its revolutionary Corning Ware line. The popular Cornflower Blue pattern, introduced in 1958, became synonymous with Corning’s brand identity. It appeared on all sorts of products — most famously on casseroles but also on percolators, teapots and platters. Consumers could buy pieces as needed and eventually collect a color-coordinated set of cooking and serving ware. Later patterns reflected new trends and helped broaden the market for Corning Ware.

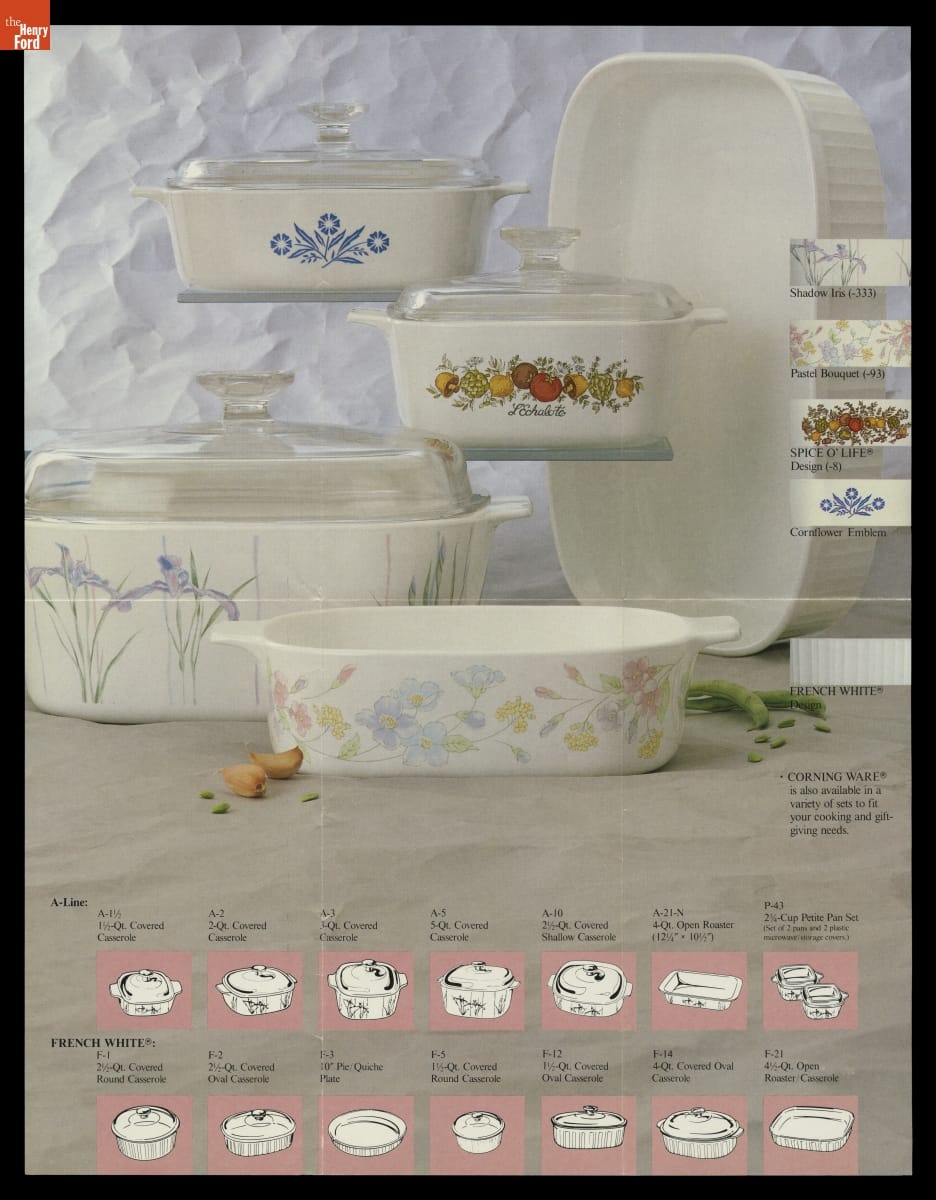

This Corning Ware brochure shows patterns available in 1987 — Shadow Iris, Pastel Bouquet, Spice O’ Life and the iconic Cornflower Emblem — as well as the now-classic French White line of casseroles. / THF709300

Revolutionizing the Dinner Table

Corelle Livingware cups and saucers in Butterfly Gold, 1971. / THF195008, THF195009, THF195011

Unlike Pyrex and Corning Ware — products made of new materials created without a singular purpose in mind — Corning deliberately pursued another kitchen innovation in the 1960s. The company thoroughly researched consumer preferences in dinnerware and then set to work on improving it. A breakthrough came in 1965 when a Corning scientist developed a laminating technique that produced very thin, yet very strong glass. Corning introduced Corelle Livingware, dinnerware made from this light and durable layered glass, in 1970.

Corelle Livingware dinnerware set in Spring Blossom Green, 1971. / THF195020

Corelle was a radical departure from the past, where expensive dinner sets consisted of many pieces, including luncheon plates and soup and salad bowls. By contrast, the first Corelle Livingware service consisted of a set of four large plates, four medium bowls, and four cups and saucers, retailing for the attractive price of $19.95. In addition, Corning provided a two-year guarantee to replace any piece that broke.

Corning’s savvy marketers compared Corelle to fine china. Product packaging with the slogan “looks, feels, and rings like china” depicted a mother “pinging” a Corelle plate. The company also offered consumers a selection of fashionable patterns. Pieces from the debut collection featured Butterfly Gold, Spring Blossom Green, Old Towne Blue and Snowflake Blue designs around the rim. Corning’s greens and golds were variations of the Harvest Gold and Avocado Green color schemes iconic of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Corelle was incredibly successful and changed middle-class American dining habits — it was chic yet durable and inexpensive enough for casual use. Corelle frequently sold out and was back-ordered throughout the 1970s. Corning continually added new “lifestyle” patterns and discontinued old ones to keep up with the latest decorative trends.

Still the Standard

Corning Pyrex FreshLock Plus food storage set with Microban antimicrobial product protection, 2022. / THF195359

Corning continually updated its Pyrex, Corning Ware and Corelle lines with new products that retained the qualities that had made them household names. The company sold its housewares division in 1998, but all three brands remained staples of American kitchens. In the 21st century, updated variations and marketing approaches appealed to changing tastes and lifestyle trends. Sets of Pyrex dishes designed for cold storage, portability and easy reheating featured locking plastic lids with odor-preventing technology. Marketers imagined new uses for classic Corning Ware, even designating some iconic French White casseroles as official companion pieces for the cult favorite Instant Pot brand of multicookers. (The company that manufactured Corning housewares merged with Instant Brands in 2019.) Continually updated Corelle patterns appealed to contemporary tastes.

Corelle Livingware dinnerware set in Northern Pines, 2022. / THF195362

Durable, convenient and stylish, the iconic brands developed by Corning in the 20th century continue to have relevance in today’s kitchens.

Charles Sable is curator of decorative arts, Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life and Saige Jedele is associate curator at The Henry Ford.

glass, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Charles Sable, 20th century

1938 Massey-Harris Model 20 Self-Propelled Combine in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF110572

Combines loom large on the floor of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, but they loom even larger on the physical and historical landscape of America’s agricultural heartland. Standing high on the horizon, combines both symbolize and represent the reality of the mechanization of modern agriculture. The 1938 Massey-Harris Model 20 self-propelled combine, a designated landmark of American agricultural engineering, was the first commercially successful self-propelled combine to make its way through an American harvest.

1930s, 20th century, Henry Ford Museum, food, farms and farming, farming equipment, by Jim McCabe, agriculture

In the early 1920s, Tsuneji "Thomas" Sato (1882-1969) found himself in the middle of a Michigan lumber camp on the opposite side of the world from his birthplace in Japan. Working with precision and productiveness and, most importantly, personality, Sato served a hot meal to a group of vagabonds who, although weary from their travels, had no apparent reason to be weary at all. Sato knew that firsthand, as he and his co-workers had been the ones responsible for getting this party — and their extravagant caravan — over hills, across rivers and through the wilderness.

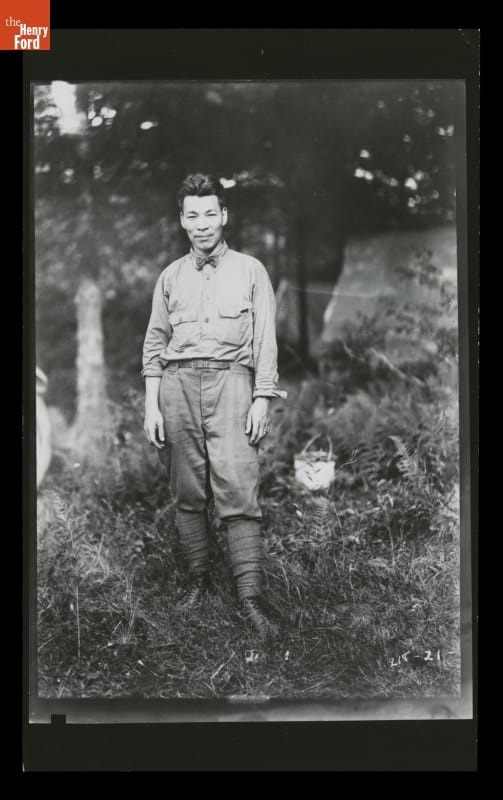

Tsuneji Sato, 1921. / THF127407

While the lumber camp was obscure, the camping party’s members certainly were not, as Sato’s employer was the man who needed the vast swaths of hardwood being extracted out of Michigan’s northern forests at this camp, and others, to feed his automobile manufacturing machine, Ford Motor Company. At the heart of the company’s brand recognition was the polarizing, do-it-yourself folk hero Henry Ford whose wealth contradicted his own populist ethos and whose life was wholly dependent on a group of people who made things happen for him. A group, for some time, that included Sato. So much so that Ford postponed this trip just to ensure that Sato could make it work around his own personal schedule.

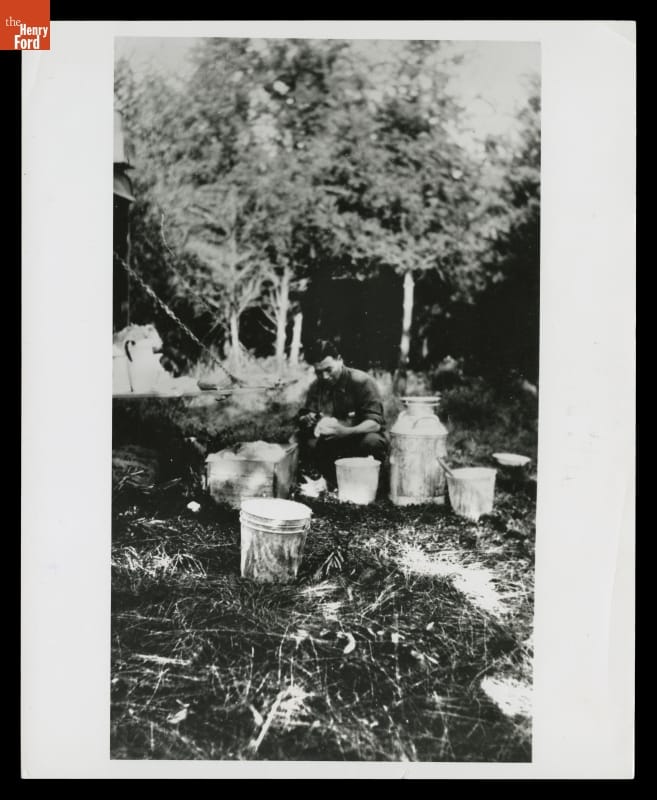

Tsuneji Sato preparing a meal at Sidnaw Lumber Camp in 1923. / THF127423

In some sense, the Fords were no different than other wealthy families of the early 20th century who had the means to staff their homes, preferring to hire domestic servants from a growing Japanese immigrant population generalized at the time as “polite, careful, clean, ambitious, and intelligent.” Japanese immigration to the United States had gradually increased over the late 1800s as the notoriously insular empire emerged from isolation and struggled with the abrupt pace of industrialization, regional war and a northern famine. By the early 1900s, hundreds, if not thousands, of Japanese immigrants were finding employment success in America’s household services sector, but a general spike in immigration began escalating a nativist angst among white Americans.

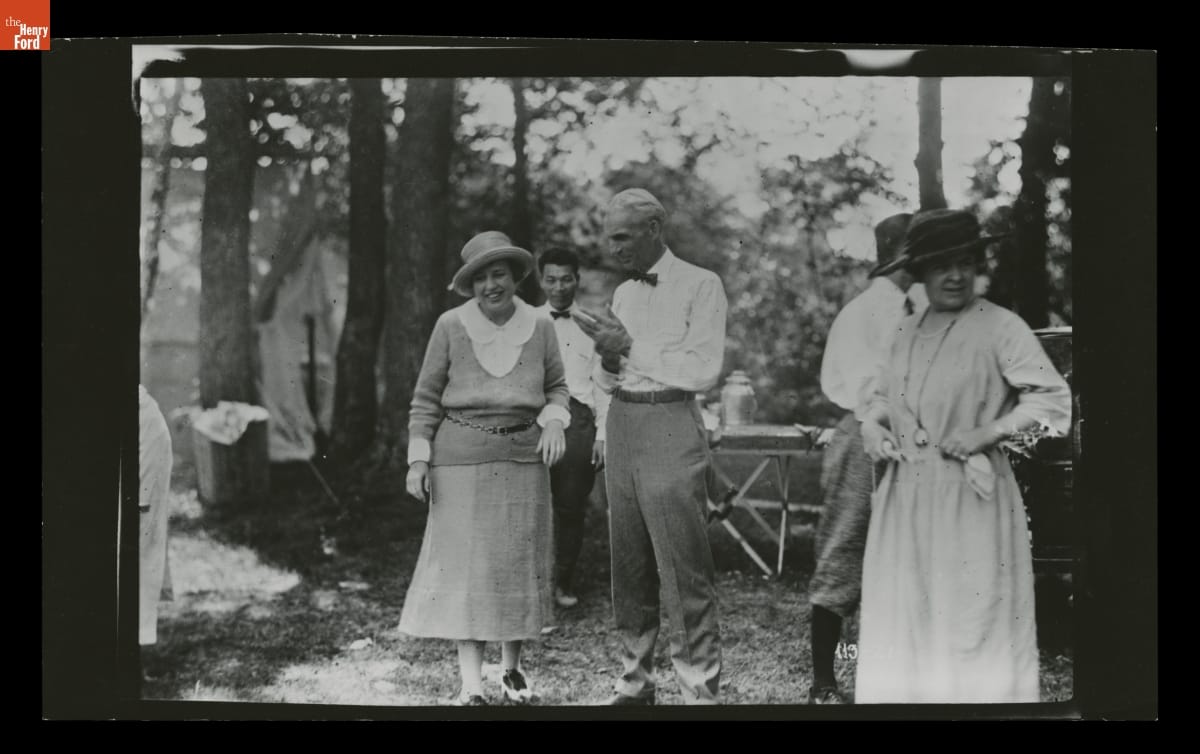

The Ford Family and Tsuneji Sato. Pictured left to right are Eleanor Ford, Sato, Henry Ford, Edsel Ford and Clara Ford on a 1921 camping trip in Maryland. / THF127405

A furor of anti-Asian discrimination and violence, especially on the West Coast where Asian American communities were expanding, eventually led to an informal agreement between President Theodore Roosevelt and Japan, known as the Gentleman’s Agreement of 1907-1908, which restricted immigration from Japan until the Immigration Act of 1924 ultimately banned immigration from Asian regions altogether. Despite increasing xenophobia and restrictions, Tsuneji’s brother Junjiro (1870-1957) left their hometown of Wakuya, located in Japan’s northern prefecture, Miyagi, and made his way to the United States in 1894. At some point in the next 20 years, his younger brother Tsuneji would join him.

Tsuneji and Junjiro Sato. Date unknown. Source: Courtesy of the Sato brothers' descendants.

Upon the completion of Henry and Clara Ford’s sprawling Fair Lane Estate in 1915, Clara Ford contacted the Japanese Reliable Employment Agency of New York City looking for help. The Fords' former Japanese domestic servants, a couple who had worked for them at previous homes, wanted more for their lives in America: their own house and the ability to chase their own dream. Henry Ford obliged and gave the husband a job at his Highland Park plant, leaving Clara to inquire for someone who was single and “not as attached.” What the Fords received in Tsuneji Sato, now with the adopted English name of Thomas, was someone highly regarded who had the charisma and work ethic that could keep up with the unusual demands of an automobile magnate’s family. Continue Reading

What We Wore: Shoes

From practical footwear to eye-catching fashion statements, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s current What We Wore exhibit is all about shoes. On display are 30 pairs of men’s, women’s and children’s shoes dating from the 1780s to the 2000s.

Each pair offers a bit of footwear history — and, for some perhaps, a familiar style once found in their own closet!

Shoes will be on display until May 24. Here’s a peek at a few examples.

Men’s Boudoir Slippers, 1855-1860 / THF31115

Men's embroidered slippers were very popular in the mid-1800s. Ladies magazines often included embroidery patterns for house slippers that a woman might make for her husband as a gift.

Men’s Wingtip Oxfords, 1945-1955, Gift of Richard Glenn / THF370088

The low-sided oxford came into fashion for men’s footwear in the 1910s, along with wingtips (a toe cap in the shape of a bird’s wing embellished with a perforated pattern). White shoes were for summer.

Reebok Pump AXT Cross-Training Shoes, circa 1990 / THF370066

In the 1970s, athletic shoes became big business as the popularity of running and more relaxed dress codes in workplaces and schools led to a boom in the market. Manufacturers developed high-tech features designed for more support and stability. Reebok introduced the Reebok Pump in 1990, a shoe that used inflatable chambers that pumped-up for a custom fit.

Women’s Shoes, 1785-1789, Gift of American Textile History Museum / THF370062

Before shoemaking became a mechanized industry in the mid-1800s, shoes were made by hand. Amos Boardman created these silk shoes — undoubtedly for a prosperous client— in one of the many small shoemaking home-shops that flourished in late 1700s New England.

Women's Boots, 1867, Gift of Cora D. Maggini, Worn by Angeline (Anna) Duckworth when she married Rufus Larkin in Posey County, Indiana, in September 1867 / THF158262

Sandals from ancient Greece or Rome inspired these 1860s shoes — footwear designed to reveal pretty-colored silk stockings beneath!

Women’s Platform Shoes, 1945-1950, Gift of American Textile History Museum, Donated to ATHM by Sharon and Phil Ferraguto / THF370078

Introduced in the late 1930s, platform shoes remained popular through the 1940s. These eye-catching examples sport cherry red, ivory and gray reptile leather.

Women’s Glitter Jelly Sandals, circa 1990 / THF172055

Jelly shoes were a favorite among young women in the 1980s and 1990s. Made of PVC plastic, the shoes came in a rainbow of colors. Sandals were the most popular.

Girls’ Slippers, circa 1850 / THF156007

In the mid-1800s, girls wore slippers with ribbon ties for formal occasions. For everyday? Low boots.

Boys’ Boots, circa 1865 / THF156008

Children’s clothing has increasingly included images that have appeal for a child. These are an early example — Civil War-era boots with a figure of a dashing Zouave soldier.

Saddle Oxfords, 1955-1965, Gift of Randolph C. and Nancy M. Carey / THF78930

The saddle shoe, with its contrasting color leather “saddle,” is a style icon. Worn by uniformed schoolkids since the 1930s and by “bobby soxer” teens in the 1940s and 1950s, the saddle shoe has an enduring link to youth culture.

Jeanine Head Miller is curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford.

What We Wore, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, by Jeanine Head Miller, 20th century

Carnegie Libraries: Democratizing Knowledge

The Carnegie library depicted on this ceramic vase was built in Syracuse, New York, in 1905, with a $200,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie. Designed by Syracuse architect James Randall, it still boasts its original spacious marble vestibule and grand curved marble staircase. / THF192213

When I was growing up, I loved to visit the library. My local library, in a repurposed 1920s-era mansion in an eastside suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, was a magical place — complete with niches, mysterious cupboards and a grand staircase. I had no familiarity with Carnegie libraries until the 1980s when, as a young museum curator, I visited the Port Huron (MI) Museum of Arts and History to consult on a log cabin located on the museum’s grounds. When the director showed me around the main museum, he proudly told me that it had once been a Carnegie library. The interior space was delightfully laid out in a rotunda shape with staircases and balconies.

The Carnegie library in Lebanon, Ohio — funded by a $10,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie and supplemented by locally raised funds — opened in 1908. A large addition was built in the 1980s. / Photograph by the author.

I later encountered Carnegie libraries in other towns — like Traverse City, Michigan (where the library was also repurposed as a museum) and Lebanon, Ohio (where it is still used as a library). The townspeople in these places similarly spoke with pride about the fact that these were Carnegie libraries.

Andrew Carnegie’s own bookplate, circa 1915, bears the biblical phrase “Let There Be Light,” which symbolized to him the illuminating qualities of books and knowledge. Carnegie sometimes requested that a rising sun and the phrase “Let There Be Light” be engraved near the entrance of a library that he funded. / THF291248

Carnegie libraries were the vision of Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919), a Scottish immigrant who was born poor but amassed an immense fortune from railroads, oil and steel. By the time he sold his Carnegie Steel Company for $250 million and retired, he was one of the wealthiest men in the world — perhaps the wealthiest.

As a youth working for a telegraph company in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), Carnegie was introduced to a Colonel James Anderson, who generously opened his private library to young workers wishing to borrow and read books. This inspired Carnegie so much that he promised himself that if he ever became wealthy, he would provide similar opportunities to eager and deserving workers.

In 1910, Denver, Colorado, opened its Central Library building, an elegant Greek temple design made possible by a grant from Andrew Carnegie. Between 1913 and 1920, Carnegie also underwrote the construction of the city’s first eight branch libraries, which came to a grand total of $230,000. This building was decommissioned in 1956 when a new Central Library opened. / THF628038

Indeed, when Carnegie retired a wealthy man, he devoted the rest of his life to philanthropy, giving away some $350 million — nearly 90% of his fortune — to a variety of charities. At the same time, he developed a philosophy about wealth and philanthropy, which he described in an 1889 essay entitled, “The Gospel of Wealth.” In this essay, he asserted that the wealthy should use their riches for “lasting good” to society. They should live without extravagance, provide moderately for their dependents and distribute the rest of their riches to benefit the welfare and happiness of the common man — meaning not just anyone, but those who helped themselves, those who were interested in improving their own lot in life.

This free public library, which was designed by McKim, Mead & White and opened in 1904, was located on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. It was aimed at the varied immigrant populations — German, Italian, Jewish, Polish and Ukrainian — who inhabited that part of the city. / THF38047

This philosophy paralleled that of Progressive-era reformers of the time, who attempted to “remedy” the challenges inherent in the tremendous increase of immigrants arriving in America. These reformers believed that libraries were important to arming the new immigrants with knowledge to help them rise in society, become better voters by resisting the lure of dishonest politicians and avoid such unwholesome pursuits as drinking and gambling.

Wealthy, educated citizens often amassed private libraries for their own use. In this photograph, William J. Carr, justice of the Supreme Court of Kings County, New York, poses in front of his massive book collection. / THF38611

Free public libraries began to spread during the early 20th century, coinciding with new town developments. Before that time, most book collections were either privately owned, accessible by paid subscription or haphazardly stored in such public buildings as churches, post offices or city halls. But, although townspeople were high on ideals and ambition, these public libraries usually lagged behind in development, as money was tight, book collections were lacking and establishing places for reading just seemed to be a lower priority than such essential city services as public transportation, sanitation and schools.

When the citizens of Canton, Ohio, received Carnegie funding for a new library building, they enthusiastically held a design competition. Canton architect Guy Tilden won the competition and designed a stately new library, which opened in 1905. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. / THF289036

Enter Andrew Carnegie, armed with happy memories of times spent as a youth in Colonel Anderson’s library and committed to helping those who wanted to improve their own lives. The first of his funded libraries opened in 1889, in Braddock, Pennsylvania, home to a Carnegie steelworks. This was followed by a library in Carnegie’s own hometown of Allegheny.

Between 1886 and 1919, Andrew Carnegie donated more than $40 million to 1,679 new library buildings in communities of all sizes across America. Carnegie libraries were constructed in 46 states — with Indiana leading the way (165), followed by California (142), Ohio (111), New York (106), Illinois (106) and Iowa (101). Carnegie also funded libraries in other countries — the first being in his birthplace of Dunfermline, Scotland.

As Detroit grew by leaps and bounds in the early 20th century, the existing library building quickly outgrew its capacity. In 1910, the city accepted funds from Andrew Carnegie to build a new library to be situated along rapidly expanding Woodward Avenue. New York City architect Cass Gilbert (designer of the famed Woolworth Building) won the design competition for the new building, which opened in 1921. North and south wings were added in 1963. / THF119073

Towns had to apply to receive funding for a Carnegie library. In their applications, townspeople had to promise that their town owned the land on which the library would be built and that they would commit to the library’s ongoing maintenance and staffing. The architectural styles of the buildings typically followed popular building styles of the time and were often the result of local design competitions. In many small towns, the Carnegie library stood out as the most imposing structure, symbolizing that community’s dreams of prosperity and hopes for the future.

Although a free public library had existed in Newark, New Jersey, since 1884, this building, which opened in 1901, featured the new innovation of open stacks. / THF38387

A unique feature inside these libraries was "open stack" shelving that encouraged browsing. (Before, a clerk or librarian would retrieve requested books from “closed stacks.”) The libraries also tended to be open in design so that a librarian stationed at a central desk could keep a watchful eye over the entire library. Unfortunately, over time, staffing and maintenance did become an issue in many towns, as city planners were thrilled to receive a grant to build their library but then found themselves strapped for funds to support and maintain it.

In 1905, Andrew Carnegie donated an initial $260,000 to build a central library and three branch libraries in Springfield, Massachusetts (with enthusiastic contributions from local citizens, he increased his donations twice). An Italian Renaissance Revival-style design was chosen for the building, which opened in 1912 and featured a bronze bust of Andrew Carnegie in the central rotunda. In 1974, the library was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. / THF628058

Some people questioned Andrew Carnegie’s motives in funding these libraries. In 1892, Carnegie refused to end violence caused by strikebreakers at his company's Homestead Steel Works, forever staining his reputation. People criticized him for being ruthless, for funding libraries as a personal monument, for funding institutions that focused on the poor, or for focusing myopically on libraries as a panacea to society’s ills. Black activists criticized him for reinforcing Jim Crow (segregationist) policies while white racists accused him of potentially forcing integration into towns that strictly adhered to Jim Crow laws.

Iowa City, Iowa, was undergoing extensive growth at the turn of the century, and the Library Board of Trustees saw the wisdom of building a permanent home for its library. The board sent an inquiry to Andrew Carnegie during the summer of 1901 and was awarded a $25,000 grant (with an additional $10,000 the following year) for the library’s construction. The library opened in 1904. / THF628004

In the end, despite questions and criticism, large cities and small towns alike could not resist the lure of outside funding for a public library. To those who did get Carnegie funding to build a free public library, their libraries were, and have remained, sources of civic pride, epitomizing the sort of democratizing spirit that pervaded American communities in the early 20th century.

Donna R. Braden is senior curator and curator of public life at The Henry Ford.

Ferris Bueller’s Faux Ferrari: A Replica with Real History

Like an actor cast in a role, this 1985 Modena Spyder California was chosen to play the part of a Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder in the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. / Photo by Matt Anderson

For those who haven’t visited Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in recent months, we have a wonderful new display space created in partnership with the Hagerty Drivers Foundation. Each year, we’ll share a couple of significant automobiles included on the foundation’s National Historic Vehicle Register. The (currently) 32 vehicles on the register each made a lasting mark on American history—whether through influence on design or engineering, success on the race track, participation in larger national stories, or starring roles on the silver screen.

Our first display vehicle is Hollywood through and through. It’s a “1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder” (those quotes are intentional) used in the 1986 Gen-X classic Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Those who’ve seen the film know that the car is a crucial part of the plot—ferrying Ferris, Sloane Peterson, and Cameron Frye around Chicago; threatening to expose their secret skip day; and forcing a difficult conversation between Cameron and his emotionally distant father.

In true movie fashion, though, not all is what it appears to be.

This 1958 Ferrari 250 GT California is the real thing, as featured in Henry Ford Museum’s Sports Cars in Review exhibit in 1965. / THF139028

The Ferrari 250 is among the most desirable collector cars in the world. GT street versions sell at auction for millions of dollars. And GTO competition variants—well, the sky’s the limit. Even in the mid-1980s, these autos were too pricey for film work—particularly when the plot calls for the car to be (spoiler alert) destroyed. Instead, Ferris Bueller director John Hughes commissioned three replicas for the shoot: two functional cars used for most scenes, and a non-runner destined to fly out the back of Mr. Frye’s suburban Chicago garage.

Replica cars were nothing new in the 1980s. For years, enterprising manufacturers had been offering copies of collector cars that were no longer in production and too expensive for most enthusiasts. The coveted Duesenberg Model J is a prime example, having been copied by replica manufacturers for decades. Some replica cars were more about convenience than cost. Glassic Industries of West Palm Beach, Florida, produced fiberglass-bodied copies of the Ford Model A with available niceties like automatic transmissions and tape decks. Occasionally, the line between “real” and “replica” got blurry. Continuation cars like the Avanti II (based on Studebaker’s original) or post-1960s Shelby Cobras (based on Carroll Shelby’s racing sports cars) were sometimes built with formal permission or participation from the original automakers.

So, if the Ferris Bueller car at The Henry Ford isn’t a real Ferrari, then what is it?

The replica’s builder, Modena Design & Development, was founded in the early 1980s by Californians Neil Glassmoyer and Mark Goyette. When John Hughes read about Modena in a car magazine, he called the firm. As the story goes, Glassmoyer initially hung up on the famous writer/director—believing that it had to be a prank. Hughes phoned again, and Modena found itself with a desirable movie commission. Paramount Pictures, the studio behind Ferris Bueller, leased one car and bought two others.

The Modena replicas featured steel-tube frames and Ferrari-inspired design cues like hood scoops, fender vents, and raked windshields. While the genuine Ferrari bodies used a blend of steel and aluminum components, Modena’s bodies were formed from fiberglass—purportedly based on a British MG body and then fine-tuned for a more Ferrari-like appearance.

The replica Ferrari’s V-8 was sourced from a 1974 Ford Torino, not too different from these 1973 models. / THF232097

The most obvious differences were under the cars’ skin. Rather than a 180-cubic-inch Ferrari V-12, the Modena at The Henry Ford features a 302-cubic-inch Ford V-8 (originally sourced from a 1974 Ford Torino). While the Ford engine was rated at 135 horsepower from the factory, this one has been rebuilt and refined—surely capable of greater output now. And instead of the original Ferrari’s four-speed manual gearbox, the Modena has a Ford-built three-speed automatic transmission. (According to lore, actor Matthew Broderick wasn’t comfortable driving a manual.)

After filming wrapped, the leased car was sent back to Modena’s El Cajon, California, facility. After some work to repair damage from a stunt scene, the car was sold to the first in a series of private owners. By 2003, this beloved piece of faux Italiana/genuine Americana had been relocated to the United Kingdom. The current owner purchased it at auction in 2010 and repatriated the car to the United States. The Modena was much modified over the years, so the current owner had it carefully restored and returned to its on-screen appearance—as you see it today.

Imitation can be the sincerest form of flattery, but it can also be the quickest route to a lawsuit. Following the release of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Ferrari sued Modena Design & Development (along with other replica builders). The matter was settled out of court when Modena agreed to make some minor changes per the Italian automaker’s specifications. Replica production then resumed for a few more years.

The Modena Spyder California may not be a real Ferrari, but it’s certainly a real pop-culture icon. That’s reason enough to include it on the National Historic Vehicle Register, and to celebrate it at The Henry Ford.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford Museum, Europe, 1980s, 20th century, Illinois, California, by Matt Anderson, popular culture, movies, cars

Leo Goossen

Supercharger Assembly Drawing of Offenhauser Engine by Leo Goossen, April 21, 1934 / THF175170

Leo Goossen was an automotive draftsman, engineer, and one of the most influential engine designers in American auto racing. In a presentation from our monthly History Outside the Box series on Instagram earlier this year, Processing Archivist Janice Unger recognized Goossen’s 130th birthday with a quick biography and look at some of Goossen’s work from our collections. If you missed it on Insta, you can watch below.

California, 20th century, racing, race cars, Michigan, History Outside the Box, engines, engineering, drawings, cars, by Janice Unger, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

Designs for Aging: New Takes on Old Forms

Designs for Aging: New Takes on Old Forms, a temporary pop-up exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation from August through October 2022 / THF191476

A chair, a cane, a vegetable peeler.

These are not new forms. Versions of these objects have existed for hundreds of years and have even worked well enough for many people.

But did these objects work well for all people?

This is the question that Universal Design asks. As the industrial design discipline has evolved, designers’ awareness of needs beyond those of “the average person”—such as children, those with disabilities, and older adults—has grown. The practice of Universal Design advocates for the inclusion of a range of bodies and abilities in the design of objects.

Each of the objects below represent the story of a designer working to transform an ordinary object into one that performs better for a group whose needs are often overlooked: older adults.

The results are products that work better for all of us.

Disability Rights & the “Graying of America”

The American disability rights movement gained traction and national attention by the mid-1970s. Activists advocated for equitable care for all people and framed accessibility as a civil rights issue—modeling their language after the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

At the same time, concerns were raised about the future impacts of the baby boom and decreasing fertility rates: soon, the media reported, elderly people would outnumber children.

The disability rights movement and the “graying of America” converged and designers began to explore what part design could play in creating equitable and accessible environments for older adults.

Notal Program, 1979, page 6 / THF702602

Herman Miller’s Projects for Aging

In the 1970s, Michigan-based furniture company Herman Miller embarked upon exploratory design projects for the elderly.

The Notal project was their first foray into design specifically for older adults, researching how their day-to-day lives were affected by ill-suited environments.

The MetaForm project was established in the mid-1980s. The project’s leaders hoped to reimagine whole environments to best suit the challenges that accompany aging—enabling people to “age in place,” at home instead of an institution. A variety of high-profile consultants and designers were hired to explore solutions for five specific areas—sleeping, long-term sitting, food preparation, material handling, and personal hygiene.

Woman in Motion Study with Prototype Sarah Chair, 1987-1991 / THF702658

The Sarah Chair

Herman Miller designers Don Chadwick and Bill Stumpf were tasked with creating a chair that would accommodate long-term sitting for the MetaForm project.

Stumpf had deep knowledge of ergonomics; Chadwick was especially adept at solving problems of form. Their “Sarah Chair” incorporated ideas to serve aging bodies, including an advanced tilt mechanism to aid users in getting into and out of the chair without losing balance.

Despite years of research, user testing, and prototyping, Herman Miller canceled MetaForm in 1991, primarily due to the challenges of marketing high-end furniture to older adults.

Stumpf and Chadwick applied the lessons learned from the Sarah Chair toward another group of people who sat for long periods: office workers. The Aeron Chair was introduced in 1994 to immediate and lasting acclaim.

Prototype Sarah Lounge & Rocker Combination Chair, 1987-1991 / THF191319

OXO Good Grips

In the 1980s, Sam and Betsey Farber had retired from a long career in the cookware industry and were enjoying travel. While on vacation, Betsey was trying to peel an apple but was having difficulty due to the arthritis in her hands. The traditional vegetable peeler she was using was difficult to grip, especially when applying force. Sam and Betsey realized there was an opportunity to improve this object and called a friend, Davin Stowell of design consultancy Smart Design, and asked him to prototype an easier-to-user peeler.

The OXO Good Grips Swivel Peeler was introduced in 1990. Despite its cost (nearly triple the traditional peeler), it sold well. This relatively simple improvement to a classic tool increased usability for a wide range of people. The OXO Good Grips line of tools now numbers in the hundreds.

OXO Good Grips Swivel Peeler, 2022 / THF191162

Patricia Moore: Designer and Gerontologist

As a young industrial designer working for the firm of design legend Raymond Loewy, Patricia Moore often challenged her superiors to design more accessibly, for a wider variety of body types and abilities. Looking to better understand the challenges of an elderly person, Moore employed a professional makeup artist and transformed herself into an 80-year-old woman using a latex mask and custom prosthetics. She even put baby oil in her eyes to blur her vision, stuffed wax in her ears to muffle sound, and bound her body to restrict movement. She then went out into the world—observing, interacting, and connecting with people as an elderly woman—with the ultimate goal of using these experiences to help design better products for aging adults.

Moore disguised herself for over three years, conducting research and becoming a sought-after expert in design for aging populations. She has spent decades consulting on projects, including Herman Miller’s MetaForm and OXO Good Grips.

Disguised!, 1985 / THF703274

Michael Graves’s Canes

Architect and industrial designer Michael Graves developed an interest in Universal Design and the healthcare industry after an infection left him paralyzed from the waist down in 2003. In the years after his own ability shift, Graves redesigned the utilitarian objects that become indispensable with age and disability—objects that didn't hold the attention of most mainstream industrial designers. He focused on the cane as an object particularly ripe for revision, prototyping numerous ergonomic handles and experimenting with the grip.

Cane Handle Models on Display Board, 2014-2015 / THF191163

The canes that Graves designed, as well as those created by his design firm after his death in 2015, are adaptable to bodies as well as lifestyles. They are lightweight, available in numerous colors, adjustable to accommodate differing heights, and foldable for storage.

Quick Fold Cane, 2021 / THF191154

Michael Graves Design & Stryker

Michael Graves Design teamed up with Stryker, a medical technologies company, to reimagine the hospital patient’s experience. Spurred by one of his many extended hospital stays, Michael Graves remarked, “It was far too ugly for me to die in there!”

Stryker Prime TC Transport Chair, 2013 / THF188699

Graves redesigned the wheelchair—a chair that had seen little change since the 1930s—as well patient room furniture. User comfort was the ultimate focus. The objects Graves designed feature adjustable components, easy maneuverability, and intuitive operation, as well as quality finishes and his signature injection of color.

Katherine White is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford. A temporary exhibit, Designs for Aging: New Takes on Old Forms, curated by Katherine, was on view in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation from August–October 2022. The content of the exhibition is replicated in this post.

Additional Readings:

- Table, Used as a Writing Desk by Mark Twain, 1830-1860

- Creatives of Clay and Wood

- Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices

- Women Design: Peggy Ann Mack

21st century, 20th century, home life, Herman Miller, healthcare, furnishings, design, by Katherine White

The Grand Army of the Republic and Memorial Day

Members of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) Visiting Mount Vernon, September 21, 1892 / THF254036

The Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) was a fraternal society founded in 1866 for Civil War veterans from the Union Army. Earlier this year, Collections Specialist Laura Myles shared some artifacts from our collections related to the G.A.R., and also explained their relationship with Memorial Day (originally called Decoration Day), as part of our History Outside the Box series on The Henry Ford’s Instagram channel. On the first Friday of every month, our collections experts share stories from our collection on Instagram—but if you missed this particular episode, you can watch it below.

Continue Reading

20th century, 19th century, veterans, holidays, History Outside the Box, Grand Army of the Republic, Civil War, by Laura Myles, by Ellice Engdahl

Bonnie Cashin: Innovative and Influential

Our latest installation of What We Wore: Bonnie Cashin. / THF191461

The current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation features clothing by Bonnie Cashin. American designer Bonnie Cashin’s ideas, radical when introduced, have become timeless.

Who was Bonnie Cashin? An inscription in her senior yearbook provided a hint of things to come: “To a kid with spark—may you set the world on fire.” She did. By the 1950s, Cashin had become “a mother of American sportswear” and one of the most influential fashion designers of the 20th century.

Born in 1908 in California, Bonnie Cashin apprenticed in her mother’s custom dress shop. At 16, she began designing chorus costumes for a Hollywood theater. Next stop—the Roxy Theatre in New York City, where the 25-year-old was the sole designer. The street clothes Cashin designed for a fashion-themed revue led to a job at the prestigious ready-to-wear firm Adler & Adler in 1937. Cashin left for California in 1943, where she spent six years at 20th Century Fox, designing costumes for approximately 60 films.

Cashin’s designs for the 1944 movie Laura were the most influential of her 20th Century Fox creations. Motion pictures of the 1940s tended to showcase female stars as wealthy and glamorous women. Cashin’s designs for actress Gene Tierney suggested clothing chosen by the character of Laura herself, rather than costumes worn for an actress’s role. A revolutionary concept for the time, the garments reflected Cashin's real-life views. / THF700871

Cashin and actress Olivia de Haviland look over costumes created for the motion picture The Snake Pit in 1948. / THF703254

In 1949, back in New York, Cashin created her first ready-to-wear collection under her own name. Cashin designed for “the woman who is always on the go, who is doing something.” She introduced the concept of layering, with each piece designed to work in an ensemble, alone, and in different combinations. The fashion world took notice. In 1950, Cashin won both the prestigious Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award and the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award.

This 1952 ad dates from the year Bonnie Cashin opened her own design studio. It captures the spirit of Cashin’s intended customers—women always on the go. / THF701655

In 1952, Cashin opened her own one-woman firm, Bonnie Cashin Designs. Cashin insisted on total creative control as she worked with the manufacturers who produced her designs. Cashin chose craftsmanship over commercial success. She never wavered in her artistic vision—functional simplicity and elegant solutions.

Jacket (Wool, Brown Leather Binding, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1970, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188918

Trousers (Suede), 1955–1960, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188947

Many Cashin designs were practical solutions to problems she herself experienced. Her tailored poncho was born after she cut a hole in a blanket to cope with temperature fluctuations while driving her convertible through the Hollywood Hills.

Coat (Mohair, Suede Bindings, Brass Clip Closure), 1955–1964, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188928

Sweater (Cashmere, Brass Buttons), 1955–1964, Designed by Bonnie Cashin, New York City, and Made by Ballantyne, Innerleithen and Peebles, Scotland. / THF188908

Trousers (Leather, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1970, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188945

Cashin is most well-known for her innovative use of leather, mohair, suede, knits, and nubby fabric, as well as heavy hardware used as fastenings. Cashin had a deep love of color and texture—she personally selected, designed, or commissioned her fabrics.

In this 1972 ad for Singer sewing machines, examples of Bonnie Cashin’s favored textiles—suede, leather, knits, and nubby tweeds—appear on the shelves behind her. / THF700873

Traveling widely during her career, Cashin closely studied the traditional clothing of other cultures. Her international focus and attention to refining traditional shapes down to their most modern and mobile forms led to her distinctive “Cashin Look.”

Jacket (Mohair Bouclé, Leather Bindings, Brass Sweater Guard Closure), about 1965, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City; Fabric Made by Bernat Klein, Galashiels, Scotland. / THF188913

Bonnie Cashin created dazzling costumes for the stage and screen—then excelled at exquisite minimalism in her sportwear. The intersection? Cashin’s garments always moved with the wearer and were designed to be set against a backdrop—whether a theatrical scene or contemporary life.

Coat (Wool, Leather Binding), 1965–1972, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188933

Trousers (Leather, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1972, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188943

Jacket (Leather, Brass Toggle Closures), 1965–1972, Designed by Bonnie Cashin and Made by Philip Sills & Co., New York City. / THF188938

Innovative and influential, Cashin continued to design until 1985. Following her death in 2000, among the handwritten notes jotted on scraps of paper in her apartment was one that read, “How nice for one voice to ignite the imaginations of others.”

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, California, New York, women's history, What We Wore, movies, making, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, entrepreneurship, design, by Jeanine Head Miller