What If

A triumph of human ingenuity, the Allegheny locomotive pushed the limits of what steam power could do just before the Age of Steam ended. There was no higher development in steam. Eugene L. Huddleston & Thomas W. Dixon, Jr.

A Call for Steam Power Invention

As America emerged from the Great Depression, executives of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway went searching for the mightiest steam locomotive they could find. With the country’s growing demand for coal—especially for industry in the Midwest, where the fuel was used to heat, cool, and power many factories—C&O leaders naturally wanted to increase the efficiency of their coal-carrying freight trains, especially those traversing their most profitable line, the Allegheny Subdivision.

Allegheny Steam Locomotive, 1941

Artifact

Steam locomotive

Date Made

1941

Summary

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway's massive Allegheny, introduced in 1941, represents the peak of steam railroad technology. Among the largest and most powerful steam locomotives ever built, it weighed 1.2 million pounds with its tender and could generate 7,500 horsepower. Just 11 years later, C&O began pulling these giants from service. Diesel-electric locomotives proved more flexible and less expensive.

Creators

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

56.50.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Chesapeake and Ohio Railway.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Allegheny Steam Locomotive, 1941

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Just 80 miles long, this short but steep two-track mainline running through West Virginia coal country posed a monumental performance challenge for designers. C&O executives wanted an immensely powerful locomotive capable of hauling 160 loaded hoppers, a train 1.25 miles in length and weighing more than 10,000 tons (cargo, locomotive, fuel, and all). They wanted the engine to be fast, moving maximum tonnage at speeds of 40 to 50 miles per hour. And they wanted freight dragged up and down some of the steepest, curviest tracks ever built in the rugged western-central portion of the Appalachian Mountain Range.

Firing Up: The Beginning of 'Modern' Steam Locomotion

At the time, the American railroad industry was dominated by three locomotive builders: Alco, Baldwin, and Lima. Although Lima was the smallest of the three, the company’s chief locomotive designer—a Cornell-educated engineer named Will Woodward—was an industry rock star. More than a decade earlier, he had established Lima’s reputation as the Cadillac of locomotive builders by ushering in what many railroad historians consider the modern age of steam with his “Super Power” invention.

A breakthrough in efficient horsepower performance, Woodward’s 1925 locomotive could generate more steam power per weight than any engine ever built. It could do this because Woodward designed a firebox twice the size of conventional units. And then he exploited the firebox’s increase in energy production by finding ways for his engine to more efficiently use steam by as much as 30 percent. This was a radical departure from the direction other engineers were exploring.

To support his supersized furnace, Woodward added something else no one had ever seen before: a four-wheel trailing truck. These four wheels are announced anytime railroad insiders talk about the “2-8-4” wheel arrangement of Woodward’s first Super Power locomotive (the “2” and “8” refer to its two leading wheels and eight driving wheels). “No other steam locomotive built after World War I had such a remarkable, lasting, and beneficial effect upon the American scene,” historian David P. Morgan wrote in his book, "Steam's Finest Hour," “‘Modern’ no longer meant the addition of another driving axle and more adhesive weight; modern meant horsepower – i.e., power at speed.”

The Long Approach: Getting the Rails Ready

Like many great inventions, Woodward’s breakthrough design sparked a movement of implementation and refinement by other engineers seeking to make improvements and build ever more fuel-efficient, high-speed trains. But not long after the Super Power era started, the Great Depression crippled manufacturing across the country and the market for newer, faster locomotives essentially disappeared. Alco, Baldwin, and Lima struggled to stay in business.

Things were not so dire at the C&O. Despite the country’s economic crisis, there was still a demand for the Appalachian bituminous coal coming out of the mines in West Virginia. Which is why C&O executives were able to make significant investments during the 1930s to upgrade the Allegheny Subdivision line. The company spent millions to bore new tunnels, add double track, rebuild bridges, and upgrade the weight of its rail. The high unemployment rate also meant they were able to hire men to do this work for modest pay. When the economy began to recover, the C&O’s rails across the Allegheny Mountains were ready for faster trains.

Up north in Ohio, the next generation of Lima engineers had been using the slow years of the Depression to draft blueprints for a bold new steam locomotive. In 1940, they approached the C&O with their proposal. It was just the kind of engine C&O executives had been looking for.

The Birth of a Locomotive Legend

Weighing 600 tons and measuring nearly 17 feet tall and 125 feet long, Lima’s new locomotive was definitively the world’s tallest and heaviest, possibly the fastest and most powerful. It was outfitted with many new improvements, including 67” diameter driving wheels for faster speeds, an automated coal stoker to relieve the fireman from having to manually feed the giant furnace, and a bigger boiler capable of generating a tremendous amount of steam pressure (260 psi) which, when released into the cylinders by opening the throttle, created extraordinary piston thrust. It also had smaller modern touches, such as an automated bell-ringer and whistle.

Woodward, then in his sixties, was no longer working at Lima, but his successors’ locomotive reflected the principles of his pioneering design, including a giant firebox. Measuring 135 square feet (35 square feet larger than his original), this new furnace was supported by an even bigger trailing truck. Its new wheel arrangement was 2-6-6-6: two leading wheels, two sets of six driving wheels, and six trailing wheels. “That’s right,” one awe-struck editor for Railroad Magazine remarked about the design. “A six wheel trailing truck.”

C&O placed an initial order for 10 locomotives, paying $230,633 apiece. The engines were designated Class H-8, assigned road numbers 1600 through 1609, and given the name "Allegheny" in honor of the mountains through which they would run. The Lima crews started up production, and it took more than a year before the first locomotives were ready to leave the shop. Until that day arrived, many questions remained. “It looked good on the drawing board,” one observer remarked. “But how will it stand up in actual use?”

Ascent to the Top: Exploring the Limits of Steam Power

In December 1941, the first 2-6-6-6 locomotives shipped east. Although they were built expressly for the Allegheny crossing, the trains were put into service hauling coal from West Virginia to many destinations along the Atlantic seacoast and the Midwest, from Richmond, Virginia, to Toledo, Ohio. The new fleet was quickly declared Lima’s finest.

Fueled by 25 tons of coal and 25,000 gallons of water carried in its tender, the locomotive recorded unprecedented performances on test runs. But these records (pulling 160 loads of coal weighing 14,000 tons; producing 7,498 maximum drawbar horsepower at a speed of 46 mph) were set on C&O tracks in Kentucky and Ohio. For reasons still debated, C&O executives did not push their new locomotives to maximum horsepower and speed limits on the mountainous tracks for which they were designed. In fact, on the Allegheny crossing, the 2-6-6-6s were often run at cautiously slow speeds, sometimes only 15 mph.

Conservative operating policies and safety concerns are often cited as reasons. Another factor may have been that just as the fleet was starting operation, the country entered another period of economic turmoil—this time, caused by America’s entry into the Second World War. Some of the Allegheny locomotives were taken out of freight service and assigned to passenger trains to carry troops. By the end of the war, the C&O had a new owner: Robert Ralph “R.R.” Young, a former stockbroker who was known as one of the “most ruthless financial strategists in the U.S.,” chose not to exploit the 2-6-6-6’s full potential. Future C&O owners never did either.

Most railroad historians agree the Allegheny was the world’s greatest steam locomotive: the tallest, heaviest, and most powerful. But they—and all of us—are also left to wonder what if these magnificent locomotives hadn't been scrapped so soon?

Lessons from the Summit

The French author Émile Zola was not the first to suggest that a steam locomotive has “a soul of its own,” but his words are perhaps the most famous. His poetic expression captures the longing many railroad enthusiasts felt, and still feel, at the sudden disappearance of these historic locomotives from the rails. The C&O purchased a total of 60 Allegheny locomotives. But by 1956, after only 15 years in service, they were all removed from the C&O tracks. All but two engines were scrapped as the industry adopted more efficient diesel locomotives.

No. 1601, the second Allegheny made by Lima workers in 1940, is now housed inside Henry Ford Museum. To stand beside it today is to marvel not only at its immense size, but at its thoughtful design. Every part, pipe, and tube fits together with astonishing precision.

To appreciate the Allegheny’s artistry, consider this: Climb up into the cab, just as the engineer and fireman did years ago, and let your imagination hop on an eastbound coal run out of Hinton, West Virginia. Here you are, standing just a few feet from the giant firebox, the engine straining as the engineer opens the throttle, pulling the big load above the New River Gorge with a second Allegheny engine pushing from the rear. Not far from Hinton, the train enters the darkness of Big Bend Tunnel, the engine’s two sets of articulated driving wheels pivoting independently, negotiating the tight curves. Up, up, up the train climbs for another forty miles, snaking through more tunnels and winding passages, until at last it crosses the 2,072-foot summit.

The views from the top reveal majestic Appalachian country, valleys all around dug deep by glaciers millions of years ago, creating some of the oldest mountains in the world. Before the locomotive drops down the other side toward Clifton Forge (a descent so steep it will cause the brakes to smoke, as the engineer works to keep the tremendous weight of the train under control), pause your imagination to reflect on this remarkable journey. The way is paved with great inventors and innovations, achievements in the era of steam power that started long before Will Woodward first conceived of Super Power. To locate the very beginning, you must go back three hundred years to when a British inventor named Thomas Newcomen discovered how to use steam pressure inside a cylinder to push down a piston. This was the world’s first steam engine, designed around 1712 and used to pump water out of a mine.

The Allegheny was the latest—and, as it turned out, last—evolution of this steam technology, a machine made possible not simply by an explosive new design from one inventor but by generations of innovators building on the work of those who came before. It was also a machine made possible by a unique American combination of economic, political, and labor conditions. Now at rest on the museum’s teakwood floor, the Allegheny stands as a reminder of the extraordinary forces that came together to make one of the world’s greatest steam-powered machines, a monument to human achievement.

Browse Collections

"Chimney Rock and New River Canyon near Fayette, W. Va.," circa 1913

Artifact

Postcard

Date Made

circa 1913

Summary

From 1895 to 1924, the Detroit Publishing Company was one of the major image publishers in the world. It had a wide-ranging stock of original photographs, many of which were colored using the company's patented "Phostint" process. Popular "Phostint" postcards, the Detroit Publishing Company claimed, were delicately "executed in Nature's Coloring" to be truthful, tasteful, beautiful, and educational.

Place of Creation

Keywords

United States, West Virginia, Fayette county

Object ID

37.102.162

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

"Chimney Rock and New River Canyon near Fayette, W. Va.," circa 1913

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

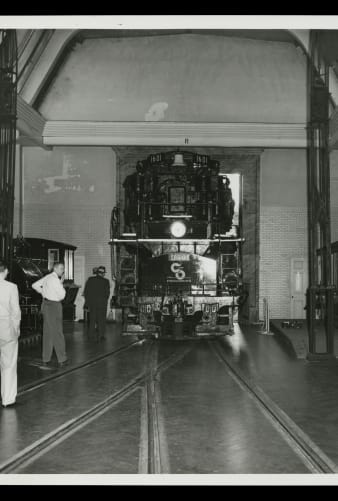

Third Attempt to Move the "Allegeheny" Locomotive into Henry Ford Museum, September 6, 1956

Artifact

Photographic print

Date Made

06 September 1956

Summary

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway 2-6-6-6 Allegheny locomotive is one of the most popular artifacts in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. It was also one of the most difficult to install. An exterior door to the building had to be enlarged and parts had to be removed from the locomotive before it could be squeezed into the museum.

Place of Creation

Object ID

EI.1929.P.B.13540

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

On Exhibit

Not on exhibit to the public.

Related Objects

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Third Attempt to Move the "Allegeheny" Locomotive into Henry Ford Museum, September 6, 1956

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Newcomen Engine, circa 1750

Artifact

Steam engine (Engine)

Date Made

circa 1750

Summary

This is the oldest known surviving steam engine in the world. Named for its inventor Thomas Newcomen, the engine converted chemical energy in the fuel into useful mechanical work. Its early history is not known, but it was used to pump water out of the Cannel mine in the Lancashire coalfields of England in about 1765. The engine was presented to Henry Ford in 1929.

Place of Creation

Keywords

United Kingdom, England, Greater Manchester, Ashton under Lyne

Object ID

29.1506.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Earl of Stamford Trustees.

Related Objects

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Newcomen Engine, circa 1750

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Allegheny Steam Locomotive, 1941

Artifact

Steam locomotive

Date Made

1941

Summary

The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway's massive Allegheny, introduced in 1941, represents the peak of steam railroad technology. Among the largest and most powerful steam locomotives ever built, it weighed 1.2 million pounds with its tender and could generate 7,500 horsepower. Just 11 years later, C&O began pulling these giants from service. Diesel-electric locomotives proved more flexible and less expensive.

Creators

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

56.50.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Chesapeake and Ohio Railway.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Allegheny Steam Locomotive, 1941

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Discussion Questions

- Do you think there was as single inventor or multiple inventors behind the success of the Allegheny locomotive?

- Can you name three things that made the Allegheny unlike other steam locomotive at the time?

- What problem was the Allegenhy locomotive trying to solve for owners of the C&O railraod?

- Can you think of a problem you’d like to solve in the world today that would build on the work of innovators from the past?

Fuel Your Enthusiasm

The Henry Ford aims to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic artifacts, stories and lives from America’s tradition of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation. Connect to more great educational resources: