Dr. Sullivan Jackson: Saxophonist

Music is a part of the Jackson family story, from the piano lessons that first brought young Richie Jean Sherrod soon-to-be-Jackson and young Coretta Scott soon-to-be-King together to the family's music room. In fact, Dr. Sullivan Jackson played tenor saxophone prior to his career as a dentist serving Selma's Black community. Dr. Jackson's time as a musician in the mid-1940s to the early 1950s allowed him to participate in Black American music cultural changes.

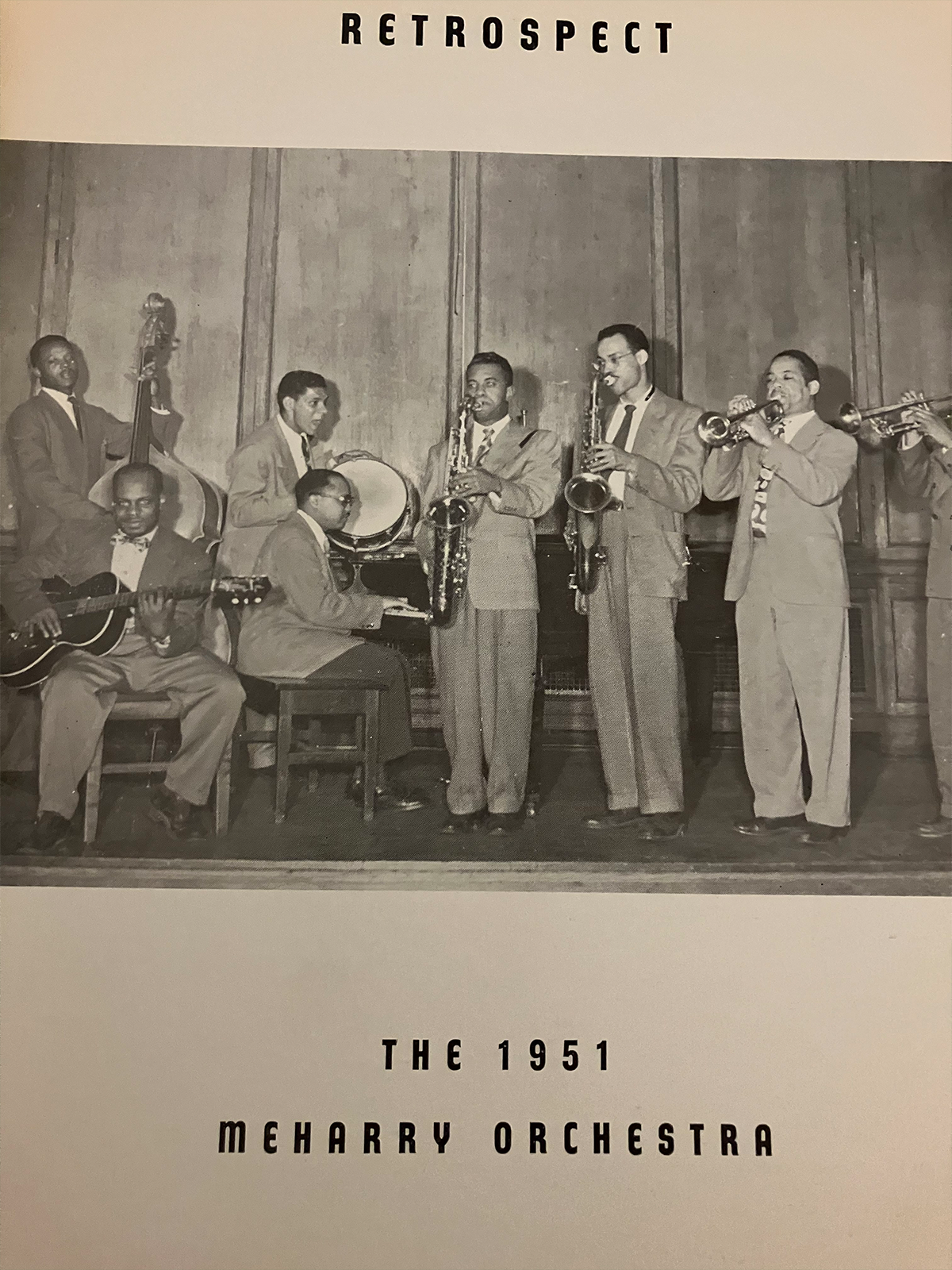

This picture of the Meharry Medical College Orchestra from the 1951 Meharrian yearbook shows Dr. Sullivan Jackson (center) playing the saxophone as a third-year medical student. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Following service in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, Sullivan Jackson enrolled at West Virginia State University (WVSU), one of 107 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). He joined the WVSU Yellow Jacket collegiate band as a saxophonist in the mid- to late1940s, a time when marching band culture at HBCUs was evolving.

Collegiate marching bands originate from U.S. military bands that played music to boost soldiers' morale and keep tempo during long marches. Starting in the 1840s, American colleges founded marching bands on their campuses and in the 1890s, Tuskegee Institute — now Tuskegee University — became the first HBCU to have a band. At most colleges marching bands were a part of Reserve Officers' Training Corps programs during this time. For example, Tuskegee's marching band was a part of the school's military science department — not the music department — prior to 1931.

Tuskegee Institute Football Pennant, 1920-1950. / THF157606

World War I changed the type of music that bands played at HBCUs. Between 1917 and 1918, the U.S. Army mobilized 27 new Black regiments, all of which established regimental bands. The approximately 1,000 Black musicians mustered out for service in these bands included collegiate conductors and music professors from HBCUs. While standard military marches were a part of the regimental bands' repertoires, they also played popular music such as Missouri-style ragtime and New Orleans-style jazz. After the end of the war, the veterans returned to their jobs at HBCUs and conducted collegiate bands to play both march music and popular songs as they had during the war.

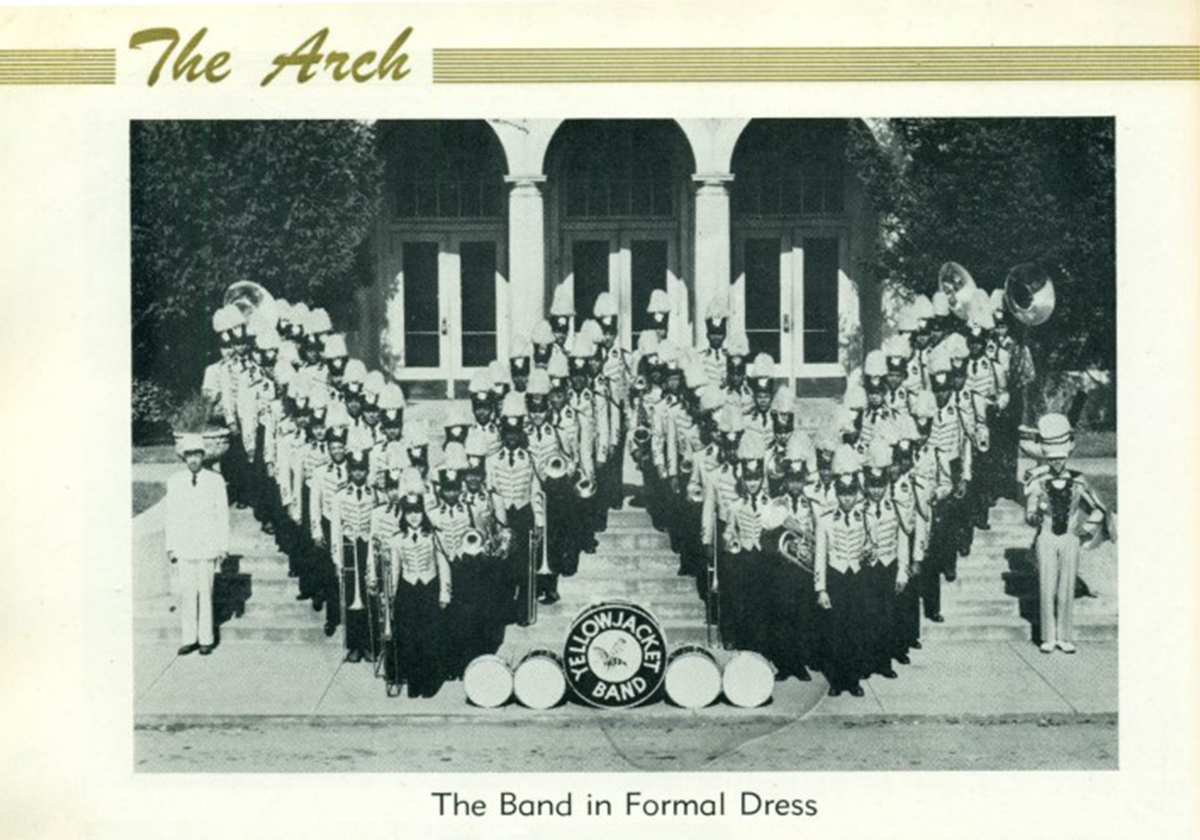

This evolution reached a crescendo in the mid-1940s while the future-Dr. Jackson was at WVSU. In 1946, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College — now Florida A&M University — hired William P. Foster to direct the school's marching band. Foster recruited returning GIs, professional musicians and high school students to play in FAMU's band. Foster's musicians performed solely popular music, building on the legacy of Black regimental bands during World War I. They also marched in elaborately choreographed and physically demanding routines that played well in newsreels and later on television. Over the following years, other HBCU bands adopted Foster'sflair for pageantry and emphasis on contemporary music and choreographed spectacles. Even Dr. Jackson's own West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket marching band posed in a W-shaped formation in the school's 1948-49 yearbook, demonstrating this cultural change at HBCUs. This legacy remains the gold standard of band performance at HBCUs today.

West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket Band, circa 1948. / Via West Virginia State University Drain-Jordan Library

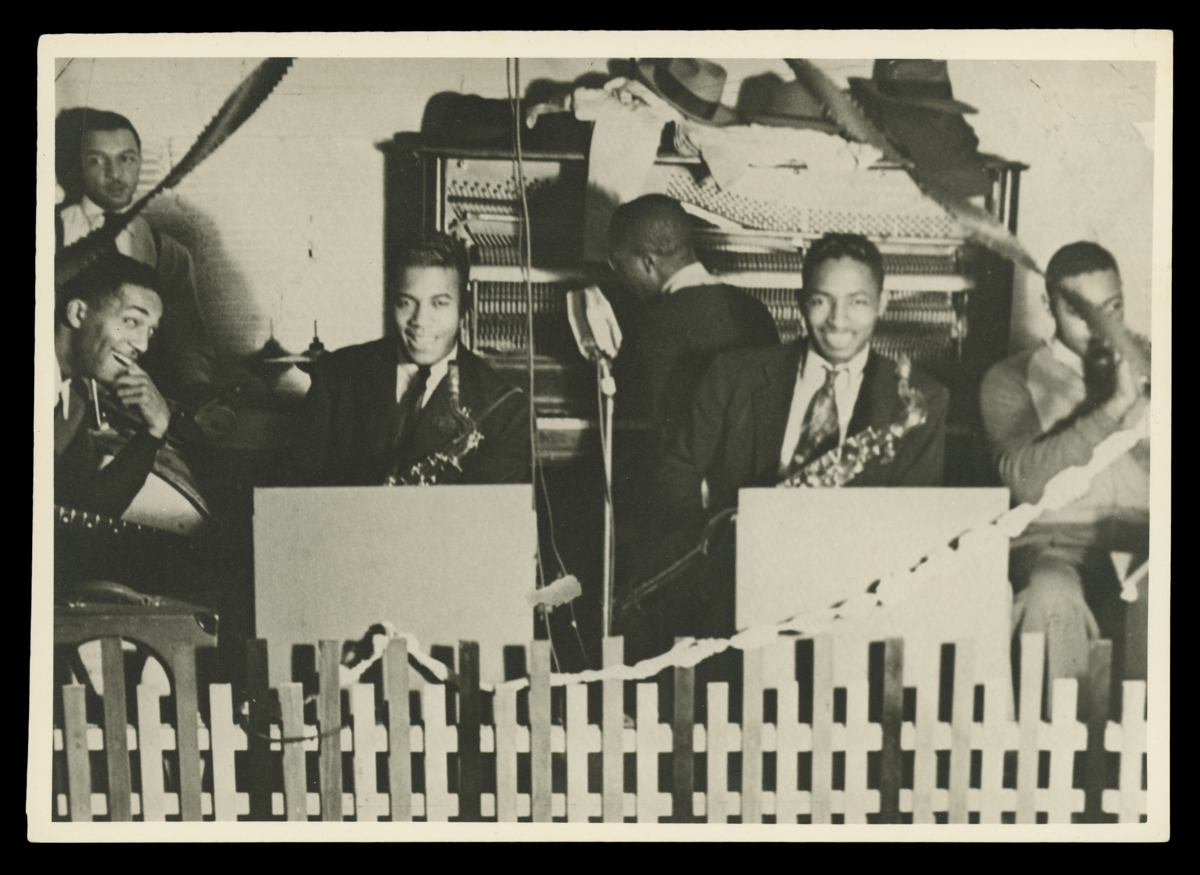

After graduating from WVSU, Sullivan Jackson pursued a degree in dentistry from Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. During that time, Dr. Jackson played saxophone in a band called the Doctors of Rhythm. The Doctors of Rhythm toured in what became known as the Chitlin' Circuit.

Sullivan Jackson with His Band, Date Unknown. Sullivan Jackson is seated second from the left holding his saxophone. / THF719998

Exclusionary segregation practices in the United States meant that traveling Black entertainers could not go to certain venues. In the 1920s, the only booking agency that served Black musicians, comedians, dancers or singers was the Theater Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.). However, performers who were booked through T.O.B.A. paid their travel expenses out of pocket and could only play at White-owned T.O.B.A.-affiliated venues.

When the Theater Owners Booking Association folded due to financial collapse in the 1930s, an informal network of Black booking agents and venues for Black clientele arose in its place. Performers now had the freedom to play where they liked: from large theaters like the Apollo in Harlem to the hole-in-wall juke joints in small towns like Hobson City, Alabama. This network was later called the "Chitlin' Circuit." The name is a riff on "Borscht Belt" venues that primarily booked Jewish American entertainers for Jewish American audiences; it is also a reference to chitterlings, a controversial staple of Southern American cooking.

The Orioles Music Group inside Fox Brothers Clothier, Chicago, Illinois, 1942. The Orioles were a pioneering rhythm and blues group that performed on the Chitlin' Circuit in the 1940s and 1950s. / THF184199

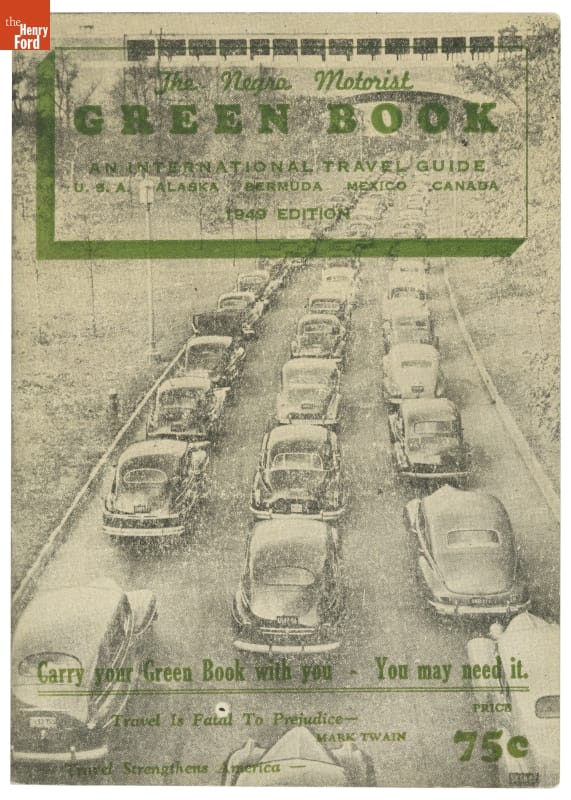

Performers like Sullivan Jackson appreciated the freedom afforded to them on the Chitlin' Circuit, but faced challenges on the road. Johnny Shines, a blues musician who toured the Circuit in the 1940s, described most venues as "rough" places where drinking, gambling, and fighting were common. Chitlin' Circuit audiences were notoriously harsh critics; the Apollo Theater emcee, "Sandman" Sims, used props like a hook or broom to kick acts off stage if the crowd booed them. Most venues paid the artists very little; sometimes payment came in the form of a hot meal instead of any money. Even traveling between shows could be perilous. Many Chitlin' Circuit performers had to drive all night to find safe lodging and were refused service while on the road. With Jim Crow laws in the South and thousands of sundown towns throughout the country, performers had to rely on resources such as the Negro Motorist Green Book and the hospitality from the communities they played in for travel, lodging, and food.

"Negro Motorist Green Book, An International Travel Guide," 1949. / THF77183

For a lucky few — like Chitlin' Circuit veterans Tina Turner, James Brown, Richard Pryor, or Jimi Hendrix — touring the Circuit was excellent training for their later famous careers. But even a short-lived entertainment career like Dr. Sullivan Jackson's provided Black performers with an opportunity to grow as artists and work within their own communities.

After graduating from Meharry Medical College, Dr. Sullivan Jackson became a dentist in Selma, Alabama, started his family and took part in the struggle for civil rights. But his connection to the music world was not severed. Among the Jackson family's many and frequent guests, traveling musicians — some of whom he played with — were also welcomed into the home. And Dr. Sullivan Jackson kept his tenor saxophone over the years and it is now part of the collection of The Henry Ford.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson's Selmer Mark VI Tenor Saxophone, 1968. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Facebook Comments