Farm-Made Cheese in a Big City Market

IMLS Agriculture & Environment Grant Work Continues

The Henry Ford received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to increase physical and digital access to agricultural and environmental artifacts. Staff from collections management, conservation, the photo studio, registrars and curatorial departments have worked with 1,200 items to date. Over the two-year grant period (September 2022 through August 2024), 1,750 objects will be conserved, cataloged, digitized and rehoused.

The IMLS grant has helped reunite several items donated by one farm family to The Henry Ford in 1973. These items were all used on a general farm owned and operated by William Saxony Rider (1857-1937) and his wife, Elizabeth Stephenson (1866-1948), in Almont, Michigan. Their daughter, Marion E. (1900-1974), remembered that her mother and father “made and marketed enough of this fine-tasting [cheddar] cheese to build a 300-acre farm.” That work likely occurred during the early 20th century, a time period described as the Golden Age of Agriculture, when market prices exceeded the cost of agricultural production and farm families prospered.

Continue ReadingFrom Work to Play: Industrial Locomotives and Park Trains

Opened in 1947, the Edaville Railroad quite literally transformed from an industrial railroad into an amusement attraction. / THF238726

Ellis D. Atwood only wanted to make his Massachusetts cranberry-farming operation more efficient. He’d purchased four steam locomotives and several railcars from narrow-gauge railroads in Maine, and he’d built 5.5 miles of track winding through his cranberry bogs. The trains hauled supplies into the bogs, and they carried harvested cranberries out of them. But then Atwood began offering rides at five cents a ticket.

Intentionally or not, Ellis Atwood discovered an entirely new business model for himself. Using his initials, EDA, for inspiration, Atwood named his operation the Edaville Railroad. Following his death in 1950, subsequent owners added rides and amusements and turned the operation into one of New England’s most popular destinations. The Edaville Railroad morphed from an industrial railroad into a “park train” – a railroad operated as part of a larger attraction.

Continue ReadingLegendary Dress: Iconic Histories of Drag Performance

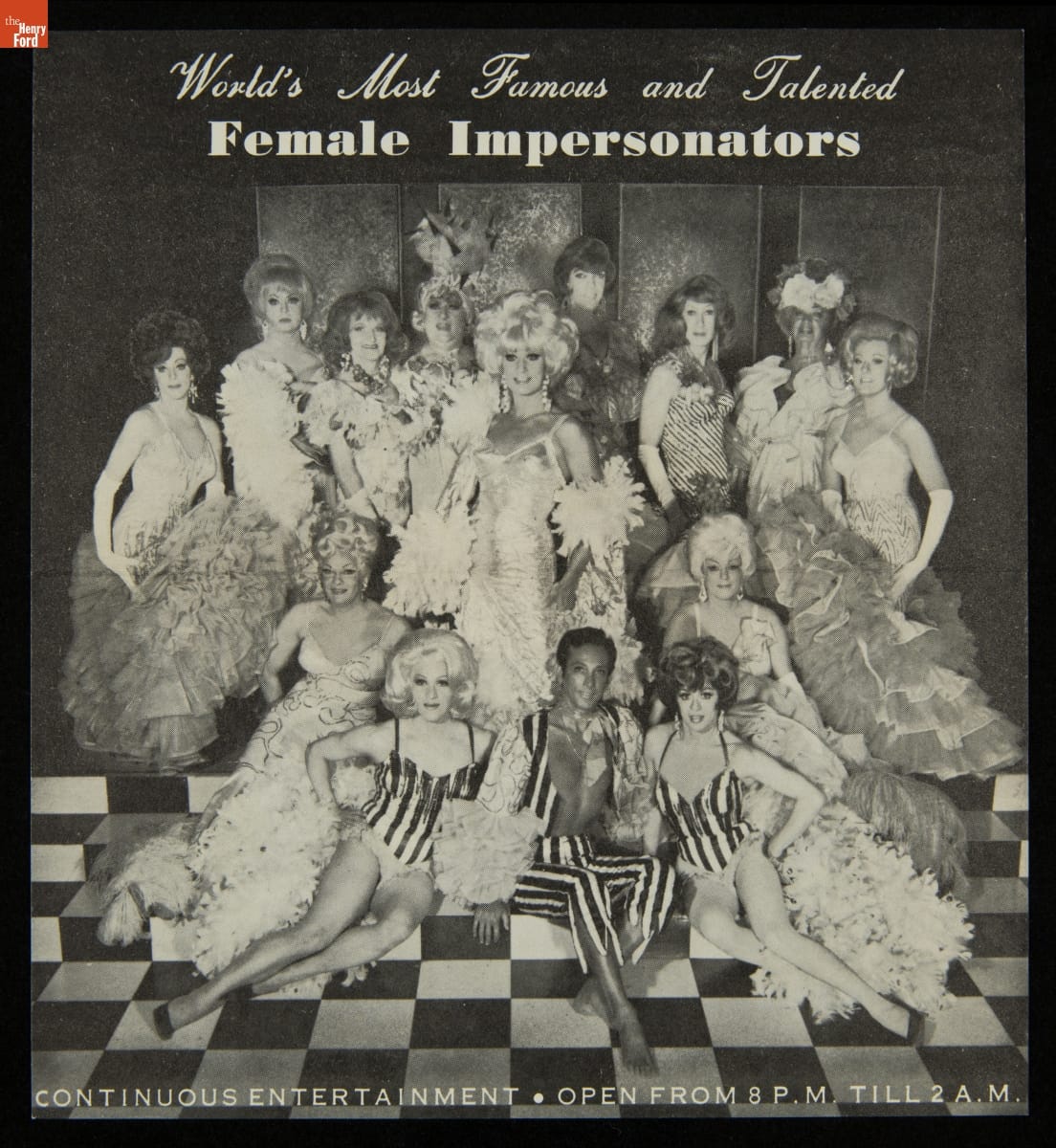

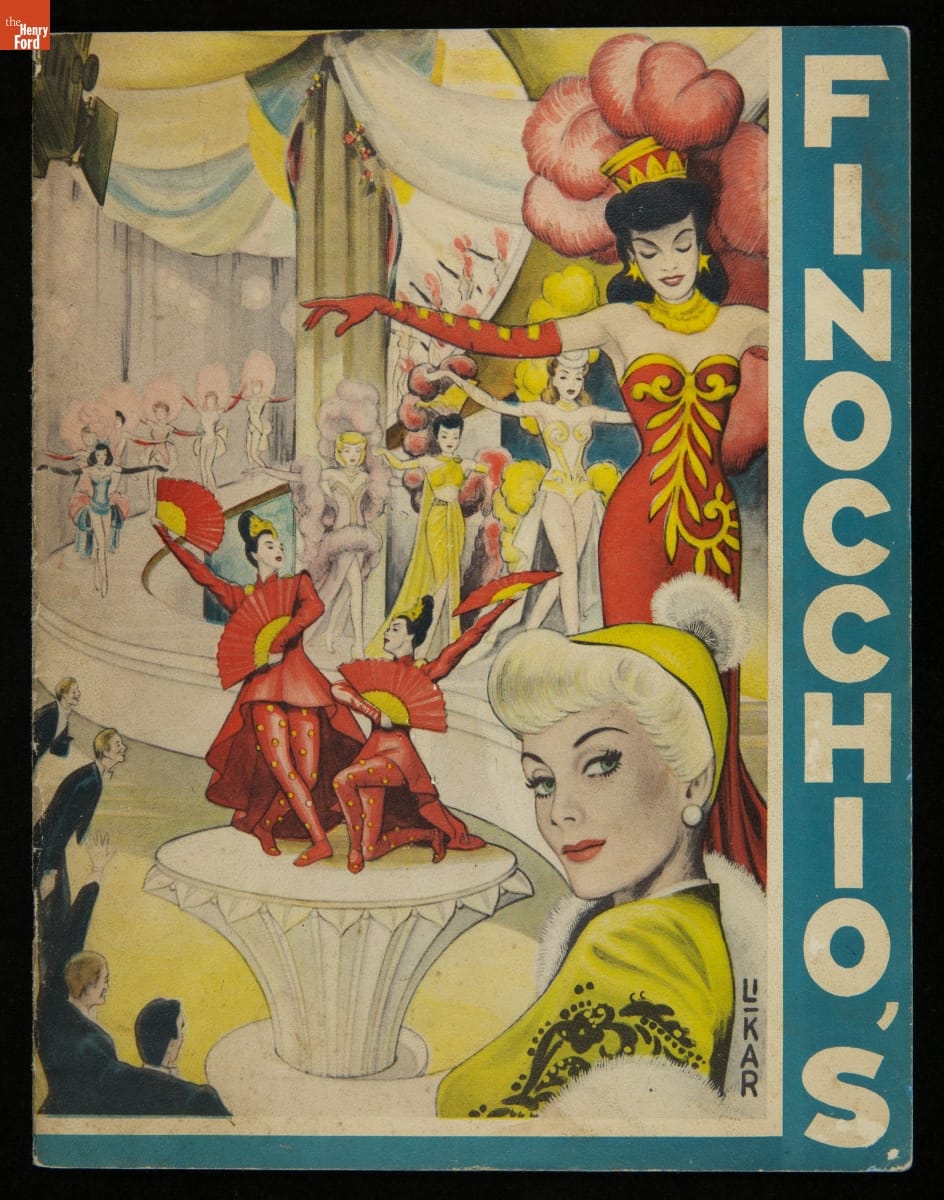

"Fabulous Finocchio's," 1960-1970 / THF708323

Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye lip-syncing “Sisters” in White Christmas…is drag.

Bugs Bunny dressed up as Lady Bunny to escape Elmer Fudd…is drag.

Robin Williams disguised as the nanny Mrs. Doubtfire…is drag.

Melissa McCarthy parodying Sean Spicer on Saturday Night Live…is drag.

Examples of drag performance in mainstream media are everywhere. For as long as society has reinforced ideas of gender norms, people have found humor and joy in playfully rejecting them.

Drag is a form of theater. Drag performers adopt personas and dress in over-the-top outfits to poke fun at the way society perceives masculinity and femininity. Drag holds a mirror to society. Although it has been a safe haven for the LGBTQ+ community, drag is for everyone.

In 2023, these topics were explored in a temporary exhibit, Legendary Dress: Iconic Histories of Drag Performance, in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Placed in historical lineage, the story of drag — and its performers — relates to the themes of identity and community that connect to The Henry Ford’s Social Transformation collections.

Images of Legendary Dress pop-up exhibit at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, September 2023.

Drag’s First Megastars: The Theater & Vaudeville

Wearing clothing assigned to a different gender has been common throughout history — especially on the stage. In ancient Greece, women were prohibited from acting, so men performed as female characters. Today, both men and women perform in roles that differ from their gender identity — to explore, for convenience and for comedy.

British playwright William Shakespeare famously explored gender fluidity in his plays through cross-dressing, notably in Twelfth Night and As You Like It.

Vaudeville was a genre of comedy entertainment popular from the 1880s into the early 1930s that was considered wholesome. “Impersonators” (actors or actresses dressed in drag) became celebrities for this craft. Impersonators did not always identify as queer, and their performances were not always meant to signal queerness to audiences.

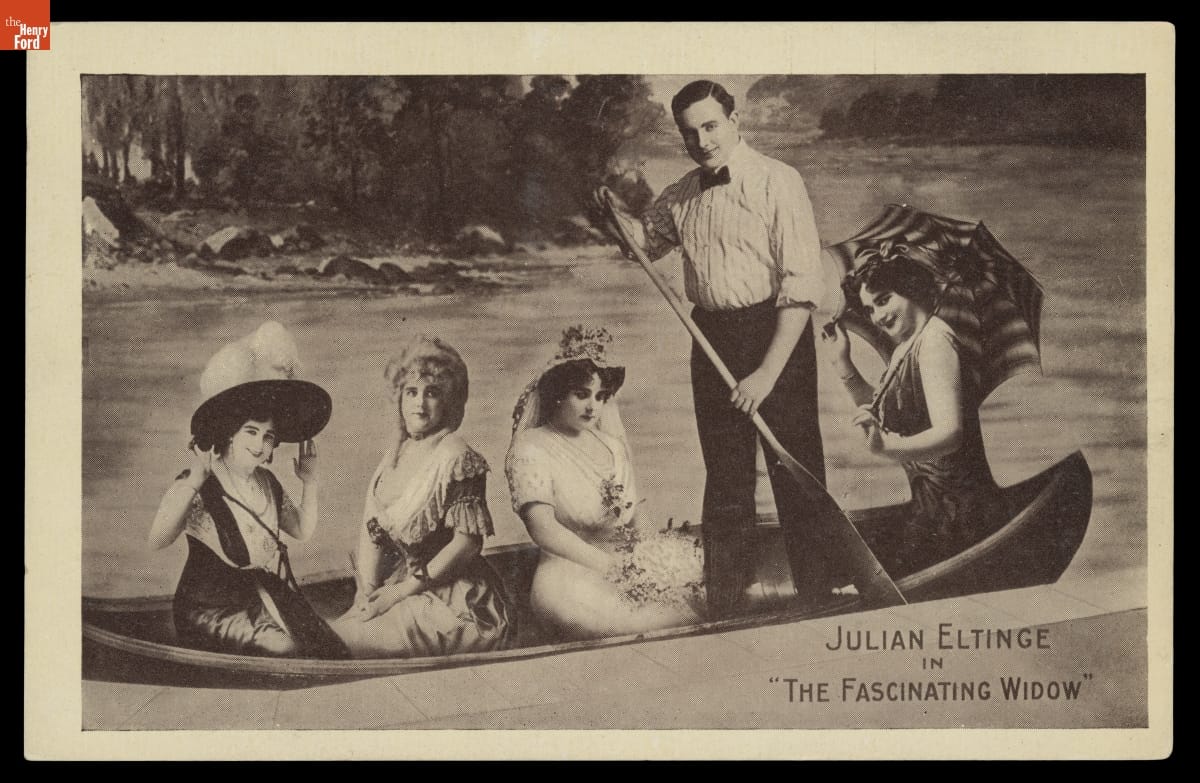

Julian Eltinge was the most famous and highly paid female impersonator of the early 20th century. He embodied gaudy elegance, wore glamourous gowns and perfected female mannerisms. The 1910 musical comedy The Fascinating Widow was his first play to open on Broadway. A promotional image shows a manly Eltinge rowing a boat with four other versions of himself in drag — each a character from the play.

Julian Eltinge in "The Fascinating Widow" at Forrest Theatre, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 1912 / THF712153

Misunderstood Histories of Drag: The Cooper Do-nuts Riot

When people are forced to exist on the margins — especially because of legal or safety concerns — the truth behind their lived experiences can become muddled. Sometimes, important histories are lost, which is why many people in LGBTQ+ and drag communities fight to keep their stories alive by becoming their own archivists.

The Cooper Do-nuts Riot represents an inaccurate LGBTQ+-focused history that has become widespread. However, we recognize that stories sometimes take on a life of their own — and even when they are wrong, they still have the capacity to teach.

One night in May 1959, a group of patrons — including two drag queens — gathered at a 24-hour doughnut shop in Los Angeles. When police officers entered the building to harass them, a clash began: Doughnuts and coffee cups were thrown; arrests were made.

In his novel City of Night, John Rechy gave this account, repeated as fact. But there is little evidence that the Cooper Do-nuts Riot happened in the way described: no news reports, police reports or photographs exist.

What is true is that Cooper Do-nuts was a safe haven for LGBTQ+ people in the 1960s and continues to be an inclusive space today. In June 2023, the site of the first Cooper Do-nuts shop was marked as a historic landmark. During the plaque unveiling, the LAPD apologized for their documented violence toward LGBTQ+ Angelenos in the 1950s and '60s.

Image of Legendary Dress pop-up exhibit at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, September 2023.

Performance as Safe Space

Drag finds its fullest expression in community. But what happens when drag becomes villainized, forced to go underground? As an artistic expression, drag has endured for centuries because it has adapted to changing social and political pressures.

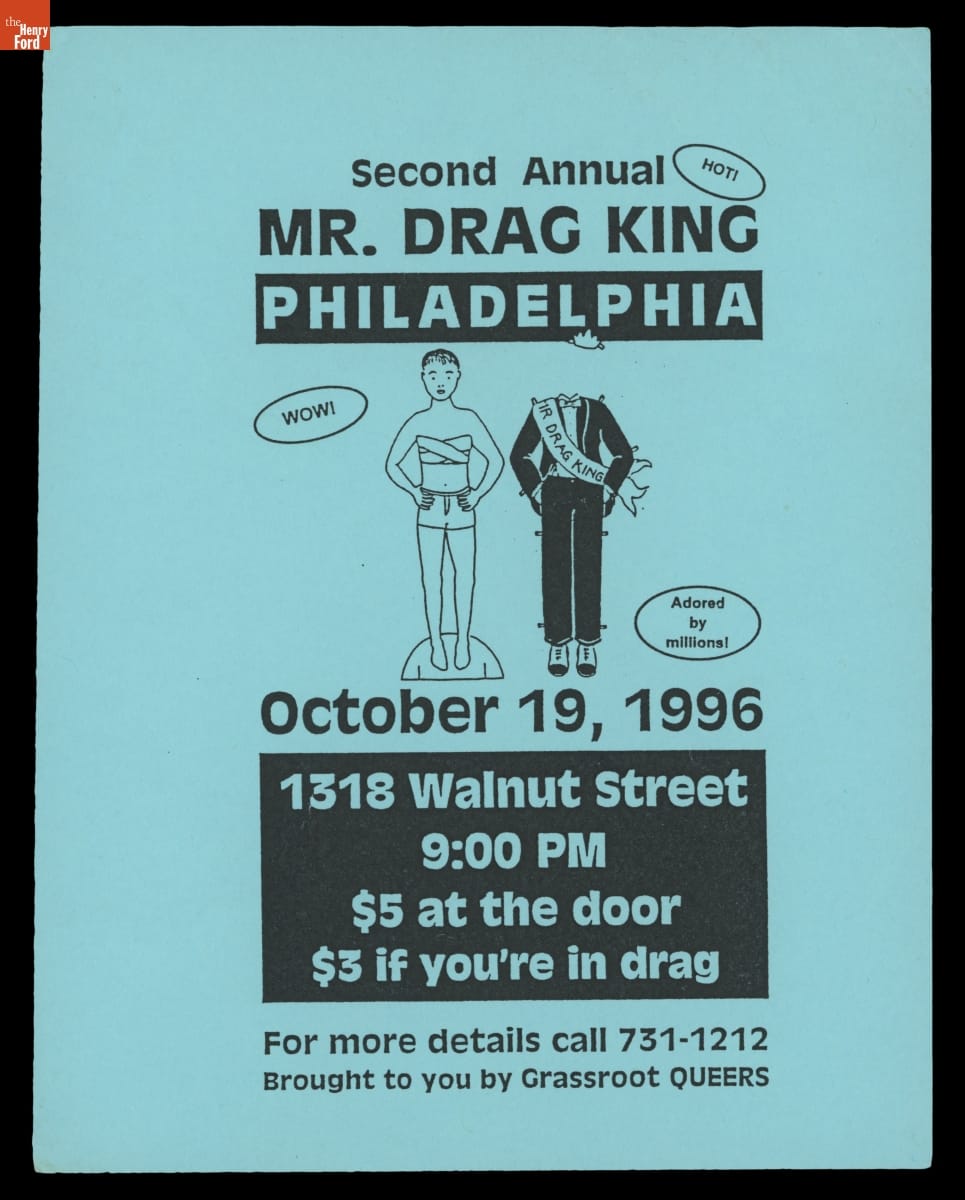

Drag king and queen competitions, coming-out parties and drag balls reigned supreme at nightclubs and queer spaces throughout the country in the second part of the 20th century. These events generally took place outside of the public sphere and became a safe space for the mostly LGBTQ+ community.

"Second Annual Mr. Drag King Philadelphia" Event Flier, October 19, 1996 / THF712087

An exception: Finocchio's nightclub opened in San Francisco and began featuring female impersonation shows just as the rest of the country turned away from them in the early 1930s. San Francisco’s laws against cross-dressing (in effect from 1863-1974) meant that the performers risked arrest if they stepped foot outside of the venue in drag. Finocchios closed in 1999 as the longest-running female impersonation show in the country.

"Finocchio's," 1960-1970 / THF708309

Recent Events: Sidetrack Bookshop

Sidetrack Bookshop is an independent bookstore located in downtown Royal Oak, Michigan. It is celebrated for its commitment to the LGBTQ+ community.

In March 2023, the store advertised a Drag Queen Storytime event for children and their families. Supporters of Drag Queen Story Hours see these events as education wrapped in entertainment — a place to promote inclusivity and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people from a young age.

A Michigan conservative group planned a protest, claiming the event was intended for “the grooming and sexualization of children.” The business held its ground, knowing that a demonstration would happen. Police provided crowd control for the 1,000 people that gathered outside of Sidetrack — the majority of whom were there to show support for the business and the rights of LGBTQ+ people of all ages.

Sidetrack Bookshop Drag Queen Storytime Event, March 11, 2023 / THF712149

Recent Events: Target & Pride

Target’s Drag Queen Bird figurine was launched as part of the company’s annual Pride-themed merchandise on May 1, 2023. After receiving viral attention on social media, a stock shortage caused this bird to become a collector’s item.

On May 24, 2023, Target issued a statement about its decision to move or remove Pride-themed merchandise in certain stores. The company cited safety concerns following backlash and vandalization by anti-LGBTQ+ activist groups.

Target’s decision received criticism from LGBTQ+ advocacy groups for what was perceived as a failure to stand with the community.

Pride Drag Queen Bird Figurine, 2023 / THF196639

Drag Queen Bingo

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, a Seattle nonprofit called Chicken Soup Brigade was founded to provide free meals and basic services to people living with AIDS. In the early 1990s, the organization held a fundraiser with the help of The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a group of drag queens from San Francisco that dressed as Catholic nuns. This Gay Bingo, or what would later be called Drag Queen Bingo, was a huge success — standing room only!

Bingo continues to be a popular drag performance platform. FIVE15 in Royal Oak, Michigan opened in 2007 and has introduced many people to drag through drag queen bingo events that offer what the venue calls “side-splitting hilarity and gender-bending fun” — a key feature of these events that today take place all over the country.

.png?sfvrsn=5dba3401_0)

Image of Legendary Dress pop-up exhibit at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, September 2023.

Kristen Gallerneaux, curator of communications & information technology at The Henry Ford, and Katherine White, curator of design at The Henry Ford, collaboratively produced this exhibit and blog.

Coffee, An Agricultural Commodity Revealed Through a New Project

A team at The Henry Ford is well underway on an exciting project funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). Staff from our conservation, photography, collections management, registrars and curatorial departments have been working together to process materials currently stored in the museum’s Collections Storage Building. We are focused on the Agriculture and the Environment Collection and related collections that can tell agricultural and environmental stories.

During this two-year grant project, we will conserve, catalog, digitize and rehouse an estimated 1,750 items. Here is a behind-the-scenes look at one of the many artifacts we've already processed that seem simple but reveal complicated agricultural histories. Recent work on a Turkish coffeepot provides a glimpse into the history of coffee as an agricultural commodity.

During the colonial era in America, British regulation over trade goods strained the relationship between colonists and British officials. You’ve likely heard much about tea, but coffee played a role in the resistance too. American ships became involved in the re-export of goods from Latin America through the new United States market, and therefore Americans acquired a taste for coffee as it arrived to them via countries like Brazil. Throughout the Revolutionary era, families ground coffee in their homes using coffee mills. Coffee consumption escalated in America thanks to re-exports in the new market. Once Americans realized the effects of caffeine, coffee became a staple for soldiers, travelers and families alike.

Coffeepot / THF193626

In the early 20th century, Americans enjoyed coffee more than ever. Turkish coffee in particular contains high levels of caffeine produced from a finely ground dark roast. It is made with boiling water in a cezve, a small pot with a long handle and lip for pouring. Consumers of the 1920s felt that Turkish coffee was thicker and more flavorful than the coffee of the past, and many Turkish coffeepots were produced during this era.

Coffeepot / THF193627

Continue Reading

Mail-Order Motoring: The Sears Motor Buggy

The 1909 Sears Model H Motor Buggy – basic, reliable transportation. / THF88309

Long before Amazon, American consumers counted on another company to deliver their wants and needs through the mail: Sears, Roebuck & Company. Founded in Chicago in 1892, Sears grew into the largest mail-order retailer — and, ultimately, the largest retailer, period — in the United States. Over the years, the company’s voluminous catalogs offered everything from clothing to appliances to farm equipment to houses. But even folks who remember those catalogs well might be surprised by another of its past products: automobiles.

Continue ReadingPicnics in Pictures

Graphic designer Steve Frykholm's picnic poster series for furniture company Herman Miller is inspired by classic outdoor eats, like sweet corn. The series represents some of the best known examples of American graphic design from the latter half of the 20th century. / THF188350

Watermelon, popsicles, barbecued chicken, hot dogs, sweet corn, lemonade and cherry pie. These are quintessential American picnic foods — sticky, drippy foods best eaten with your hands while sitting on a picnic blanket in the summer heat with friends or family by your side. These are symbolic foods, foods that hold memory. When graphic designer Steve Frykholm was tasked with creating a poster to announce his company’s employee picnic, he relied on these foods to communicate much more than a workplace memo ever could.

Continue ReadingFood, Fellowship and Fun

Attention-drawing antics and fun, friendly games have long been a part of the summer picnics attended annually by the thousands of members who make us the UAW's Local 600. / Photo Credit: Photo of UAW Field Day 1948 courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

When you’re observing the Dearborn Truck Plant’s final assembly line during the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, you’re watching a set of skilled operators put finishing touches on all-new Ford F-150s — one is built at the plant every 53 seconds. Those workers are part of UAW Local 600, a unit that’s some 5,000 members strong representing employees from the truck plant, its body shop and paint shop — an electric vehicle center has recently been added too — within the Ford Rouge Complex.

Continue ReadingEvocative Touchstone

Created more than 40 years ago, the period kitchens on display in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation remain a popular visitor draw, transporting observers to another place and time.

Hidden in plain sight in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation are four period kitchens — the last remaining element of a 1979 museum-wide exhibit upgrade timed to coincide with The Henry Ford’s 50th anniversary. Curators created these kitchen vignettes, representing the late 1700s to the 1930s, to help visitors explore changes through time, putting into context The Henry Ford’s rich collection of over 200 years of household equipment.

These kitchens have staying power. Nearly a half century later, the display continues to resonate with visitors. Not surprising, since kitchens are at the center of activity in a home. They conjure up feelings of security, familiarity, family and friends. Immersive environments like these period kitchens in the museum possess the ability to transport visitors to another place and time. They assist in imagining the lives of people of the past and help us ponder how those experiences relate to our own today.

Continue ReadingLasting Legacies

Metro Detroit is an area bursting with changemakers — those who break the mold to recreate it in their own image. Simply put: Forging your own path is the Detroit way. It’s also a sentiment actively celebrated within the physical spaces of The Henry Ford as well as instilled through its educational resources accessible online and around the world.

In the city’s culinary and grower worlds, several chefs and organizations are certainly blazing their own trails, working with a fierce passion and fortitude to create more equitable workspaces and, more importantly, more equitable food systems.

Whether it’s a woman-run kitchen where all voices are valued, a restaurant opened by immigrants who refused to fail or a BIPOC-led farm rooted in food sovereignty, thought leaders headquartered right in The Henry Ford’s backyard continue to set their own table when there isn’t a seat for them elsewhere.

Continue Reading

In June 1878, Eadweard Muybridge was hard at work. At the Palo Alto Stock Farm in Stanford, California, the photographer positioned 12 cameras along the side of a racetrack. A wire trailed away from each camera, connected to an electromagnetic circuit. Muybridge was meticulous; he wanted the experiment to work. Leland Stanford, once governor of California, commissioned Muybridge to answer a pressing question: When a horse ran, did all four hooves ever leave the ground?

It was a contentious topic among horse-racing enthusiasts, and Muybridge believed he could settle the matter using one of Stanford’s horses. Losing the horse onto the racetrack, as the animal careened around, it tripped the camera wires. Twelve tiny negatives were the result, capturing the full motion sequence. When Muybridge developed the images, they confirmed that when the horse gathered its legs beneath it, all four hooves left the ground.

Photographs from Muybridge’s series "The Horse in Motion." / Via Wikimedia Commons

Continue Reading