Playing Detective: Reading Clues from Local Landscapes

| Written by | Kristen Gallerneaux |

|---|---|

| Published | 3/28/2023 |

Beyond three-dimensional artifacts at The Henry Ford, there are intriguing narratives that can be divined from the very landscapes on which our campus sits — from Oakwood Boulevard to the Ford Rouge Factory Tour.

Playing Detective: Reading Clues from Local Landscapes

| Written by | Kristen Gallerneaux |

|---|---|

| Published | 3/28/2023 |

In the interview that follows, Kristen Gallerneaux, curator of communication and information technology speaks with curator of agriculture and the environment Debra Reid about some of the stories concerning past uses of these sites. Beyond three-dimensional artifacts at The Henry Ford, there are intriguing narratives that can be divined from the very landscapes on which our campus sits — from Oakwood Boulevard to the Ford Rouge Factory Tour.

Jim Johnson, director of Greenfield Village and curator of historic structures and landscapes, and Debra Reid, curator of agriculture and the environment, stand in the shadow of Greenfield Village’s oldest tree, an Eastern white oak that took root over 400 years ago. The two are committed to understanding more — and discovering things anew — about the land that The Henry Ford has called home for almost 100 years.

Kristen- As a 94-year-old institution, we have occupied this site for almost a century. But I’ve always been interested in finding ways to be more inclusive of stories about prior uses and past occupants too, especially knowing that the River Rouge oxbow flows through the back of Greenfield Village. This river was an important trade and industry route as well as an important resource for the Indigenous people who used this land before us. How do we “read” storied environments like these to understand them better today?

Debra- Downriver from our main campus, we have the Ford Rouge Factory Tour. That site is sometimes described as being an unused “wasteland” before it was developed for the original industrial complex. But there were Indigenous people living in the eluvial bottoms who were foraging in those rich areas — and later, French-owned ribbon farms, general and market garden farms.

In my research with French records and plat maps, there is strong evidence of complex history in the area surrounding what later became the Rouge plant. By 1915 and 1917, plat maps show who owned the land, and in Henry Ford’s correspondence, we can see how he systematically began to purchase land in this area. Eventually, 1,500 acres were identified for the Rouge plant’s site. You can extrapolate interesting histories from what happens along the Rouge River, and there is much more research needed.

Kristen- There have been so many fascinating stories connected to waterways in the metro Detroit area and across the border into Canada. But the presence of Indigenous people that preceded and coexisted in this area, alongside the founding of Detroit, has often been washed away by the dominating spotlight of industrial histories.

Debra- And also “washed away” in the sense that when industrialists acquire 1,500 acres on a river, what disappears because of that? There were also ancient mounds and sand dunes near Zug Island, which were taken down by a glass factory across the river in Delray. The sands from mounds became the raw product for the glass plant. [Editor’s note: Zug Island sits at the confluence of the Detroit River and the mouth of the Rouge River. Before European arrival, it was an ancient burial ground but was heavily industrialized in the 1890s.] Their archeological remains were disseminated.

So, if we think of industrial destruction of evidence of Indigenous presence as a typical approach for the time and we head back upriver to the Rouge plant, what, if anything, remained of an archeological record when construction began there? Images show how soil was removed down to the bedrock to put in pilings, which obliterated the archaeological evidence. But even before Ford, in 1889, the Detroit International Exposition & Fair was held not far from this site, which I discovered while researching the Detroit Central Market. There is an article that shows our market building, and it also mentions leveling mounds in preparation for the fair.

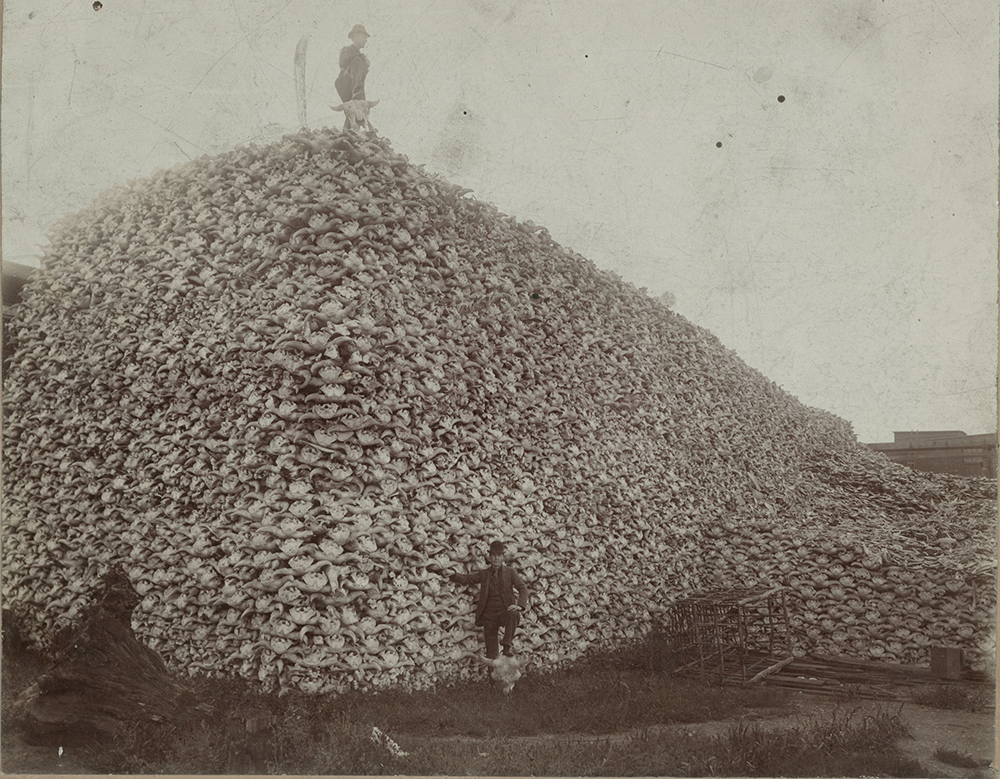

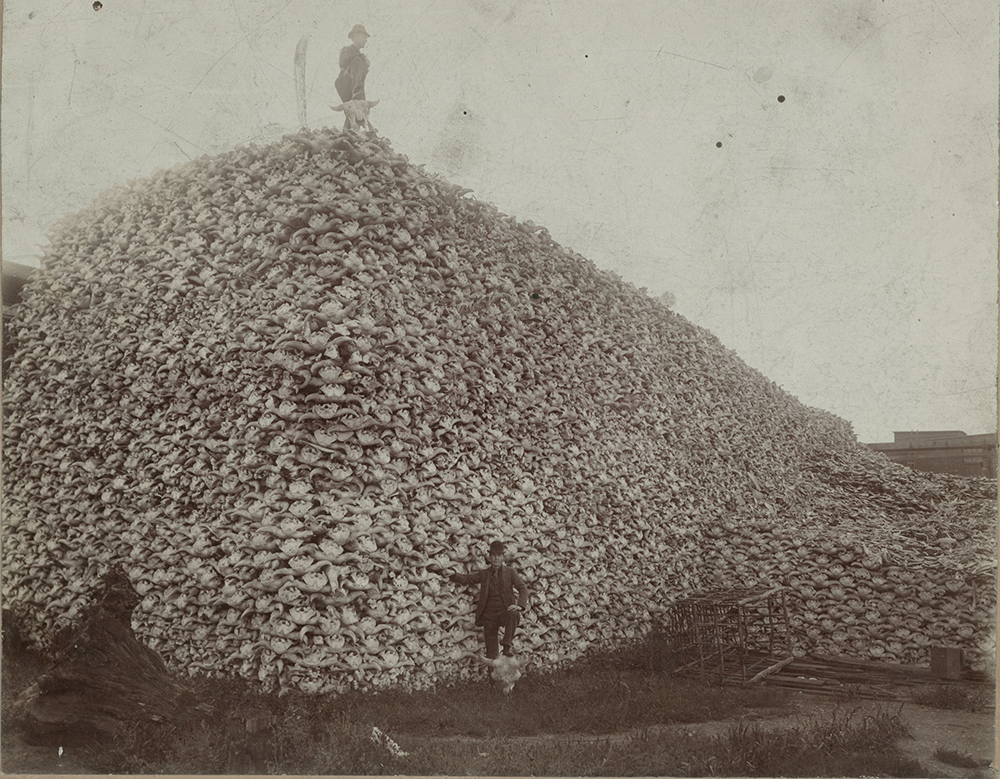

On streets not far from The Henry Ford’s campus, enormous piles of buffalo bones once sat in the late 19th century, waiting to be rendered down for use in a wide range of consumer products. / From The Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Kristen- I know of a street in Delray called Carbon Street and once found an incredible image from the late 19th century of men standing on that street on top of enormous piles of buffalo bones that were going to be rendered down for things like pigments. Once you see these images, it’s hard to forget them.

Debra- Yes! And those bones were charred — basically obliterated — and found their way into a wide range of consumer products. The buffalo were annihilated on the U.S. Plains after European arrival, and the bones of bison were shipped to places like Detroit. This was a huge stove-making city, and the blacking made from the bones was used to keep stoves black. Pharmaceutical industries also used the bones, and they were processed into bone meal fertilizer and other agricultural byproducts. So the material rendered from the bones in that image impacts farming, consumerism, medicine...

Kristen- ...it was even used as pigment in “bone black” printing ink. Which means that people were literally receiving information and viewing printed images by “reading” buffalo byproducts. The onion layers of history keep opening. It can get quite overwhelming if you think about it too much.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter-Spring 2023 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Jim Johnson, director of Greenfield Village and curator of historic structures and landscapes, and Debra Reid, curator of agriculture and the environment, stand in the shadow of Greenfield Village’s oldest tree, an Eastern white oak that took root over 400 years ago. The two are committed to understanding more — and discovering things anew — about the land that The Henry Ford has called home for almost 100 years.

Kristen- As a 94-year-old institution, we have occupied this site for almost a century. But I’ve always been interested in finding ways to be more inclusive of stories about prior uses and past occupants too, especially knowing that the River Rouge oxbow flows through the back of Greenfield Village. This river was an important trade and industry route as well as an important resource for the Indigenous people who used this land before us. How do we “read” storied environments like these to understand them better today?

Debra- Downriver from our main campus, we have the Ford Rouge Factory Tour. That site is sometimes described as being an unused “wasteland” before it was developed for the original industrial complex. But there were Indigenous people living in the eluvial bottoms who were foraging in those rich areas — and later, French-owned ribbon farms, general and market garden farms.

In my research with French records and plat maps, there is strong evidence of complex history in the area surrounding what later became the Rouge plant. By 1915 and 1917, plat maps show who owned the land, and in Henry Ford’s correspondence, we can see how he systematically began to purchase land in this area. Eventually, 1,500 acres were identified for the Rouge plant’s site. You can extrapolate interesting histories from what happens along the Rouge River, and there is much more research needed.

Kristen- There have been so many fascinating stories connected to waterways in the metro Detroit area and across the border into Canada. But the presence of Indigenous people that preceded and coexisted in this area, alongside the founding of Detroit, has often been washed away by the dominating spotlight of industrial histories.

Debra- And also “washed away” in the sense that when industrialists acquire 1,500 acres on a river, what disappears because of that? There were also ancient mounds and sand dunes near Zug Island, which were taken down by a glass factory across the river in Delray. The sands from mounds became the raw product for the glass plant. [Editor’s note: Zug Island sits at the confluence of the Detroit River and the mouth of the Rouge River. Before European arrival, it was an ancient burial ground but was heavily industrialized in the 1890s.] Their archeological remains were disseminated.

So, if we think of industrial destruction of evidence of Indigenous presence as a typical approach for the time and we head back upriver to the Rouge plant, what, if anything, remained of an archeological record when construction began there? Images show how soil was removed down to the bedrock to put in pilings, which obliterated the archaeological evidence. But even before Ford, in 1889, the Detroit International Exposition & Fair was held not far from this site, which I discovered while researching the Detroit Central Market. There is an article that shows our market building, and it also mentions leveling mounds in preparation for the fair.

On streets not far from The Henry Ford’s campus, enormous piles of buffalo bones once sat in the late 19th century, waiting to be rendered down for use in a wide range of consumer products. / From The Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Kristen- I know of a street in Delray called Carbon Street and once found an incredible image from the late 19th century of men standing on that street on top of enormous piles of buffalo bones that were going to be rendered down for things like pigments. Once you see these images, it’s hard to forget them.

Debra- Yes! And those bones were charred — basically obliterated — and found their way into a wide range of consumer products. The buffalo were annihilated on the U.S. Plains after European arrival, and the bones of bison were shipped to places like Detroit. This was a huge stove-making city, and the blacking made from the bones was used to keep stoves black. Pharmaceutical industries also used the bones, and they were processed into bone meal fertilizer and other agricultural byproducts. So the material rendered from the bones in that image impacts farming, consumerism, medicine...

Kristen- ...it was even used as pigment in “bone black” printing ink. Which means that people were literally receiving information and viewing printed images by “reading” buffalo byproducts. The onion layers of history keep opening. It can get quite overwhelming if you think about it too much.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter-Spring 2023 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Themes |

|---|