Posts Tagged by regina parsell

Victorian Hairwork Albums

At The Henry Ford, we often think of the countless stories of innovation that our institution can tell through archival materials—from the automotive parts drawings to the Bill Stumpf and Robert Propst design collections. Beyond these examples, there are many stories of American life in the last few centuries. Materials collected over the years document different aspects of life, both public and private, and tell stories of how society has survived, as life changed rapidly. We turn to museums and archives to tell “the big stories” of the past. But what about the small ones, the ones that go unnoticed? These hidden gems are often what tell us the most about what life was like, because they highlight what was most precious to the average person.

Two hair albums in the Collections of The Henry Ford, Acc. 56.40.1 (top) and 38.509.1 (bottom) / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Two hair albums in the Collections of The Henry Ford, Acc. 56.40.1 (top) and 38.509.1 (bottom) / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

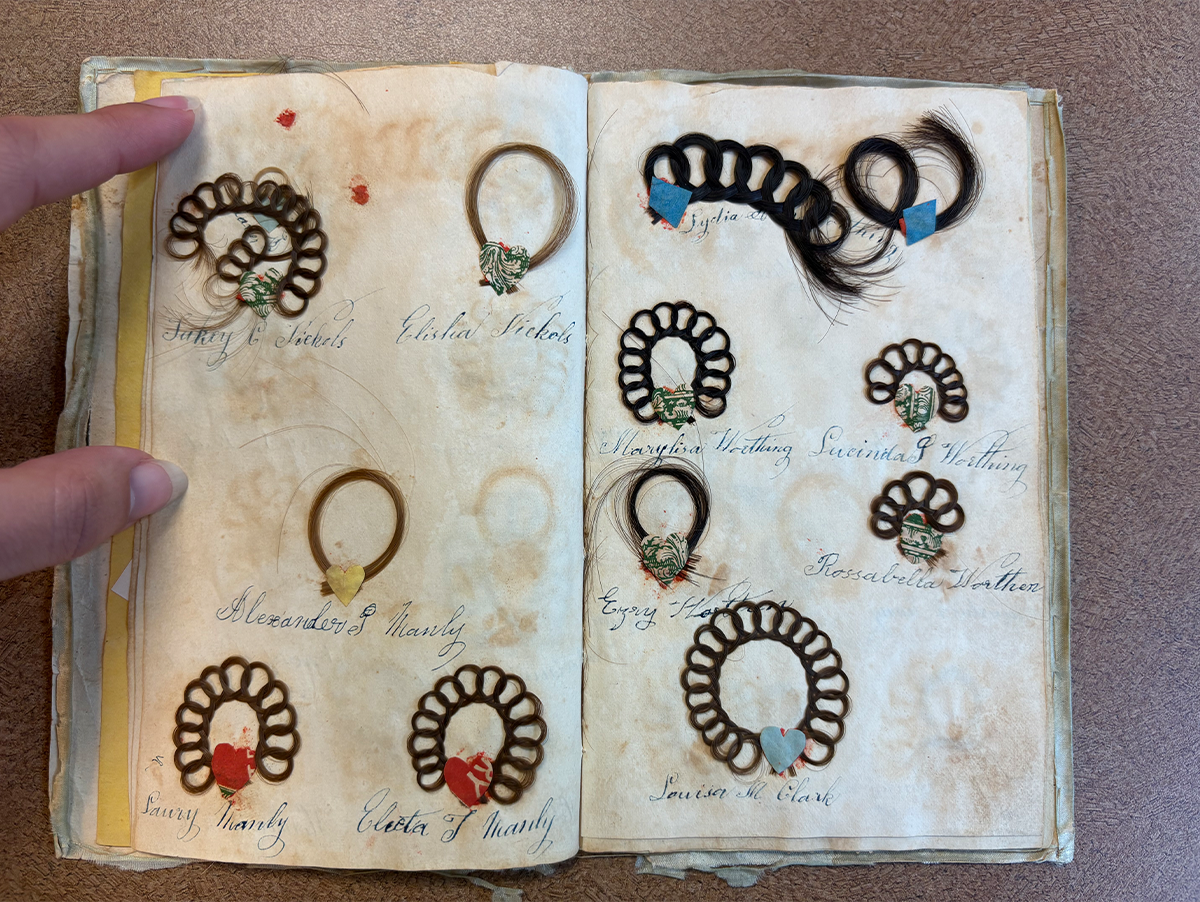

Finding these hidden gems in an archive is not as uncommon as you would think, especially when you have a collection the size of The Henry Ford’s. When I first started as a processing archivist, I decided to look through some of our unprocessed boxes to get a better idea of what items were in our holdings. This is how I found a folder labeled “hair albums,” containing two albums (as seen above) from 1850 and 1858, belonging to Sarah Smith and Chloe Thayer, respectively. At the time, I didn’t know what treasures I was holding, but through meticulous research and curiosity, I have unearthed powerful stories connected to everyday life in the mid nineteenth century.

What is a hair album? Sometimes called autograph albums or friendship albums, hair albums contain locks of hair along with verses from friends and family. They come from the Victorian era, largely in the time span of 1850 into the early 1900s. This era is notably remembered for its mourning practices. Many will be familiar with hair wreaths and hairwork jewelry that was created as a way of memorializing the dead. Hair albums, however, were created with the purpose of showcasing friendships and the ties that bind people together, not just to memorialize a life. For example, hair albums were sometimes made as farewell presents for women who were getting married and moving away. At a time when photographs were not common in use or availability, giving a lock of one’s hair was a very real representation of giving a piece of oneself to be remembered by. As author Neely Tucker wrote in an essay on this topic, “People might go months or years between seeing one another; a lock of hair was a meaningful talisman.”

Opening page of Smith Album, Accession 38.509.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Opening page of Smith Album, Accession 38.509.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

After I discovered what a hair album is, and why they were made, I started looking for examples held in other institutional collections to compare notes. I wanted to find out how they described these albums, which then informed me how to describe the Smith and Thayer albums at The Henry Ford. The Newberry Library has a lovely hair album from 1845 available in their digital collections, which is similar in look to the Thayer Album. Harvard and Pennsylvania State universities also have hair albums in their collections. I reached out to Penn State to see if their processing archivist who worked on their albums would be willing to answer questions I had about their process, but unfortunately that person had long since retired. My next idea was to contact an expert on hair albums and ask them what they look for in a successful archival finding aid, which is used by researchers to find materials they want to review.

This led me to Dr. Helen Sheumaker, a professor at the University of Miami in Miami, Ohio, and author of Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America. Dr. Sheumaker's book was one of the first sources I found that discussed hairwork outside of the context of the history of mourning, and after I read through it, I felt that she would be a good resource for me on this project. She graciously agreed to a virtual meeting, where we could review the hair albums in the collections of The Henry Ford, and to help me come up with descriptive terms for them.

Pages from Thayer Album, Accession 56.40.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Pages from Thayer Album, Accession 56.40.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

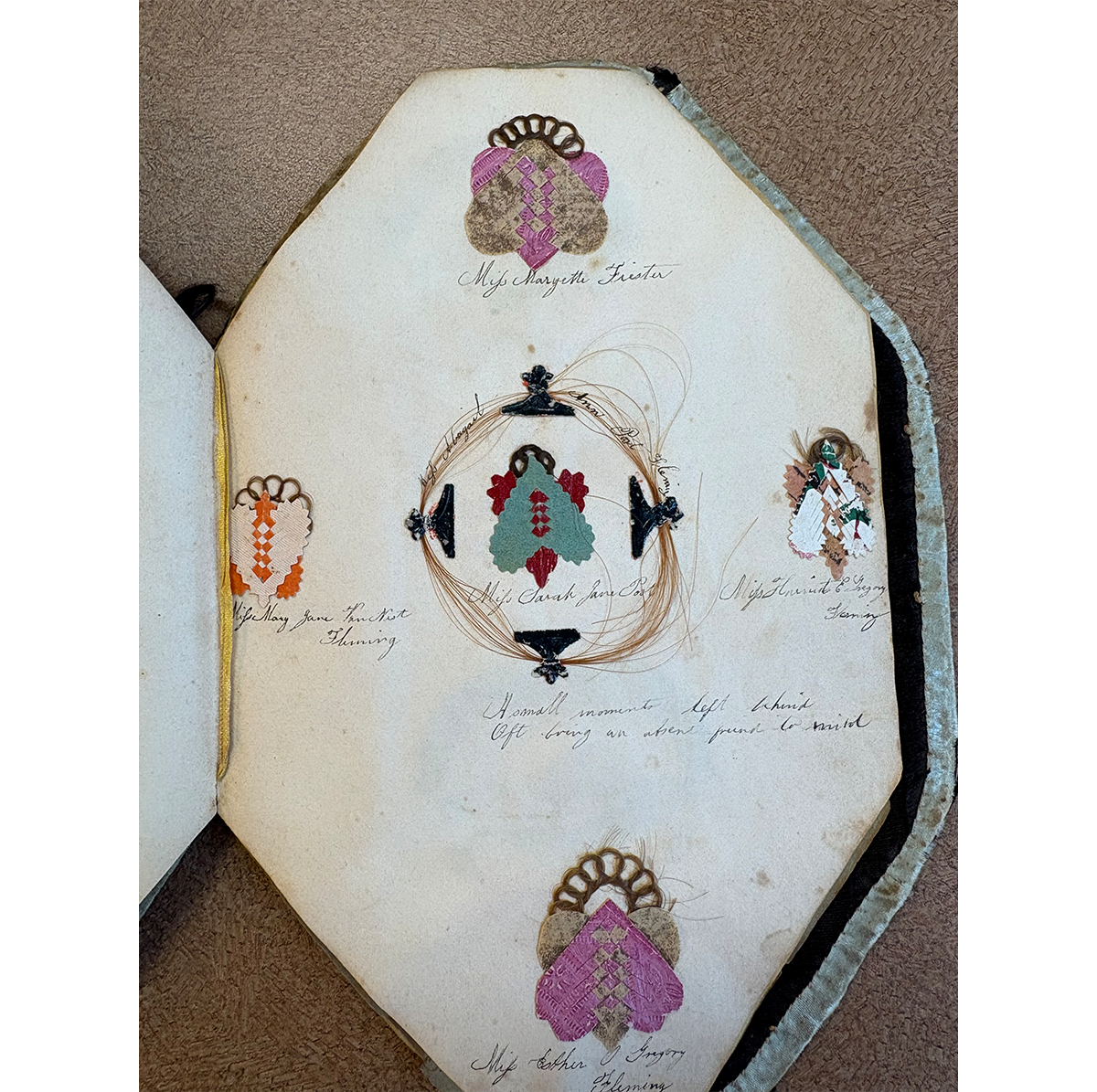

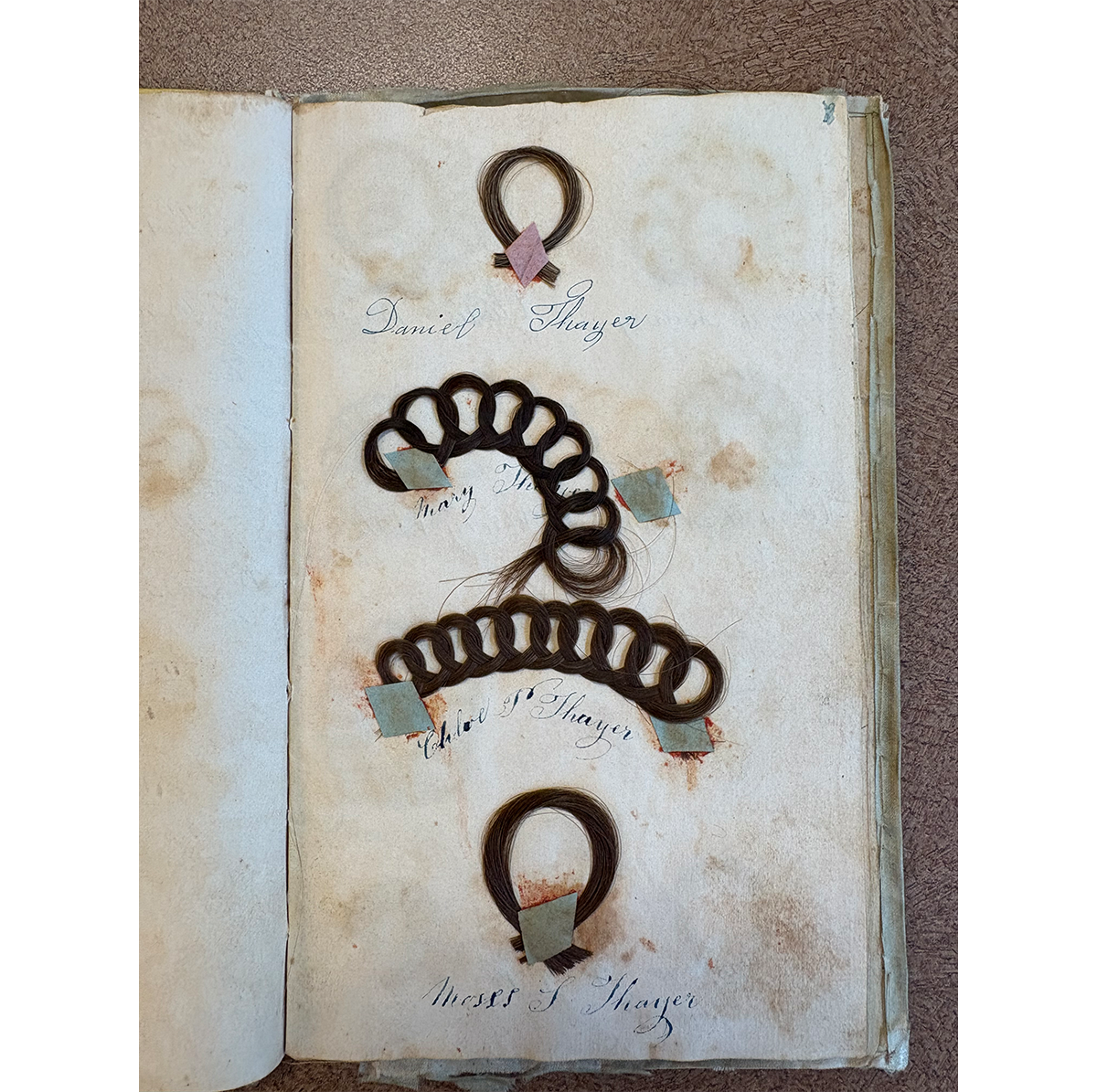

While each album is unique, they have similarities. For example, locks of hair are arranged in familial groups, with persons of the same last name presented together. Both books are handmade and likely made with repurposed materials like wallpaper or dress fabric. The Smith Album in particular shows signs of hand stitching along the edge of the cover. The handwriting throughout the books is consistent, giving the impression that the creator collected the materials and assembled the book later. But what is different?

Pages depicting different colored woven hearts in Smith Album, Accession 38.509.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Pages depicting different colored woven hearts in Smith Album, Accession 38.509.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

The Smith Album is more ornate of the two, which can be seen from the intricacy and detail present on each page and the elongated octagon shape of the album. When comparing the hair looping and braiding between the two albums, the Smith Album shows precision to detail, while the Thayer Album contains more loose hairs. The woven hearts holding the hair in place in the Smith Album vary by page and appear to be collected from the donor. This is not the case with the Thayer Album, with blue and pink paper being used throughout.

Pages from Thayer Album showing simple hair loops, Accession 56.40.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Pages from Thayer Album showing simple hair loops, Accession 56.40.1 / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

These differences may be due to the ages of the two women creating the albums, as it is likely that the Smith Album was created as a going away present for Sarah Smith's wedding while Chloe Thayer was a young schoolgirl. Understanding these foundational differences provides the context necessary to accurately describe these materials. Talking with Dr. Sheumaker, I was able to grow my knowledge of hair albums, and also determine a strong vocabulary needed to make them rise to the surface for future researchers. While not every archival processing story involves this level of research, most do involve a level of curiosity and a passion for discovery. Understanding the details is crucial, especially in the moments when you find yourself describing the little stories—like friendship—to make materials like these viewable within our collections.

Regina Parsell is a Processing Archivist at The Henry Ford.