Posts Tagged the henry ford magazine

The Alchemy of Empathy

Experiential opportunities in cultural spaces can nourish emotional connections

By Elif M. Gokcigdem, Ph.D.

To challenge behaviors that contribute to fragmentation in our communities, we need more than an intellectual understanding of our interconnectedness. Besides knowledge, we need a deeper connection that makes us care and act compassionately toward the whole to which we belong — all of humanity, our kin that we share our world with and our planet.

We perceive and experience this indivisible whole from our respective worldview, which is shaped by the narratives we grow up with, our physiology, culture, language and other factors. The way we view the world influences how we make meaning of ourselves as well as what we share our existence with — people, objects, ideas, nature. What we find meaningful and worthy of our love, in turn, influences our behavior and actions, shaping how we live.

Empathy, our inherent ability to perceive and imagine what it might feel like to be the other, challenges our habitual worldview. When we feel an emotional connection to others’ experiences, our worldview expands to include diverse narratives. Experiencing this capaciousness lets us develop a broader sense of self who is able to witness their own attitudes, choices and behavior within the wider context of a collective existence. Witnessing and articulating our unique perception empowers us with agency to notice our motivations and calibrate our actions.

As we face increasingly complex global challenges, it is essential to reflect upon what empathy means to the collective of which we all are an integral part. Cultural spaces — like museums — are critical resources for empathy-building. Informal learning platforms, they can expand our worldview, allow us to explore narratives different from our own and perceive ourselves and our actions not as separate and singular, but integral to the whole.

During the last decade, I have been immersed in a multifaceted exploration of empathy-building through museums, leading a multidisciplinary and international community to deepen our understanding of this ability to relate to others and their experiences, and how to innovate new tools that can position museums as incubators for further empathy-building.

As I observed how intentionality and collaboration across cultures, disciplines and sectors were essential to this effort, the Designing for Empathy® framework and ONE - Organization of Networks for Empathy were born. Designing for Empathy® is an evolving framework that considers a oneness mindset as a master perspective, inspiring how we might see the world around us and our place in it, while reminding us to calibrate and harmonize our attitudes and behavior toward the collective. Within this context, empathy-building is defined as an intentionally designed, transformative lived experience through an encounter with the other that leads to an understanding of the self — not merely as a dispensable part, but as essential to the whole.

Museums allow us to intentionally utilize them as readily available platforms for transformative experiences of empathy and contemplation, where each encounter can be an opportunity to develop a knowledge of our humanness and the filters through which we perceive the world. While empathy-building requires intentionality, it also demands the presence of conducive ingredients within the “alchemy of empathy: storytelling, experiences of awe and wonder, dialogue, experiential learning and contemplation. Each of these ingredients (which are further explained on the following pages) offers a portal into a deeper knowing due to the transformative qualities they are rooted in — curiosity, vulnerability, authenticity, sincerity, humility, courage and trust.

Ingredient: Storytelling

Through first-person accounts, powerful stories from the point of view of the cultures featured, authentic objects and factual information, museums can offer opportunities to bear witness and articulate past and current events, and imagine what it would feel like to be a part of another’s lived experience.

Example: Greensboro Woolworth Lunch Counter

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., invites visitors to immerse themselves in the powerful narratives of the segregated Greensboro Woolworth Lunch Counter interactive exhibition. As visitors take a seat at a modern interpretation of the 1960s diner, they can choose to learn about the Selma March, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Woolworth’s Sit-in. Surrounded by dynamic visual storytelling elements and authentic artifacts, participants are then presented with choices that test their willpower in the face of adversity as they are asked to think about how they would respond if faced with these situations.

Ingredient: Awe & Wonder

An extraordinary experience, something that is otherwise inaccessible in our daily lives, or the immediacy of a newly found perspective on something ordinary, can shift our entrenched perspectives and paradigms, allowing us to explore our capacity for expansion and transformation through vulnerability and contemplation.

Example: Unsupervised

New York MoMA’s historic acquisition of Refik Anadol’s AI-powered installation Unsupervised offers a captivating experience that challenges our sense of place, time and scale. It invites us to find solace within by immersing ourselves in something vast, generative and fluid in its simultaneous and ever-changing creative expression.

Ingredient: Dialogue

Learning to hold off judgment is essential to any meaningful dialogue. Cultural resources in museums can provide a wide spectrum of context, bringing people together for facilitated experiences of non-judgmental listening and dialogue. Proximity to another’s narration of a lived experience, combined with intentionality and undivided attention, create space for empathy and trust to flourish.

Example: A Collective Dialogue: Exploring Belonging through Art & Empathy

At this public workshop I facilitated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., we explored the themes of “othering and belonging,” utilizing Robert Motherwell’s massive Reconciliation Elegy as the context for an engaging collective dialogue using the Creative Tensions method. Within this method, movement is often used in situations that require perspective, creativity and idea generation. A facilitator presents participants with prompts and invites them to express their stance on the matter by moving to one side or the other of a predetermined area. As individuals are invited to explain their choices, others are free to change their positions by getting closer or farther away from what is being shared.

Ingredient: Experiential Learning

An encounter is required to create, track and unfoldan inner experience such as empathy or a perspective shift, where one can witness the self, the other and the greater context within which the experience is unfolding. Through experiencing, witnessing and articulation, one might develop the agency to take responsibility of habitual perspectives and biases at the point of their arising.

Example: Human Phenomena

San Francisco’s public learning lab, the Exploratorium, includes the Osher Gallery which focuses on Human Phenomena. Here, a variety of playful, yet thought-provoking experiences enable visitors to explore some of the world’s most pressing problems through the lens of human perception, behavior and social interactions.

At the Science of Sharing exhibit set, for example, visitors are presented with situations inviting an immediate response in the form of a choice expressed by a real-time, real-life action. This human experience of encountering a moment of choice then becomes the subject and the object of the experience, opening up possibilities for developing a knowledge of the self through articulation and contemplation.

Ingredient: Contemplation

Expanding our circle of empathy requires conscious awareness, meaning-making and reflection. Contemplation allows us to go beyond our first impression of what is apparent into a search for its meaning and essence. What we find meaningful, or meaningless, shapes who we become as it influences our behavior. Through contemplation, each encounter with the other becomes an opportunity to discover something new about the self, and ultimately to transcend the self within a wider context.

Example: Mandala Lab

New York’s Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art’s Mandala Lab is a traveling experience that centers on an ancient Tibetan mandala to invite deep reflection on the human condition. As participants witness their unique perception and behavior through a series of encounters, they also observe a wide variety of reactions expressed by others around them, inviting contemplation on individual perspectives and actions within the expanded context of our shared humanity.

Editor’s note: The Rubin Museum transitioned to a decentralized, global museum model in fall 2024, closing its 17th Street building in New York City. Today, the museum serves people across the world through traveling exhibitions and experiences, along with partnerships, collection sharing, resources for artists and scholars engaging with Himalayan art, and digital content.

——

Time for Self Reflection

A look at what The Henry Ford is doing to build empathy on its campus, through the lens of those doing the work

The Henry Ford Magazine asked a small collective of The Henry Ford’s team to reflect on the role museums can play in empathy-building and what they experience, contemplate and hope to accomplish on our very own campus to encourage visitors to explore their own sense of self and interconnectedness to others. Experts from varied disciplines were chosen to give readers multiple perspectives, from longtime curators and our leadership responsible for talent development and community engagement to our most analytical minds and new faces giving fresh takes on theatrical programming. For scope, we asked everyone to consider the same questions. Here are the questions and their responses.

Why is it vital for educational/entertainment venues such as a museum to build empathy into their “culture” — from their guest experiences and programming to their collections and physical spaces.

From your perspective, what is The Henry Ford doing right in terms of its empathetic interventions? Can you share your hopes for the future?

Empathy Through Insight

Jarell Brown

Director of Analytics & Business Intelligence (B.I.R.A),

Principal Innovator of Innovation Atlas

The Henry Ford

Building empathy into the culture of educational and entertainment venues like ours (The Henry Ford) is essential for fostering inclusive and trusting environments for our guests. Empathy allows us to connect with diverse audiences and communities by understanding their past and current experiences, and their needs and aspirations, so we can create environments and programming that resonate and empower their voices.

By prioritizing empathy and inclusivity, museums can make their programs and exhibits more accessible, sustainable and meaningful to all visitors, regardless of their background, abilities or how they engage with The Henry Ford. Leveraging admission programs, educational programming and entertainment events like our Salute to America, Hallowe’en and Holiday Nights through The Henry Ford’s Community Outreach Program, for example, creates accessible opportunities that address some of the unique challenges communities face when trying to visit.

The Invention Convention Worldwide program, which leverages data and insights from the geographic information system Innovation Atlas, identifies schools, communities and regions for participation in learning how to invent, regardless of their socioeconomic background. Invention Convention Worldwide, like other accessibility programs across our organization, levels the playing field and inspires the next generation of innovators.

By fostering and practicing a culture of empathy within your programs and mission, museums can play a vital role in addressing and supporting unique solutions to the challenges communities face, breaking down barriers and inspiring the next generation.

Empathy Through Exhibitions

Jeanine Head Miller

Curator of Domestic Life

The Henry Ford

Museums are more than places that provide information — they offer opportunities to explore new experiences and be introduced to perspectives that are not our own. As thought-provoking places, museums have an important role in nurturing empathy.

Museums provide unique, often immersive, experiences as guests stand in the presence of intriguing objects while learning their stories, or enter spaces inhabited by people long ago. There is an immediacy, a visceral quality, to this multisensory experience that conveys deeper understanding of others’ lived reality.

Museum guests feel welcome when they “see themselves” in museum exhibits. By including stories of diversity, museums embrace underserved audiences and allow all guests to see the world through others’ eyes.

The Henry Ford has expanded the stories that it tells, moving beyond a traditional lens of white, middle-class experience to encompass a more inclusive vision. Our permanent exhibits are now planned with diverse viewpoints at the center of the conversation. Recent pop-up exhibits have shared the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community, explored more deeply the African American struggle for civil rights, and presented diverse December holiday traditions beyond Christmas.

We continue to gather an increasingly diverse range of objects and archival materials that represent more broadly the American experience, reflecting differing experiences and multiple perspectives of others who share our complex world. When possible, we also capture the reminiscences of those who used the objects, preserving layers of context and personal meaning — “voices” that will continue to foster deeper understanding for guests far into the future.

The ability to see the world as others do — and use it to guide our actions — is key to creating a kinder, more just world. My hope is that museums will continue to play a significant role in cultivating empathy, creating deeper, lasting understanding that encourages a worldview that values everyone.

Empathy Through Objects

Katherine White

Curator of Design

The Henry Ford

An 18th century German secretary desk sits at the edge of the Fully Furnished exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, surrounded by examples of mostly American-made furniture. A guest might easily stroll by the desk on their way to the shiny Dymaxion House or a new temporary exhibition in The Gallery, especially if the guest is not a furniture enthusiast. But like most objects in the museum, the desk is not as straightforward as a cursory glance suggests.

A closer look at the desk (or rather, the label nearby) reveals an incredible story of the desk and its owners, their persecution and survival as a Jewish family in Nazi Germany, and the family’s journey to America with all their belongings — including this heirloom desk.

This object, like all others in the museum, is really about people.

Museums are about people. The objects exhibited within them were created by people. People used these objects, invented them, selected them, cherished them, passed them down to their children, or perhaps sold them at a garage sale. Objects are powerful — they embody the stories of people. Objects have the power to transport us to another’s perspective and in doing so, create empathy for others both like and unlike us.

Museums are one of few public institutions that the public continues to find trustworthy. We have an incredible opportunity to cultivate empathy in the public through acquiring and exhibiting objects that tell a variety of stories. How challenging it is to demonize a group of people when encountering an object that illustrates their humanity!

We continue to work toward acquiring a more inclusive and diverse collection of objects, which will then become the basis for more inclusive exhibitions, programs and experiences for our guests. In the not-so-distant future, I hope that every person can see themselves reflected within this museum — and that every person encounters a perspective different from theirs, too.

Empathy Through Outreach

Anita Davis

Program Manager, Community Outreach & Engagement

The Henry Ford

Museums have a tremendous opportunity to inspire, empower and uplift underrepresented and minoritized groups. Oftentimes the stories of these groups are marginalized to trauma and oppressive snippets of their history. It can be much harder for certain communities to find hope and inspiration when there isn’t a balancing of hardship with celebration or unjust with equity in the storytelling of their history. This oversight has the potential to lead to mistrust of cultural and educational institutions.

the flipside, by not providing a holistic view of a particular community’s history, those on the outside may come to a misinformed conclusion. By having balanced storytelling, society can show more compassion toward one another, draw on similarities while also celebrating the uniqueness of others.

Through The Henry Ford’s Community Outreach Program, we are intentional about sharing the mission and work of our community partners. Our partners represent a vast variety of service organizations that support communities with great need and little resources. By spotlighting these organizations, our various networks can find personal connections, be inspired and hopefully decide to get involved. It’s important for us to create an environment of empathy and not pity. Pity can position someone as superior and the other as inferior. We combat this by providing opportunities for resource sharing and collaboration between corporate partners, communities partners, donors and The Henry Ford staff. We have learned that collaboration and intentional engagement among networks can lead to shared compassion for the well-being of a particular community.

My hope for the future is that The Henry Ford continues to build toward creating a more honest, inspirational and welcoming environment for all communities represented in our collection. Given the nature of our institution and the position it holds, we have a huge responsibility to ensure that we don’t misrepresent the people whose stories have been historically minimized.

Henry Ford is such a unique experience. We can truly be that community conveyor that inspires other cultural institutions to rethink how they tell stories and engage with surrounding communities.

Empathy Through Leadership

Mike Moseley

Director of Leadership and Talent Development

The Henry Ford

I always tend to look at things from the perspective of what’s the responsibility of leaders. It’s my job. As the director of Leadership and Talent Development, I will tell you that empathy is a vital leadership quality that benefits both individuals and organizations. By understanding and connecting with others, empathetic leaders can create a positive and productive work environment, drive innovation and build strong relationships.

So, as that applies to our work as museum leaders, using the ability to understand and share feelings of others helps people connect to their history, heritage and the world around them. A leader who can deeply understand and connect with the diverse audiences they serve — both staff and The Henry Ford guests — is better equipped to create meaningful experiences and foster a sense of belonging that is necessary for authentic storytelling.

Museum leaders who act empathetically attract people from all walks of life, with varying backgrounds, interests and experiences. A leader who can empathize with these diverse audiences can better understand their needs, desires and perspectives. This understanding allows for the creation of exhibits and programs that resonate with a wider range of people.

Empathy fosters trust and connection between leaders and their staff, volunteers and community members. When people feel understood and valued, they are more likely to be engaged and supportive of our institution’s mission.

The Henry Ford should be a welcoming and inclusive environment for all. We are continuing to work on that.

By empathizing with the experiences of marginalized communities, our leaders can ensure that our collections, exhibits and programs are representative and respectful of diverse perspectives.

The world is constantly evolving, and we must adapt to stay relevant. Empathy helps leaders to anticipate and respond to changing needs and preferences, ensuring that The Henry Ford remains a valuable resource for the community.

believe the ongoing commitment we have to strong leadership development at every level, and the institution’s commitment to creating a safe and diverse work environment, are steps that we are taking to build a more empathetic culture.

Empathy Through Performance

X. Alexander Durden

Manager, Theatrical & Musical Experiences

The Henry Ford

I have always wanted to push limits. Take things that I have learned from my life experiences and apply them in a different context. It’s what has opened my artist worldview.

Early in my hiring process in 2023, I asked about what programming we had on the African American community, Native Americans or the Middle Eastern population. For me, The Henry Ford provides an incubator where we can explore and talk about the stories and the people and be inventive about the ways in which we do it.

Last January, we premiered The Beginnings of the Boycott, a piece about the events that led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in the museum. We also debuted Market Season in Greenfield Village last year. Both are multicharacter pieces.

I noticed early in my time that a lot of dramatic programming was a single actor speaking first-person to the audience. Many times, we like watching a movie or attending a play because we have the opportunity to peek into a situation and observe, we get to pick up on the in-between, the nuances of the characters and the way they communicate with one another.

With Market Season, for example, we researched the historic multiculturalism of Detroit and focused on three Detroit Central Market figures in the late 19th century: market staple Mary Judge, Jewish fishmonger and activist Itzak Danto and James Kanada, the first Black frontiersman. We felt it was important to uplift these pillars in our local history by telling their connected stories.

Visitors often respond, “Oh! I didn’t know this person was real.” We are starting conversations, which is important because we want people to know these individuals beyond their biographies. We want guests to see how they existed together and the subtext to the relationships now on display. Visitors are definitely picking up on it.

Beyond dramatic programming, we have established our new performance series in the museum and village. Music in the Market and Arts & Artifacts highlight different musical acts, often based on designations like Jewish Heritage Month or Hispanic Heritage Month.

Not only are people being entertained, but they are also learning, being exposed to something new. That’s powerful because although our communities are quite diverse in the metro Detroit area, we don’t cross lines very often. We don’t ask questions. That’s why we’ve encouraged our guest artists to talk about their instruments, talk about their culture and the origins of their performances with guests.

Our job as a museum is not to preserve history but to provide context to history. Artifacts are only jumping-off points. We must talk about what and who led to innovation, what was the need that had to be met.

For hundreds of years, we have been interested in entertainment. We consume performances to feel what is an ideal or unideal human experience. We hunger for empathy or something we can empathize with. At The Henry Ford, I think we need to continue leaning into the uncomfortability. To appropriately contextualize history, we must talk about things that make us uncomfortable. How do we do that? Very carefully. Arts is a fantastic way to start conversation. Art speaks when words fail.

My hopes for the future... that we continue to activate other artifacts in our collections, find more common ground, and unearth and explore our differences because that allows usto understand the full range of humanity.

I am excited, thankful and hopeful that I can continue to contribute as much as I learn.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

A Symbol of Courage

The Jackson House: a Curated Story from Selma, Alabama, to Greenfield Village

At the end of last summer, the story of the Jackson House, a landmark symbol of the Long Civil Rights Movement, took a historic turn. On Maple Lane in Greenfield Village, initial repositioning of the more than 100-year-old structure began, marking the next chapter in a meticulous reconstruction project. With its relocation from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan, the Jackson House is set to give millions of visitors to The Henry Ford the opportunity to hear stories of family, friendship, leadership and Selma’s role in one of the most momentous movements in U.S. history — the organized 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches that helped ensure all Americans would have the civil rights and voting rights promised to them.

Photo by Brian Egen

It was Dr. Sullivan Jackson and Mrs. Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson who opened their Selma home to close friend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his allies in Dallas County and nationally as a place to rest and strategize the path forward to secure voting rights for African Americans. Hundreds of people came through the home, including several Nobel Peace Prize winners, international dignitaries, media representatives, and activists and supporters of civil rights for all. This activism helped lead to the passing of the Voting Rights Act in June 1965.

Much work still needs to be done in the home’s reconstruction in Greenfield Village, which first required preparing the site between the George Washington Carver Memorial and the William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace. Last fall, further reassembling of the house’s structural components, such as its covered front porch, commenced. Over the coming months, the roof will be replaced, floors and walls repaired, electrical and plumbing systems connected, central heating and air-conditioning will be installed, and fire protection and security systems will be added.

Less visible, yet just as critical, behind-the-scenes work also continues, said Amber N. Mitchell, The Henry Ford’s curator of Black history. “The home will look much different than what it appeared in Selma before the relocation,” she said. “We are renovating it to look similar to what it did around 1965, and there are many ways to interpret that time period that we are investigating.

“This is a true collaboration,” she added. “A combination of the actual structure reconstruction, our historical resources and great detective work on the part of our curatorial team and staff to ensure the Jackson House’s story of family and community is as uplifted as the connecting story of the voting rights movement.”

A public opening of the restored Jackson House in Greenfield Village is currently planned for June 2026.

This post was written by Jennifer LaForce and adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

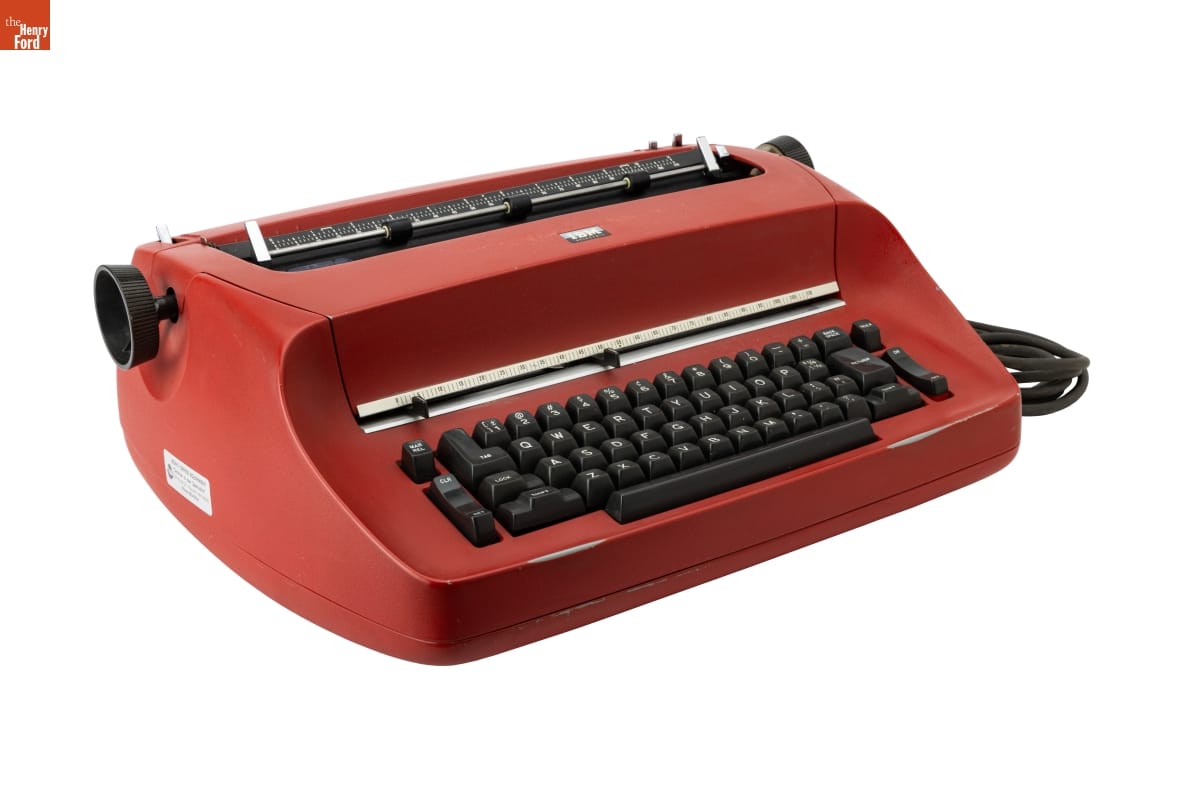

IBM Selectric Typewriter designed by Eliot Noyes in 1961. / THF802461

In August 2024, a monumental design collection arrived at the doors of The Henry Ford after an international journey nearing 600 miles. The collection was donated by the Stewart Program for Modern Design in Montreal, Canada, and represents decades of collecting by founder and philanthropist Liliane Stewart alongside her incredible staff, especially curator David Hanks and registrar Angéline Dazé. While Liliane Stewart and her husband, David, had a longstanding formal relationship with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (a pavilion named for the Stewarts houses a significant design collection donated by them in 1999), this portion of the considerable collection was offered to The Henry Ford upon the closing of the Stewart Program for Modern Design in 2024.

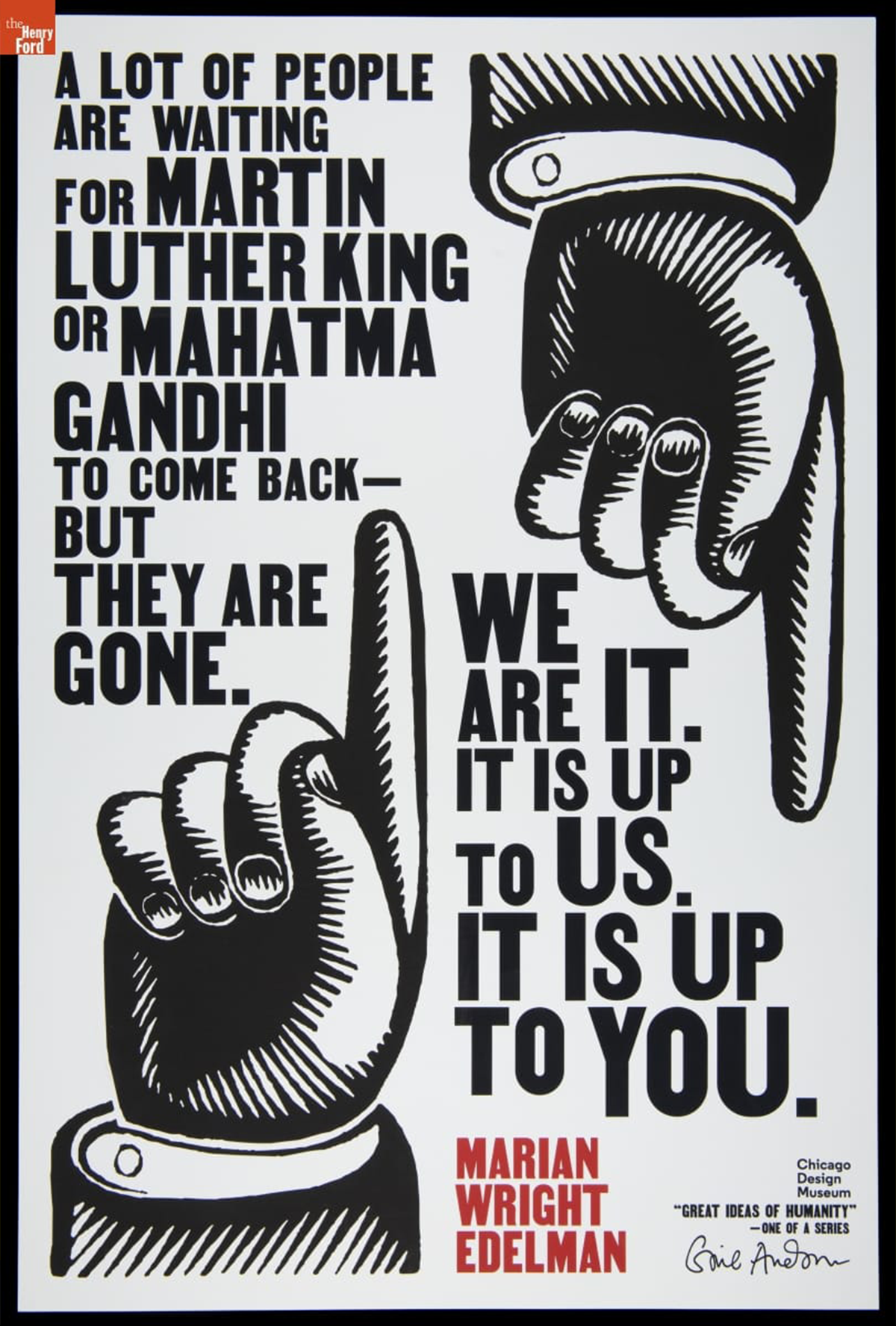

This poster, entitled “A Lot of People are Waiting for Martin Luther King... We Are It. It is Up to Us. It is Up to You. Marian Wright Edelman” was created by graphic designer Gail Anderson in 2018. / THF721539

The Stewart Program Collection at The Henry Ford includes over 500 objects, a library of more than 100 books and 500 periodicals, and an archive nearing 40 linear square feet. As design touches nearly every area of the museum, so too does this collection. The range in object type is vast — from ceiling lamps to bicycle helmets, teapots to stools, studio glass to adding machines and more, and spans over 140 years of design history, from the 1880s through 2020. The designers and companies represented in this donation are also remarkably wide-ranging and include some of the most celebrated names in design, as well as successful works by unknown designers. They were created by designers of various nationalities and manufactured in a range of countries —but every object had significant impact on American society and American design, through its retail availability on the American market or through its prominence and influence on American designers, reflecting the trajectory of globalization in design.

“Alaska” Vase by Italian designer Ettore Sottsass, 1982 / THF802469

The Henry Ford and the Stewart Program for Modern Design have compatible philosophies in collecting design. Both institutions hold a deep respect for design’s role in the everyday lives of people, in the problem-solving nature of good design, and the practice of prioritizing design in its cultural context. The Stewart Program Collection fits serendipitously within the museum’s existing holdings, while also stretching, expanding, and deepening the collection as well as pushing into new areas.

This Model 4706 Electric Clock, 1933-1934 by Gilbert Rohde was exhibited at the 1933-1934 Century of Progress International Exposition with the 3317 series furniture collection, also designed by Rohde. The Henry Ford holds numerous pieces from the 3317 series, including this dresser which is on display in the Fully Furnished exhibit. / THF802510

Collections Connection

In numerous instances, the objects donated by the Stewart Program happily supplement the strengths of our collections. For instance, The Henry Ford has an especially strong collection of furniture by pioneering designer Gilbert Rohde for the Herman Miller Furniture Company, including much of the bedroom set Rohde designed for the “Design for Living House” at the 1933-1934 Century of Progress International Exposition. However, we lacked the table clock exhibited in the bedroom. But as luck would have it, that particular clock was included in the Stewart Collection donation. Reuniting these objects that were designed to coexist will allow us to tell a fuller story about this moment in design history.

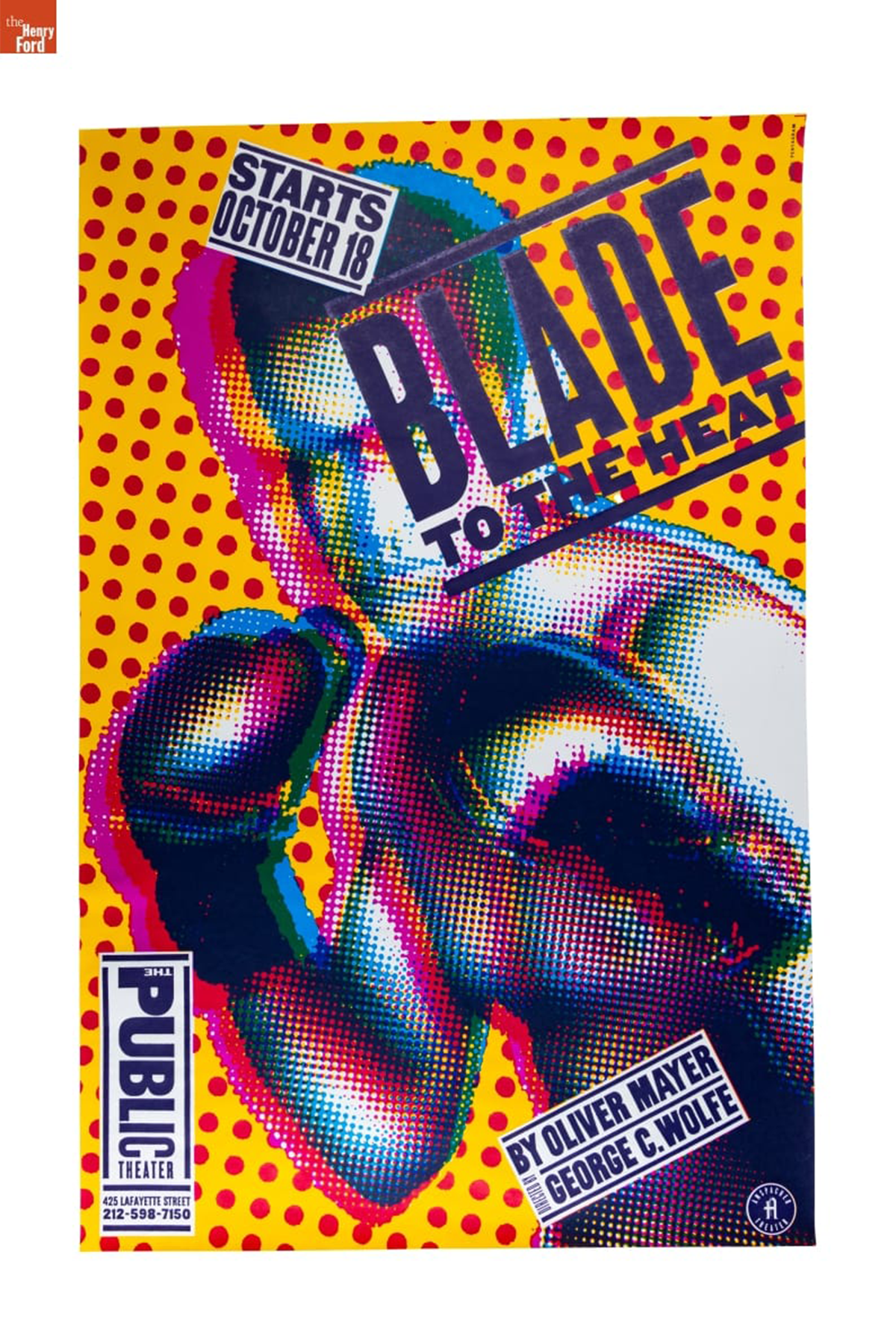

Numerous posters designed by Paula Scher were donated by the Stewart Program for Modern Design, including this “Blade to the Heat” poster designed for the New York Public Theatre in 1994. / THF802482

Designed by Women

In 2018, the staff of the Stewart Program for Modern Design embarked upon their Designed by Women project, which encompassed an ambitious new acquisitions program of objects designed by women, an expansive website, and digital exhibitions. Highlighting women designers across the globe from 1910 to 2024, the project has become a resource for the design profession as it showcases both well-known and lesser-known designers. Similarly, The Henry Ford has been working in recent years to expand representation of women in the design collections, with recent acquisitions like Lucia DeRespinis’ Beehive Lamp, Evelyn Ackerman’s Campesina Tapestry, and Gloria Caranica’s Rocking Horse. Many of the objects acquired by the Stewart Program for Modern Design for this project were donated to The Henry Ford, expanding our collection of objects designed by women, including a large collection of posters by pioneering graphic designed Paula Scher, a teapot by Edith Heath of Sausalito, California-based Heath Ceramics, a pendant necklace by Indigenous jewelry artist Angie Reano Owen, and many more.

Paula Scher’s “Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk” Poster, 1995 (left), Edith Heath Teapot, c. 1944 (center), Shell Necklace by Angie Reano Owen, 2014 (right). / Images courtesy of the Stewart Program for Modern Design

Check out the Selections from the Stewart Collection expert set for more information about some of the objects donated by the Stewart Program for Modern Design.

Eva Zeisel’s “Town & Country” Teapot, Teacups, and Saucers, c. 1945 / THF802477

Katherine White is Curator of Design at The Henry Ford. This blog post was adapted and expanded from the January-June 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

A Storyteller’s Perspective

Author and filmmaker Nelson George leans into a discussion about how obstacles, objects and observation are the makings of a good story

Nelson George has had an amazing career. He’s an author. A screenplay writer. A filmmaker. An award-winning journalist. And he’s not done yet.

Photo by Erik Tanner/Contour by Getty Images

Broadly speaking, much of George’s professional portfolio has been focused on the documentation of the Black experience in America. His publication record includes both novels and celebrated nonfiction works like Where Did Our Love Go?: The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound and Blackface: Reflections on African-Americans and the Movies. He also has credits as a writer and producer on Netflix's The Get Down and has co-written screenplays for iconic 1990s films including Strictly Business and CB4 starring Chris Rock.

Over the decades, George has built upon his skills as a prolific storyteller. He has an unwavering understanding of the human condition from myriad angles and readily relies on his keen observation skills to bring stories of people overcoming obstacles and realizing their dreams to the page and screen.

Recently, Kristen Gallerneaux, curator and editor-in-chief, and Jennifer LaForce, The Henry Ford Magazine’s managing editor, had the opportunity to talk with George as he begins to contemplate and activate his approach to documenting the next chapters in the story of the Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson House, one of the newest acquisitions of The Henry Ford. This Selma, Alabama, home provided a safe haven where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and hundreds of others invested in the Voting Rights Movement worked, collaborated and strategized the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965 (learn more). George will be creating a documentary about the house’s significance to the Long Civil Rights Movement, the backstory of its move from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan, and its reconstruction in Greenfield Village (learn more).

Kristen Gallerneaux: You’ve worked within many forms of media during your career — as an author, a screenplay writer, filmmaker, documentarian, journalist. What have you learned about people and their relationships with one another?

Nelson George: The way that people relate to each other is through story. Think about the people we meet. We ask where they’re from. They tell you “I came from here. I went there. I got married. I got divorced.” Whatever our stories, they are the unifying way that we communicate with each other.

In any medium I work in — whether it’s a book or a movie or a documentary or some other form of storytelling — it’s all about finding the beginning, finding the middle and finding the end. And I think that people relate to each other best when they feel there’s a story that they can connect to.

It’s kind of funny. I do a class once a year in London at different institutions for young artists. It originally started out as a screenwriting class. What I’ve noticed over time is that there are so many different technologies at work today to tell a story — from TikTok to AI — but ultimately it’s about engaging people. I try to teach that if you start off with a star, and then tell how that star was born and then share that star’s journey, that’s the best way to engage someone. For me, the one thing I take away from all the different work I’ve done in all the myriad of forms is that whether it’s about love, an athlete or politics, people really connect when you’re able to communicate in a story form. Tell a story well, and you can bring almost anybody into your world and into your space, and make them connect with you.

Jennifer LaForce: What are some of the nuances of successful storytelling? Those skills and expertise that you use to make that connection with people?

Nelson George: It’s all about the obstacles, because obstacles create goals. When you engage with anybody’s story, whether it’s Willie Mays coming out of the Jim Crow South trying to become a major league baseball player or Michael Jackson who is making an album and knows that the record industry and formats like MTV are very reluctant to play Black artists. Or if it’s Tupac Shakur. Working as an executive producer on the Dear Mama docuseries (editor’s note: focused on the lives of activist Afeni Shakur and her son, musician Tupac Shakur), there were a big number of challenges to explore. Not only how do you overcome a life of poverty, but also your mother is a political figure — and a radical political figure at that — and how does that jive with your commercial career as a recording artist? What are the contradictions in that?

Anytime you have a story with an obstacle, it’s about the “what happens next.” People are like, “Oh, what are you going to do?” Overcoming is a huge part of storytelling. It’s like when you have a love story. It may always end with the wedding, but there’s a whole bunch of obstacles in-between — whether they’re family, racial, financial, distance — before they’ve reached the goal. That’s why love stories are so compelling because we know the outcome we want to see, but what we want to know is “how do they get there?”

Kristen Gallerneaux: Speaking of obstacles, you’ve handled some of those stories rooted in the music scene. Thinking, for example, about your book Where Did Our Love Go?: The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound. Why is it important in storytelling to understand what it means to be true to yourself?

Nelson George: I’m not sure that most people know what their authentic self is. I don’t think they know until they do something. It’s only in action that character is really truly defined. Decision reveals character, and so in any narrative, those moments of decision are the crucial ones.

I’m currently working on a book about a neighborhood in Brooklyn in the ‘80s and ‘90s that [film director] Spike Lee came out of, and the many decisions Spike made during this time. One that was the most important for the neighborhood was that while most young filmmakers with a successful first film would have gotten an office in Manhattan to run a production company, he decided on a spot, literally, like five blocks from his house. By having the production company in Brooklyn in 1987, it helped transform the neighborhood. People had to come to meetings in Brooklyn. His crews wanted to be close to where the work was, so they moved to Brooklyn. Actors working with Spike started staying in the neighborhood. All of a sudden, the neighborhood becomes “cool,” because Spike is there.

That one decision against the orthodoxy, which is Manhattan, has a tremendous effect on a neighborhood and a generation of artists. Some make the argument that Spike deciding to stay in Brooklyn is one of the key things that led Brooklyn to becoming this kind of cool cultural center.

It’s about decisions you’re making, not knowing what the ramifications are going to be later down the road, right? There’s a certain fearlessness to it. There are always unintended consequences of your decisions — sometimes good, sometimes bad — but when we make decisions, we’re making them based on the information we have and in light of our own desires. You just never know what that’s going to do, how that’s going to ripple.

Picking up further on that … You know Berry Gordy could have decided he’s just a songwriter, and he’d have been a success. He’d written songs for Jackie Wilson that were hits, and he could have easily moved to New York and tried to get in the Brill Building and become one of those songwriters. Instead, he opened up the spot [Motown’s Hitsville U.S.A.] on West Grand Boulevard. He made a decision to stay home, and that decision transforms his career — and Detroit.

Kristen Gallerneaux: It’s amazing the breadth of publications that you have, shifting between fiction as well as really deep, scholarly nonfiction and these poetic portraits of well-known characters. And let’s extend that out to your screenwriting credits as well — I know that you worked on The Get Down and Strictly Business, which is iconic. Have you ever had difficulties bringing a character or a subject to life? And on the flip side of that, how do you do it, functionally?

Nelson George: I think it goes back to obstacles. On The Get Down, for example, we had these young artists who were not even really artists yet. They were just kids who wanted to perform or wanted to get out of the Bronx. One of the things we did in the first episode was to introduce a record — the rarest record in New York. That “device” then allows you to meet the lead characters in the story.

Baz Luhrmann, who executive produced The Get Down, came into our office one day and he did a whole lecture on devices. Devices, in a film way, is an object of desire, or for the characters, an object that becomes symbolic of a larger search for identity. It’s a really great technique in terms of trying to figure out how to get a story going. Give someone a goal, but not just a general goal — a specific goal that involves an object.

Think about The Maltese Falcon, the famous detective story. Or the guy in Citizen Kane. He’s looking for Rosebud. If you look at classic literature, classic films, often there is a device or a thing that actually becomes the “way” or what people are looking for. In The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, it’s about these rings. They’re tangible. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing is about the pictures on the wall of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria in Brooklyn.

You have characters, you have goals, but what embodies them is wrapped around tangible pieces.

Kristen Gallerneaux: In The Get Down, it would also be the turntables and equipment that you need to learn to DJ, right?

Nelson George: Right! That’s tangibility. You have a goal and you’ve given your characters an object that becomes a representation of all their dreams.

Kristen Gallerneaux: I love that. It’s really interesting too, because people, even once they acquire that object, they make choices and decisions that can sway their life in any number of directions around that object. The goal tied to objects allows you to create character.

Nelson George: Yes. In general, I like to use reality to create. It’s where I’m more grounded. I’m taking from life, right? That to me is looking at things that have been done and seeing if there’s a way to do them differently. For example, I did a bunch of detective or noir novels. The first was called The Accidental Hunter. Basically, I saw the movie The Bodyguard with Whitney Houston, and asked myself, “What if she was white and the bodyguard was Black?” That very simple thought led to me writing that novel, and that led to me writing five more novels with the same character. Sometimes it’s just a matter of seeing something that was good or interesting, and looking at it from a different angle.

Jennifer LaForce: Not everyone is capable of that type of foresight or observation. Would you say you have strong observation skills?

Nelson George: That’s the beauty of growing up in New York: great people-watching. You can sit on a bench in the summertime or, for that matter, be on the subway and see so many people. “What kind of sneakers is he wearing? I’ve never seen those before.” You see a woman who’s got a shopping bag and you can tell that her nails have not been done in a while, and you go, “Oh, she’s a mother or working-class woman. She hasn’t had time to do her nails because she’s busy.” You start observing people, what’s particular about their attire or their body language and stories can begin to come from that. New York has been big in terms of the observation part of my career.

Jennifer LaForce: Were you always that observant person? That person who wanted to tell a story?

Nelson George: I remember reading Hemingway, The Nick Adams Stories, and thinking, well, he’s writing about a kid living in Michigan, and it’s very detailed. You know that Hemingway style — very descriptive — and you had to read through what he was seeing and feeling. That really stuck with me. When I was about 15, 16, 17, I started writing stories based on a character living in Brooklyn, and it was totally because of reading Hemingway and trying to mimic the masterful style. It definitely put me on a path that understood how external details of a place and of a person can be incredibly revealing. I give Hemingway a lot of credit as one of my influences in terms of harnessing observation.

Kristen Gallerneaux: As a seasoned storyteller, why is it important for us to tell stories of our past, keep our histories at the forefront?

Nelson George: History is a tool to understanding how we got to the places we are. I think that Americans in general have a very superficial sense of history, and they tend to make the same mistakes over and over again.

History can be extremely instructive in understanding why we’re in the positions we’re in, economically, culturally, government wise. At the same time, there are techniques that were employed in the past that are still applicable now. Yes the technology changes, but I don’t think the human condition changes necessarily as deeply, so there are ways in which we can use ideas and philosophies of the past to move forward. I also think history allows us to “see.” Going back to my comments about obstacles, we can see how obstacles that got in the way of individuals were overcome. That’s where the inspiration part comes in and where history can be so useful.

Any museum, particularly ones that are collecting objects from the past, can really inspire people, too. The scale of The Henry Ford is really kind of stunning in terms of that.

Kristen Gallerneaux: Yes! I think not only the scale but also the breadth of the collections of The Henry Ford are sometimes a shock to people. What role do you see institutions such as The Henry Ford playing in the documentation of everyday Black and African American culture and history?

Nelson George: We talked about Spike’s decision about Brooklyn. We’ve also talked about Berry Gordy in Detroit. These buildings, these sites, are really only significant because of a person’s decision to use them as a headquarters for potentially historic things.

At The Henry Ford, I see a building like the Jackson House representing a similar significant location.

Why was this place selected and why did Dr. King and his advisors think it was the right place to be? How did the Jackson family create an environment supportive of these efforts? How did their daughter, Jawana Jackson, realize the value of what happened in her home and document it and preserve it the best she could for over 50-plus years?

Greenfield Village has so many spaces like this that represent different moments in American history — that represent the efforts of hundreds of thousands of people to create a better America. Hopefully the Jackson House project will pay tribute to the efforts that took place there and the efforts that were made to maintain this structure.

Kristen Gallerneaux: We’re so lucky that Ms. Jawana Jackson and her husband, James Richie, believed in this project and maintained stewardship of the house and its stories over such a long period of time. I’m sure there were points of exhaustion as they dealt with the ambivalence that brought the house from Selma to Detroit in the first place.

Nelson George: In retrospect, they were not getting a lot of support from the state of Alabama. And those specific obstacles, they will definitely be a part of the storytelling of my film. What happened? Why was the house not supported? It’s one of the ways I hope to create empathy for Jawana’s and her husband’s efforts in the face of great indifference.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Office Staple

Designed decades ago, the Aeron Chair remains a wonder of ergonomics.

Even while seated, people tend to crave motion. Chairs that move — by rocking, reclining, rolling, revolving or otherwise — are often the most comfortable chairs because they respond to the body. This principle was one of many incorporated into the study of ergonomics, or the science of designing products and environments for compatibility with the human body.

In the 1960s, ergonomics began to gain traction with industrial designers. Bill Stumpf came of age as a designer during this period and became interested in ergonomics in the late 1960s while a postgraduate at the University of Wisconsin. He studied existing ergonomics research by designers as well as the work of scientists, doctors and medical researchers. Stumpf applied these scientific principles in the design of his first office chair for the Herman Miller furniture company. Called the Ergon Chair (short for ergonomic), it debuted in 1976 as the first truly ergonomic office chair.

Perhaps the best-known ergonomic office chair, the Aeron Chair, was also designed by Stumpf in partnership with Don Chadwick. Office workers spend hours seated at a desk, mainly since the rise of personal computers, and office chairs before the 1970s often did more harm than good to their inhabitants. Stumpf and Chadwick endeavored to design an ergonomic office chair that built on the lessons they learned in developing their previous chairs, especially their Sarah Chair, which was designed for the elderly to mitigate the bodily impact of sitting for long periods.

Photo by EE Berger

The Aeron Chair was released in 1994 to immediate acclaim. The seat of the chair uses an elastic plastic mesh, called pellicle, to replace the foam cushions of a traditional office chair. A tilt mechanism, with adjustable components, provides opportunities for movement, even at rest.

Although the Aeron Chair turned 30 years old this year, it is still regarded as the gold standard in office chairs — its ergonomic design continuing to serve the needs of office workers around the world.

This post was written by Katherine White, curator of design at The Henry Ford, and adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2024 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Mining Affordances

Skateboarding can change how we see and interact with the world

By Roy Christopher

I don’t know any casual skateboarders. Everyone I know who’s ever done it has either an era of their lives or their entire essence defined by it — the rebellion, the aggression, the expression.

Inextricably bound up with your being, it’s the way you wear your hair and the way you wear your hat. It’s the kind of shoes you wear and which foot you put forward. It’s the crew you run with and the direction you go. There is something about rolling through the world on a skateboard that changes people forever.

Ever since I first saw Wes Humpston’s Dogtown cross on the bottom of a friend’s skateboard in the sixth grade, I knew it was going to be a part of my world. I first stepped on a skateboard at the age of 11. There are scant few physical acts or objects that have had a larger impact on who I am and how I am. Through the wood, the wheels and the graphics, skateboarding culture introduced me to music, art and attitude. Like Dischord Records co-founder Ian MacKaye said to journalist Dan Sinker in 2001, “Skateboarding is not a hobby.” More than 20 years later when I interviewed MacKaye myself, he further elaborated. “It was a discipline. It was the way that we learned how to navigate our surroundings, and the world was transformed by this navigation because we suddenly saw everything a little bit differently than it had originally appeared.”

Photo by Adobe Stock

Riding a skateboard fundamentally changes the way you see the world and yourself in it.

Sport vs. Lifestyle

Skateboarders have always found their own use for everything in the city. First, it was surfing the open waves of sidewalks and streets, as cited in Iain Borden’s Skateboarding, Space and the City. Then the challenges of the steep walls in empty backyard pools beckoned. Eventually, street skating found affordances in everything: ledges, curbs, stairs, handrails — edges and angles of all kinds.

Even with the proliferation of skateparks, pure street skating remains a true measure of skill and vision. As pro skateboarder John Rattray shared in a Nike SB interview, “It’s been game-changing for me to learn how and why the actual movement of skateboarding helps us to neurologically regulate.”

Skateboarding culture highlights the inherent adolescent tension between wanting to be an individual and wanting to belong to a group. It’s a brand of cognitive dissonance emphasized in the still-growing pubescent brain that peaks with the rapid growth and nagging confusion of young adulthood. Miki Vuckovich, a photographer and fixture in the skateboarding industry, once told me, “Skateboarding is a rebellion. It’s a sport, an activity, a lifestyle adopted primarily by adolescents, and as an individualistic activity, it gives participants a sense of independence. It sets them apart from others who don’t skate, and their own particular approach to skateboarding further differentiates them from their skating peers.”

I liken it to the notion that when different innovations and situations exist in your world, your brain changes. New knowledge and new tools physically and chemically alter the makeup of what’s in your head — our brains are different when different inventions come to be. That is, we have different thoughts and dreams after certain ideas and innovations seep into our world. We simply see things through a new lens.

Photo by Adobe Stock

According to Raphaël Zarka’s On a Day with No Waves, riding a skateboard changes how one sees the world generally and the built environment specifically. Where most see streets, sidewalks, curbs, walls and handrails, skateboarders see a veritable playground of ramps and obstacles to be manipulated and overcome in the name of fun. Hills are for speed. Edges are for grinding or sliding. Anything else is for jumping onto or over. Looking through this lens, all one sees are lines to follow and lines to cross. It’s a familiar story to skateboarders, the before and after, because skateboarding redefines everyone who does it as well as the way they see and interact with the world around them.

Minding the Gap

Game designer Brian Schrank defines affordance mining as a way of determining a technology’s “underutilized actionable properties and developing methods of leveraging those properties.” An affordance, according to famed American psychologist James J. Gibson, is simply an object’s capacity for use, the operations or manipulations it will support. Schrank mined affordances most famously from computer keyboards, designing games that challenge the use and user of QWERTY keyboards to find new ways of interacting with the common computer. Schrank’s game Hello Zombie Mouth, for instance, involved mashing the keys on a keyboard to control a mouth as it yawns and stutters trying to say “Hello.” For the game, six regions of the keyboard were mapped, each to a phoneme. A few attempts with such a haptic puzzle quickly demonstrate the untapped potential of such everyday devices for not-so-everyday applications.

One can find the same untapped potential when applying these techniques to ourselves — internally as well as externally — as well as to skateboarding. Explained pro skater Rattray, “Skateboarding requires intense focus, even when we’re doing a trick we’ve done thousands of times, there’s a level of focus — what is the ground like, where are the cracks, how can I adjust my weight, how much speed do I need? And you do this all through the physical sensation. It forces us out of our thoughts and into our body.”

After suffering bouts of depression yet not knowing what he was experiencing, and then losing his sister to suicide, Rattray began the campaign Why So Sad? in 2017 to drive awareness, education and fundraising around mental well-being and suicide prevention in the skate community. He continued:

One of my main points of contention with this subject we call ‘mental health’ is the idea that it is somehow separate from physical health. Like it’s some different weird thing that we can’t understand or even see, so we must be afraid of it. And then the toxic idea that if we are tarred with the mental health brush, then we are done for, damaged goods, and we can’t ever heal. This is physical stuff we’re working with here. It’s neurochemicals, your endocrine system, dopamine, cortisol, adrenaline, and all the rest of it.

Photo by Adobe Stock

The reconciling of physical with mental health is paramount, realizing your own physics as a skateboarder, an athlete, a person. Fellow pro skater Nicole Hause flipped it, sharing thoughts in her Nike SB interview, “The more therapy you do, and the more time you spend with it, the more it compounds; you understand it, and it becomes easier. It’s a skill you learn like skateboarding.”

Learning to work through what Hause calls “stuck points,” like you’re trying to kickflip down some stairs or grind a long ledge, is a personal triumph, appropriating the affordances of your own mind in similar ways to that of skateboarding the streets.

“Skateboarders, particularly adolescents, seek identity,” added photographer Vuckovich. “They want to be a part of a community that reflects what they’re feeling or how they see the world.”

Skateboarding changes the world by changing the mind. Skateboarding works constantly against the limitations of the built environment. Skateboarding is where the predictions of design and the desires of humans diverge. Skateboarding is where the body and the brain move together to overcome obstacles. Repurposing terrain made for other things and remolding the mind in the process, skateboarding is a reinterpretation of the affordances of the world.

This post was adapted from an article in the Summer/Fall 2024 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

What’s the Role of Digital Media in the Museum Experience?

The simple answer: to tell a meaningful, engaging and informative story. But we could say the same for any exhibit component. Exhibit labels and signs meet those criteria, as do videos, artifacts and our skilled presenters. For an exhibition designer, the question is more complex and depends largely on the situation. Digital media is just one of many experiential techniques to choose from.

Being informative is easy. A white label with black text stating the birth date of a historical figure provides sufficient information. In some cases, it’s exactly what’s needed. A more challenging task is making the informative engaging and therefore meaningful. To do this, we must find the best storytelling device that allows us to connect to universal ideas where all individuals — within our wide spectrum of guests — can find relevance.

Digital experiences excel in areas where there’s a need to convey complex or layered information, attract through novelty and fun, or respond with flexibility and adaptability. Virtual exploration — by simulation or transportation — has the magical ability to whisk our guests beyond the confines of our campus (or bring them to us) and put them into situations they may never find themselves in, such as walking on the wings of an airplane or working on a racing pit crew. The possibilities are nearly endless, and emerging technologies are ever widening the imagination. I’m sure an AI chatbot would have lots to say on the subject.

Despite the many exciting opportunities with digital, it isn’t always the best choice. Hardware and code evolve at a rapid pace, and keeping up can be costly. We also consider how our museum experiences are unique in 2024 when many of us live entrenched in a digital world already. Our ideal exhibition experience is one where guests don’t notice the methods — and the complex questions feel like they have simple answers.

Written by Wing Fong, director of Experience Design, The Henry Ford

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2024 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Moving Boldly

Dancer Martha Graham was formidable in her work, art and life.

Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in 1894, Martha Graham first became captivated by dance when, at 17 years old, she saw Ruth St. Denis — known even then as a pioneer for drawing influence from Asian dance forms — perform in Los Angeles. In 1916, Graham joined the Denishawn dance troupe (co-founded by St. Denis and her then-husband and dance partner, Ted Shawn), and began a performance career that would continue until her retirement from the stage at age 74.

In 1926, Graham founded the Martha Graham Dance Company with herself as principal choreographer. Her work would come to define modern dance, with her technique creating the first teachable methodology. Eschewing the delicate, airy aesthetic of traditional ballet, Graham’s choreography was grounded, focusing on the contraction and release of the body, originating in the solar plexus. Sharp, sometimes harsh movements, interrupted by moments of spiraling fluidity, were used to convey an emotional reality in each performance.

Early in 2024, The Henry Ford acquired five color slides documenting the creative collaboration between Graham and designer Isamu Noguchi. Noguchi designed sets for over 20 of the company’s performances (including Graham’s most notable work, Appalachian Spring), his spare but innovative designs pairing perfectly with Graham’s choreographic style. The images capture dancers in action among Noguchi’s set pieces, evoking the energy and reality of the performances in a way that programs or other ephemera would not.

Slide images from performances of (clockwise from bottom) Acrobats of God (1960), Seraphic Dialogue (1955) and Frontier (1935). Photo by EE Berger.

Martha Graham’s importance lies not just in her choreography; the same thread of boldness ran throughout her life. Years after her death in 1991, she is remembered for her forceful personality — she was known for pushing herself and those around her, inspiring in many an intense devotion to her and her teachings — and her unflinching commitment to telling feminist stories through her works, which often included unvarnished depictions of female power and sexuality.

Collecting her work — even in the smallest of images — allows The Henry Ford to explore more of Graham’s dynamic story.

This post was written by Rachel Yerke-Osgood, associate curator, and adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2024 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Industry Evolution

2024 marks two milestone anniversaries for the Ford Rouge Complex

By Paige Gilbert, social media manager, The Henry Ford

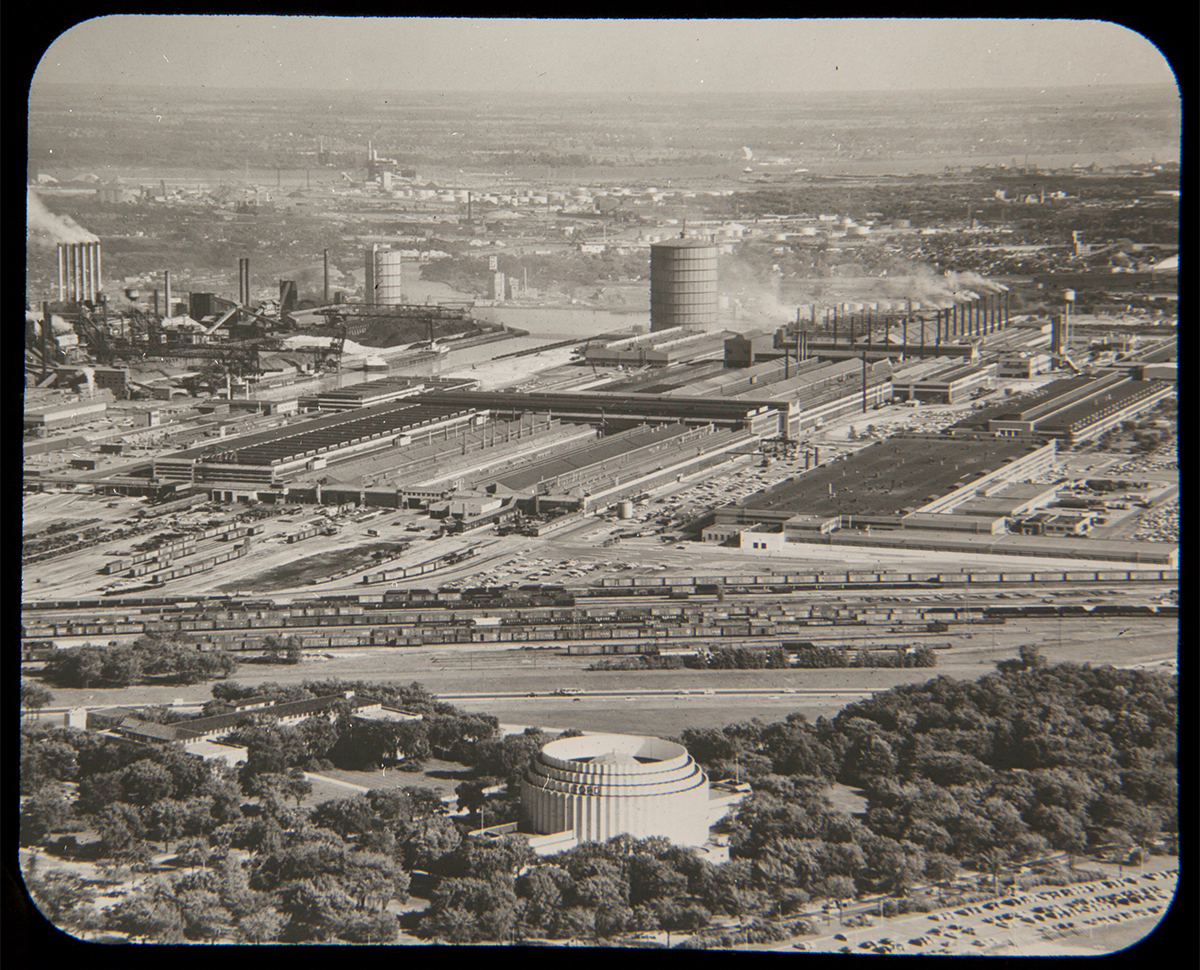

One hundred years ago, in 1924, Henry Ford opened the massive Ford Rouge Complex for the public to see and experience the manufacturing process. By 1936, a memorable phase of Rouge tours began. The Ford Rotunda — originally designed for the 1934 World’s Fair — reopened as a visitor center and starting point for tourgoers who boarded glass-roofed buses to see the massive complex. Some of today’s guests still remember walking through the steel operations plant.

Ford Rouge Complex circa 1955 / THF274424

After a 1962 fire destroyed the Rotunda, Ford Motor Company opened a building called the Spirit of Ford directly across from Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and bused tour attendees from there to the Rouge. In the early ’80s, Ford stopped offering factory tours for various reasons.

In the late ’90s, Bill Ford, then chairman of Ford’s board, began to reimagine a Rouge Complex of the future. He brought on architect and designer William McDonough to help make the Rouge more efficient and sustainable. Together, they envisioned a site that could become a model of industrial production and environmental redesign. The complex saw many transformations — including new approaches to stormwater management, landscaping, waste minimalization and lighting, as well as the creation of one of the world’s largest “living roofs.”

With this redevelopment came the opportunity to build a visitor center and reopen the factory to the public. The visitor center project came to life through a collaboration between Ford Motor Company, The Henry Ford and UAW Local 600.

Twenty years ago, on May 3, 2004, the Rouge reopened to the public, this time with tours managed by The Henry Ford. Today, Ford Rouge Factory Tour guests are bused from Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation to be immersed in the past, present and future of American manufacturing as they get an inside look at where the Ford F-150 is assembled.

Since 2004, the Ford Rouge Factory Tour has welcomed more than 2 million guests from all over the world.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2024 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Masterpiece of Motion

Our carousel exposed: a simple mechanism with lots of pizzazz

Each week Jacob Hildebrandt, manager, historic operating machinery, climbs atop Greenfield Village's Herschell-Spillman Carousel to properly lubricate its gears and fittings. During the season, the Henry Ford staff also do daily safety inspections of the carousel, listening for squeaks and grinding noises, inspecting for loose boards and bolts, putting pressure on every animal and many other checks. / Photo by EE Berger

In this blog, we examine what's at the heart of the carousel — the inner workings that keep the ride in motion and the staff that maintains its motor, gears and bearings so thousands of visitors can go round and round and up and down each year.

Today, a 10-horsepower electric motor runs the carousel. In 1913 when the ride was built, it was likely run by an early Westinghouse electric motor, said Jacob Hildebrandt, manager, historic operating machinery.

A fairly simple machine, the carousel's motor turns a vertical drive shaft that runs up to the crown of the ride. The rotation of that shaft then rotates a large ring gear at the top that turns the carousel round.

“It's like twirling an umbrella,” said Hildebrandt. “All the power comes from the middle and spreads out.”

The carousel's electric motor is connected to a gearbox with an electric brake and torque converter similar to a vehicle so the motor can run before the carousel begins to spin, avoiding jerky, sudden movements. The brake can bring the ride to a complete stop within two revolutions.

Radiating from the middle are smaller crankshafts with bevel gears, which is what the carousel's moving animals hang from. The rotation of these shafts and gears — and therefore the up-and-down motion of the animals — is powered by the carousel's spin.

Marc Greuther, vice president, historical resources and chief curator, who has intimate knowledge of the underbelly of the carousel, likens the transfer of power from a shaft on a vertical axis to a set of undulating animals on a platform as “a quiet masterpiece of motion."

To keep this masterpiece in motion, Hildebrandt, one other full-time employee and a part-time staffer are on-site daily climbing about the ride lubricating its gears and fittings. “Functionally, the grease we use is one of the most modern things about the carousel today,” he said.

The carousel is equipped with highly durable Babbitt-style bearings, added Hildebrandt, rather than the now more common ball bearings. In the early days, these bearings and the carousel's gears would have been lubricated with a less-viscous oil, which is much messier and ephemeral than the grease now used — which “sticks to everything,” said Hildebrandt.

While some of the carousel's larger gears have worn and been replaced over the years, for the most part its internal hardware remains original. “It's a fairly straightforward mechanism underneath the skin,” said Greuther. “An application of very, very practical machinery that's the result of innovation and applications in industry.”

Jennifer Laforce, managing editor, The Henry Ford Magazine