Old Enough to Vote

| Written by | Andy Stupperich |

|---|---|

| Published | 7/1/2021 |

Old Enough to Vote

| Written by | Andy Stupperich |

|---|---|

| Published | 7/1/2021 |

| The 26th Amendment The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age. |

In 1971, the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. The U.S. Congress passed the legislation in March and sent it to the states. In less than four months, the requisite number of states had ratified it—the fastest ratification of any amendment to the Constitution.

Though this constitutional victory may seem relatively quick, it wasn't. The idea of lowering the voting age to 18 had been an almost perennial topic in Congress since World War II, nearly 30 years before the 26th Amendment's ratification. Only in the 1960s, with the confluence of the civil rights struggle, American involvement in the Vietnam War, and the coming of age of the baby boom generation, would lowering the voting age finally become a reality.

Old Enough to Fight, Old Enough to Vote

In 1942, the U.S. Congress amended the Selective Training and Service Act, lowering the military draft age to 18. With passage of this revision, several members of Congress also proposed lowering the voting age. They argued that if 18-year-old Americans could fight and die for their country, they should also be given the right to vote. Though nothing came of the proposal in Congress, numerous states debated the issue. In 1943, Georgia became the first state to lower the voting age, but no other states followed.

Ford Motor Company employees line up to register for the draft, April 1942. Soon after America declared war in 1941, Congress required all American men 18 to 64 years old to register for the draft—though men 18 and 19 years old were not liable for military service. That changed when Congress lowered the draft age to 18 in 1942. / THF624578

The debate continued after the war, though it was largely unsuccessful. In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower advocated for the measure in his State of the Union speech, but little action came from his plea. Kentucky did lower its voting age to 18; Alaska and Hawaii, upon entering the union, established voting ages at 19 and 20, respectively. But again, the movement stalled, and no other states expanded the franchise to those 18 years to 21 years old.

The push to lower the voting age, however, gained momentum in the 1960s. Many in the baby boom generation—those born after the end of World War II and now of draft age—began to protest and voice their opposition to some of the country's social, political, and military policies.

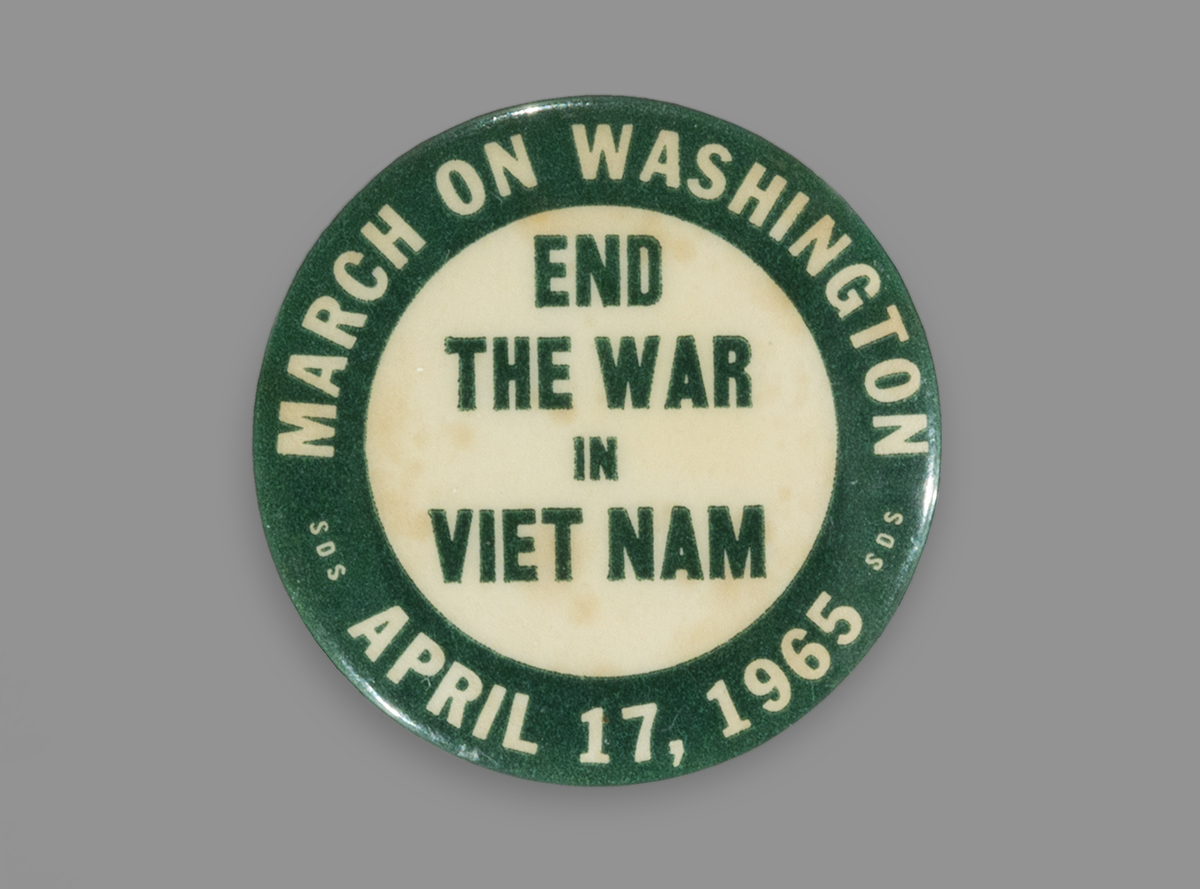

THF166830

This activism countered the prevailing argument that 18-year-olds were not mature enough to vote. Proponents also noted that America's educational system had more than prepared young Americans to enter the political sphere at 18. More importantly, supporters cited the inequity of many draft-age Americans being sent to fight in Vietnam who were unable to vote. Young Americans latched onto the phrase "Old Enough to Fight, Old Enough to Vote"—a popular slogan used during World War II. Songwriters also incorporated these injustices into the lyrics of protest songs.

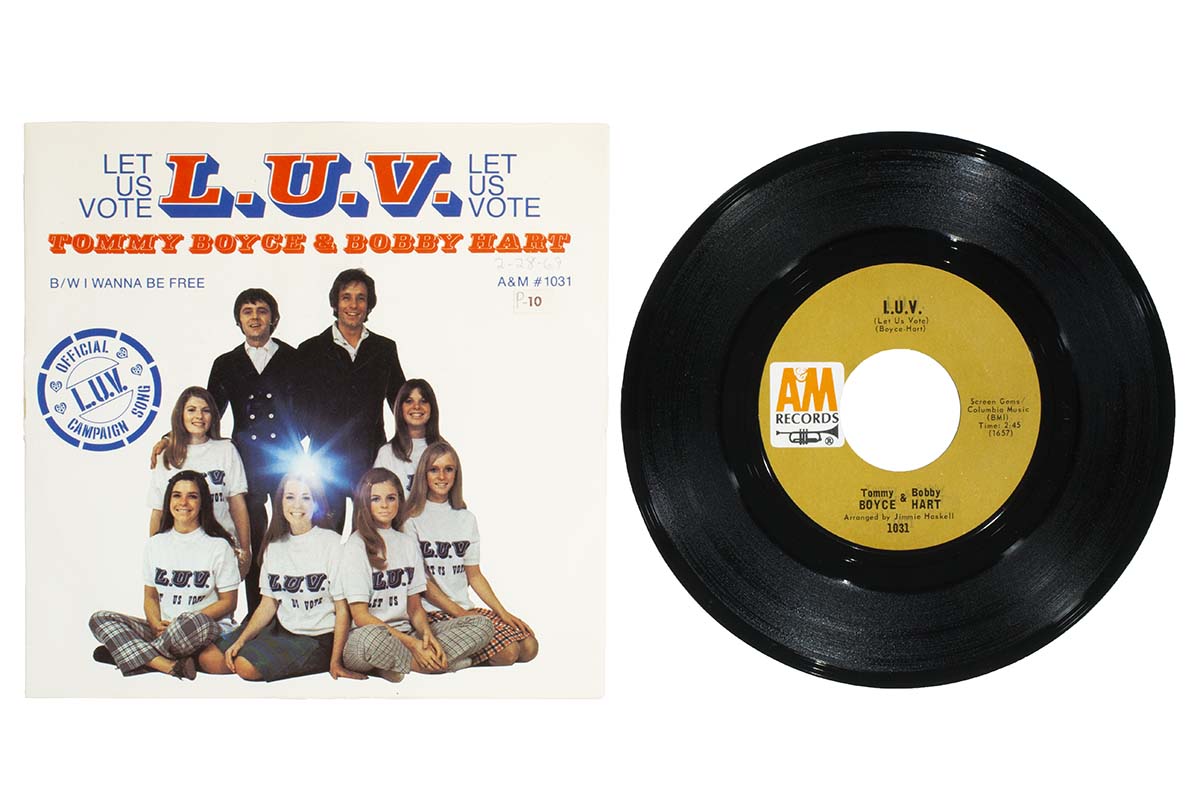

Let Us Vote (L.U.V.)

THF185716

By the late 1960s, youth and student-led organizations lobbied for an extension of voting rights. These grassroots groups found support from influential politicians, celebrities, veteran groups, and larger national organizations. In late 1968, the "Let Us Vote" (L.U.V.) campaign, headquartered at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, gained national recognition when its leader appeared on The Joey Bishop Show. The group expanded, and by March 1969, L.U.V. claimed to have chapters on 200 college campuses and in 1,500 high schools throughout the country. More recognition followed when the singer-songwriter duo "Tommy" Boyce and Bobby Hart (famed for writing songs for The Monkees) composed the song "L.U.V. (Let Us Vote)" in late 1969. The work became the official song for the L.U.V. campaign.

Voting Rights Act and the 26th Amendment

While America's youth continued to demand the vote, key congressional leaders passed legislation to make it a reality. In the spring of 1970, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 came up for reauthorization. Senators Edward Kennedy, Warren Magnuson, and Majority Leader Mike Mansfield added a proposal to the reauthorization bill that would lower the voting age in all elections (local, state, and national). The Senate passed the bill and sent it to the House. There, members of the House faced a quandary. Some representatives believed Congress did not have the authority to lower the voting age but were concerned that by not passing the bill they would endanger the extension of the Voting Rights Act. Fearing to risk the loss of the landmark civil rights legislation, House members passed the bill with scattered dissent. President Richard M. Nixon, who supported lowering the voting age but was also uncomfortable with making the change through congressional decree, nevertheless signed the reauthorization.

It appeared a constitutional amendment was unnecessary. However, a court challenge to the section of the Voting Right Act lowering the voting age (something urged by President Nixon and others) put an amendment back into the mix. In the fall of 1970, Supreme Court justices ruled by a narrow margin that Congress did have the right to lower the voting age, but only for federal elections—Congress could not mandate it for state or local elections. States now faced an administrative nightmare. If state legislatures could not change their constitutions before the 1972 presidential election, they would need two voting lists—one including voters 18 to 21 years old for federal elections, and another excluding those voters for state and local elections. Two voting lists would also have an unwelcome economic impact. State elections officials would need to purchase new or additional voting equipment to deal with this logistical problem. Something needed to be done.

The solution became the 26th Amendment. In March 1971, Congress quickly passed the amendment and sent it to the states. Less than four months later, by July 1, the requisite 38 states had ratified it—the fastest ratification of any amendment to the Constitution. On July 5, 1971, in a White House signing ceremony, the 26th Amendment was certified. An estimated eleven million new voters were added to the rolls, ensuring their voices would be heard when they showed up at the polls.

Andy Stupperich is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Themes |