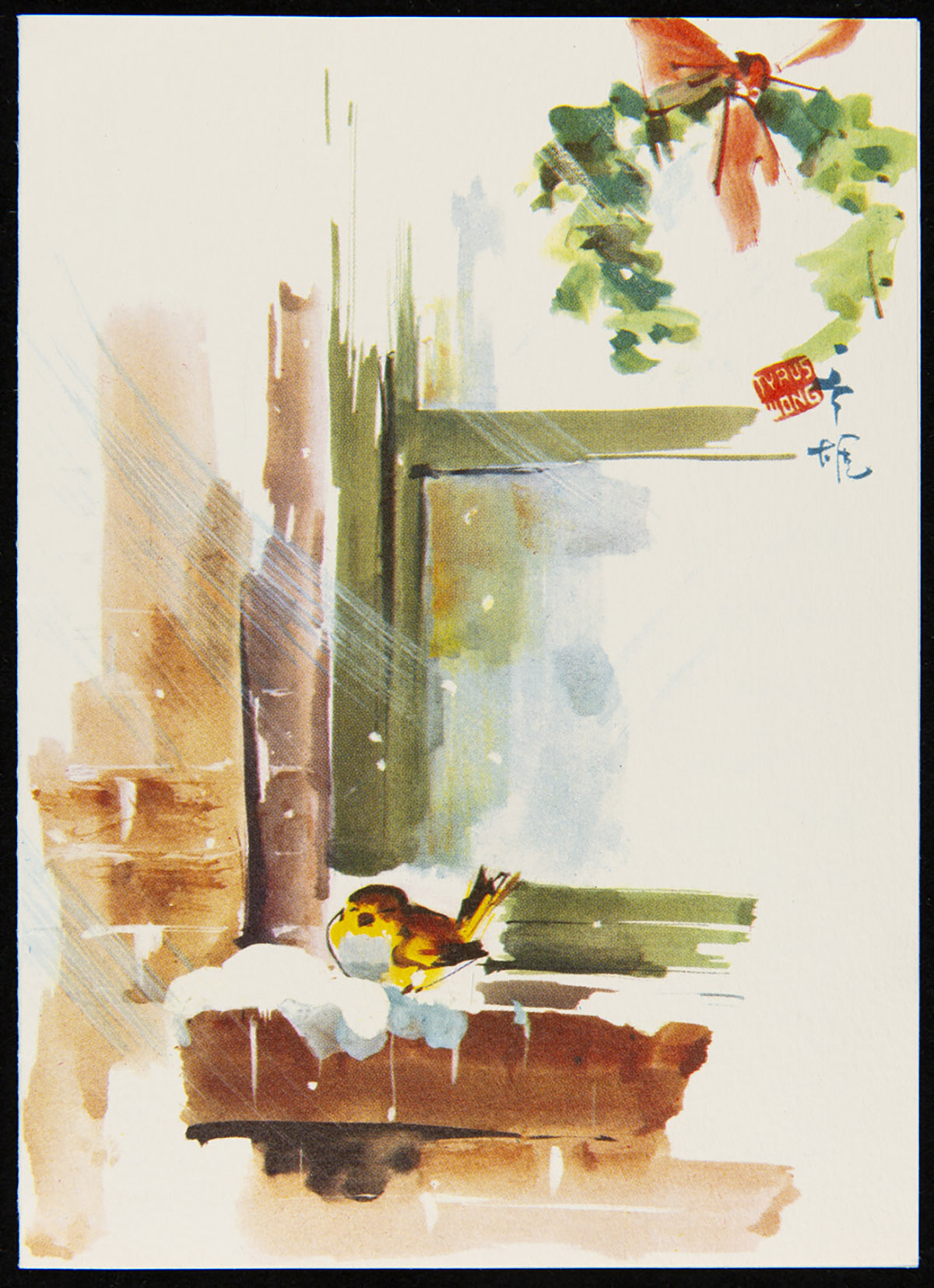

Illustrating the Holidays: Christmas Cards by Tyrus Wong

Americans love to send — and receive — Christmas cards. Since the late 1800s, Christmas card production has grown, aided by inexpensive printing technologies and a prosperous — and increasingly mobile — American population. After the Second World War, greeting card companies looked for ways to outshine their competitors. Some companies commissioned production artists, animators, and illustrators who worked for West Coast film studios to create Christmas cards that appealed to mid-century Americans' tastes. Tyrus Wong, who worked for Disney and Warner Brothers Studios, is considered one of the finest Christmas card artists from the 1950s, '60s and '70s.

"Snow Bird," designed by Tyrus Wong for California Artists, 1955. / THF624835

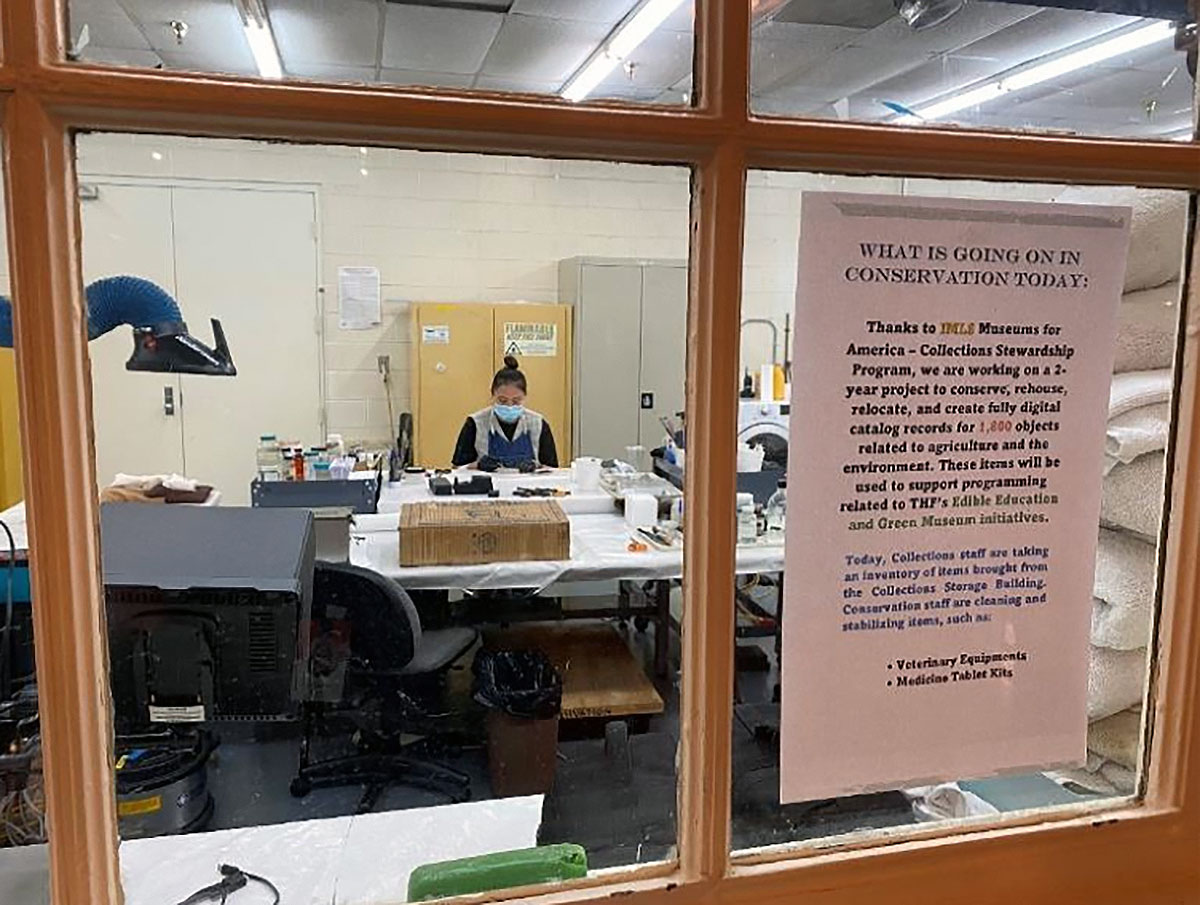

Continue ReadingSecond Quarter IMLS Grant Update for 2023

To celebrate the completion of another six months of work on our 2022-2024 IMLS Museums for America – Collections Stewardship Program, the Conservation staff are showcasing some standout objects we have conserved. We are now on the second year of a two-year project to conserve, rehouse, relocate and create fully digital catalog records for 1,800 objects related to agriculture and the environment that have resided in the Collections Storage Building. Many of these objects will be used to support our Edible Education and Green Museum initiatives.

Stop by the back of the museum, near the steam engines, to get a peek through the windows of the Conservation lab and see what staff are currently conserving.

This decorative milk pail from the Gwinn Dairy Collection had layers of dirt and debris on the surface to be removed. What was found on the underside was quite a surprise.

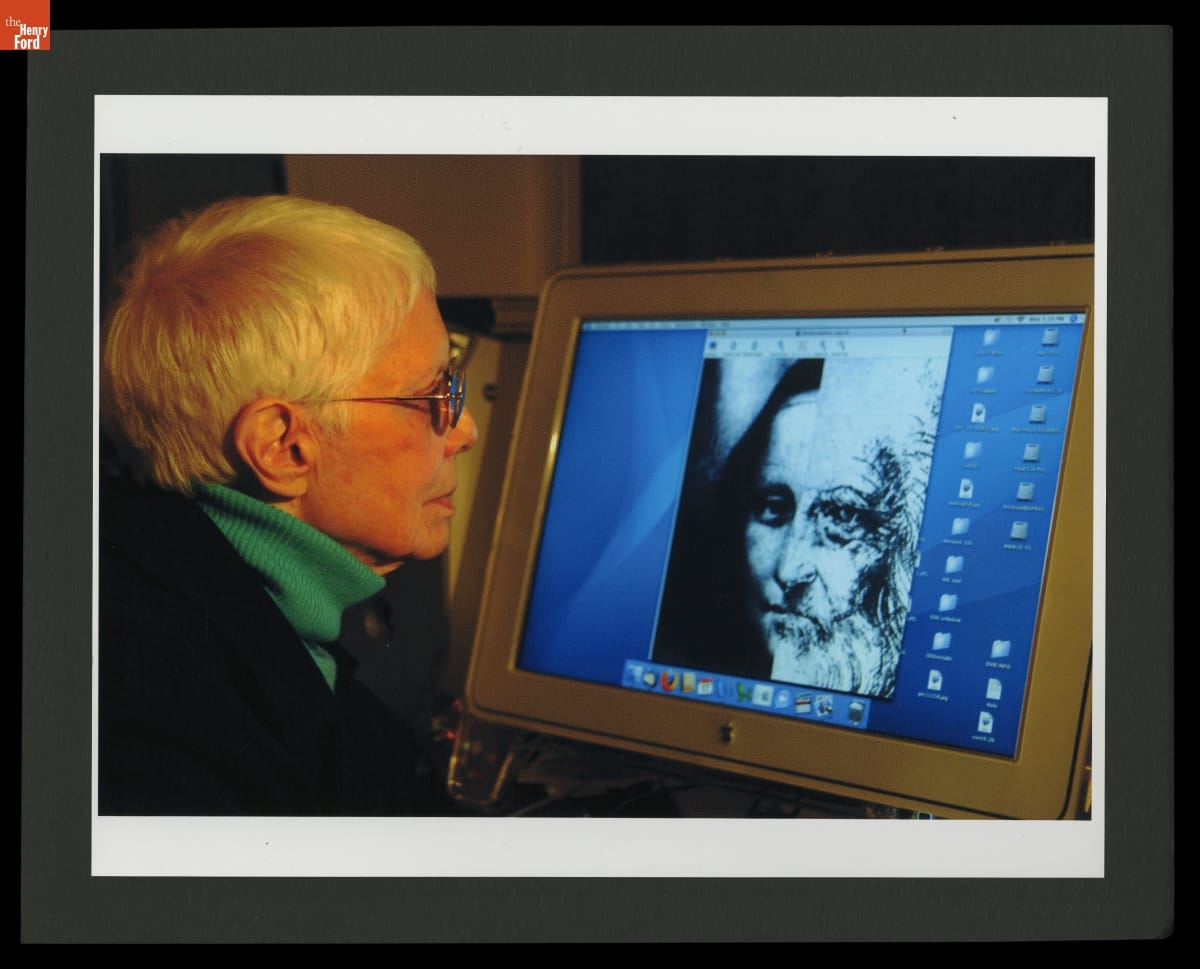

Continue Reading“Creating in my head”: How Lillian Schwartz turned Life’s Obstacles into Opportunities

Lillian Schwartz working at her home computer circa 2010. / THF706855

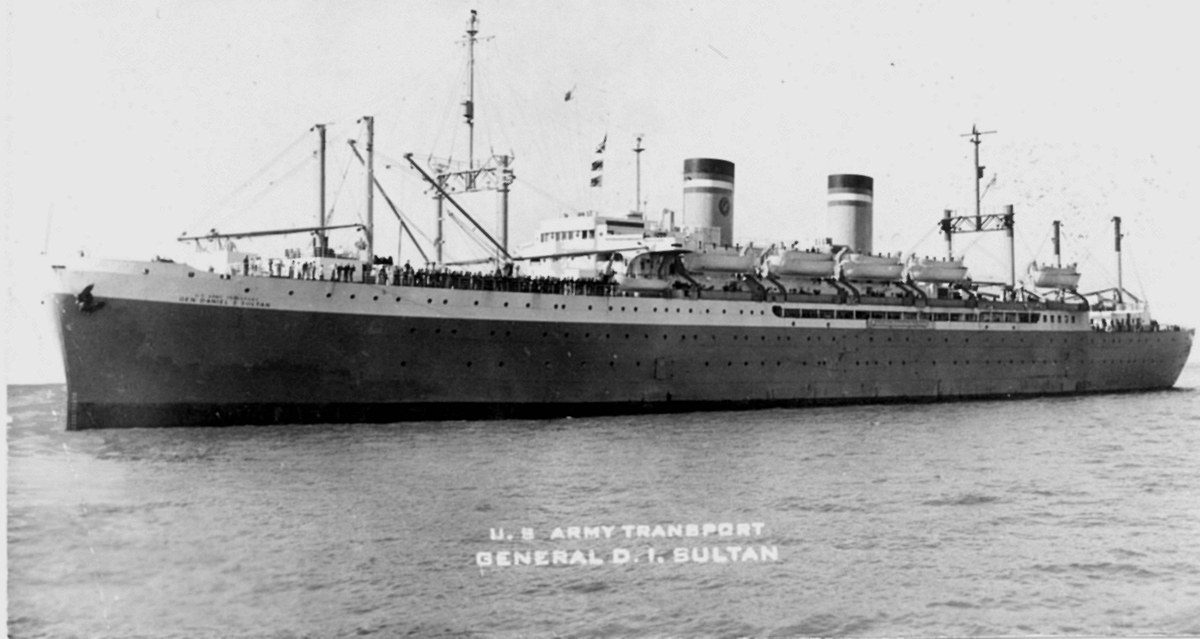

In 1949, Lillian Schwartz — an artist who became well known for her experimental spirit — packed her bags and boarded the U.S. Army transport ship General Daniel I. Sultan. Lillian's husband, Jack Schwartz, was a doctor and military service member. Several months earlier, he took up a new station in a pediatric hospital far from his home in New Jersey — in Fukuoka, Japan. Lillian and her young son now made the lengthy trek to join him there. Ten days of worry about seasickness, dysentery and their safety aboard a military vessel passed as they crossed the Pacific Ocean.

U.S. Army transport ship General Daniel I. Sultan. Lillian sailed on this ship to join her husband, Jack, in Japan in 1949. / THF611239

Continue ReadingEdison Homestead Holiday Nights Recipes, c. 1915

The holiday season is upon us, and visitors to Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village may catch an Edwardian Christmas dinner being prepared by presenters at the Edison Homestead. Try our delicious holiday recipes at home!

Christmas treats laid out for guests to see during Holiday Nights at the Edison Homestead. / THF Photography, 2015.

For families in the 1910s, domestic life was changing rapidly as home economics and industry shaped how women viewed household chores and food preparation. The publications housewives turned to for holiday entertaining ideas also gave them plenty of ideas on how to spend money. Some guides were published by manufacturers looking to advertise all the uses for their products, like the Dennison Party Books or the Jell-O and the Kewpies Cookbook. Women’s magazines of the era featured gift guides and special Christmas advertisements advising readers on both the perfect gifts for the people on their lists and the perfect Christmas dinner menu. Middle-class homemakers used improved household technology, new consumer products, and helpful domestic guidebooks to celebrate Christmas traditions that are still recognizable 100 years later.

Hallmark’s Christmas Classics

The Christmas season brings cherished traditions and much-anticipated activities. These Hallmark ornaments reflect some of these classic Christmas experiences.

Friendly Greetings, 1992 / THF350088

Sending Christmas greetings is a long-standing custom — whether through a physical or digital greeting card or social media. Though the postman may deliver cards to our mailbox, or greetings may arrive through email or social media, holiday missives are one way of letting family and friends know we are thinking of them and wishing them well at this festive time of the year.

Born to Shop, 2004 / THF354780

Continue ReadingSymbols in Simplicity: The Photography of Margaret Bourke-White

Photojournalism at its best has the power to extend beyond being merely documentary; at its finest, it is intended to make the viewer think or feel something about the subject matter. In the early part of the 20th century, photojournalism saw a new boom, and the field was led by innovative photographers — many of them women — with opinions about the subjects they shot. Among these pioneers was Margaret Bourke-White.

Margaret Bourke-White was born on June 14, 1904, in New York City. Her father, Joseph White, was a factory superintendent and inventor with a mind for machinery; her mother, Minnie Bourke, was a homemaker who firmly believed that Margaret should not be impacted by traditional gender limitations. From a young age, Margaret shared her father's interest in the mechanical, while also longing for a career that would offer adventure and excitement. In 1924, she married photographer Everett Chapman, but the marriage dissolved in 1926. After graduating from Cornell University in 1927, she moved to Cleveland to pursue a career in commercial photography.

Continue ReadingThe Politics of a Press

During the 1920s, Henry Ford’s rampant collecting of Americana, which would become the basis of his museum’s collection, led him (through his purchasing associates and collectors) to pursue artifacts with compelling provenances attached to some of America's most fabled figures. While Ford maintained an interest in items of the “everyday” American, his avid pursuit of artifacts related to traditional American folk heroes, like George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, aligned with the interests of other collectors of the time. It should be no surprise, then, that when Ford learned about a printing press purportedly used by celebrated writer and humorist Samuel Clemens, otherwise known as Mark Twain, he leveraged his national network to acquire it.

Washington press, circa 1848, decorated with reliefs of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. / THF101402

Continue Reading“An oil painting by Matisse of a humanoid robot playing chess.” “An astronaut riding a horse in photorealistic style.” “An armchair in the shape of an avocado.” These are only a few input suggestions for the image generation platform known as Dall-E 2. In 2021, the company OpenAI launched the first iteration of Dall-E, and it quickly took the internet by storm. The program relies on a combination of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence — or AI — to produce unique images from natural language text prompts.

But how unique are these images? Programmers, scholars and news anchors alike wrestled with this question in late 2022. The long-term consequences of technologies like Dall-E — including the chatbot ChatGPT — are still evolving. Some people see AI as a helpful aid for professional and personal creativity; others decry it as the end of art-making as we know it.

Like OpenAI's prompts suggest, Dall-E can mimic the style of other artists. Many artists' images, while visible on the internet, do not belong to the public domain. But Dall-E still mines their work to produce its own works. Is this fair practice? Is Dall-E stealing, or is it learning, like an apprentice learns from a master? Is Dall-E itself an artist?

Continue ReadingWhose Land Are You On?

The Paris of the Midwest. That was the phrase used to describe Detroit in the late 19th century. It was a city designed with a mission, and that mission was to impress, which it did. But the city and the land surrounding it were home to thousands of Indigenous peoples who, more often than not, are left out of the story.

Point of origin marker in Detroit. / Photo courtesy of author.

History says that Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit on July 24, 1701. But before that, several Indigenous nations were living on the land, called Waawiiyaataanong, meaning “where the river bends.” The Potawatomi, Odawa, Ojibwe, Miami and Huron all called this area home. As with colonization, though, these nations had to leave the site as European settlements began to spread.

When the fort and the city were being built, the Indigenous peoples in the area were encouraged to settle around the fort. In Cadillac’s mind, this added another layer of protection, not just for the fort but also for the fur trade. With its location on a waterway now called the Detroit River, Detroit was an important center for fur trading. The river linked Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie, both important in trade. As the settlement grew, the tides changed, and the Indigenous folks who called the area home soon found their lives turned upside down.

Continue ReadingCranberries & Environmentalism at The Henry Ford

The Great Cranberry Scare

On November 9, 1959, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Arthur Flemming announced to the American public that a cranberry crop from the Pacific Northwest had tested positive for a herbicide. Growers began using aminotriazole to eliminate deep-rooted grasses and sedges from cranberry bogs in the mid-1950s, but the weed killer proved to cause thyroid tumors in test animals and left a residue in some cranberries. Even the Eisenhowers in the White House replaced cranberry sauce with applesauce at their 1959 Thanksgiving dinner.

Documenting this dangerous herbicide residue triggered the “Great Cranberry Scare” of 1959. The media coverage that resulted marked a turning point in modern American food scares and helped launch the modern environmental movement. Environmentalist Rachel Carson incorporated these events into her pathbreaking book, Silent Spring (1962).

This incident reminds us of the important efforts of one of our collecting initiatives at The Henry Ford: the environment. The Henry Ford received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to increase physical and intellectual control of agricultural and environmental artifacts. Cranberry harvesting tools, including rakes and bog shoes for horses hauling produce from bog to processing facility, count among the artifacts made more accessible because of IMLS funding.

Continue Reading