Strawberries

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 6/11/2021 |

Strawberries

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 6/11/2021 |

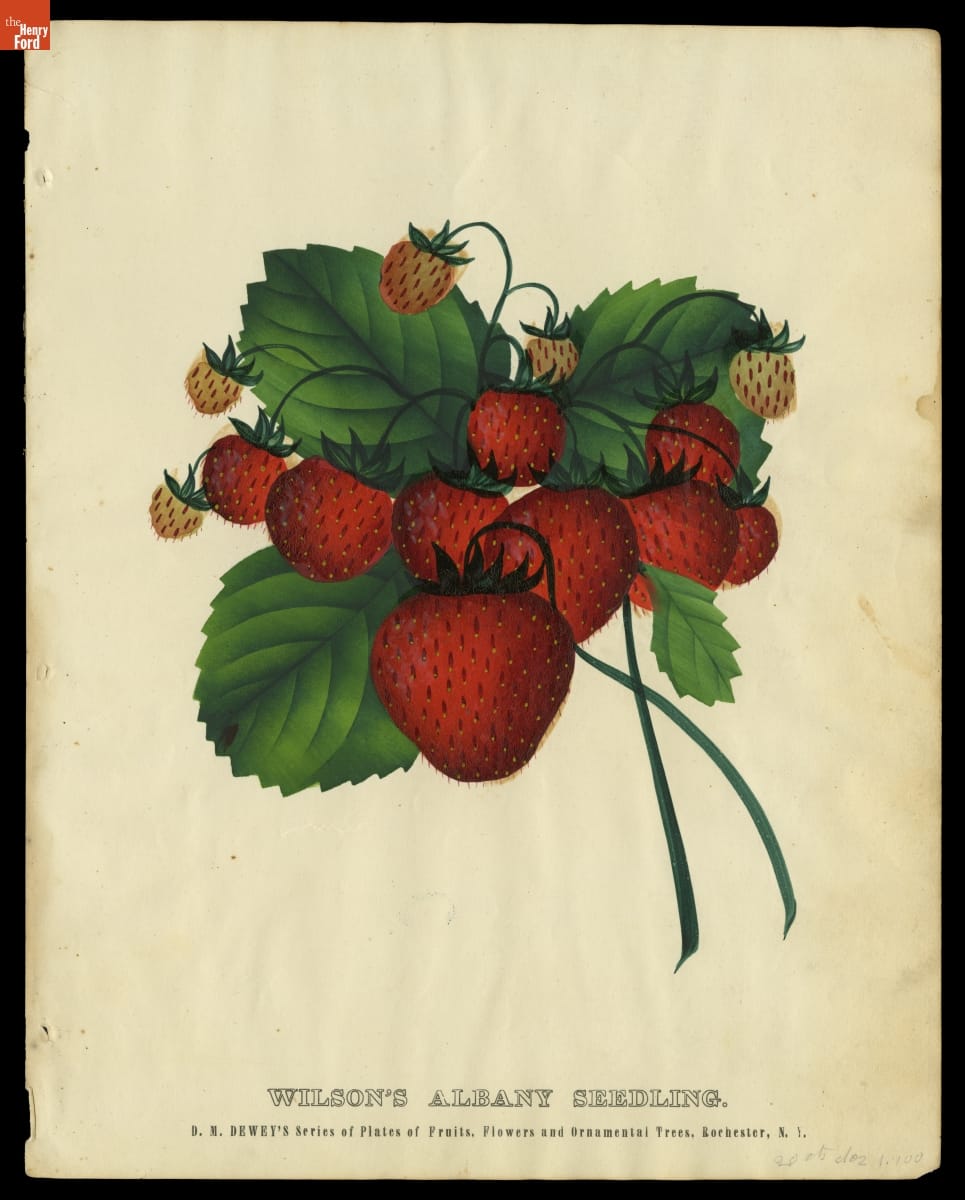

“Wilson’s Albany Seedling” from D.M. Dewey’s Series of Plates of Fruits, Flowers and Ornamental Trees, 1871-1888. The Chicago Tribune (July 4, 1862) gave a shout-out to Wilson’s Seedling in “A Chapter on Strawberries: How to Eat Them. Features of the Strawberry Market.” / THF148036

We wait patiently for the first field-ripened strawberry of the season. But horticulturalists have tried to reduce this wait-time for decades by selecting strawberry plants that yielded fruit earlier—and fruit that grew bigger, tasted better, and matured to a brilliant scarlet-red color. They planted seeds from these plants, and after consistent yields across generations, then advertised the improved cultivars for sale. Farm families, market gardeners, and horticulturalists purchased, planted, and harvested these plants, and repeated this, season after season.

The first volume of the Michigan Farmer and Western Agriculturalist in 1843 reported on the latest innovations. Editor Daniel D. T. Moore waxed eloquent about “Strawberries -- Large and Luscious!” He described a Michigan-grown fruit as “the largest and most delicious strawberries we have ever before seen or tasted” (July 1, 1843, pg. 76).

That “Large and Luscious” berry had no name. Moore described it as “a native of this State, cultivated.” Subsequent issues of Michigan Farmer, however, specified numerous varieties and their merits. John Burr in Columbus, Ohio, listed six different seedling strawberries for sale in August 1847, just in time for transplanting. He stressed the large uniform size and sweet flavor of the Ohio Mammoth berry as well as its hardiness. He described a namesake, Burr’s New Pine, as maturing “very early” with a “highly aromatic, sweet and delicious flavor,” concluding that it was “unquestionably the very best strawberry cultivated.” He sold these two seedlings for $2.50 per dozen, while he sold his stalwart, Burr’s Old Seedling, for 50 cents per dozen or $2.00 for 100 (August 23, 1847, pg. 96).

Horticulturalists generated plants suitable to local climates and useful to local market gardeners. The go-to early berry in one place might not transfer well to another growing zone. Sometimes hype did not match performance. James Dougall, a nurseryman living across the Detroit River, south of Windsor, Ontario, Canada, assessed 15 varieties of strawberries for Michigan Farmer subscribers in 1849. He described the Duke of Kent’s Scarlet as “Only valuable as being the earliest strawberry, but not worthy of cultivation in comparison with the large early scarlet which is double the size, and ripens only a few days later” (August 1, 1849).

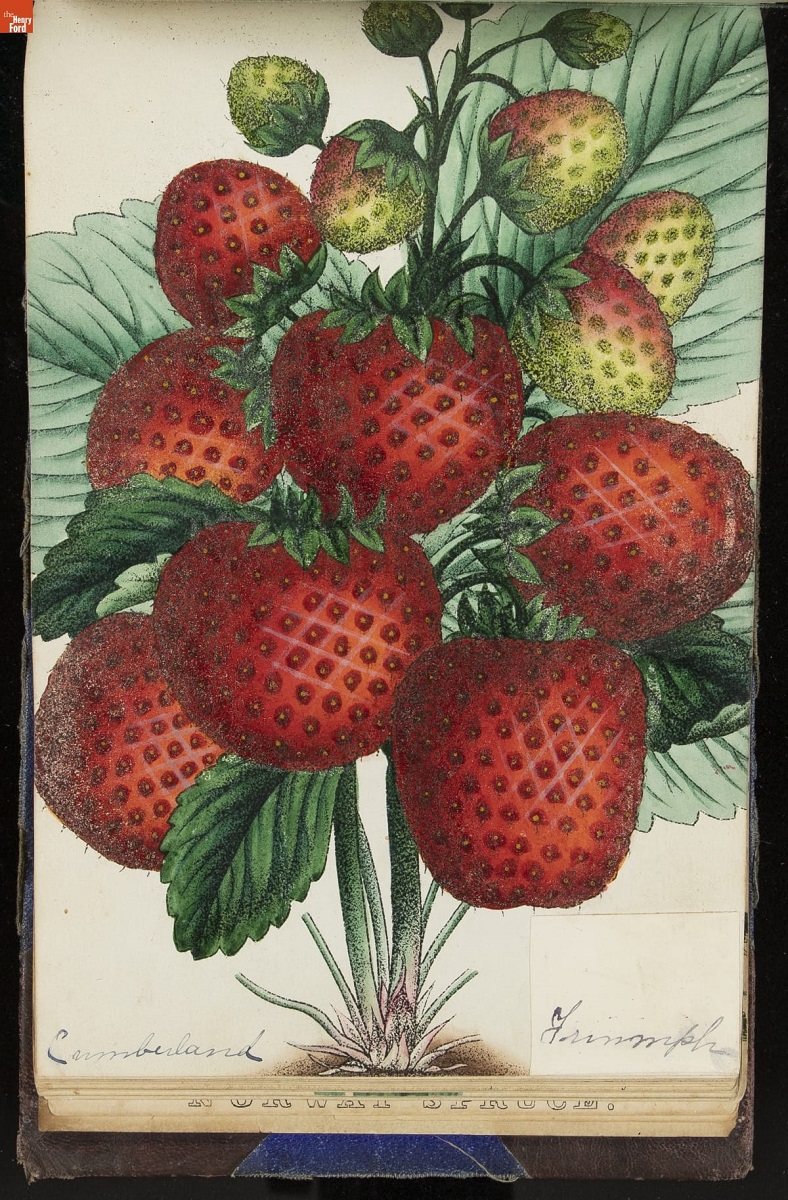

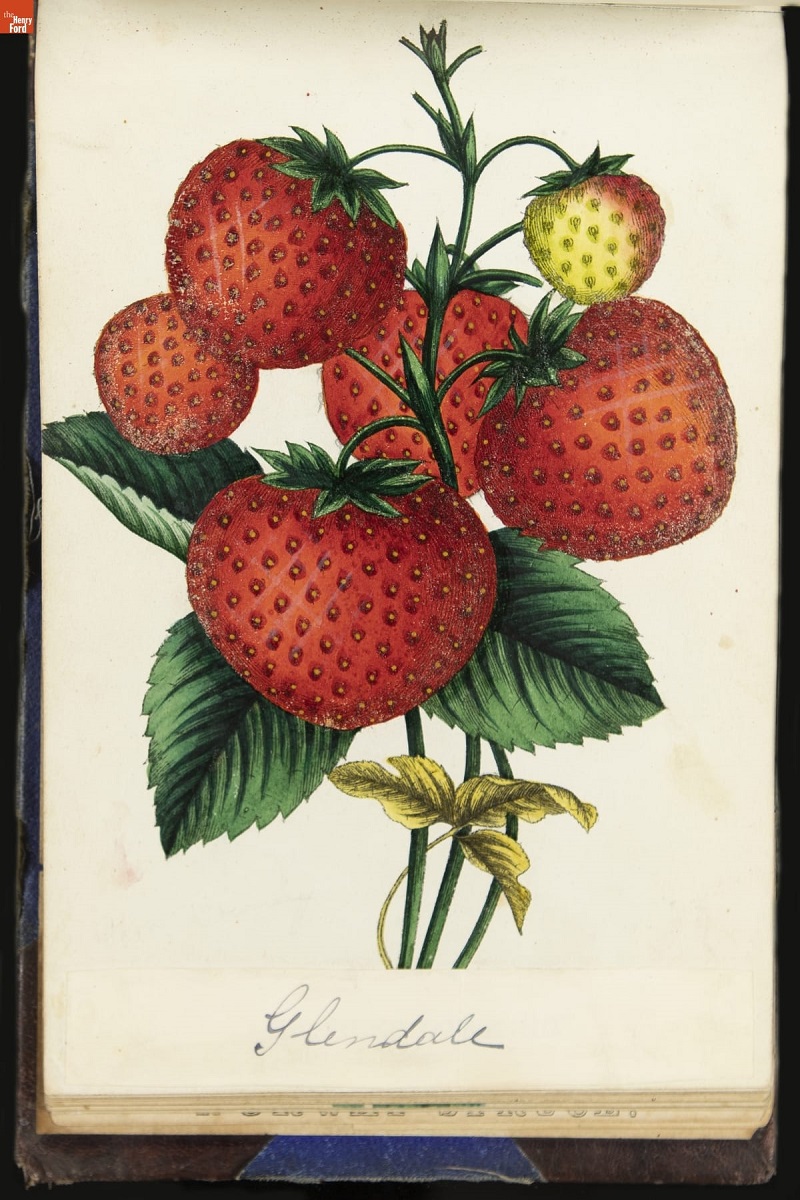

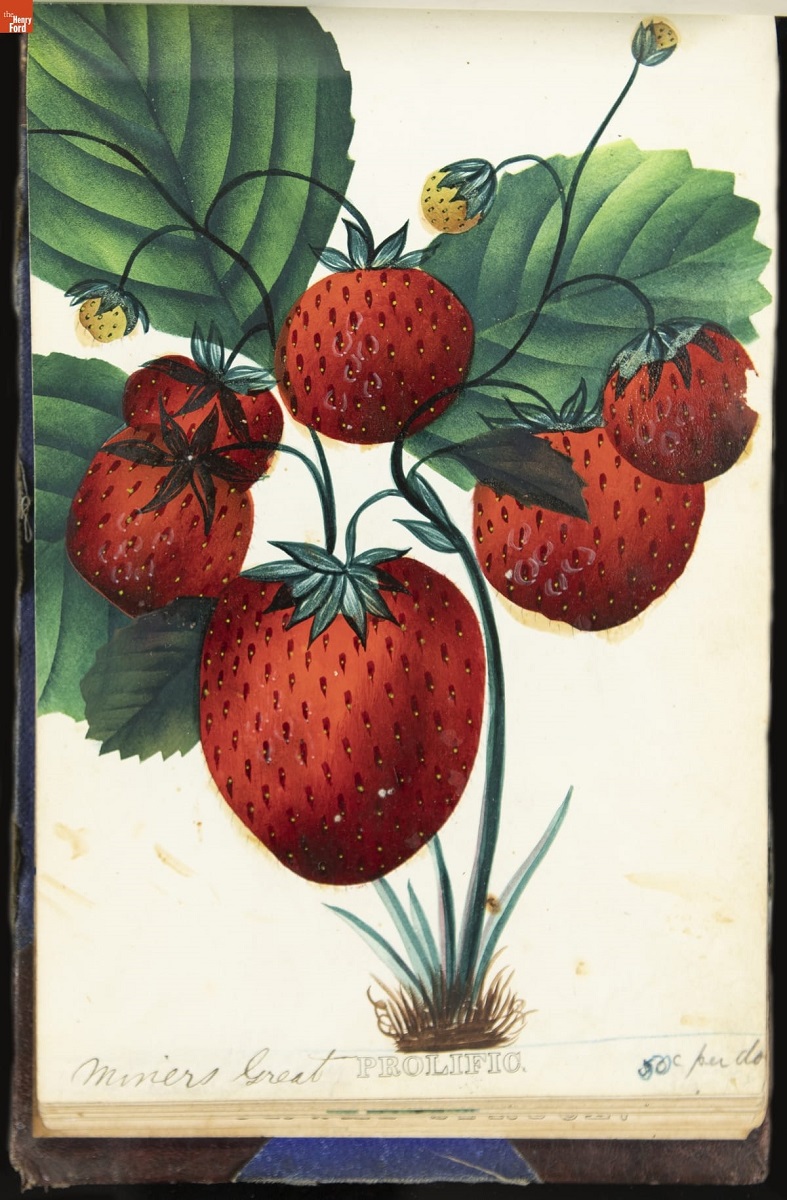

The public remained eager for the seasonal treat. “And what fruit is more delicious than the strawberry?” wondered Michigan Farmer editor Warren Isham in May 1850. But propagating strawberries required regular replanting, at least every two or three years, to maintain the patch. This sustained a lucrative business for plant breeders and horticulturalists. Colorful illustrations helped them capture the attention of growers, as the illustrations below from horticultural sales books indicate.

Nurseryman’s Specimen Book, 1871-1888, page 58. The Illustrated Strawberry Culturist (1887) described the Cumberland Triumph as “jumbo . . . light bright scarlet. . . flesh pale pink of excellent flavor. Very popular among amateur cultivators of the Strawberry” (page 48). / THF620221

Nurseryman’s Specimen Book, 1871-1888, page 57. The Illustrated Strawberry Culturist (1887) described the Glendale as “large . . . dull scarlet. . . not first quality, but a valuable late variety for market” (page 49). / THF620220

Nurseryman’s Specimen Book, 1871-1888, page 56: Miner’s Great Prolific, advertised for 50 cents per dozen. The Illustrated Strawberry Culturist (1887) described the Miner’s Great Prolific as “large to very large. . . deep bright crimson. . . vigorous” and “a popular variety among amateurs as well as those who cultivate Strawberries extensively for market” (page 51). / THF620219

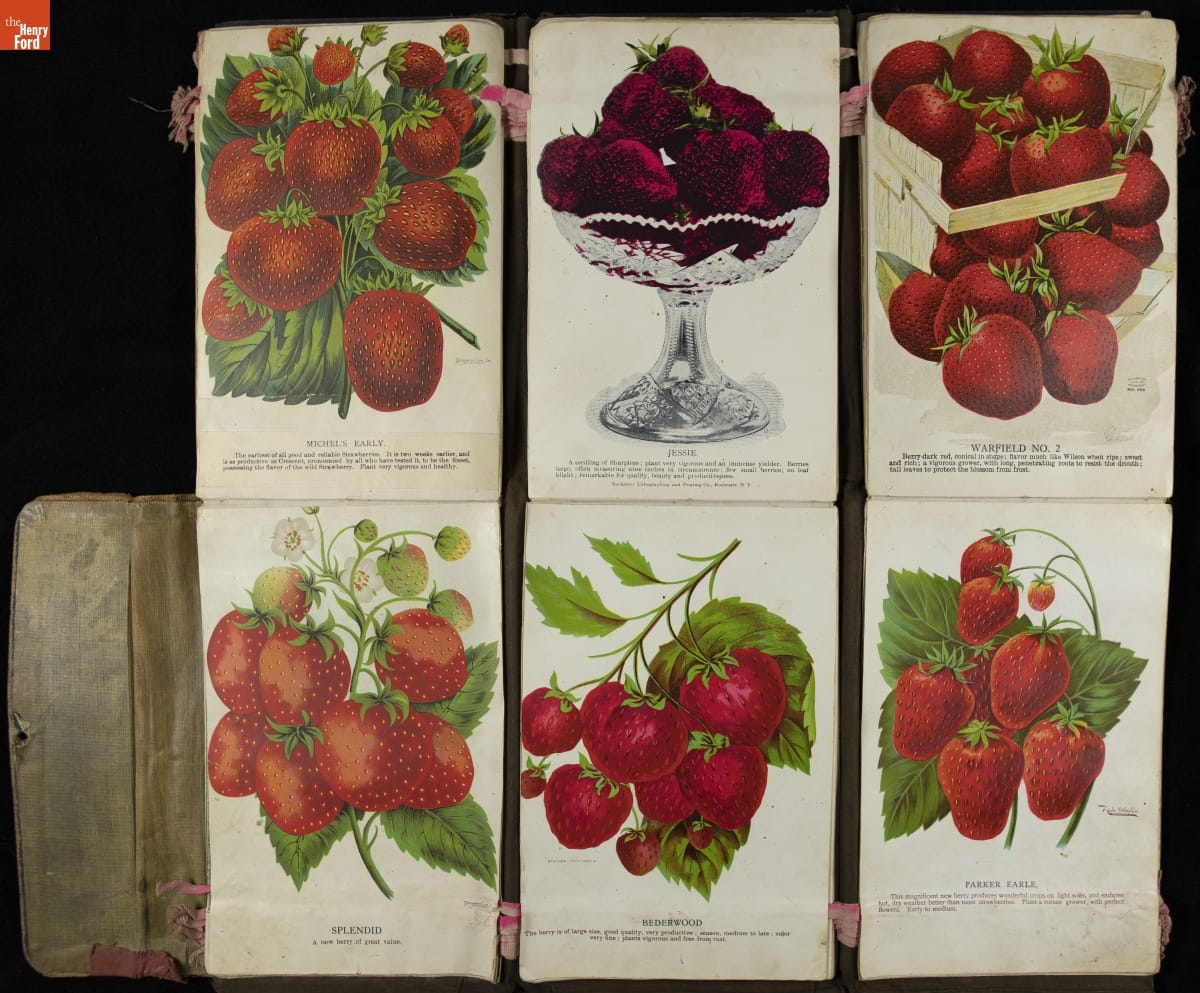

Nurseryman’s Specimen Book, Great Northern Nursery Co., Baraboo, Wisconsin, circa 1900. This specimen book, carried by a salesman, included cloth pages that folded out. Customers could then compare attributes of six berries including: Michel’s Early, Jesse, Warfield No. 2, Splendid, Bederwood, and Parker Earle. / THF620262

As strawberries ripened, growers had to get busy picking and processing the perishable fruit. For farm families, this often meant that all members took their turn picking in their own patches. Families without a strawberry patch, but with a yearning to pick their own, could do so at community gardens or pick-your-own nursery businesses.

Ella and Edward Posorek in a Strawberry Field, circa 1932. / THF251170

Growers raising large quantities for market relied on agricultural laborers hired to pick as fast as berries ripened. Two photographs indicate the scale of production on the Atlantic coast, serving Eastern urban markets, and in California, serving Western fresh markets and processor demand.

Picking Strawberries, Charleston, S.C., 1907. This photograph, part of the Detroit Publishing Company Collection, shows the scale of Southern strawberry fields that helped satisfy customer demand in urban coastal markets. / THF624649

Japanese Men and Women in the Strawberry Fields, California, 1921-1922. (Note that while this photograph features berry cultivation, it was taken to support an article in the Dearborn Independent attacking Japanese farmers' real status in the fruit-growing industry in California. More information on the photo can be found in our Digital Collections at the link that follows.) / THF624653

Educational materials designed for geography instruction often featured fruits and vegetables. This Keystone View Company stereograph, in tandem with an instructional workbook, oriented teachers to lessons that helped students understand sources of their food supply. In the case of strawberries, students could see a person about their age busy in a strawberry field in Florida, picking a crop that the students might eat on their strawberry shortcake!

Picking Strawberries in January in Florida, circa 1928. / THF624669

Fresh berries had to be eaten quickly to enjoy them in all their lusciousness. The Chicago Tribune drew readers’ attention to the “luxury” of strawberry shortcake at the height of berry season in that Northern city (July 14, 1857): “Make a large, thick shortcake, split it twice through, and spread with butter and fresh strawberries and sugar, put the parts together again, and serve hot.”

The Chicago Tribune shared two additional recipes in a “how to eat them” feature a few years later (July 4, 1862). The editor recommended starting with a recipe for a very light soda biscuit, baked in a round tin about the size of a dinner plate. Directions continued with instructions to immediately split the baked cake in two or three parts. “Butter each part slightly—spread a thick layer of berries upon one of the slices, then place the other slice over it. . . . Scatter powdered sugar over the berries as they are placed on the slices, and finish by pouring a goodly portion of thick, rich cream upon the berries before the next slice is laid on.”

One last recipe comes from “About Strawberries,” printed in the Detroit Post & Tribune and republished in the True Republican (Sycamore, Illinois). This described the common strawberry shortcake as “a favorite [but] rich” dish. The editor suggested taking “one quart of flour, three tablespoonfuls of butter, one large cup sour cream or rich loppered milk, one egg, one tablespoonful white sugar, one tablespoonful soda dissolved in hot water, and one saltspoonful salt. Rub the salt, butter and flour together; add the soda to the sour milk; stir in the egg and sugar with the milk; put all together, mixing quite soft. Roll lightly and quickly into two sheets, the one intended for the upper crust fully half an inch thick, the lower less than this. Now lay one sheet of paste smoothly upon the other and bake until done. While warm, separate the sheets just where they were joined and lay upon the lower or thick sheet a thick, deep coating of strawberries; then add a coat of powdered sugar and cover with the upper crust . . . serve at tea, cut into triangles and cover with sweet cream and with sugar sprinkled over it. Always send around the powdered sugar and let the guests help themselves” (June 29, 1878).

Readers knew that they could only eat so much shortcake. Yields always outpaced demand. To meet the need, newspaper editors encouraged readers to turn the fruit into jam or preserves before the berries spoiled. Food processors also approached fruit preservation on an industrial scale. The postcard below from the H.J. Heinz Company provides a behind-the-scenes view of women in their work uniforms stemming strawberries as part of the preserve-making process.

Centennial Post Cards 1869-1969. H.J. Heinz Company, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania / THF291994

Strawberries remain one of the most highly anticipated seasonal fruits. Few compare in taste sensation. In the past as now, however, market opportunities lead growers to pick berries before they ripen to prevent damage in transit. Today, the end of strawberry season in one location means the end of the taste sensation, but not the end of availability for consumers.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, for editorial advice.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Themes |