Posts Tagged by heather bruegl

“A lot of my work is based on identity and how I relate to my culture, my experiences of being Native, and growing up inside and outside and bouncing back and forth in the community. I explore beadwork in my pieces; I explore florals and storytelling.” —Maggie Thompson (Fond du Lac Ojibwe).

This year, The Henry Ford took steps toward building community with Indigenous nations by expanding the institution’s Artists in Residence program, offered annually in Greenfield Village. To kick off Celebrate Indigenous History programming, we welcomed Maggie Thompson (Fond du Lac Ojibwe) as the inaugural Indigenous Artist in Residence.

Maggie Thompson begins to weave in Greenfield Village Weaving Shop, October 2025. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Thompson was born and raised in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and her Ojibwe heritage comes from her father's side. Inspired from a young age, Maggie was creating art by the time she was in the fourth grade. Her mother is a painter, and she has been inspired by other Indigenous artists, including Jim Denomie (Ojibwe) and Dyani White Hawk (Lakota).

She received her bachelor of fine arts in textiles at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 2013. The following year, she mounted her first solo exhibition, Where I Fit at All My Relations Arts in Minneapolis. In 2024, her work was included in the exhibition The Shape of Power: Stories of Race and American Sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. And most recently, she was featured at the Detroit Institute of Arts’ celebrated 2025 exhibition, Contemporary Anishinaabe Art: A Continuation.

Detail of weaving by Maggie Thompson during the inaugural Indigenous Artist in Residence, October 2025. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Thompson has been awarded several grants and awards, including the All My Relations and Bockley Gallery Jim Denomie Memorial Scholarship and the Jerome Foundation Jerome Hill Artist Fellowship. Her work is represented in the collections of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Minnesota Museum of American Art, and the Field Museum, among others. In addition to her arts practice, Maggie runs a knitwear business called Makwa Studio—an Indigenous-run space that promotes Indigenous creativity, education, and collaboration.

During her residency in Greenfield Village, Thompson activated the Weaving Shop located in Liberty Craftworks. This building—a converted 1840s cotton mill from Bryan County, Georgia—is a popular experience for guests to see daily demonstrations of historic textile production on our many working looms. While Thompson does use traditional weaving materials such as natural fibers in her work, during her residency she relied on nontraditional materials such as nylon monofilament (better known as fishing line) and hollow, plastic, oxygen tubes that she filled with red seed beads.

Maggie Thompson’s weaving in progress, Greenfield Village Weaving Shop, October 2025. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Thompson’s recent weaving projects use nontraditional materials to talk about complex topics that affect many families across the country and within Indian Country: substance use, addiction, and recovery. Many issues contribute to the high rates of substance use among Indigenous populations especially. Poverty, historical trauma, discrimination, and racism—and lack of health insurance—all play a role. A 2018 survey by the American Addiction Centers reports that 10% of Indigenous Americans have a substance use disorder and 7.1% have an alcohol use disorder. These numbers make it so that Indigenous people living in the United States have rates of addiction higher than any other group. With the work that she created at the Weaving Shop, Maggie hopes to raise awareness of these issues.

Maggie Thompson holds up the work created during her residency at The Henry Ford. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation that forever changed the lives of many people of color in the United States and set the course for other groups to pursue their full rights as citizens. Yet, despite the successful legislation, many Black people and other people of color across the United States, particularly in the South, continued to be denied the right to vote.

“Do All Americans Have the Right to Vote?” An address by Barry Bingham, April 9, 1939. / THF289023

Do all Americans have the right to vote?

This question has been a concern for decades, particularly before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 15th Amendment prohibits voting discrimination based on race, yet barriers still existed at that time that limit access to voting. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses made it all but impossible for many groups of people to exercise the rights granted to them in the 15th Amendment — rights that were repeatedly violated.

Grassroots organizing had begun in many areas in the South, and Selma, Alabama, became the center of the movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) worked to register people to vote there for months in 1965. Their work did not go unnoticed. Soon, major players in the movement, such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, were making their way to Selma. The fight for voting rights eventually led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Local groups in the Selma area were also doing the hard work. Members of the Dallas County Voters League, known as the Courageous Eight, worked to register people to vote in Dallas County, Alabama. Though they were told multiple times to cease their activities, they did not. These community leaders were committed to securing the vote for themselves and their community.

The figures of the voting rights movement go beyond the names you may already know. Nationally recognizable figures depended on local activists—everyday people who put their lives and livelihoods on the line. One such family, the Jacksons of Selma, rose to the occasion by opening their home to provide shelter, nourishment, and peace, all while putting their personal safety at risk. Their sacrifice helped to create a safe space for the movement’s leaders to strategize and rest.

Pajamas worn by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while at the Jackson’s Home. / THF802666

Mrs. Richie Sherrod Jean Jackson took pride in ensuring that her guests felt comfortable and welcomed. Dr. Jackson provided Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with pajamas, and Mrs. Jackson fueled the movement with nourishment. The Jackson’s young daughter, Jawana, would listen to the stories her Uncle Martin would tell. But the family did more than provide a haven. They became involved civically as well.

In November 1958, Dr. Sullivan Jackson testified before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Established as part of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the commission investigated voter discrimination. The hearings were held over a period of two months, between 1958 and 1959. The Commission had several people testify, including Dr. Jackson, who spent hours preparing for his testimony. The Commission assumed the responsibility of voter registration, with a focus on Alabama. Speaking out had its own set of hardships. The Jacksons and others who testified often faced economic repercussions.

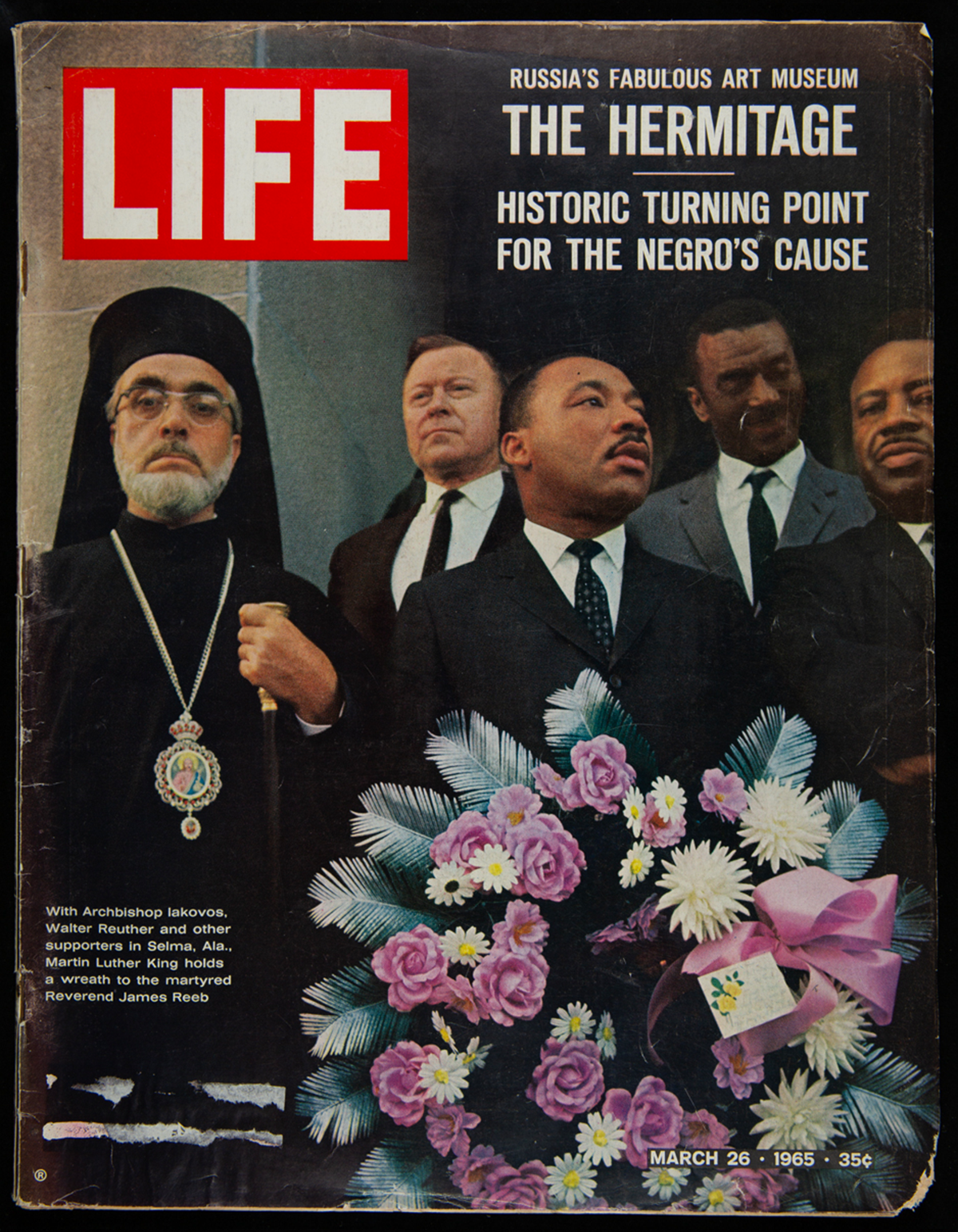

“Life” Magazine, March 19, 1965. / THF715919

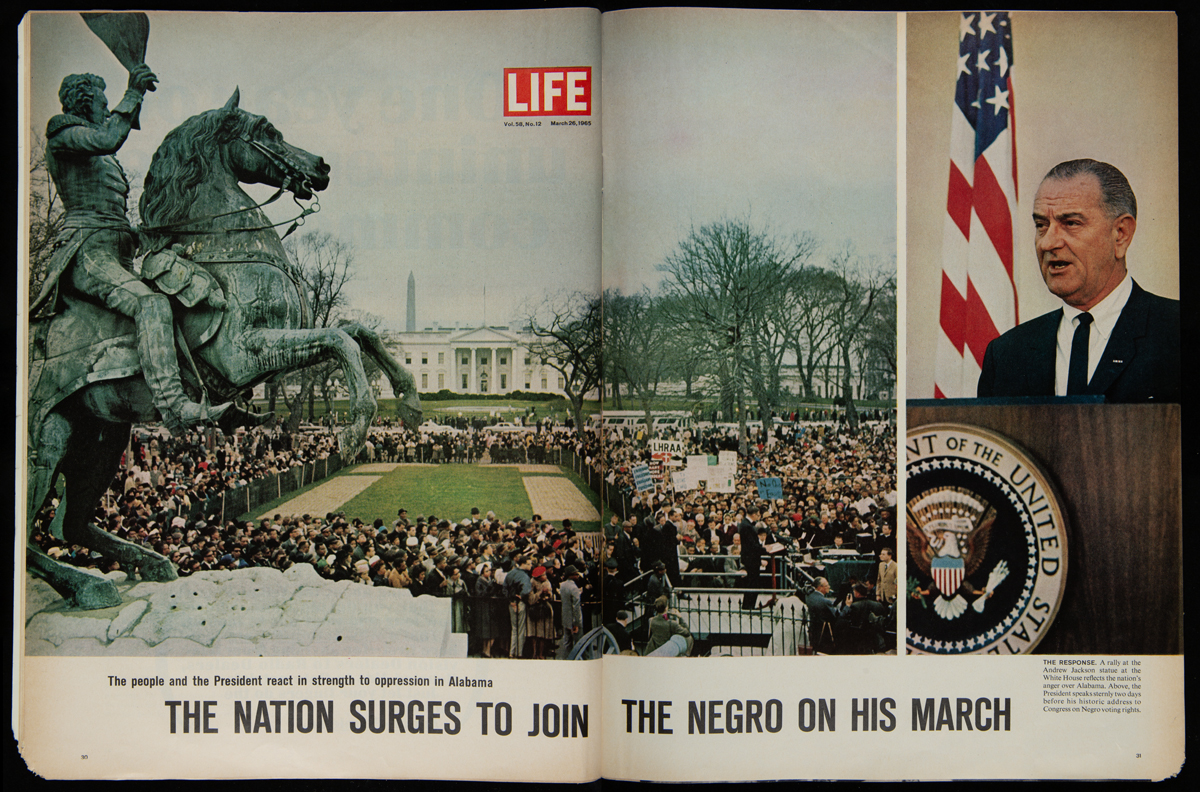

Voting is a fundamental right. In the United States, this concept has been ignored more than once. The denial of voting rights to people of color across the country came into sharp focus in March of 1965 in Selma, Alabama. After March 7, 1965—known as Bloody Sunday—Dr. King called for clergy members to go to Selma. Clergy, including Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Rev. James Reeb, among many others, answered the call. On March 15, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed the nation and instructed Congress to introduce and pass a Voting Rights Act.

Two days after President Johnson gave his “American Promise” speech, on March 17, 1965, the Voting Rights Act was introduced into Congress. The Senate began its debate on the bill on April 22. Eventually, the Voting Rights Act was passed after much debate, and President Johnson signed it on August 6, 1965. Thus, it enshrined the enforcement of the 15th Amendment and ensured that no one was denied the right to vote.

Letter from Rev. Ralph Abernathy thanking her for opening her home to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. / THF721760

While the Jackson House remained a family home at its core, it also offered refuge and peace during a time of great turmoil. While in Selma, Dr. King stayed with the Jacksons. Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a member of the leadership team for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, sent Mrs. Jackson reimbursement and letters of gratitude. The Jacksons provided crucial hospitality and support, even if it meant putting their own lives at risk.

As we celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, it is essential to remember all those who were involved in the process.

Are you registered to vote? To find out if you are registered or to register, please visit the following websites:

Michigan Residents

To Check Your State

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford.

“Indian Country”: The Work of Bobby “Dues” Wilson

Representation matters. And for communities that are marginalized, representation in mainstream media can feel like a long overdue recognition that can change everything.

For the Indigenous community, mainstream recognition came with the introduction of the Hulu FX original series Reservation Dogs. Created by 2024 MacArthur Fellow Sterlin Harjo (Seminole/Muscogee Creek) and Taika Waititi (Māori/Ashkenazi Jewish/Irish/Scottish/English), the series explored the adventures and growing pains of four Indigenous teenagers growing up on the Muscogee Reservation in rural Oklahoma. They deal with teenage shenanigans, growing up, and coping with the death of their friend Daniel, who dies before the events of season one take place.

The show featured a primarily Indigenous cast. The actors who played main characters included Devery Jacobs (Mohawk) as Elora, D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai (Oji-Cree) as Bear, Lane Factor (Caddo/Seminole/Muscogee Creek) as Cheese, and Paulina Alexis (Alexis Nakota) as Willie Jack. There were also appearances from recurring Indigenous actors such as Zahn McClarnon (Standing Rock Lakota), Dallas Goldtooth (Mdewakanton Dakota/Diné), Gary Farmer (Grand River Cayuga) and Jana Schmieding (Cheyenne River Lakota).

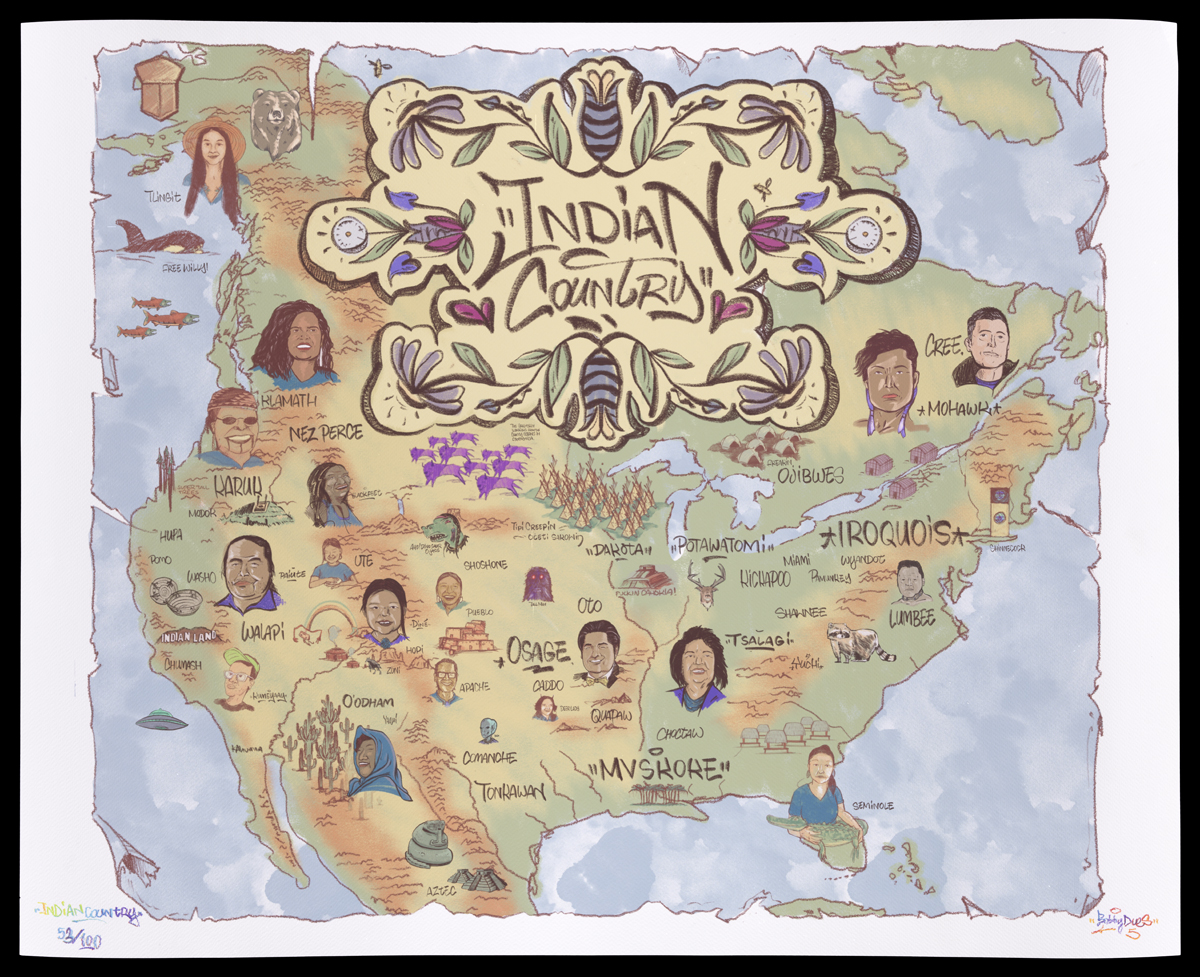

"Indian Country" map created by Bobby “Dues” Wilson (Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota). From the Collections of The Henry Ford. / THF725033

The show focused on a number of topics within Indigenous communities, such as loss and suicide, poverty, boarding schools, storytelling, ceremonies, traditions, friendship, and adventures. It brought issues in Indian Country to the mainstream and an international audience. The show also featured works by Indigenous fashion designers, artists, musicians, and writers. One such artist is Bobby “Dues” Wilson (Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota).

Known primarily as Bobby Dues, he works as a multimedia artist in the mediums of poetry, acting, comedy, and visual arts. A version of the print above appeared in Season 2, episode 10 of Reservation Dogs.Titled “Indian Country Map,” it depicts the United States, Canada, and parts of Mexico and shows the land as Indigenous land. It plays on the term Indian Country, which is defined as lands the federal government holds in trust for tribal nations. This includes reservations and allotments where title to the land has not been severed. It also refers to the Oklahoma territory, which was deemed Indian Country during the Indian Removal period.

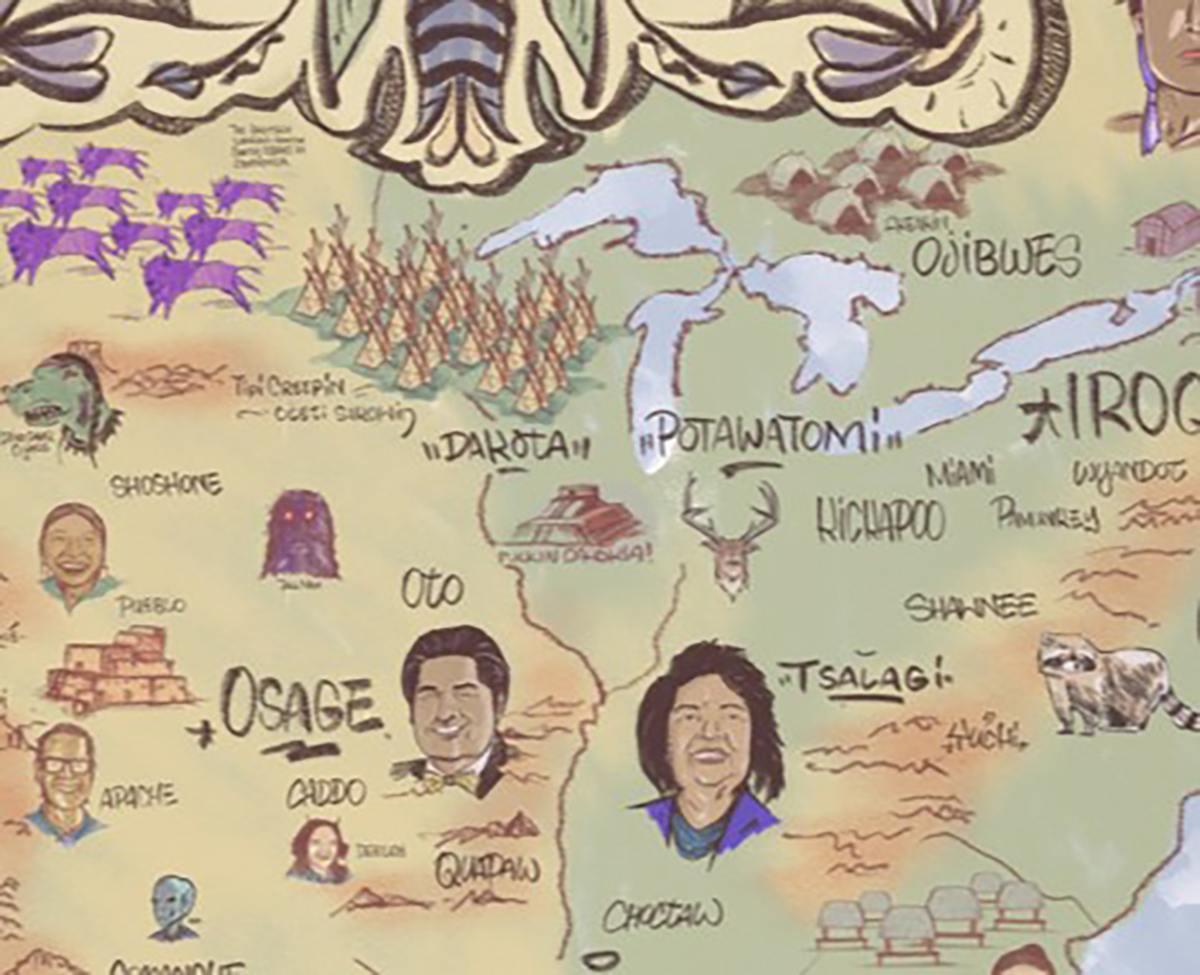

A close-up of “Indian Country” shows Wilma Mankiller, the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. From the collections of The Henry Ford. / THF725033

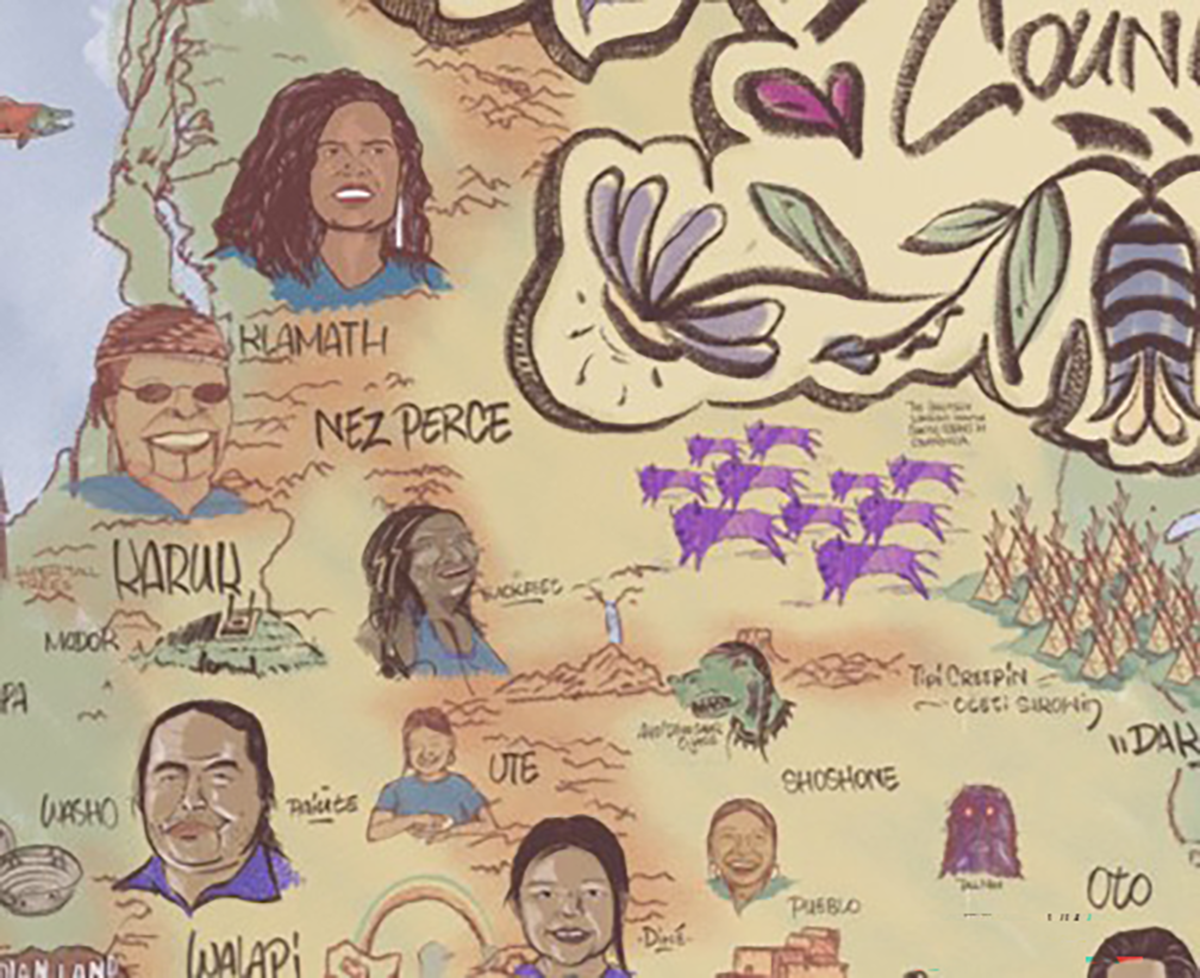

The artist, who was asked to create this map for who was asked to create this map for Reservation Dogs, depicts the culture, beauty, and uniqueness of the land and those who call it home. On the map, the artist calls out the many different tribal nations that called the land home and even features some notable people. In the area between Oklahoma and the southeastern part of the United States, we can see Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee), the first female principal chief of the Cherokee nation. The nation was removed to Oklahoma during Indian removal in a route that was called the Trail of Tears. Contemporary Indigenous artist Natalie Ball (Black, Modoc, and Klamath) is featured in her homelands in the Pacific Northwest. Ball also serves as a tribal council member for the Klamath Tribes Tribal Council.

A close-up of “Indian Country” shows Natalie Ball, artist and Tribal Council Member (Black, Modoc, and Klamath). From the collections of The Henry Ford. / THF725033

Wilson's “Indian Country” map shows the breadth of Indigenous history and knowledge still carried today. On Reservation Dogs, it played a role on a television show that included a primarily Indigenous cast and writers — that was watched by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. The show — and this map — are powerful portrayals of Indian Country that show Indigenous people as contemporary nations and not something of the past.

Are you curious about the land that you live on? You can learn more with these resources:

The Henry Ford's Land Acknowledgement

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford.

The American Promise: The Speech that Changed a Movement

Selma is a sleepy little town in Alabama that has an extraordinary history. Located on the shores of the Alabama River in the heart of Dallas County, Selma is also home to the Jackson family.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson met Miss Richie Jean Sherrod at a family picnic the summer of her junior year in 1953. The meeting was brief, but Dr. Jackson was smitten, and he called Miss Sherrod the next day and asked her for a date. The two started dating steadily after that.

Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson on their wedding day, March 15, 1958. / THF708474

While Richie Jean attended college in Montgomery, Sullivan would often drive over to see her, and they would go out to eat and spend time together. After Richie Jean graduated from college in 1954, the situation changed as both tried to navigate their worlds and have successful careers, and the two decided to end their relationship. But the universe had different plans. After a time, they were soon back together, and on March 15, 1958, they were married and began to create a life together that would shape their roles in civil rights and voting rights activism in ways they never imagined.

Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson on their wedding day with family. / THF708475

It was March 1965, and many thought the fight for civil rights was over. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been signed the year before, and many wrongs had been righted. However, the fight for equality and the right to vote was far from over. Things would reach a point where the president at the time, Lyndon Baines Johnson, would address Congress and demand something be done.

The movement for voting rights spread throughout the South in the United States, but its center was Selma, Alabama. In February 1965, a group of activists and protestors gathered outside Zion United Methodist Church in Marion, Alabama, about 26 miles northwest of Selma. One such protester was Jimmie Lee Jackson. Though they share a last name, he is not related to that Jackson family of Selma. He was at the protest with his mother, Viola Jackson, and his grandfather, Cager Lee. While trying to protect his mother from the escalation in violence, Jimmie Lee was shot twice in the stomach by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler. Eight days later, he died from his wounds.

The death of Jimmie Lee Jackson became one of the factors in the march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights. The first attempt at this march resulted in Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965. That event and the subsequent Turnaround Tuesday March on March 9, 1965, led to President Johnson giving one of the most powerful speeches in support of his presidency.

Life Magazine, dated March 26, 1965, discusses the Voting Rights Movement and President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s March 15, 1965, speech throwing his support behind the Voting Rights Act. / THF715927

It was March 15, 1965, when members of the Jackson family and guests gathered in their homes to listen to President Johnson give this speech. This was also the seventh wedding anniversary for “Sully” and Richie Jean. The President began:

“At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.”

His words bring back memories of the American Revolution and the Civil War, two events in which the country fought for freedom. As the president continues with The American Promise speech, he brings up the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson while discussing the violence inflicted upon those who merely wish to register to vote.

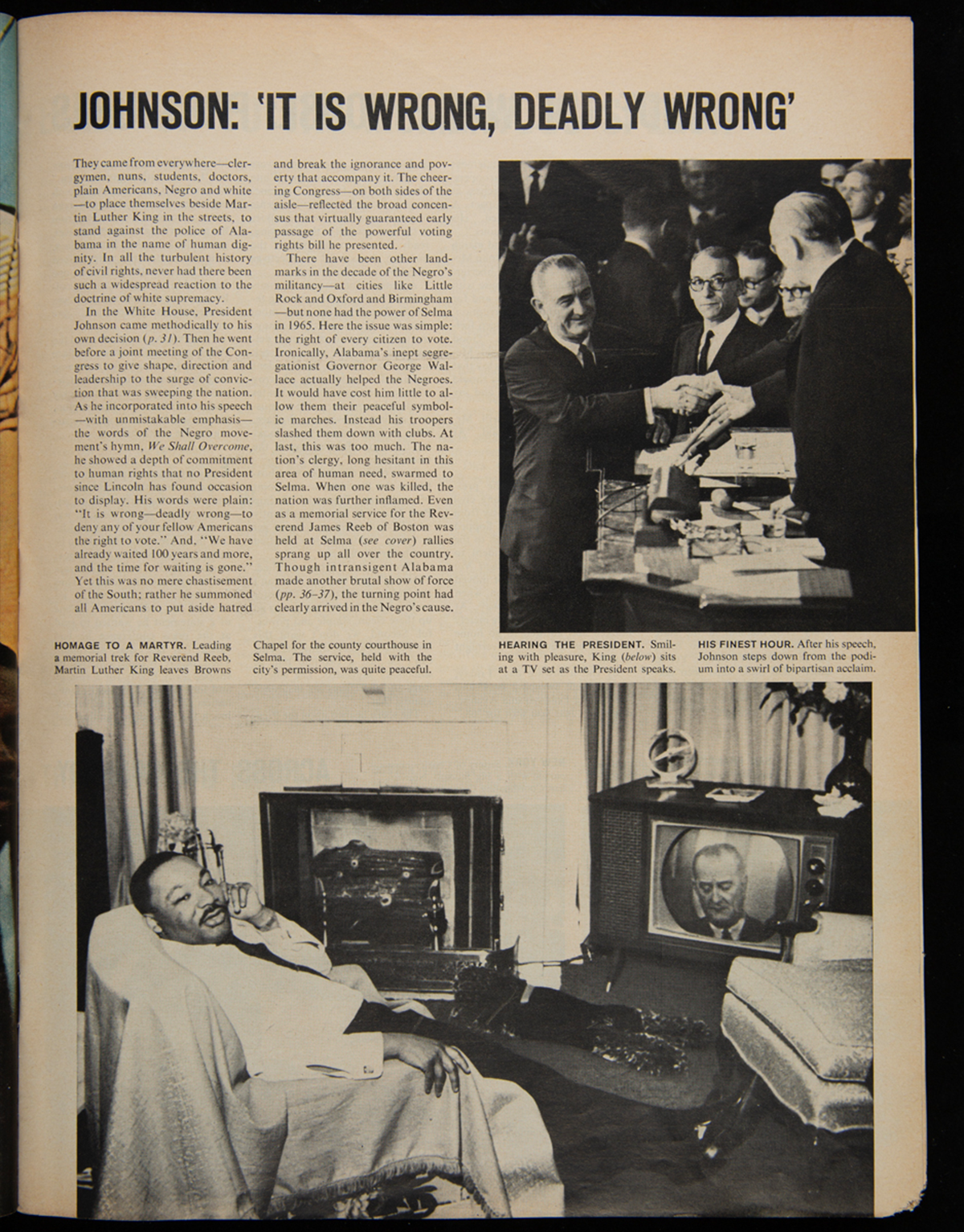

Life Magazine, dated March 26, 1965. / THF715929

The speech was written by writer and presidential advisor Richard Goodwin, who also worked for President John F. Kennedy. The President had decided on Sunday, March 14, that he would address the country the next night, March 15. Goodwin was assigned to write the speech at the last moment and had only eight hours to write. As a Jewish American, Goodwin pulled from his own experiences with anti-Semitic prejudice and discrimination.

The American Promise, more commonly known as the “We Shall Overcome” speech, hits on historic and contemporary moments leading to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Invoking Patrick Henry’s famous “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” to the Declaration of Independence's statement that “All men are created equal,” the speech is the argument. It makes the case for a Voting Rights Act.

The President spoke about the barriers that had been put in place on Black Americans, from poll taxes to literacy tests, while also invoking the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, which guaranteed Black men the right to vote. This right was not always upheld.

The speech was 48 minutes and 53 seconds long. Seventy million Americans watched it, including the Jackson family and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The White House received 1,436 telegrams of support and 82 telegrams against the idea of a Voting Rights Act, and LBJ was interrupted over 40 times for applause.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr watched President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s speech from the living room of the Jackson Home on March 15, 1965. Photo feature in Life Magazine, March 26, 1965. / THF715931

In his speech, the President discussed the need for the Voting Rights Act, his intention to push Congress to pass it, and how passing that act fulfills an American promise to all citizens to be able to vote for their leaders.

Pulling from a song that had become the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, President Johnson signaled that he heard the activists working on the ground in Selma and would answer the call. And the speech that reiterated the American promise forever would be known by a different name: We Shall Overcome.

“Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

The full text of the speech can be found courtesy of The American Presidency Project.

A video excerpt of the speech can be found at the LBJ Presidential Library.

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford. This blog is part of a series exploring the history of the Jackson Home, opening in Greenfield Village, 2026.

On April 30, 1789, 235 years ago, in the nation’s first capital of New York, George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the newly formed United States of America. From that moment on, many aspects of Washington’s legacy would be built on myth, leaving out important parts of history that would help us understand the man and tell a fuller story. This isn’t to say that Washington didn’t do extraordinary things in his lifetime. Still, when we peel away the layers, we find that he was an ordinary man who lived in exceptional times and wasn’t as perfect as he is often portrayed.

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, on Popes Creek Plantation, (also known as Wakefield) in Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1734, the Washington family moved to another property they owned, Little Hunting Creek Plantation, which was later renamed Mount Vernon. While Washington never received a formal education, he did have access to books and a private tutor. At the same time, he studied geometry and trigonometry on his own, for his first job as a surveyor.

Continue Reading