African American Workers at Ford Motor Company

| Written by | Peter Kalinski |

|---|---|

| Published | 2/26/2013 |

African American Workers at Ford Motor Company

| Written by | Peter Kalinski |

|---|---|

| Published | 2/26/2013 |

No single reason can sufficiently explain why in a brief period between 1910 and 1920, nearly half a million Southern Blacks moved from farms, villages, towns and cities to the North, starting what would ultimately be a 50-year migration of millions. What would be known as the Great Migration was the result of a combination of fundamental social, political and economic structural problems in the South and an exploding Northern economy. Southern Blacks streamed in the thousands and hundreds of thousands throughout the industrial cities of the North to fill the work rolls of factories desperate for cheap labor. Better wages, however, were not the only pull that lured migrants north. Crushing social and political oppression and economic peonage in the South provided major impetus to Blacks throughout the South seeking a better life. Detroit, with its automotive and war industries, was one of the main destinations for thousands of Southern Black migrants.

In 1910 Detroit’s population was 465,766, with a small but steadily growing Black population of 5,741. By 1920 post-war economic growth and a large migration of Southerners to the industrialized North more than doubled the city’s population to 993,678, an overall increase of 113 percent from 1910. Most startling, at least for white Detroiters, was the growth of the city’s Black population to 40,838, with most of that growth occurring between 1915 and 1920.

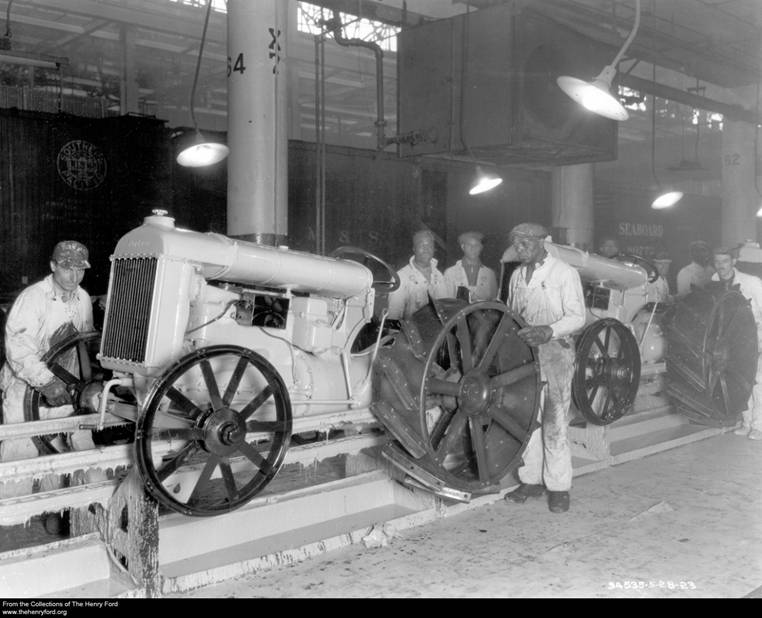

Photo: P.833.34535 Fordson Tractor Assembly Line at the Ford Rouge Plant, 1923

Before the war, Detroit’s small Black community was barely represented in the city’s industrial workforce. World War I production created the demand for larger numbers of workers and served as an entry point for Black workers into the industrial economy. Growing numbers of Southern migrants made their way to Detroit and specifically to Ford Motor Company to meet increased production for military and consumer demands.

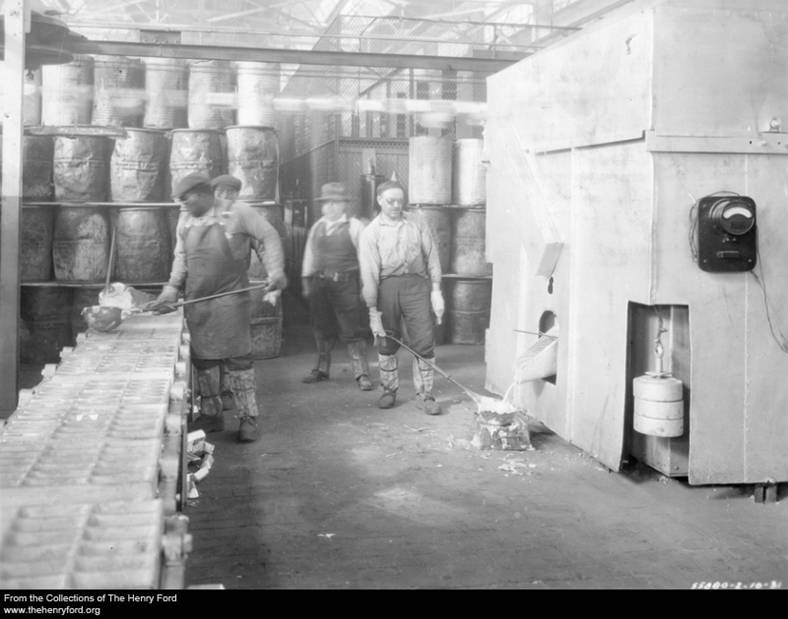

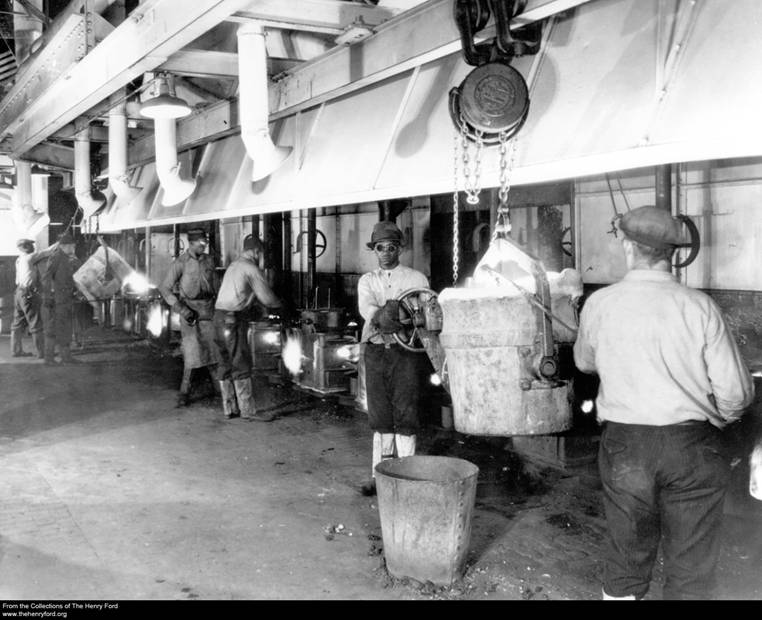

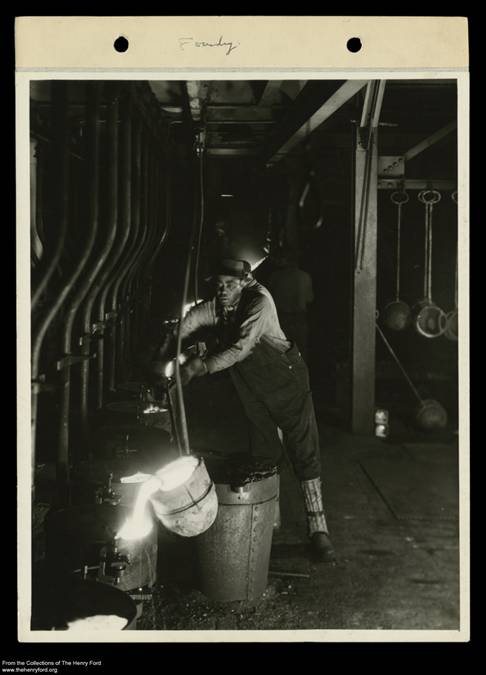

By the end of World War I over 8,000 black workers were employed in the city’s auto industry, with 1,675 working at Ford. Many of Ford’s Black employees worked as janitors and cleaners or in the dirty and dangerous blast furnaces and foundries at the growing River Rouge Plant’s massive blast furnaces and foundries. But some were employed as skilled machinists or factory foremen, or in white-collar positions. Ford paid equal wages for equal work, with Blacks and whites earning the same pay in the same posts. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Ford Motor Company was the largest employer of Black workers in the city, due in part to Henry Ford’s personal relationships with leading Black ministers. Church leaders in the Black community helped secure employment for hundreds and possibly thousands, but more importantly, they also helped to mediate conflicts between white and Black workers.

Photo: P.833.55880 African American workers at Ford Motor Company’s Rouge River Plant Cyanide Foundry, 1931

Photo: P.833.57788 Foundry Workers at Ford Rouge Plant, 1933

Photo: P.833.59567 Pouring Hot Metal into Molds at Ford Rouge Plant Foundry, Dearborn, Michigan, 1934

In addition to jobs, Ford Motor Company provided social welfare services to predominantly Black suburban communities in Inkster and Garden City during the depths of the Great Depression. Ford provided housing and fuel allowances as well as low-interest, short-term loans to its employees living in those communities. Additionally, Ford built community centers, refurbished several schools and ran company commissaries that provided inexpensive retail goods and groceries. (You can learn more about the complicated history of Ford and Inkster in The Search for Home.)

You can learn more by visiting the Benson Ford Research Center and our online catalog.

Peter Kalinski is Racing Collections Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post was last updated in 2020 with additional text by Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Series | |

Themes |