Information at Your Fingertips: Encyclopedias through History

| Written by | Sarah Andrus |

|---|---|

| Published | 3/30/2021 |

Information at Your Fingertips: Encyclopedias through History

| Written by | Sarah Andrus |

|---|---|

| Published | 3/30/2021 |

What is the first thing you do when you have a question? Is your answer to type it into a conveniently located search bar? What would you do if that were not an option? How would you find reliable answers? Who would you ask? What sources would you trust?

The answer for most previous generations would be: Encyclopedias.

Encyclopedias are collections of large scopes of knowledge that are written by subject experts, vetted by editors, and published for the masses. They have been helping students, parents, and armchair experts for centuries—well before the dawn of the Internet. They also have a unique history all their own.

For the full story on encyclopedias, you have to travel back almost 2,000 years. In the Western world, the trend to document and disseminate knowledge starts with people like Pliny the Elder. Pliny’s Naturalis Historia is the Western world’s first encyclopedia to have survived the ages. Published around 77 CE, the 37 chapters in Naturalis Historia do not resemble a modern-day encyclopedia, but do include a multitude of facts from astrology to zoology.

The Naturalis Historia is only the start of what became a trend to document knowledge. The Middle Ages brought more encyclopedists like Pliny the Elder. These men—and yes, they were always men—were often associated with the church. Their encyclopedias were full of both knowledge and morality. These works, which were handwritten, could only be produced by monks with the time and dedication for such pursuits, and were often flawed. By having a single person attempt to compile the sum of all human knowledge, there were obvious gaps and biases. This, paired with the involvement of the church, meant that information was morally coded and gate-kept, as these early encyclopedias were far too valuable to leave monasteries.

It wasn’t until the 1750s that there was a popular encyclopedia that was widely available.![Encyclopedia: Or Dictionary of Sciences, Arts, and Trades, Volume 1 [Text], 1751 / title page Page with text in French and decorative image of figure with wings and flowing loincloth](https://www.thehenryford.org/images/thehenryfordlibraries/blog-images/thf620980.jpg?sfvrsn=34da3e80_0)

The Encyclopédie aimed to be a one-stop shop for all knowledge for the every-person. / THF620980

To solve the issue of a single contributor, and to make information available for a wide swath of the population, Denis Diderot published a total of 28 volumes of the now-infamous Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (translated to Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Discovery of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts). The Encyclopédie embodies the thoughts of the Enlightenment and was aimed at providing average citizens with knowledge that would not have been available to their ancestors. This was controversial at the time, as it moved access to knowledge away from religious authorities and presented it in a more democratic manner.![Encyclopedia: Or Dictionary of Sciences, Arts, and Trades, Volume 1 [Text], 1751 / fold out chart Page with chart containing text in French](https://www.thehenryford.org/images/thehenryfordlibraries/blog-images/thf620982.jpg?sfvrsn=5fb9579b_0)

The Encyclopédie used this knowledge tree for structure. The main branches are History, Reason, and Imagination. / THF620982

Here, Diderot recruited experts in specific fields to write on topics they were familiar. This allowed a wider scope of information and helped to guarantee the validity of each entry. Diderot was able to recruit well-known thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu to write entries for the encyclopedia, and even took on sections related to mechanical arts, economics, and a smattering of other topics himself.

Diderot’s Encyclopédie laid the groundwork for the next in the line of popular encyclopedias, an encyclopedia that would change the way entire populations accessed information—Britannica.

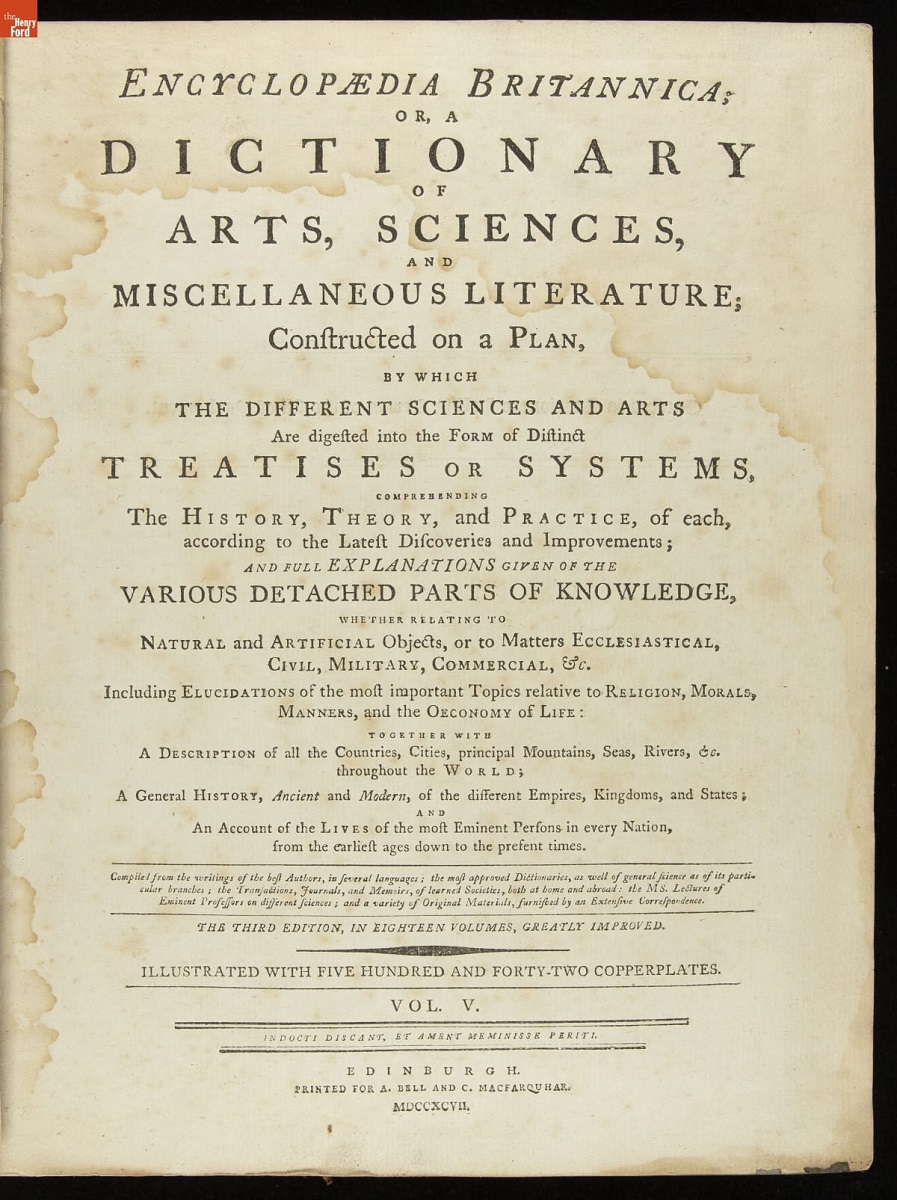

The Encyclopedia Britannica was devised by Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell, who conceived of, printed, and designed all copper plates for the first edition. Another Enlightenment-inspired project, Britannica was first published serially in pamphlet form. Each edition of Britannica grew in length and scope, and with these changes, it grew in popularity.

The 1797 third edition of Encyclopedia Britannica more than doubled the scope of the previous two editions and started Britannica on the path to becoming a household name across the globe. / THF620752

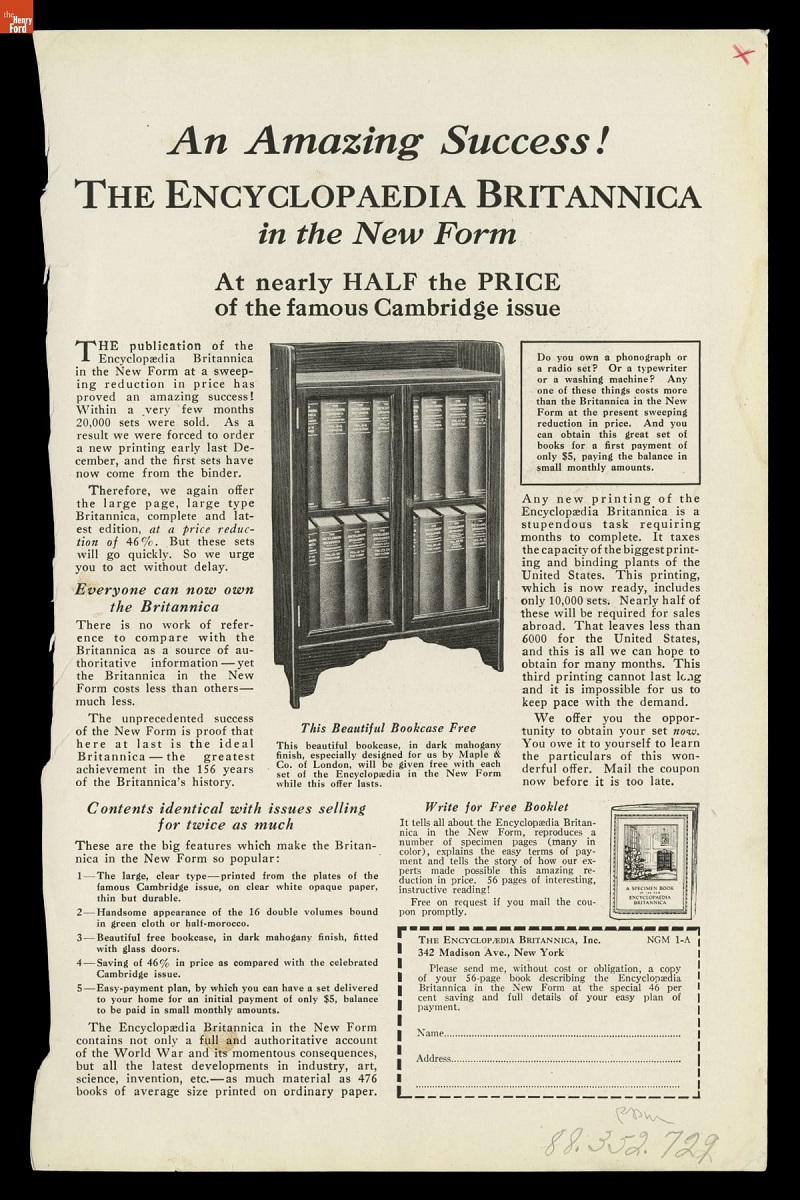

Britannica is notable for a variety of reasons. It is the first encyclopedia to implement constant revisions to ensure the relevance and accuracy of information. By the 11th edition, it was published in complete sets, instead of serialized as it was written, and an additional index was developed to assist with organization of information. All these changes, plus a shift to American ownership, helped Britannica to skyrocket in popularity. By the 1920s, Sears Roebuck took ownership of Britannica and was able to sell complete sets through their mail-order catalogs.

This ad for a set of Encyclopedia Britannica grabs readers by informing them they will cost less than a typewriter or washing machine. / THF135870

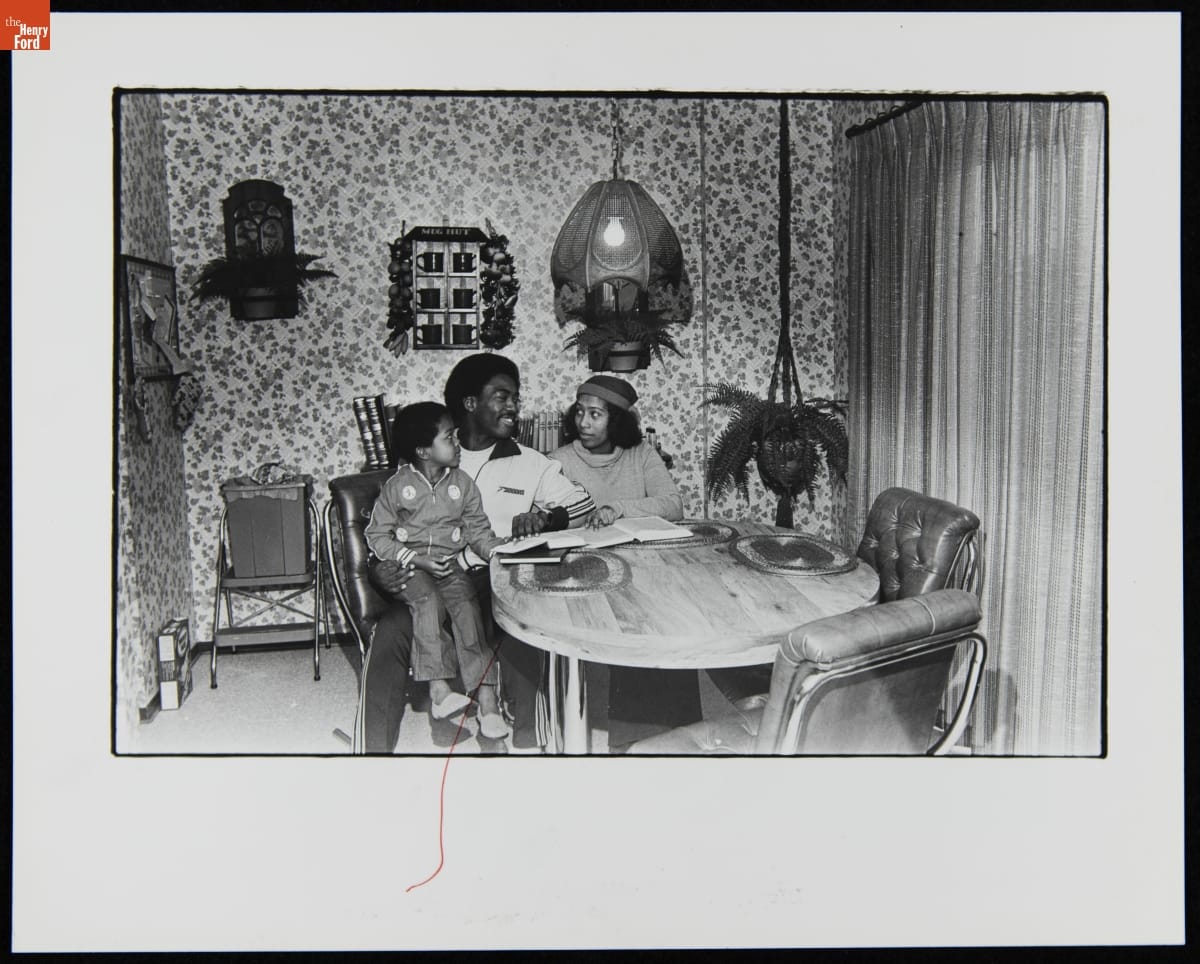

The mass publishing of encyclopedias opened a whole world of information to the middle class. People no longer needed to camp out at libraries to finish papers or conduct basic research. Encyclopedias could be bought on installment plans for household and personal use. Other popular encyclopedias, like Americana and World Book, also flourished during this time.

Families would store encyclopedia collections on their bookshelves, often in public areas of their homes. This made them a small status symbol to show off for guests. / THF620097

Encyclopedias remained relevant through the advent of the Internet age, but encyclopedias do have one major flaw—they are out of date the moment they are printed. This, coupled with the cost of owning a full set of encyclopedias plus any additional supplements, led companies like Britannica to cease print publication in 2010.

That isn’t to say the idea behind encyclopedias has gone the way of the print publications. Sites like Wikipedia crowdsource information to create a massive Internet encyclopedia. Britannica, World Book, and others have adopted to online models. This method allows for more entries, up-to-date information, and easier access.

Sarah Andrus is Librarian at The Henry Ford.

Keywords |

|---|