Día de Muertos: The Living and the Dead, Together Again

Mourning takes many forms. But can it ever be joyful? For celebrants of the holiday Día de Muertos, the answer is yes.

Día de Muertos, also known as Día de los Muertos or Day of the Dead, traces its roots back to the celebrations of pre-Hispanic Indigenous Mexicans, in particular the Mexica/Mexihcah (Aztecs). For them, death was considered an important part of the cycle of balance, and they practiced rituals to both prepare the recently deceased for the afterlife, and to honor those already departed. One such ritual was a two-month-long feast in late summer celebrating the dead; the first month was dedicated to honoring children, and the second to adults.

When the Spanish arrived in Mexico, they sought to drive out the old traditions, establishing mandatory church burials, abolishing certain mourning and funerary rites, enacting a grave tax, and banning feasting during burials, funerals, or on “Days of the Dead.” These traditions persisted, however, and eventually melded with the Catholic influence of the Spanish, who celebrated All Saints Day and All Souls Day, to create Día de Muertos.

Continue ReadingMary Judge: Fixture of Detroit’s Central Market

Through determination and resourcefulness, Mary Judge stood out from the other hucksters at Detroit’s Central Market in the latter half of the 19th century. Poor, single and an immigrant, Judge managed to make a living — and a name for herself — at a time when such women seldom gained financial independence.

Born in Sligo County, Ireland, around 1825, Judge emigrated with her parents as a baby, settled in Quebec, received her education at a convent and became a nun. Judge left her order but remained a devout Catholic. When and how she came to the Midwest remains unclear, but a Detroit-based relative of her legal guardian helped set her up as a huckster at the vegetable building at Central Market, the city’s bustling agricultural marketplace, by 1863.

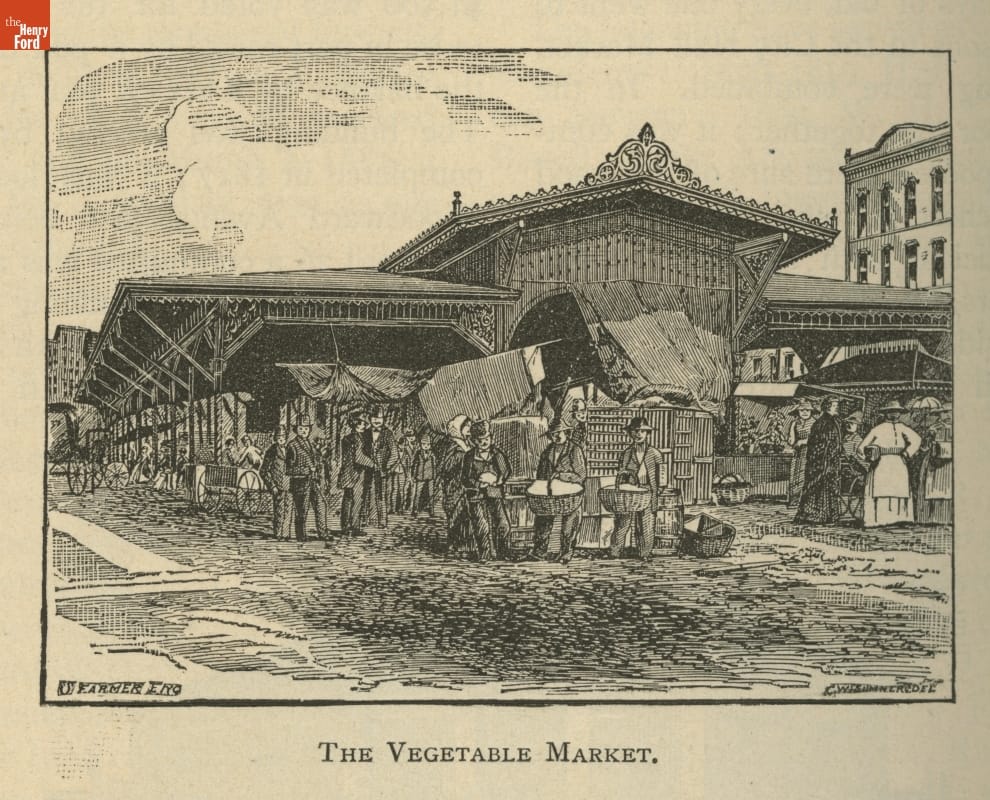

The vegetable building at Detroit Central Market, 1884. / THF139107

Continue Reading

Unions and Mandela: A Fight for Equality

Detroit. What comes to mind when you think about Detroit? Cars. Motown, of course! Labor unions. All these make sense, but do you also think of Nelson Mandela? Probably not. And United Auto Workers (UAW) support of Mandela? It probably never even crosses your mind. For most people, the first and frequently only thought that comes to mind is apartheid and Mandela's fight to stop the practice in South Africa.

Mandela was a union man. When he was president of South Africa (1994-1999), he declared, "The kind of democracy that we all seek to build demands that we deepen and broaden the rights of all citizens. This includes a culture of workers’ rights." He understood the importance of unions and the rights of workers. He knew that the organization of workers was vital to having a free and just society.

Button welcoming Nelson Mandela to Detroit on his 1990 Freedom Tour. / THF196997

Continue Reading

Honoring Indiana Autos at Old Car Festival 2023

Ford Model A cars were easy to find at Old Car Festival, but our spotlight this year fell on Indiana-based automakers. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Auto enthusiasts, bicyclists and folks just looking for a little fun descended on Greenfield Village over the September 9-10 weekend as we celebrated our 2023 Old Car Festival. More than 600 vintage automobiles and some 250 bicycles — none dating more recently than 1932 — participated in this beloved late-summer tradition.

Each year at the show, we spotlight a special theme. Generally, it’s a particular make or model or a specific style of automobile. (Last year, for example, we featured early American luxury cars.) For 2023, we went in a different direction, instead focusing our spotlight on a state. Our “Indiana Autos” theme allowed us to honor the many marques of the Hoosier State. More than 400 distinct automobile brands called Indiana home at one time or another, and the state’s automotive industry was second only to Michigan’s in its size and significance. From premium luxury vehicles to the greatest spectacle in racing, our Indiana neighbors had it all.

Continue ReadingBuilt to Serve: Detroit Central Market

Detroit Central Market vegetable shed in Greenfield Village, 2022. / THF190482

Cities like Detroit built public markets where growers, fish mongers, vendors and peddlers sold directly to customers. People of all ages, many nationalities and various occupations crossed paths in these spaces. Vendors paid rent and tried to outdo each other with their vegetables, fruits, flowers and other wares. Some hawked their services as chimney sweeps or day laborers. Customers, attracted by the variety, stayed for entertainment.

Detroit's original city hall building with market sheds behind, 1861-1871. / Detail, THF623873

Continue Reading

Moving Milk on the Railroad

Milk cans are visible on the carts at center in this view of the Leslie, Michigan, railroad depot in 1910. / THF204974

Many Americans consider milk an essential part of daily life. For more than a century, milk’s production has followed the same basic pattern. Raw milk is gathered at dairy farms, it’s taken to processors for pasteurization and bottling, and then it’s distributed to consumers. But milk is a perishable product that spoils quickly. In the 19th century, transporting raw milk from countryside farms to urban processors was a task beyond the limited range and speed of horse-drawn vehicles. Railroads rose to the challenge and developed a steady business moving milk.

Continue ReadingElsie the Borden Cow: Milk’s Marketing Miracle

Elsie the Borden Cow, depicted in a circa 1961 recipe booklet. Note her maternal apron and ever-present necklace of flowers. / Detail, THF296067

Mascots appear on so many of the products we see in advertisements or while shopping, it can be easy to look right past them. Or we might seek out our favorites — characters we love so much, they’ve secured our allegiance to particular brands. With names and backstories, these mascots can seem at once familiar and absurd. Why do companies invest so much in developing them? Because, under the right circumstances — as with Elsie the Borden Cow — mascots can resonate deeply with consumers, boosting sales and generating brand loyalty.

Continue ReadingRuPaul, Drag Race, and the “Werk” that Came Before

"We’re all born naked, and the rest is drag.” — RuPaul

RuPaul Charles was born on November 17, 1960 in San Diego, California. His parents, Ernestine “Toni” Fontenette and Irving Charles, divorced by the time he was 7; although Ru and his three sisters would continue to live with their mother, older twins Renetta and Renae played a major role in raising Ru. Toni was fiercely supportive of her son, though, despite struggling with her own depression, never doubting that he would be a star one day (a prediction that had been shared with her by a psychic). She would, of course, be correct.

As he grew up — eventually moving to Atlanta with Renetta, where he attended a performing arts school — RuPaul was inspired by divas like Diana Ross and Cher, the punk rock aesthetic and androgynous performers like David Bowie, the irreverence of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the drag queen and ballroom house founder Crystal LaBeija, and queer cult classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show; these icons would go on to shape his drag performance. In the 1980s, Ru began performing in bands, and producing and starring in underground films, including the Starbooty (also spelled as Starrbooty in some instances) trilogy, a send-up of Blaxploitation films.

Continue ReadingFarm-Made Cheese in a Big City Market

IMLS Agriculture & Environment Grant Work Continues

The Henry Ford received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to increase physical and digital access to agricultural and environmental artifacts. Staff from collections management, conservation, the photo studio, registrars and curatorial departments have worked with 1,200 items to date. Over the two-year grant period (September 2022 through August 2024), 1,750 objects will be conserved, cataloged, digitized and rehoused.

The IMLS grant has helped reunite several items donated by one farm family to The Henry Ford in 1973. These items were all used on a general farm owned and operated by William Saxony Rider (1857-1937) and his wife, Elizabeth Stephenson (1866-1948), in Almont, Michigan. Their daughter, Marion E. (1900-1974), remembered that her mother and father “made and marketed enough of this fine-tasting [cheddar] cheese to build a 300-acre farm.” That work likely occurred during the early 20th century, a time period described as the Golden Age of Agriculture, when market prices exceeded the cost of agricultural production and farm families prospered.

Continue ReadingFrom Work to Play: Industrial Locomotives and Park Trains

Opened in 1947, the Edaville Railroad quite literally transformed from an industrial railroad into an amusement attraction. / THF238726

Ellis D. Atwood only wanted to make his Massachusetts cranberry-farming operation more efficient. He’d purchased four steam locomotives and several railcars from narrow-gauge railroads in Maine, and he’d built 5.5 miles of track winding through his cranberry bogs. The trains hauled supplies into the bogs, and they carried harvested cranberries out of them. But then Atwood began offering rides at five cents a ticket.

Intentionally or not, Ellis Atwood discovered an entirely new business model for himself. Using his initials, EDA, for inspiration, Atwood named his operation the Edaville Railroad. Following his death in 1950, subsequent owners added rides and amusements and turned the operation into one of New England’s most popular destinations. The Edaville Railroad morphed from an industrial railroad into a “park train” – a railroad operated as part of a larger attraction.

Continue Reading