Monthly Archives: April 2025

Acquiring an Agras MG-1 Drone

"Agras MG-1" Drone, with remote control, battery, and battery charger, 2016. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF199347

Curators at The Henry Ford document milestones in their given areas of responsibility. For agriculture and environment collections, one significant recent development involves uses of uncrewed aerial technology — popularly known as drones — to apply growth enhancers (fertilizers) and plant protectors (herbicides and pesticides) to specific locations in fields, vineyards, and orchards. Curator Debra Reid began conversations with the Michigan Soybean Committee in 2023 to secure a drone for our collections to document this aspect of precision agriculture.

Drones flew on military missions, predominately, until the early 2000s. One example includes the 1918 Kettering Bug, described as the world's first "self-flying aerial torpedo.” As a Smithsonian Magazine article explained, “the simple, cheaply made 12-foot-long wooden biplane with a wingspan of nearly 15 feet” included “a 180-pound bomb. It was powered by a four-cylinder, 40-horsepower engine manufactured by Ford.” These precision-based technologies aimed to put fewer pilots at risk.

Employees of the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company Working on the Kettering Bug, 1918 / THF270430

Other drones in The Henry Ford’s collections address robotics in aerial photography and stunts.

3DRobotics Solo Drone, 2015-2016. Gift of Industrial Designers Society of America / THF193809

3D Robotics (3DR) released its Solo drone in 2015 to great fanfare. NBC News claimed the Solo, when paired with a GoPro HERO camera, could take Hollywood-quality shots. 3DR, the largest North American manufacturer of drones for consumers at the time, believed that the quadcopter with its open-source operating software would dominate the aerial photography market. It may have done so, but competition from the China-based Dajiang Innovation Technology Company (DJI) challenged 3DR and outmaneuvered the Berkeley, California, company. In response, 3DR abandoned the drone manufacturing business and DJI came to dominate the hobby market for uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs).

Front view of the "Agras MG-1" Drone with propellers folded to show the radar module, spray tank, spray nozzles, and landing gear, 2016. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF199333

DJI manufactured the Agras MG-1 specifically for the growing market in precision agriculture and advertised the octocopter as “designed for variable rate application of liquid pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides, bringing new levels of efficiency and manageability to agriculture." Farmers found the investment paid off in numerous ways. They reduced input costs by reducing the quantity of synthetic chemicals applied. Additional environmental benefits included reduced run-off that negatively affects water quality and reduced greenhouse gas emissions because farmers used less fossil fuel during application. Reducing vehicular traffic also improved field health by reducing soil compaction which supported regenerative agriculture goals.

The rapid expansion of hobby and commercial drone markets prompted licensing regulation. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) required commercial drone operator licensing in 2016, but some schools had anticipated the need. Northwestern Michigan College first offered a course in Uncrewed Aerial Systems operation at the Yuba Airport in Grand Traverse County, Michigan, in 2010, becoming one of the first schools in the United States to do so. In 2013, NMC launched an Associate in Applied Science degree with a specialization in UAS. Then, NMC purchased one of the first DJI spray drones used in the United States, according to Tony Sauerbrey, UAS program manager at NMC. The Agras MG-1 facilitated the rapid expansion of commercial drone use in Michigan farm fields.

Instruction in Agras MG-1 operation. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF717085

Learning to operate the Agras MG-1, dispensing water, rather than chemicals. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF717084

The Agras MG-1 in flight over a Michigan vineyard. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF717081

DJI designed the Agras MG-1 to carry 22 pounds of liquid pesticides, herbicides, or fertilizers — an amount that could treat an average of an acre in 10 minutes. Its “intelligent” operating system relied on global positioning systems (GPS) data to fly level to the terrain and to automatically adjust the quantity of spray to the flying speed and thus ensure even distribution. Operators had to understand the inputs as well as ways to override them if the battery ran low, the tank ran dry or changes in the weather made it difficult to operate the drone safely.

Rapid expansion in drone-aided agriculture led to training alliances. NMC partnered in 2017 with Michigan State University's Institute of Agricultural Technology so MSU students could meet drone licensing requirements. NMC also partnered in 2020 with Unmanned Systems Institute which administered additional industry safety certifications. Instructors need up-to-date technology, not dated UAS. Thus, NMC retired its Argas M-1, and we acquired it to document early UAS use in precision agriculture.

Debra Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Green Restaurants at The Henry Ford

Stand 44 (left) and Plum Market Kitchen (right) at The Henry Ford / Images courtesy of Debra Reid

The Henry Ford includes five food service locations that have been awarded Green Restaurant Association certification. This certification recognizes excellence in eight environmental impact categories. The Green Restaurant association (GRA) says the standards, "reflect over 30 years of research in the field of restaurants and the environment. Thousands of restaurants and hundreds of thousands of restaurant personnel provide the living laboratory for the continued evolution of the GRA standards. The purpose of the GRA standards is to provide a transparent way to measure each restaurant's environmental accomplishments, while providing a pathway for the next steps they can take to improve their environmental sustainability."

Image courtesy of Green Restaurant Association, dinegreen.com

The Henry Ford's certified food service locations are:

- Stand 44

- Taste of History

- Plum Market Kitchen

- Group Lunch Room B Concessions

- THF Catering

Of note about the The Henry Ford's restaurants and the award scores is that Stand 44 is the only GRA 4 Star certified restaurant in Michigan — the highest rating that you can receive in GRA certification — and one of only twenty in the entire United States. Five of those twenty are in one building on California Polytechnic's San Luis Obispo campus. Three more are dining halls on the campus of Towson University in Maryland.

Stand 44’s waste composting method, which makes use of an industrial biodigester, was a key element of the venue's 4 star GRA certification. / Image by The Henry Ford

Earning these recognitions required cross-functional effort across The Henry Ford. The certification categories focus specifically on energy use, water management, waste management, building & furnishings, chemicals, product sourcing, reusables & disposables, and Education & Transparency. The high points of our efforts to secure Green Restaurant certification include:

- Reducing energy consumption by replacing non-energy-efficient equipment with Energy Star dish washers, ranges, and coolers

- Reducing wastewater contamination by installing oil separators in kitchen drains

- Recycling cardboard

- Recycling glass, plastic, and metals through single-stream recycling

- Recycling scrap metal in conjunction with Facilities & Grounds

- Recycling fresh food scraps to Firestone Farm livestock

- Biodigesting waste and returning it to Greenfield Village fields

- Sourcing green or biodegradable products for food service, including take-out boxes, plasticware, and napkins

- Sourcing fresh foods locally to reduce energy used in processing and transport

- Educating about heritage crops on the menu (in conjunction with Greenfield Village presenters and through presentations to Henry Ford Academy students)

While existing efforts have met green standards for the certification, additional opportunities await future attention. These efforts include composting and biodigesting in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, eliminating single-use plastics, and more robust recycling of aluminum cans and glass bottles. The Henry Ford aims to become the premier example of large institution-wide efforts to achieve environmentally sustainable practices, educating staff, students, and guests about best practices that lessen individual and institutional impact on the environment.

Lee Ward is Director of Food Service and Catering at The Henry Ford.

The Easter Bunny's Origins in America

Spring! A time to celebrate! The season brings longer days, warmer weather, and new life. Budding flowers, baby chicks and lambs, painted eggs, and, of course, the Easter Bunny — all symbolize the return of spring and the end of dreary winter.

Easter Greeting Postcard, circa 1910 / THF113344

The Easter Bunny's ancient origins are unclear, but various cultures have long associated the amazingly reproductive rabbit (or hare) with spring and the celebration of new life. Spring is the time when hares and rabbits — hares are larger and have longer ears and hind feet — produce large litters of leverets (baby hares) or kittens (baby rabbits). This association was a small step toward a connection with spring and Easter, the Christian holiday celebrating the resurrection of Christ.

The Easter Bunny (originally known as the Easter Hare or Easter Rabbit) is believed to have originated in German folklore, which described the mythic creature bringing colorfully decorated eggs to children. Whether the Easter Bunny laid the eggs or hid them may be a matter of interpretation, especially when inquisitive children ask for explanations. Written accounts from Germany in the 1680s mention the Easter egg-laying hare, identified hundreds of years later as the Easter "Bunny." German immigrants brought the tradition to colonial America, perhaps as early as the late 1600s. A drawing by Fraktur artist Johann Conrad Gilbert (1734-1812) depicting a hare hopping along with a basket of decorated eggs provides more substantial proof of the Easter Bunny in early America. Yet, few outside the areas populated by German-speaking immigrants recognized the mythic creature. By the late 1800s, however, the Easter Bunny — like Santa Claus and the Christmas tree — was well on its way to becoming an established holiday symbol throughout America. Growing commercialization of Easter materials — greeting cards, books, toys, candies and sweets, and other material — spread the holiday celebration across cultures, establishing the mythic egg-bringer as a holiday tradition. In the early 1900s, Americans would shed the monikers, Easter Hare or Easter Rabbit, in favor of the more kid-friendly Easter Bunny.

Check out these other Spring and Easter posts found on The Henry Ford's webpages:

Resources used for this article:

- Shoemaker, Alfred L. Eastertide in Pennsylvania, a folk cultural study. Kutztown, PA: Pennsylvania Folklife Society. 1960, pp. 46-50.

- Winick, Stephen. "On the Bunny Trail: In Search of the Easter Bunny." Library of Congress Blogs: Folklife Today. American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project. March 22, 2016.

Andy Stupperich is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

"Long Live" and Prosper: Fandom in Pop Culture

Have you ever decked yourself out in head-to-toe colors of your favorite sports team? Discussed theories about your favorite TV show? Celebrated a fictional holiday like Festivus, wished someone “May the Fourth be with you,” or worn pink on Wednesdays? If so, then you’ve participated in fandom.

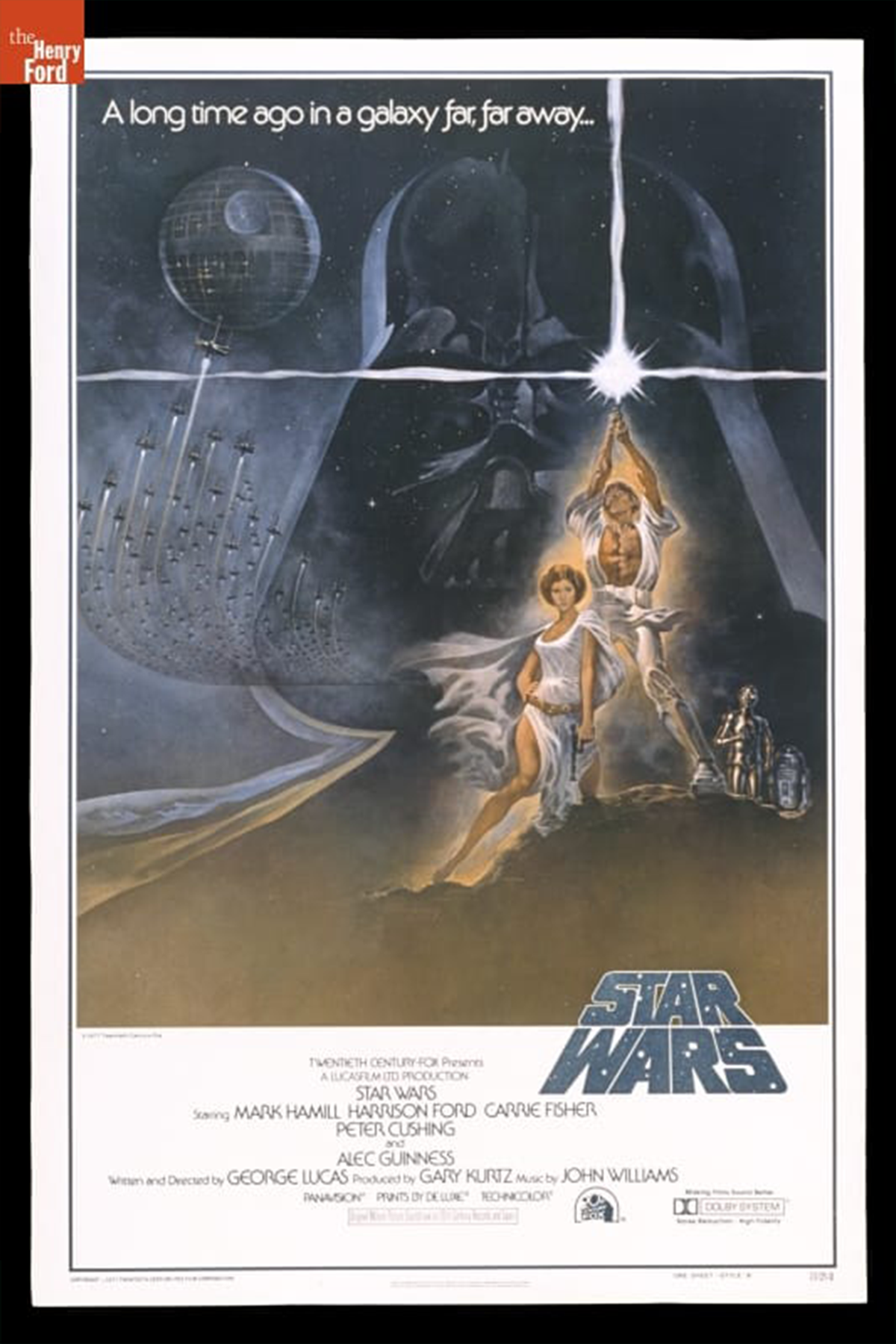

On May 4th of each year, Star Wars fans celebrate Star Wars Day. Once a grassroots, fan-led celebration, it has been embraced by Lucasfilm and Disney and bled over into the popular consciousness. / THF95553

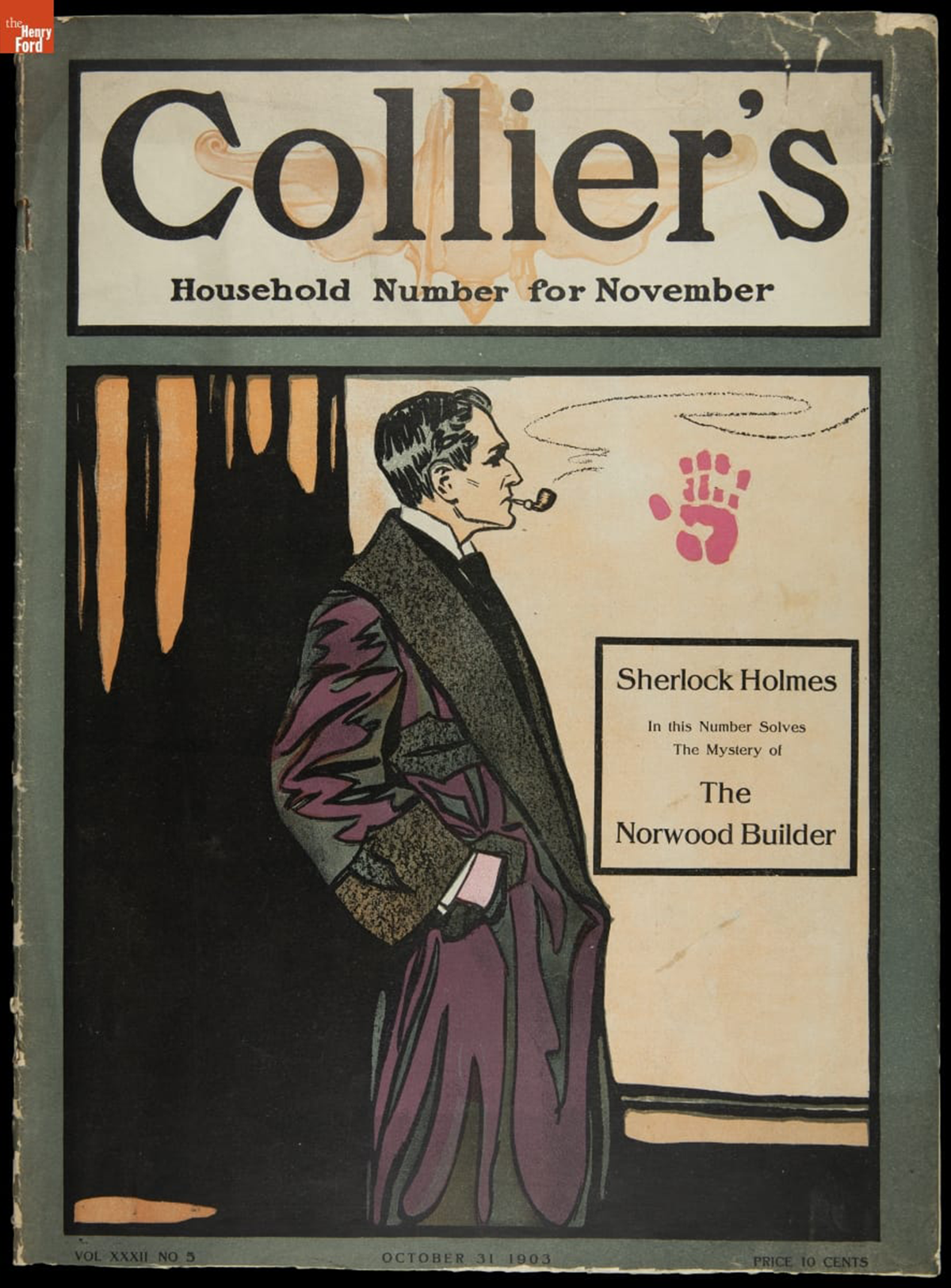

The idea of fandom — a group of fans of something or someone, particularly enthusiastic ones — can trace its roots back to the literature of the 1800s and early 1900s. In 1894, literary scholar and critic George Saintsbury coined the term “Janeites” to refer to the most intense devotees of the work of Jane Austen. In 1903, after receiving numerous letters from the character’s devoted fanbase (and after 20,000 readers cancelled their subscriptions to The Strand, in which his stories were published), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle brought Sherlock Holmes back to life, eight years after killing the character off in hopes of moving on to other projects. Doyle’s “resurrection” of Sherlock Holmes is perhaps one of the earliest examples of fandom shaping the work that it so adores.

Sherlock Holmes’s popularity has lasted well beyond his own “lifetime.” He has been portrayed in film and television over 250 times, and is often treated as a real historic figure, despite his fictional nature. / THF722711

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, fandom communities began to coalesce around the stories published by Hugo Gernsback in Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine. Gernsback published the letters and addresses of fans who sent in mail to the magazine, allowing fans to begin writing to each other, too, meeting up whenever possible. In 1934, Gernsback created the Science Fiction League, a correspondence club for fans of the genre. The Philadelphia Science Fiction Conference was held in 1935, arguably the first of what would become known as “fan cons,” or fan conventions.

Science fiction remained a fertile ground for fandom. In the 1970s, fans of shows like Star Trek began to focus on the relationships between characters, producing creative works like fan fiction and ”fan vids” that explored character dynamics beyond what was presented in the original media. / THF362462

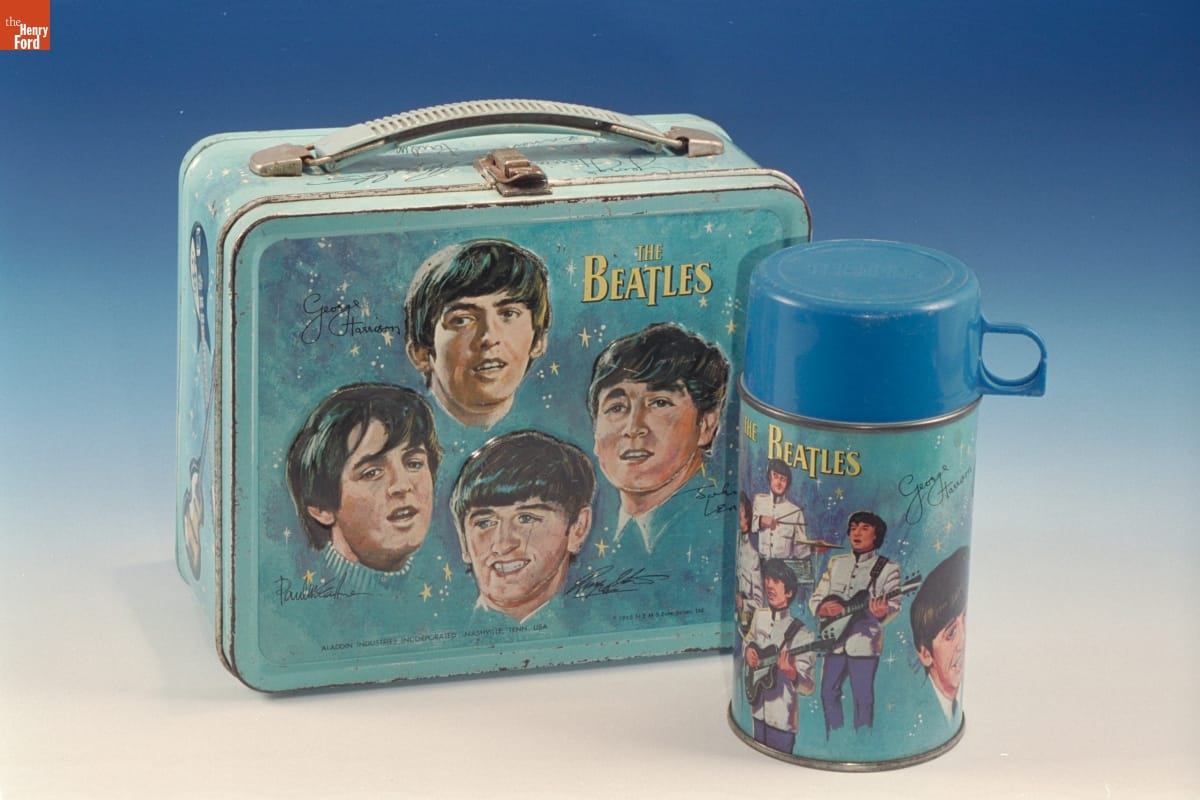

The bar for fandom in music was set by Beatlemania. From 1963 to 1966, young, passionate, female fans of The Beatles created a subculture unlike any the world had previously seen. Originally, Beatlemania was confined to Britain; the phenomenon went international, though, with the band’s appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Everywhere the Beatles went, they were followed by screaming fans, captivated by the band’s memorable hooks, accessible themes, and on-stage charisma. This fervor would last until the group’s last stadium concert in 1966. Beatlemania created the template that later boy bands would seek to imitate, and screaming female fans became a staple of boy band concerts into the 21st century.

At the peak of Beatlemania, there was a plethora of Beatles memorabilia available on the market – whether you wanted to represent the band as a whole, or a particular favorite Beatle. / THF92312

Fandom can be more than just a one-way street. The relationship between Taylor Swift and her fans — dubbed “Swifties” — has changed the face of fandom, both inside and outside of the music industry. Throughout her career, Swift has interacted with her fans on social media, teased upcoming projects with “Easter eggs” for them to decode, and at one point even invited them to “Secret Sessions” — exclusive, invitation-only listening parties where select fans, handpicked by Swift, were the first to hear her soon-to-be-released albums. In return, Swift’s fans have catapulted her to incredible heights of success. The relationship between artist and fandom, however, is not without concern, as Swift herself has alluded to the parasocial extent to which some fans have taken the relationship.

In 2024, Time magazine named Taylor Swift their Person of the Year. The level of fandom surrounding her that year was such that she became what writer Sam Lansky called “the main character of the world." / THF722029

History shows that fandoms have the power to shape popular culture. But why do people join fandoms? The same themes — the feeling of acceptance, understanding — crop up in many discussions around the question. So, too, does the topic of escapism — using another world, or even another person, as a distraction from the stress of one’s own life. It is part of human nature to seek inclusion and comfort, to feel as if we belong as part of a group, that we have found a safe space. Perhaps this, then, is the role that fandoms fill, and why they remain a recurring part of our stories.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

A Symbol of Courage

The Jackson House: a Curated Story from Selma, Alabama, to Greenfield Village

At the end of last summer, the story of the Jackson House, a landmark symbol of the Long Civil Rights Movement, took a historic turn. On Maple Lane in Greenfield Village, initial repositioning of the more than 100-year-old structure began, marking the next chapter in a meticulous reconstruction project. With its relocation from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan, the Jackson House is set to give millions of visitors to The Henry Ford the opportunity to hear stories of family, friendship, leadership and Selma’s role in one of the most momentous movements in U.S. history — the organized 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches that helped ensure all Americans would have the civil rights and voting rights promised to them.

Photo by Brian Egen

It was Dr. Sullivan Jackson and Mrs. Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson who opened their Selma home to close friend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his allies in Dallas County and nationally as a place to rest and strategize the path forward to secure voting rights for African Americans. Hundreds of people came through the home, including several Nobel Peace Prize winners, international dignitaries, media representatives, and activists and supporters of civil rights for all. This activism helped lead to the passing of the Voting Rights Act in June 1965.

Much work still needs to be done in the home’s reconstruction in Greenfield Village, which first required preparing the site between the George Washington Carver Memorial and the William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace. Last fall, further reassembling of the house’s structural components, such as its covered front porch, commenced. Over the coming months, the roof will be replaced, floors and walls repaired, electrical and plumbing systems connected, central heating and air-conditioning will be installed, and fire protection and security systems will be added.

Less visible, yet just as critical, behind-the-scenes work also continues, said Amber N. Mitchell, The Henry Ford’s curator of Black history. “The home will look much different than what it appeared in Selma before the relocation,” she said. “We are renovating it to look similar to what it did around 1965, and there are many ways to interpret that time period that we are investigating.

“This is a true collaboration,” she added. “A combination of the actual structure reconstruction, our historical resources and great detective work on the part of our curatorial team and staff to ensure the Jackson House’s story of family and community is as uplifted as the connecting story of the voting rights movement.”

A public opening of the restored Jackson House in Greenfield Village is currently planned for June 2026.

This post was written by Jennifer LaForce and adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.