Getting into the Air: Alexander Graham Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association

Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922) is best remembered for his work to develop the telephone, but he had a pioneering role in aviation as well. In 1907, Bell assembled a small team to design, build, and pilot some of the earliest flying machines. Working together at the dawn of manned flight, the members of Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association made extraordinary developments in a remarkably brief period of time.

Founding the Aerial Experiment Association

As his 60th birthday approached, Alexander Graham Bell finally had the time and means to pursue his long-time interest in solving the problem of flight. Bell had supported and closely followed the failed efforts of Samuel Langley to develop a practical flying machine beginning in the 1890s. He also knew of Wilbur and Orville Wright’s successful 1903 flight. The Wrights were working in secret, refusing to collaborate with could-be competitors as they shopped their Flyer around to potential buyers in the United States as well as Europe—where other aeronautical pioneers were making progress with flying machines of their own design.

Bell believed tetrahedrons—triangular pyramids—held the answer. Convinced a practical flying machine could be produced by motorizing a tetrahedral kite, he began a series of experiments at Beinn Bhreagh, a summer estate owned by Bell and his wife Mabel, overlooking Bras d'Or Lake on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. As his investigations progressed, Bell decided to assemble a team of talented young enthusiasts to help bring them to completion.

Aerial Experiment Association Members Thomas Selfridge and Alexander Graham Bell, 1908. / THF285504

The Bells warmly welcomed these four recruits to Beinn Bhreagh in the fall of 1907, and all reached an agreement to form the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA):

- J. A. D. McCurdy (1886–1961), Treasurer—The son of Bell’s secretary, this Cape Breton Island native and University of Toronto student became fascinated by the tetrahedral kite experiments at Beinn Bhreagh during a visit home. Bell recruited McCurdy to assist.

- F. W. “Casey” Baldwin (1882–1948), Chief Engineer—A recent mechanical engineering graduate from Toronto, Baldwin visited Beinn Bhreagh with McCurdy, a college friend. Bell appreciated Baldwin’s enthusiastic interest in his tetrahedral kite projects and invited him to take part.

- Glenn Curtiss (1878–1930), Director of Experiments—Known for building lightweight, powerful engines, Curtiss manufactured motorcycles in Hammondsport, New York. Bell purchased his first aeronautical engine from Curtiss and, considering him to be the preeminent motor expert in the United States, persuaded him to formally participate in the experiments at Beinn Bhreagh.

- Thomas Selfridge (1882–1908), Secretary—A promising U.S. Army lieutenant assigned to the Signal Corps’ newly established Aeronautical Division, Selfridge saw a future in military aviation and asked to observe Bell’s kite experiments. Immediately impressed, Bell petitioned his friend President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of War William Howard Taft to allow Selfridge special permission to join the Aerial Experiment Association.

The members agreed to work together over the course of one year, effective October 1. Mabel Bell (1867–1923) supported the venture from its beginning, providing the starting capital. With the understanding that experiments would soon move to a warmer location, Beinn Bhreagh served as Aerial Experiment Association headquarters.

The Aerial Experiment Association’s articles of agreement outlined some financial details: McCurdy and Baldwin would earn $1,000 and Curtiss $5,000—an acknowledgment of his special expertise and compensation for time away from his manufacturing company. Bell and Selfridge declined a salary. Each member would receive a share of any profit from the group’s experiments. But these specifics were ancillary. The Aerial Experiment Association’s primary objective was clear: “to get into the air.”

Experiments of the Aerial Experiment Association

The group agreed to begin formal experimentation with Bell’s tetrahedral kite, Cygnet, and then move on to build and test “aerodromes” (Bell’s preferred term for what would come be to be called “airplanes”) designed by each of the other members.

| Cygnet |

| tested as a glider on Bras d'Or Lake, Cape Breton Island, December 6, 1907 |

| Nearly 3,400 “tetrahedral cells” constructed of aluminum and red silk formed Bell’s massive kite. Though it was built to be motorized, Bell wanted to first test the Cygnet as a glider. Towed by boat, with Selfridge aboard, the delicate craft remained aloft for seven minutes before coming down and being pulled into the water. The Cygnet was a total loss, but “Bell’s Boys,” as they became known, were satisfied with the results. |

Bell planned to continue tetrahedral kite experimentation after the Cygnet test, but as agreed, the Aerial Experiment Association would first begin work on aerodromes. After Christmas 1907, everyone relocated to Hammondsport, New York, for milder weather and access to the facilities of the Curtiss Manufacturing Company. Excitement about the arrival of a famous inventor rippled through town, and Bell’s Boys quickly became the stars of Hammondsport’s social scene. The younger men enjoyed easy access to Curtiss motorcycles by day, and evening discussions about how best to tackle the problem of flight—often held in a room of the Curtiss home they dubbed the “thinkorium”—deepened the group’s bond.

Because Selfridge had piloted the Cygnet, his aerodrome design would be built next. Though the members of the Aerial Experiment Association—especially Selfridge—had studied contemporary advances in aviation, none had seen an airplane. After weeks of glider practice and careful construction at Hammondsport, the Aerial Experiment Association was ready to test its first one—the Red Wing.

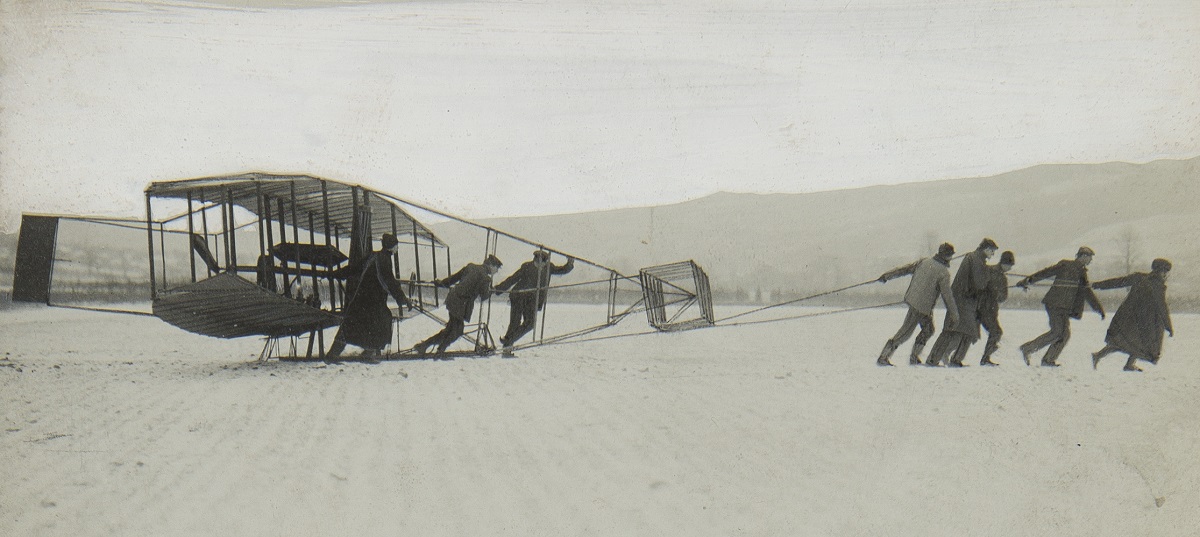

Before the first flight of the Red Wing, 1908 / THF265979

| Red Wing |

| first flown on Keuka Lake, Hammondsport, March 12, 1908 |

| The Aerial Experiment Association suppressed expectations for the Red Wing—named for the red silk fabric of its curved wings (left over from the Cygnet). The group recognized the fixed-rudder craft as a first attempt. To everyone’s surprise, the Red Wing, piloted by Baldwin, took off on the first attempt and flew more than 300 feet before coming down. |

As pilot of the Red Wing, Baldwin was selected to design the Aerial Experiment Association’s second aerodrome. He decided to partner with Curtiss. The men incorporated findings from the Red Wing experiment into their improved design for the White Wing.

| White Wing |

| first flown at Hammondsport, May 18, 1908 |

| The much improved (though less colorful, with varnished muslin wings) White Wing featured a front elevator and rudder controlled by a steering wheel, moveable wingtips adjusted by wires attached to the pilot for lateral control, and wheels instead of skids. Baldwin piloted White Wing first, lifting off for a 93-yard jump. Curtiss took his turn on May 21, covering 339 yards in two jumps—the longest public flight in the United States to date. |

Though the weather had warmed, excitement over the Aerial Experiment Association’s quick progress led the group to stay in Hammondsport to begin building a third aerodrome, the June Bug, designed by Curtiss.

| June Bug |

| first flown at Hammondsport, June 21, 1908 |

| Seemingly small improvements to the White Wing’s design made the June Bug—named by Bell for the beetles flying around Hammondsport that time of year—faster and more responsive. Curtiss adjusted the length and placement of various components and incorporated a shoulder yoke that allowed the pilot to control the June Bug’s larger, longer wingtips. Its muslin wings were coated in a yellow-colored mixture of turpentine, paraffin, and gasoline called “dope.” Beginning on June 21, Curtiss made several flights that were so successful the Aerial Experiment Association decided to enter the June Bug into competition. |

The 1908 Scientific American aviation trophy recognized the first airplane to cover one straight kilometer in an official trial. On July 4, Curtiss and the June Bug wowed a huge crowd with a winning flight of 5,360 feet (1.6 kilometers).

Glenn Curtiss piloting the June Bug, 1908. / THF289064, detail

The June Bug’s success marked a turning point for the Aerial Experiment Association. Bell and Baldwin returned to Cape Breton Island to work on another tetrahedral kite, the Cygnet II. McCurdy and Selfridge remained with Curtiss in Hammondsport to begin building the Aerial Experiment Association’s fourth aerodrome, the Silver Dart. McCurdy’s design, the Silver Dart was intended to be a final improvement on the June Bug. At the end of August, Selfridge was called away and assigned to the commission overseeing U.S. Army trials of the Wright Flyer at Fort Myer, Virginia.

The future of the Aerial Experiment Association, which had achieved its primary goal and was set to expire on September 30, was under discussion when tragedy struck. Selfridge, riding as Orville Wright’s passenger during a trial flight on September 17, was killed—the first fatality from an airplane crash.

The remaining members of the Aerial Experiment Association convened on September 26 and voted in favor of a six-month continuance (with further funding promised by Mabel Bell). While Bell and Baldwin continued work at Beinn Bhreagh, Curtiss and McCurdy forged ahead in Hammondsport. (Incidentally, experiments in both locations to develop aircraft that could take off from the water during this time—including outfitting the June Bug with pontoons to create the Loon—were unsuccessful.) Satisfied with the Silver Dart’s progress, Curtiss and McCurdy disassembled it for shipment to Cape Breton Island and headed to Beinn Bhreagh in late January 1909. The following month, attempts to lift the Cygnet II from the ice on Bras d'Or Lake failed, but the Silver Dart made history.

| Silver Dart |

| first flown at Bras d'Or Lake, Cape Breton Island, February 23, 1909 |

| The Silver Dart—with rubberized (or “silvered”) silk wings—featured a major departure from the Aerial Experiment Association’s earlier aerodromes: a water-cooled (vs. air-cooled) engine to prevent overheating and allow for longer flights. Other adjustments included the omission of a tail and lengthening of the front elevator and wingtips. McCurdy piloted the Silver Dart’s maiden run, stunning the crowd that had gathered to view the first successful heavier-than-air flight in Canada. |

The Silver Dart, Hammondsport, December 1908. / THF289114, detail

Even before that winter, Curtiss had begun to drift from the Aerial Experiment Association toward his own aviation projects. On March 31, 1909, a year and a half after forming the Aerial Experiment Association, Bell and his recruits somberly agreed to dissolve. Bell wrote a farewell to the Aerial Experiment Association, wishing “every success to the commercial organization that will succeed it, and to the individual members of the Association in their future careers.” He rightly declared that the Aerial Experiment Association “has made its mark upon the history of aviation and its work will live.”

Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- 1925 Fokker F.VII Tri-Motor Airplane, "Josephine Ford," Flown Over the North Pole by Richard Byrd

- A Closer Look: Air Traffic Control Radar Scope

- Make a Paper Airplane: Make, Build, Engineer

- Neil Armstrong: Reluctant Hero

20th century, 1900s, Canada, flying, by Saige Jedele, aviators, airplanes

Facebook Comments