Mary Judge’s Big Break: Central Market Through the Eyes of One Head-Turning Market Character

| Written by | Ayana Curran Howes |

|---|---|

| Published | 7/13/2021 |

Mary Judge’s Big Break: Central Market Through the Eyes of One Head-Turning Market Character

| Written by | Ayana Curran Howes |

|---|---|

| Published | 7/13/2021 |

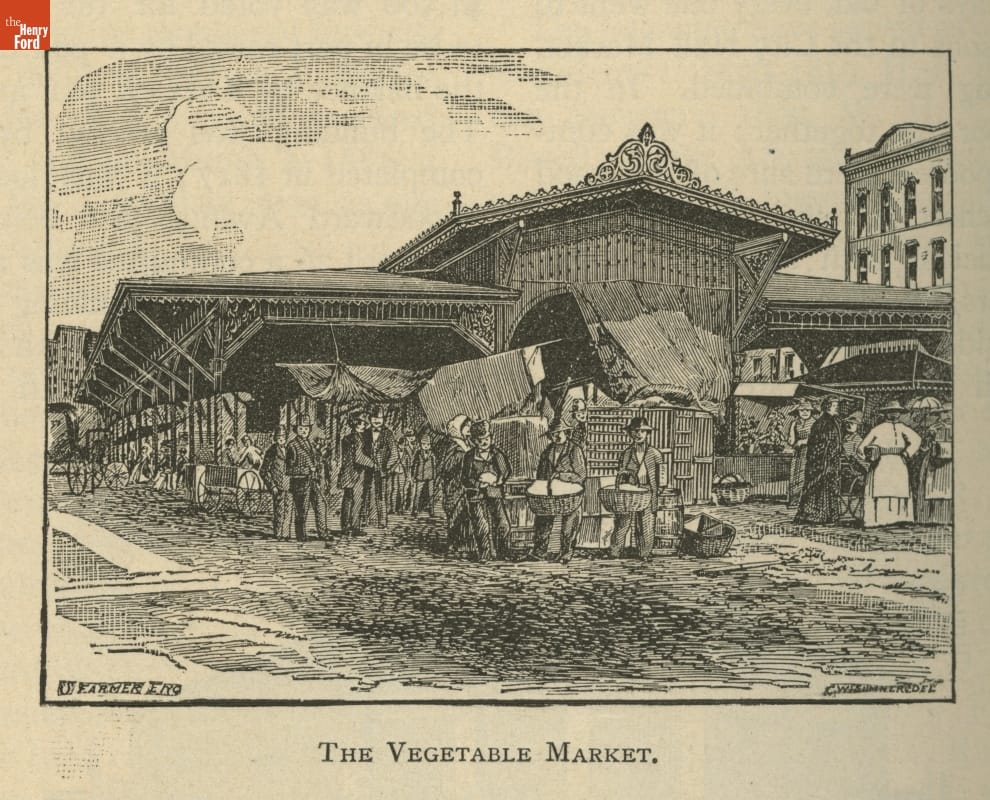

"History of Detroit and Michigan," Silas Farmer, 1884, page 794 / THF139107

Fresh food markets have always brought communities of all backgrounds together for nutritional and social sustenance. The markets of the 19th century were different than today’s in terms of sanitation, regulations, and petty crimes, but the desire for community that existed then remains true. Today, Detroit’s Eastern Market and dozens of other markets in southeast Michigan provide citizens with food security and support a burgeoning urban agricultural movement and the local economy.

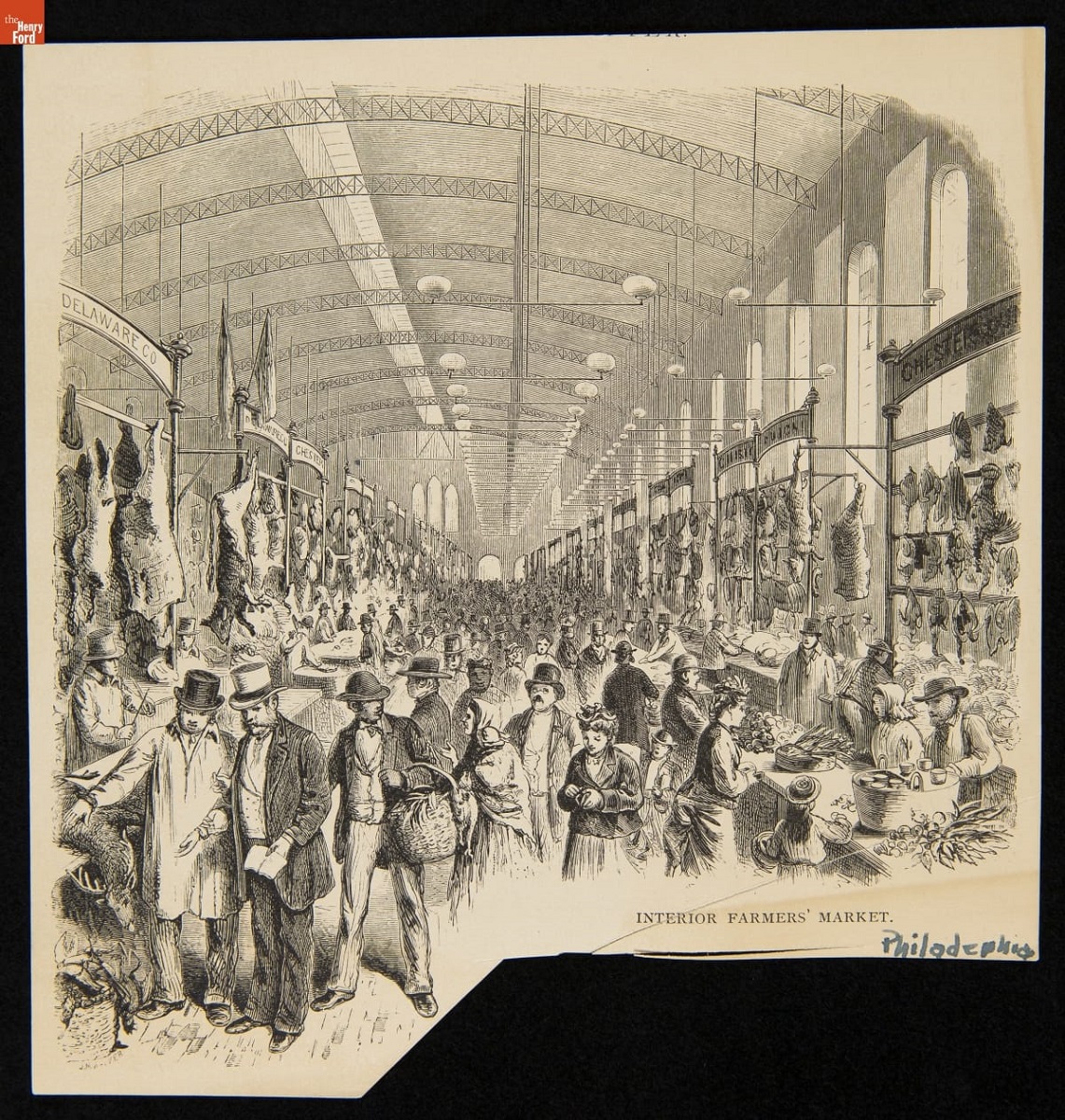

Interior of a farmers’ market, 1875, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Originally published in Earl Shinn, A Century After: Picturesque Glimpses of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania (published in Philadelphia by Lane Allen & Scott and J.W. Lauderbach, 1875), pg. 156, on the title page of the chapter "Marketry.” This illustrates what we can imagine the inside of Central Market looked like on a busy market day. / THF610498

The Vegetable Building (now being reconstructed in Greenfield Village) opened in Detroit's public market, then known as City Hall Market, in 1861. It remained a hub of community cohesion and commercial competition for 30 years until the city closed it, later dismantling it and relocating it to Belle Isle in 1894. In the three decades that the Vegetable Building attracted vendors and customers, Detroit’s population grew from 45,619 to 205,876 (per Detroit Historical Society) and the market tried to keep pace.

Mounting calls for the demolition of Detroit’s rat-infested “eyesore” resulted in the obliteration of the three-story “Central Market” brick building that housed butchers and market administrators between 1880 and 1894. It also prompted removal of the Vegetable Building to Belle Isle, and its replacement with a retail park (Cadillac Square) and a new public market (Eastern Market). This process destroyed the public market in central Detroit, but ultimately preserved the market’s Vegetable Building.

The Henry Ford acquired the Vegetable Building in 2003. After its reconstruction, the Central Market’s Vegetable Building will allow us to tell the stories of the vendors and consumers that frequented the market. These stories will illustrate that Central Market was a place where Detroiters came to purchase food stuffs, where entrepreneurs (many of them immigrants) were able to make a living, and where vibrant community life (including competition and discrimination) played out.

This year, we’ve been working to establish authentic stories as the basis for living history programming at the Vegetable Building, featuring costumed presenters and dramatic performances. Additional research underscores decisions about modern-day vendors invited to sell their honey, bread, pickles, eggs, flowers, and fresh fruits and vegetables to visitors at weekly markets and specialty markets in Greenfield Village.

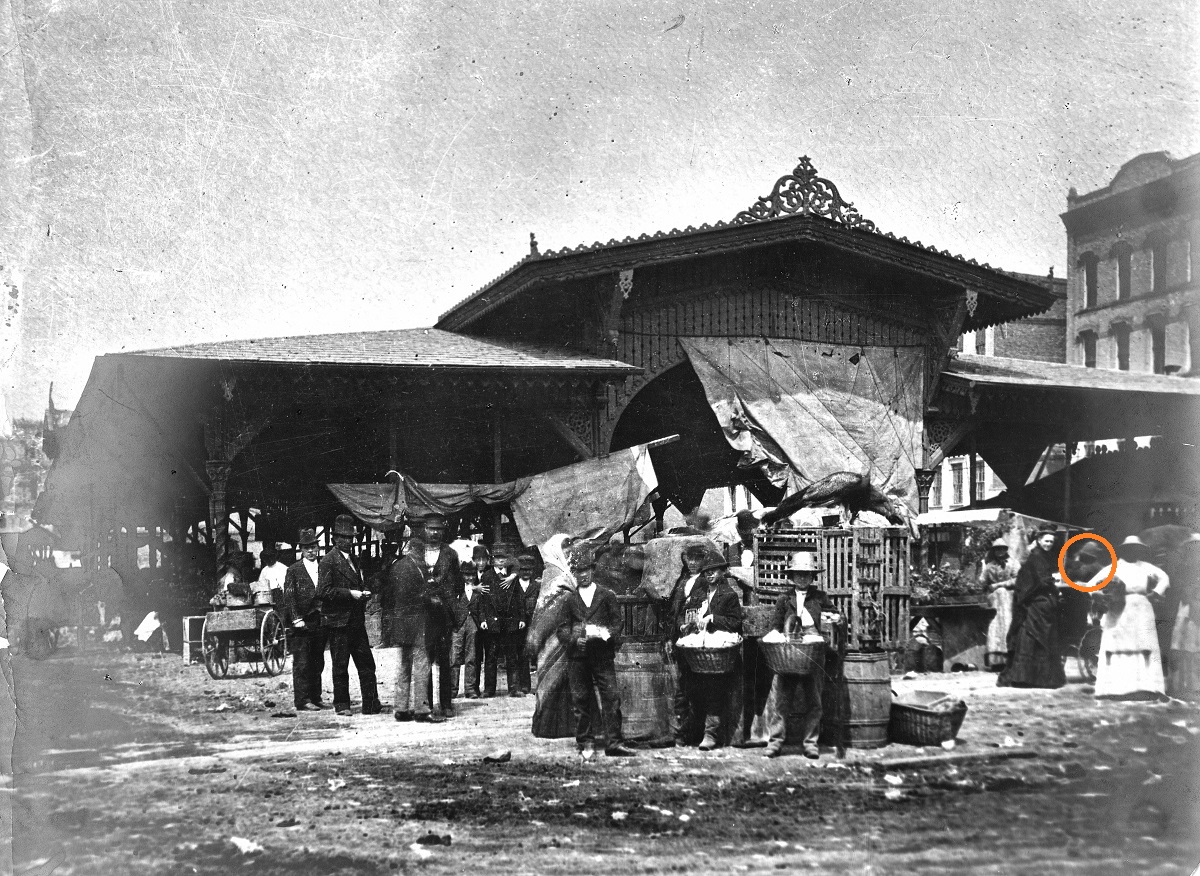

Group of women, one with a baby carriage, in front of the Central Market Building, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1890. / THF623829

A partnership between The Henry Ford and the University of Michigan Museum Studies Program resulted in a script for a dramatic presentation that will help guests grasp the numerous ways that the market building affected urban life. Four students from the Museum Studies Program—Kathleen Brown (American Culture), Laurel Fricker (Classical Art and Archeology), Antonello Mastronardi (Classics), and myself, Ayana Curran-Howes (Environment & Sustainability)—crafted a script for a noteworthy Central Market character. The market was filled with characters, but one that captured the attention of newspaper reporters, the police, and a fair number of male suitors was Mary Judge. She became the focus of our investigation.

Our research into Mary Judge unveiled a fascinating and difficult, yet vibrant, individual. Newspaper reports documented her wit, sharp tongue, charm, and self-awareness as a woman staking her claim to independence. Newspaper reports from the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press gave us a foundation on which to build a script for an entertaining and educational performance.

Vegetable Shed at Detroit’s City Hall Market, known as Central Market after 1880. It is identified as “Cadillac Square Market (Detroit, Mich.)” in the George Washington Merrill photographs collection, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library (BL003974). The original was one of two photographic images likely taken by James A. Jenney for A. J. Brow, Detroit, Michigan, and published as a stereograph. The original stereograph is in the Burton Collection, Detroit Public Library. We believe the woman circled in orange may be Mary Judge, vending flowers.

The script, featuring Mary Judge, is set during a Saturday night market in the 1880s. We chose a Saturday night market to introduce guests to the hustle and bustle of market life that everyday Detroit residents experienced. Farmers saved their best produce for busy Saturday nights when throngs of factory workers and working-class citizens came to purchase fresh produce and meat, as well as to socialize.

Mary Judge enters as a whirlwind. Her livelihood depended on capturing the public’s attention, and the dramatic presentation conveys that urgency. Mary also conveys the tumultuous yet essential relationship that hucksters like herself had with the farmers who grew the products that hucksters resold. Mary’s success at reselling depended on the relationships she cultivated with other vendors and the larger market community. The eight-minute solo act features Mary’s opinions about the role of the market in Detroit life, before the politics around the closing of the market disrupted Mary’s status quo starting in 1891.

What did Mary resell? The Michigan climate lent itself to a wide array of produce. Consumers could choose between market crops such as strawberries and cherries, often eaten to the point of bellyache (Detroit Free Press, June 25, 1874), or other seasonal crops such as rhubarb, cucumbers, and celery worthy of larceny (Detroit Free Press, August 12, 1879). Mary herself sold many different things, including coffee, flowers, fruit, poultry, and “fried cakes, gingerbread, pig's feet” (November 22, 1875). The Free Press reported her doughnuts “were very fillin’ for the price” (February 28, 1876).

Cherries. Nurseryman's Specimen Book, 1871-1888, page 48. / THF620211

Additional carnival-like attractions included strong-man machines, magic tricks, and exotic pets for sale. The variety of attractions created a bustling crowd that made it “often a feat to swallow a cup of coffee, without having it spilled” (Detroit Free Press, December 19, 1869).

The research plan we devised included numerous stages.

We reviewed other dramatic performances at The Henry Ford, including “The Disagreeable Customer” at J.R. Jones General Store and “How I Got Over” at Susquehanna Plantation. We also reviewed expert advice about living history programming collected in the Living History Anthology (Katz-Hyman et al., 2018). These informed the structure and style of our script.

Then, we asked ourselves “What was the social and economic function of the market? Who was allowed to keep a stall in the market and in what ways were they restricted, supported, and able to survive in this market economy?” Answers to these questions were revealed through secondary sources including Gloria Main, “Women on the Edge: Life at Street Level in the Early Republic” (2012); Jen Manion, “Dangerous Publics,” in Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (2015); and Melanie Archer, “Self-Employment and Occupational Structure in an Industrializing City: Detroit, 1880” (1991).

We also looked at Detroit’s demographic data to understand the composition of the consumers in the market space. Then we conducted primary research, reviewing news reports published in the Detroit Free Press and the Detroit News that featured Mary Judge over 30 years. These conveyed the verbiage of the time, the historic perspective on events, the politics of the past, and the atmosphere of the market. The newspaper coverage of the market generated a body of evidence that continues to inform us.

From left to right: Ayana Curran-Howes, The Henry Ford’s Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid, and Antonello Mastronardi, looking at the site where the Vegetable Building is being reconstructed in Greenfield Village, March 6, 2021. Photo taken by Laurel Fricker.

The low capital investment required to become a huckster allowed some immigrants to Detroit, including Mary Judge, to carve out a space in the public market. Other immigrants, including English and Irish individuals as well as Germans, Poles, and Italians, gained a toehold on economic independence. German butchers dominated the fresh- and processed-meat markets. They had more capital and political influence and, therefore, access to better stalls. In contrast, the Italians, newcomers during the 1880s, tried their hand at selling fruit.

Long before these European ethnic groups arrived, Black Detroiters faced racism in the marketplace and endured discrimination and violence. Nonetheless, they used the marketplace, as did other entrepreneurs, to sell their labor as chimney sweeps and whitewashers (those who painted cellars and building interiors, even the Vegetable Building interior, to intensify natural light).

The portrayal of Mary Judge will show guests how women used huckstering to gain financial independence. This was one of few alternatives for single women at the time, other than domestic service. Secondary readings and primary evidence indicated that women rarely held public-facing positions comparable to that of Mary Judge, the Central Market huckster. When they did, they were harassed by men and police alike. The consequences compounded for poor unmarried women, identified as “unladylike” in demeanor, and disruptive in action.

Hierarchies based on privilege kept many vendors marginalized. Female and immigrant vendors had to overcome language barriers, and had to navigate racism, sexism, and xenophobia when they tried to obtain permits, rent a stall, and obtain goods to sell. As an example, anti-immigrant sentiment followed Italian fruit vendors wherever they went. Mary Judge perpetrated this herself, verbally engaging with Italians and decrying their business decisions: “Go an’ absolve yerself of your business, sir; an’ not be hawkin’ ye’r truck on the streets this blessid day [Sunday]” (Detroit Free Press, July 25, 1887).

From left to right: Debra Reid, Kathleen Brown, Ayana Curran-Howes, Laurel Fricker, Antonello Mastronardi, and The Henry Ford’s Director of Greenfield Village Jim Johnson, standing outside the fenced off area where the Vegetable Building was being erected, March 6, 2021. Photo taken by Jeanine Head Miller.

All vendors faced other societal pressures. One of the most pernicious threats, petty theft perpetrated by those “sampling” products, undermined market vendors. Mary turned to market administrators to mediate her grievances, as did other vendors. She also reported abuses to the police, who intervened in some situations.

Despite these barriers, hucksters made this their way of life and stayed in the market for decades. Mary Judge, a twice-married devout Catholic, was as durable a huckster as one could be. She kept a stall from 1863 until city officials dismantled the market in 1894.

Starting in Spring 2022, you will be able to visit the Vegetable Building in Greenfield Village, and soon you'll be able to meet the “queen of the market,” Mary Judge, selling coffee and decades of wisdom as a huckster from her stall. This coming-soon one-woman show (as Mary would have preferred it) will illustrate huckstering as an occupation and as a way of life.

Thanks to the following people for research support and guidance during the Winter 2021 term:

- Gil Gallagher, curatorial research assistant volunteer, The Henry Ford

- Jim Johnson, Director of Greenfield Village and Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes, The Henry Ford

- Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life, The Henry Ford

- Patricia Montmurri, author/journalist, Detroit Free Press

- Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment, The Henry Ford

- Susan Whitall, author/journalist, Detroit News

Ayana Curran-Howes is 2021 Simmons Intern at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Series | |

Themes |