A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama

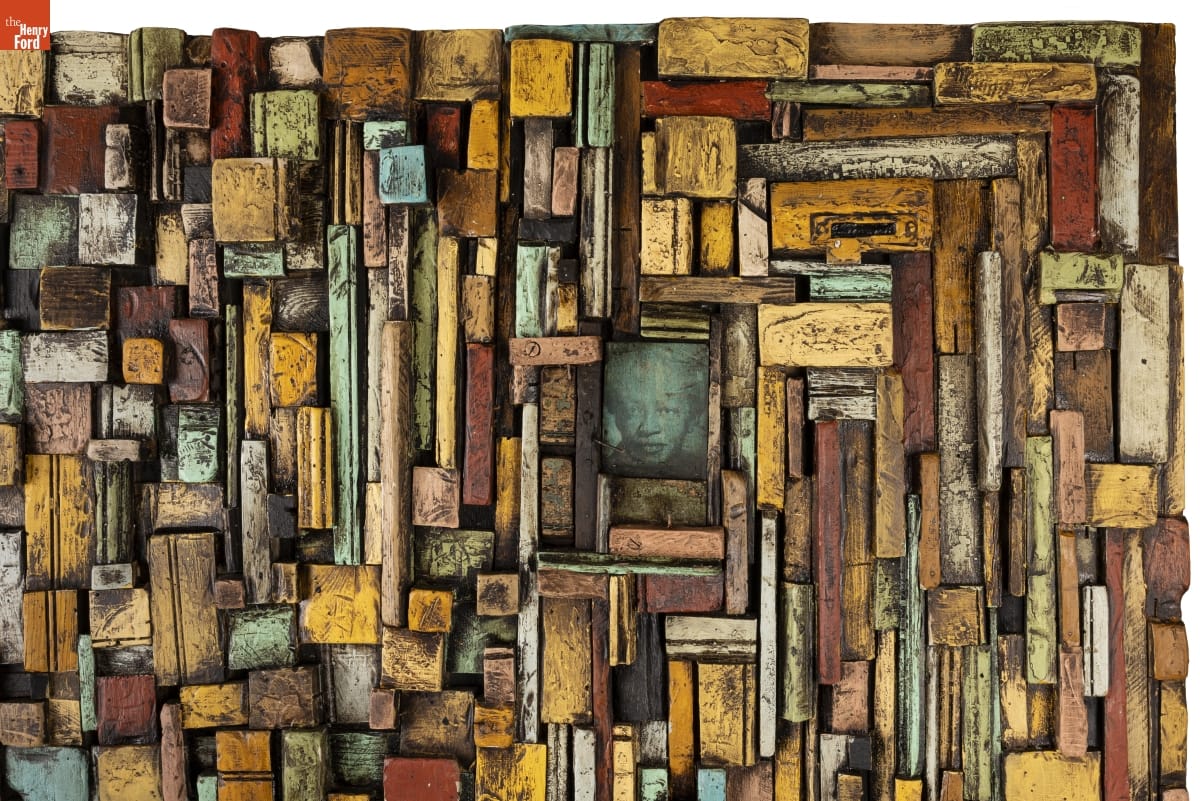

In 2023, The Henry Ford acquired an incredible piece of art: a wooden sculpture by New Orleans artist Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, entitled “A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama.” The wooden quilt weaves together many threads from both St. Jacques's own family history and the stories already told in the institution's collections.

"A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama" by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, 2023 / THF197819

"A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama" by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, 2023 / THF197819

Jean-Marcel St. Jacques is a twelfth-generation Louisiana Afro-Creole. In the 1970s, his family left Louisiana for California, hoping to escape the racial oppression they faced in the South. Looking to reconnect with his family's roots, in 2004, St. Jacques moved back to the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, purchasing a former boarding house that had been owned by a woman known to the community as Mother Sister. One year later, however, Hurricane Katrina ravaged the Gulf Coast, particularly New Orleans. St. Jacques's home, along with many others, was severely damaged.

St. Jacques describes how the storm became a defining moment in his life, writing: “The last decade and a half of my life and work has been defined by the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The force of nature that blew the roof off of my house and forced me into a silent meditation and communication with my ancestors.” Using wood and other architectural fragments he salvaged after the disaster, St. Jacques began creating sculptural wooden art pieces -- doors, wall hangings, and his larger “quilts” — piecing together fragments and hardware, adding vibrant colors, and weaving in references to his family history. His great-grandmother Laura Agnew had been a quiltmaker, while his great-grandfather had been a junk man, gathering and reselling pieces he found, as well as a hoodoo man, practicing syncretic spirit work. St. Jacques considers his workshop to be “an ancestor shrine,” and keeps his great-grandmother's quilts and great-grandfather's tools nearby as he works.

Detail from "A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama,'' featuring a portrait of Laura Agnew, the artist's great-grandmother / THF197824

Detail from "A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama,'' featuring a portrait of Laura Agnew, the artist's great-grandmother / THF197824

While every one of his pieces honors his family history, St. Jacques wanted this piece to be a special tribute to his great-grandmother, whom he called “Big Mama.” Amongst the hardware and painted wood blocks that make up the piece, there is a printed portrait of her tucked in the upper right-hand quadrant.

St. Jacques's wooden quilt not only connects to his great-grandmother's quilting practice, but to the practice of other quilters already represented in The Henry Ford's collections — particularly the work of quiltmaker Susana Allen Hunter.

Susana Hunter lived in Wilcox County, an impoverished, rural area of Alabama. She was an improvisational quilter, making up her quilt designs as she went along, often using material taken from clothing and fabric she and her family used, as well as material given to her by others. The quilt below features fabric that likely came from the clothing her husband Julius wore as a tenant farmer — denim overalls and flannel shirts — and is backed with material from mule feed sacks. The quilt not only reflects Hunter's improvisation and creativity, but also captures the history of her family through the physical material — much like St. Jacques's wooden quilt.

Strip Quilt Made of Work Clothes by Susana Allen Hunter, 1965-1970 / THF73636

Strip Quilt Made of Work Clothes by Susana Allen Hunter, 1965-1970 / THF73636

Acquiring this wooden quilt continues The Henry Ford's long tradition of collecting American folk art. Henry Ford's personal interest in what we would today consider folk art created the foundation for a collection that now stands at nearly 2,000 pieces, and includes works by such noted artists as George Washington Mark (1795-1879), Ammi Phillips (1788-1865), and William Matthew Prior (1806-1873). St. Jacques's work further enriches this collection, updating and diversifying it in a way that honors the folk art tradition.

"Opening the Door," considered painter George Washington Mark's masterpiece, is one of the highlights of The Henry Ford's folk art collection. / THF172048

"Opening the Door," considered painter George Washington Mark's masterpiece, is one of the highlights of The Henry Ford's folk art collection. / THF172048

Every object in The Henry Ford's collection tells a story about past lives, be it directly via pieces connected to specific individuals, or more generally with objects that demonstrate life in different time periods. It is a special honor to be the institutional home for a piece like “A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama” — a piece that honors the life of the artist, his family, and his community — and to share with the public the rich stories it holds.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.

Clara Ford’s Travel Diaries

When traveling today, it is easy to document our journey through swift clicks of our phones and cameras. The people, sights, and sounds of a moment are captured and recorded through photos, videos, and social media posts making it easy to reflect on where we were and what we enjoyed.

The desire to document a memorable trip has remained a common tradition and in the age of Clara Ford, was accomplished through travel journals or diaries. Even with the advent of photography, film had to be thoughtfully allocated to document the most meaningful memories from a trip.

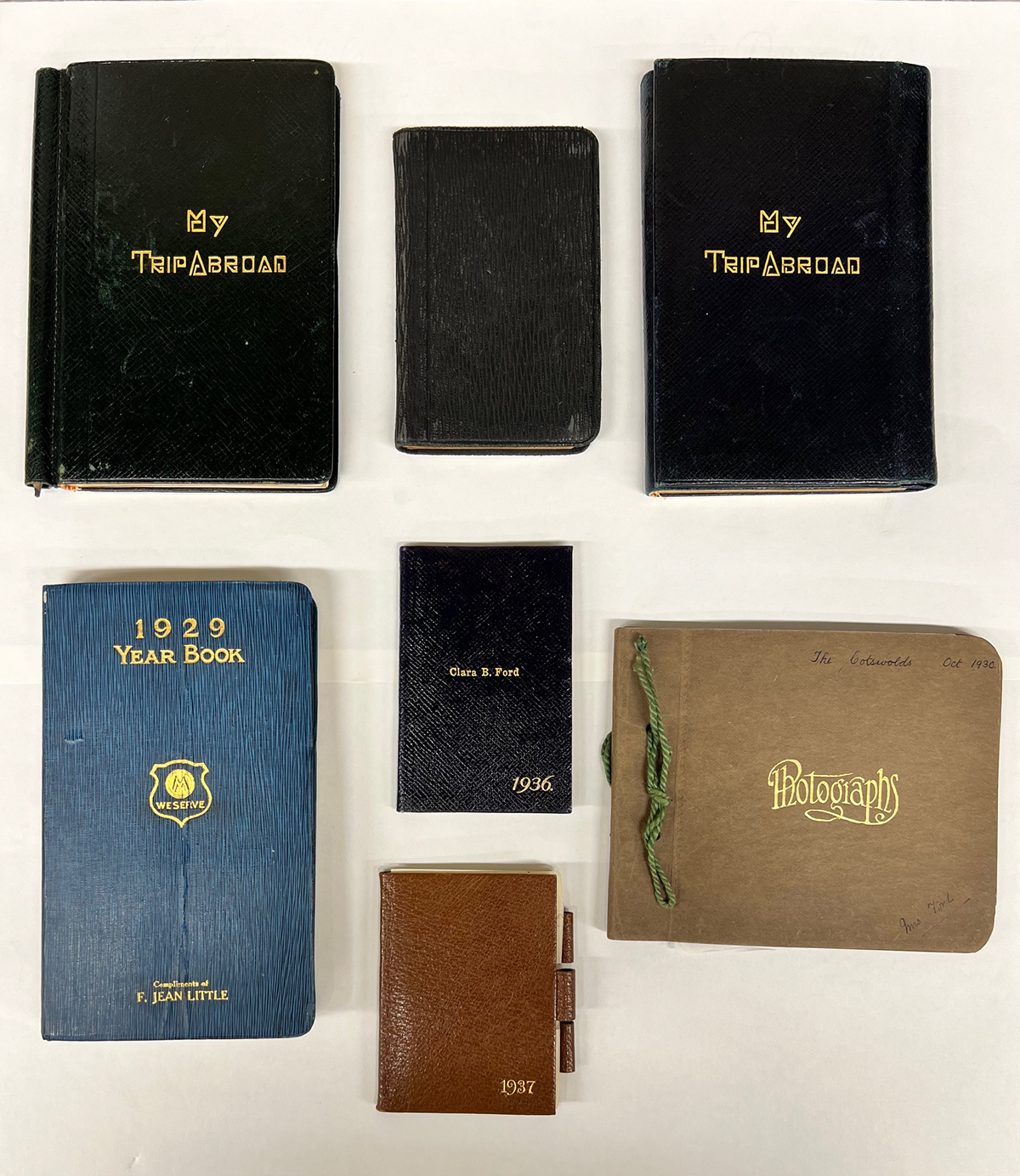

The Henry Ford's collections include several travel diaries written by Clara Ford dating from 1912 to 1945. Clara did not keep a diary for every trip she took. As the wife of Henry Ford, her travels were frequent and varied. Most of the diaries document her travels overseas, a momentous journey for anyone at that time, and winter retreats to Richmond Hill, Georgia, and Fort Meyers, Florida.

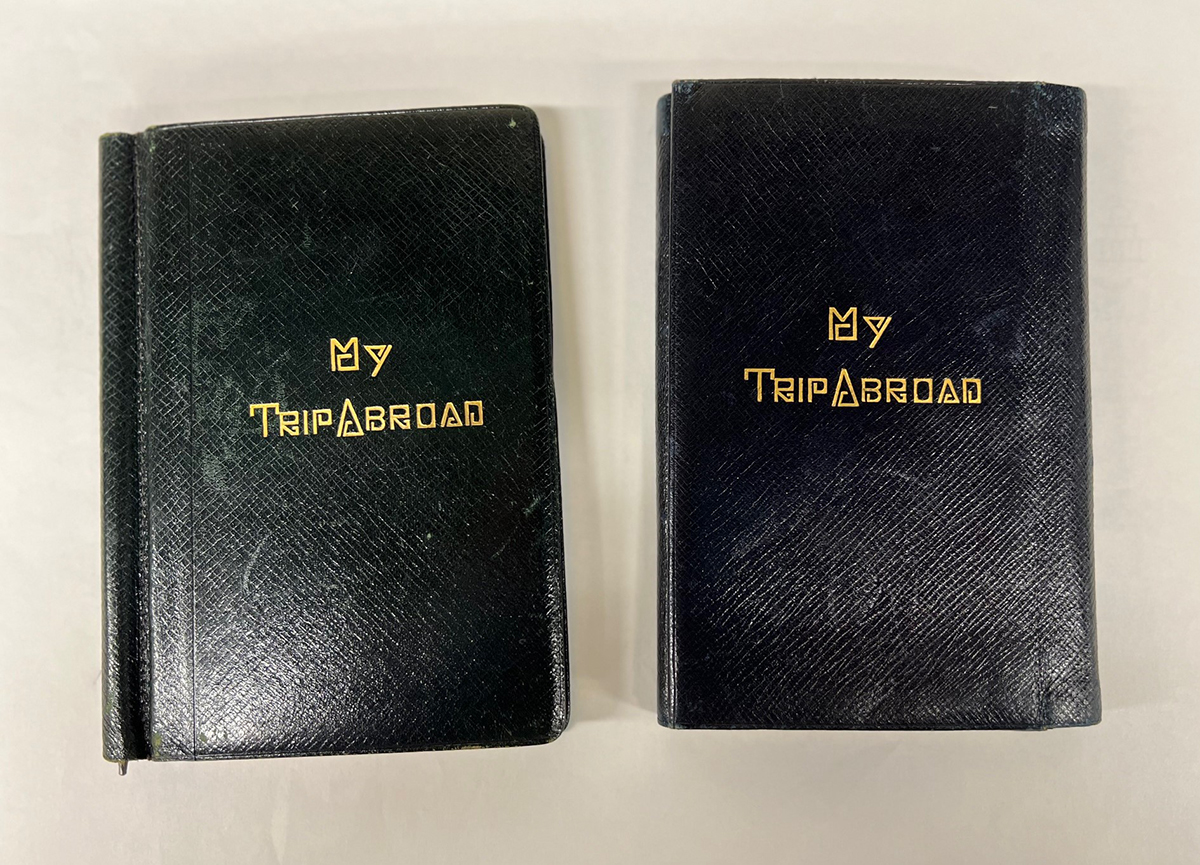

Clara Ford Travel Diaries. Accession 1, Box 105 and 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

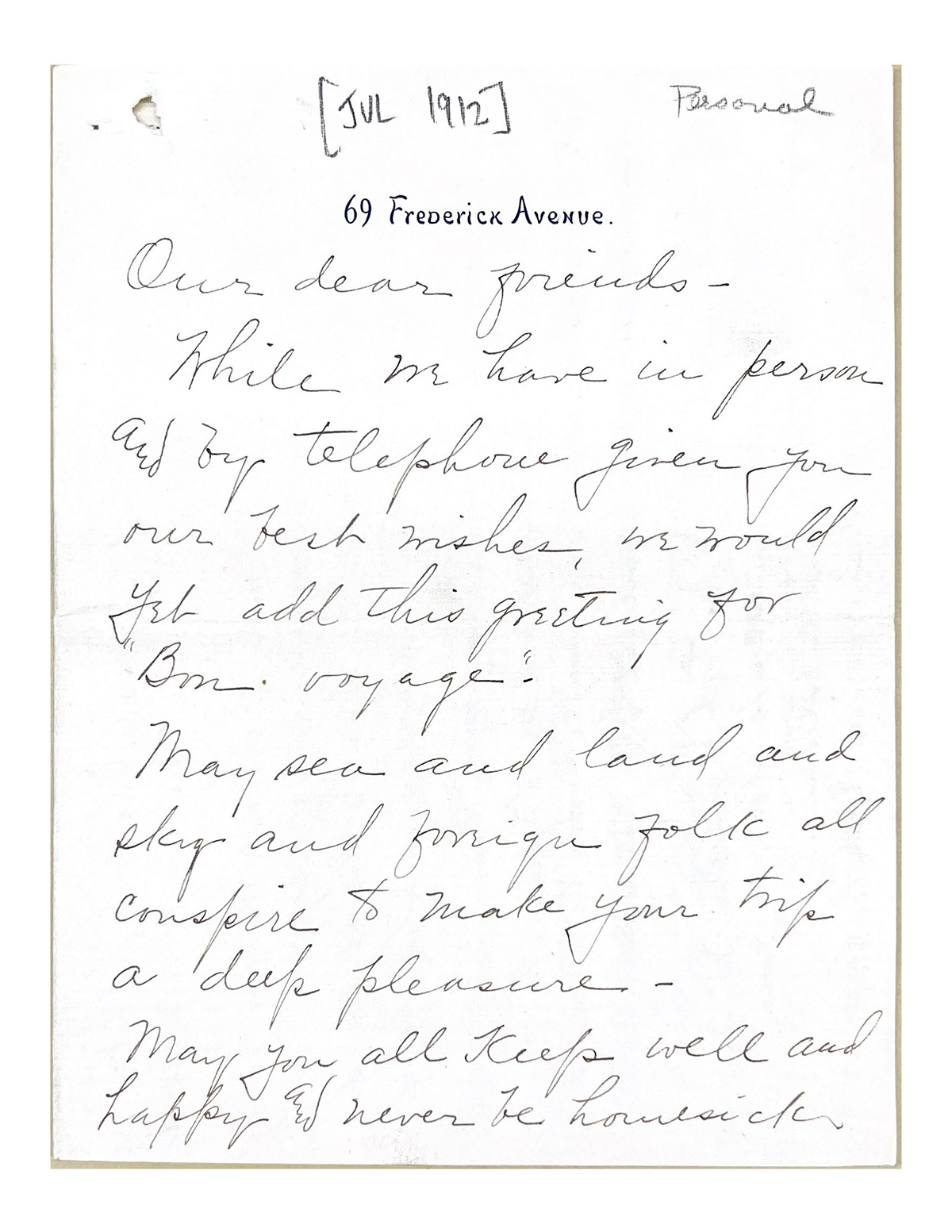

Unlike social media posts, travel diaries were not always intended for sharing or future publication. Entries were meant to document travel details and for personal reflection.

This means the writer was often sharing their thoughts more freely. For a notable figure like Clara Ford, travel diaries provide insight into her personal opinions and interests that might have been left out of an official record of her travels. They also provide a valuable record of Clara at a given time and place. They tell us who she interacted with, where she stayed, and what she saw.

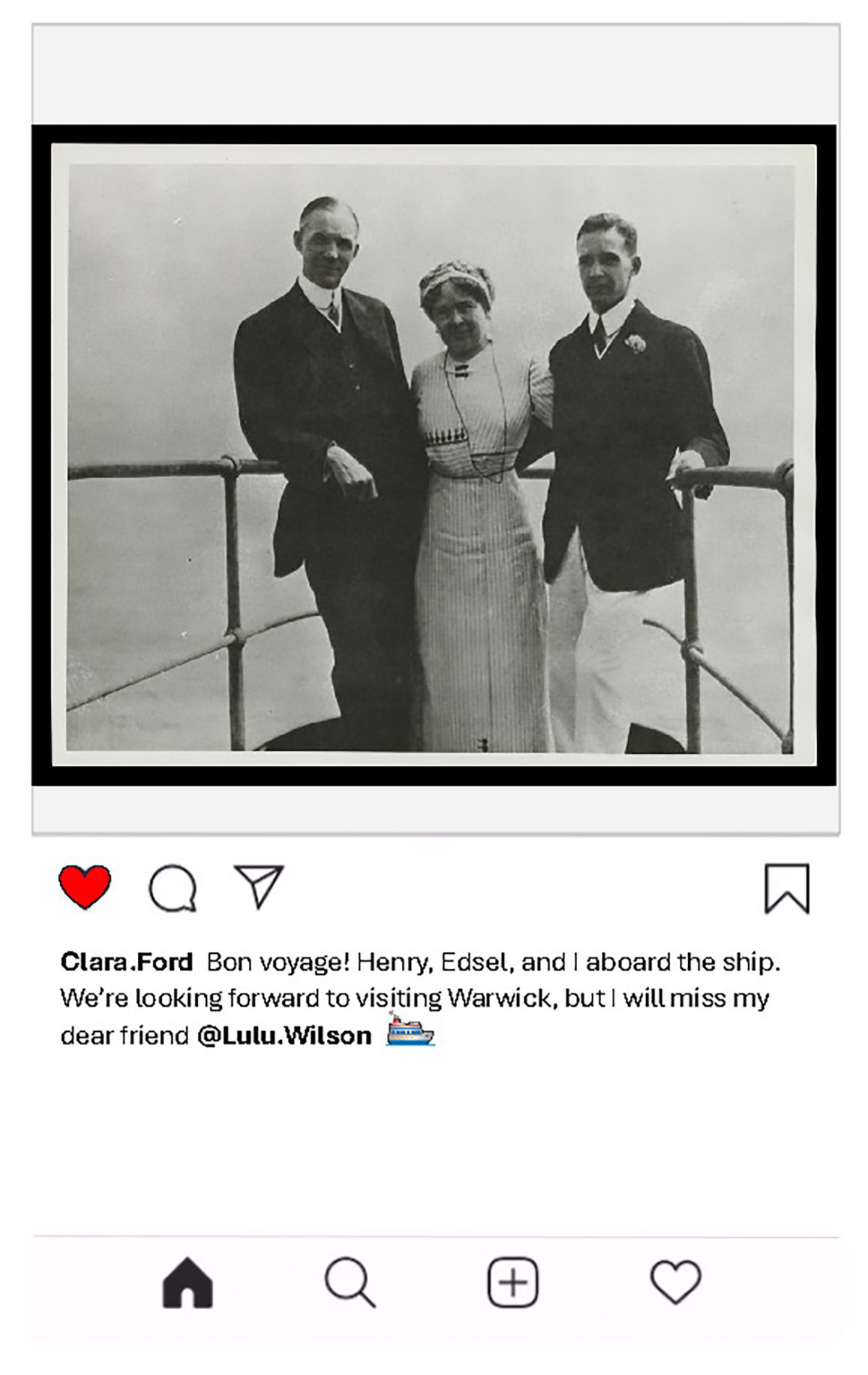

The earliest travel diary penned by Clara was for her first trip to Europe in 1912. She, Henry, and Edsel explored sites throughout Great Britain and France.

Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford aboard Ship on their European Trip, 1912. / THF117563

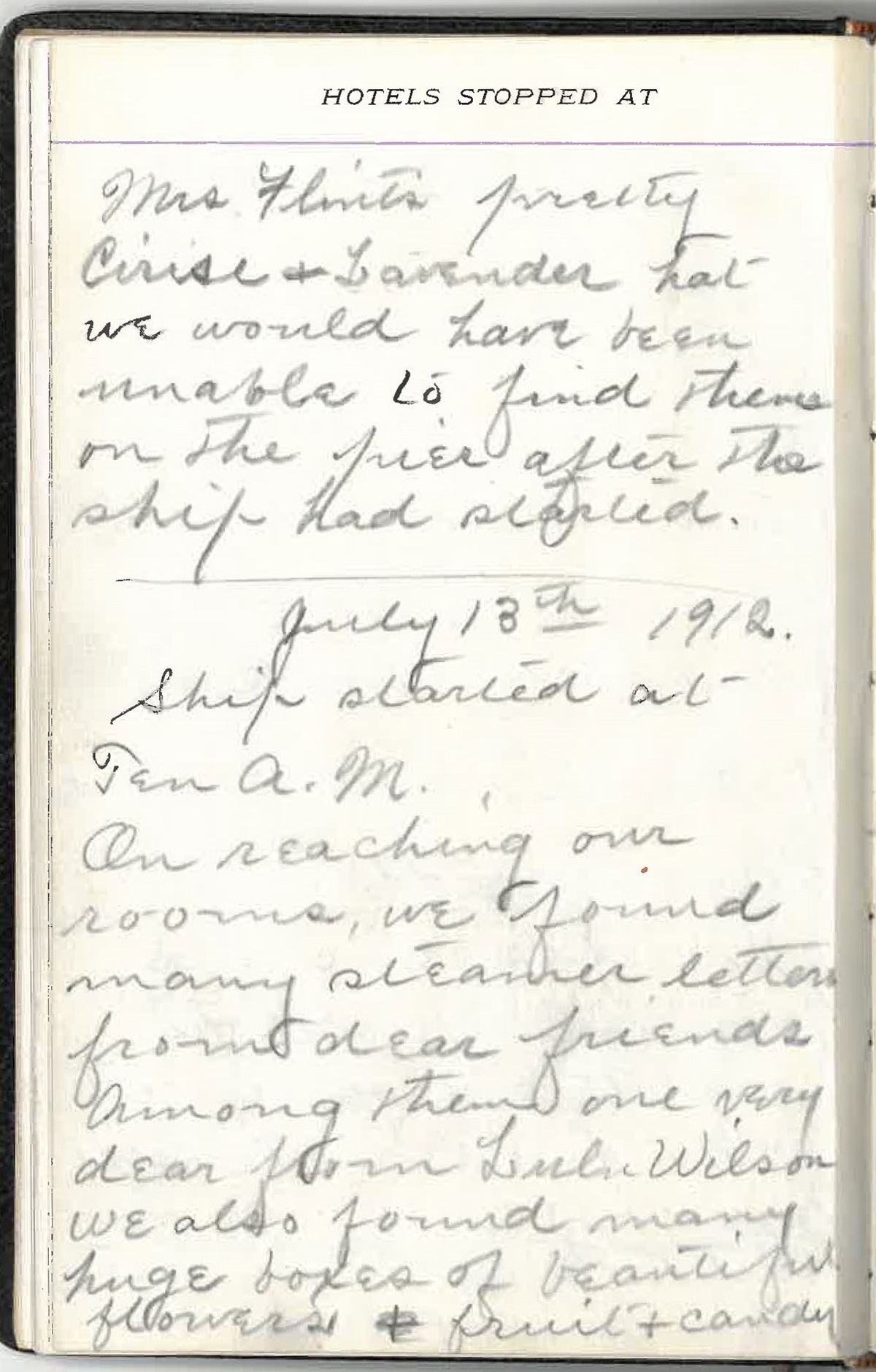

In one of the first entries, Clara documents the time the ship set sail and describes the warm welcome they received. Among flowers, fruits, and candy were several letters from friends wishing them a “Bon Voyage!” Clara references a letter from her close friend, Lulu Wilson, which we also hold in our collection. Connecting archival records like these illustrates a larger picture for historians and researchers.

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Letter to Clara Ford from her friend Lulu Wilson, July 1912. Accession 1, Box 66. / Image by Lauren Brady

In addition to Clara's diary, we also have Edsel's diary from this trip in our collection.

Clara Ford's and Edsel Ford's Travel Diaries, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

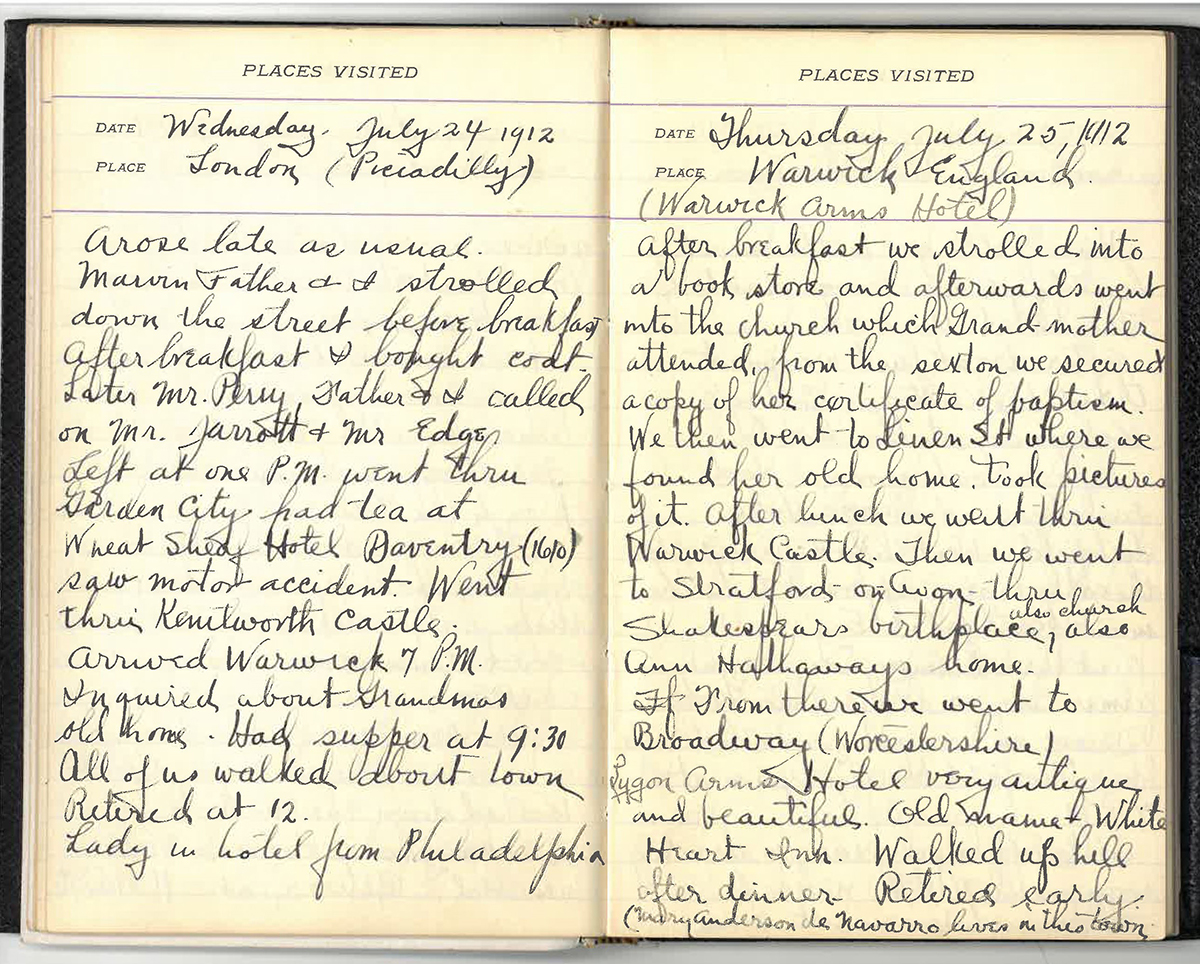

During their travels, they visited Clara's ancestral home. There are parallel accounts of the visit in both diaries. It reads as a meaningful visit for Clara who also describes important genealogical details about her family history that may not have been recorded elsewhere in our archival collections.

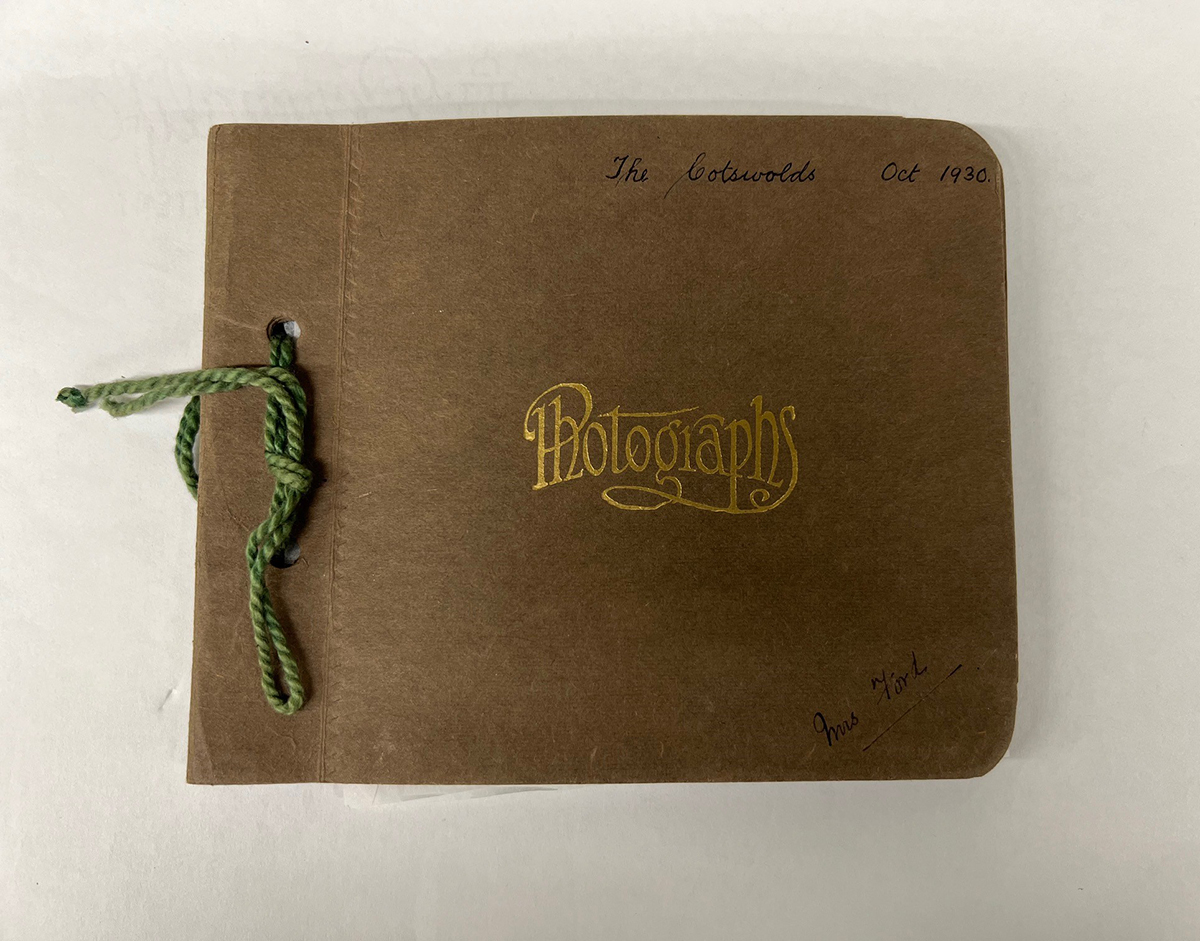

Edsel Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

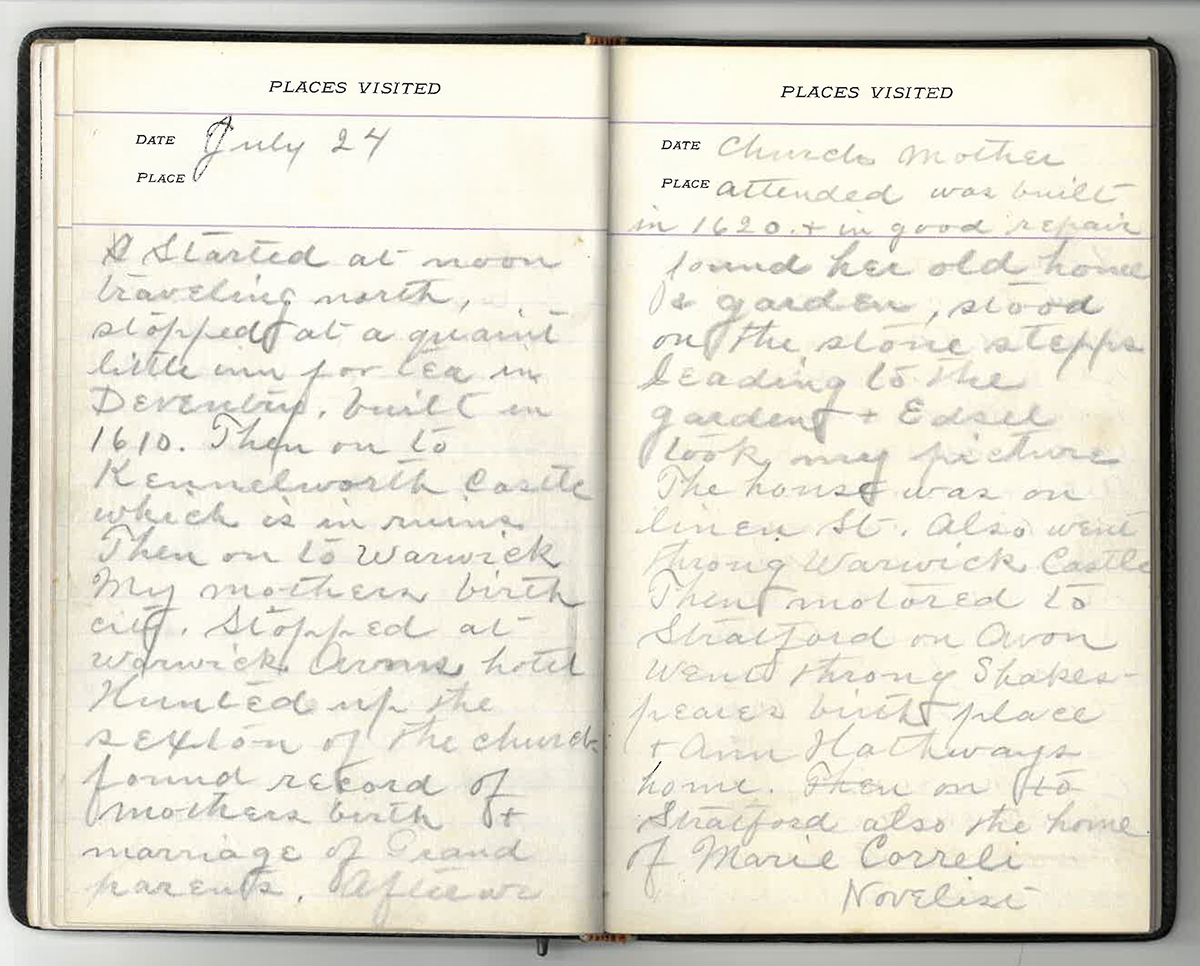

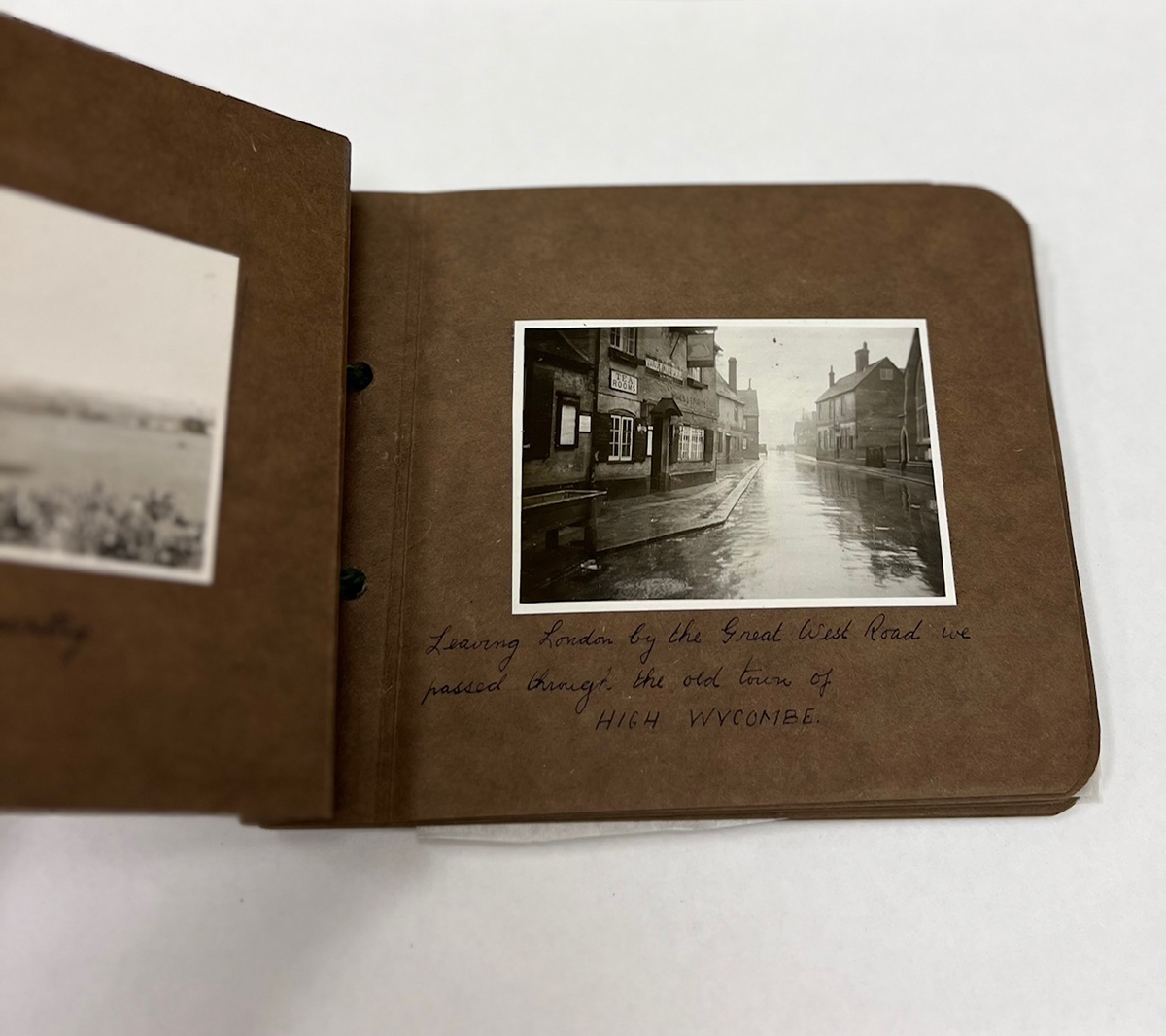

The Fords returned to Europe many times, including a trip in 1930 which Clara documented in a diary and a unique photo album. In her diary, Clara makes note of Henry's visit to Buckingham Palace before he departed for the Cotswold region of England where Cotswold Cottage had recently been acquired for Greenfield Village.

This visit received special commemoration in a photo diary with handwritten notes by Clara.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

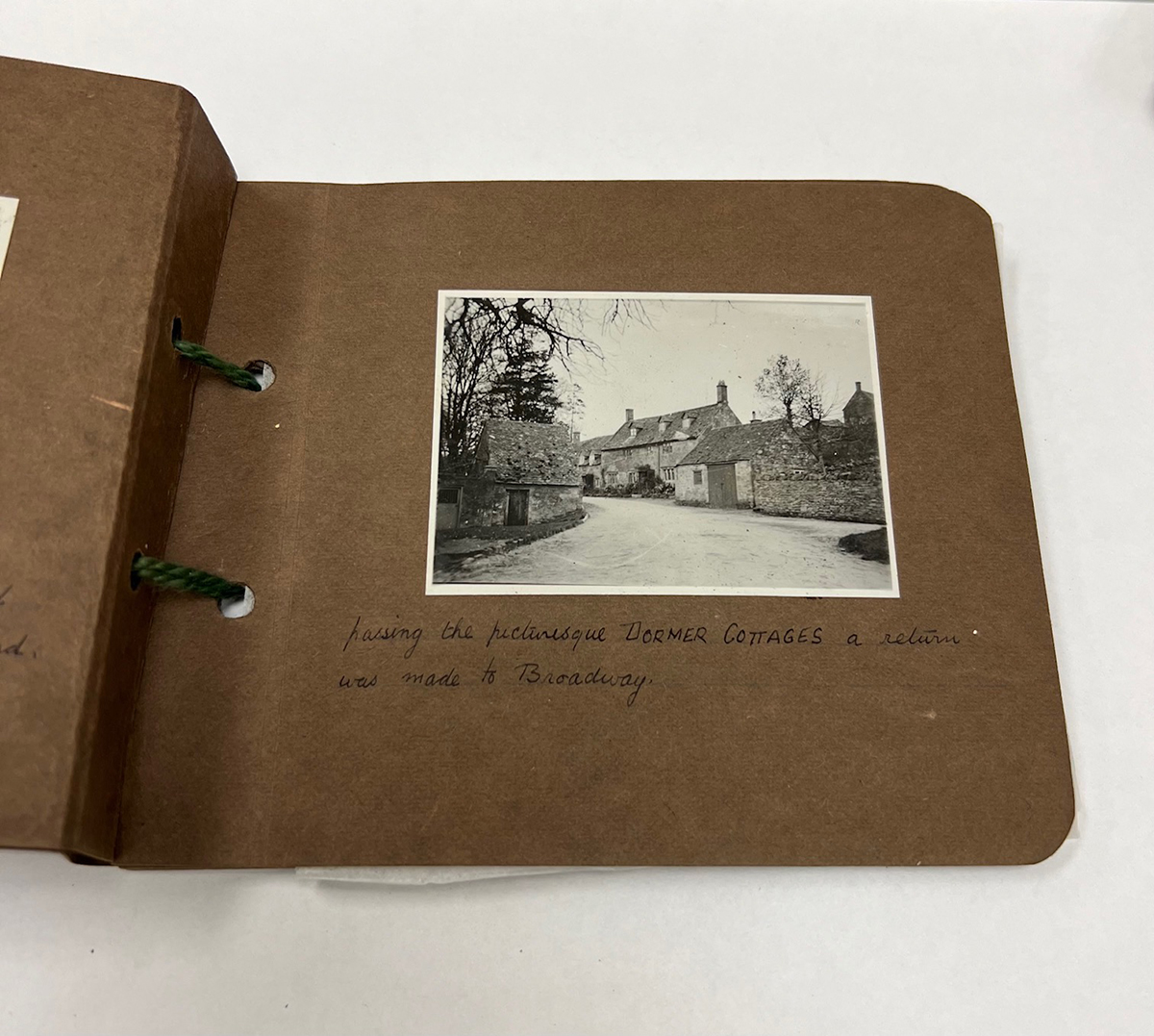

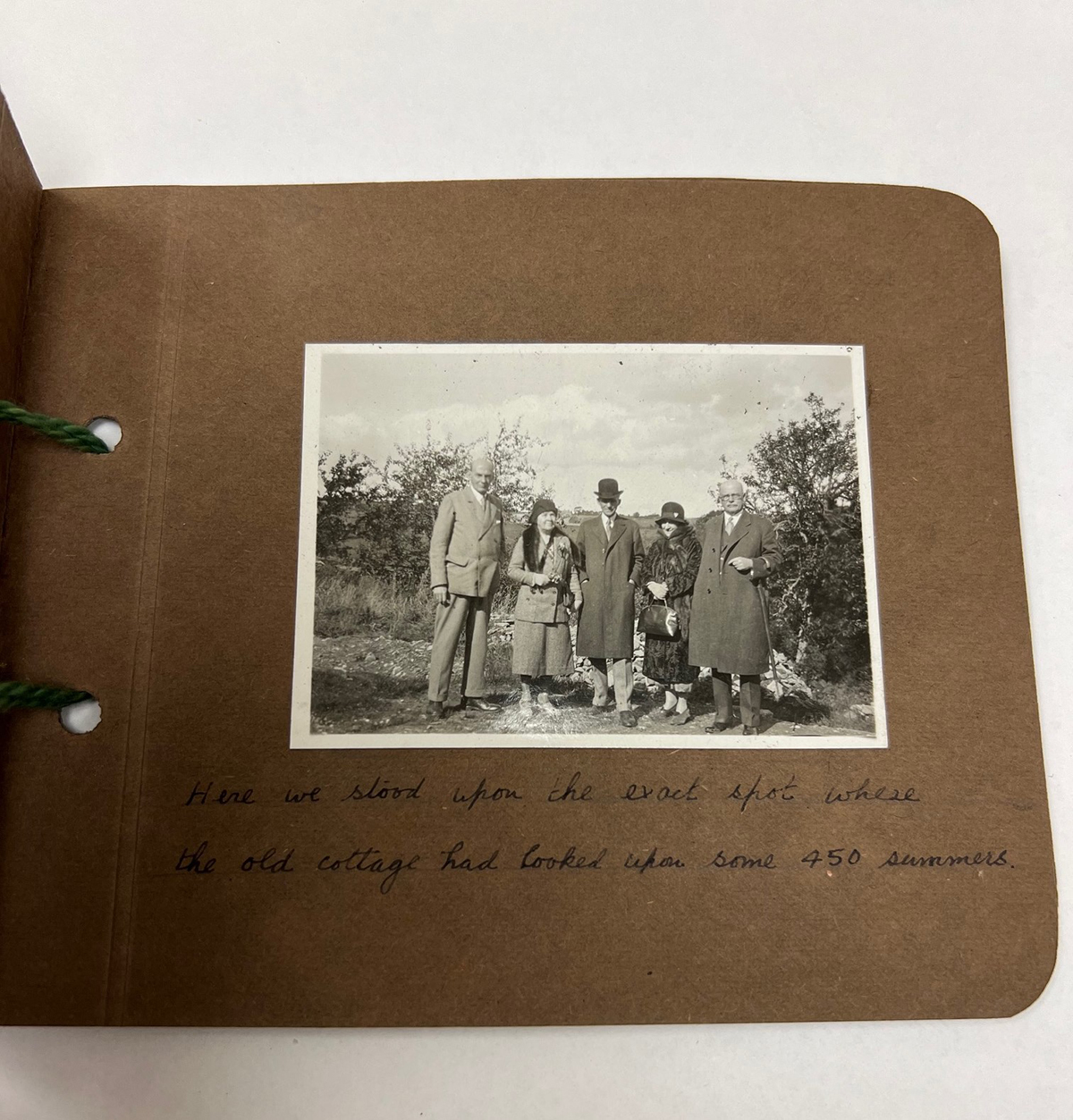

The album includes several snapshots of their visit culminating with a group photo at the former site of Cotswold Cottage. Clara's notes read like a short story as she describes the photos and recounts details.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara's diary entries with descriptions of cities and historic sites she encountered are valuable to historians looking for written records of landscapes altered by wars and other major events. Her words help us understand Clara Ford as a historical figure, but they also help us understand a location as it stood at that moment in time.

We are grateful to have these valuable archival records, but it is fun to wonder how a modern Clara may have documented her travels. Perhaps a post like this...

If you have any questions or would like to learn more about our collections, please contact the Benson Ford Research Center at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Lauren Brady is a reference archivist at The Henry Ford.

Edsel Ford, Ford family, Henry Ford, Clara Ford, by Lauren Brady

Mopar Muscle at Motor Muster 2024

This 1970 Plymouth Road Runner Superbird, designed for NASCAR competition, exemplified this year's Mopar Muscle theme. / Image by Matt Anderson

Another summer is here, bringing with it another edition of our popular Motor Muster in Greenfield Village. Part car show, part street fair, and all fun, this year's event brought together more than 600 cars, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, campers and boats all dating from 1933 to 1978. We like to spotlight a particular theme at each Motor Muster. This year marks the centennial of the first automobiles built and sold under the Chrysler Brand. Obviously, the 1924 model year is too early for our Motor Muster timespan, so we opted to celebrate Mopar Muscle — the Barracudas, Challengers, Chargers, Road Runners and more that made the Chrysler family of makes so popular during the muscle car era. Chrysler introduced the Mopar Brand in the 1930s for its original-equipment parts. ("Mopar" is a portmanteau of "motor" and "parts") But by the heyday of the muscle car in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mopar was synonymous with high-performance cars from Chrysler's nameplates — especially Dodge and Plymouth.

Detroit Central Market was filled with representative Dodge and Plymouth muscle cars, in keeping with 2024's Mopar Muscle theme. / Image by Matt Anderson

Motor Muster routinely brings a stellar turnout of Chrysler-family muscle cars, and 2024 was no exception. This year we featured some of the best in Detroit Central Market. We always like to put interesting pieces from The Henry Ford's own collection in the Market, too. As extensive as that collection is, we don't have any muscle cars from the Chrysler brands. (We do have a 1965 example of the Pontiac GTO — widely considered the first true muscle car.) Instead, we featured three unusual Chrysler products. Our 1937 Chrysler Airflow represented the company's bold step into streamlining in the 1930s. Company founder Walter P. Chrysler had high hopes for the curvy car, shaped in part through wind tunnel tests. The Airflow's interior and mechanical components were equally significant, engineered to provide maximum comfort for passengers. Introduced for 1934 and sold under the Chrysler and DeSoto names, the Airflow attracted unprecedented attention from reporters and customers alike. But the car's many innovations caused production difficulties. Its unconventional looks — particularly its front end — also gave would-be buyers pause. Chrysler toned down the styling in subsequent model years, but Airflow sales still failed to meet expectations. DeSoto's version was cancelled in 1936, and Chrysler's ended after the 1937 model year.

This 1940 Chrysler Crown Imperial Parade Car carried VIPs through New York City for almost 20 years. / Image by Matt Anderson

Our 1940 Chrysler Crown Imperial Parade Car had a happier story. The stately car went to New York City where it served as the Big Apple's official parade car for nearly two decades. More than a hundred dignitaries — politicians, military leaders, diplomats, and notable personalities in the arts, sciences and athletics — rode in the car in ticker-tape parades through Manhattan's famed “Canyon of Heroes.” Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ralph Bunche, Winston Churchill and A. Philip Randolph were just some of the parade car's many distinguished passengers.

Our Chrysler Turbine engine from 1964 was no less important in terms of its technology. Turbine engines use the power of compressed, heated air to turn turbine blades that provide rotary motion to a car's wheels. Mechanically, turbine engines are far simpler than conventional piston engines, and this fourth-generation Chrysler turbine unit boasted 80 percent fewer moving parts. Turbines are also enormously flexible in terms of fuel. This engine could run on anything from unleaded gas to diesel fuel to kerosene to peanut oil. Many companies experimented with gas turbine engines after World War II, but only Chrysler put them into the public's hands. Chrysler built 50 turbine-powered cars and lent them to everyday Americans to get real-world feedback. Users loved the smooth ride and low maintenance but complained about sluggish acceleration and poor fuel economy. Most of the 50 cars were scrapped, but Chrysler gifted a complete car and the showcased engine to The Henry Ford in 1966. Chrysler ended its turbine development program in 1979.

It's not a car, but this late 1970s boat is indeed a Chrysler product. / Image by Matt Anderson

In recent years, Motor Muster has grown to include a small number of boats and outboard boat motors, displayed in their element alongside Suwanee Lagoon. Although it's an often-overlooked part of the company's history, Chrysler manufactured boats and boat engines for some 15 years, from the mid-1960s into the early 1980s. Chrysler Marine (the company’s watercraft division) built everything from small fishing boats to speedboats to sailboats. Some of its marine products shared parts — and even model names — with the company's automobiles. This year's Suwanee Lagoon exhibit included a Chrysler Marine boat built and used in the late 1970s for the company's own testing and development program, as well as a number of Chrysler outboard motors.

The two-seat yellow and white vehicle seen here was branded a PPV — a people-powered vehicle / Image by Matt Anderson

While the cars are the stars, Motor Muster always features several trucks, fire engines, motorhomes, travel trailers, motorcycles and bicycles, all from the mid-1930s to the late 1970s. Highlights from the pedaled class included a 1973 PPV, or People-Powered Vehicle. These two-seat conveyances were built by the EVI company of Sterling Heights, Michigan, and sold for about $380. They had room for two people (each of whom could help pedal) and space for luggage. Though the PPV had some appeal during those oil-crisis days of soaring gasoline prices, it wasn't practical enough to completely replace the family car.

This 18-foot Holiday House travel trailer offered an alternative for those not fond of Airstream's bulbous look. / Image by Matt Anderson

As is custom, auto camping historian Daniel Hershberger assembled and presented on a wonderful collection of mid-20th century travel trailers and cars near Scotch Settlement School. Highlights included a 1962 Holiday House trailer. Improbably, these trailers were the brainchild of David Holmes, president of the Harry & David mail-order fruit basket company. Fruit baskets were a highly seasonal business, peaking in the fall and through the December holidays. Holmes, looking to keep his employees and facilities busy during the rest of the year, hit on the idea of building travel trailers, which sold best in spring and summer. Holiday House offered trailers in 17-, 19- and 24-foot lengths, with gleaming aluminum skin over wooden frames. Unfortunately, the idea didn't work as well as Holmes had hoped, and Holiday House trailers were only produced for a few years. Recently, the brand name was revived on modern trailers built by another manufacturer.

In addition to Mr. Hershberger's presentations, two other experts offered talks throughout the weekend in Martha-Mary Chapel. Jim Johnson, Director of Greenfield Village and Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes, spoke about the unique challenges of driving during World War II, when new cars weren't being manufactured and rubber and gas rationing curbed Americans' non-essential travel. We also had a special guest presenter. Richard J.S. Gutman shared stories and photos from his lifetime studying, visiting and preserving America's roadside diners. Mr. Gutman's timing couldn't have been better — he and his work are the subjects of the current Dick Gutman, DINERMAN exhibit in the Collections Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Historians Roger Wojtkowicz, Jim Wagner and John Wagner provide commentary on a 1956 Chevrolet during pass-in-review. / Image by Matt Anderson

Beyond the special presentations, Motor Muster 2024 saw the return of our popular pass-in-review sessions, in which expert historians offer insights on participating vehicles as they drive past the Main Street reviewing stand. Automobiles were broken into separate sessions by decade, while commercial vehicles, motorcycles, bicycles and race cars each had their own dedicated pass-in-review programs. Naturally, we held special Mopar Muscle sessions on both Saturday and Sunday to celebrate this year's theme.

Competition cars like the 1941 Allard K1 at left and the 1962 Austin Mini Cooper at right – British vehicles both – sat near Town Hall. / Image by Matt Anderson

If all those motor vehicles and programs weren't enough, Motor Muster also featured a range of historic vignettes keyed to each of the show's five decades. Timeless Blues music was heard from the porch of the Mattox Family Home, the Village Cruisers vocal group performed a medley of 1950s hits at the Lodge, and the Together Band provided a concert of 1970s classic rock on the Main Street stage on Saturday evening. And yes, there was Historic Base Ball, too, as Greenfield Village's own Lah-De-Dahs played three games over the weekend.

The whole event was capped on Sunday afternoon with our awards ceremony. Visitors got to choose their favorite vehicles from the various decades through popular choice voting. We also gave two Curator's Choice prizes for unrestored vehicles. This year's unrestored winners included a 1951 Ford Deluxe and a 1973 Oldsmobile Cutlass S. The full list of winners is available here. The ceremony provided a perfect end to another great show.

Matt Anderson is curator of transportation at The Henry Ford.

When Freedom Came: Remembering the Origins of Juneteenth

As we come into the season for exploring and celebrating Americanism, it's important to remember that the promises of freedom have ebbed and flowed to different groups in different ways. No other group in the United States has a more delicate relationship with freedom than African Americans. In 2021, Juneteenth was recognized as a federal holiday — an event with long-standing roots in Texas Black history with important connections for modern celebrations.

When did slavery in the United States come to an end? Generally, most people believe that the January 1, 1863 Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln freed all enslaved Africans and African Americans in the country at one time. In reality, freedom came slowly over time for most people. The Emancipation Proclamation, a wartime measure, explicitly freed men, women and children in Confederate-occupied territories — places that were taken over by the Union earlier in the war, like New Orleans, Louisiana, were not considered free places. Of course, enforcement of the condition of slavery was lacking in these spaces, and thousands of self-emancipating people flocked to Union camps and occupied cities, knowing that their chance at freedom was better with President Lincoln's Army.

Despite the declaration of emancipation in the Confederacy, freedom was dependent on the word getting out from Union soldiers directly. In a world before cellphones, email and the internet, a vulnerable population like enslaved people, who were not allowed to read and write in most places, would be dependent on their enslavers to share news of events. Groups on the far edges of the confederacy who still needed to exploit the labor of their enslaved workforce often kept people in bondage well beyond Lincoln's announcement. In these cases, it wasn't until Union troops arrived in the area that the end of slavery was not only acknowledged but made a physical fact within these communities.

Juneteenth recognizes June 19, 1865, when Army Major. General Gordon Granger marched his troops into Galveston, Texas, and read out loud for all to hear that freedom for all was now the law — over two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was announced, two months after the end of the Civil War and four months after the ratification of the 13th Amendment.

Joint Resolution of the United States Congress, Proposing the 13th Amendment to Abolish Slavery, 1865 / THF118475

The first Juneteenth in Galveston was celebrated June 19, 1866 with particular traditions that have survived today. These few key elements included: food items that are red in color, reflections on the resilience of enslaved people, a celebration of freedom, and uplifting of Black economic and community power. Red symbolizes the blood of Africans and their descendants in America, shed through the international and domestic slavery trade. This color is reflected in foods eaten at these celebrations, like red velvet cake, smoked barbecue, watermelon and some kind of red drink that could be something floral like hibiscus, a native African flower used to make an iced tea, or something more sugary sweet.

Author and chef Nicole A. Taylor published Watermelon & Red Birds: A Cookbook for Juneteenth and Black Celebrations in 2022, the first of many cookbooks to explore Juneteenth published by major presses. Taylor explores the essential food history of Juneteenth and gives us some new spins on these wonderful delicacies.

Watermelon & Red Birds: A Cookbook for Juneteenth and Black Celebrations

Today, Juneteenth celebrations occur all over the country, providing an excellent opportunity to explore the uniqueness of Black American culture, taste amazing delicacies and reflect on our collective future with an eye toward freedom and liberty for all.

Amber N. Mitchell is curator of Black history at The Henry Ford.

Join us in celebrating Juneteenth with an emancipation picnic at the Mattox Family home in Greenfield Village.

Photo courtesy of the Greenfield Village Living History team

Juneteenth is the nationally recognized holiday celebrating the end of American chattel slavery and commemorating the day enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, were finally freed on June 19, 1865. On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, announcing his intention to free enslaved people held in Confederate states. When the proclamation went into effect on New Year’s Day 1863, his signature alone was not enough to free them all. The Union Army could only enforce the Emancipation Proclamation where it had taken control of Confederate territory, leaving the Confederate South emancipated in a patchwork of liberation across the states. Emancipation for the enslaved people of Galveston came nearly two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.

Continue ReadingRemembering Parnelli Jones (1933-2024)

Parnelli Jones signing autographs at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 1967. / THF144849

Auto racing lost a legend, and The Henry Ford lost a friend, when Parnelli Jones passed away on June 4, 2024. Rufus Parnell Jones (an aunt gave him his lifelong nickname, “Parnelli”) was born August 12, 1933, in Texarkana, Texas. His family moved to the Los Angeles area when he was young, and he grew up immersed in the racing and rodding culture of Southern California. Jones was building his own hot rods by age 17 and racing on local and regional tracks soon thereafter.

Early on, Jones distinguished himself with a brash, aggressive style behind the wheel. This, and a Midwest sprint car title Jones clinched in 1960, caught the attention of promoter J.C. Agajanian who gave Parnelli his ticket to the big time. Jones made his Indianapolis 500 debut in 1961, finishing in a respectable 12th place. The following year, he set a qualifying-speed record of 150.370 miles per hour. One year after that, in 1963, Jones won the race.

Parnelli Jones and his teammates at Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1963. J.C. Agajanian is in the suit and cowboy hat. / THF114555

Parnelli Jones’s Indy win was not without controversy. It came during a time of rapid change at the Indianapolis as 1963 brought the first appearance of the rear-engine Lotus-Ford cars and ace Scottish driver Jim Clark. For much of the race, Jones, who’d won the pole position with the fastest qualifying time, battled with Clark and Dan Gurney, who also piloted a rear-engine Lotus-Ford. Clark and Gurney were quicker through the turns with their lithe Formula One-inspired cars, but Jones’s traditional front-engine roadster had the advantage on the straights with its higher top speed. Gurney’s car eventually succumbed to tire troubles, but Jones and Clark kept charging.

It was somewhere around lap 80 when officials first saw smoke intermittently wafting from Jones’s Offenhauser-powered Watson. The problem — a crack in the oil tank at the car’s rear — grew worse as the race continued. One hundred laps later, Jones’s car wasn’t just smoking, but purportedly leaving oil on the track. Per Indy’s rules, an oil leak called for Jones’s car to be black flagged — forced to the pits and effectively disqualified. J.C. Agajanian, owner of Jones’s car, pleaded his case to officials, claiming that the leak was easing as the oil fell below the level of the crack. Colin Chapman, campaigning Jim Clark’s car, argued for Jones to get the black flag.

After spirited debate, officials chose not to disqualify Jones. Instead of a black flag, Parnelli Jones took the checkered, with Jim Clark finishing second. Race fans still argue over how much of a factor that oil leak was and whether the black flag should have been used. But hypotheticals don’t mean much in the record books. Parnelli Jones earned his 1963 victory after leading 167 of 200 laps and maintaining an average race speed of 143.137 miles per hour — impressive numbers worthy of a winner.

Parnelli Jones in his turbine-powered car, built by Andy Granatelli, at Indy in 1967. / THF96164

Jones very nearly won at Indy again in 1967, behind the wheel of an unusual turbine-powered four-wheel-drive car, but a failed transmission bearing took him out as he led the pack just four laps from victory. Jones did win the Indianapolis 500 again as an owner. He partnered with Vel Miletich to form Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing, and the team earned back-to-back victories with driver Al Unser in 1970 and 1971. VPJ Racing’s “Johnny Lighting” cars are still loved by fans for their striking blue-and-yellow lightning-stripe livery.

Parnelli Jones and Bobby Unser at Pikes Peak in 1964. Jones took first in the stock car division that year, while Unser topped the sports car division. / THF262097

Parnelli Jones’s triumphs went beyond Indianapolis. Like other greats of his era, he raced everywhere — from dirt tracks to Pikes Peak and from NASCAR ovals to Trans-Am circuits. By the 1970s, Jones had largely retired from open-wheel, open-cockpit racing, but he found further success in off-road Baja races. Jones partnered with co-driver Bill Stroppe to win Mexico’s Baja 1000 in 1971 and 1972, and the Baja 500 and the Mint 400 in 1973. Jones and Stroppe ran the races in a modified Ford Bronco sponsored by Olympia Beer — source of the Bronco’s memorable nickname, “Big Oly.” When he wasn’t racing, Jones kept busy selling automotive parts and tires through his retail businesses.

In 2008, Parnelli Jones was kind enough to sit for an interview with The Henry Ford for our “Visionaries on Innovation” series. We asked Jones how he hoped to be remembered — a standard question in many of these interviews. Naturally, he wanted to be thought of as a great driver, one who could win in almost any form of auto racing. (Jones needn’t have worried about that. It’s exactly how he’s being remembered now.) But it speaks to something deeper in his character that, first and foremost, he wanted to be remembered as a good, honest person. It’s an epitaph any of us would be proud to have, and one that certainly fits Parnelli Jones. The racing world will miss him.

Parnelli Jones in 2008. / THF56305

Matt Anderson is curator of transportation at The Henry Ford.

The history of LGBTQ+ activism in the United States is long. For the past century, the struggle for equality has taken many forms and faced many challenges, as the LGBTQ+ community have fought for their rights and their lives.

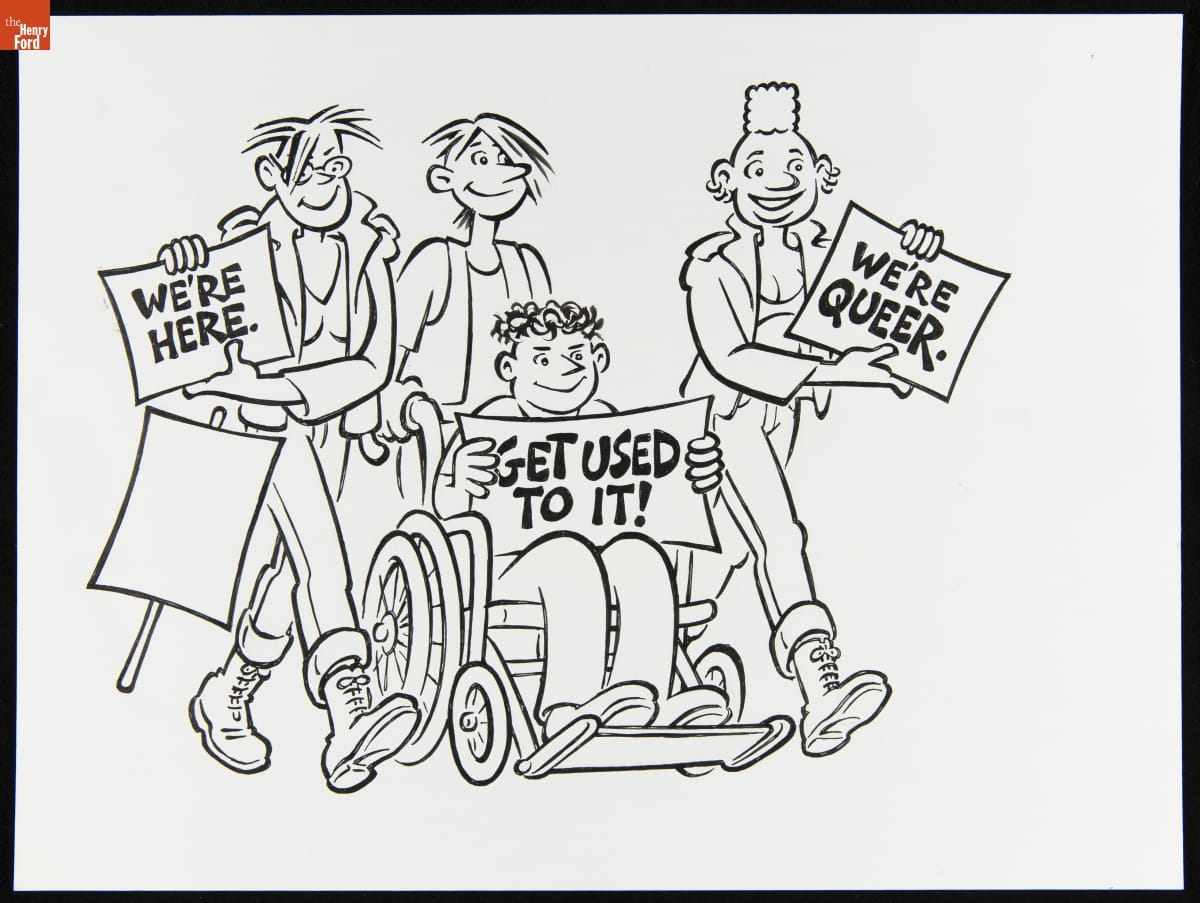

Illustration, "We're Here. We're Queer. Get Used to It!," circa 1995 / THF627364

Inspired by the developing gay community he encountered while working in Weimar Berlin, in 1924 German immigrant Henry Gerber legally incorporated the first homosexual organization in the United States — the Society for Human Rights. Black clergyman John Graves served as the organization’s first president. The society would exist for only a year before being forced to collapse due to lack of membership and legal prosecution, but during its short tenure, it published two editions of its “homophile” (an early activist term for “homosexual”) newsletter, Friendship and Freedom.

Continue ReadingWhat We Wore: Say Yes to the PROM Dress

The current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents a variety of prom dresses dating from 1960 to 2006 — and uncovers the stories they tell about this important rite of passage.

Proms are a much-anticipated milestone for many teenagers. High school students dress up in their most glamorous formal clothing to enjoy the much-anticipated event — an occasion guaranteed to create special memories.

For teen girls, especially, choosing the perfect dress is key to the experience! Weeks before the big event, what to wear becomes the hot topic of conversation at school and with friends. Traditionally, young women wear evening gowns — the hunt may involve a trip to local stores, searching online retailers, or even having a dress custom made. For young men, it’s simpler — they usually rent a tuxedo.

Continue ReadingDishing on Diners

The world’s expert on diners shares his start, describes his discoveries and explains his connection to The Henry Ford.

By Richard J.S. Gutman

My half-century immersion in the world of diners began with poached eggs on toast in the middle of the night at Bud’s Diner, hard by the railroad tracks, in Ithaca, New York. It was 1970, and I was on a break with classmates from an all-nighter at Cornell University’s School of Architecture. Seeking sustenance, I substituted a swiveling stool at the counter for an equally uncomfortable drafting stool up on the Arts Quad.

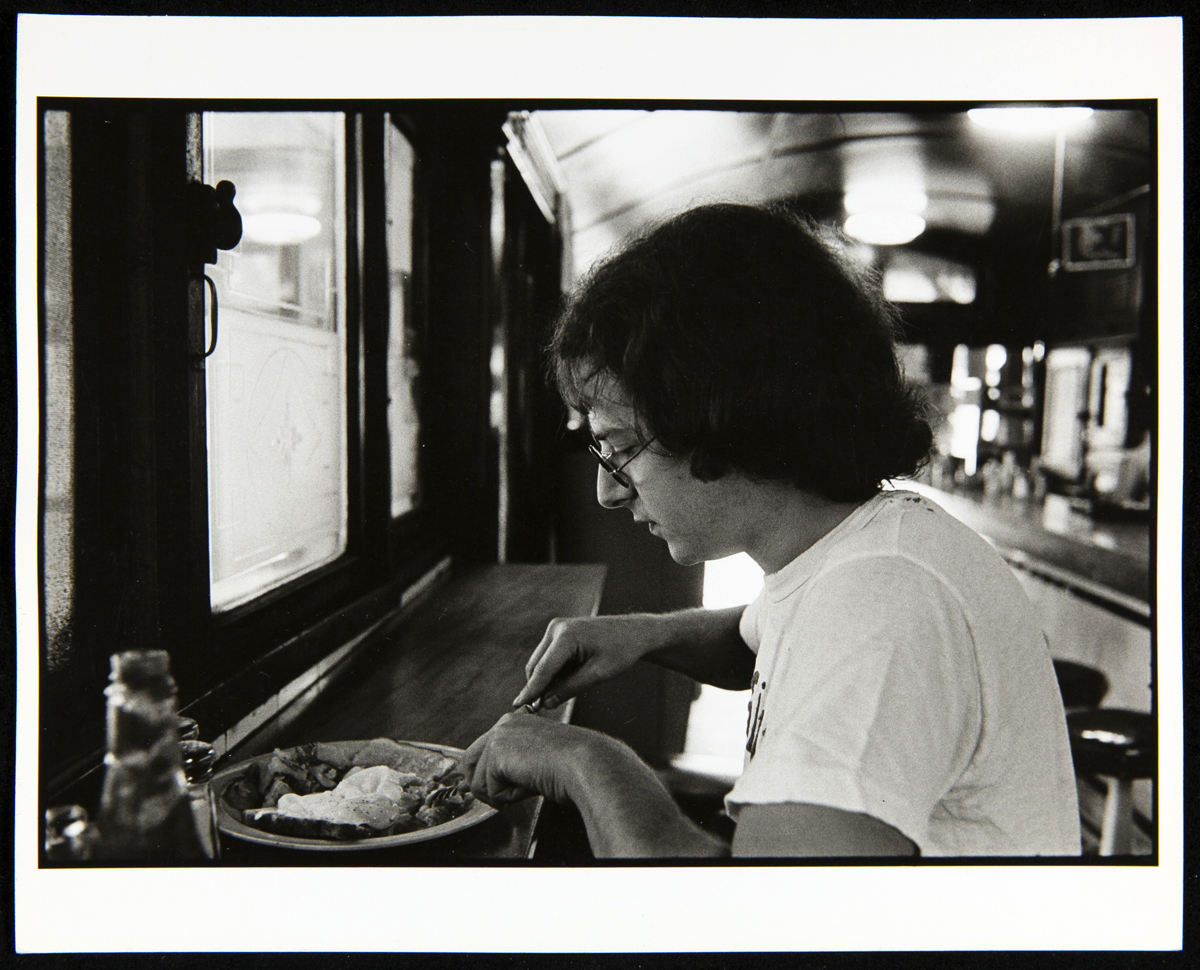

Photo by John Baeder

An authentic diner — a long, low structure built in a factory and hauled to a site equipped with cooking equipment, dishes and silverware — is a particular type of informal lunch counter restaurant, which in its heyday during the 20th century frequently appeared to be like an immobile railroad car, but a resemblance was the only connection to a train.

Continue ReadingHistory Outside the Box: Voices from the Past

History is often defined as a continuous, typically chronological record of important or public events or of a particular trend or institution. To this, Henry Ford would say “History is bunk.” Why would he say that? Because to him, history was more than stories or dates in books, famous pieces of artwork or even collections of the wealthy. History was much, much more. He felt, as many of us do today, that history is how people live and work every day and connect to the world around them, and that it can be kept in many different formats, from written to oral traditions.

With this mindset, Henry Ford sought a way to teach about everyday life. He did so by not only collecting the objects you can see in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation or Greenfield Village but by setting out to collect memories. This was done by instructing museum assistants H.M Cordell and J.A. Humberstone to create a questionnaire. In 1929, this questionnaire would be sent to people who were 75 years or older, Ford being 65 years of age himself at the time.

Continue Reading