Seventy-five Years of the George Washington Carver Cabin

| Written by | Jim Johnson |

|---|---|

| Published | 8/15/2017 |

Seventy-five Years of the George Washington Carver Cabin

| Written by | Jim Johnson |

|---|---|

| Published | 8/15/2017 |

This year, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of the George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village. There is not a great deal of specific information about this project in the archival collections, but here is what we do know.

Henry Ford’s connections and interest in the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute began as early as 1910 when he contributed to the school’s scholarship fund. At this time, George Washington Carver was the head of the Research and Experimental Station there.

Henry Ford always had interests in agricultural science, and as his empire grew, he became even more focused on using natural resources, especially plants, to maximize industrial production. He was especially interested in plant materials that could be grown locally. Carver has similar interest, but his focus was on improving the lives of southern farmers. His greatest fame was that of a “Food Scientist”, though he was also very well known for developing a variety of cotton that was better suited for the growing conditions in Alabama. Through the decades that followed, connections and correspondences were made, but it would not be until 1937 that the two would meet face to face.

Through the 1930s, work and research began to really ramp up in the Research or Soybean Laboratory in Greenfield Village. Various plants with the potential to produce industrial products were researched, but eventually, the soybean became the focus. Processes that extracted oils and fibers became very sophisticated, and some limited production of soy based car parts did take place in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as a result of the work done there.

In 1935, the Farm Chemurgic Council had its very first meeting in Dearborn. This group, formed to study and encourage better use of renewable resources, would meet annually becoming the National Farm Chemurgic Council. It was at the 1937 meeting, also held in Dearborn, that George Washington Carver, and his assistant, Austin Curtis, were asked to speak. Carver was put up in a suite of rooms at the Dearborn Inn, and it was here that he and Henry Ford were able to meet and discuss their ideas for the first time, face to face. During the visit, Ford entertained Carver at Greenfield Village and gave him the grand tour. Carver was also invited to address the students of the Edison Institute Schools. Carver would write to Ford following the visit, “two of the greatest things that have come into my life have come this year. The first was the meeting with you, and to see the great educational project that you are carrying on in a way that I have never seen demonstrated before.”

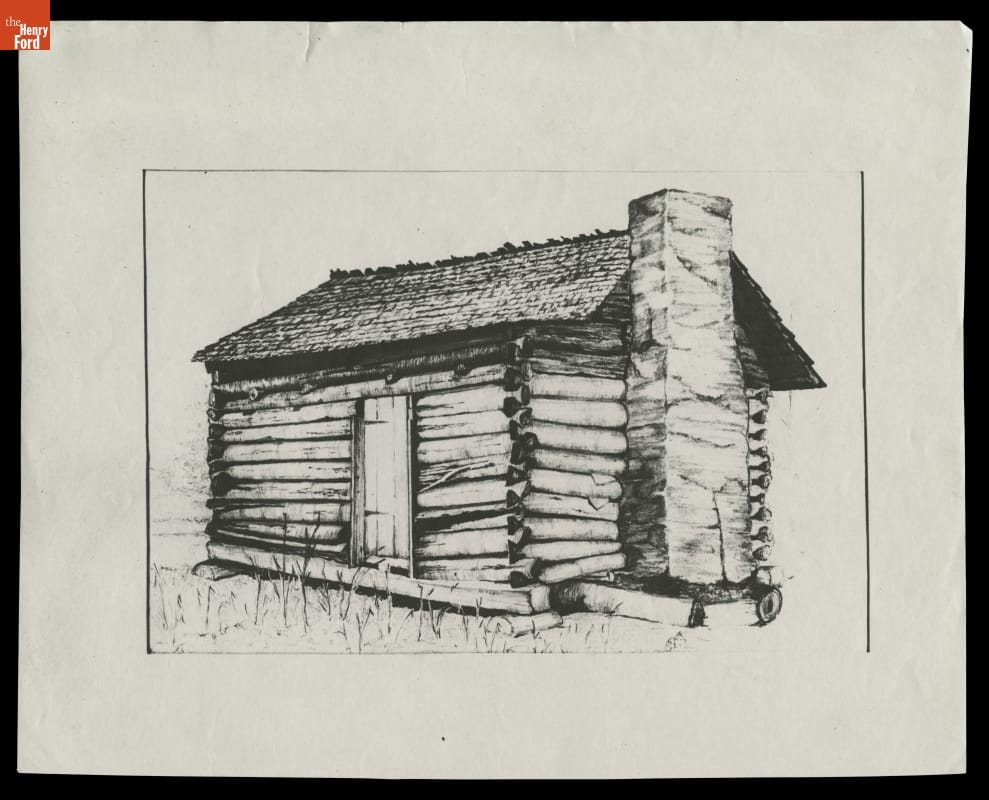

It was at some point during the visit that Henry Ford put forth the idea of including a building dedicated to George Washington Carver in Greenfield Village. It seems that he asked Carver about his recollections of his birthplace, and went as far as to ask for descriptions and drawings. Later correspondence from Austin Curtis in November of 1937 confirm Ford’s interest. It was determined by that point that the original building that stood on the farm of Moses Carver in Diamond Point, Missouri had long been demolished. Granting Ford’s request, Curtis would go on to supply suggested dimensions and a sketch, to help guide the project. The cabin was described as fourteen feet by eighteen feet with a nine- foot wall, reaching to fourteen feet at the peak of the roof. It included a chimney made of clay and sticks.

A 1937 rendering of the birthplace of George Washington Carver based on his recollections. No artist is attributed, but it is likely this was drawn by Carver. THF113849

It would not be until the spring of 1942 that the project would get underway. The building, very loosely based on the descriptions provided by Carver, would be constructed adjacent to the Logan County Courthouse. In 1935, the two brick slave quarters from the Hermitage Plantation, had been reconstructed on the other side of the courthouse. The grouping was completed with the addition of the Mattox House (thought to be a white overseers house from Georgia) in 1943. As Edward Cutler, Henry Ford’s architect, would state in a 1955 interview, “we had the slave huts, the Lincoln Courthouse, the George Washington Carver House. The emancipator was in between the slaves and the highly- educated man, It’s a little picture in itself.”

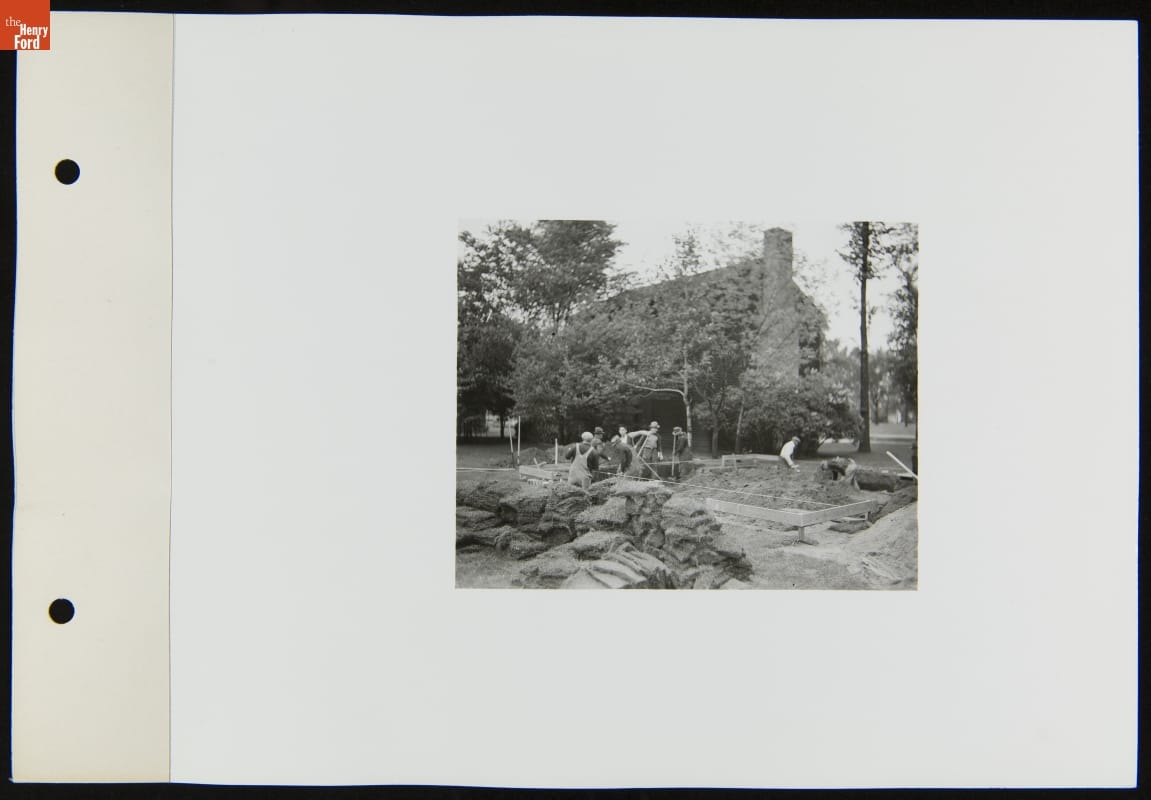

There are no records beyond Henry Ford’s requests for information as to how the final design of the building, that now stands in Greenfield Village, was determined. An invoice and correspondence does appear requesting white pine logs, of specific dimensions, from Ford’s Iron Mountain property. There is also an extensive photo documentation of the construction process in the spring and early summer of 1942.

Foundation being set, spring 1942. THF28591

Beginnings of the framing, Spring 1942. THF285293

Logs in place, roof framing in process, spring 1942. THF285285

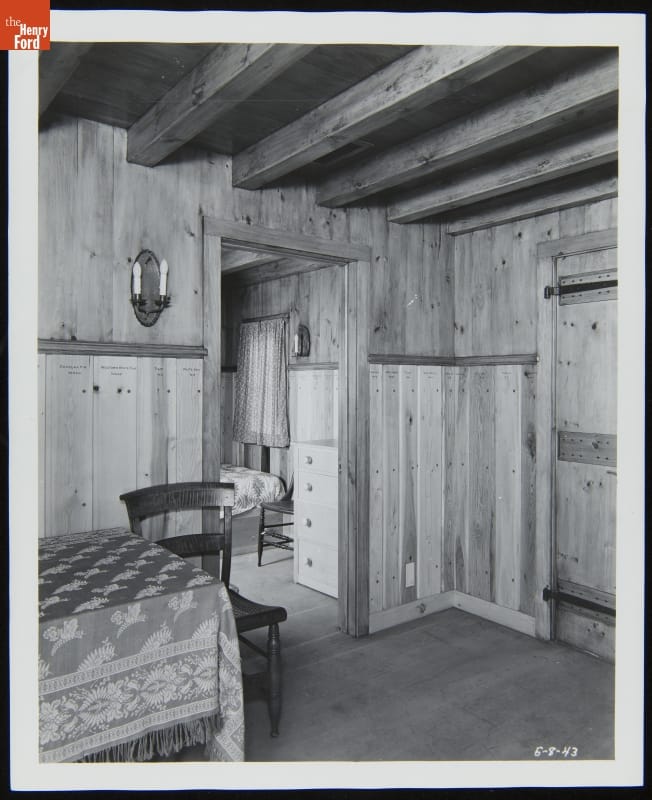

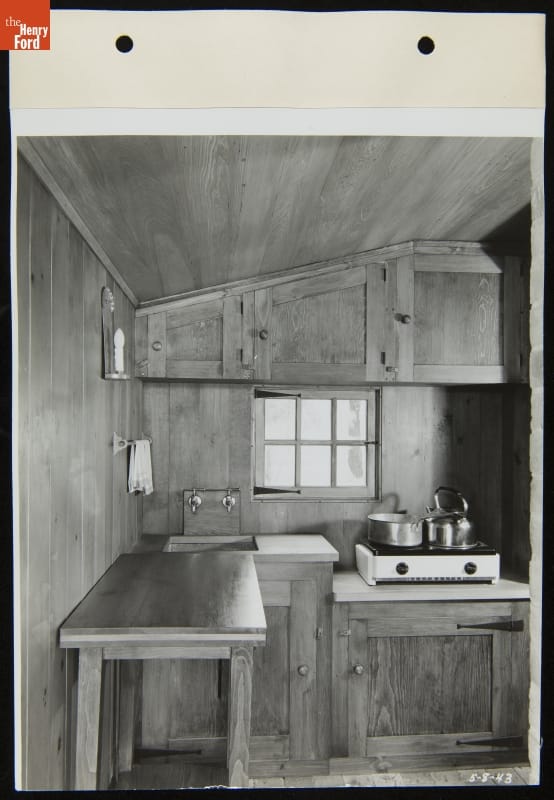

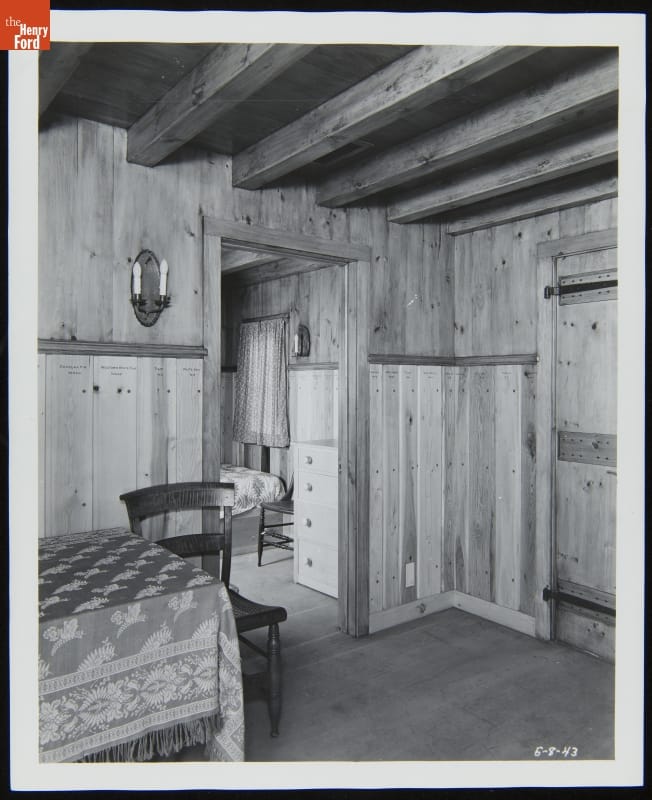

Newly Completed George Washington Carver Memorial, Early Summer, 1942. THF285295

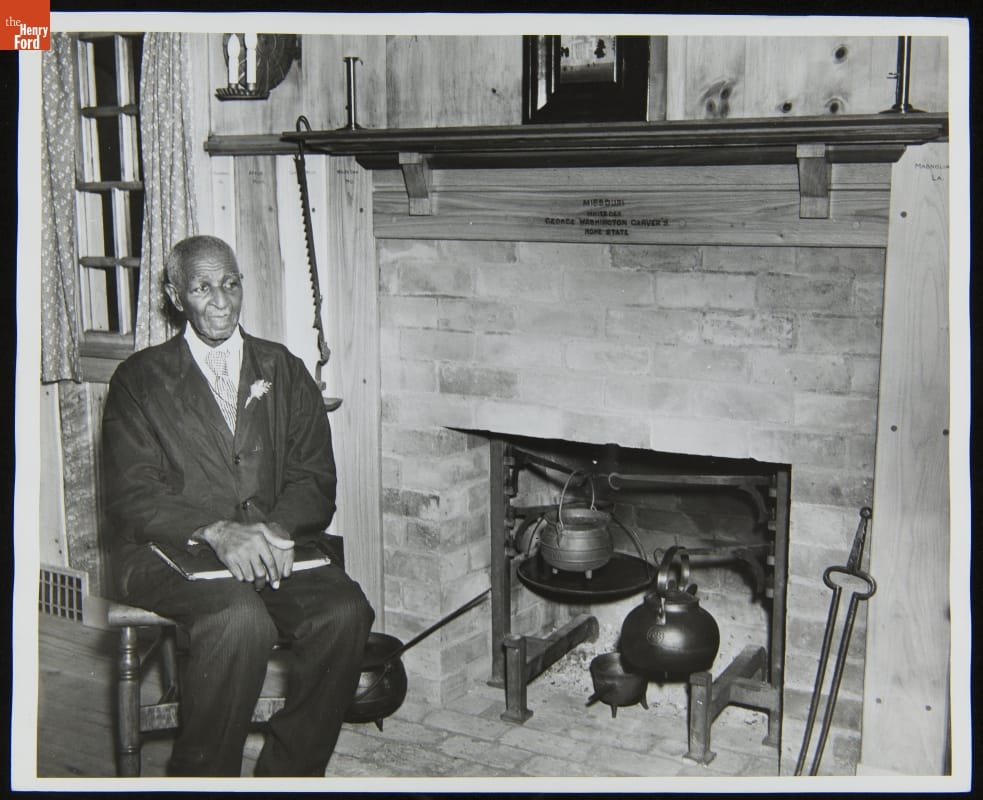

In the end, the cabin would resemble less of a hard scrabble slave hut, and more of a 1940s Adirondack style cabin that any of us would be proud to have on some property “up north”. It was fitted out with a sitting room, two small bedrooms (with built in bunks), a bathroom, and a tiny kitchen. It was furnished with pre-civil war antiques and was also equipped with a brick fireplace that included a complete set-up for fireplace cooking. As an interesting tribute to Carver, a project, sponsored by the Boy Scouts of America, provided wood representing trees from all 48 states and the District of Columbia to be used as paneling throughout the cabin. Today, one can still see the names of each wood and state inscribed into the panels.

Plans had initially been made for Carver to come for an extended stay in Dearborn in August of 1942, but those plans changed and he arrived on July 19. This was likely due to Carver’s frail health and bouts of illness. While the memorial was being built, extensive plans were also underway for the conversion of the old Waterworks building on Michigan Avenue, adjacent to Greenfield Village, into a research laboratory for Carver. The unplanned early arrival date forced a massive effort into place to finish the work before Carver arrival. Despite wartime restrictions, three hundred men were assigned to the job and it was finished in about a week’s time.

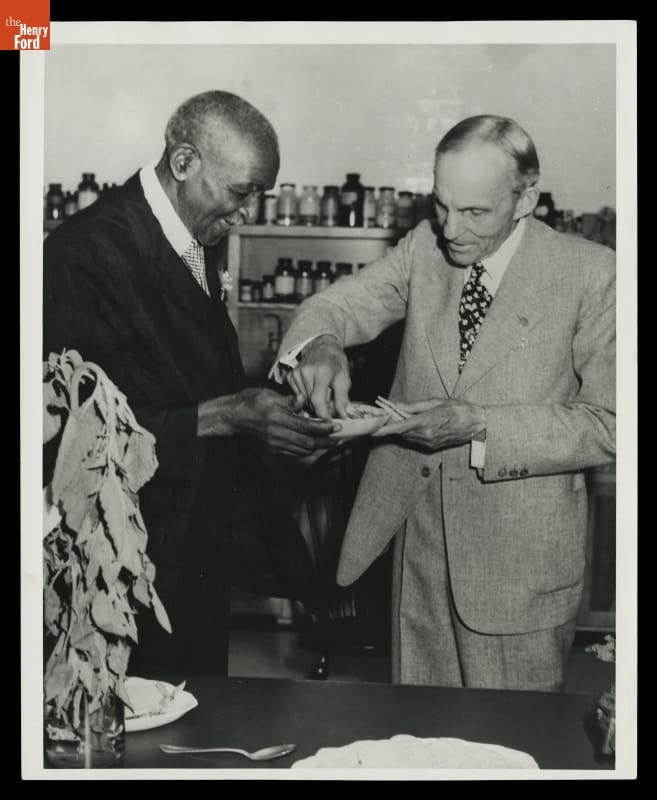

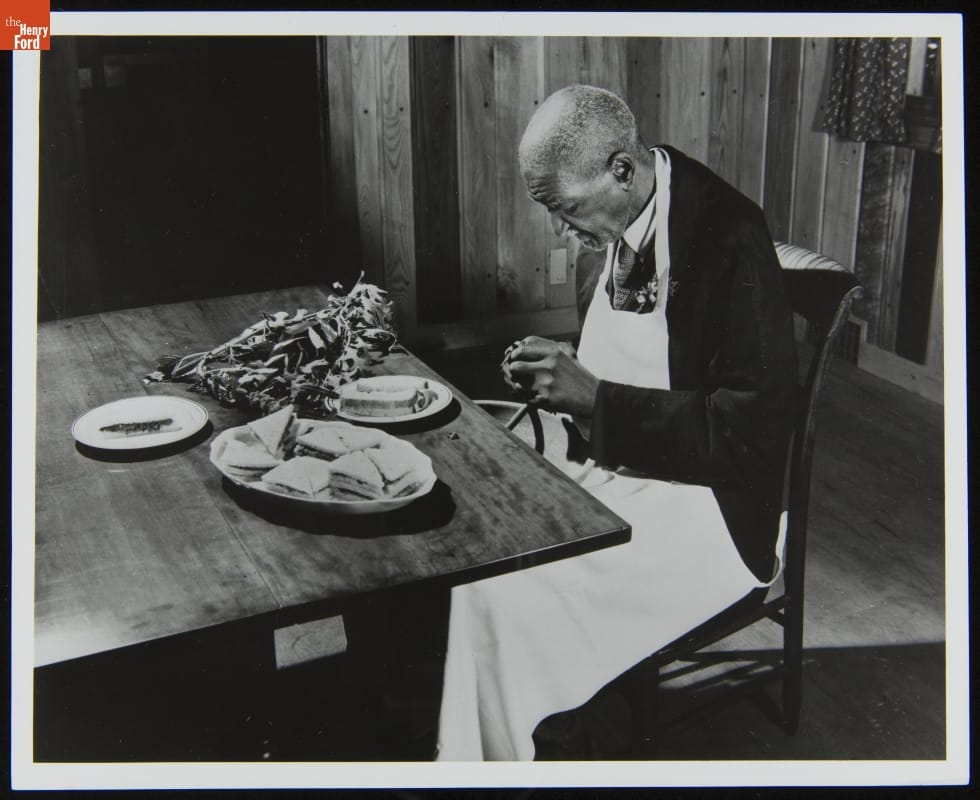

George Washington Carver would stay for two weeks and during his visit, he was given the “royal” treatment. His visit was covered extensively by the press and he made at least one formal presentation to the student of the Edison Institute at the Martha Mary Chapel. During his stay, he resided at the Dearborn Inn, but on July 21, following the dedication of the laboratory and the memorial in Greenfield Village, just to add another level of authenticity to the cabin, Carver spent the night in it.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford at the Dedication of the George Washington Carver National Laboratory, July 21, 1942. THF253993

Edsel Ford, George Washington Carver, and Henry Ford, Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF253989

George Washington Carver at fireplace in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285303

George Washington Carver seated at the table in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285305

Interior views of Carver Memorial, August, 1943. THF285309 and THF285307

The completed George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village c.1943. THF285299

Beginning in 1938, Carver began to suffer from some serious health issues. Pernicious anemia is often a fatal disease and when first diagnosed, there was not much hope for Carver’s survival. He surprised everyone by responding to the new treatments and gaining back his strength. Henry and Clara visited Tuskegee in 1938 for the first time, later, when Henry Ford heard of Carver’s illness, he sent an elevator to be installed in the laboratory where Carver spent most of his time. Carver would profusely thank Ford, calling it a “life saver”. In 1939, Carver visited the Fords at Richmond Hill and visited the school the Fords had built and named for him there. In 1941, the Fords made another visit to Tuskegee to attend the dedication of the George Washington Carver Museum.

During this time, Carver would suffer relapses, and then rebound, each time surprising his doctors. This likely had much to do with his change in travel plans in the summer of 1942. Following his visit to Dearborn, through the fall, there was regular correspondence to Henry Ford. One of the last, dated December 22, 1942, was a thank you for the pair of shoes made by the Greenfield Village cobbler. Following a fall down some stairs, George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943, he was seventy-eight years old.

Carver Memorial in its whitewashed iteration, c.1950. THF285299

It was seventy-five years ago, that George Washington Carver made his last trip to Dearborn. His legacy lives on here, and he remains in the excellent company of those everyday Americans such as Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford, who despite very ordinary beginnings, went on to achieve extraordinary things and inspire others. His fame lives on today, and even our elementary school- age guests, know of George Washington Carver and his work with the peanut.

Jim Johnson is Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford.

Sources Cited

- Bryan, Ford, Friends, Family & Forays: Scenes from the Life & Times of Henry Ford, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2002.

- Edward Cutler Oral Interview, 1955, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- Collection of correspondences between Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, 1937-1943, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- George Washington Carver Memorial Building Boxes, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- The Herald, August, 1942, The Edison Institute, Dearborn, MI

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Series | |

Themes |