Posts Tagged greenfield village history

Moving and Reconstructing Firestone Farm

Firestone Farmhouse and Firestone Barn during reconstruction in Greenfield Village, December 1984. / THF118159

Two centuries ago, in the 1820s, Peter Firestone began the construction of his new farmstead in Columbiana County, Ohio. It eventually comprised a sturdy brick home, a very large barn, and several small outbuildings. The task took him, his family, and numerous local craftsmen many years to complete. The farmhouse alone is said to have taken four years; it is possible the entire complex may have taken as many as ten years.

When The Henry Ford acquired Firestone Farmhouse and Firestone Barn in 1983, the first challenge we faced was moving them to Dearborn, Michigan, from their original location in eastern Ohio—some 200 miles away. We decided the only feasible method was to completely disassemble the buildings, pack the materials into trailers, and transport them to Greenfield Village, where we would reenact Peter Firestone's feat.

Research and Disassembly

Our project commenced in April 1983, when an architectural recording team began to measure the structures to be moved and created drawings that would be used for their reconstruction. The team noted the condition of the buildings, researched their history, and began to develop theories about the changes the structures had gone through over the years. Armed with architectural plans and documentary evidence, we began a careful probing of the buildings to uncover information about their construction.

We took paint samples from wood surfaces and analyzed them microscopically to help identify layers of paint applied over time. We also removed brick and mortar samples for chemical analysis. At this time, we discovered former stair locations, old room partition placements, blocked-up doorways, and the remnants of a fireplace in the farmhouse. Our examination of the barn revealed much about its original form and the changes made to it in the early 20th century. Our team recorded the location of mortises for missing framing members and incorporated patterns of the original construction into the drawings.

In conjunction with this work, we conducted two other types of research—archeological research and architectural field research. Evidence from an archeological dig to locate outbuildings that had once been part of the historic farm proved inconclusive, but we did uncover a large quantity of artifacts that helped establish how the farmhouse had been furnished in the past. As part of our architectural field research, we surveyed more than 200 area farmsteads. After analyzing our material, we went back to conduct an in-depth study of 25 barns resembling Firestone Barn, as well as various other 19th-century outbuildings.

We began disassembling the structures by removing and numbering interior woodwork and doors, which were then packed into trailers. Our team removed plaster and lath from ceilings and partitions. Then, we took up floorboards from all three levels of the farmhouse, numbered them, and placed them into trailers. In this same way, all the elements of the farmhouse interior and roof were disassembled and readied for shipment to Greenfield Village.

Next, restoration specialists took apart the masonry structure of the farmhouse brick by brick. They cleaned the bricks onsite and packed them with straw in shipping crates. As the brick walls came down, we removed window and door units intact. Then, the masonry specialists prepared the farmhouse’s sandstone foundation for disassembly. They numbered each stone on the interior face (which had several layers of whitewash on it) and photographed each wall surface with its numbering pattern showing. As the masons removed the stones, they again numbered each one on its top bedding surface. The stones, too, were cleaned and packed with straw in crates, and the number of each stone was listed on the outside.

Masonry restorers removed each brick from the walls of Firestone Farmhouse. After being cleaned of excess mortar, the bricks were packed with straw in the crates in the foreground. / THF149938

The barn was stripped of its 20th-century additions, siding, and roof to expose the frame of the building for disassembly. The wooden pins anchoring each timber joint had to be driven out so that the posts and beams could be taken apart in the reverse order of their assembly. Prior to removal, each timber was numbered with a color-coded plastic tag that identified its location in the frame. Timbers less than 40 feet long were loaded into trailers. Those that were longer—for example, one floor support beam that measured 68 feet—had to be shipped on a special stretch trailer.

Disassembly of Firestone barn at its original site, Columbiana County, Ohio, 1983. / THF628361, THF628363, THF628367, THF628369

Discoveries

Each stage of disassembly yielded more information about the original construction and subsequent alterations of the buildings.

In the barn we discovered the original granary and hay chute arrangements. Analysis of historic photographs and field data brought to light the "drive-through" equipment shed/corn crib that had been almost obliterated by 20thcentury alterations. We also unveiled early 19th-century changes to the structure, including a tool and storage room on the second level and subdivisions of the stalls on the first level.

The farmhouse continued to divulge more of its secrets. Evidence of major interior and exterior renovations turned up daily, as we found reused materials from the original construction in every conceivable portion of the later construction.

This bedroom doorway, which had been closed off during Firestone Farmhouse’s 1882 renovation, came to light during the disassembly process. / THF149936

We made one very exciting find while moving a section of hand-decorated plaster ceiling above the central stairway. Attached to a framing member associated with the farmhouse’s renovation was a scrap of paper inscribed, “James Maxwell Washingtonville Ohio 1882 / Harvey Firestone Columbiana Ohio 1882.” Aged 12 and 14, respectively, these boys had left a "secret" message, and we had been the lucky finders. Census research established that James Maxwell was the son of a plasterer. He was probably helping his father with interior renovation for the Firestones. Since we knew from the account book of Harvey Firestone’s father, Benjamin, that the renovation of the exterior of the farmhouse had been accomplished in 1882, the note proved conclusively that the interior renovation had been done at the same time. This helped influence our choice of 1882 as the restoration period for the entire farm.

This hidden message enabled us to precisely date Firestone Farmhouse’s 1882 renovation. / THF124772

Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village

While all this work was taking place in Ohio, we transformed Greenfield Village in anticipation of the farm's arrival. Workers cleared a seven-acre area designated as the farm site for development. We moved six buildings to new locations in the Village; eliminated four non-historic buildings from the area; constructed three new buildings for behind-the-scenes activities to replace those displaced by the farm; and relocated a portion of the railroad tracks.

By the end of 1983, four trailers, two large stacks of over-sized beams, and no fewer than 250 crates of brick and stone were all onsite awaiting the spring construction season. While planning for the entire farm restoration continued, workers began to reproduce a substantial portion of the barn that had been lost to 20th-century alterations. We purchased white oak logs, and craftsmen began hand hewing and joining timbers to recreate most of the original ground-floor framing, which had been replaced by modern materials. This process alone, excluding the actual erection of the timbers, took four craftsmen nearly three months to accomplish. Later in the project, additional components had to be created to replace portions of two sheds initially attached to the main barn. These had been drastically altered for 20th-century farming needs. The upper portions of the barn required numerous replacements and repairs, though most of this part of the frame had been unchanged from its original construction.

In May 1984, we broke ground for the foundation of both the farmhouse and barn. Throughout the summer and into the fall, the masonry shell of the farmhouse rose slowly from the foundation toward the roof line, with windows, doors, and floor framing incorporated during the process. The task of restoring each basement stone to its original location and replicating the brick bonding was tedious and time-consuming. To replace damaged bricks, we manufactured replicas in three different shades to match the originals in color variation, as well as in shape and texture. The entire masonry shell of the farmhouse was finally completed late in the fall, just as plunging temperatures threatened to stop the project. Winter weather halted most outdoor activity, and a temporary roof was placed on the building until late the next spring.

Masons set the transported stones back into Firestone Farmhouse’s new foundation. Here, the author assists by referring to composite photographs of each of the basement walls. / THF149926

The largely reproduced lower frame of the barn was erected in the summer, with repairs and minor replacements to the large upper section of the building continuing into the fall. After trial-fitting and adjusting individual portions of the upper stories, workers reassembled them in sections called “bents.” Each bent was lifted into place, then connected to another by struts and top plates to create the full frame. The erection process for the three-tier main frame lasted until December, when production of the attached sheds began. We completed roofing and siding of the main barn in the winter months as work on the remaining portions of the sheds moved offsite and indoors to escape the cold weather.

The author in May 1985 with a portion of the scale model constructed to assist in the restoration of the barn. The ramp side of the nearly completed barn is in the background. / THF149932

We restored the interior of the farmhouse during the first four months of 1985, placing each numbered floorboard, wall stud, wall plank, and door or window trim piece in its original location. At the same time, we repaired or replaced damaged materials using the same type of materials in the original construction. We applied new plaster to lathed stud walls and ceilings, as well as to the brick walls of the interior, then reinstalled additional trimwork that had covered the old plastering. Finish work then began on the interior surfaces of the farmhouse in preparation for whitewashing, painting, and papering. Carpenters moved outside at this time to restore the three porches that had been built in 1882. We finished painting the exterior in early June 1985.

With the coming of spring, we resumed outdoor work on the barn. We completed the attached sheds and massive stone ramp that leads to the upper floor of the barn, then moved our work inside. We attached plank floors with wooden pegs in the threshing area; restored the granary and tool room; and placed packed earth floors in the animal stall area on the ground level. We constructed new doors based on historic photographs, field studies, and an extant door—one of three types used for the barn.

The restoration of the farmhouse and barn did not represent a complete recreation of the Firestone farm. Additional elements helped establish the environment of an operating farm of the 1880s. We reproduced a pump house next to the farmhouse using historic photographs, archeological evidence, and field research data. We also acquired a period outhouse in Ohio, restored it, and placed it in the yard behind the farmhouse. We then erected a chicken house—modeled after examples shown in agricultural literature of the period—adjacent to the barn, as well as a fence enclosure for hogs. To complete the experience, we built more than 7,000 linear feet of fencing to match historic photographs of fields at the farm’s original site.

Over a period of almost two and a half years, we moved the Firestone farm from Ohio to Michigan and meticulously and accurately restored it to its physical condition of a century earlier. The process required an understanding of the historical record, the careful handling of tens of thousands of historic architectural objects, and the reproduction of thousands of missing elements. It may not have equaled Peter Firestone's feat 160 years earlier, but it did honor his effort, as well as that of the millions of 19th-century farmers who contributed to our country's agricultural heritage.

Blake D. Hayes is former Conservator of Historic Structures at The Henry Ford, including during the move and reconstruction of the Firestone farmstead. This post was adapted by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford, from an article in Volume 14, Number 2 of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Herald (1985).

Ohio, 1980s, 20th century, research, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Firestone family, farms and farming, conservation, collections care, by Saige Jedele, by Blake D. Hayes, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

1932 Ford V-8 Engine, No. 1. / THF101039

It’s been said that when the Ford flathead V-8 went into production in 1932, Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automobile industry—again. And the engine put the hot rod movement into high gear.

What made this engine revolutionary? It was the first V-8 light enough and cheap enough to go into a mass-produced vehicle. The block was cast in one piece, and the design was conducive to backyard mechanics’ and gearheads’ modifications.

This 1932 brochure illustrates the difference between the Ford V-8, with the cylinders and crankcase cast as a single block of iron, and a traditional V-8, built by bolting separate cylinders onto the crankcase. / THF125666

With so much at stake, you would think Henry Ford would set up his engineers tasked with the engine’s design in the most state-of-the-art facility he had at his disposal.

Not so. Instead, Ford sent a handpicked crew to Greenfield Village to gather in Thomas Edison’s Fort Myers Laboratory, which had been moved from Fort Myers, Florida, to Dearborn not long before.

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison with Fort Myers Laboratory at its original site, Fort Myers, Florida, circa 1925. / adapted from THF115782

“Henry Ford likely used the building because it provided his engineers with privacy and freedom from distraction,” said Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. “I imagine he also thought the team might be inspired by the surroundings.”

Ford’s plan worked. In just two years, Ford’s engineering crew left the lab in Greenfield Village with a final design.

Continue Reading

Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford, Ford Motor Company, manufacturing, design, engineering, engines, race cars, cars, racing, The Henry Ford Magazine

William Holmes McGuffey’s Birthplace

McGuffey’s birthplace in Greenfield Village today. / THF1969

William Holmes McGuffey’s easy-to-understand Eclectic Readers were influenced by his experiences growing up on the Pennsylvania and Ohio frontiers, as well as his family background and upbringing. His birthplace, a log home from western Pennsylvania now in Greenfield Village, is a physical representation of these experiences.

McGuffey’s Birthplace in Western Pennsylvania

Portrait of William Holmes McGuffey, 1855. / THF286352

William Holmes McGuffey’s family was Scots-Irish (or Scotch-Irish)—a group of strict Presbyterians who had migrated from the Scottish Lowlands to Ulster, in northern Ireland, over several centuries into the early 1700s. During the 1700s, many Scots-Irish emigrated to Pennsylvania, a colony that offered available land for settlement and the assurance of religious freedom. By the end of America’s colonial period, more than 30% of the population in Pennsylvania was Scots-Irish.

As early as 1760, land was almost unobtainable in the American East and many Scots-Irish headed inland to the western frontier, quickly inhabiting areas in western Pennsylvania during the 1780s and 1790s. This rapid settlement was only possible because the American government had, through treaties and sometimes military action, forced Native American tribes to move successively further west until they were pushed out of western Pennsylvania entirely. The major tribes that had inhabited the area, having migrated or been forced there from other areas during the 1700s, included the Lenni-Lenape or Delaware, the Shawnee, and the Seneca (referred to by European settlers as “Mingo”). Other tribes who might have traversed and/or built temporary villages in the area included the Huron/Wyandot, Chippewa, Mississauga, Ottawa, Mohawk, Cherokee, and Mohican.

William Holmes McGuffey’s family followed the typical migration pattern of other Scots-Irish immigrants. His paternal grandparents, William (“Scotch Billy”) and Ann McGuffey, had arrived during the last great wave of Scots-Irish immigration, sailing with their three young children from Wigtownshire, Scotland, to Philadelphia in 1774. They soon joined a community of Scots-Irish immigrants in York County, where they purchased land for a small farm. In 1789, they moved to Washington County in western Pennsylvania, where cheap land on the expanding western frontier had opened to settlers.

Here, they would once again be living among like-minded people, a community of Scots-Irish Presbyterians. Scots-Irish families, like other immigrants, did not leave all of their Old-World ideas and ways of doing things behind. They shared a similar heritage of music, language, foodways, and material culture. They also tried to establish familiar institutions in the move west—first churches, but also schools, stores, and courts of law.

McGuffey Birthplace in Greenfield Village, photographed in 2007 by Michelle Andonian. / THF53239

McGuffey’s maternal grandparents, Henry and Jane Holmes, moved to Washington County about the same time as the McGuffey family. The log home that became William Holmes McGuffey’s birthplace was constructed about 1790 on the Holmes acreage. It was likely Henry and Jane Holmes’s first-stage log home (meaning they planned to build and move to a nicer home as soon as possible). Their daughter, Anna, married Alexander McGuffey at the Holmes farmstead just before Christmas 1797, and they lived in this log structure as their first home. While living there, they had their first three children: Jane (born in 1799), William Holmes (born in 1800), and Henry (born in 1802).

In 1802—only five years after they married and moved into the log house where William Holmes McGuffey was born—Alexander and Anna McGuffey moved their young family further west, to the largely unsettled Connecticut Western Reserve area of northeastern Ohio. William Holmes McGuffey, then two years old, would complete his growing-up years on this new frontier (see “William Holmes McGuffey and his Popular Readers” for more on this).

Log Houses

During the 1840 Presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison, the log home became a romantic symbol of the frontier and the pioneer spirit, as shown in this 1840 music sheet cover. / THF256421

The log house would become an American icon, but its origins are European. Finnish and Swedish settlers are thought to have been the first people to construct horizontal log dwellings in America, in the colony of New Sweden (now Delaware) in the early 1600s. Welsh settlers carried the tradition of log construction into Pennsylvania.

Later waves of immigrants, including Swiss and Germans, brought their own variations of log dwellings. The Scots-Irish, who did not possess a log building tradition of their own, supposedly adapted a form of the stone houses from their native country to log construction, and greatly contributed to its spread across the frontier.

One of the principal advantages of log construction was the economy of tools required to complete a structure. A log structure could be raised and largely completed with as few as two to four different tools. Trees could be chopped down and logs cut to the right length with a felling axe. The sides of the logs were hewn flat with a broad axe. Notching was done with an axe, hatchet, or saw.

A closeup of the McGuffey birthplace on its original location, showing both notching and the chinking. / THF251509

The horizontal spaces or joints between logs were usually filled with a combination of materials, known as “chinking” and “daubing.” These materials were used for shutting out the driving wind, rain, and snow as well as keeping out vermin. Many different materials were used for chinking and daubing, including whatever was most conveniently at hand. Chinking usually consisted of wood slabs or stones, along with a soft packing filler such as moss, clay, or dried animal dung. Daubing, applied last, often consisted of clay, lime, and other locally available materials.

McGuffey’s Birthplace in Greenfield Village

McGuffey’s birthplace on its original site in 1932. / THF133827

Henry Ford was among the last generation of children to be educated by William Holmes McGuffey’s readers. Beginning in the 1910s, Ford purchased every copy of the readers that he could find—amassing, by the 1930s, a collection of 468 copies of 145 different editions. By the early 1930s, Ford decided to commemorate McGuffey’s impact on his education and upbringing in an even bigger way—by moving McGuffey’s humble log home birthplace to Greenfield Village.

Unfortunately, by the time Henry Ford saw McGuffey’s birthplace in western Pennsylvania in October 1932, it no longer served as a home, but had been used for many years as a “loom house” or “spinning room” and a sheep barn. The structure had largely collapsed; no walls were completely standing. But Henry Ford purchased it anyway, from a McGuffey descendant who still owned the property. Edward Cutler, Henry Ford’s architect, measured the remaining chimney foundation for later recreation, and had trees suitable to replace the missing or deteriorated logs cut down and prepared for shipment. All these parts were shipped to Dearborn in November 1932.

From January to August 1934, the home was reconstructed in the Village with some modifications. Originally a rectangular home, when completed in Greenfield Village it was approximately 16½ feet square and was ten logs high rather than nine. A shed (smokehouse) was found on the Pennsylvania site and recorded, but was not moved with the McGuffey house. The smokehouse in Greenfield Village was a replica completed at the same time as the house. By 1942, a pen with sheep had been added.

Constructing the McGuffey School in Greenfield Village, 1934. / THF98571

The William Holmes McGuffey School was a newly constructed building in Greenfield Village, built in 1934 out of logs from the Holmes family’s original barn. Among its early furnishings was a schoolmaster’s desk made from a walnut kitchen table used by the McGuffey family.

Dedication ceremonies for the McGuffey buildings took place on September 23, 1934 (the 134th anniversary of McGuffey’s birth), in Greenfield Village. Attended by McGuffey relatives and other dignitaries, the dedication ceremonies were broadcast by NBC. A memorial program was also held at the McGuffey birthplace site in Washington County, Pennsylvania, and a marker was placed there.

Interior of William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, 1954. / THF138606

For many years, William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, furnished with household goods of the period, was open for visitors touring Greenfield Village. Over time, the structure was repaired many times, but some of the choices made during these renovations—like copper sheathing, wire mesh, and Portland cement—increased the rate of the structure’s deterioration. In 1998, the building was determined to be a safety hazard and closed to visitors. Happily, as part of the Village upgrade of 2002–2003, the log structure was renovated and restored. This involved replacing logs and roof shingles and applying a new style of chinking with a non-Portland cement mortar mix.

Presenter cooking over the fireplace in the William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, 2018. / Photo courtesy of Caroline Braden

The William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace is today furnished as it might have looked in 1800–1802, the period when the McGuffey family resided there during William Holmes McGuffey’s infancy and toddlerhood. Though we have no specific information on furnishings owned by the McGuffeys during the time they lived in this home, we have excellent information on household furnishings from the same time period and geographic location, based upon probate inventories of families from Washington County, Pennsylvania. These include such furnishings as a worktable, a few mismatched chairs, iron pots for fireplace cooking, a butter churn, and kegs and barrels for storing food.

Interior of William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, showing current placement of furnishings. / Photo courtesy of Deborah Berk

The furnishings reflect the needs and personalities of its inhabitants—William Holmes’s father, Alexander; his mother, Anna; and William and his siblings. For example, in order to emphasize the influence of the religious and literate Anna, we have included a Bible and some books. Alexander is represented by men’s clothing and the shaving set on the shelf. The children’s presence is indicated by the cradle, the small stool, the diapers on the drying rack, and the toys in the cupboard.

The placement of the furnishings in the McGuffey birthplace also shows the family’s Scots-Irish background. It was the custom of this group to make the hearth the focal point of the home, with a clear path from the door to the fireplace. Rather than being put in the center of the room, the table would have been de-emphasized and placed against the wall.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. Her book, Spaces that Tell Stories: Recreating Historical Environments (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), recounts in greater detail the research, furnishings plan, and current interpretation of the William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace in Greenfield Village.

immigrants, home life, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, by Donna R. Braden

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052

The home was just as quaint inside—large open fireplaces with the mantels supported on oak beams. Heavy oak beams graced the ceilings and the roof. Spiral stone staircases led to the second floor. Morton bought the house and the two acres on which it stood under his own name from Margaret Smith in April 1929 for approximately $5000. Ford’s name was kept quiet. Had the seller been aware that the actual purchaser was Henry Ford, the asking price might have been higher.

Cotswold Cottage (probably built about 1619) as it looked when Herbert Morton spotted it, 1929–1930. / THF236020

“Perfecting” the Cotswold Look

Over the next several months, Herbert Morton and Frank Campsall, Ford’s personal secretary, traded correspondence concerning repairs and (with the best of intentions on Ford’s part) some “improvements” Ford wanted done to the building: the addition of architectural features that best exemplified the Cotswold style. Morton sent sketches, provided by builder and contractor W. Cox-Howman from nearby Stow-on-the-Wold, showing typical Cotswold architectural features not already represented in the cottage from which to choose. Ford selected the sketch which offered the largest number of typical Cotswold features.

Ford’s added features on the left cottage included a porch (a copy of one in the Cotswold village of Rissington), a dormer window, a bay window, and a beehive oven.

Cotswold Cottage, 1929–1930, showing modifications requested by Henry Ford: the beehive oven, porch, and dormer window. / THF235980

Bay window added to the left cottage by Henry Ford (shown 1929–1930). Iron casement windows were added throughout. / THF236054

The cottage on the right got a doorway “makeover” and some dove-holes. These holes are commonly found in the walls of barns, but not in houses. It would have been rather unappealing to have bird droppings so near the house!

Ford’s modifications to the right cottage—a new doorway (top) and dove-holes (bottom) on the upper wall. / THF236004, THF235988

Cotswold Cottage, now sporting Henry Ford’s desired alterations. / THF235984

Ford wanted the modifications completed before the building was disassembled—perhaps so that he could establish the final “look” of the cottage, as well as be certain that there were sufficient building materials. The appearance of the house now reflected both the early 1600s and the 1920s—each of these time periods became part of the cottage’s history. Ford’s additions, though not original to the house, added visual appeal.

The modifications were completed by early October 1929. The land the cottage stood on was transferred to the Ford Motor Company and later sold.

Cotswold Cottage Comes to America

Cotswold Cottage being disassembled. / THF148471

By January 1930, the dismantling of the modified cottage was in process. To carry out the disassembly, Morton again hired local contractor W. Cox-Howman.

Building components being crated for shipment to the United States. / THF148475

Doors, windows, staircases, and other architectural features were removed and packed in 211 crates.

Cotswold building stones ready for shipment in burlap sacks. / THF148477

The building stones were placed in 506 burlap sacks.

Cotswold barn and stable on original site, 1929–1930. / THF235974

The adjacent barn and stable, as well as the fence, were also dismantled and shipped along with the cottage.

Hauled by a Great Western Railway tank engine, 67 train cars transported the materials from the Cotswolds to London to be shipped overseas. / THF132778

The disassembled cottage, fence, and stable—nearly 500 tons worth—were ready for shipment in late March 1930. The materials were loaded into 67 Great Western Railway cars and transported to Brentford, west London, where they were carefully transferred to the London docks. From there, the Cotswold stones crossed the Atlantic on the SS London Citizen.

As one might suspect, it wasn’t a simple or inexpensive move. The sacks used to pack many of the stones were in rough condition when they arrived in New Jersey—at 600 to 1200 pounds per package, the stones were too heavy for the sacks. So, the stones were placed into smaller sacks that were better able to withstand the last leg of their journey by train from New Jersey to Dearborn. Not all of the crates were numbered; some that were had since lost their markings. One package went missing and was never accounted for—a situation complicated, perhaps, by the stones having been repackaged into smaller sacks.

Despite the problems, all the stones arrived in Dearborn in decent shape—Ford’s project manager/architect, Edward Cutler, commented that there was no breakage. Too, Herbert Morton had anticipated that some roof tiles and timbers might need to be replaced, so he had sent some extra materials along—materials taken from old cottages in the Cotswolds that were being torn down.

Cotswold “Reborn”

In April 1930, the disassembled Cotswold Cottage and its associated structures arrived at Greenfield Village. English contractor Cox-Howman sent two men, mason C.T. Troughton and carpenter William H. Ratcliffe, to Dearborn to help re-erect the house. Workers from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant also came to assist. Reassembling the Cotswold buildings began in early July, with most of the work completed by late September. Henry Ford was frequently on site as Cotswold Cottage took its place stone-by-stone in Greenfield Village.

Before the English craftsmen returned home, Clara Ford arranged a special lunch at the cottage, with food prepared in the cottage’s beehive oven. The men also enjoyed a sight-seeing trip to Niagara Falls before they left for England in late November.

By the end of July 1930, the cottage walls were nearly completed. / THF148485

On August 20, 1930, the buildings were ready for their shingles to be put in place. The stone shingles were put up with copper nails, a more modern method than the wooden pegs originally used. / THF148497

Cotswold barn, stable, and dovecote, photographed by Michele Andonian. / THF53508

Free-standing dovecotes, designed to house pigeons or doves which provided a source of fertilizer, eggs, and meat, were not associated with buildings such as Cotswold Cottage. They were found at the homes of the elite. Still, for good measure, Ford added a dovecote to the grouping about 1935. Cutler made several plans and Ford chose a design modeled on a dovecote in Chesham, England.

Henry and Clara Ford Return to the Cotswolds

The Lygon Arms in Broadway, where the Fords stayed when visiting the Cotswolds. / THF148435, detail

As reconstruction of Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village was wrapping up in the fall of 1930, Henry and Clara Ford set off for a trip to England. While visiting the Cotswolds, the Fords stayed at their usual hotel, the Lygon Arms in Broadway, one of the most frequently visited of all Cotswold villages.

Henry (center) and Clara Ford (second from left) visit the original site of Cotswold Cottage, October 1930. / THF148446, detail

While in the Cotswolds, Henry Ford unsurprisingly asked Morton to take him and Clara to the site where the cottage had been.

Cotswold village of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1930. / THF148440, detail

At Stow-on-the-Wold, the Fords called on the families of the English mason and carpenter sent to Dearborn to help reassemble the Cotswold buildings.

Village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds. / THF148437, detail

During this visit to the Cotswolds, the Fords also stopped by the village of Snowshill, not far from Broadway, where the Fords were staying. Here, Henry Ford examined a 1600s forge and its contents—a place where generations of blacksmiths had produced wrought iron farm equipment and household objects, as well as iron repair work, for people in the community.

The forge on its original site at Snowshill, 1930. / THF146942

A few weeks later, Ford purchased the dilapidated building. He would have it dismantled, and then shipped to Dearborn in February 1931. The reconstructed Cotswold Forge would take its place near the Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village.

To see more photos taken during Henry and Clara Ford’s 1930 tour of the Cotswolds, check out this photograph album in our Digital Collections.

Cotswold Cottage Complete in Greenfield Village—Including Wooly “Residents”

Completed the previous fall, Cotswold Cottage is dusted with snow in this January 1931 photograph. Cotswold sheep gather in the barnyard, watched over by Rover, Cotswold’s faithful sheepdog. (Learn Rover's story here.) / THF623050

A Cotswold sheep (and feline friend) in the barnyard, 1932. / THF134679

Beyond the building itself, Henry Ford brought over Cotswold sheep to inhabit the Cotswold barnyard. Sheep of this breed are known as Cotswold Lions because of their long, shaggy coats and faintly golden hue.

Cotswold Cottage stood ready to welcome—and charm—visitors when Greenfield Village opened to the public in June 1933. / THF129639

By the Way: Who Once Lived in Cotswold Cottage?

Cotswold Cottage, as it looked in the early 1900s. From Old Cottages Farm-Houses, and Other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District, 1905, by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber. / THF284946

Before Henry Ford acquired Cotswold Cottage for Greenfield Village, the house had been lived in for over 300 years, from the early 1600s into the late 1920s. Many of the rapid changes created by the Industrial Revolution bypassed the Cotswold region and in the 1920s, many area residents still lived in similar stone cottages. In previous centuries, many of the region’s inhabitants had farmed, raised sheep, worked in the wool or clothing trades, cut limestone in the local quarries, or worked as masons constructing the region’s distinctive stone buildings. Later, silk- and glove-making industries came to the Cotswolds, though agriculture remained important. By the early 1900s, tourism became a growing part of the region’s economy.

A complete history of those who once occupied Greenfield Village’s Cotswold Cottage is not known, but we’ve identified some of the owners since the mid-1700s. The first residents who can be documented are Robert Sley and his wife Mary Robbins Sley in 1748. Sley was a yeoman, a farmer who owned the land he worked. From 1790 at least until 1872, Cotswold was owned by several generations of Robbins descendants named Smith, who were masons or limeburners (people who burned limestone in a kiln to obtain lime for mixing with sand to make mortar).

As the Cotswold region gradually evolved over time, so too did the nature of some of its residents. From 1920 to 1923, Austin Lane Poole and his young family owned the Cotswold Cottage. Medieval historian, fellow, and tutor at St. John’s College at Oxford University (about 35 miles away), Poole was a scholar who also enjoyed hands-on work improving the succession of Cotswold houses that he owned. Austin Poole had gathered documents relating to the Sley/Robbins/Smith families spanning 1748 through 1872. It was these deeds and wills that revealed the names of some of Cotswold Cottage’s former owners. In 1937, after learning that the cottage had been moved to Greenfield Village, Poole gave these documents to Henry Ford.

In 1926, Margaret Cannon Smith purchased the house, selling it in 1929 to Herbert Morton, on Henry Ford’s behalf.

“Olde English” Captures the American Imagination

At the time that Henry Ford brought Cotswold Cottage to Greenfield Village, many Americans were drawn to historic English architectural design—what became known as Tudor Revival. The style is based on a variety of late Middle Ages and early Renaissance English architecture. Tudor Revival, with its range of details reminiscent of thatched-roof cottages, Cotswold-style homes, and grand half-timbered manor houses, became the inspiration for many middle-class and upper-class homes of the 1920s and 1930.

These picturesque houses filled suburban neighborhoods and graced the estates of the wealthy. Houses with half-timbering and elaborate detail were often the most obvious examples of these English revival houses, but unassuming cottage-style homes also took their place in American towns and cities. Mansion or cottage, imposing or whimsical, the Tudor Revival house was often made of brick or stone veneer, was usually asymmetrical, and had a steep, multi-gabled roof. Other characteristics included entries in front-facing gables, arched doorways, large stone or brick chimneys (often at the front of the house), and small-paned casement windows.

Edsel Ford’s home at Gaukler Pointe, about 1930. / THF112530

Henry Ford’s son Edsel and his wife Eleanor built their impressive but unpretentious home, Gaukler Pointe, in the Cotswold Revival style in the late 1920s.

Postcard, Postum Cereal Company office building in Battle Creek, Michigan, about 1915. / THF148469

Tudor Revival design found its way into non-residential buildings as well. The Postum Cereal Company (now Post Cereals) of Battle Creek, Michigan, chose to build an office building in this centuries-old English style.

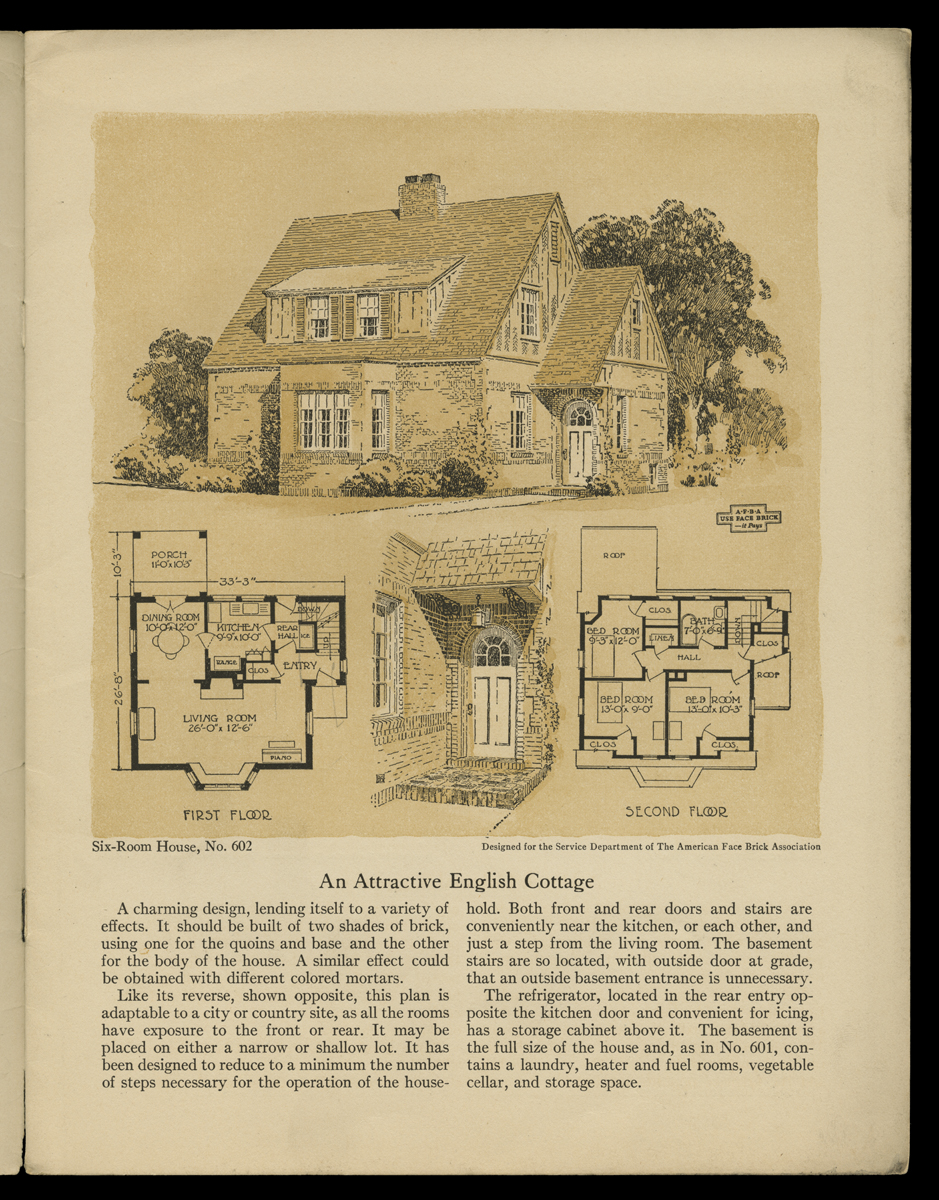

Plan for “An Attractive English Cottage” from the American Face Brick Association plan book, 1921. / THF148542

Plans for English-inspired homes offered by Curtis Companies Inc., 1933. / THF148549, THF148550, THF148553

Tudor Revival homes for the middle-class, generally more common and often smaller in size, appeared in house pattern books of the 1920s and 1930s.

Sideboard, part of a dining room suite made in the English Revival style, 1925–1930. / THF99617

The Tudor Revival called for period-style furnishings as well. “Old English” was one of the most common designs found in fashionable dining rooms during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christmas card, 1929. / THF4485

Even English-themed Christmas cards were popular.

Cotswold Cottage—A Perennial Favorite

Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF53489

Henry Ford was not alone in his attraction to the distinctive architecture of the Cotswold region and the English cottage he transported to America. Cotswold Cottage remains a favorite with many visitors to Greenfield Village, providing a unique and memorable experience.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Cotswold Cottage Tea

- Interior of Cotswold Cottage at its Original Site, Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England, 1929-1930

- Cotswold Cottage

home life, design, farm animals, travel, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller

| “The fact that Webster dwelt and worked on his dictionary there gives this structure singular historic interest…. That all this must disappear shortly before the crowbars of the wreckers is a matter of genuine regret…” —J. Frederick Kelly, New Haven resident and architect, quoted in New Haven Register, July 20, 1936 |

Article from the New Haven Register, New Haven, Connecticut, July 20, 1936. / THF624813

In the mid-1930s, Yale University, owner of the Noah Webster Home on Temple Street in New Haven, Connecticut, decided this former home of one of its notable alumni needed to be torn down. It was the Depression, and Yale’s financial situation required some retrenchment. Tearing down the Webster house, along with eleven other Yale-owned homes, would cut the university’s tax bill and save the expense of maintenance, while providing space for new construction better suited to the university’s needs.

The house came very near to being demolished.

In this comfortable home, completed in 1823 at Temple and Grove streets, Noah Webster had enjoyed an active family life, written many of his publications, and completed his ultimate life’s work—America’s first dictionary. Noah and Rebecca Webster had moved to New Haven in their later years to be near family and friends, as well as the library at nearby Yale College. While living in this house, Webster published his famous American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828.

Silhouette of Noah and Rebecca Webster by Samuel Metford, 1842. / THF119764

What happened to the house after the deaths of Noah in 1843 and Rebecca in 1847? For the next seven decades, the Temple Street house was filled with new generations of Webster descendants and their relations.

The Trowbridge Era

After Noah Webster’s death in 1843, the house became part of Webster’s estate. In his will, his wife Rebecca received the lifetime use of the Temple Street house. In March 1849, executors of the Webster estate, William Ellsworth (a son-in-law) and Henry White, deeded the property to Henry Trowbridge, Jr., a merchant who sold goods imported from the Far East and a director of the New Haven Bank. (Trowbridge took out a mortgage on the house in 1850, probably to compensate the estate for the value of the house.) Trowbridge had married Webster granddaughter Mary Southgate in 1838. Mary had been raised by Noah and Rebecca Webster and had grown up in the Temple Street house. Henry and Mary Trowbridge had six children: five daughters as well as a son who died young. Mary Southgate Trowbridge passed away in May 1860 of tuberculosis at the age of 41.

In 1861, Henry Trowbridge married again, to Sarah Coles Hull. Their son Courtlandt, born in 1870, was the only surviving child of the marriage.

About 1870, prosperous Henry Trowbridge decided to remodel the house, adding a wealth of “updates” in the then-fashionable Victorian style. These included five bay windows, as well as marble fireplace mantles, plaster ceiling medallions, exterior and interior doors, and elaborately carved walnut woodwork on the first floor. Trowbridge also lengthened the first-floor windows and built a brick addition on the back.

Noah Webster Home showing Victorian-era changes, including the bay windows and addition at the rear of the home. Top photo taken about 1927; bottom photo, in 1936. / THF236369, THF236375

Over the years, the house was filled with the rhythms of everyday life and the comings and goings of family. Nine Trowbridge children grew up there—six of them were born in the house and three of them died there. Daughters married and moved out. One Trowbridge daughter made two long-distance visits home during the years she and her merchant husband lived in Hong Kong. Another returned home for a time as a widow with a young child. In the 1910s, during the final years of Trowbridge ownership, the widowed Sarah lived in the house with her son Courtlandt, his wife Cornelia, and their three children.

Webster Home—perhaps a bit overgrown—about 1912. / THF236373

In 1918, the year following his mother’s death, 68-year-old Courtlandt Trowbridge sold the Temple Street house in which he had lived since birth “for the consideration of one dollar,” deeding the property to the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, located a block from the Webster house on Grove Street. Courtlandt, a Sheffield graduate, then moved to Washington, a rural village in northwest Connecticut, along with his wife, Sarah, and youngest son, Robert.

From Family Home to College Dorm

Postcard, Sheffield Scientific School, Yale College, 1915-1920. / THF624831

Sheffield Scientific School offered courses in science and engineering. Following World War I, its curriculum gradually became completely integrated with Yale University’s—undergraduate courses were taught at Sheffield from 1919 to 1945, coexisting with Yale’s science programs. (Sheffield would cease to function as a separate entity in 1956.) The Sheffield Scientific School used the Webster house as a men’s dormitory for freshmen for almost 20 years.

Postcard, Vanderbilt-Sheffield dormitories on Chapel Street in New Haven, about 1909. / THF624833

The Webster house wasn’t Sheffield’s only dormitory, though. The impressive Vanderbilt-Sheffield dorms, dating from the early 1900s, served most of Sheffield’s students. The Noah Webster Home provided some additional space for freshmen to live.

A view of Temple street about 1927, during the time Yale University used the Webster house (shown at far right) as a dormitory. / THF236367

In 1936, Yale decided that retaining the “non-revenue-bearing” house was not financially viable for the university. It was no longer needed as a dorm because of the construction of Yale’s Dwight College, opened in September 1935. Removing the Webster home would also provide space for growth for the university. (The site would become part of Yale’s Silliman College.)

A Timely Rescue

In early July 1936, Yale University was granted permission to demolish the house. (The louvered, elliptical window was to go to the Yale Art School.) The house was sold to Charles Merberg and Sons, a wrecking company. But there were attempts to save the home. Soon after Yale University was granted a permit on July 3 to tear down the house, the local newspaper, the New Haven Register, began a campaign to save it. New Haven resident Arnold Dana, a retired journalist, offered to contribute to a fund to preserve the house, but no additional offers of funds came. For several weeks, articles appeared in newspapers in New York and other large cities on the subject.

Initial interest in preserving the building by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA, now Historic New England) waned because of the Victorian-era changes. William Sumner Appleton, the society’s founder and a chief force behind the preservation of many historic buildings in New England, thought the building might make an interesting museum if a private individual would take on the project. Appleton said that SPNEA had no funds to do so.

J. Frederick Kelly, a New Haven resident, architect, and author of books on early Connecticut architecture, noted the building’s historical significance and commented on its architecture: “…the fine proportion and delicate scale of the Temple Street façade mark it as one of unusual distinction. The design of the gable … contains a very handsome elliptical louvre … an outstanding feature that has no counterpart in the East so far as I am aware.”

Telegram to Edsel Ford concerning the imminent demolition of the Noah Webster Home in New Haven, Connecticut. / THF624805

On July 29, R.T. Haines Halsey sent a telegram to Edsel Ford. Halsey let Edsel know that the Webster house was “in the hands of wreckers” and that it would fit in well with “your father’s scheme” for Greenfield Village. Immediate action was needed to save the house.

1924 postcard, American wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, built to display American decorative arts from the 1600s to the early 1800s. / THF148348

Halsey, a retired New York City stockbroker, was a collector of decorative arts who was instrumental in the opening of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City in 1924. In the 1930s, Halsey had become a research assistant in the Stirling Library at Yale University. Halsey may have chosen to contact Henry through Edsel because of Edsel’s interest in art and involvement with the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

On July 27, Ralph J. Sennott, manager of the Wayside Inn in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, a historic inn restored by Henry Ford, sent Ford a letter. (Perhaps it reached Ford about the time that Halsey’s telegram did.) Sennott also made Ford aware that the Webster home was in the hands of the wrecking company and that the building needed to be removed by September 1. The wrecker was willing to sell the house, but demolition work was to begin August 3. Henry Ford paid a $100 deposit on the house on August 2 to prevent demolition going forward. Ford was given until September 15 to make his final decision on acquiring the building.

Henry Ford arrived in New Haven on September 10 to see the Webster home in person. According to Lewis Merberg of the wrecking company, Ford appreciated the building for its historical significance more than for its “antiquity.” Noah Webster likely would have appealed to Ford as the author of the popular “Blue-Backed Speller,” used by many early American schools. Ford completed the purchase, paying about $1000 for the home.

Letter from Harold Davis of the Historic American Buildings Survey to Henry Ford, September 14, 1936. / THF624811

Noting Ford’s interest in the building, Harold Davis, the Connecticut district officer of the Historic America Building Survey, made Ford aware that the organization—whose purpose it was to measure and record historic buildings—had documented the Webster house in 1934. Ford acquired copies of these drawings, which were available at the Library of Congress.

The Noah Webster Home Moves to Dearborn

When Edward Cutler, the man responsible for moving and reassembling buildings in Greenfield Village for Henry Ford, arrived in New Haven in mid-September, wreckers had already removed windows and other parts of the house. The interior was not in the best state of repair—likely a little worse for wear after almost 20 years serving as home to college freshmen. Additional documentation of the house was needed before a wrecking crew disassembled the building under Edward Cutler’s direction. Cutler took more measurements. More photos of the home’s exterior and interior would assist with its reassembly in Greenfield Village.

Edward J. Cutler made detailed drawings of the house before it was dismantled. / THF132776

Image of the back of the Webster home taken in 1936 by a local New Haven photographer, perhaps at the request of Henry Ford or one of his representatives. / THF236377

Interior of house, view from the dining room looking towards the bay window in the sitting room. / THF236381

Edsel’s son Henry Ford II, then a Yale freshman, posed in front of the Noah Webster Home during its dismantling in October 1936. / THF624803

With this move, the Noah Webster Home would shed some of its Victorian-era “modernizing.” Cutler removed the four second-floor bay windows added during the Trowbridge renovation. He did retain some Trowbridge updates—exterior and interior doors, interior architectural details, and the first-floor bay window.

In October 1936, the Webster house was dismantled and packed up in about two weeks, according to Ed Cutler. Then it was shipped to Dearborn.

Webster Home reassembled in Greenfield Village, September 1938. / THF132717

Reassembly in Greenfield Village took about a year. In June 1937, workmen broke ground for the foundation of the home. By the end of December, most of the exterior work had been completed. Progress on the interior continued through the winter months. By July 1938, finishing touches were being added to the house.

Edison Institute High School girls prepare a meal in the Webster kitchen, 1942. THF118924

Until 1946, high school girls from the Edison Institute Schools used the Noah Webster Home as a live-in home economics laboratory—a modern kitchen was provided in the brick addition built on the back of the home. Henry Ford had opened the school on the campus of his museum and village in 1929.

Webster dining room in 1963. / THF147776

The Noah Webster Home finally opened to the public for the first time in 1962, telling the story of Webster and America’s first dictionary. Yet the Webster house was furnished to showcase fine furnishings in period room-like settings, rather than reflecting a household whose elderly inhabitants started housekeeping decades before.

Noah Webster Home Today

Noah Webster Home in Greenfield Village. / THF1882

In 1989, after much research on the house and the Webster family, museum staff made the decision to return the entire home to its original appearance during the Websters’ lifetime. The remaining Victorian additions were removed, including the first-floor bay window, interior woodwork, and interior doorways added during the Trowbridge era.

Noah Webster Home sitting room after 1989 reinstallation. / THF186509

Webster family correspondence and other documents painted a picture of a household that included not only family activities, but more public ones as well. Based on this research, curators created a new furnishings plan for the reinstallation. Now visitors could imagine the Websters living there.

Pay the Websters a Visit

Whew—close call. In 1936, the Noah Webster Home was saved in the nick of time.

Now that you know “the rest of the story,” stop by the Webster Home in Greenfield Village. Enjoy this immersive look into the past and its power to inspire us today. Hear the story of the Websters’ lives in this home during the 1830s, learn about Noah’s work on America’s first dictionary and other publications, and experience the furnished rooms that give the impression that the Websters still live there today.

For more on the Noah Webster Home, see “The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner.”

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Noah Webster Home, Henry Ford, home life, by Jeanine Head Miller, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

Postcard, Aerial View of Greenfield Village, 1940 / THF132774

Henry Ford’s idea of re-creating a historic village in Dearborn, Michigan, began to take shape when he restored his own birthplace (1919) and childhood school (1923) on their original sites. In 1926, he proceeded with a plan to create his own historic village, choosing a plot of land in the midst of Ford Motor Company property and beginning to acquire the buildings that would become part of Greenfield Village.

One of Henry Ford’s earliest ideas for Greenfield Village was to have a central green or “commons,” based upon village greens he saw in New England. Ford envisioned a church and town hall flanking the ends of his Village Green. He couldn’t find exactly what he wanted, so he had them designed and built on site in Greenfield Village.

Martha-Mary Chapel

Martha-Mary Chapel / THF1966

The design for Martha-Mary Chapel was based on a much larger Universalist church in Bedford, Massachusetts. It was one of six nondenominational chapels that Ford erected. This was the first and only one built of brick.

Ford named the chapel after his mother, Mary Litogot Ford, and his wife Clara’s mother, Martha Bench Bryant. The Martha-Mary Chapel has been used for wedding ceremonies since 1935, as shown here.

First Wedding Held in Martha-Mary Chapel in Greenfield Village, 1935 / THF132820

The bell up in the tower, likely cast during the 1820s, is attributed to Joseph Revere & Associates of Boston, Massachusetts—a foundry inherited by Joseph from his more famous father, Paul Revere.

Bell, Cast by Joseph Warren Revere, circa 1834 / THF129606

Town Hall

Town halls were the places where local citizens came together to participate in town meetings. Town Hall in Greenfield Village is patterned after New England public meeting halls of the early 1800s.

Town Hall in Greenfield Village, September 2007 (Photographed by Michelle Andonian) / THF54040

These buildings also became gathering places for political elections, theatrical performances, and social events. We have often recreated the types of activities that might have appeared in town halls of the past, such as this 2007 performance.

Ragtime Street Fair in Greenfield Village, July 2007 (Photographed by Michelle Andonian) / THF52067

Scotch Settlement School

Henry Ford also decided he needed a schoolhouse for his Village Green. This one-room school—which he himself attended when he was a boy back in the 1870s—was from the so-called Scotch Settlement in Dearborn Township. Here it is on its original site in 1896.

Group outside Scotch Settlement School at Its Original Site, Dearborn Township, Michigan, 1896 / THF245422

Scotch Settlement School had been one of Henry Ford’s first restoration projects. In 1923, he had restored the school and operated it on its original site as an experimental pre-school—shown here around 1926.

Scotch Settlement School at Its Original Site in Dearborn Township, Michigan, circa 1926 / THF115902

Once in Greenfield Village, this school served as the first classroom for the Edison Institute school system that Henry Ford started in September 1929—an experimental combination of progressive education and “learning by doing.”

Henry Ford with Students outside Scotch Settlement School in Greenfield Village, 1929 / THF96582

Eagle Tavern

Ford thought a historic inn would make a nice addition to his Village Green. In 1927, he purchased this old 1830s-era inn from Clinton, Michigan—shown here on its original site in 1925. Even though this was never its name, he called it Clinton Inn.

Eagle Tavern at Its Original Site, Clinton, Michigan, 1925 / THF237252

Clinton Inn first served as a cafeteria for students attending the Edison Institute schools. When Greenfield Village opened to the public in 1933, it was the starting point for carriage tours. Later, it became a lunchroom for visitors, as shown below.

Visitors Lunching at the Clinton Inn (now Eagle Tavern), Greenfield Village, 1958 / THF123749

When we decided to turn Clinton Inn into a historic dining experience, we undertook new research. We found that a man named Calvin Wood ran this inn in 1850 and called it Eagle Tavern. Today, we recreate the food, drink, and ambience of that era.

Eagle Tavern in Greenfield Village, October 2007 / Photographed by Michelle Andonian / THF54291

You can learn more about Eagle Tavern in this episode of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, this blog post about creating the historic dining experience in Greenfield Village, and this blog post about our research and interpretation of drinking at Eagle Tavern. Also check out this blog post I wrote on how our research changed the interpretation of five Village buildings, including Eagle Tavern.

J.R. Jones General Store

What would a village green be without a general store? The J.R. Jones General Store was originally located in the village of Waterford, Michigan. Here it is on its original site in 1926, just before being moved to Greenfield Village.

J.R. Jones General Store (Just Before the Move to Greenfield Village), Original Site, Waterford, Michigan, 1926 / THF126117

We decided to focus upon the era of James R. Jones, who operated this store from 1882 to 1888. During that time, Jones sold everything from coffee and sugar to fabrics and trims to farm tools and hardware. No wonder it was called a general store!

J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, September 2007 (Photographed by Michelle Andonian) / THF53762

Check out more content about the J.R. Jones General Store on this episode of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation and the related content on our web page.

Logan County Courthouse

This courthouse, from Postville (later renamed Lincoln), Illinois, is not just any courthouse! From 1840 to 1847, Abraham Lincoln was one of several lawyers who practiced law here as part of the 8th Judicial Circuit. Later, it was a private residence, as shown here about 1900.

Group outside Logan County Courthouse at Its Original Site, Lincoln, Illinois, circa 1900 / THF238618

Lincoln thrived on the judicial circuit—handling all sorts of cases, representing different types of people, and getting to know local residents. All these experiences helped prepare him for his future role as America’s sixteenth president.

Lithograph Portrait of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 / THF11619

To Henry Ford, Abraham Lincoln embodied the ideals of the self-made man. Ford searched for a way to memorialize Lincoln’s accomplishments. When he learned of this courthouse, he obtained it, then had it dismantled and reconstructed on his Village Green.

"First Court House of Logan County Where Abraham Lincoln Practiced Law, Lincoln, Ill.," 1927 Postcard / THF121352

After the courthouse was reconstructed in Greenfield Village, Ford filled the building with Lincoln memorabilia. The chair he subsequently purchased, in which President Lincoln had been assassinated, is visible inside a glass case in this 1954 photograph.

Logan County Courthouse in April 1954, Showing the Abraham Lincoln Chair Then on Exhibit in Greenfield Village / THF121385

Today, this chair can be found in the With Liberty and Justice For All exhibition inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Chair Used by Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, on Exhibit at Henry Ford Museum, June 2007 / THF51751

You can learn more about Abraham Lincoln’s life as a traveling circuit-riding lawyer by checking out this article.

Dr. Howard's Office

This country doctor’s office completes the historic buildings located around the Village Green today. Acquired after Henry Ford’s time, it was moved to this location in 2003.

Dr. Howard's Office / THF1696

Dr. Alonson B. Howard was a country doctor practicing medicine near Tekonsha, Michigan, from 1852 to 1883. Dr. Howard would have attended to everything from pregnancies to toothaches to chronic diseases such as kidney disease and tuberculosis.

Portrait of Dr. Alonson B. Howard, 1865-1866 / THF109611

The building, originally constructed in 1839 as a one-room schoolhouse, was conveniently located in the front yard of the Howard family farm. So, when the school moved to a new building, Dr. Howard took over this building as his office.

Dr. Howard's Office at its original site, Tekonsha, Michigan, March 1956 / THF237140

After Dr. Howard’s death in 1883, his wife Cynthia padlocked the building and there it remained—virtually intact—until removed to Greenfield Village between 1959 and 1961. It opened to the public in 1963.

Interior of Dr. Howard's Office at its original site, Tekonsha, Michigan, March 1956 / THF237188

You can learn more about Dr. Howard’s life and work in this blog post.

Check out The Henry Ford Official Guidebook and Telling America’s Story: A History of The Henry Ford for more about the Village Green and the buildings surrounding it.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

#THFCuratorChat, Scotch Settlement School, J.R. Jones General Store, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Eagle Tavern, Dr. Howard's Office, by Donna R. Braden

Server shows off an array of pastries at Eagle Tavern, 2007. Photograph by Michelle Andonian. / THF54295

Server shows off an array of pastries at Eagle Tavern, 2007. Photograph by Michelle Andonian. / THF54295

April 1, 1982, was a momentous day in Greenfield Village! That was the day that Eagle Tavern opened to the public. It was our first historic dining experience—the result of months of research, recipe selection and testing, and interpretive planning. How did all this come about?

Historical presenters and food service staff pose in front of Eagle Tavern to celebrate the new dining experience, 1982. / THF237355

The Food Committee

It started when we took a chance on a young museum leader named Harold Skramstad, who became our president in 1981. Faced with a severe financial crisis at the time, Skramstad built a case around our “world-class” status and “unique historical resources.” This led to the creation of our first mission statement, which focused upon the process of change in America from a rural agricultural society to an urban industrial nation. Following that, Skramstad created several task forces and committees, each charged with developing plans to carry out our mission through a variety of public programs. This included the mysteriously named Food Committee. It turned out that this committee—comprised of curators, food service staff, and interpretation specialists—was charged with exploring ways to bring our food offerings in line with our overall interpretive framework.

Food vendor in Greenfield Village. / THF133689

Soon, new food experiences began to appear. Through the Food Committee’s collaborative efforts, vendors hawked fruit and penny candy from rolling carts like those that had been seen on urban street corners a century ago. At the Covered Bridge Lunch Stand (now Mrs. Fisher’s), visitors could partake of turn-of-the-century picnic lunches. With the help of diner expert Richard Gutman—who informed us that we possessed the last remaining lunch wagon in existence—the Owl Night Lunch Wagon was overhauled to look more like a late-19th-century lunch wagon, featuring a more historic menu. But Eagle Tavern became our “crown jewel,” as we proposed turning this historic inn into a sit-down full-service restaurant with period food and drink.

What had the building been like before this?

Clinton Inn

Ella Smith, the final owner, in front of the inn on its original site in Clinton, Michigan, circa 1905. / THF110475

In 1927—searching for a stagecoach tavern for his Village Green—Henry Ford found and purchased this imposing 1830s-era inn. From Clinton, Michigan, it was situated along what once had been the main stagecoach road between Detroit and Chicago. Over the years, the inn had gone through several proprietors and name changes, from Parks Tavern to Eagle Tavern to the Union Hotel to Smith’s Hotel. When Henry Ford had the building reconstructed in Greenfield Village, he gave it the generic name Clinton Inn.

Carriages waiting for passengers at Clinton Inn. / THF120768

From 1929 into the 1950s, the building served as a cafeteria for students attending the Edison Institute schools. Ford enlarged the back of the structure for that purpose. When Greenfield Village officially opened to the public in 1933, Clinton Inn became the starting point for public carriage tours.

1950 calendar for Greenfield Village, featuring Clinton Inn. / THF8882

In the 1950s, the building transitioned from a student lunchroom to a public cafeteria. That was still its use when I first started working at The Henry Ford (then called Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village) in 1977. Also when I started, Clinton Inn’s so-called “colonial kitchen” was used for fireplace cooking classes as part of the institution’s Adult Education Program.

Why Eagle Tavern?

Why did we choose the Eagle Tavern era to interpret? To establish a date for the historic dining experience, we looked to primary sources, as we do when we research all of our historic structures. These sources, which help us uncover the esoteric details of the past, included probate records, property deeds, tax and census records, and local newspapers. Through this research, we found that a farmer named Calvin Wood ran this tavern from 1849 to 1854, with his wife Harriet, Harriet’s daughter Irene, and additional hired help from town or the neighboring countryside. In keeping with the patriotic spirit of the time, Wood named the place Eagle Tavern.

We decided that we liked this early 1850s date. Not only did we have decent documentation on Calvin Wood, but it was also an interesting era for changes in cooking ingredients and cookbooks (both more available than before) as well as public dining practices and customs (toward more choices for individual diners, better table etiquette, more formalized meals and menus, and more specialized table settings).

The 1850s date also dovetailed with our new mission statement—about change over time—in larger ways that were transforming the entire nation at the time. These included social movements like temperance, abolition, and women’s rights; advancements in transportation, from horse-drawn vehicles to speedy railroads; and improved communication networks, as the telegraph swiftly brought the latest news to the public. Significant national events like the California Gold Rush and the Mexican War were also impacting many people’s lives.

A variety of horse-drawn vehicles passing in front of a Middletown, Connecticut, tavern, 1842–47. / THF204148

Michigan Central Railroad car, 1848. / THF147798

Researching the Food

My primary task in creating the Eagle Tavern dining experience was to find out what and how people ate during this era. I delved deeply into period sources looking for clues to these questions, including travelers’ accounts, etiquette books, merchants’ account books, newspaper ads, and historical reminiscences.

Within these sources, I found several quite eye-opening entries, like that of Isabella Bird, a British traveler who described this meal placed in front of her at a Chicago hotel in 1856: “…eight boiled legs of mutton, nearly raw; six antiquated fowls, whose legs were of the consistency of guitar-strings; baked pork with “onion fixings,” the meat swimming in grease; and for vegetables, yams, corn-cobs, and squash. A cup of stewed tea, sweetened by molasses, was at each plate…The second course consisted exclusively of pumpkin-pies.”

It’s probably good that we didn’t take these accounts completely literally when we developed the Eagle Tavern dining experience!

From these research sources, I learned that tavern fare would have come from a combination of local farms (especially, in this case, Calvin Wood’s own farm), from the fields and woods of the surrounding area, and using ingredients that would have been purchased from local merchants.

A cold plate featuring chicken salad, pictured in the 1988 Eagle Tavern Cookbook. / THF121002

The primary components of a tavern meal would have consisted of meat, vegetables and fruits (in various forms), and breadstuffs. Meat was the predominant component of the tavern meal, served in much greater quantity than today. Often, two or more meats were served at one meal. Pork, the staple food of many midwestern settlers, was the most popular meat, served in a variety of forms—including roasted, salted, baked, and as bacon, smoked ham, sausage, or spareribs. Chickens, easy to raise on farms, lent themselves to many dishes. They also could supply eggs. In fact, Lansing Swan, traveling through Sturgis, Michigan, in 1841, wrote: “We had an excellent dinner, warm cakes, tea, etc. bacon and eggs. I have eaten them until I am ashamed to see a hen and can hardly look a respectable porker in the face.”

Beef contributed to a portion of the tavern meals, as did wild game and fish from local lakes and rivers. Oysters were also popular at the time, packed on ice and transported in barrels from the East coast.

An array of vegetables for Eagle Tavern dishes, pictured in the 1988 Eagle Tavern Cookbook. / THF121001

As for vegetables, root crops lasted throughout the year and they stored easily. Potatoes were especially popular, as described in this southern Michigan meal by Charles Hoffman in 1833: “…hot rolls, tea, large pieces of pork swimming in its gravy, and a plate of potatoes that pulverized when you touched them.” Cabbage, onions, turnips, and carrots were other root crops frequently found in the research. Less hardy vegetables, like tomatoes and cucumbers, were served in season or preserved as catsups, sauces, or pickles. Pumpkins, squash, and corn were usually served in season or preserved for later use.

Fruits were served fresh in season, dried, or made into preserves, sauces, or pickles. Of these, apples were most frequently used as they were incredibly versatile—preserved, cooked, or baked into numerous dishes. Peaches, pears, apricots, grapes, and berries of all sorts were also found in the accounts. Wild strawberries were specifically called out several times by traveler Lansing Swan, in 1841. In Ypsilanti, Swan “got an excellent supper for 25 cents and many large delicious strawberries with rich cream.” Farther west, in Jackson, he happily remarked that he was, “Just in time for tea with strawberries and cream.” In Niles, he and his companion “came in time for another strawberry repast and a rich one it was. We had a new dish, ‘Strawberry Short Cake,’ very fine indeed.” And before leaving Niles the next morning, he partook of one last “strawberry breakfast.” Raisins, dried figs, prunes, currants, and citron were listed in grocery store ads and could be purchased.