What We Wore: Unpacking a Trunk

| Written by | Jeanine Head Miller |

|---|---|

| Published | 10/8/2021 |

What We Wore: Unpacking a Trunk

| Written by | Jeanine Head Miller |

|---|---|

| Published | 10/8/2021 |

Our current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation features clothing from generations of one family. / THF188474

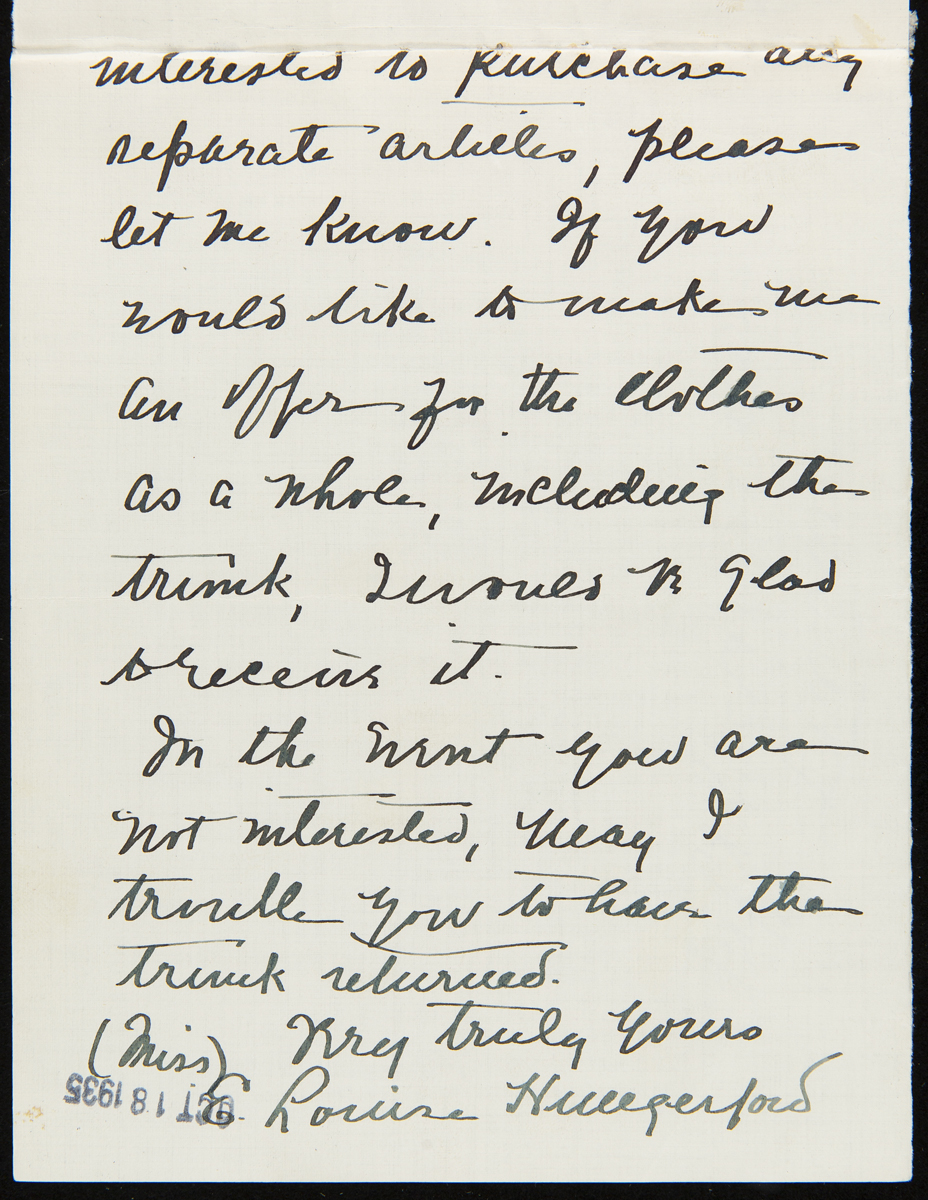

In 1935, 59-year-old Louise Hungerford sent a trunk full of clothing to Henry Ford—clothing that had belonged to her mother’s family, the Mitchells, who had lived in the village of Port Washington, New York, for six generations.

Letter from Louise Hungerford to Henry Ford, September 9, 1935. / THF624791 and THF624793

Ford had opened his museum to the public only two years before. Louise Hungerford was one of the hundreds of people who sent letters to Henry Ford at this time offering to give or sell him objects for his museum. The clothing she sent remains among the oldest in The Henry Ford’s collection.

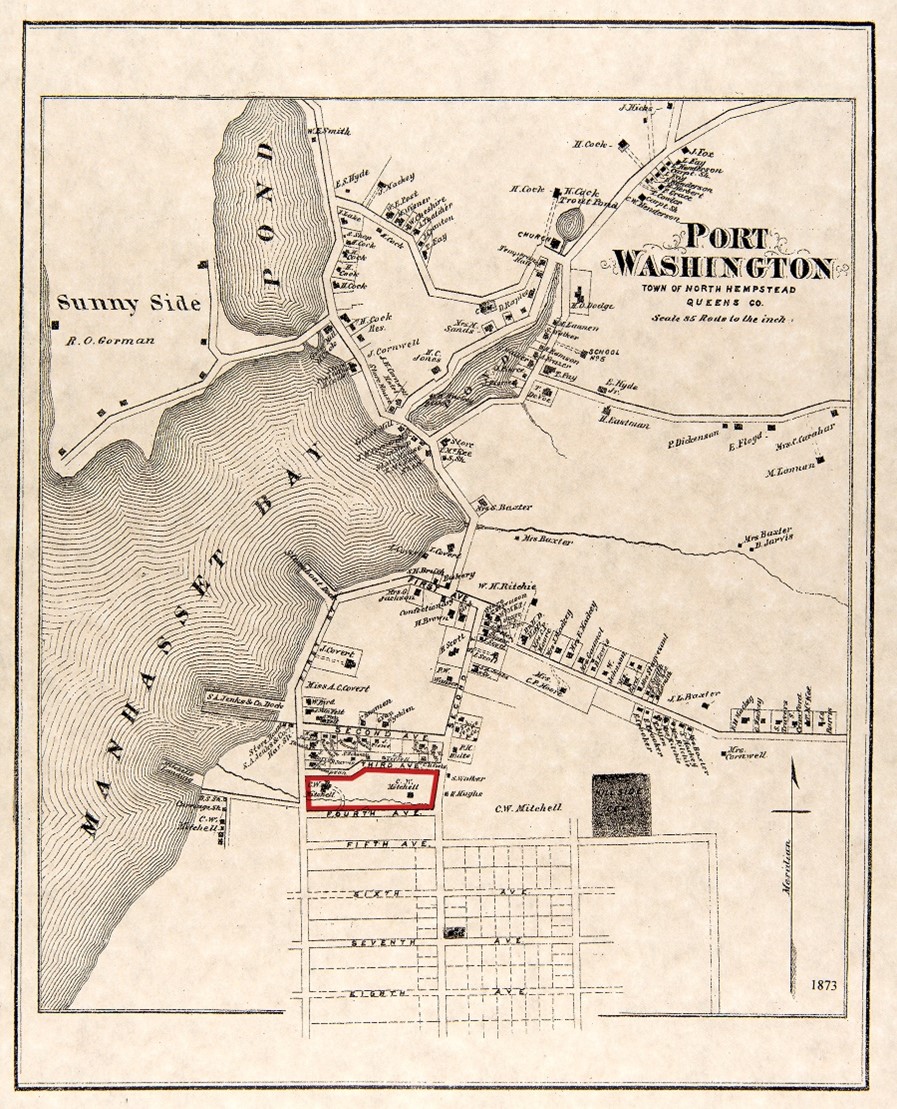

Map of Port Washington in 1873—the Mitchell home is highlighted in red. / (Not from the collections of The Henry Ford.)

The Mitchell Family and Port Washington

Since the 1690s, the Mitchells had been respected members of the Long Island community of Port Washington as it evolved from farming to shellfishing and construction sand and gravel. In the early 1800s, Port Washington (then called Cow Neck) provided garden produce for New York City residents and hay for their horses—all shipped to the city by packet ships. By the mid-1800s, oystering was profitable in the area. After the Civil War, the sand and gravel industry took hold, providing construction materials for the growing city of New York.

By the early 1900s, the village had become a summer resort and home for the wealthy. The Long Island Railroad reached Port Washington in 1898, providing convenient transportation to the area from New York City. The city’s Knickerbocker Yacht Club moved to Port Washington in 1907. By the mid-1930s—when Louise Hungerford sent Henry Ford the letter and trunk full of family clothing--Port Washington’s quaint homes and wooded hills had been giving way to prestigious residences and sailboats for over 30 years.

Postcard views of Port Washington sent by tourists to family or friends about 1910. / THF624985 and THF624981

Mitchell family occupations evolved through the years along with Port Washington’s local economy: farmer, ship’s captain, stagecoach operator, land developer, highway commissioner, librarian.

Preserving the Past

The Mitchell family had changed with the times—yet hung onto vestiges of its past. Family clothing had been stored for over a century, first in Manhasset Hall, the house that had been home to the Mitchells since the late 1760s. Generations of the extended Mitchell family were born there, grew up there, married there, raised families there, and died there.

By the early 1900s, the Mitchell family home—added onto over the years before being sold out of the family—offered accommodations to tourists. The house was later torn down to make way for a housing development. / THF624821

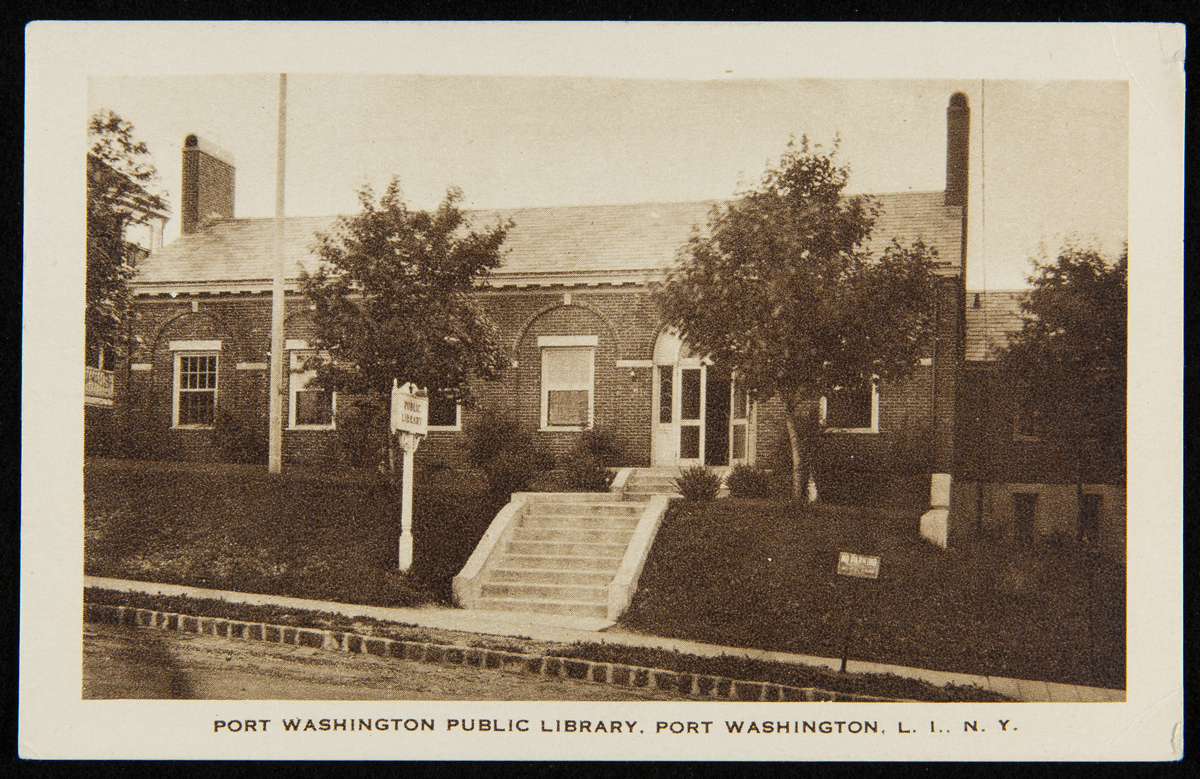

When the Mitchell home was sold in 1887, the trunk full of clothing remained in the family. By the early 1900s, it was probably kept by Louise Hungerford’s aunt, Wilhelmina, and then by Louise’s mother, Mary. Wilhelmina had remained in Port Washington, helping establish the town’s first library and serving as its first librarian.

Port Washington Public Library, where Wilhelmina Mitchell served as the first librarian. / THF624979

Wilhelmina’s sister, Mary Hungerford, lived most of her adult life in Watertown, New York, after her marriage to produce dealer Egbert Hungerford. But, sometime before 1930, Mary—now a widow—returned to her hometown of Port Washington, along with her daughter, Louise. Wilhelmina Mitchell passed away in 1927; Mary Mitchell Hungerford died in 1933. Fewer Mitchell family members remained in Port Washington to cherish these tucked-away pieces of the family’s past. So Louise Hungerford wrote her letter, offering the trunk and its contents to Henry Ford for his museum.

Looking Inside

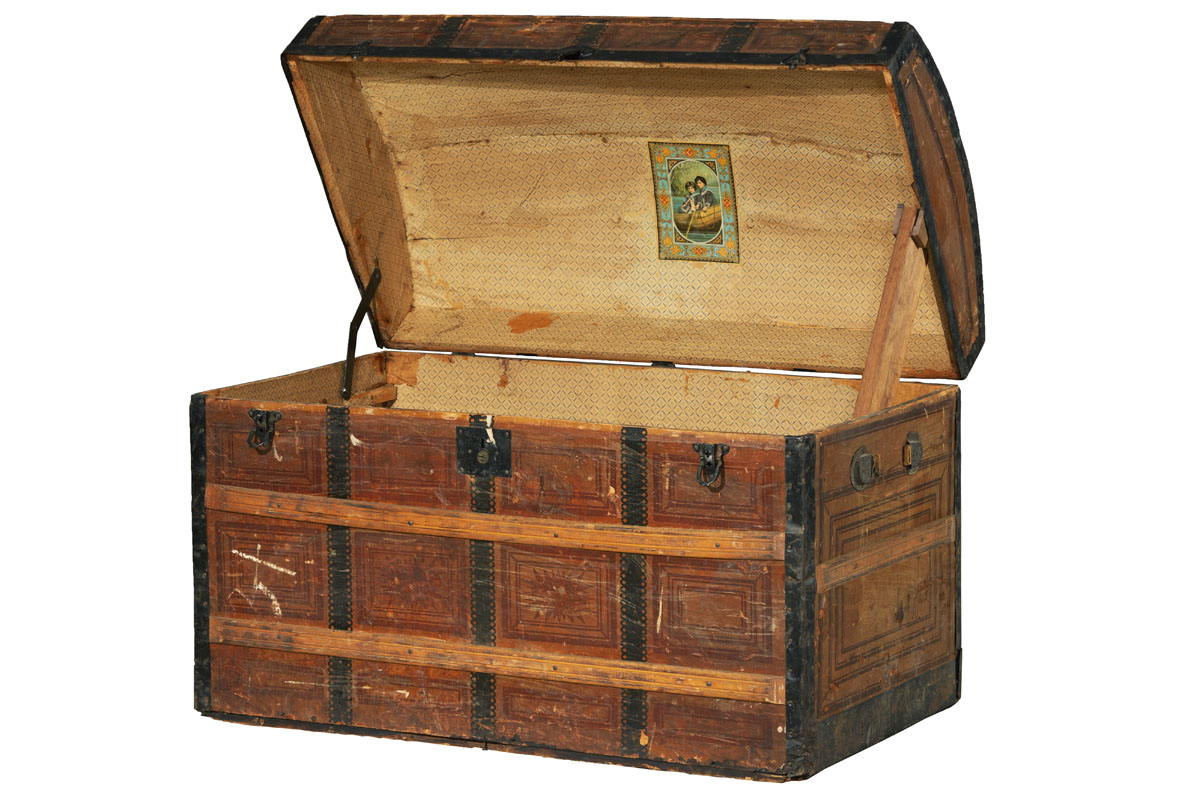

Trunk, 1860-1880. / THF188046

What clothing was in the Mitchell family trunk? Once-fashionable apparel. Garments outgrown. Clothing saved for sentimental reasons—perhaps worn on a special occasion or kept in someone’s memory. Everything was handsewn; much was probably homemade.

Louise Hungerford—if she knew—didn’t provide the names of the family members who had once worn these items, and Henry Ford’s assistants didn’t think to ask. For a few garments, though, we made some guesses based on recent research. For many, the mystery remains.

Women’s Slippers, about 1830. / THF156005

Flat-soled slippers were the most common shoe type worn by women during the first part of the 1800s. The delicate pair above might have been donned for a special occasion. Footwear did not yet come in rights and lefts—the soles were straight.

Child’s Dress, 1810-1825. / THF28528

The high-waisted style and pastel silk fabric of the child’s dress depicted above mirror women’s fashions of the 1810s. This dress was probably worn with pantalettes (long underwear with a lace-trimmed hem) by a little girl—though a boy could have worn it as well. Infants and toddlers of both genders wore dresses at this time. The tucks could be let down as the child grew.

Woman’s Gaiters, 1830-1860. / THF31093

Gaiters—low boots with fabric uppers and leather toes and heels—were very popular as boots became the footwear of choice for walking. To give the appearance of daintiness, shoes were made on narrow lasts, a foot-shaped form. By the late 1850s, boots made entirely of leather were the most popular.

Dress, 1780-1795. / THF29521

By the late 1700s, women’s fashions were less full and less formal than earlier. The side seams of this dress are split—allowing entry into a pair of separate pockets that would be tied around the waist. The dress, lined with a different fabric, appears to be reversible. The dress above was possibly worn by Rebecca Hewlett Mitchell, who died in 1790—or by her sister Jane Hewlett, who became the second wife of Rebecca’s husband, John Mitchell, Jr.

Pockets, 1790-1810. / THF30851

In the 1700s and early 1800s, women’s gowns didn’t have pockets stitched in. Instead, women wore separate pockets that tied around their waist. A woman put her hand through a slit in her skirt to pull out what she needed. This pocket has the initials JhM cross-stitched on the back. They were possibly owned by John Mitchell, Jr.’s second wife, Jane Hewlett Mitchell (born 1749), or by his unmarried daughter, Jane H. Mitchell (born 1785).

Boy’s Eton Suit, 1820-1830. / THF28536

During the early 1800s, boys wore Eton suits—short jackets with long, straight trousers—for school or special occasions. The trousers buttoned to a shirt or suspenders under the short jacket. This one, made of silk, was a more expensive version, possibly worn by Charles W. Mitchell, who was born in 1816.

Sleeve Puffs, about 1830. / THF188039

The enormous, exaggerated sleeves of 1830s women’s fashion needed something to hold them up. Sleeve plumpers did the trick, often in the form of down-filled pads like these that would tie on at the shoulder under the dress.

Corset, 1830-1840. / THF30853

A corset was a supportive garment worn under a woman’s clothing. A busk—a flat piece of wood, metal, or animal bone—slid into the fabric pocket in front to keep the corset straight, while also ensuring an upright posture and a flatter stomach.

Quilted Petticoat, 1760-1780. / THF30943

In the mid-to-late 1700s, women’s gowns had an open front or were looped up to reveal the petticoat underneath. Fashionable quilted petticoats usually had decorative stitching along the hemline. Women might quilt their own petticoats or buy one made in England—American merchants imported thousands during this time.

Man’s Trousers, 1820-1850. / THF30007

These trousers appear to have been worn on an everyday basis for work. Both knees, having seen a lot of wear, have careful repairs.

Woman’s House Slippers, 1840-1855. / THF156001

The quilted fabric on these house slippers made them warmer—quite welcome during cold New York winters in a house heated only by fireplaces or cast-iron stoves.

Calash Bonnet, 1830-1839. / THF188043

Collapsible calash bonnets were named after the folding tops of horse-drawn carriages. These bonnets had been popular during the late 1700s with a balloon-shaped hood that protected the elaborate hairstyles then in fashion. Calash bonnets returned in the 1820s and 1830s, this time following current fashion—a small crown at the back of the head and an open brim. The ruffle at the back shaded the neck.

| When Henry Ford was collecting during the mid-1900s, many of the objects were gathered from New England or the Midwest—often from people of similar backgrounds to his. We are looking to make our clothing collection and the stories it tells more inclusive and diverse. Do you have clothing you would like us to consider for The Henry Ford’s collection? Please contact us. |

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Joan DeMeo Lager of the Cow Neck Peninsula Historical Society, Phyllis Sternemann, church historian at Christ Church Manhasset, and Gil Gallagher, curatorial volunteer at The Henry Ford, for meticulous research that revealed the story of generations of Port Washington Mitchells. Thanks also to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Series | |

Themes |