Monthly Archives: January 2025

Green Museum Work at The Henry Ford

The Henry Ford identified “Cultivating Environmental Responsibility” as one of its strategic goals in anticipation of its 100th anniversary in 2029. A few staff began assessing factors relevant to this goal in August 2019. The Henry Ford’s Green Team (previously the Environmental Focus Group) emerged out of this work and formally organized in May 2021 with responsibilities to benchmark and manage THF’s energy and water use and to reduce waste by recycling and composting. This work aligns with a call to action put forth in Sarah S. Brophy and Elizabeth Wylie’s The Green Museum: A Primer on Environmental Practice, namely, that going green “is becoming mainstream because of its importance, not its fashion” (pg 2).

You could argue that The Henry Ford has pursued green museum work since its beginning in 1929. Certainly, historical precedence lays a solid foundation for current initiatives. Three examples indicate how preservation, reuse, and local sourcing factored prominently in The Henry Ford’s history.

First, historic preservation is a green action. Committing to preservation and adaptive reuse rather than demolition reduces financial costs and energy expenditures.

Rebuilding the Clinton Inn in Greenfield Village, April 1929 / THF149382

Second, reusing landscape features supports actions that reduce environmental degradation. Namely a pond created by laborers excavating clay for use in Anthony Wagner’s brickyard starting in the 1860s became a rainwater holding tank for the museum. Design masked the multi-part infrastructure that re-purposed runoff from museum roofs for use in landscape irrigation.

Pond adjacent to Henry Ford & Son’s tractor plant, October 22, 1918, and north of The Henry Ford’s staff parking area today, remains central to The Henry Ford’s rainwater management system / THF116967

Museum plans drafted in 1928 incorporated pumphouses in two courtyards that pushed rain runoff through a drainage system and into the pond. Facilities managers take this history of environmental change into account when undertaking pond and pumping infrastructure maintenance.

Drawing of the Virginia Court with pumphouse replicating a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

Third, Henry Ford confirmed the importance of locally sourced materials when he constructed the chemical laboratory at the entrance to Greenfield Village. More than a dozen chemists worked in this structure, seeking domestic products for industrial use. By December 1931, soybeans became the focus of their research, and a new agricultural commodity took hold in southwestern Michigan. Ford joined others in Illinois, North Carolina, and beyond, exploring the potential of soybeans to meet local industrial demand for alternative oils for paint and alternative proteins for foods. Today we know that locally sourced products reduce carbon emissions by reducing transportation from the point of production to processing and consumption locations.

Chemical laboratory in Greenfield Village with Lovett Hall, The Edison Institute, visible in the background, 1930. This image predates Henry Ford instructing the chemists to focus on soybeans / THF236433

These historic approaches (among others) laid a firm foundation for Green Team actions over the past five years (2019 to 2024). Staff prioritized benchmarking, recycling, and composting as important steps toward cultivating environmental responsibility. Efforts aligned with national initiatives such as the Culture Over Carbon project, funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. More than 130 cultural institutions across the United States, including The Henry Ford, shared energy-use data that identified trends for the field. This supported a larger goal, to establish a cultural institution benchmark for Energy Star ratings.

Green Team members also engaged with Detroit’s 2030 District chapter through which they met with other museum and culture partners within and beyond the area. The national network of 2030 Districts, made up of businesses, cultural institutions, and municipal governments, all in efforts to pursue new models for urban sustainability and economic vitality. Ongoing conversations help put institutional work into context, including a signature accomplishment at The Henry Ford in 2024, namely, the installation and operation of the second biodigester in the Detroit area.

The Henry Ford staff, Amber Stankoff, producer (left) with Brian Egen, executive producer and head of studio productions (center), filming Alec Jerome, senior director of facilities management and security, discussing the biodigester installed at Stand 44, the new restaurant in Greenfield Village, June 26, 2024. Photograph by Debra A. Reid.

These actions are steps on the longer path toward cultivating environmental responsibility. Extending information more broadly to THF staff and guests makes clear how each of us will contribute to realizing this ambitious goal. Doing so will ensure a more stable environment for staff and guests in perpetuity.

Debra A. Reid is curator of agriculture and the environment at The Henry Ford and has been a member of the Green Team since its formation. She serves on the Climate & Sustainability Community of the American Association for State and Local History and is the secretary of the International Council of Museums' international committee, SUSTAIN (Museums and Sustainable Development).

Adventurous Dining, Audacious Art

In 1963, the artist, activist, and educator Corita Kent worked in partnership with the American seasoning brand Spice Islands Company to create this publication, “International Dining with Spice Islands.” Originally sold as a mail-in incentive, it contains culinary histories, recipes, and suggested menus that are aimed at demystifying global cuisine for American home chefs. The folded paper presentation sleeve contains ten booklets focused on the cuisine of “nine of the world’s most savory kitchens”: France, India, Japan, Germany, Italy, Spain, Greece, Israel, and Sweden. Unfolding the unassuming gold and cream-colored outer sleeve, a kaleidoscope of movement and color emerges. Each of the ten booklets inside is wrapped in a colorful reproduction of a Corita Kent serigraph—overlaid with a handwritten proverb relating to the cuisine featured inside.

Presentation sleeve for the “International Dining with Spice Islands” recipe portfolio / THF720260

Spanish recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “Reading and eating should both be done slowly.” / THF720271

At age 18, Corita joined the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles. From 1947-1968 she taught art at Immaculate Heart College, where she eventually became chair of the art department. This liberal arts school had a reputation for its progressive curriculum, which coincided with the shifts and reforms of Vatican II Catholicism in the 1960s. Corita was a vibrant individual whose belief in the importance of community, intentional presence in the world, and social protest through art are reflected in her teaching philosophy and own creative output. She was extremely active as an artist while teaching at IHC, exhibiting widely and receiving international attention for her bold pop art styled serigraphs (or screen prints).

Corita often referenced the visual language of food logos in her prints—famously, pairing Wonder Bread and Sunkist logo designs with fragments of scripture, song lyrics, poems, and quotes from public figures. Regarding her work for the “International Dining” publication, the Corita Art Center states, “These succinct and charming proverbs echo Corita’s use of food advertising language to playfully connote spiritual messages within her artwork.” The publication was popular enough that they were reprinted in 1967, which is the version recently acquired by The Henry Ford.

Introductory booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with a quote by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin / THF720261

The cover of the introductory booklet references a quote from Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, an 18th-century French lawyer and author: “The joys of the table belong equally to all ages, conditions, countries and times; they mix with all other pleasures, and remain the last to console us for their loss.” As the author of “The Physiology of Taste: Or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy,” Brillat-Savarin is considered one of the first essayists of the gastronomy genre. He also famously wrote “tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are”—the origin point for the common adage, “you are what you eat.”

The first booklet also contains a brief history of fine dining and provides instructions and etiquette for how to form an “international dining club” with adventurous diners. These clubs “…need not be a stuffy aggregation of posturing food snobs” but should be “…a congenial group of acquaintances who need hold nothing more in common that a singular interest in food.”

French recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “To invite anyone to dine implies that we charge ourselves with his happiness all the time he is under our roof.” / THF720264

Today, Spice Islands branded herbs are commonly sold in American grocery stores. The company was founded in 1941 and currently operates production facilities in Ankeny, Iowa—home to the largest American spice brands in the US. Geographically speaking, the “Spice Islands” themselves refer to the Malaku or the Moluccas—a group of Eastern Indonesian islands that became a powerhouse of spice trade with the arrival of European and Portuguese ships in the 16th century. The main spices exported from the Spice Islands were “warming spices”: nutmeg, cloves, mace, and peppercorns.

Beyond Corita’s contributions to the “International Dining” project, James R. Stitt is credited as the main art director and designer. Following his service in the US Navy and Marines, Stitt worked as a technical illustrator for Boeing before moving into the corporate advertising field in San Francisco. In the early 1960s, while working at the firm Dancer Fitzgerald Sample, he was assigned the Spice Islands account. Stitt recalled meeting Corita Kent at the ArtCenter School in Los Angeles while he was a student, and as a fan of her work, contacted her to commission illustrations for covers of the “International Dining” recipe booklets. Despite working as an illustrator in the years when digital design was on the rise, Stitt was staunchly anti-computer throughout his career. His iconic labels for the Anchor Brewing Company were entirely drawn by hand; they included 44 years of Christmas Ale labels starting in 1975 until his retirement in 2019.

Greek recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “He who is too lazy to knead the bread must sift the flour for five days.” / THF720266

Country by country, the booklets contained within the “International Dining with Spice Islands” portfolio explain indigenous regional cuisines, shifting foodways, hospitality expectations, seasonal menus, the impacts of religious belief on food preparation and consumption, and cuisine balanced with local agricultural abundance (or scarcity). Also included are sources for seasonings not readily available in typical US retail grocery stores in the 1960s. (Michigan locations include J.L. Hudson Company in Detroit.) Chefs are urged to take seasoning seriously and to broaden their palates: “If you are not familiar with a particular herb, spice, or seasoning called for in a recipe, do not omit it. […] Broadening one’s seasoning scope is an exciting adventure in itself.”

Spanish recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “Food must feast the eyes as well as the stomach.” / THF720270

Italian recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “Thou shouldst eat to live not live to eat.” / THF720269

Indian recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “If you would be a king you must eat like a king.” / THF720267

German recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “He who doesn’t love wine women and song remains a fool his whole life long.” / THF720265

Israeli recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “When you spread the table contentions will cease.” / THF720268

Swedish recipe booklet with art by Corita Kent from “International Dining with Spice Islands” with the proverb “You take what you have.” / THF720272

Kristen Gallerneaux is curator of communications & information technology, editor-in-chief of digital curation. .

Conservation Spotlight: 19th Century Passenger Cars

If you had a chance to visit the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in 2024, you may have seen a few members of our conservation team working by the legendary Allegheny, on the three cars attached to the replica DeWitt Clinton locomotive. For a few months, we chatted with visitors about conservation and our preservation efforts on these artifacts. Let's look at the full process now that conservation work is complete!

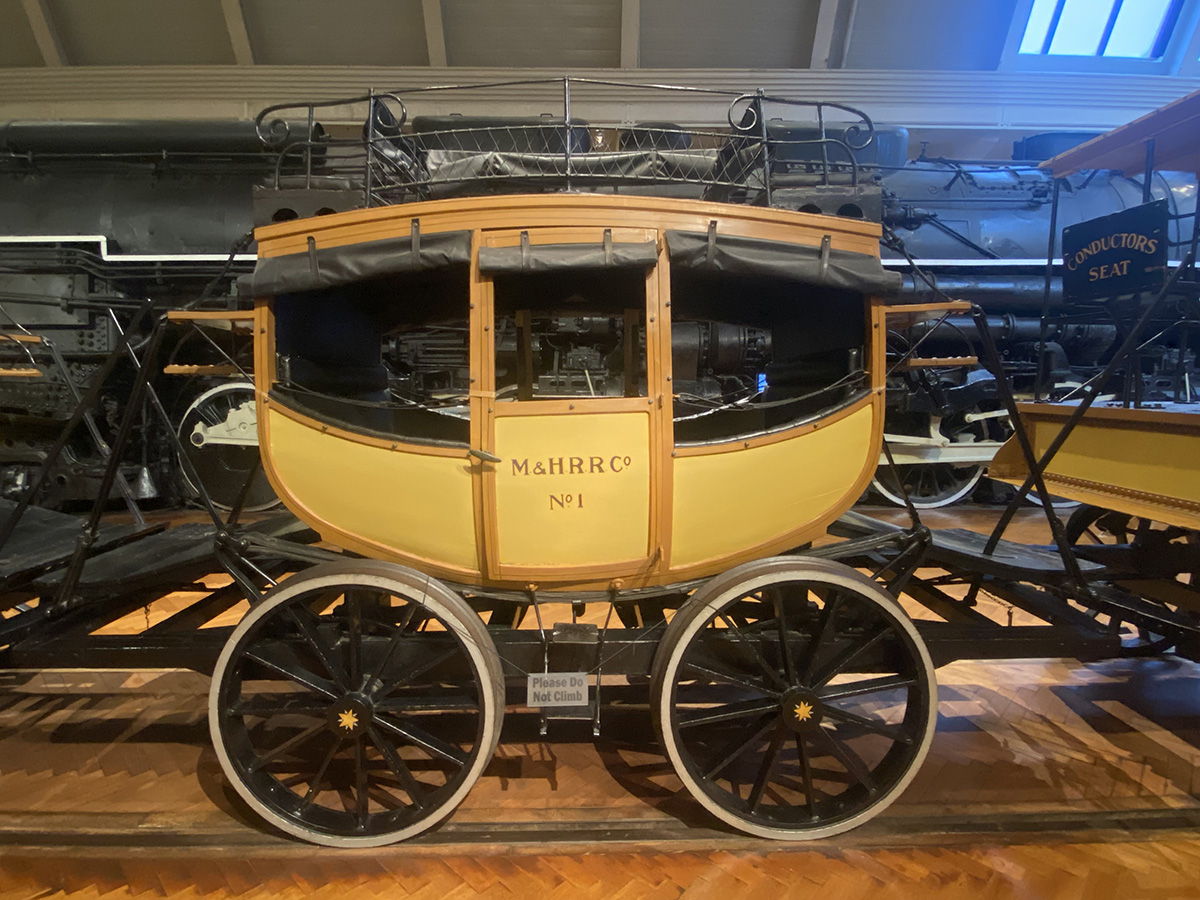

First car

Made in 1893 by the New York Central Railroad for the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago and various promotional events, the locomotive and passenger cars are replicas of the 1831 DeWitt Clinton. Henry Ford acquired the replica locomotive and carriages in the 1930s, which are now displayed on railroad tracks as if ready for their next journey.

Second car

Both their days of use and time on display have contributed to the wear and tear on the locomotive and its cars. Our fabulous clean team documents changes to the artifacts to report to Conservation. For the replica DeWitt Clinton passenger cars, the clean team noticed broken leather straps, lost paint, torn leather cushions, and a missing seat cushion.

Third car

This year, we made it a priority to give the cars conservation attention. Since these are large artifacts, instead of moving them to the conservation lab, cleaning and repairs were done on the museum floor.

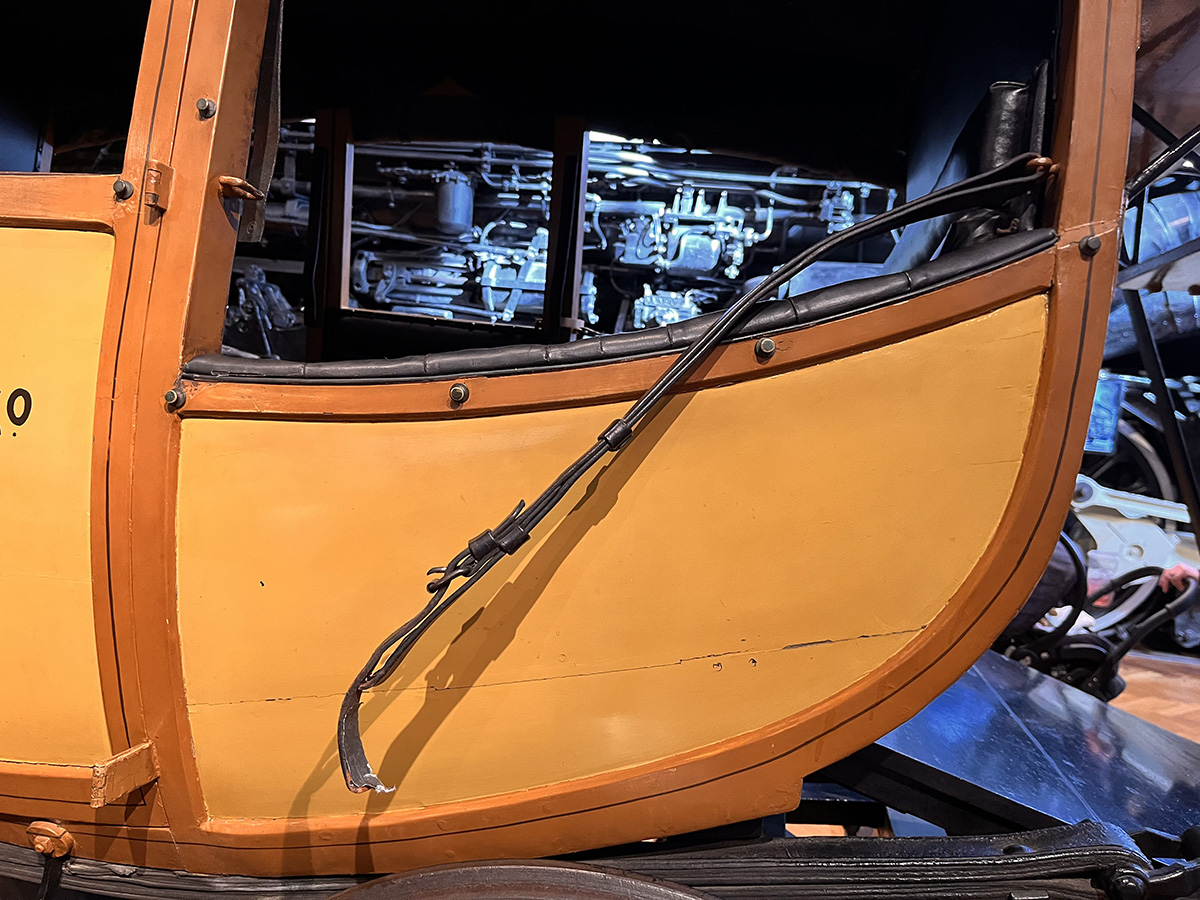

Broken leather strap on one of the cars

First, broken and brittle leather belt straps in the windows of each car were removed for replication by a local leather worker. The straps were measured and fabricated to match the full length and appearance of the original straps in completed form. The original metal buckles were saved to fit the straps back to the windows.

Surface grime on car exteriors visible around the lettering

The exteriors of the cars were cleaned to remove surface grime and expose the richness of the bright mustard and reddish-brown paints. At this stage, it allows us to see other issues that we may have missed upon the first examination. Not only were paint losses visible on the surface, but losses in the wood frame were found on the rear car.

Filled losses with gesso to create even layer before painting

The unstable paint was carefully adhered back in place and large losses filled with gesso or wood putty before painting to match the rest of the car.

Wood putty fill in center

Pinstripes and lettering on the car doors were also touched up. If there was structural damage, strong wood putty was used, otherwise the gesso was used for shallow fills.

Large paint loss on side panel

Otherwise, after concocting just the right proportions of pigments, wax fills were chosen to provide good color match for shallow surface damages. Smaller losses were filled with the pigmented waxes applied vertically using a warm tacking iron, mindful not to drip wax everywhere!

Torn leather on cushion

Tufted seat cushions with torn leather were removed from the cars and taken to the conservation lab. The tears were mended with adhesive film activated by heat. Any gaps in the lost leather were filled with pigmented wax. The buttons were re-secured where necessary with stronger twine.

Cushion after stabilization

The missing seat cushion on one of the cars was recreated by a local car upholsterer. See if you can spot the new one! We make sure new materials added to artifacts are documented in condition and treatment reports for future conservators to know what is original versus a replication.

Each car's leather armrests had been previously repaired with tape strips to cover lost material or insecure leather. Over time the tape started to peel away, drawing more attention to these damaged areas.

Adding leather tape patches to losses on armrests

We removed the old tape and adhesive before attaching leather tape patches cut for specific loss areas instead of covering the entire armrest.

Applying wax to small losses on armrests

As seen with the seat cushions, pigmented wax was applied to the gaps between the original leather and the new patches to create as seamless a finish as possible while securing the edges of the tape to the armrests.

3D-printed tacks ready for attachment

Final additions involved replicating lost tacks around the window shades and interior leather panels of each car. Example tacks were scanned to create digital models for 3D printing. Close to 100 printed tack models were then painted to look like corroded metal or leather covers for the tack heads and secured with adhesive. Once the last tack was attached, our rejuvenating treatment was complete!

View of all three cars from the Allegheny

We heard many visitors standing in awe of the replica DeWitt Clinton and what must have been quite the experience of riding these passenger cars long ago. This behind-the-scenes look at what it takes to preserve some of the larger items in our collection gives a taste of the detailed work our conservation team does every day to continue the legacy of these historical artifacts.

Marlene Gray is a senior conservator at The Henry Ford. Huge thanks to conservation specialists Fatima Sow, Julia Fahling, Scott Powers, and senior conservator Cuong Ngyuen for their work on the passenger cars.

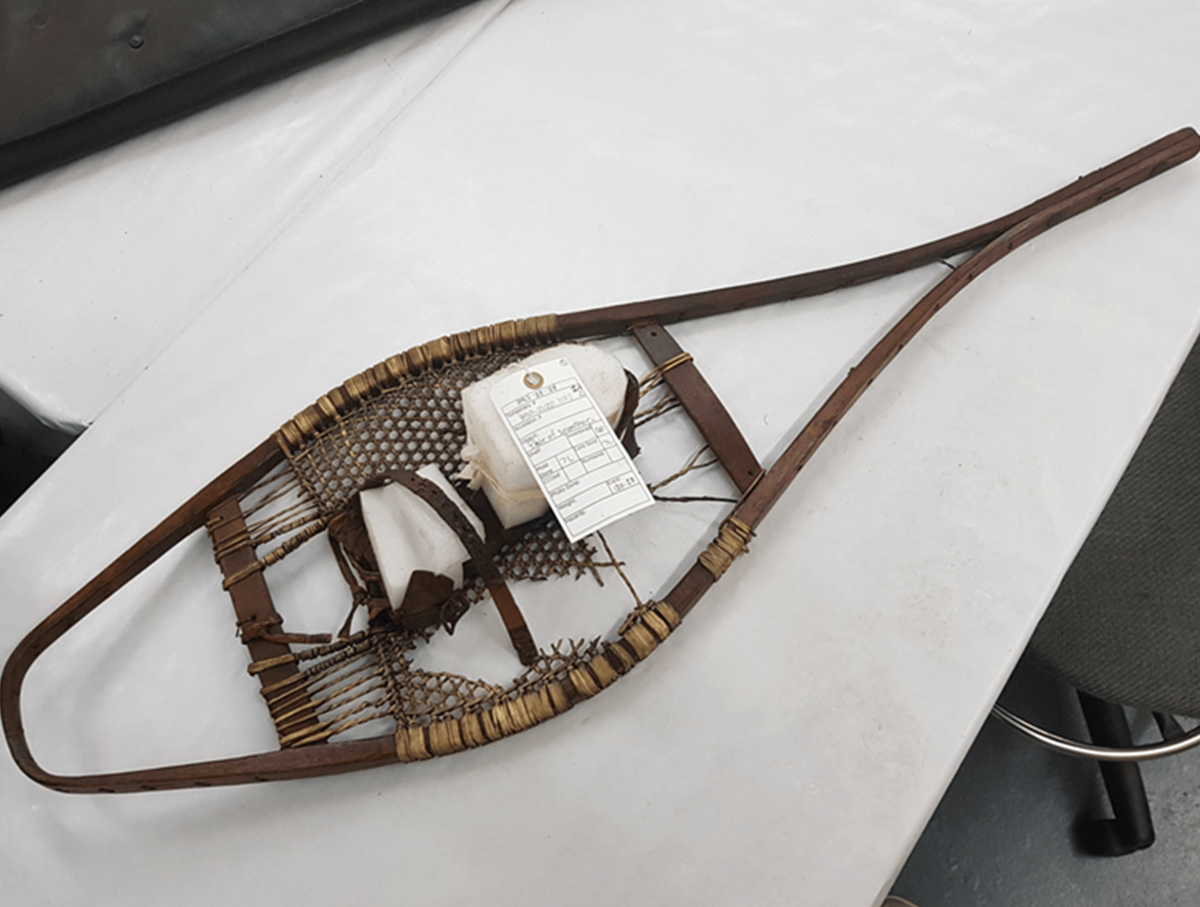

Snowshoes: 2024 IMLS Feature

As we come to the end of our 2022-2024 IMLS (Institute of Museum and Library Services) grant project, the Conservation staff are showcasing standout objects recently treated. During the two-year project we have conserved and relocated 2,106 objects, and created fully digital catalog records for 815 of these. The following blog highlights the snowshoes that made their way through this grant, now made accessible to the public via The Henry Ford’s Digital Collections.

Snowshoes have a long history in North America. Indigenous peoples invented the form using thin strips of collagenous material (sinew or treated hide) and bent wood. The woven strips created a netting used for walking on snow. In fact, using snowshoes helped Indigenous peoples in snowy areas thrive during wintertime. The shoes facilitated trade, hunting, trapping, and self-defense. You can read more about the advantages of Indigenous snowshoe knowledge in Thomas M. Wickman’s book, Snowshoe Country: An Environmental and Cultural History of Winter in the Early American Northeast (2018).

Wickman focuses on the Wabanaki, including Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot peoples, in northern New England. The Wabanaki held advantage in the area during the 1600s, but by the early 1700s, British colonizers co-opted Indigenous tactics, including snowshoes, and launched winter offensives with the goal of eliminating their Indigenous opponents. Snowshoes then became a tool that British colonizers used for daily winter transport.

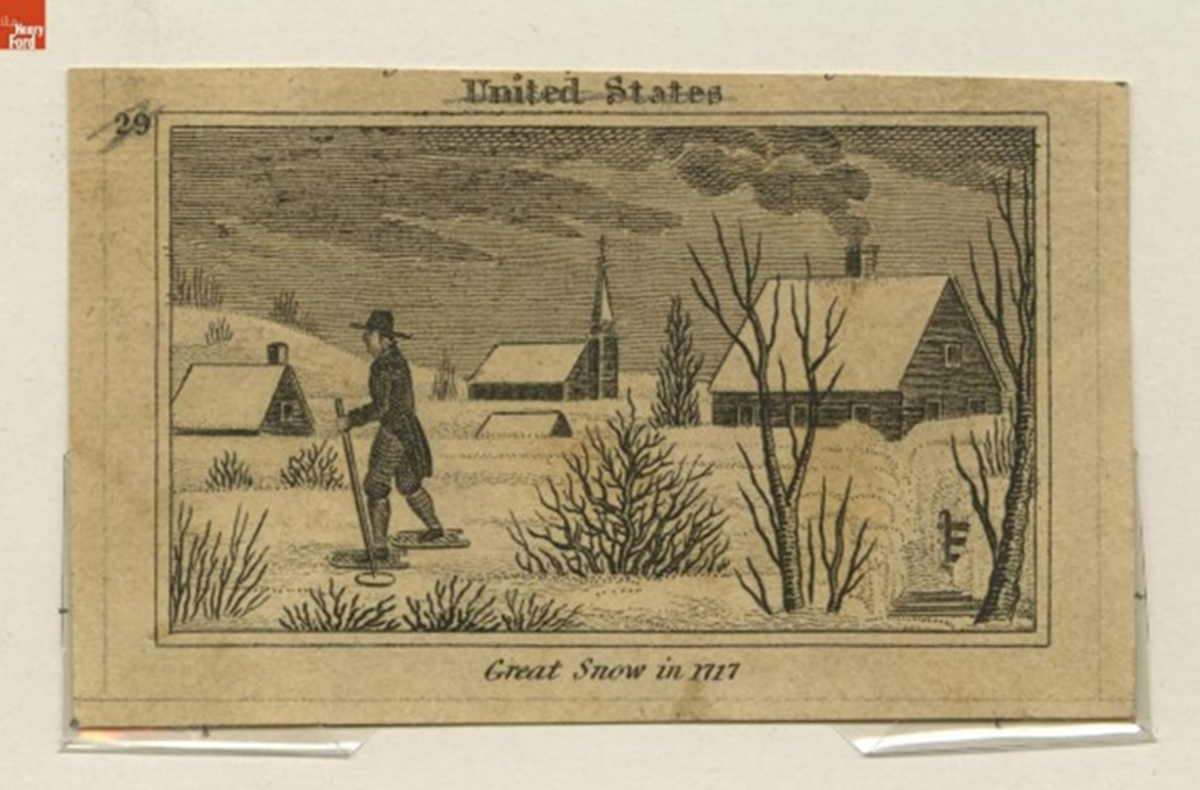

Copperplate engraving made around 1820, "Great Snow in 1717" / THF118620

A description of the “Great Snow Storm” of 1717, included in Historical Scenes in the United States (1827), described the snow as being so deep that “people stepped out of their chamber-windows on snow shoes.” The author, John W. Barber, mentions consequences of the 1717 snow, a “terrible tempest” that trapped New Englanders in upward of 15 feet of snow accumulated over several storms in late February and early March. The rather bucolic illustration does not convey the tragedy of the weather event. The 1891 book Historic Storms of New England does a better job. Author Sidney Perley puts the storm into context in his chapter, “The Winter of 1716-1717,” including the loss of livestock and humans. He also provides detail about those colonists who donned snowshoes, including mail carriers and residents who relied on the shoes to tend to livestock or assist neighbors, and sometimes to visit sweethearts.

Native American Basket Market, Ojibwa Tribe, Mackinac Island, Michigan, September 1904 / THF118996

Indigenous knowledge remained essential to snowshoe construction. A photograph shows Ojibwa people selling baskets, and in the background, a pair of snowshoes leaning against a tree. The snowshoes treated during the IMLS grant project lack the decorative tufts of either dyed moose hair or wool visible on the Ojibwa snowshoes, but the intact webbing, carefully conserved, still indicates the craftsmanship evident in each shoe.

Some of the snowshoes in The Henry Ford’s collections still have their leather ankle loops and toe thongs intact. These details secured the toe to the shoe, leaving the heel free to lift the shoe and step forward with each stride.

The following images show the work of conservation, and the photography that was used to document our process. We are pleased to be able to share these remarkable artifacts via THF’s Digital Collections.

One shoe of a pair of snowshoes needed stabilization before proper handling. A section of the wood frame was missing, leaving sharp pieces of wood sticking out. The dowels keeping the tail together had split, causing more tension on the weakened rawhide webbing. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The tail was stabilized with painted wooden dowels inserted between the gaps that were secured with wood glue. The large loss to the wood frame was filled with a wood putty that was levelled, scored with a dental pick to create the wood grain, and painted to match the rest of the wood. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The rawhide was then cleaned with a mild detergent and distilled water with a stiff brush to remove as much dirt as possible. The rawhide webbing is rather sturdy, even where it had detached from the wooden frame, and was not in need of reattachment at this time. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

Another pair of snowshoes in a different shape from the previous pair has leather shoe holders attached to the mesh component made of rawhide. One-fourth of the mesh is missing, while the rest of the mesh was stained by dirt and dust. The overall surface of the leather was fragile, cracked, missing, and broken in some areas. A leather strap to hold the toes was split and separated from the object. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The leather was consolidated with Jade R adhesive and Japanese tissue attached to the reverse side of broken leather areas after cleaning with distilled water. The split leather strap was also reattached in the original position by the same restoration method. The restored areas by Japanese tissue were painted to match the rest of the leather. The rawhide was cleaned with the same method as described with the previous snowshoes. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The leather shoe holder is held in place with a foam support to keep the shape and avoid further physical damage. Oil-based gel stain mixed with nutmeg and antique walnut color was applied on the wood surface of the object to match the rest of the color of the wood. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

Thanks to the work of the IMLS team, the care and conservation of these organic artifacts is complete. In the photo studio, the snowshoes presented even more complexities.

They proved to be one of the trickiest (and most delicate) objects photographed throughout the IMLS grant project. Senior photographer and studio manager, Jillian Ferraiuolo, outlines below how the snowshoes needed to be handled carefully to be properly photographed.

Snowshoes set up for photography / Image by Jillian Ferraiuolo

Because they are so large, the snowshoes were photographed on the ground, with white boards placed underneath to protect them from the floor. A white background also makes it easier to clean the background during the editing phase and remove anything that’s not a part of the object.

Object 2022.0.22.646 / THF800530

Object 2022.0.22.645 / THF800534

Object 2022.0.22.644 / THF800535

Photographing the snowshoes was one of the final steps towards getting these important objects added to THF’s Digital Collections webpage. Thanks to IMLS funding, these and more artifacts that tell agricultural and environmental histories have become more accessible.

This blog was written by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim), IMLS project conservator; Jillian Ferraiuolo, senior photographer & sudio manager; and Debra A. Reid, curator, agriculture and the environment.

Marlene Gray, senior conservator; Julia Fahling, conservation specialist; Eleanor Glenn, former conservation specialist; Mary Fahey, chief conservator; and volunteers (Eric Bergmann, Maria Gramer, Frances McCans, and Larry McCans) assisted Jee throughout the two-year grant project.