Posts Tagged by rachel yerke osgood

Gone But Not Forgotten: Fisk Iron Coffins

In early 19th-century America, life was changing fast. More Americans were venturing farther from home as the country expanded westward and new innovations in steam and rail transport made travel more accessible. This also meant that more Americans were dying far from home. Society, though, still viewed it as important that a person be laid to rest among their family; to not have this final closure would have been deeply upsetting.

New York stove maker Almond Dunbar Fisk found himself in this very situation when his brother, William, died in Mississippi in 1844. Fisk’s family was unable to have William’s body returned to New York to be buried in the family plot, and the sorrow of the situation propelled Almond to look for solutions for families in similar situations. After applying his own knowledge of creating furnaces and boilers and consulting with experts in organic decomposition, in 1848 Fisk was granted a patent for an airtight cast iron coffin. With his father-in-law, Harvey Raymond, Fisk opened “Fisk and Raymond” in Manhattan and began selling his iron coffins.

Mummiform Iron Coffin, 1854-1858. This small coffin is unused and was possibly kept as a sales sample. / THF370110

Once thought to be only the privilege of the wealthy, more recent evidence and research suggest that iron coffins were relatively popular in the years before embalming became a common practice around the time of the Civil War. This makes sense when you consider how many practical issues the iron coffin addressed, beyond just body transport. Cholera was plaguing the nation, and the airtight seal of Fisk’s coffin design helped assuage fears of spreading the disease (as cholera is one of the incredibly few diseases that can be contagious even after death). Fisk and Raymond also advertised their coffins as a deterrent to grave robbery, although the fear of such acts was perhaps more prevalent than the act itself.

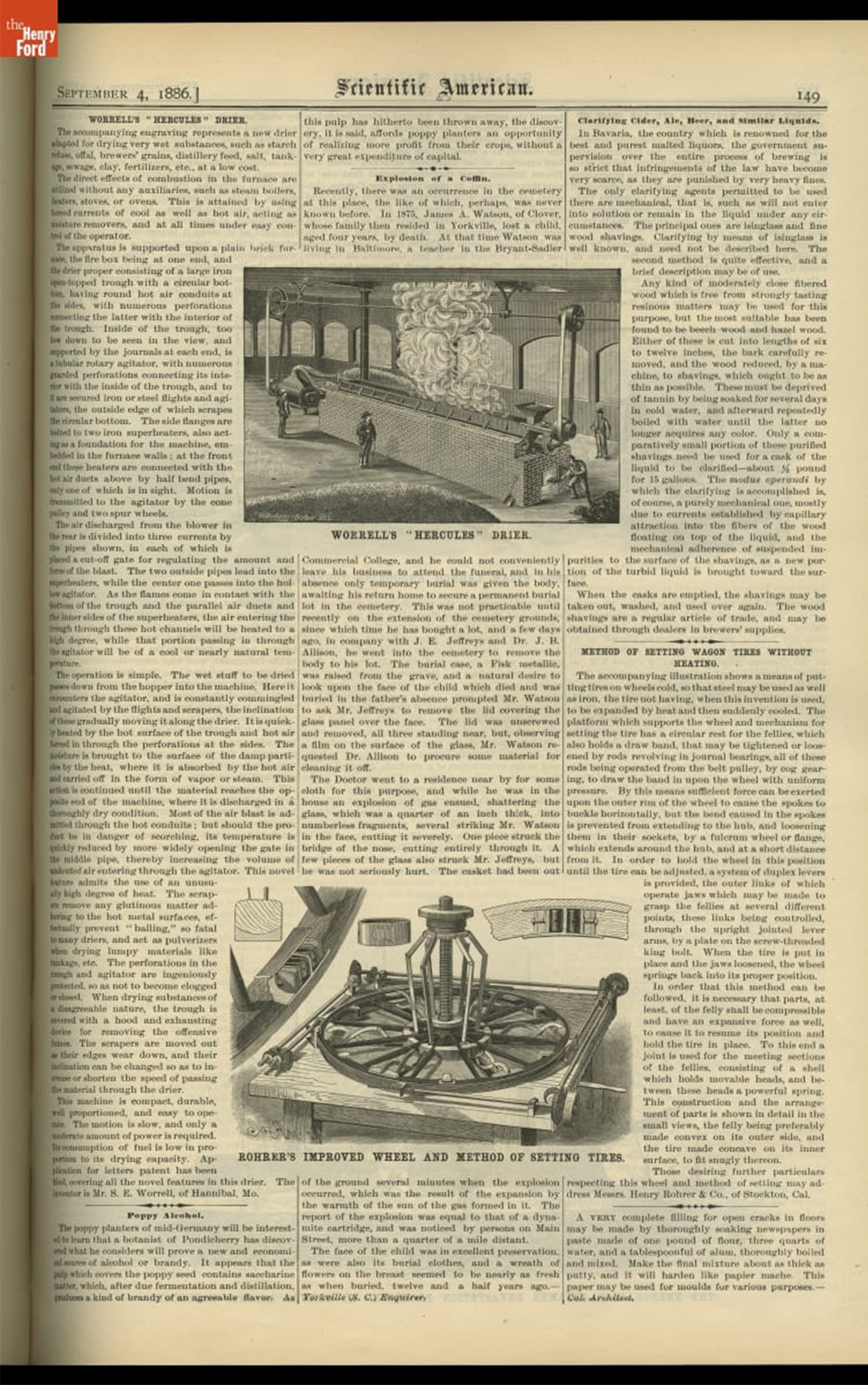

Iron coffins would be used or endorsed by several notable figures, including Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, James Monroe, Dolley Madison, John C. Calhoun, and Zachary Taylor. But they also received a bit of notoriety for another reason: anecdotes relating how they would occasionally “explode.” One such story in the September 4,1886, issue of Scientific American is fairly typical of the reporting of such stories: while waiting for family to return from out of town to arrange for a proper plot, a body was buried in a metal coffin in a temporary grave. When the final resting place was ready, the body and coffin were exhumed, and a family member asked to see their loved one’s face in the little glass window. The metal lid over the face was removed to reveal a glass viewing window, and the face was there—perfectly preserved. While the coffin was left briefly unattended before burial, “an explosion of gas ensued, shattering the glass . . . into numerous fragments . . . The report of the explosion was equal to that of a dynamite cartridge.” While it is in fact true that the buildup of gas inside the coffin could cause the glass to fracture and then break, particularly if there was a change in temperature, the strength of the “explosion” was often overstated for the sake of a more sensational story to tell.

Scientific American, Vol. 55, July-December 1886. The story of a Fisk coffin rupturing is found in the center column, under "Explosion of a Coffin.” / THF705631

While “Fisk coffins” or “Fisk burial cases” would become the shorthand for these iron coffins, Fisk and Raymond was not the only manufacturer. Through a combination of licensing the manufacturing rights, the patent changing hands, and changing company names, iron coffins were produced by companies including: W.C. Davis and Co.; Crane, Barnes and Co.; Crane, Breed and Company; W. M. Raymond and Company; and Metallic Burial Case Company. While production of these metallic coffins would cease around 1889, remaining stock continued to be sold until the start of the 1900s.

This “Fisk coffin,” produced by Crane, Breed and Company., maintains the mummiform shape of the original Fisk patent, but its decorative design is distinct to the manufacturer. The coffin mimics the folds of a burial shroud, and the rose at the foot is a common burial symbol, often used on headstones to convey various meanings. / THF370111

The Henry Ford is lucky enough to have one of these coffins in our collection—joining institutions such as the Memphis Museum of Science and History, Museum of Appalachia, the LSU Rural Life Museum, the Simpson Funeral Museum, and the Smithsonian. It provides a beautiful example of Fisk’s invention, and demonstrates the importance of keeping our loved ones close—even after death. Together with objects like our burial quilt, mourning jewelry, and items related to Dia de Muertos, our death-related collections paint a picture of the myriad ways grief, mourning, and remembrance manifest themselves. Macabre as these items may be to some, we need only dig a little deeper to see that they contain stories of great love and care.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

With gratitude to Scott Warnasch for sharing his detailed research.

Thoughtfully Crafted: Sustainable Products from Liberty Craftworks

At The Henry Ford, we have dedicated teams of craftspeople who create beautiful products in our Pottery, Glass, Weaving, and Print shops, which make up Liberty Craftworks in Greenfield Village. While these artisans use traditional techniques, they also do their fair share of innovation. One of the areas in which we have recently expanded is in our offering of products from Liberty Craftworks that use recyclable material sourced on-site.

Bookmarks made from recycled paper. / Image by The Henry Ford

Bookmarks made from recycled paper. / Image by The Henry Ford

Printmakers will check or proof their work by pulling test prints. Most times the results are positive although sometimes the outcome is unexpected. At this point, many prints could be considered misprints that can’t be used. In the Print Shop, they become the perfect opportunity for recycling and creating unique useful items.

Pin-back buttons created from test prints in the Print Shop. / Image by The Henry Ford

Pin-back buttons created from test prints in the Print Shop. / Image by The Henry Ford

For example, the covers of our pocket-size journals were made with test prints from various posters created to be sold in the gift shops. Test print "Makers" posters were trimmed into distinctive bookmarks. A fitting Edison quote was handset and printed on the bookmark finished with a coordinating silver ribbon. Artisans also use test prints to make pin-back buttons. The print is punched with a circle punch and then pressed with a button-maker into coordinating size button hardware ready for a pin back to be added creating a one-of-a-kind button.

Pint glass created from recycled glass. In the background, you can see the variation that occurs, even when using one color of leftover glass. / Image by The Henry Ford

Pint glass created from recycled glass. In the background, you can see the variation that occurs, even when using one color of leftover glass. / Image by The Henry Ford

The Glass Shop uses recycled glass to create rocks and pint glasses. For each "run,'' or production batch, over 200 pounds of glass is diverted from the landfill. As with of our recycled handmade items, the colors of the glassware can vary depending on what colored glass is available and used.

Artisan creating pottery in the Pottery Shop. Mini bowls made from extra clay and remnant glaze are in the foreground. / Image by The Henry Ford

Artisan creating pottery in the Pottery Shop. Mini bowls made from extra clay and remnant glaze are in the foreground. / Image by The Henry Ford

In the Pottery Shop, mini bowls are made from scraps of clay that are mixed together into a recycled clay blend. They are made from a variety of clay colors that are swirled together in the mixing process. Once the pieces are formed, they’re fired in a kiln to 1,950 °F and then dipped into a glaze. The glazes themselves are mixtures of leftover glazes from various projects. The glazed pieces are then fired again, this time to 2,100 °F. Each finished product is unique, and the fact that they are made from clay and glazes that have been recycled only adds to their beauty and distinctiveness.

Pouches made from Weaving Shop remnants, Clothing Studio scraps, and Pottery Shop buttons. / Image by The Henry Ford

Pouches made from Weaving Shop remnants, Clothing Studio scraps, and Pottery Shop buttons. / Image by The Henry Ford

When the Weaving Shop is lucky enough to have remnants, weavers use them to make colorful pouches. These unique creations also provide the opportunity for cross-collaboration among several teams. The pouch linings are made from remnants from the Clothing Studio, our internal textile department that creates all our historically accurate clothing and programmatic costumes. The buttons are scraps from the Pottery Shop. While the pouches are not always available, when they are, no two pouches are exactly alike.

These sustainable pieces help tell the story not only of historical craft, but of the importance of sustainability. The next time you are in one of our stores or shopping online, keep an eye out for these unique creations, and others from our innovative artisans.

- Mendy Grenz, Weaving Shop Lead

- Chris Hoffman, Glass Shop Lead

- Melinda Mercer, Pottery Shop Lead

- Kathy Torres, Print Shop Lead

Compiled by Zachary Ciborowski-Scarsella, Manager of Retail Marketing & Licensing, and Rachel Yerke-Osgood, Associate Curator

Making the Connection: Phoning on the Go

When telephones were first introduced in the late 1800s, people wanting a phone would subscribe to the local phone company’s services and receive a telephone on lease. Using the telephone at this time meant that both caller and receiver were tethered to their respective locations. But as American life became more bustling and more people found themselves away from home for greater portions of their day, telephone technology adapted.

Pay telephone featuring patents by William Gray, circa 1898 / THF805358

Pay telephone featuring patents by William Gray, circa 1898 / THF805358

In 1889, the first public, coin-operated pay telephone was installed in Hartford, Connecticut, at the Hartford Connecticut Trust Company. The device had been conceived of and patented by William Gray; according to legend, he was inspired by his inability to find a publicly available phone when his wife was ill and needed a doctor. The pay telephone worked by creating slots for different denominations of coins, and different chimes or bells would sound as the money was deposited. Once the right amount had been deposited—the operator could tell by the chimes—the call would be put through. The Gray Telephone Pay Station Company, founded by Gray in 1891, would go on to install pay telephones across the country and refine their designs, creating different models for different needs and locations, from city streets to hotel lobbies. The company would be incredibly successful, even surviving the Great Depression before being bought out by Automatic Electric in 1948.

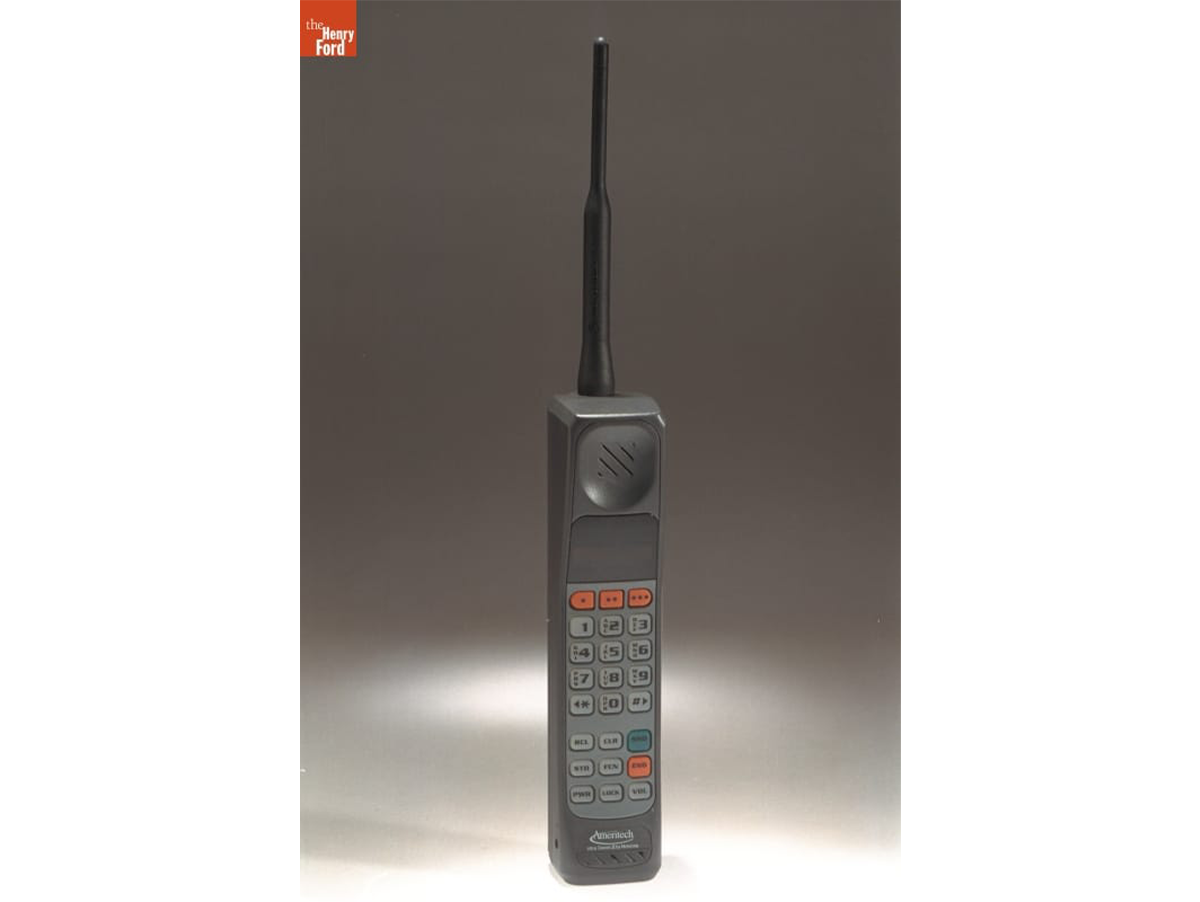

Motorola Brick Phone, 1985 / THF97588

Motorola Brick Phone, 1985 / THF97588

On April 3, 1973, Motorola engineer Martin Cooper made the first publicized cell phone call—to Joel Engel, who was working at AT&T trying to develop the same technology, which would allow users to make calls without having a physical connection to a network, unlike previous phones. While the car phone—a device that was mounted in the trunk of a car, with cables running through the vehicle to connect to a headset in the cabin—already existed and allowed for some mobile communication, its adoption was intentionally limited by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which required licenses for its use. Motorola continued refining their cellphone technology, and in 1983 they had the first commercially available cellphone ready for the market. By 1990, over one million Americans were using cellphones.

Pay phones and mobile phones help people get in touch on the go. But what about when the recipient, not necessarily the caller, is out and about? For that, we turned to different technologies—including the answering machine and the pager.

AT&T Model 2100 Telephone Answering Machine, circa 1983 / THF323526

AT&T Model 2100 Telephone Answering Machine, circa 1983 / THF323526

Although the first automatic answering machine was invented in 1935, the first commercially viable machine didn’t arrive until 1971, with PhoneMate’s Model 400. By the end of the 1980s, one in three American households owned an answering machine. While the concept may seem simple, the implications for telephone culture were immense. Now there was a way to be continuously available; even if you were away from your telephone, the machine would make sure that the caller’s message was there waiting for you when you returned. The adoption of answering machines also led to a change in the culture around phone calls. On the one hand, calls were easier to screen, but on the other, a missed call no longer meant the onus was on the caller to try again, but rather on the recipient to phone back.

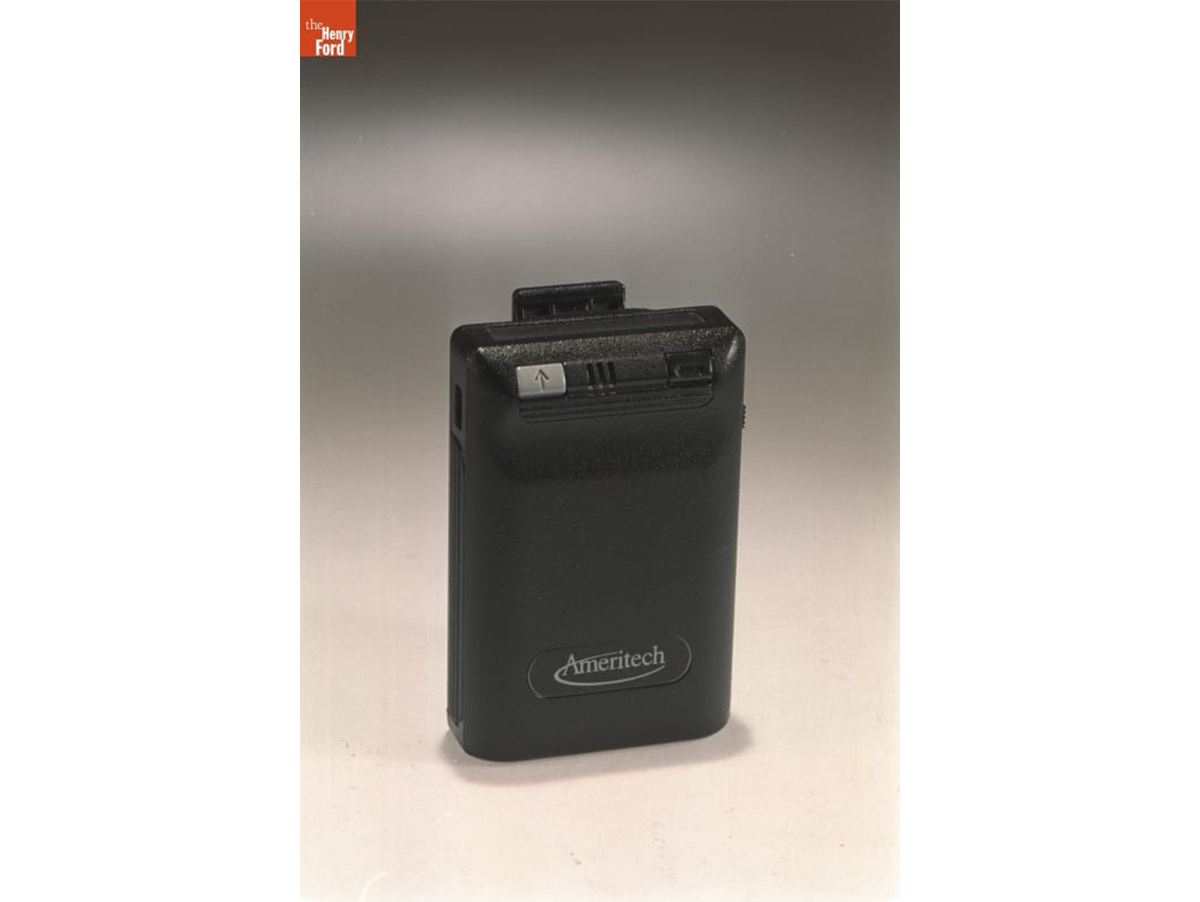

Motorola Pager, 1995 / THF302299

Motorola Pager, 1995 / THF302299

In 1949, wireless communication pioneer Al Gross patented the very first telephone paging device. The following year, the device was put into service at New York's Jewish Hospital—marking the start of what would be a long history of use in critical communications. In 1959, Motorola coined the term “pager,” and the name stuck; in 1964, they would become the main force in the pager market with the first versions available to consumers. While the first pagers delivered tone-only messages, by the 1980s new versions had been developed that displayed alpha-numeric messages, allowing people to send short messages without having to pick up a phone. By 1994, over 61 million pagers were in use. Although the rise of cell phones with the ability to send text messages led to pagers falling out of favor with the general public, pagers remain a crucial part of many hospitals' and first responders' communication systems.

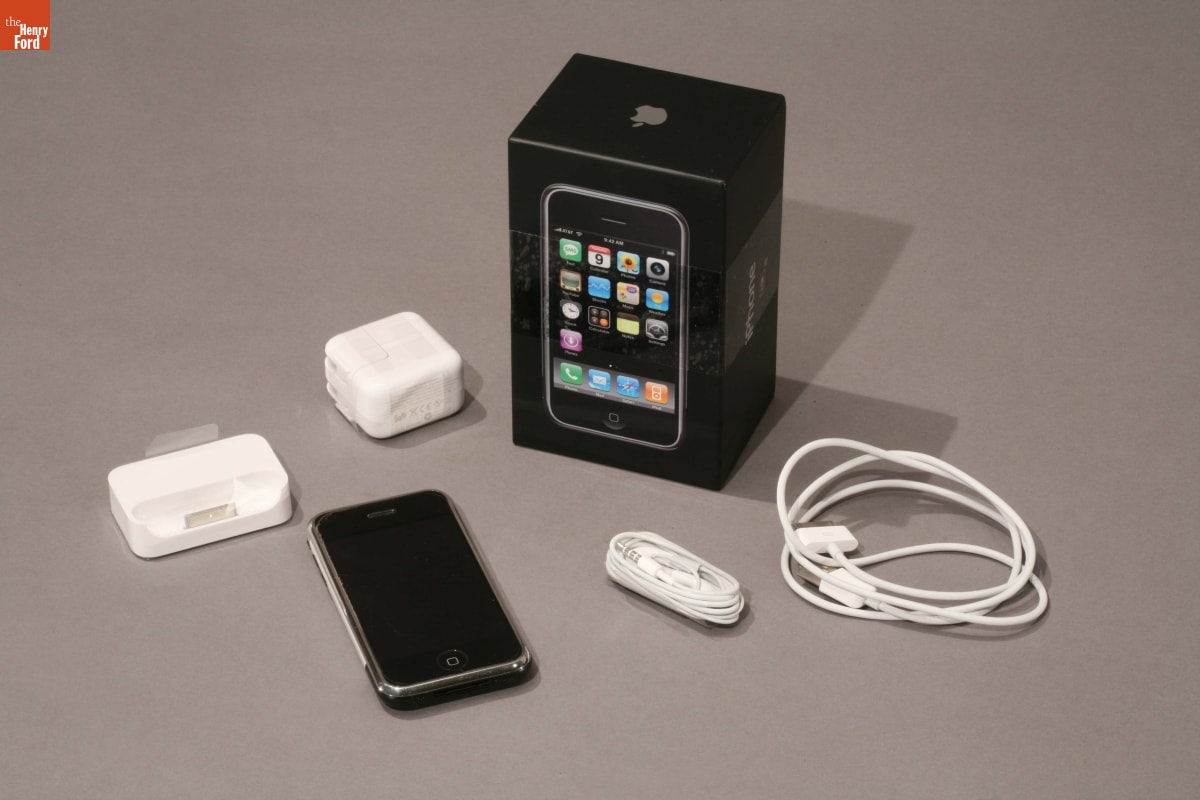

iPhone, 2007 / THF92290

iPhone, 2007 / THF92290

Of course, thanks to the smartphone, our telephone technology now solves more problems than ever before, all in a conveniently portable package. Landline telephones have waned in popularity, and for many of us, our mobile phone is now our only phone. We can text paragraphs of thoughts with a few swipes on a screen. Our phones not only automatically come with a voicemail function, but many of them will even transcribe the messages for us. We’re more reachable than ever before, yet many of us talk on the phone even less. The remnants of the technology that led to this moment still exist, though—just waiting for us to make the connection.

A functioning pay phone can still be found—and used!—in the Welcome Center at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by Rachel Yerke-Osgood

A functioning pay phone can still be found—and used!—in the Welcome Center at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by Rachel Yerke-Osgood

The Henry Ford's 1898 pay telephone was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Servcies (IMLS).

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

George Balanchine and Ballet in America

If you are a fan of American ballet — be it regularly attending productions, seeing The Nutcracker at Christmas, or simply imagining what it would be like to be a prima ballerina — then you have likely engaged with the legacy of one of the dance world’s most important figures: George Balanchine.

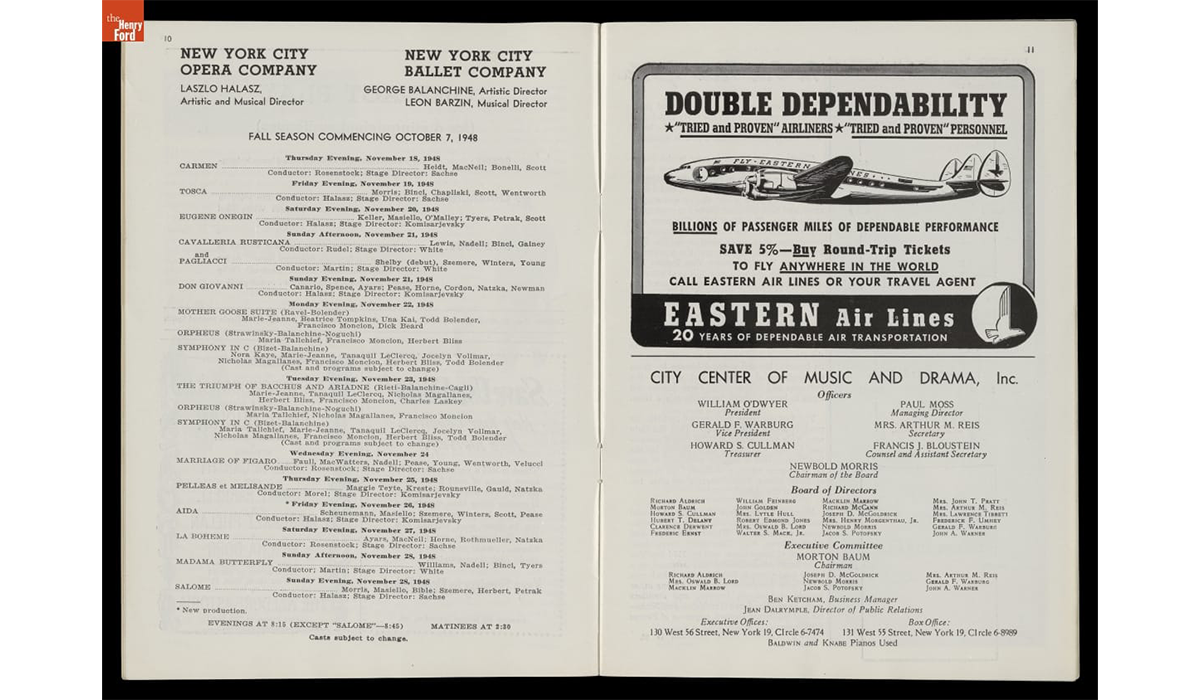

Program from New York City Center of Music and Drama, November 1948, featuring New York City Ballet’s schedule of Balanchine-choreographed performances / THF715566

Program from New York City Center of Music and Drama, November 1948, featuring New York City Ballet’s schedule of Balanchine-choreographed performances / THF715566

George Balanchine was born Georgiy Melitonovich Balanchivadze on January 22, 1904, in St. Petersburg, Russia. "He was exposed to the arts from birth, as his father was as his father was Meliton Balanchivadze, Georgian opera singer, composer, and founder of the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre. His Russian mother, Maria, was also a lover of ballet, and although she thought her son would eventually join the military, she insisted that he audition for dance. At age nine, Balanchivadze was accepted into the Imperial Ballet School at the Mariinsky Theatre. Throughout his early years at the school, Balanchivadze already started to work on his choreography. In 1920 he debuted his first piece — a duet, La Nuit, which was met with some disapproval from his school's directors.

When Balanchine was born, ballet was seen as a way of rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg society. The city was the cultural center of Russia, and remained so throughout World War I (when it was renamed Petrograd) and after the October Revolution (when it was renamed Leningrad). / THF208535

When Balanchine was born, ballet was seen as a way of rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg society. The city was the cultural center of Russia, and remained so throughout World War I (when it was renamed Petrograd) and after the October Revolution (when it was renamed Leningrad). / THF208535

After graduating, Balanchivadze enrolled at the Petrograd Conservatory, and worked at the State Academic Theatre for Opera and Ballet in their corps de ballet, before forming his own ensemble, the Young Ballet. The Soviet government granted permission for the group to travel around Europe, and they eventually settled in Paris. In 1924, Balanchivadze was invited to join the famous Ballets Russes as the main choreographer, quickly being promoted to ballet master of the company. It was here that he changed his last name to Balanchine, and shifted his focus exclusively to choreography after a knee injury.

After the bankruptcy of Ballets Russes in 1929, Balanchine found work with other European companies, and continued creating new pieces. In 1933, American writer and cultural figure Lincoln Kirstein convinced Balanchine to move to New York City. With Kirstein’s support, Balanchine founded the School of American Ballet, opening its doors in 1934 with the aim of providing more rigorous training for American dancers. In 1948, Balanchine and Kirstein founded the New York City Ballet. It was for this company that Balanchine would create perhaps his best-known work - his version of The Nutcracker.

When Balanchine first created his version of The Nutcracker, he returned to the stage in the role of Herr Drosselmeyer. / THF360453

When Balanchine first created his version of The Nutcracker, he returned to the stage in the role of Herr Drosselmeyer. / THF360453

Although it was not the first version of The Nutcracker to be performed in America - that distinction goes to Willam Christensen's 1944 staging for the San Francisco Ballet — Balanchine's 1954 production helped cement the ballet's popularity, and indirectly ensured the survival of ballet in America. His version is distinct from others in that “Clara” is called “Marie” (her name in E.T.A. Hoffman's original story) and it maintains the tradition of casting children for the roles of Marie and Drosselmeyer's nephew (who is also The Nutcracker that becomes the Prince), rather than casting adult principal dancers as became common in other productions. Today, annual performances of The Nutcracker are what keep many American ballet companies afloat, with ticket sales for performances constituting approximately forty percent of their yearly revenue; it is Balanchine's version that remains the most popular staging.

Famed dancer Maria Tallchief — the first major American prima ballerina, and a member of the Osage nation — was lauded for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker. She is often credited alongside Balanchine with revolutionizing American ballet. / Seen here at top right, THF715558

Famed dancer Maria Tallchief — the first major American prima ballerina, and a member of the Osage nation — was lauded for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker. She is often credited alongside Balanchine with revolutionizing American ballet. / Seen here at top right, THF715558

During his career, Balanchine founded several ballet schools, companies, and nonprofits. They include the previously mentioned School of American Ballet (1934-present) and New York City Ballet (1948-present), the American Ballet (1934-1938) which later joined with the American Ballet Caravan (1936-1941), and the Ballet Society (1946-present). Balanchine also served as the principal choreographer for Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo from 1944 to 1946.

In 1964, the Ford Foundation gifted almost $8 million to support professional ballet in America; nearly all of it went to Balanchine-affiliated companies. His choreographic work was prolific, as he created 400 individual works, many of which remain in the canon of ballet companies in America and abroad. He was also known for his choreography for Broadway and Hollywood productions, and for collaborating with the likes of composer Igor Stravinsky and designer Isamu Noguchi (who would continue working in the dance world by partnering with Martha Graham) for his productions.

For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, Ford Motor Company hired American Ballet Caravan to perform A Thousand Times Neigh, a ballet telling the story of the automobile through the eyes of Dobbin the horse. The dancers had been trained at Balanchine’s American Ballet. /THF215723

For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, Ford Motor Company hired American Ballet Caravan to perform A Thousand Times Neigh, a ballet telling the story of the automobile through the eyes of Dobbin the horse. The dancers had been trained at Balanchine’s American Ballet. /THF215723

Balanchine’s impact on ballet in America is almost impossible to overstate. Writing for the New York Times after his death on April 30, 1983, Anna Kisselgoff called George Balanchine “one of the greatest choreographers in the history of ballet ... [who] established one of the foremost artistic enterprises the United States has called its own.” The Georgian immigrant became known as the father of American ballet, as his choice to move beyond the classical style of his original training created a distinctly American style, one that rejected classical models and instead embraced artistic expression and dance for its own artistic and athletic sake, rather than as just a storytelling medium. This focus on athleticism and aesthetics, though, did not come without cost. Through his prolific work, Balanchine’s ideal dancer — long-legged and extremely thin — became the standard for American ballet. The pressure for ballerinas to be almost preternaturally thin persists to this day, and eating disorders and body dysmorphia are sadly not uncommon.

The story of American ballet — for better and for worse — is in so many ways the story of George Balanchine.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Women in Service: From the Civil War to WWII

Throughout history, women have served their country during war and in peacetime, on the home front and at the front lines. Since the founding of this country, both military and civilian women contributed to their nation’s cause—whether through active service, or by using their talents and time to support our fighting forces from afar—in ways that were and are often overlooked. Through these objects from the collections of The Henry Ford, we can explore some of these important stories, shedding light on women and their service.

Frances Clayton

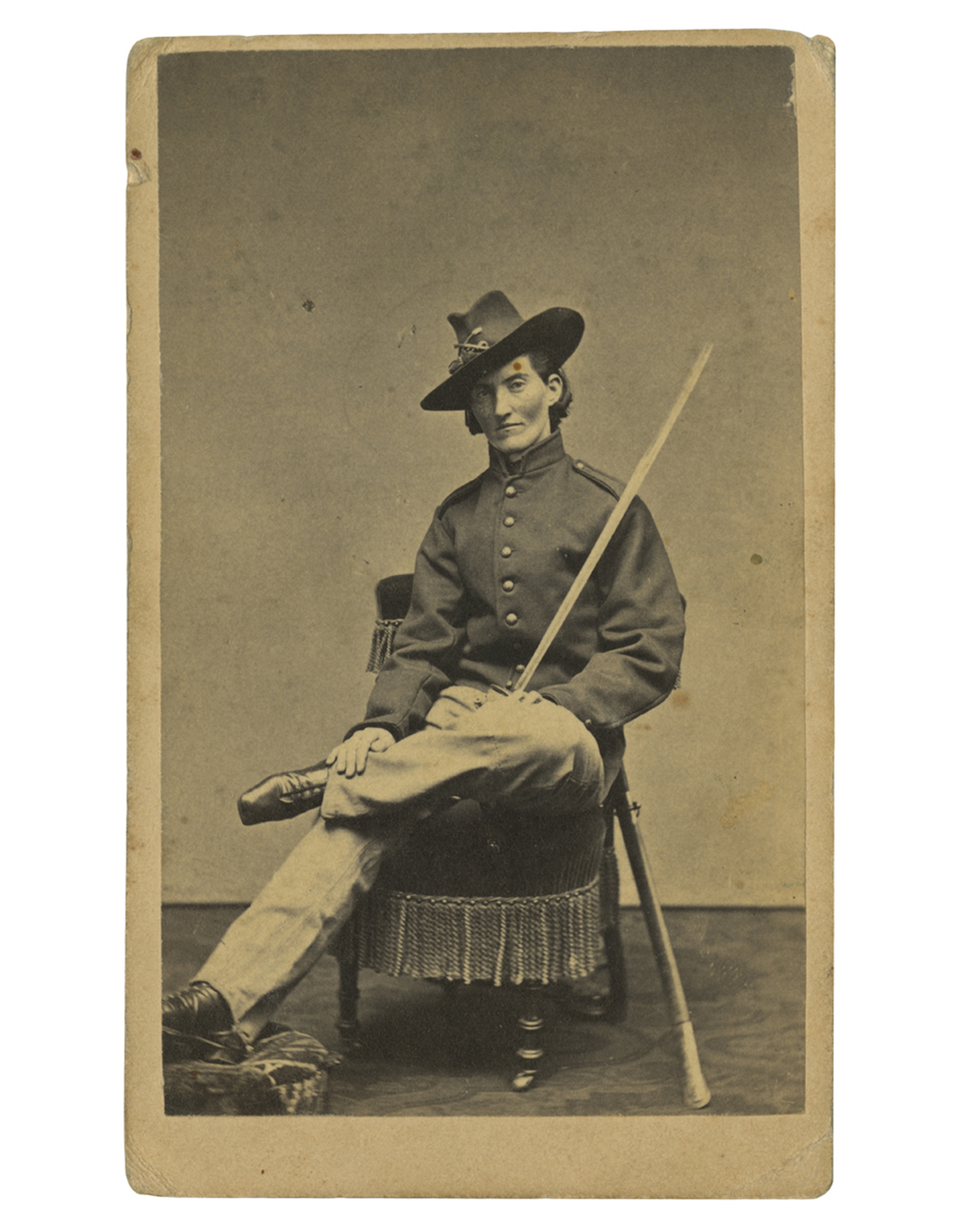

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

While women could not officially serve in combat roles in the United States until 2016, women participated in combat as early as the American Revolution—dressed as men.

During the Civil War, hundreds of women concealed their identities to enlist and fight in battles across the country. Their motivations varied: some wanted to stay close to husbands, brothers, or other loved ones, while others sought to defy societal norms, pursue adventure, or earn a soldier’s pay and enlistment bounty. Patriotism was another driving force—with northern women supporting the Union or abolitionist causes, and southern women joining to support the Confederacy.

At the time, joining the military was easier. With an urgent need for soldiers, physical exams were brief, and no identification was required. A woman could cut her hair, wear men’s baggy clothing, and adopt a male alias. Some were eventually discovered and sent home, others were wounded or killed during service, and others returned home, mustering out at the end of their service.

—Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator

WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps

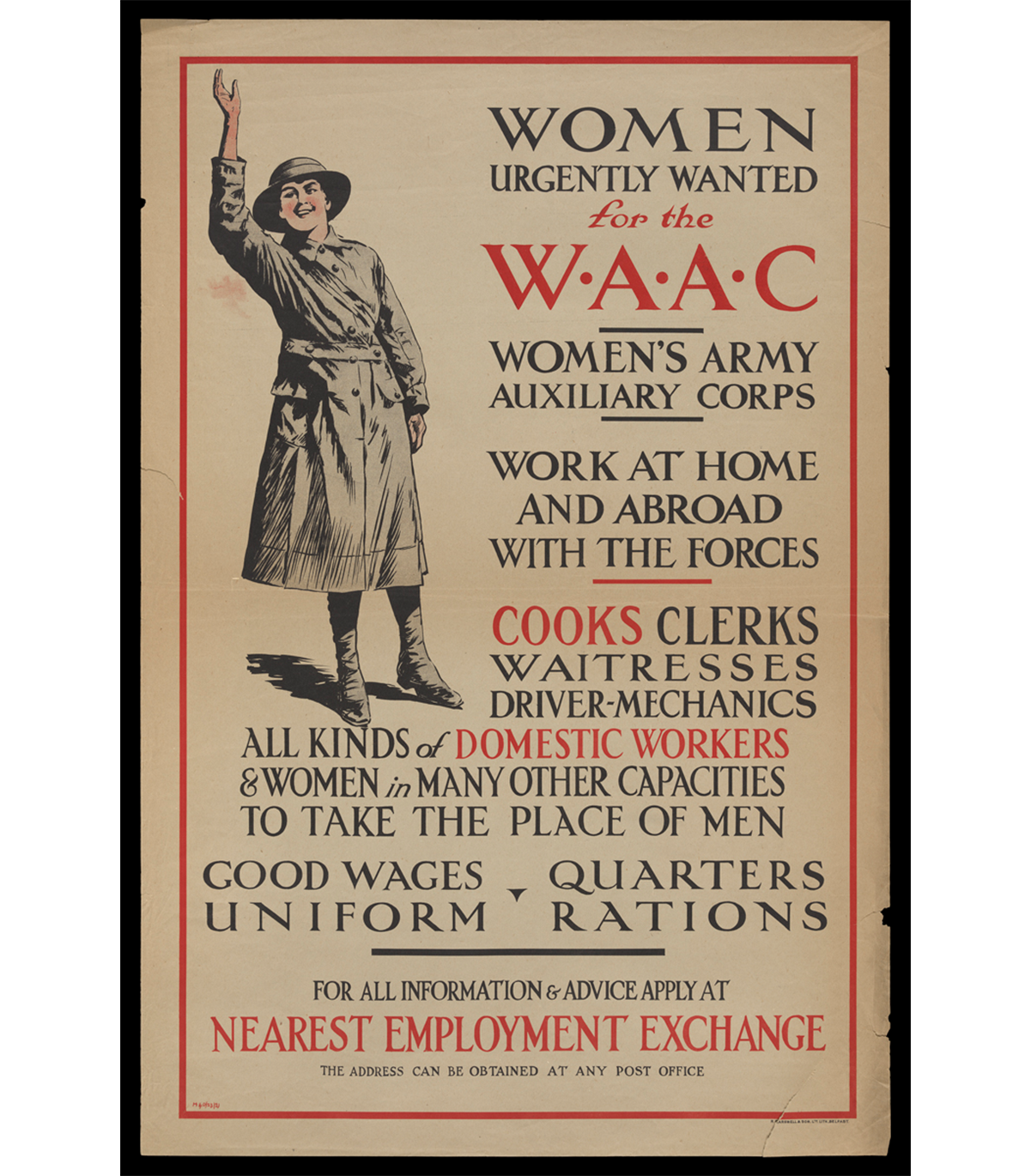

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

Over 50,000 British women volunteered with the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1917 and 1918, the final two years of the First World War. WAAC volunteers took on support roles such as administrative work, catering, or vehicle maintenance at home in the United Kingdom and on the front in France and Belgium. In doing so, WAAC freed up British men on the front from non-combative tasks so the military could focus on the battlefield. This was the first time that women were allowed in the British armed forces in an official capacity outside of nursing.

The corps was renamed Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1918 after Mary of Teck, the queen consort of King George V, became the corps patron. The original WAAC/QMAAC disbanded in 1921, but it inspired women's auxiliary military corps in Great Britain and the Commonwealth and in the United States during the Second World War.

—Kayla Chenault, Associate Curator

“Molly Pitchers”

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

"Molly Pitcher" was the symbolic name given to several historic women who served during the Revolutionary War. These women, usually a soldiers' wife, were noted for carrying water and other provisions to frontline troops. But they became more famous for fighting alongside other soldiers after their husbands or loved ones had fallen in battle.

During the Second World War, August 4, 1943, was designated Molly Pitcher Tag Day. On that day, thousands of women throughout the United States dressed in early American or patriotic costumes and became contemporary "Molly Pitcher" heroines by selling war stamps and bonds. At Greenfield Village, Women's Army Corps recruiters from Detroit, Michigan, and four "Molly Pitchers" came together to raise money for the bond drive, shining a light on women's contributions—whether on the home front or in military service—to America's war efforts since our country's founding.

—Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator

Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

Husband-and-wife designers Charles and Ray Eames spent the early years of their partnership experimenting with molding plywood for use in furniture and sculptural objects. In the early 1940s, they used the spare bedroom in their Los Angeles, California, apartment to develop a machine to mold plywood using pressure. A friend, Dr. Wendell Scott of the Army Medical Corps, visited the Eames’ home and saw the potential of molded plywood for the war effort. America’s entry into World War II had created material shortages, including metal. Despite the shortage, metal splints were being used for broken limbs on the battlefield even though they were inflexible and heavy, and worsened wounds in transport.

Upon hearing this, the Eames designed a flexible, lightweight and durable leg splint using the same molded plywood technology they were developing for plywood furniture. They presented their prototype splint to the U.S. Navy and worked with them to further modify and perfect the product. By 1942, the Navy had placed an order for 5,000 splints. The Eames Leg Splint became a successful medical innovation and a design artifact, as well as a critical step in the Eames understanding of molded plywood.

—Adapted from What if Collaboration is Design? Katherine White, Curator of Design

Lillian Schwartz, Nurse Cadet

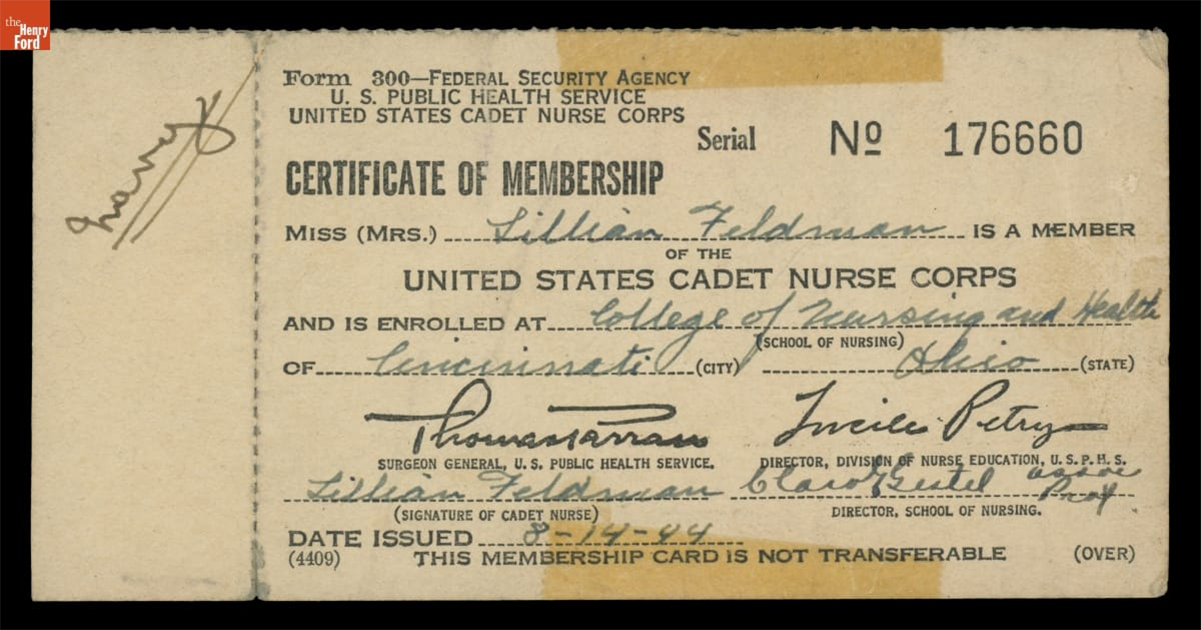

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Feldman Schwartz (1927-2024) was an American artist who began working at the forefront of computer art and experimental film in the late 1960s at Bell Laboratories. Before her art career was established, however, her life was entwined and impacted by service in the medical field during the last years of WWII, and in its immediate aftermath.

In 1944, when Lillian was 17, she applied to the United States Cadet Nurse Corps—a tuition-free program designed to address the WWII nursing shortage. Lillian did well in her coursework, but she quickly realized that she struggled with nursing people. Despite this, she found ways to bring joy into the Cincinnati hospital where she worked by painting murals in the children’s ward and making plaster sculptures in the cast room. Lillian quickly realized that she was an artist, not a nurse. While working in the hospital pharmacy, she met an intern named Jack Schwartz, whom she would marry in 1946. In 1948, Jack was stationed in Fukuoka, Japan, and Lillian traveled to join him after the birth of her first son. Unfortunately, she developed polio symptoms several weeks after her arrival, and in the post-war aftermath, she was also exposed to the lingering effects of radiation from the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These experiences led to serious health issues throughout her life and were often referenced in her art projects and writing.

—Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

This collaborative blog was written by the staff of The Henry Ford

by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Aimee Burpee, by Rachel Yerke-Osgood, by Andy Stupperich, By Kayla Chenault, by Katherine White

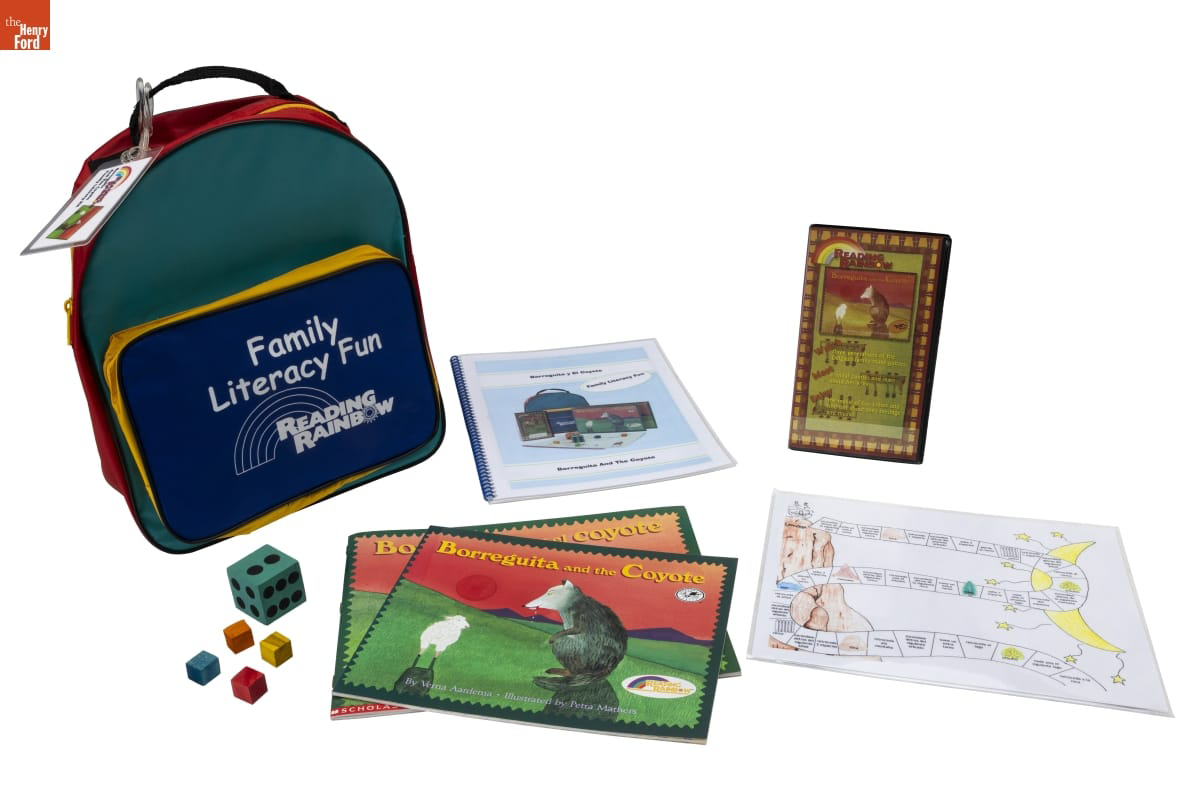

Assembled by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), this colorful backpack contains English and Spanish language versions of the book Borreguita and the Coyote, a VHS tape of a television episode centered around the book, and bilingual activity booklet and board game designed to let families practice their language skills together. This kit was likely given to a library, community center, or school for distribution, before eventually making its way into The Henry Ford’s collection in 2024. It represents an extension of the efforts to promote children’s literacy and love of reading undertaken by a program that would come to influence a generation of children: the Reading Rainbow television show.

Reading Rainbow "Borreguita and the Coyote" Family Literacy Kit, 1999-2008. / THF198380

First airing in 1983, Reading Rainbow was developed to address the problem of children losing their reading comprehension skills over the summer break. Hosted by LeVar Burton, each episode focused on a different topic related to a featured book, and consisted of live-action segments with Burton, a celebrity narrating the chosen book, and recommendations for similar books that viewers could check out at their local library.

In the show’s early days, television was viewed as the enemy to education, and the show creators encountered initial skepticism. Despite this, and thanks to funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, throughout its 23-season run Reading Rainbow demonstrated that it did, in fact, boost children’s reading skills. As the show progressed, it was able to tackle more difficult issues, with notable segments including footage of a live childbirth, and LeVar Burton talking to the students of PS 234 as they returned to their school after being forced to leave in the aftermath of 9/11.

Season 6 episode “Robbery at the Diamond Dog Diner” saw Peter Falk reading the picture book, of the same name, and LeVar getting roped into working at a diner. This letter to “Dinerman” Richard Gutman, and other correspondence, indicates that he was helpful to the production team in their search for a diner to film in — a testament to the research the Reading Rainbow team put into their live segments. / THF715225

Despite its immense popularity — the show would receive over 250 awards including a Peabody and 26 Emmys and earn the title of the most-watched PBS program in classrooms — Reading Rainbow faced new challenges with the 2002 passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, which shifted funding from programs that taught children to love to read, and toward programs that taught them how to read. The final original episode aired in 2006, although reruns would continue until 2009.

Like so many objects in The Henry Ford’s collection, this kit allows us to tell multiple stories. It allows us to talk about one type of literacy. It adds to our collections related to popular children’s television shows. It gets to the experience of immigrants in America as they try to learn another language. All of these are valid lenses through which to view this kit, and all were cited as reasons why it belonged in our collection.

At The Henry Ford, we share something in common with Reading Rainbow — the belief that objects, like books, can expand our horizons through the stories they tell. But you don’t have to take our word for it!

To learn more about Reading Rainbow, check out the documentary Butterfly in the Sky. You can also find story segments from Reading Rainbow, along with related activities, on the Reading Rainbow website.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

"Long Live" and Prosper: Fandom in Pop Culture

Have you ever decked yourself out in head-to-toe colors of your favorite sports team? Discussed theories about your favorite TV show? Celebrated a fictional holiday like Festivus, wished someone “May the Fourth be with you,” or worn pink on Wednesdays? If so, then you’ve participated in fandom.

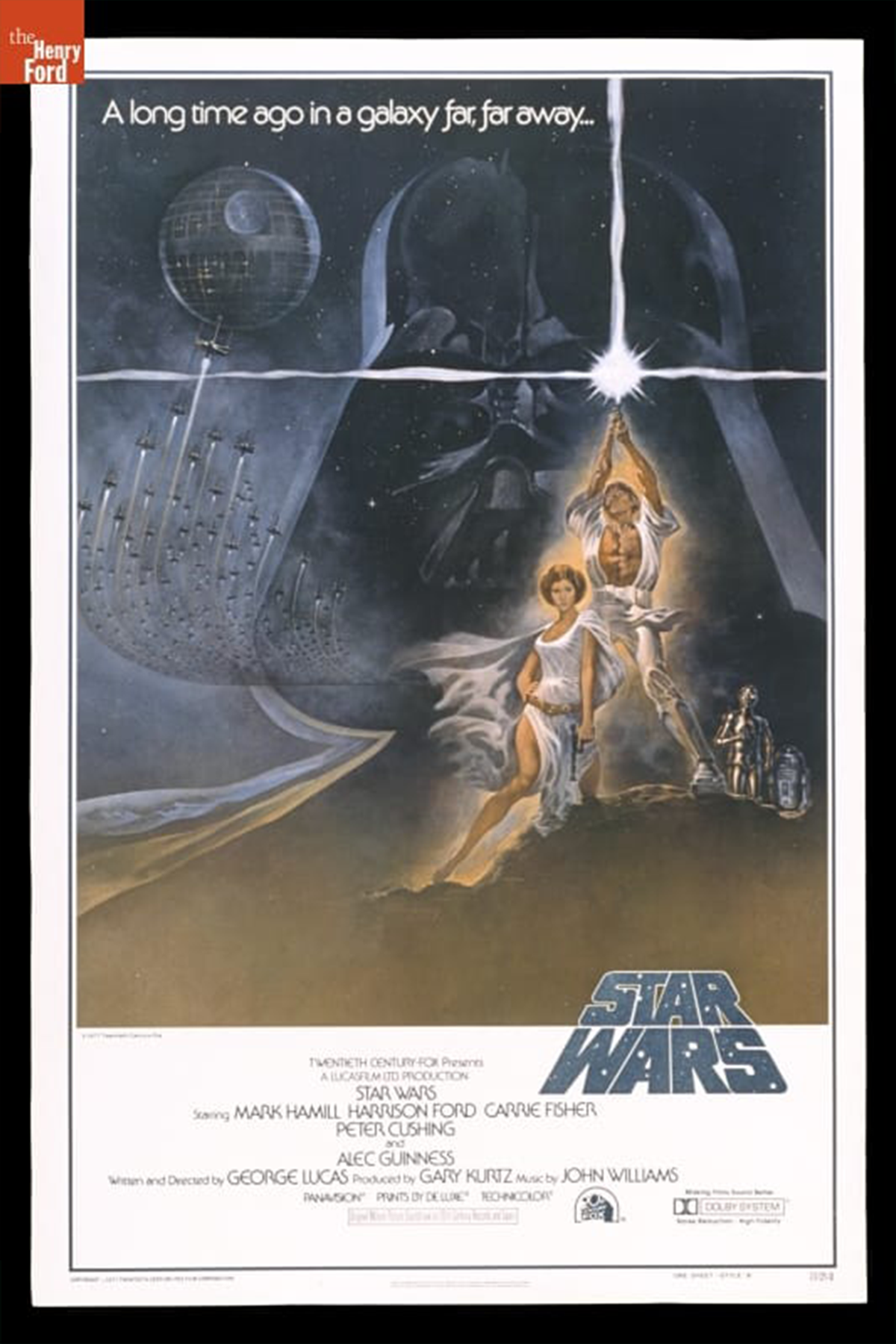

On May 4th of each year, Star Wars fans celebrate Star Wars Day. Once a grassroots, fan-led celebration, it has been embraced by Lucasfilm and Disney and bled over into the popular consciousness. / THF95553

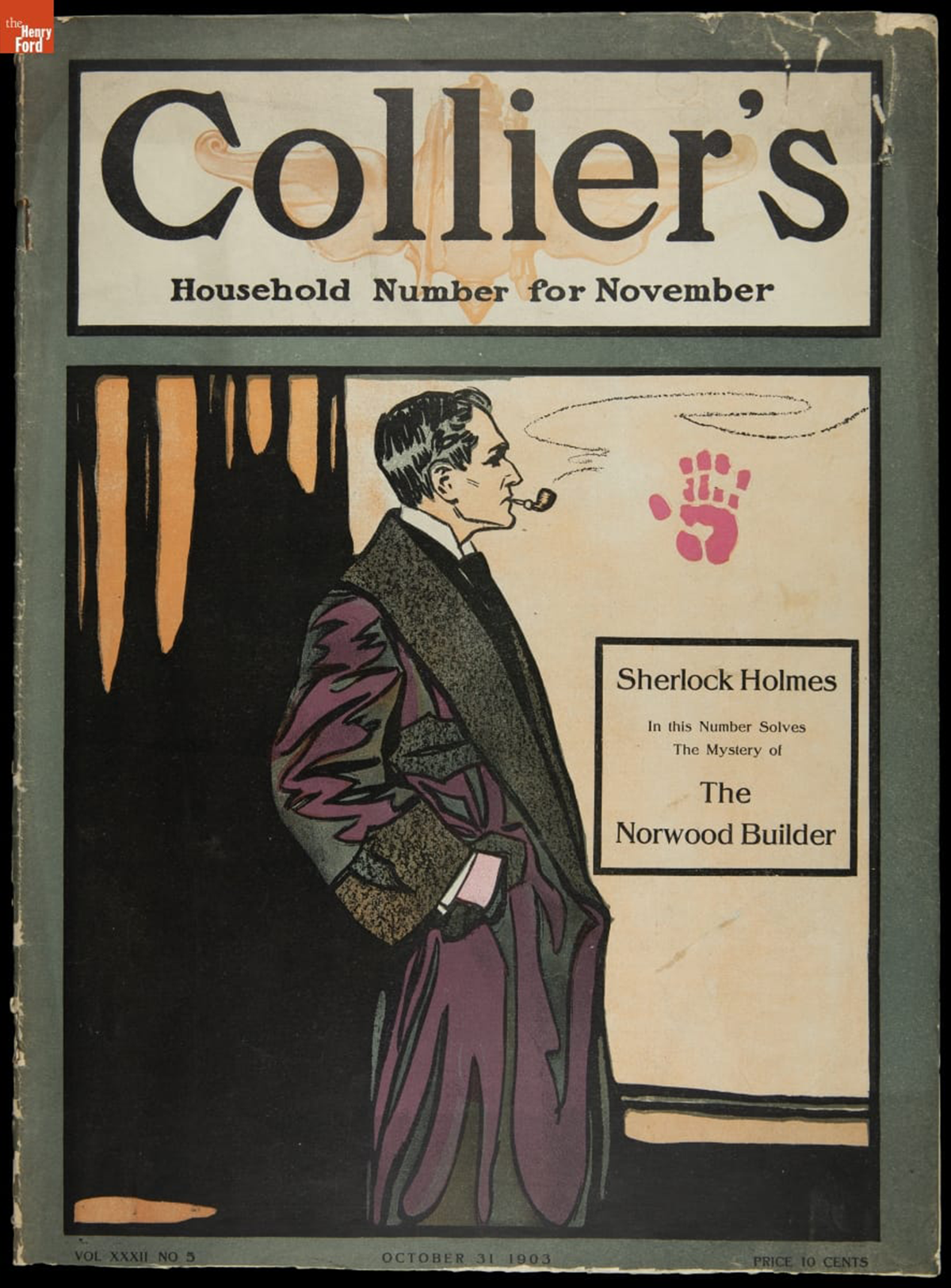

The idea of fandom — a group of fans of something or someone, particularly enthusiastic ones — can trace its roots back to the literature of the 1800s and early 1900s. In 1894, literary scholar and critic George Saintsbury coined the term “Janeites” to refer to the most intense devotees of the work of Jane Austen. In 1903, after receiving numerous letters from the character’s devoted fanbase (and after 20,000 readers cancelled their subscriptions to The Strand, in which his stories were published), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle brought Sherlock Holmes back to life, eight years after killing the character off in hopes of moving on to other projects. Doyle’s “resurrection” of Sherlock Holmes is perhaps one of the earliest examples of fandom shaping the work that it so adores.

Sherlock Holmes’s popularity has lasted well beyond his own “lifetime.” He has been portrayed in film and television over 250 times, and is often treated as a real historic figure, despite his fictional nature. / THF722711

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, fandom communities began to coalesce around the stories published by Hugo Gernsback in Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine. Gernsback published the letters and addresses of fans who sent in mail to the magazine, allowing fans to begin writing to each other, too, meeting up whenever possible. In 1934, Gernsback created the Science Fiction League, a correspondence club for fans of the genre. The Philadelphia Science Fiction Conference was held in 1935, arguably the first of what would become known as “fan cons,” or fan conventions.

Science fiction remained a fertile ground for fandom. In the 1970s, fans of shows like Star Trek began to focus on the relationships between characters, producing creative works like fan fiction and ”fan vids” that explored character dynamics beyond what was presented in the original media. / THF362462

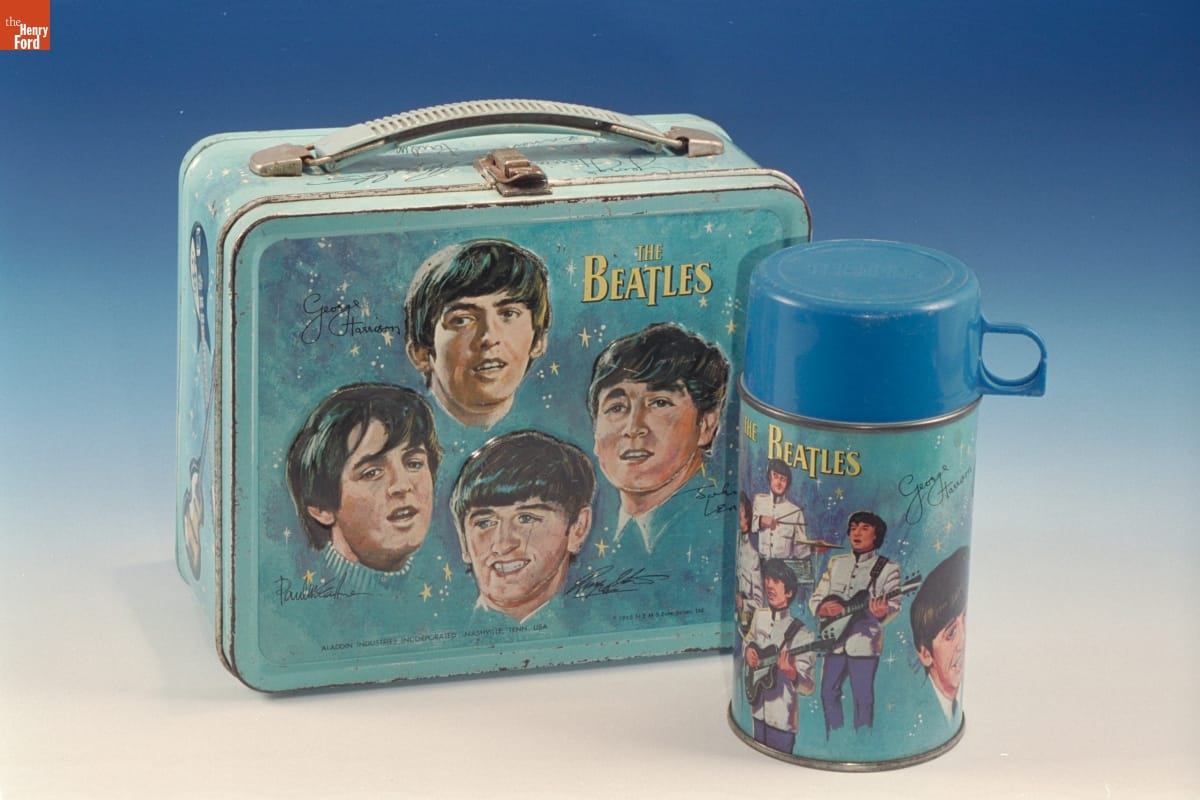

The bar for fandom in music was set by Beatlemania. From 1963 to 1966, young, passionate, female fans of The Beatles created a subculture unlike any the world had previously seen. Originally, Beatlemania was confined to Britain; the phenomenon went international, though, with the band’s appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Everywhere the Beatles went, they were followed by screaming fans, captivated by the band’s memorable hooks, accessible themes, and on-stage charisma. This fervor would last until the group’s last stadium concert in 1966. Beatlemania created the template that later boy bands would seek to imitate, and screaming female fans became a staple of boy band concerts into the 21st century.

At the peak of Beatlemania, there was a plethora of Beatles memorabilia available on the market – whether you wanted to represent the band as a whole, or a particular favorite Beatle. / THF92312

Fandom can be more than just a one-way street. The relationship between Taylor Swift and her fans — dubbed “Swifties” — has changed the face of fandom, both inside and outside of the music industry. Throughout her career, Swift has interacted with her fans on social media, teased upcoming projects with “Easter eggs” for them to decode, and at one point even invited them to “Secret Sessions” — exclusive, invitation-only listening parties where select fans, handpicked by Swift, were the first to hear her soon-to-be-released albums. In return, Swift’s fans have catapulted her to incredible heights of success. The relationship between artist and fandom, however, is not without concern, as Swift herself has alluded to the parasocial extent to which some fans have taken the relationship.

In 2024, Time magazine named Taylor Swift their Person of the Year. The level of fandom surrounding her that year was such that she became what writer Sam Lansky called “the main character of the world." / THF722029

History shows that fandoms have the power to shape popular culture. But why do people join fandoms? The same themes — the feeling of acceptance, understanding — crop up in many discussions around the question. So, too, does the topic of escapism — using another world, or even another person, as a distraction from the stress of one’s own life. It is part of human nature to seek inclusion and comfort, to feel as if we belong as part of a group, that we have found a safe space. Perhaps this, then, is the role that fandoms fill, and why they remain a recurring part of our stories.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Pattern, Paint, and Peacocks: An Introduction to the Whimsical Art of the Pennsylvania Germans at The Henry Ford

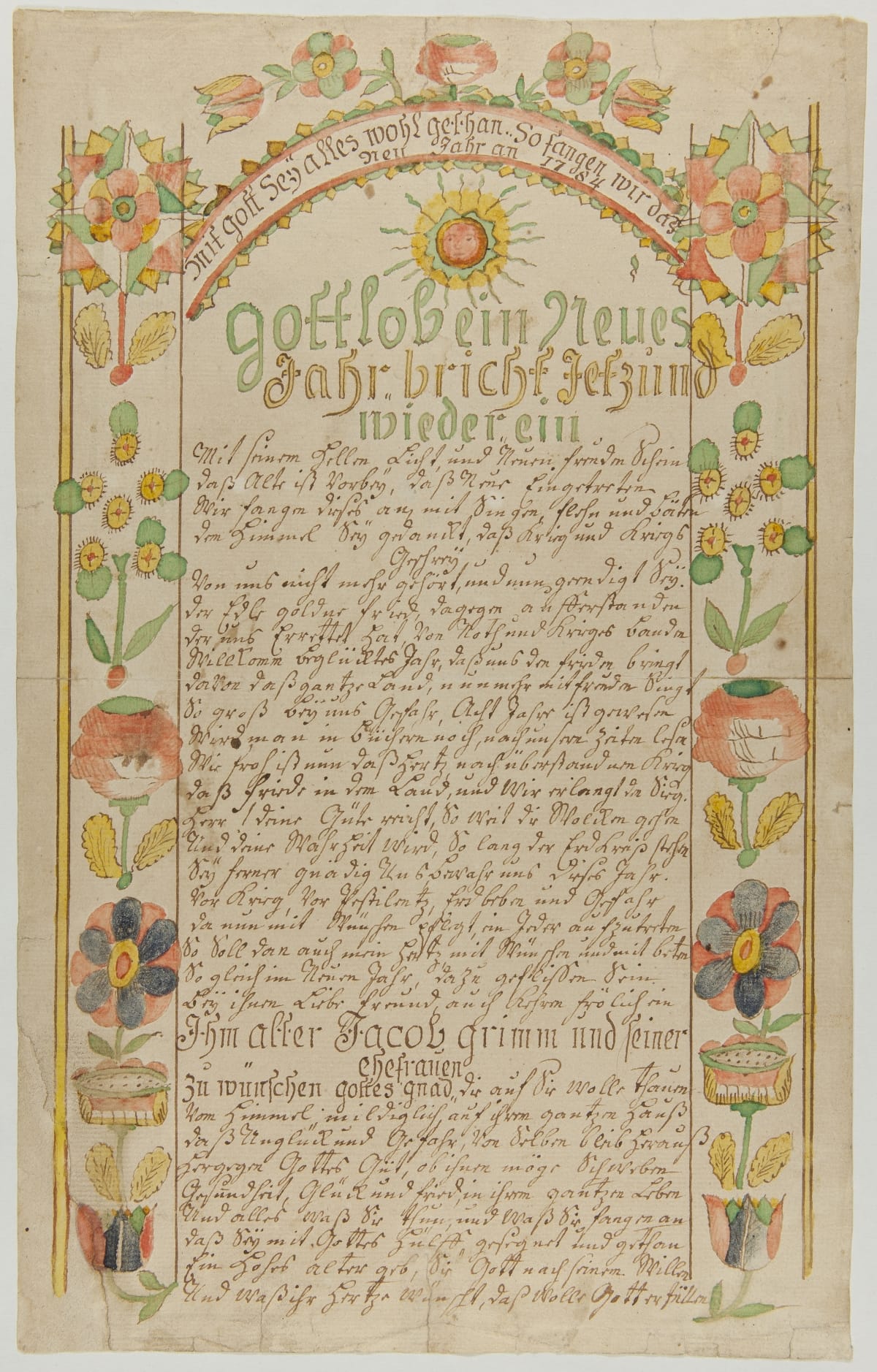

New Year’s Wish for Jacob Grimm and Family, 1784, made by Daniel Schumacher (active 1728-1787), worked in Berks, Lehigh, and Northampton Counties. 61.148.1 / THF237518

The Pennsylvania Germans, popularly known as the Pennsylvania “Dutch” (a corruption of the German word “Deutsche,” which literally means German) were a vibrant immigrant community active in southeastern Pennsylvania in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. By 1790, they made up about forty percent of the population and vied with those of British ancestry as the largest ethnic group. Even in urban areas, such as Lancaster and Philadelphia, the Germans were a sizeable minority.

Within the community itself there was great diversity, although many immigrated from the Palatinate area of southwestern Germany and approximately ninety percent were Protestants, with only ten percent Catholics.

What is remarkable about their legacy is their flamboyant, whimsical, playful, and highly imaginative folk art. They loved to decorate just about every type of household object, from small-scale items like ceramics to large-scale pieces like furniture, with instantly recognizable images. These artists are the most renowned among folk art collectors for their illuminated manuscripts, including marriage and birth certificates, family registers—essentially any type of recorded document. These pieces are called Fraktur.

The Compositions:

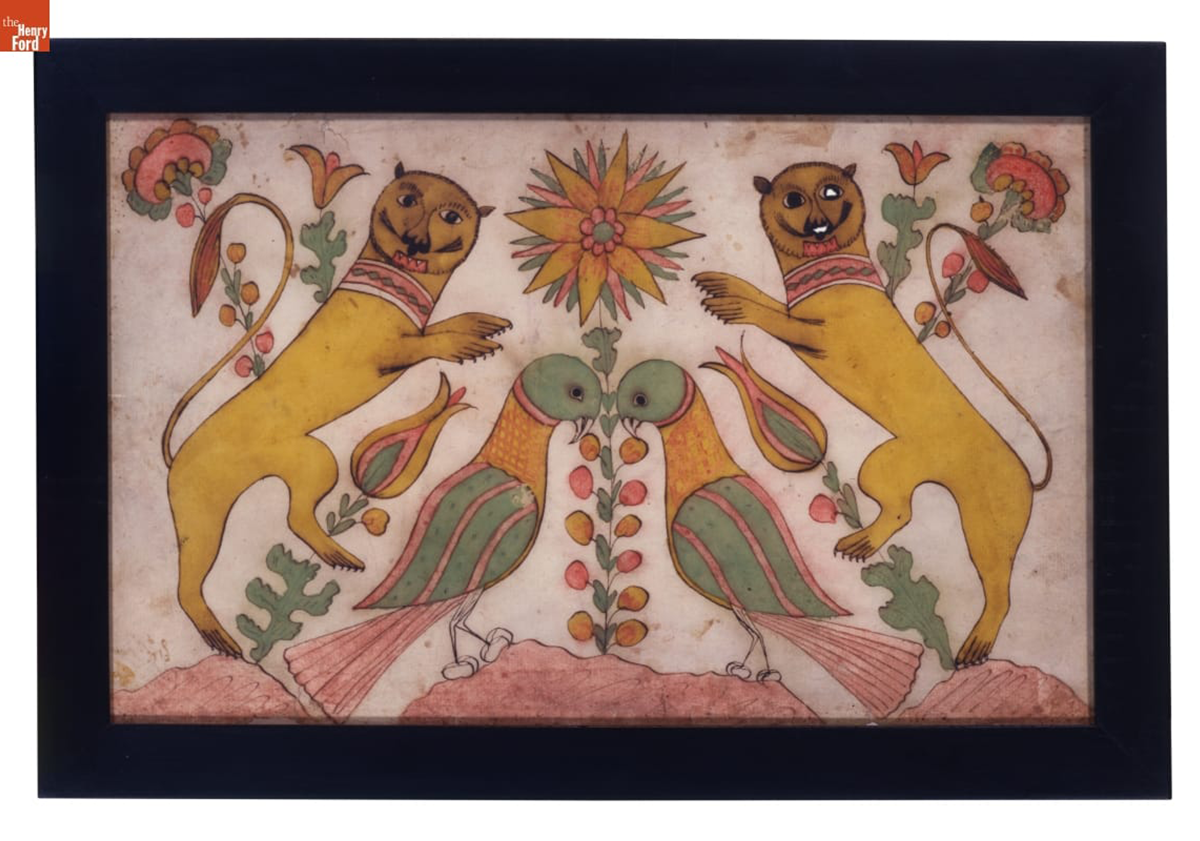

Confronted Lions and Birds, 1800-1820, made by Daniel Otto (active c. 1792-1822) Haines Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, pen and ink and watercolor on woven paper, 00.3.3038 / THF119526

This Fraktur by Daniel Otto features a stylized central flower where everything on either side balances completely. This symmetry is the hallmark of folk art in general, and Pennsylvania German art in particular. Also note the whimsy or playfulness in the lions—they hardly look ferocious. This is yet another characteristic of Pennsylvania German art.

Decorative Motifs:

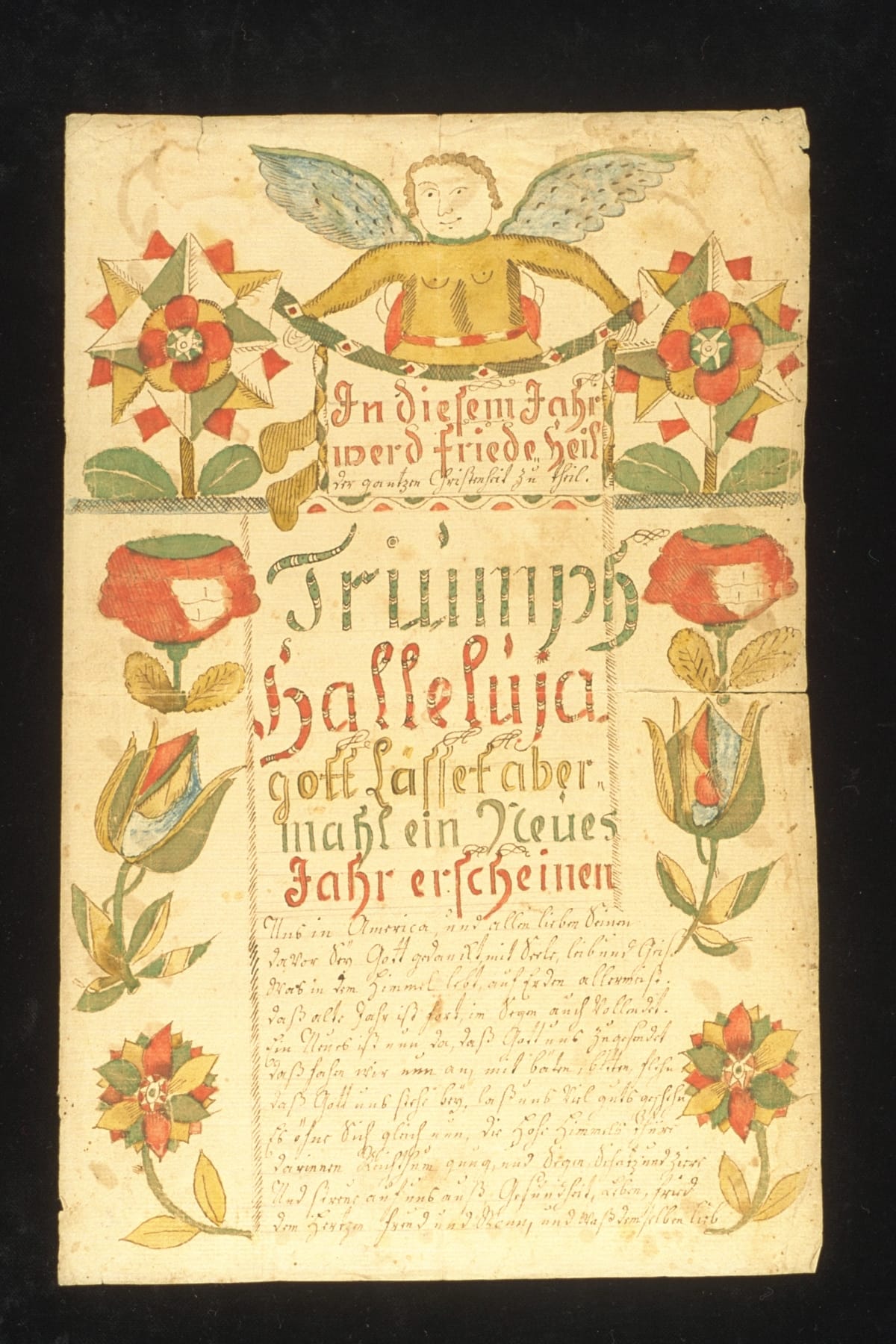

A New Year's Wish for Jacob Grimm and Family, circa 1775, made by Daniel Schumacher (active 1728–1787), worked in Berks, Lehigh, and Northampton Counties, 82.114.5 / THF305642

Notice that this piece, essentially an 18th-century New Year’s card, is symmetrically arranged around the text in the center. The highlight is the angel at the top. What is remarkable are the floral elements on either side. Tulips and stylized flowers are iconic design elements that appear in virtually every piece of Pennsylvania German art.

Another good example is this ceramic storage jar:

Storage jar, made between 1785-1796, made by George Hubener (1757-1828) Limerick Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 59.134.1 / THF177128

At the center of this jar, we find another peacock—which are in fact the 'confronted birds' in the second image above. Here, peacocks stand on the branches of a tree or bush. Notice that on either side, the floral branches terminate in tulip blossoms. Like peacocks or other stylized birds, the tulip is a motif frequently seen in Pennsylvania German folk art.

Reverse side of Storage jar, made between 1785-1796, made by George Hubener (1757-1828), Limerick Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 59.134.1 / THF177132

When we look at the reverse side of the jar, we see a variation of the image on the front. Of course, everything is arranged symmetrically, but instead of a bird at the center, we find a tulip blossom in its place. The space where the tulips were on the front side is now filled with abstracted floral elements.

The same use of symmetry is visible in this image of confronting peacocks:

Confronted Peacocks, 1800-1820, made by Daniel Otto (active c. 1792-1822), Haines Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, pen and ink and watercolor on wove paper, 29.2085.1 / THF119532

Plate, dated 1818, made by Andrew Headman, (active about 1756-1830), Rockhill Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 56.54.1 / THF191114

This large plate, used primarily for decoration, is once again highly ornate, with a stylized star at the center. This is surrounded by a circle of triangles in red and green, which in turn is circled by a symmetrical row of ubiquitous tulips.

Furniture:

German American Wardrobe 1790-1800 59.80.1 / THF118499

Like all the examples we’ve seen, this wardrobe is decorated with flowers—some naturalistic, some stylized. It also uses reds against greens, like the plate above. Although called a wardrobe, or Schrank in German, it likely was used in a public room, like a parlor or dining room, where it was meant to impress guests. Of all the examples of Pennsylvania German folk art in the Museum’s collection, this is by far the largest and most impressive.

The Spreading Influence:

Album Quilt, probably made in southeastern Pennsylvania (perhaps in Chester County), circa 1850. One corner of this quilt carries an applied fabric strip with the inked inscription "Anne D. Morrison." 2016.22.1 / THF166494

By the middle of the 19th-century, the design vocabulary of the Pennsylvania Germans spread well beyond their community, encompassing the entire region. For example, we know that this “Album” quilt that utilizes the Pennsylvania German aesthetic was used by Anne Dawson Morrison (1798-1866), a prosperous Philadelphia Quaker.

These objects are just a small sampling of the large folk art collection of The Henry Ford. To see more, please go to https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Rachel Yerke-Osgood, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

"Everything I Do is Me" - Gwen Frostic

Greeting card created by famed Michigan artist Gwen Frostic, circa 1980 / THF719491

Born in 1906 in Sandusky, Michigan, Sara Gwendolen Frostic lived a many-faceted life. An unidentified illness contracted while still an infant—later assumed to be a mild case of polio, although it also may have been a fever that resulted in cerebral palsy—left Gwen with some physical differences; still, Gwen never considered herself disabled. After her family moved to Wyandotte in 1917, Gwen was exposed to both the sophisticated atmosphere of urban Detroit, and the lush botanical splendor of her family's garden. These two influences would be reflected throughout Gwen’s life, as she became both a successful businesswoman and a well-known advocate for nature.

Despite attending Michigan State Normal College and Western State Normal College (now Western Michigan University), Gwen left school without completing her degree, opting instead to create a metalworking business in her parents’ basement. Gwen’s talent soon drew attention: the Detroit YMCA asked her to teach metalworking classes, Clara Ford commissioned her to make two copper vases, and Monsanto requested that she create a piece for their 1939 World’s Fair display.

Greeting card created from linoleum block carved by Gwen Frostic / THF719495

When World War II redirected the supply of copper that Gwen had been using for her metalwork, she turned to linoleum block printing. Using a press that she disassembled and reassembled to learn how it worked, Gwen began printing commercial letterhead, stationery, and business cards; in between commercial jobs, she sketched her own nature designs and carved them into linoleum blocks. By the war’s end, Gwen was living in the back of her print shop—a set-up that she would continue in for the rest of her life. The business for which she would become most known— Presscraft Papers—had been born.

“Merry Christmas!,” 1955 / THF716787

After the death of her father in 1954, Gwen moved to Frankfort in northern Michigan, setting up a small shop downtown. In addition to selling her nature prints to the summer tourists who came to the scenic bayside town, Gwen developed a mail order trade that exponentially grew her business. In 1957, Gwen wrote her first book, My Michigan. Its style became one that she would use in all her subsequent publications: prose that is almost poetry, printed on thick, deckled paper, alongside charming natural elements printed from Gwen’s linoleum blocks.

For a woman who rarely wanted to talk about herself, her books are perhaps the closest revelation of who Gwen was: an intense thinker, enamored with the natural world around her, with an uncomplicated, pragmatic, yet optimistic view of the world.

On April 26, 1964, Gwen opened the new home of Presscraft Papers: a multi-level store built of trees, rocks, and a sod roof, set amidst a 40-acre swamp property along the Betsie River in Benzonia, Michigan. The main floor of the shop overlooked the print room, where visitors could see the Heidelberg presses that produced the stationery the store sold. On the second floor, carefully concealed from public view, was Gwen’s apartment, featuring two large screened-in porches and floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the property’s pond.

The Heidelberg presses (foreground) and handcarved linoleum blocks (back wall) used to print Gwen’s designs, 2024 / Photo courtesy of Rachel Yerke-Osgood

Despite being tucked in what many would consider to be the middle of nowhere, Gwen’s business thrived. By the 1980s, Presscraft Papers had made Gwen over a million dollars, as visitors flocked from across the state, across the country, and around the world. In addition to her business success, Gwen also received numerous awards and special recognitions. In 1978, May 23 was declared Gwen Frostic Day in Michigan. In 1986, she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame. Rather than resting on her laurels, Gwen continued to create new designs and tend to her business well into her 90s.

In 2001—one day before her 95th birthday—Gwen passed away. Her shop remains, though, little changed from when Gwen herself lived and worked there. Much as the ducks still flock to the pond Gwen loved so much, visitors continue to flock to the store. While many come to shop, others come simply to drink in the tranquility of their surroundings and the charm of Gwen’s designs.

Gwen Frostic Prints, home of Presscraft Papers in Benzonia, Michigan / Photo courtesy of Rachel Yerke-Osgood

This, then, is the legacy that Gwen Frostic carved for herself as she carved her linoleum blocks: a gifted artist, a determined woman, and a devout lover of the natural world.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.

Symbols in Simplicity: The Photography of Margaret Bourke-White

Photojournalism at its best has the power to extend beyond being merely documentary; at its finest, it is intended to make the viewer think or feel something about the subject matter. In the early part of the 20th century, photojournalism saw a new boom, and the field was led by innovative photographers — many of them women — with opinions about the subjects they shot. Among these pioneers was Margaret Bourke-White.

Margaret Bourke-White was born on June 14, 1904, in New York City. Her father, Joseph White, was a factory superintendent and inventor with a mind for machinery; her mother, Minnie Bourke, was a homemaker who firmly believed that Margaret should not be impacted by traditional gender limitations. From a young age, Margaret shared her father's interest in the mechanical, while also longing for a career that would offer adventure and excitement. In 1924, she married photographer Everett Chapman, but the marriage dissolved in 1926. After graduating from Cornell University in 1927, she moved to Cleveland to pursue a career in commercial photography.

Continue Reading