Horse-Drawn Vehicles in the City

| Written by | Bob Casey |

|---|---|

| Published | 9/13/2021 |

Horse-Drawn Vehicles in the City

| Written by | Bob Casey |

|---|---|

| Published | 9/13/2021 |

In the years before automobiles, American cities relied on horses and horse-drawn vehicles to move people, freight, money, and information. In this photograph, taken around 1875, horses pull carriages, buggies, and wagons along a commercial Detroit street. / THF98844

In the years before automobiles, American cities relied on horses and horse-drawn vehicles to move people, freight, money, and information. In this photograph, taken around 1875, horses pull carriages, buggies, and wagons along a commercial Detroit street. / THF98844

American cities in the 18th and 19th centuries, the height of the Carriage Era, were horse- powered. Relatively few individual city dwellers owned horses because the animals were expensive to keep, but freight and passengers moved through cities pulled by horses. By the 1840s, American cities were filled with horse-drawn omnibuses, street railways, stagecoaches, and delivery vehicles. Census data for the 19th century did not include horses, but as late as 1900, Manhattan had 130,000 horses; Chicago, 74,000; Philadelphia, 51,000; and St. Louis, 32,000.

The Impact of Urban Horses

The life of horses in the cities was not pleasant. One traffic analyst estimated that a city horse would fall on average every 96 miles it traveled. In the 1880s, the New York City Sanitation Department was removing 15,000 dead horses from the street each year. Living horses deposited between 800,000 and 1,300,000 pounds of manure each day, along with thousands of gallons of urine. The filth made city streets unpleasant and unhealthful.

Dead horses, like this one in New York City in the first decade of the 20th century, were not uncommon on urban streets during the Carriage Era. / THF100882

Disease was also a problem for the horses. In 1872, a flu-like epidemic swept through northern cities, killing horses by the thousands and bringing commerce to a virtual standstill. The conditions led to the creation of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), led by the crusading Henry Bergh.

A perhaps surprising result of the importance of horses in urban life is that cities, not farms, gave rise to modern veterinary medicine. In 1850, only 46 Americans called themselves veterinarians, but 26 of those lived in New York City. Most of these individuals were not trained in schools but were folk practitioners who relied on traditional methods. A series of equine epidemics during and after the Civil War that swept through crowded urban stables spurred efforts to improve veterinary knowledge. The American Veterinary College, affiliated with Columbia University, was the first scientific veterinary school in the United States. Veterinarians adopted Louis Pasteur’s new germ theory of disease more quickly than did doctors who practiced on humans. By 1890, there were 6,954 veterinarians, almost all located in big cities.

In the end, the combination of electric streetcars and gasoline-powered motor vehicles drove the majority of horses from cities.

Transporting People

Residents of New York’s Fifth Avenue opposed streetcar lines, claiming the vehicles were too quick and quiet to safely share the street with pedestrians and horse-drawn traffic. As an alternative, the Fifth Avenue Coach Company ran omnibuses like this one, pictured circa 1900–1906. / THF203322

Horse-drawn omnibuses were the first great public conveyances in American cities. The first omnibus was used in New York in 1831, and within a few years, omnibuses had been adopted in Philadelphia, Boston, and other cities. Omnibuses were generally highly decorated to make them visible to potential riders. They were functional, but the rough nature of city streets made them hard on both horses and passengers. A contemporary observer in the New York Herald noted that “modern martyrdom may be succinctly described as riding in a New York omnibus.”

The great improvement over the omnibus was the horse railway. Iron wheels on iron rails provided an easier pull for the horse and a smoother ride for the passengers. Again, New York led the way in 1832, and by the 1850s, horsecars had spread to Boston and other cities. Horse-powered railways helped reshape American cities, allowing people to move farther from their place of work, which then facilitated the growth of suburbs. As city centers gradually emptied of residences, they became devoted to business. The modern pattern of separate business and residential neighborhoods can be traced to the horse railway.

Alternatives to the crowded omnibuses and horsecars were the ancestors of today’s taxicabs—four-wheeled vehicles called hacks and two-wheeled vehicles called cabs. New York issued its first hack license in 1692. Though more expensive than omnibuses and horsecars, hacks and cabs offered greater convenience and privacy for those who could afford the ride.

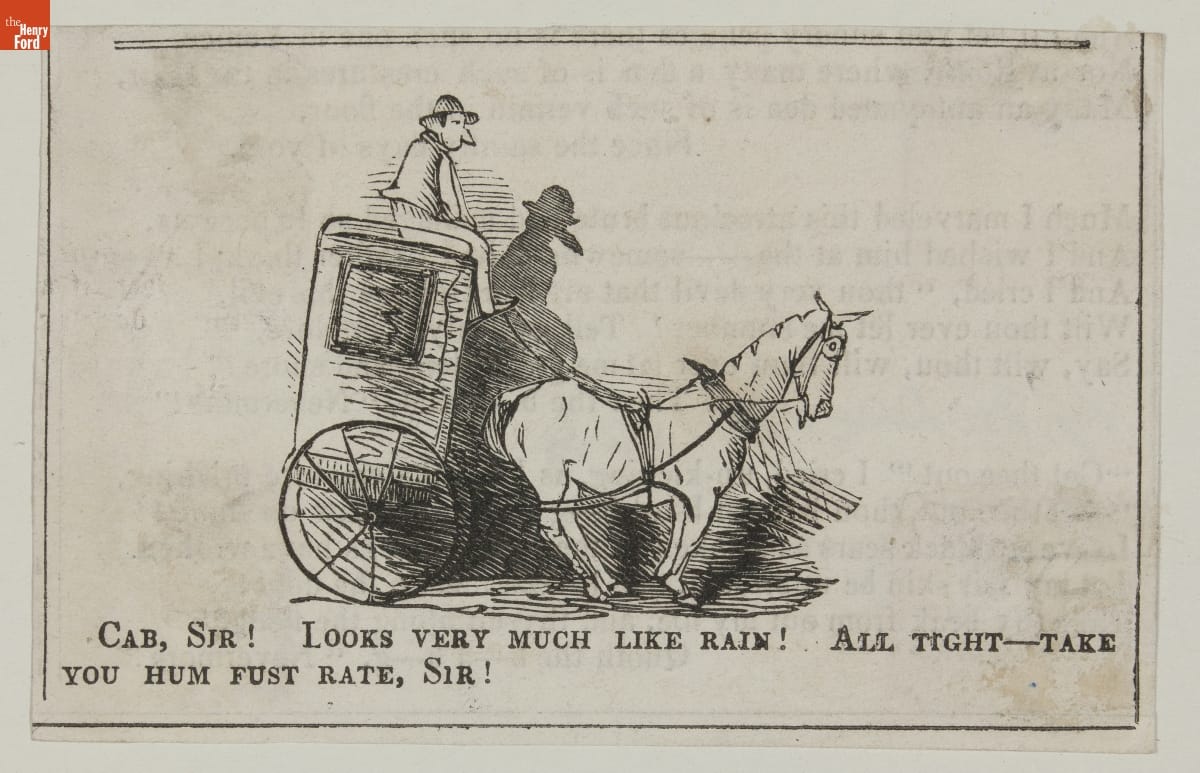

A taxicab driver petitions a would-be customer by pointing to the threat of rain in this cartoon from 1846. Light, two-wheel hansom cabs, like the one in this illustration, emerged in the 1830s. / THF204288

Because of the cost of keeping horses, ownership of private vehicles was not widespread. However, wealthy city dwellers could afford both the horses and the coaches, and vied with one another for the most stylish, fashionable “turnouts.” But most citizens, if they wished to drive a vehicle themselves, resorted to livery stables, where horses and simple buggies or gigs could be rented.

Delivering Goods

One-horse delivery wagons were common on American streets from the late 19th century into the 20th. While all delivery wagons shared the same basic layout, more refined versions featured wood panels instead of duck cloth around the cargo area, or wood panels with glass alongside the driver's seat. This circa 1908–1912 wagon from our collection was used by the J.A. Peters company, a meat retailer and wholesaler in Detroit. / THF188029

All manner of goods had to be moved into, out of, and within cities. Coal, oil, beer, hay, milk, machinery—the list is endless. The vehicles that moved these goods probably constituted the majority of vehicles in the urban traffic mix. In large cities, department stores owned sizable fleets of vehicles and herds of horses in order to meet the demand for home delivery of purchases. For example, in 1875, Chicago’s Marshall Field’s department store owned 50 wagons and 100 horses. Delivery vehicles were often especially well turned out, so as to reflect well on the owners. No customer of Marshall Field’s wanted a grubby van pulled by a broken-down horse showing up to drop off a fashionable dress or piece of furniture.

Fighting Fires

Cole Brothers produced about 60 horse-drawn steam fire engines in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, from 1867 to 1880. Simple and rugged, this example from our collections could pump about 550 to 600 gallons of water per minute. / THF188103

One of the smallest, but most romantic, groups of horse-drawn city vehicles was fire-fighting vehicles. The earliest fire vehicles were pulled by the volunteer firemen themselves, who also supplied the manpower to operate the pumps. When much heavier steam-powered fire pumps were developed, they required horses to pull them. Special harnesses were developed for firehouse use that could be quickly installed on the horses, allowing fire vehicles to leave the station within 20 seconds of receiving the alarm. Fire horses were among the best cared-for horses in the city.

More Horse-Drawn City Vehicle Highlights from The Henry Ford’s Collection

Jones Horse-Drawn Streetcar, circa 1875

THF91049

The horse railway is an American innovation. Its distinctive appearance is rooted in practical considerations. The inward curve of the lower sides allows the use of shorter, and therefore lighter, axles. The spoked wheels are also lighter than solid wheels. The raised clerestory roof is raised only over the center of the car, not where passengers sit along the side. This lowers the weight of the car, so the horse pulls more paying passengers and less dead weight. The clerestory is lit with colored glass, and the endpoints of the car’s route are clearly painted, for the benefit of potential riders. This car is a small one, intended to carry only 15 passengers and to be pulled by a single horse. It was used by the Brooklyn City Railroad between 1881 and 1897. In 1892, the railroad had 142 horse-drawn cars serviced by 5,500 horses.

Chariot Made by William Ross for Angelica Campbell, 1792–1802

THF90762

One of a handful of 18th-century American carriages that have survived unrestored, this is a magnificent example of a vehicle intended for showing off. Chariots were closed vehicles that held only two people and were driven by coachmen. This one was built for Angelica Bratt Campbell, whose husband, Daniel, was one of the richest men in New York state. It features silver-plated trim, rich carvings, stylish C-spring suspension, and an interior trimmed in leather, baize, coach lace, and silk. It should be noted that the C-springs, while visually quite striking, actually put more load on the horse when putting the chariot in motion from a standing start. Two horses pulled this chariot.

Landau, Made for Abram and Sarah Hewitt of New York, 1890

THF87336

Over 90 years newer than Angelica Campbell’s chariot, this landau reflects changes in taste, style, and methods of manufacture. Its lines are sharper and squarer, but the wheels and undercarriage are also lighter than those of the chariot. Its beauty depends more on its well-drafted shape than on applied ornament. Even though the landau is a very expensive vehicle, it was built utilizing powered machinery and many standard parts, rather than handmade like the chariot.

The landau was made by Brewster & Company of Broome Street, New York City, perhaps the most famous of American carriage makers. James Brewster established a small carriage shop in 1804 and taught the trade to his sons Henry and James B. The brothers each set up their own company, but James’s business faltered in the late 1890s. Brewster & Company of Broome Street was Henry’s enterprise, and it survived into the 20th century under the leadership of his son William. This Brewster landau was owned by wealthy industrialist and mayor of New York Abram Hewitt.

Veterinary Ambulance, circa 1900

THF133557

Wealthy New Yorker Henry Bergh was appalled at the often cruel, callous treatment of horses, which were often merely considered a means of turning food into money. Inspired by anti-cruelty groups in London and Paris, Bergh founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in 1866. The organization aimed to speak for all animals, but its focus was initially on horses. It successfully lobbied for anti-cruelty laws, and Bergh himself often chastised teamsters who mistreated horses, sometimes making a citizen’s arrest.

Bergh also designed an ambulance for hauling injured horses or for removing dead ones. It featured a movable floor that could be cranked out and slid underneath a downed horse. The ambulance was eventually adopted by other anti-cruelty organizations and veterinarians. This one was used by Detroit veterinarian Dr. Elijah E. Patterson, who practiced from 1890 to 1940. It is set up to be pulled by two (healthy) horses.

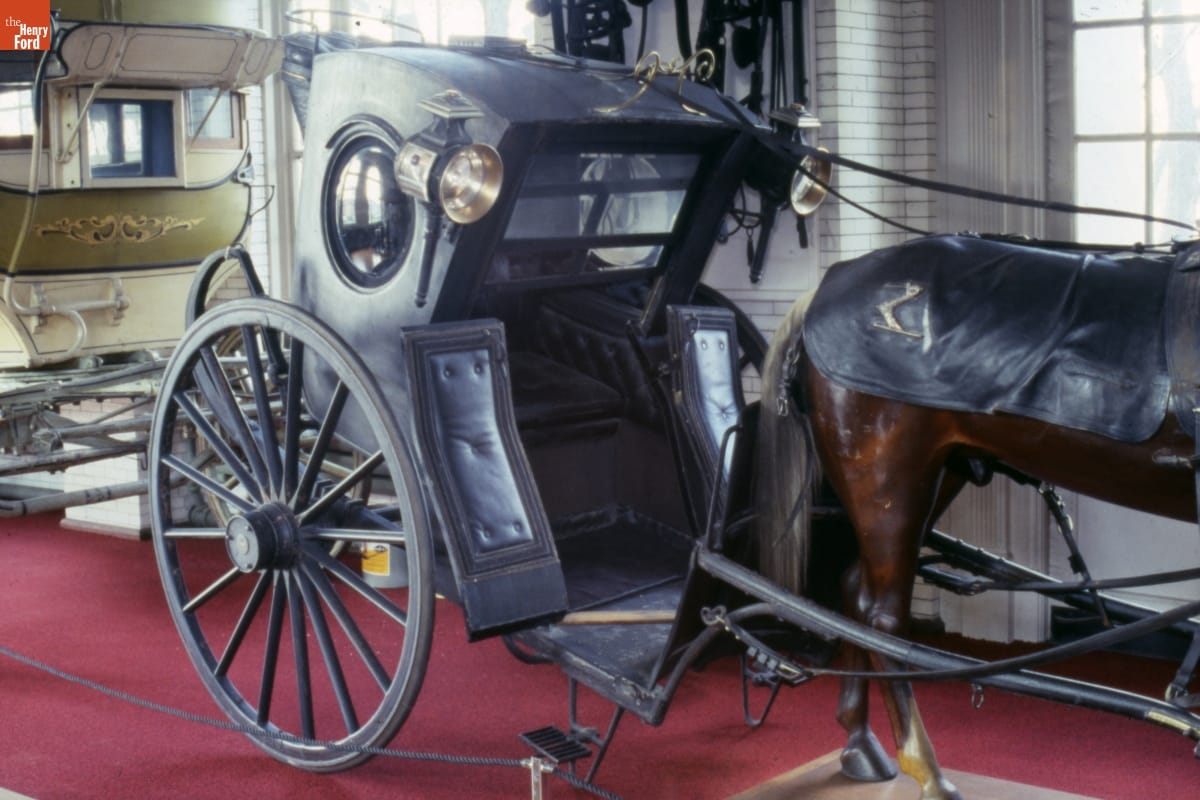

Joseph Thatcher Torrence's Hansom Cab, 1880–1890

THF74930

The two-wheeled hansom cab was developed in England in the 1830s but was not adopted in American cities until the 1880s. Having only two wheels allowed the vehicle to be pulled by only one horse. The driver sat outside, perched above the back of the cab, giving him an excellent view of the street and of any potential customers at the curb. Although named after its originator, a Mr. Hansom, the cab is also a “handsome” vehicle, with C-springs, round windows, and large carriage lights. People occasionally also purchased hansom cabs for private use. Chicago industrialist Joseph Thatcher Torrence owned this example.

Beer Wagon, circa 1900

THF188026

Brewers used vehicles like this one to deliver kegs of beer to taverns. The wagon is heavily constructed to bear the weight of the kegs. The brewer fully utilized what little space is on the wagon for advertising. At the rear of the vehicle is a half-round metal back with a 10-pointed star, painted in yellow and black on a blue ground with yellow and black trim. The undercarriage is red with black and yellow striping. At least two horses, perhaps four, pulled this heavy wagon. They would have been carefully matched and outfitted so as to give any observers the best possible impression of the brewery.

Hearse, circa 1875

THF80580

This hearse was designed to carry the deceased to the cemetery in dignity and style. It features large oval glass sides through which the casket could be seen, along with curved glass doors at the rear. It has a pair of large, silver-plated lamps at the front and other silver trim inside. Two horses drew this hearse.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Transportation: Past, Present, and Future—From the Curators.”

Keywords | |

|---|---|

Themes |