The Search for Home

Detroit Reacts to the Great Migration: Before the first World War, a majority of Detroit's African American population lived on the East Side and shared the area, known as Black Bottom, with white immigrant populations. At this time, relatively few African Americans, just 1.2% of the total population, called Detroit home. By 1930, the city’s African American population had grown by over 1,991%. The white immigrant population began to vacate the Black Bottom area and were quickly replaced with the growing population of African Americans attracted to the north by the promise of employment in Detroit’s booming auto industry and an escape from the rampant oppression of the south. As the African American population in Detroit increased, racial residential boundaries began to form, due in part to the stress on housing stock, as well as to outright discrimination in institutions such as employment and real estate.

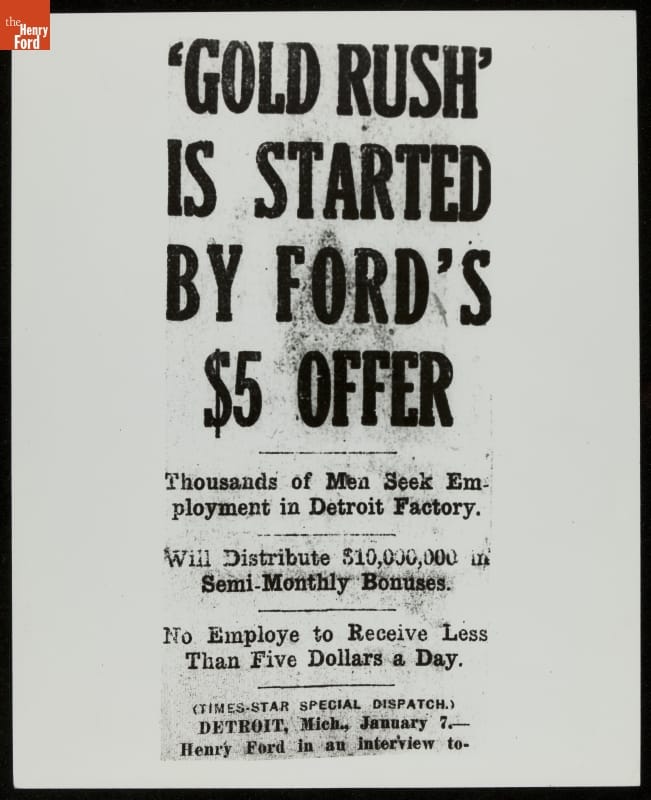

Photographic print - "Newspaper Article, "Gold Rush is Started by Ford's $5 Offer," January 7, 1914" - Ford Motor Company

The automobile industry and Henry Ford’s highly-publicized $5-a-day helped to draw people in great numbers to the Detroit area. However, for African American workers, reality often differed from their hopes and expectations in the north. While many of the automotive manufacturers did hire African Americans, it was almost always for the lowest paying jobs, such as in the janitorial department or the foundry. Ford Motor Company led the automotive industry in its hiring of African American workers by 1919. The company paid African American workers the same rate as their white counterparts and hired for a variety of positions, including skilled labor. Across the board, however, African American workers made less money than their white counterparts, and consequently, had less income for quality housing.

Photographic print - "Pickling Metal Crankcases and Other Parts to Remove Surface Impurities, Ford Rouge Plant, 1936" - Ford Motor Company Photographic Department

Discriminatory real estate practices played a significant role in the housing issues which plagued Detroit. Racially restrictive covenants, which legally ensured the sale of property to only white buyers, became increasingly common in Detroit. Even if a restrictive covenant was not in place, the Detroit Real Estate Board warned area realtors “not to sell to Negroes in a 100 percent white area,” thereby enforcing and perpetuating Detroit’s racial geography. Further, the practice of “redlining,” or the racial categorization of areas by their perceived financial risk in home insurance and mortgage lending, effectively shut out black homebuyers from the market. The practice extended to the lending of new mortgages, but also to home loans, leading to the inability to complete home repairs and, eventually, an abundance of blighted homes in black neighborhoods. In addition, real estate agents erroneously reported to white homeowners that the presence of black families in their neighborhoods would lower their property values. White homeowners, even those without ingrained prejudices against African Americans, certainly did not want their property values to lower, so rallied against any attempt by an African American homebuyer purchasing in their neighborhoods. The infamous story of African American Physician Dr. Ossian Sweet exemplifies the discrimination and mob violence experienced by those who attempted to move into white neighborhoods.

Discrimination in the workplace meant that African Americans, as a whole, made significantly less money than their white counterparts. Redlining practices forced them into racially-segregated neighborhoods and cemented their inability to access loans for mortgages or home repairs. Yet, the promise of the north continued to draw African Americans to Detroit. Without access to capital, increasingly-crowded neighborhoods became increasingly-deteriorated. At each turn, discriminatory systems excluded an entire population from quality housing. From these conditions, Charles H. Lawrence and his family departed Detroit in search of quality housing and a better life. He became the first African American to settle in Inkster, Michigan, and hundreds soon followed.

African Americans Settle in Inkster

The City of Inkster, also located in Wayne County, is approximately fourteen miles from downtown Detroit. Detroit Urban League President John Dancy fielded many housing inquiries from frustrated African American migrants to Detroit in the post-World War I period and beyond. Unable to locate sufficient housing in the City of Detroit, Dancy broadened his search outside the City with hopes that more rural areas would not have the same restrictive covenants and that lesser demand would persuade landowners to sell to African American buyers. In 1920, Dancy succeeded when he found amenable property owners in possession of 140 acres in rural Inkster. Although Inkster’s first African American residents’ settlement in Inkster preceded Dancy’s discovery, the 140 acres of available land enabled and impelled hundreds more African American families to move from Detroit to Inkster, despite the lack of a local government or basic public amenities like streetlights or sewer lines.

Clipping (Information artifact) - ""Henry Ford on Unemployment," 1932" - Detroit Free Press (Firm)

A Community Becomes a Project

Henry Ford was vocal about his disdain for institutionalized philanthropy. He wrote an entire chapter, entitled “Why Charity?” in an autobiography, and explained, “philanthropy, no matter how noble its motive, does not make for self-reliance…A philanthropy that spends its time and money in helping the world to do more for itself is far better than the sort which merely gives and thus encourages idleness.” Henry Ford’s brand of philanthropy was characterized by helping people help themselves. During the Great Depression, Henry Ford was called upon by the City of Detroit to provide aid because the City’s welfare offices were overwhelmed. Their argument, aside from civic responsibility, was that the City was not receiving taxes from Ford Motor Company (FMC’s factories were located outside Detroit) yet as many as “36 percent of the families receiving care from the City of Detroit were former Ford employees” in 1931. The public goodwill that Ford’s $5 a day policy brought was quickly dissipating. In 1931, Ford agreed to two philanthropic ventures; he provided a low-interest, short-term $5 million loan to the City of Detroit and essentially took the then-Village of Inkster under the Ford Motor Company’s auspices.

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

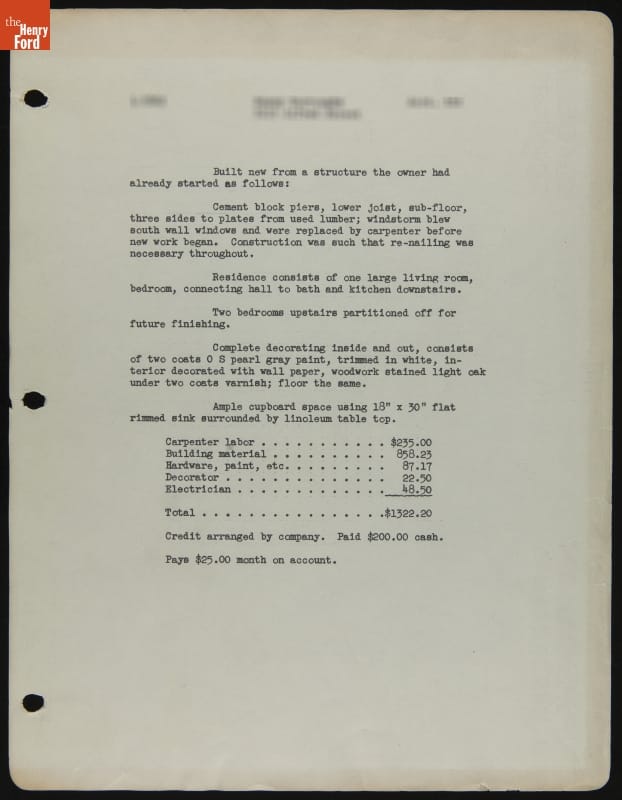

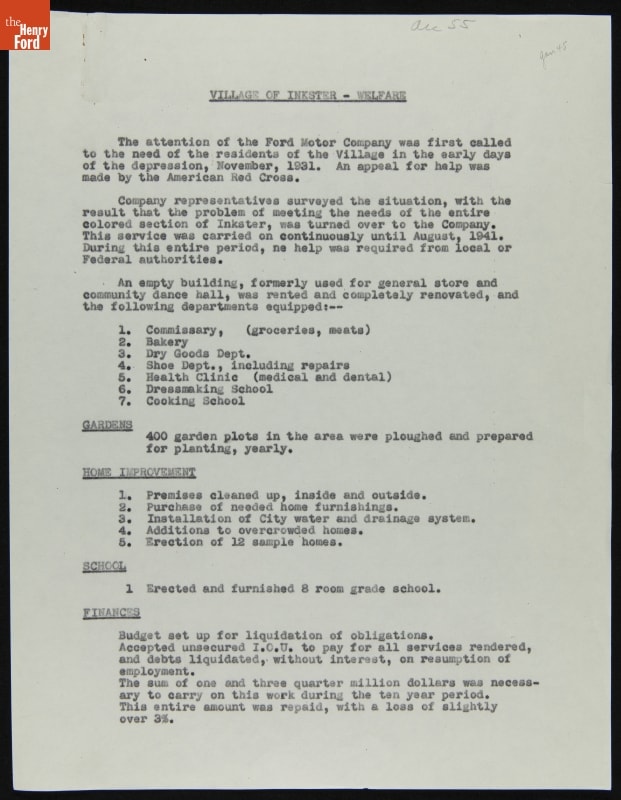

Report - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

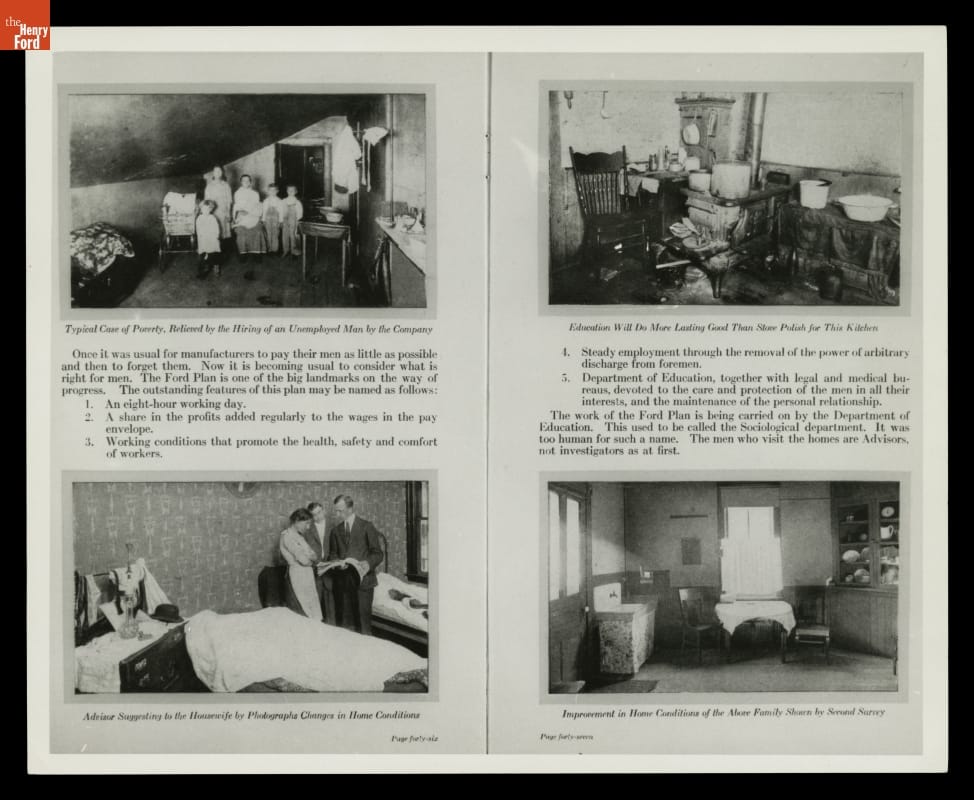

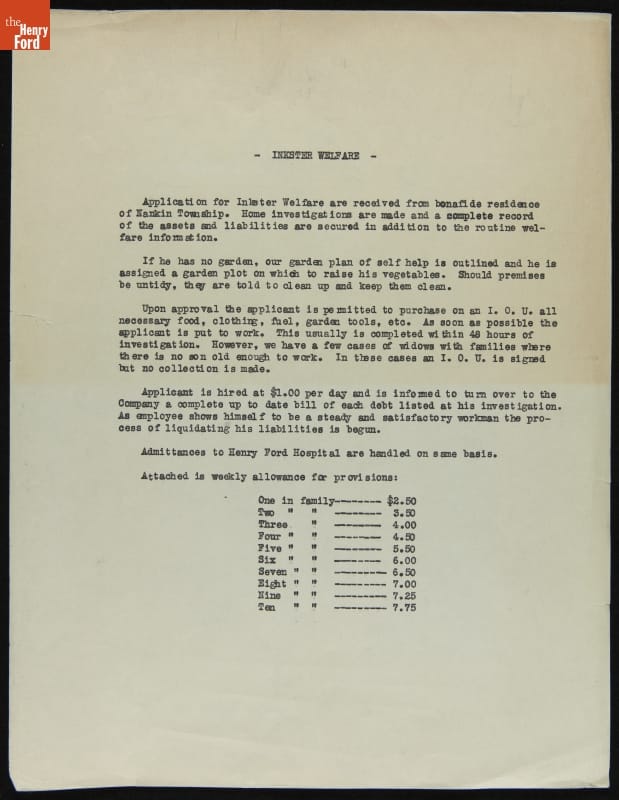

By 1931, a few years into the Great Depression’s hardships, the residents of Inkster were struggling. Unemployment and debt were high, public services had been cut, and many residences remained partially-completed, as the Great Depression halted progress in the young village. Controversially, Henry Ford placed FMC’s Sociological Department in charge of what became known as the Inkster Project. The Sociological Department was created in 1914 in order to manage the diverse workforce and ensure employee adherence to the company’s strict standards, which were paternalistic in nature and often crossed the home life-work life boundary. In Inkster, the Sociological Department immediately began implementing programs to comprehensively rehabilitate the village. A commissary, which sold high-quality, low-cost food and essential home goods, was established. Coal was distributed to those who needed it to heat their homes. Debtors were paid off, and a medical clinic and school were constructed. Homes deemed insufficient were rehabilitated. The inability to pay for these services was irrelevant; a type of “I.O.U,” repayable through Ford-provided work and wages, was enough to access all life’s necessities.

Photographic print - "Checking on Ford Employees Home Conditions, Views from "Factory Facts From Ford," 1917"

The Legacy of the Inkster Project

Although the Inkster Project was generally highly-regarded at the time, the FMC Sociological Department’s role was often overreaching. When agreeing to Ford’s aid, an Inkster resident was also agreeing to running their household as preferred by Henry Ford. Although his funds undoubtedly helped Inkster during the Great Depression, Ford’s motives were not entirely altruistic. Besides the much-needed public relations boost he received from the Inkster Project, he also was able to assert his influence and ideals on a community that largely had no choice but to accept his aid -- with all strings attached.

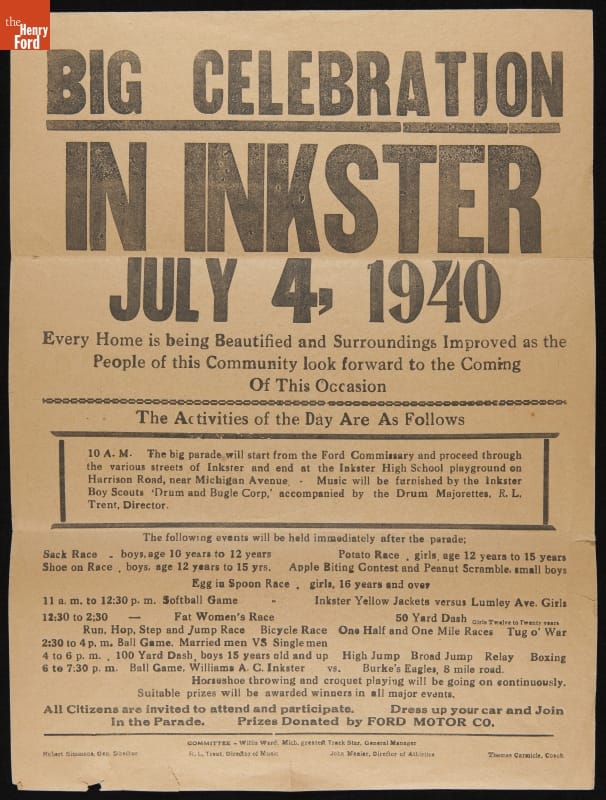

Broadside (Notice) - "Big Celebration in Inkster," July 4, 1940"

The Inkster Project’s legacy is complicated; many historians criticize Henry Ford’s paternalistic nature and the perhaps forceful imposition of his will onto the desperate, but others, including former residents of Inkster, praise Henry Ford for his aid. In her reminiscences, Georgia Ruth McKay explains that Inkster became a “jungle village changed into a city” during this period and that, “without his [Henry Ford’s] help, many would not have survived.” The Inkster Project was slowly phased out, but continued to operate in Inkster until 1941 when all programs were withdrawn.

Progress report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Report, 1931-1941" - Ford Motor Company

Report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Provision Report, circa 1936" - Ford Motor Company

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. In writing this piece, she appreciated the research and writings of Beth Tompkins Bates’ “The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford”, Thomas J. Sugrue’s “The Origins of the Urban Crisis; Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit,”, and Howard O’Dell Lindsey’s dissertation, “Fields to Fords, Feds to Franchise: African American Empowerment in Inkster, Michigan.”

20th century, Michigan, labor relations, home life, Henry Ford, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Katherine White, African American history

Facebook Comments