Civilian Conservation Corps

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 9/20/2021 |

Civilian Conservation Corps

| Written by | Debra A. Reid |

|---|---|

| Published | 9/20/2021 |

Civilian Conservation Corps Company No. 1614, 1934. / THF293207

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began during an economic crisis unmatched in U.S. history. One out of four Americans was out of work in March 1933 as consumer demand reached an all-time low. Congress authorized the CCC to put some of these unemployed men to work. The U.S. War Department oversaw the program, building camps and undertaking projects in all 48 United States, plus Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Enlistment peaked during September 1935 when 505,782 enrollees worked in 2,652 camps. Overall, between 1933 and 1942, approximately 5% of the U.S. male population, around 3 million men, participated in the CCC.

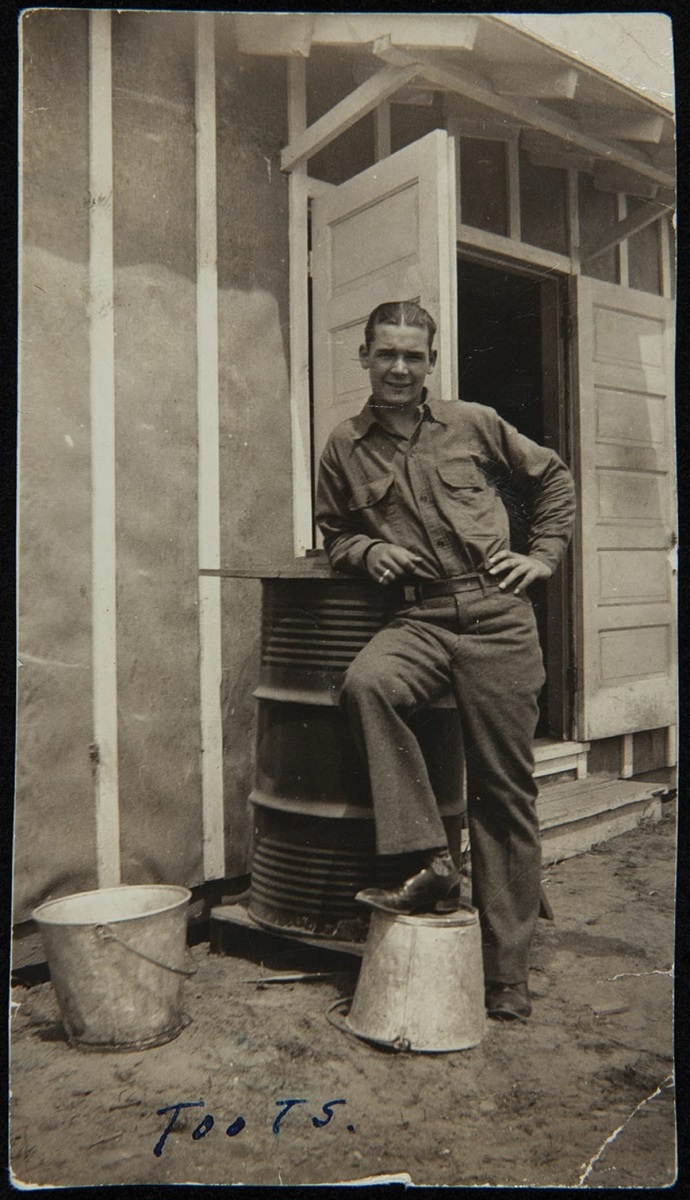

Stanley J. Zaleski at 1614th Co., Civilian Conservation Corps, Camp McComb, Munising, Michigan, April–September 1934. / THF274652

Franklin D. Roosevelt emphasized the quantity and quality of CCC work in his re-election campaign booklet, “This Generation Has a Rendezvous with Destiny” (1936). Between its launch in March 1933 and 1936, the CCC had erected 4,200 miles of new telephone lines, cut nearly 47,000 miles of new fire breaks, and cleared 64,000 miles of new truck trails. In cooperation with the Tennessee Valley Authority, its members had constructed over 200,000 stone and stone-and-log dams in that area. Members also engaged in extensive educational activity with 71% of enlistees taking part, including 90,000 attending elementary classes and 212,000 enrolling in special courses (pg. 12).

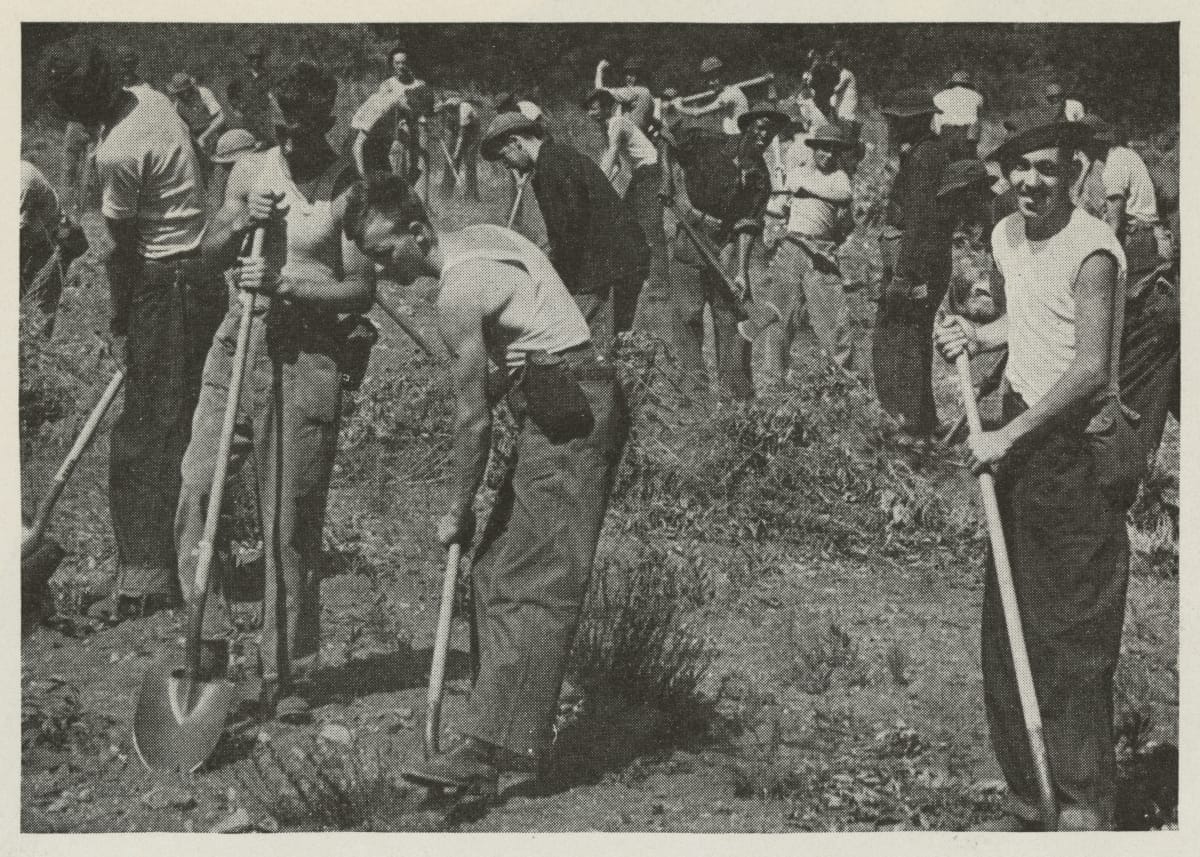

This detail from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s campaign booklet, “This Generation Has a Rendezvous with Destiny,” 1936, featured Black and white enlistees at work. / THF132716

The legislation that created the Civilian Conservation Corps prohibited discrimination based on “race, color, or creed.” Promotional material such as the photograph (shown above) of CCC work in Roosevelt’s 1936 campaign booklet illustrated integration. Yet, implementation often appeased anti-integrationists and perpetuated the separate-but-unequal doctrine of the U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v Ferguson (1896).

We must also acknowledge that CCC work occurred on lands formerly occupied by indigenous people. Each CCC camp site and CCC project represents an opportunity to remember those who previously occupied the place.

A separate Indian Emergency Conservation Work program began in 1933 in response to requests from Bureau of Indian Affairs administrators and sovereign Indian nations. It was renamed the Civilian Conservation Corps—Indian Division (CCC-ID) in 1937. It undertook work on federally recognized reservations and emphasized land preservation, soil conservation, forest restoration, and sustainable ranching practices, among other projects. Within six months, the CCC-ID had camps on 33 reservations in 28 states. As many as 85,000 men worked on CCC-ID projects. Its success laid the groundwork for a larger “Indian New Deal,” authorized in 1934 with the Indian Reorganization Act.

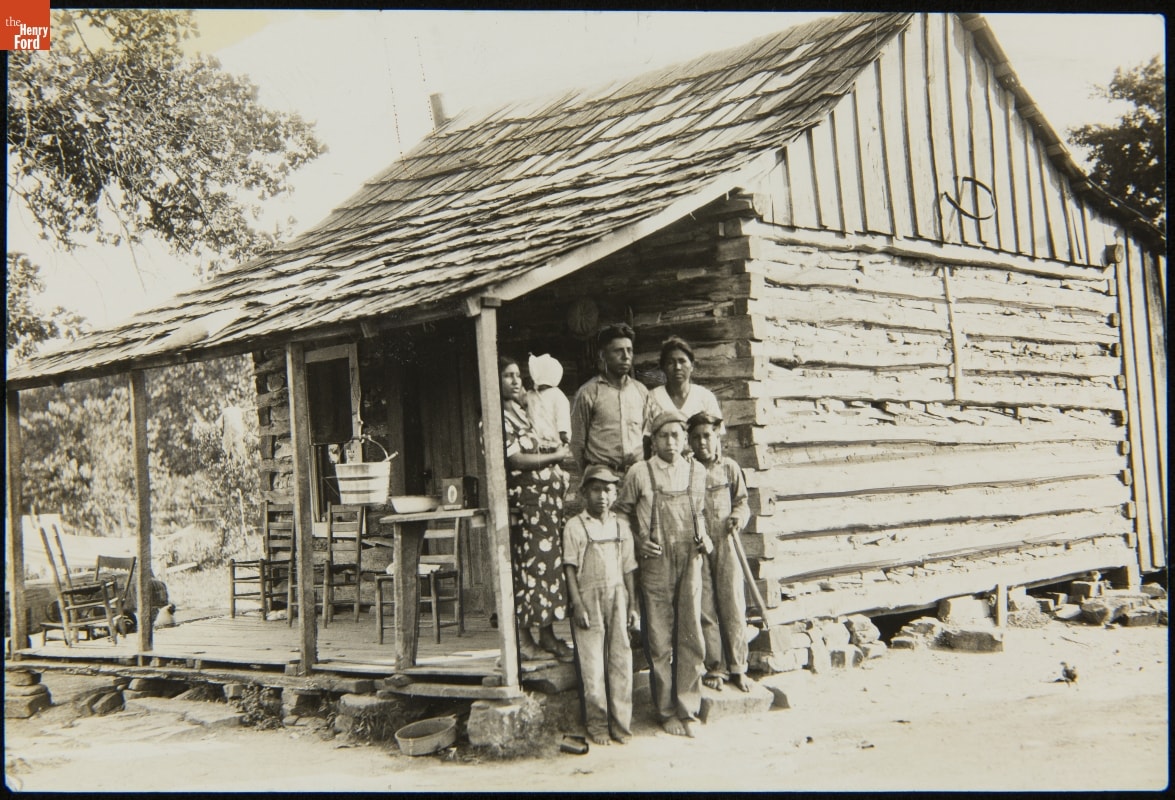

Indian Relief Project, McCurtain, Oklahoma, June 18, 1934. / THF290170

The CCC-ID’s worker policies differed in significant ways from the CCC’s policies toward Black and white men. This reflected its autonomy as a division of the Bureau of Land Management and not of the U.S. War Department, and the independence of separate indigenous nations negotiating their own CCC structures that supported families in different ways. For example, married men could enlist in the CCC-ID and live at home, receiving as much as $42 per month for work (including a stipend otherwise spent by camps on housing and feeding enlistees). In contrast, Black and white CCC enlistees, all single, earned $30 per month. They retained only $5 while the remaining $25 went home to their parents or extended families.

All CCC enlistees, regardless of race, color, or creed, worked hard and in all kinds of weather.

Man standing outside a Civilian Conservation Corps barracks in winter, circa 1935. / THF620731

Their rest came on cots in barracks with tar-paper walls.

Interior of Civilian Conservation Corps barracks, 1934. / THF620729

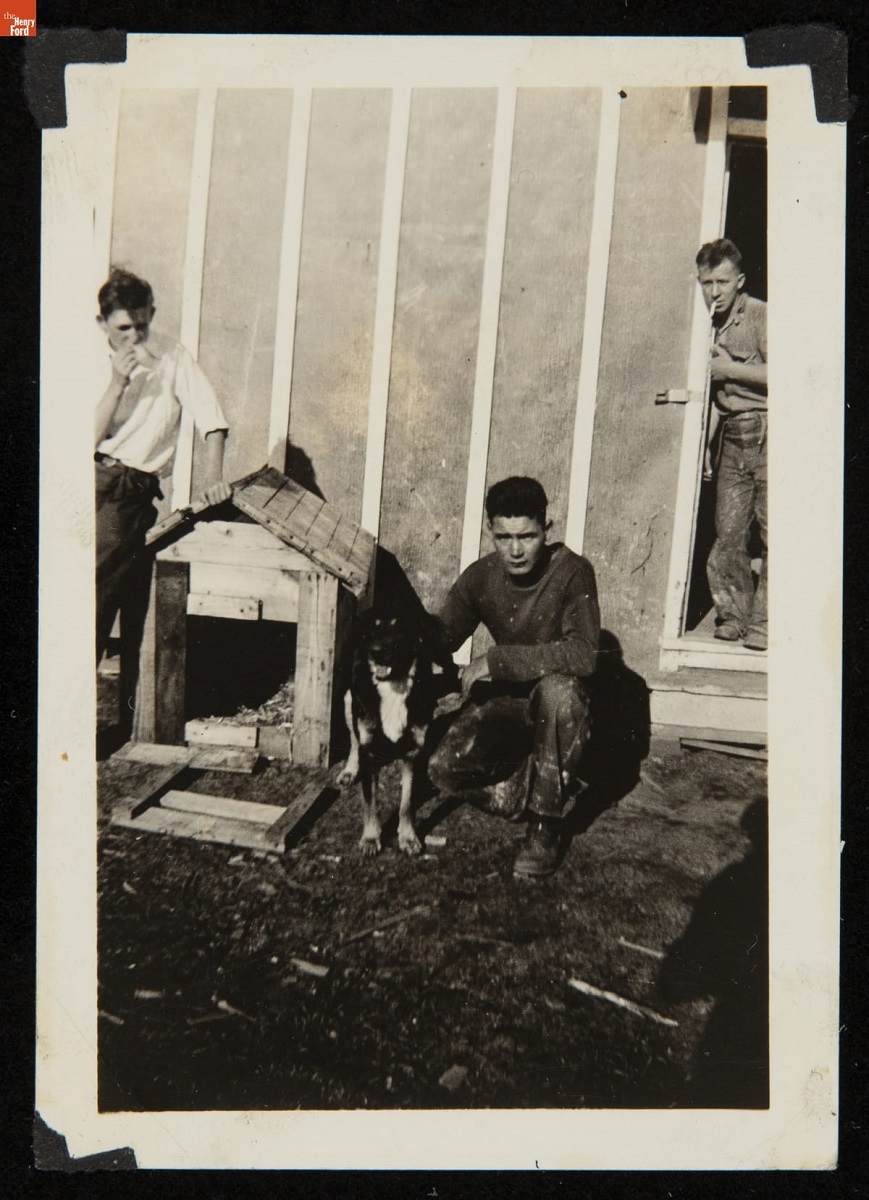

Work schedules allowed some time for recreation, but even then, the company dog warranted attention.

Stanley Zaleski and a dog outside Civilian Conservation Corps Barracks, 1934. / THF620737

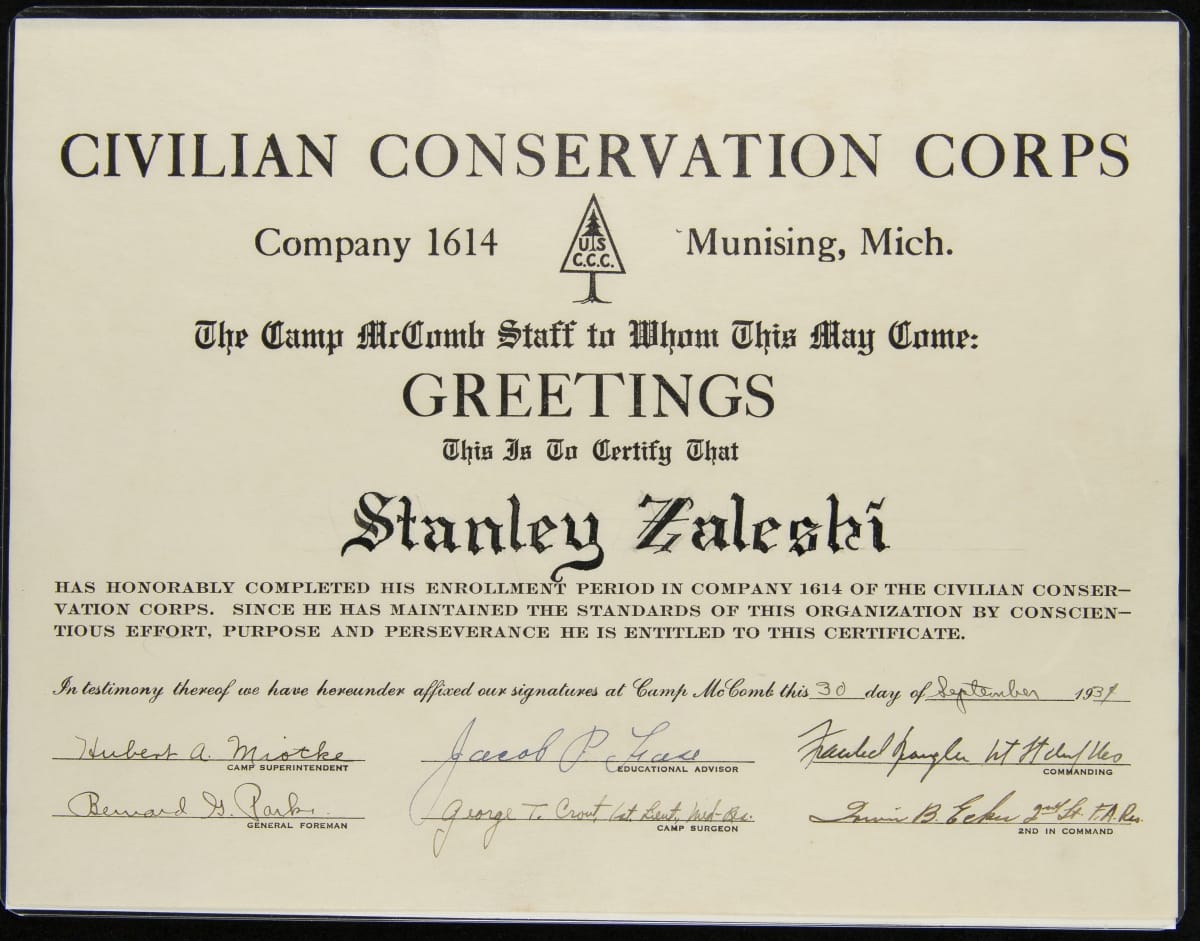

The CCC followed strict protocols, including formal enlistment and discharge procedures and paperwork.

Civilian Conservation Corps Company 1614 completion certificate, September 30, 1934. Stanley “Toots” Zaleski’s Discharge Certificate confirmed the reason for his discharge as “expiration of term of enrollment for convenience of the U.S.” / THF293211

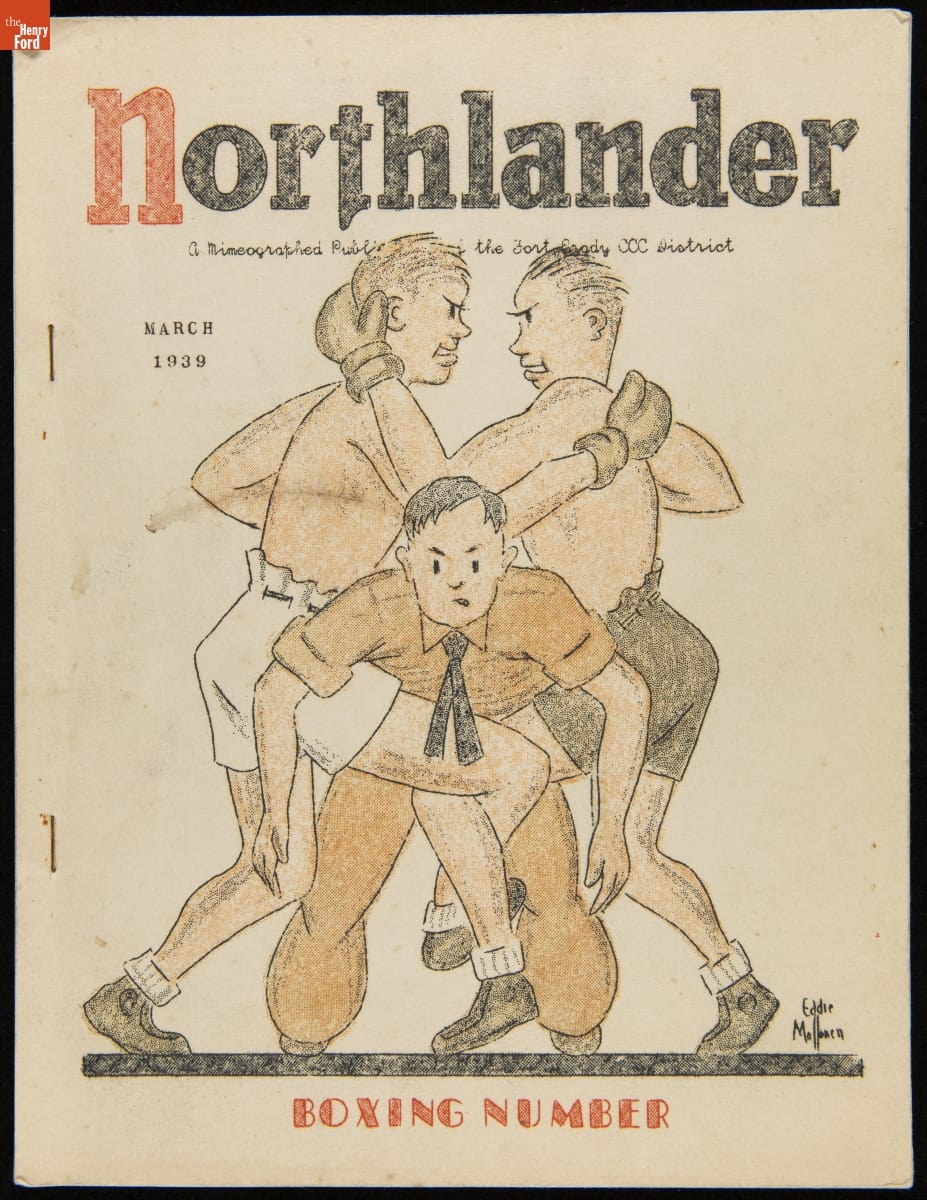

Communication took the form of monthly newsletters produced by enlistees in camps and in CCC regions. CCC camps held as many as 200 Black or white enlistees while CCC-ID projects incorporated 30–40 enlistees at a time. The newsletters represented a proactive effort to create a community identity. Sporting events and other organized leisure activities also helped generate collegiality.

The Northlander: A Mimeographed Publication of the Fort Brady CCC District, March 1939. / THF624987

Pennants helped convey the identity and camp purpose, much as pennants symbolized allegiance to schools. Some pennants conveyed standard CCC imagery. The lone pine tree symbol appeared on pennants of companies doing work in national forests and others working in state parks. Colors varied as well, even as the logo remained the same. Other pennants emphasized camp features, including barracks. Some carried additional artistic expressions.

Civilian Conservation Corps “1614th Co.” pennant, 1934. This company started in June 1933 near McComb and Munising, Michigan, and worked in the national forest. / THF293213

Pennant, Civilian Conservation Corps Company 1712. This company started in October 1934 and worked near Kaiser and Bagnall, Missouri, likely on Lake of the Ozarks State Park projects. / THF238732

Pennant, Civilian Conservation Corps Company 3745. This company worked near Columbia, Missouri, starting in September 1940, on Soil Conservation Service projects. / THF238734

Pennant, Civilian Conservation Corps, with no company number designated, but featuring illustrations of a typical CCC camp, 1933–1942. / THF238736

Civilian Conservation Corps "Co. 713, Camp Jeanette" pennant, 1936–1941. Camp 713 undertook Soil Conservation Service work near Lake Jeanette in Superior National Forest, near Lake City, Minnesota, starting January 16, 1936. / THF188542

Other souvenirs included sweetheart pillows, designed to remind loved ones back home of their son, brother, betrothed, or friend at work in a CCC camp.

Civilian Conservation Corps sweetheart pillow cover, 1938–1940. Camp 4603 worked on revitalizing grazing land near Harper, Oregon, starting in July 1938. / THF188543

The Civilian Conservation Corps never officially ceased to exist. Bipartisan support sustained the work through 1940 and 1941, even as potential enlistees pursued different opportunities and obligations. The U.S. Congress authorized the Selective Training and Service Act in September 1940, the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. Veterans of the CCC often chose enlistment in their preferred branch of the military over conscription into military service. After the United States entered World War II, Congress closed remaining CCC camps, discharged personnel, and disposed of camp assets (including non-issued clothing) to the U.S. Army.

Today, private-public partnerships sustain CCC work in various ways. Organizations such as Conservation Legacy provide service opportunities to youth, young adults, and veterans, in partnership with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forestry Service, and AmeriCorps. The Veterans Fire Corps helps veterans transition to civilian life while earning Firefighter Type 2 training. Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps engages Indigenous youth and young adults in conservation work that links ecological work with cultural heritage.

The legacy of the CCC remains all around us, but is not always obvious. We travel on roadways that CCC workers helped survey and build. We stop at roadside overlooks and stay in guest lodges that CCC workers built in state and national parks across the country. They also built dams and fire look-out towers, planted trees, improved grazing lands, and restocked lakes—among many other projects. Their signatures remain on the landscape in all these ways, preserving their history while inspiring current conservation work.

Sources:

Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy. This website includes a state-by-state listing of camps and projects. http://www.ccclegacy.org/home.php.

Lacy, Leslie Alexander. The Soil Soldiers: The Civilian Conservation Corps in the Great Depression. Radnor, PA: Chilton Book Company, 1976.

Maher, Neil M. Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Roosevelt’s Tree Army: The Civilian Conservation Corps, virtual exhibit available through the Digital Public Library of America at https://dp.la/exhibitions/civilian-conservation-corps/history-ccc (accessed September 14, 2021).

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture & the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Keywords |

|---|