The WASP: “An Airplane Knows No Sex”

During World War II, a groundbreaking group of American women defied expectations and gender bias to apply their skill in the air, flying over 60 million miles and 12,650 ferrying missions for their country during the war. Nearly 1,100 women volunteered as pilots with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). As WASP Bernice “Bee” Haydu said in a 2013 oral history interview for The National WWII Museum, “We showed the world that an airplane knows no sex.” Yet while they flew military aircraft for military purposes and risked their lives in doing so, they remained classified as civilian aviators and as such they received no military status, benefits, or recognition until decades later.

Even prior to the United States' entry into war, two pioneering pilots Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love were pushing for opportunities for American women in military aviation. They lobbied for inclusion and were bolstered by successful efforts abroad, where women were flying in support of the European Allies. Cochran and Love submitted independent proposals to the Army Air Forces for the noncombat employment of women. As a result, the two women were granted leadership of two programs — the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron led by Love and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment directed by Cochran. The momentum to use women pilots had some powerful advocates. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about the subject in her September 1, 1942, "My Day" column: “We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.” In August 1943, a year after the inception of the two, they were merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots under Cochran with Love in an executive role.

The WASP program took off. Trainees were based at Avenger Field near the small town of Sweetwater, Texas. A love of flying drew fierce competition for limited spots. Training on military aircraft was rigorous and difficult even for the experienced pilots accepted into the program. Unlike male fliers, who learned to fly as part of their training, the WASP trainees entered their program knowing how to fly. They were required to have completed 200 to 500 flight hours before being admitted to the program. Still, the washout rate hovered at just under 50 percent. Out of 25,000 applications received, 1,830 women were accepted and of those 1,074 completed their training.

Ruth Westheimer (2nd from left) and fellow trainees at Avenger Field. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.155

The 30-week training program at Sweetwater included 210 hours of flying time on a wide variety of military aircraft. The training culminated in a graduation where the pilots received their wings, often pinned on by Cochran herself. Whether the civilian graduates would receive wings like their military pilot counterparts was initially questioned by some. And Cochran personally funded the purchase of the insignia for the first seven graduating classes (43-1 through 43-7).

The WASP went on to their assignments, ferrying planes from factories to airbases, “test-hopping” planes that other pilots had flagged as unreliable, and even towing targets used to train anti-aircraft gunners.

Class 43-6 included 22-year-old Ruth Westheimer. Raised by German Jewish immigrant parents in Jackson, Michigan, Westheimer was fascinated by flying from a young age, watching planes at the airstrip near her home. After graduating from Jackson High School in 1939, she plotted her path to the skies and attended the Civilian Pilot Training Program while studying at Jackson Junior College. She took a job as a secretary at Montgomery Ward & Co. in Chicago until she jumped at the opportunity to fly. Accepted for WASP training in April 1943, Westheimer initially failed the required day-long physical exam due to insufficient lung capacity. Determined to fly, she recognized what was holding her back and brazenly demanded to be tested again after removing her brassiere. She passed and became part of Class 43-6. In Sweetwater, Westheimer flew a variety of planes, but her favorite was the AT-6 “Texan” training aircraft. Westheimer loved ferrying duty.

Ruth stands in the foreground with her trainee roommates at Avenger Field. Ruth’s caption reads, “This is half of our bay. The gal with the magazine and pigtails is Mac. Bernie is the other one. Both are kids.” / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.073

For a time, Westheimer was based not far from home, with the 3rd Ferrying Group at Romulus Army Air Field in Michigan. At the same time, Chinese American Hazel Ying Lee was also flying out of Romulus. Lee is a tragic example of the extreme risks inherent in the WASP’s work. Lee was later transferred to Texas for Pursuit School training. She died on November 25, 1944, two days after a collision while transporting a P-63 Kingcobra fighter aircraft. She was the last of 38 WASP who died in service.

Clipping from Ruth’s scrapbook showing Hazel Lee and her husband. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.237

February 1944 travel orders for Westheimer and Hazel Lee from Romulus to Montreal. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.244

During one of Westheimer's assignments, flying with a group from Montreal to New Jersey, the WASP ran into weather trouble. Navigating visually, she eventually found an airfield and was assisted in landing by military personnel. Westheimer later said, “You should’ve seen the surprise on their faces when they saw a 120-lb girl in uniform climb out of the cockpit of that large military plane.”

Ruth Westheimer steps out of a Fairchild PT-19A primary trainer aircraft at Avenger Field on May 6, 1943. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.017

WASP often carried out their missions in a hostile atmosphere. Despite the shared purpose of American victory, not everyone wanted the women to succeed. There was even some resentment from male pilots who wanted the women’s stateside jobs rather than overseas combat duty.

In March 1944, Cochran and Army Air Forces Commander General “Hap” Arnold presented a strong case for militarization of the WASP before Congress, but the push was unsuccessful. With the war in Europe won and the war in the Pacific winding down, the WASP militarization bill was defeated in the House of Representatives on June 21, 1944. With no active path to service, the WASP were dismissed and their program disbanded, finalized on December 20, 1944. The devastated women even had to pay for their own fares home. Some were able to get contract work with Air Transport Command or flying in other capacities, but many returned to prewar occupations or began new lives.

Ruth’s graduation announcement from Class 43-W-6. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.207

Ruth Westheimer moved to Boyne City, Michigan, with her husband, 10th Mountain Division Army veteran Marshall Neymark. They raised four children, and she worked at city hall as treasurer. Later in life, Ruth made her way back to flying. Her second marriage to Boyne city manager and pilot Forbes Tompkins returned her to the cockpit. She renewed her pilot's license and began to fly again in their Cessna. After Forbes retired, Ruth stepped into the position of city manager, the first time the position was ever held by a woman.

The WASP were finally recognized for their service in 1977, when they were retroactively granted veteran status. In 2009, a bill passed to award the Congressional Gold Medal to the WASP. At the U.S. Capitol ceremony in March 2010, Ruth was one of the 200 (out of 300 surviving) WASP present to receive her award. She considered herself a “Lucky Lady,” in the right place at the right time. Ruth passed away in 2016 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery — a right that would not have been afforded during the war.

This guest blog was written by Kimberly Guise, Senior Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs at The National WWII Museum, and Curator of Our War Too: Women in Service, currently on display at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation now through September 7.

The roof of The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation covers nearly 12 acres. A one-inch rainfall results in almost 326,000 gallons of water landing on that expansive roof.

Where does the runoff go?

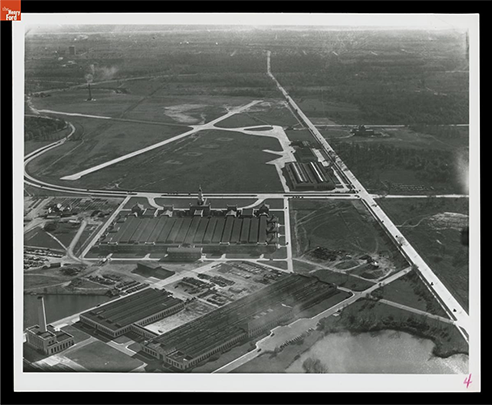

The architect, Robert O. Derrick, and landscape designer, Jens Jensen, who planned the building and grounds, cloaked the infrastructure that managed that runoff deftly. The following article walks you through the route that the water takes as downspouts and pipes move it from the museum roof to a 2.5-acre pond behind the museum and on to the nearby River Rouge. Today the pond, out of sight to the public, plays a vital role in reducing the risk of flooding and silt buildup in the nearby River Rouge, and it enables the reuse of runoff to irrigate the grounds.

Pond located north of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and southeast of the Dearborn Transit Center (upper right). / Drone photograph courtesy of Bart Fraley.

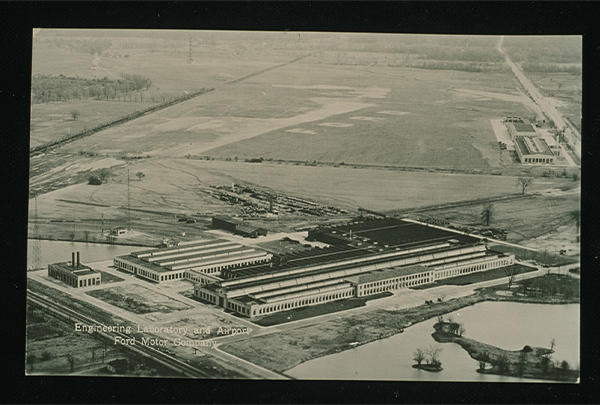

The pond predated the 1929 founding of The Edison Institute.. It and another set of ponds to the west resulted from clay extraction by a local brickyard. The Ford Motor Company built a powerhouse next to the eastern most pond at the Ford Engineering Laboratory. This pond became the holding tank for runoff from the museum roof.

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Landscape architect Jens Jensen mapped “the pond” behind “the museum building” in December 1931. Moving water from the roof to the pond begins with downspouts embedded into museum walls and structural columns throughout the Great Hall. Because this flow enters the system above ground, gravity moves it into the drainage infrastructure under the museum.

Rainwater also flows into yard drains around the museum. Since the yard drains are below grade, the system needed pumping stations to collect and pump water vertically to send water up and into the roof-water collection system closer to ground level. Architect Robert O. Derrick incorporated two pumphouses into his museum plans in 1928 to house these pumping stations.

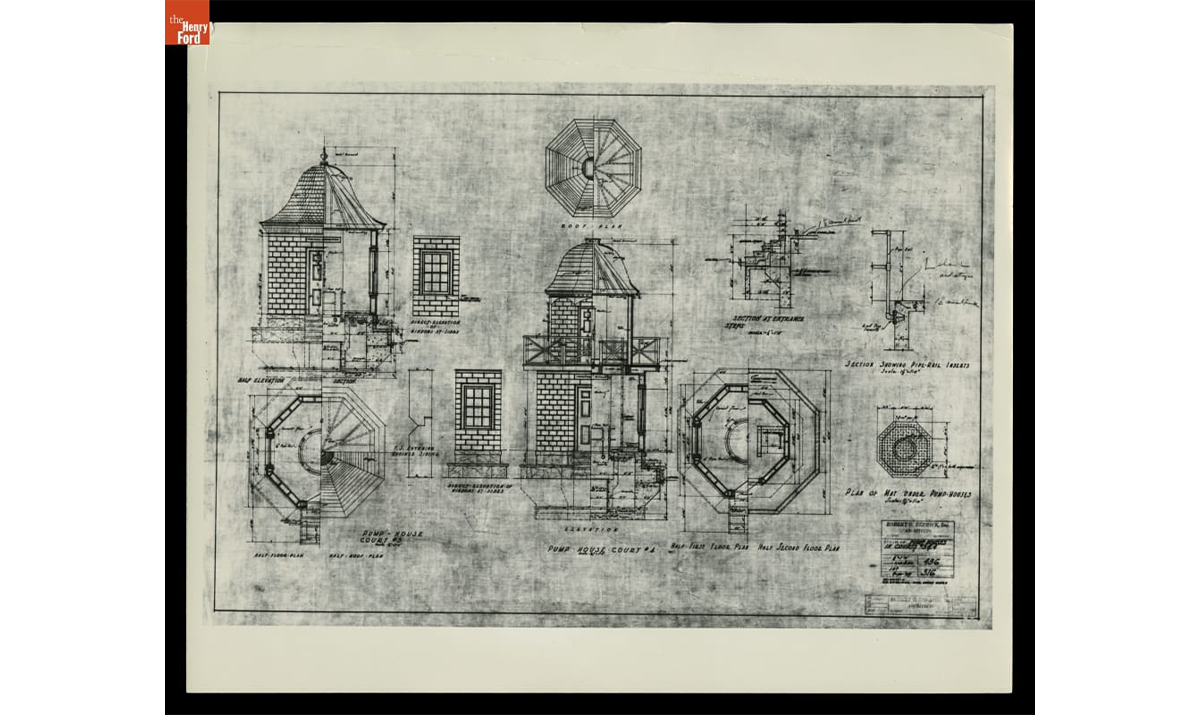

Derrick, noted for his Colonial-revival designs, disguised the pumping stations in reproductions of other structures popular during the Colonial-revival era. The inspiration included a garden feature from Mount Vernon, home of George and Martha Washington, and the observatory that astronomer David Rittenhouse built in Philadelphia after he moved there in 1770. Rittenhouse gained international attention in 1769 because of his observation of the transit of Venus. His relocation to Philadelphia in 1770, the largest city in the Colonies at the time, facilitated his engagement with the vibrant scientific community there. Contemporaries described his Philadelphia observatory as “a small but pretty convenient octagonal building, of brick” [William Barton, Memoirs of the Life of David Rittenhouse (1813), note 111].

Virginia Court pumphouse based on a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

Pennsylvania Court pumphouse based on Rittenhouse’s observatory, 1928 / THF294392

The stations, located in each of the two large courtyards on each side of the main entrance to the museum, hold water and pump it into the stormwater infrastructure as needed.

Details of pumphouses in museum courtyards, drawn by Robert O. Derrick, Inc., Architects, 1929 / THF98551

Gravity facilitates rainwater flow to a 24-inch main line under the museum, which channels runoff to the basement of the powerhouse in the back of the museum. Facilities staff replaced the entire ductile iron system in the powerhouse basement during 2025 with stainless steel. This was the first replacement since the entire system was built in 1929.

Storm-pump system in the powerhouse basement. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

Two 75-horsepower motors, located in the basement of the power house, handle large storms. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

In what's designed as a "wet" system, water always fills the lower portion of the infrastructure. As rainwater drainage increases the pressure in the system, it pushes water out of the museum and into the retention pond.

What happens after rainwater runoff enters the pond?

The retention pond allows sediment to settle out of the water within the pond rather than in the River Rouge. It also accumulates for later use to water the grounds around the museum, Lovett Hall, and the Josephine Ford Plaza. A large irrigation pump draws water from the pond to the irrigation piping.

The stormwater management system within Greenfield Village converges near the Suwanee dock and flows into the Suwanee Lagoon. The water in the lagoon is regulated by a drain that flows into the Oxbow which connects to the River Rouge. Facilities staff can use a pumping station at the Oxbow to increase the rate of pumping into the River Rouge in case of excessive rainfall. That pumping station also works as a protection. If the River Rouge is too high, a valve can be exercised to prevent backward flow into The Henry Ford's stormwater management system.

Each pond in the Village serves as a large holding tank with an inlet on one side and outlet on the other, depending on which direction the water needs to flow to reach the Suwanee.

Mill pond construction in the Greenfield Village craft area, March 2003 / THF10348

Mill pond in Greenfield Village’s craft area. / Photograph courtesy of Lee Cagle, May 2018.

Water within the system irrigates lawns and gardens within the Village. A large irrigation pump near Henry Ford Academy draws water from the Suwanee Lagoon for this purpose.

Overall, the water management system has been integral to The Henry Ford’s efforts to reduce waste and reuse runoff. An overview of five years of Green Museum Work undertaken from 2019 through 2024 acknowledges this system as one of the historic precedents and an inspiration for current efforts. It takes staff expertise, financial commitment, and regular maintenance to continue such efforts, but the investment pays off in reduced water bills and healthier riverine ecosystems. Updates to the system during 2025 should prepare it for the next 100 years.

Jon Bennett is Assistant Construction Manager and Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. The title of this blog was inspired by Al Green’s and Mabon “Teenie” Hodges 1974 song by the same title.

From Frames to Film at Ford Motor Company

Did you know that the Ford Motor Company was not only a pioneer in the automotive industry but also involved in the world of filmmaking? .

In the early years of the Ford Motor Company, various photographers and firms were hired to capture images, leading to the creation of the Ford Motor Company's Photographic Department. Their initial purpose was to document production methods, provide illustrations for publications, and promote Henry Ford and his company. This was the backbone that sparked another of Henry Ford's interests: filmmaking.

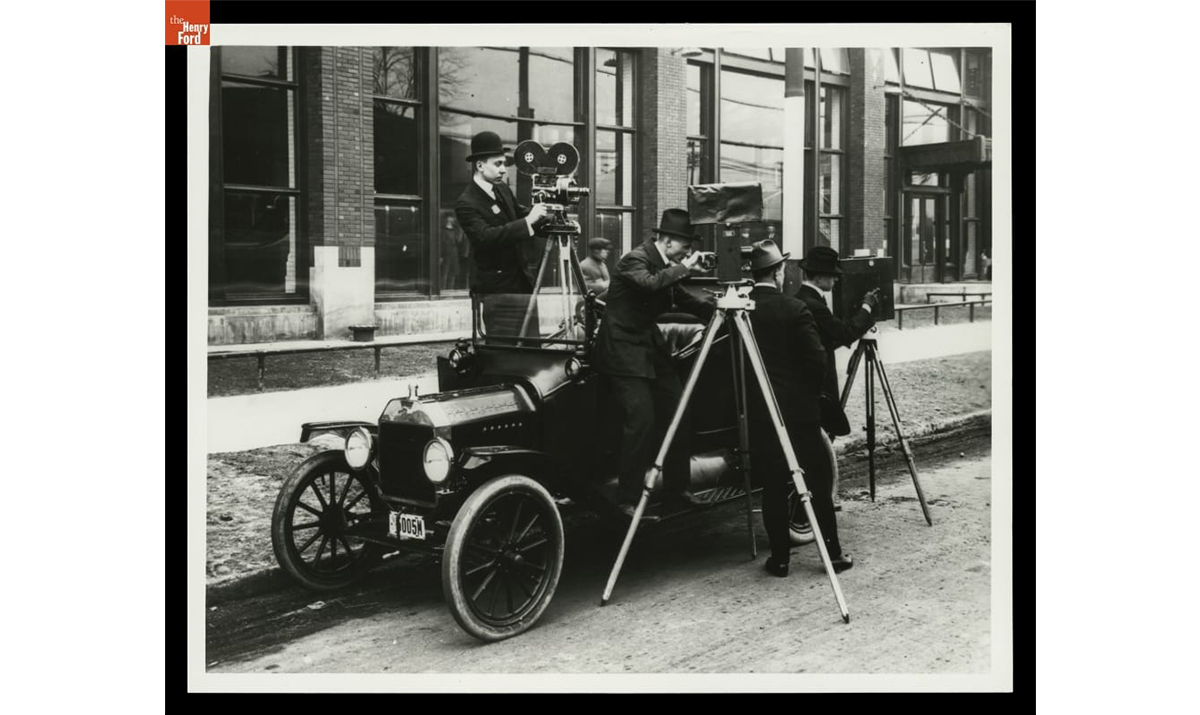

Henry Ford developed an interest in filmmaking in 1913 after he saw a film made by an external company about the Highland Park automobile factory. By April 1914, he instructed Ambrose B. Jewett from Ford’s Advertising Department to procure a camera and an operator. Within months, the company became established for their use of film in advertising, as documentation, and as a way to share industrial processes with the general public.

Ambrose B. Jewett of Ford Advertising Department is visible at center, with painter Irving Bacon (left) and Henry Ford (right), 1919. / THF95164

Henry Ford was fascinated by the potential of motion picture film to train workers and communicate daily news to the public, including scenes from their lives and the wonders of manufacturing at the Ford Motor Company. Starting with a modest two-man team in 1914, the Motion Picture Department expanded to 24 members, acquiring advanced 35mm cameras and establishing a film processing operation at the Highland Park Plant, comparable to Hollywood studios. By 1915, they began releasing news reels as “The Ford Animated Weekly.” Each episode covered a variety of current news events, such as the launch of the U.S.S. Arizona and the Liberty Bell on tour for the Panama-Pacific Exposition, in addition to animated segments.

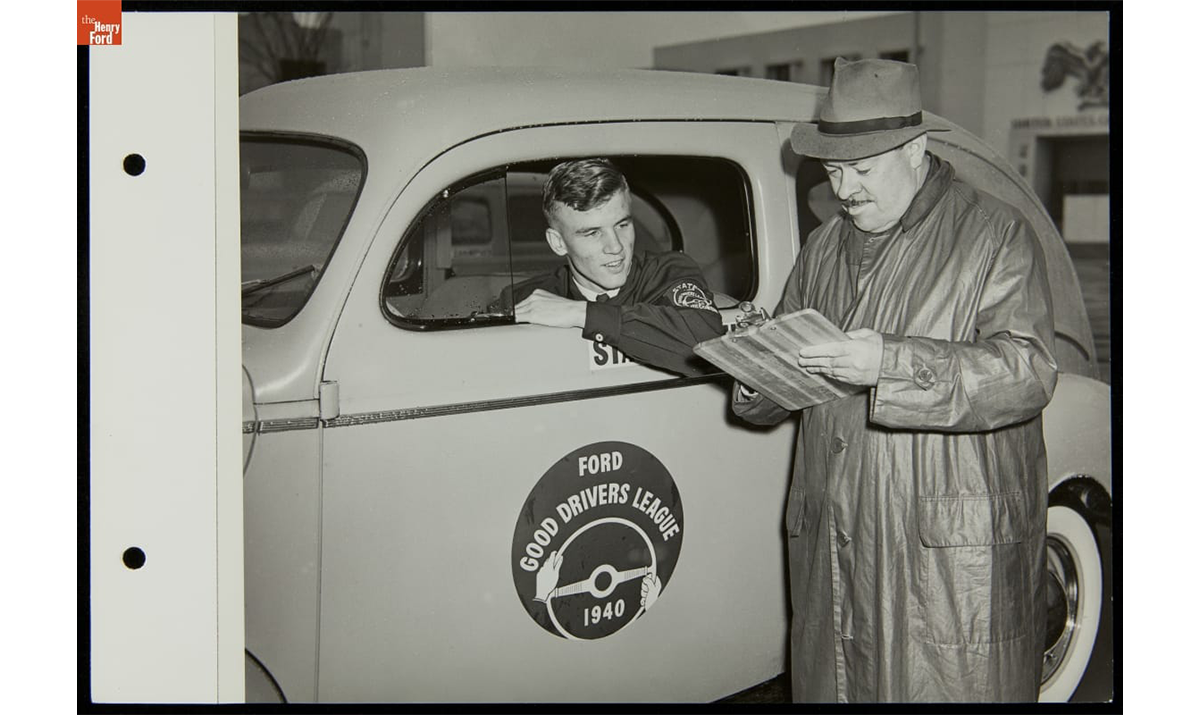

The company's inaugural film, "How Henry Ford Makes One Thousand Cars a Day," naturally centered on its own processes. Initially, the department concentrated on current events and educational content; by the 1920s, it had shifted towards promoting popular themes like road quality, safety, and advanced farming techniques. As early as 1917, they recognized that film could assist in educating factory workers in their repair work by slowing down footage of fast-moving machines--a notion highlighted in an article from “The Ford Man” published on September 20, 1917.

Article from "The Ford Man" periodical, September 20, 1917 / Image by staff of The Henry Ford

The Ford Motor Company Photographic Department was responsible for both motion pictures and still photography, remaining the only department of its kind until 1918. It was initially housed in the administration building at the Highland Park Plant, moving to the administration building at the Rouge Plant in Dearborn, Michigan, in the mid-1920s. In 1956, it relocated again, this time to the World Headquarters on Michigan Avenue in Dearborn.

Workers at Cutting Tables and Copy Camera, Ford Photographic Department, Highland Park Plant, 1914. / THF124964

Initially, the department's photographers focused on documenting the company's products, facilities, and workforce. However, following the move to the Rouge Plant, the focus gradually shifted toward public relations and promotional activities. While few internal documents regarding the department's organization and management have survived, the negatives and photos preserved in the company's archives from the 1950s were ultimately donated to The Henry Ford in 1964. Notable photographers who worked for Ford Motor Company include George Ebling, Joseph Farkas, Michael Malley, E.S. Purrington, William Stettler, and C.E. Wagner.

Ford Motor Company Photographers with Ford Model T Touring Car outside the Highland Park Plant. / THF119387

For years, the Ford Motor Company was one of the world's major film producers, with its films reaching audiences both nationally and internationally. These films were distributed through Ford branches to Ford agents, who then screened them in theaters within their respective territories.

In 1956, Ford Public Relations films achieved a record audience of over 24 million viewers worldwide. The total audience for the year, excluding television, reached 24,267,455, reflecting significant growth in both domestic and international viewership. Throughout the 1950s, the types of films produced included categories like the Automobile Industry, Americans at Home, Vacation Films, Educational Subjects, and Driver Education Films.

Young Man Taking Driver's Test, Ford Good Drivers League, Ford Exposition, New York World's Fair, 1940. / THF216125

In 1963, Ford Motor Company gifted over 1.5 million feet of motion picture film, created between 1914 and the early 1940s by its Motion Picture Department, to the United States National Archives. The Ford Film Collection provides comprehensive coverage of the era's current events, educational topics, and special interests. The Henry Ford's Benson Ford Research Center secured permission on December 15, 1994, to reproduce and distribute high-resolution copies from the National Archives of those collections relevant to the early days of the Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford's personal endeavors, and subjects associated with The Henry Ford. The versions available in our online catalog and on YouTube are low-resolution samples with time codes, such as "Ford and the Century of Progress, Part 2."

The Ford Motor Company's journey from still photography to motion pictures is a testament to its innovative spirit and commitment to communication and education. By embracing filmmaking, Henry Ford not only documented the company's achievements but also shared the wonders of manufacturing and modern life with the world. Thankfully, Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company had such a passion and dedication to keep this work flowing, and it is now available for research. If you’d like to learn more about this collection or others, please email us at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Stephanie Lucas is a Research Specialist at The Henry Ford.

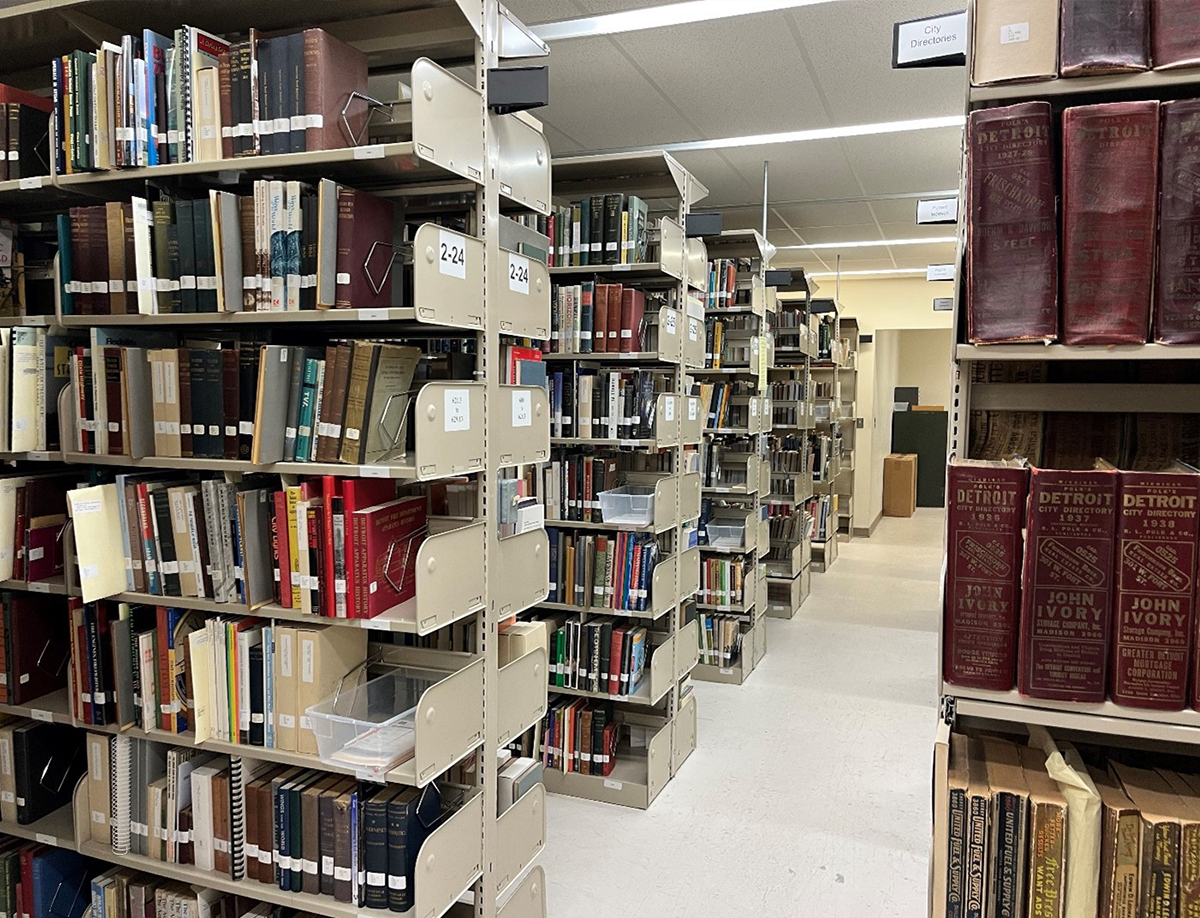

If you asked someone to picture a library, most would think of their local public library that presents the most recent, riveting, and relevant titles on their shelves. What they might not picture is the library here at The Henry Ford. Located in the Benson Ford Research Center — which you might have seen if you ever visited the Reading Room or parked across the street while in the back of the museum — is the Archives and Library collection at THF. The Henry Ford’s library is a little bit different from a public library because our team adds books to the collection based on their fit with THF’s mission and vision of American innovation!

The library stacks in the Benson Ford Research Center. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

One thing that the library collection at THF does have in common with a public library is that our staff are passionate about stewarding these collections for current and future learners. When it became clear that open shelving space for new books was decreasing, the library team decided they needed to act quickly. To begin addressing these space limitations, I joined the Archives and Library team as an intern to conduct a capacity study of the library collection’s storage.

During my internship, I calculated the total amount of space being taken up and the total amount of storage space available, and compared these numbers. Without a standardized system for measuring library storage or for assessing capacity I ran into some difficulties trying to get an accurate view of how full each shelf was. After some trial and error, I eventually adopted a system used by the Archives and Library staff to assess the capacity of the library storage along a scale of 0%, 25%, 50%, 75% to finally, 100%. These somewhat broad values allowed me to assess how full the shelves were, taking specific book storage best practices into account while measuring. As I embarked on this project, I found there were many unlabeled shelves and incomplete floor plans, which complicated how I collected data. After many weeks of measuring the total space available and assessing the capacity of each shelf, I found that the three floors of library storage are just over 70% full!

The archives in Benson Ford Research Center. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

Once I determined how much space was being taken up, I then needed to find the best solutions for addressing these all-too-common space constraints. After some research, I found that there were five potential solutions, each with its own level of applicability for the library collection. These solutions included:

- Shifting

- Deaccessioning

- Digitizing

- Installing compact shelving

- Renting off-site storage

Most of these options, despite being a good fit for libraries across the country, were not ideal for us at The Henry Ford. After assessing each solution in a rubric with categories, including collaboration, cost, efficacy, and time, I found that shifting and installing compact shelving were two of the best solutions. While neither of these are an immediate fix, they each provide opportunities to help our Archives and Libraries staff to steward the growing collection for generations of scholars to come!

Julia Noriega was a Ford Foundation Diversity and Inclusion Intern for Archives and Libraries at The Henry Ford

Dr. Sullivan Jackson: Saxophonist

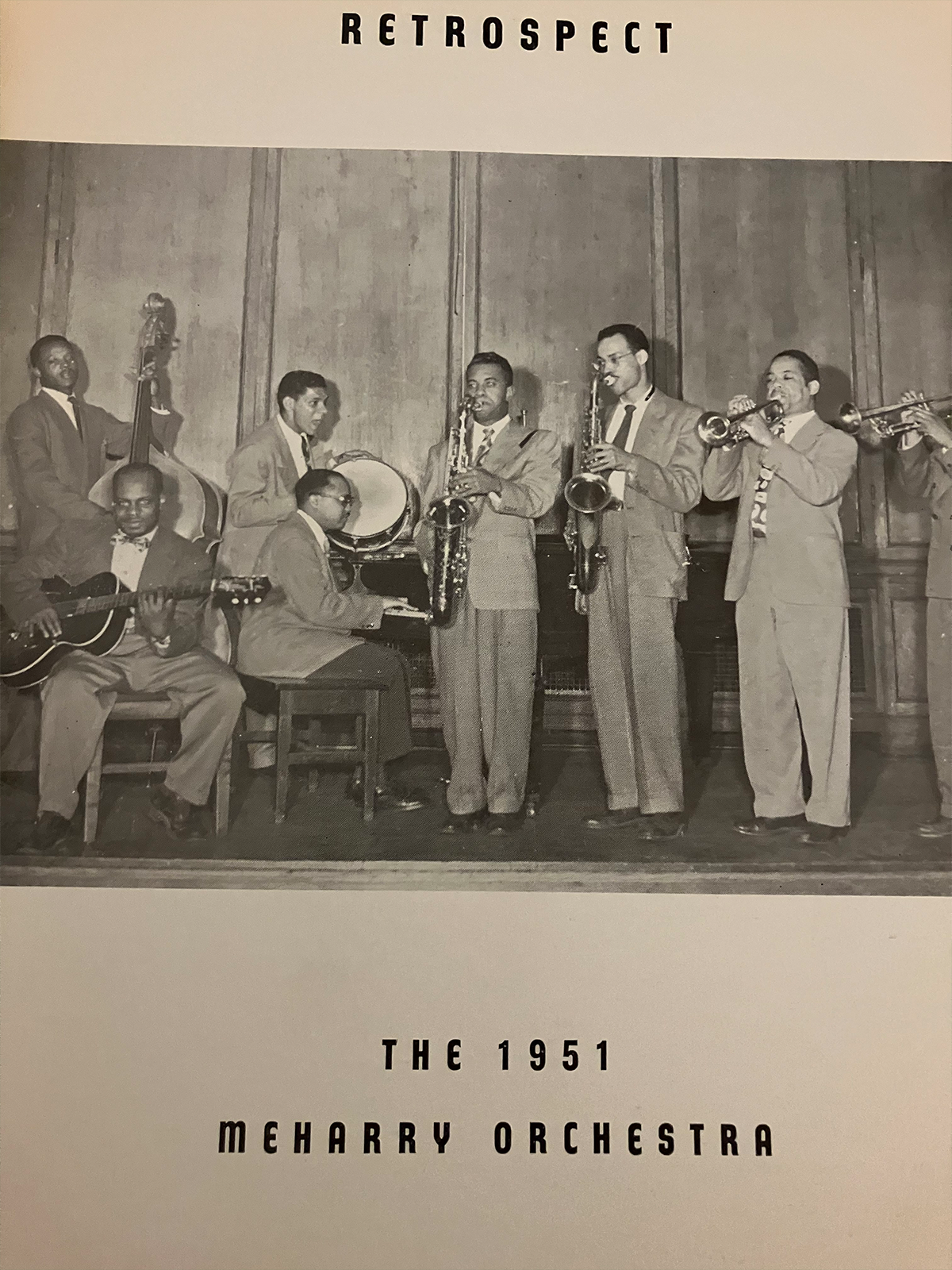

Music is a part of the Jackson family story, from the piano lessons that first brought young Richie Jean Sherrod soon-to-be-Jackson and young Coretta Scott soon-to-be-King together to the family's music room. In fact, Dr. Sullivan Jackson played tenor saxophone prior to his career as a dentist serving Selma's Black community. Dr. Jackson's time as a musician in the mid-1940s to the early 1950s allowed him to participate in Black American music cultural changes.

This picture of the Meharry Medical College Orchestra from the 1951 Meharrian yearbook shows Dr. Sullivan Jackson (center) playing the saxophone as a third-year medical student. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

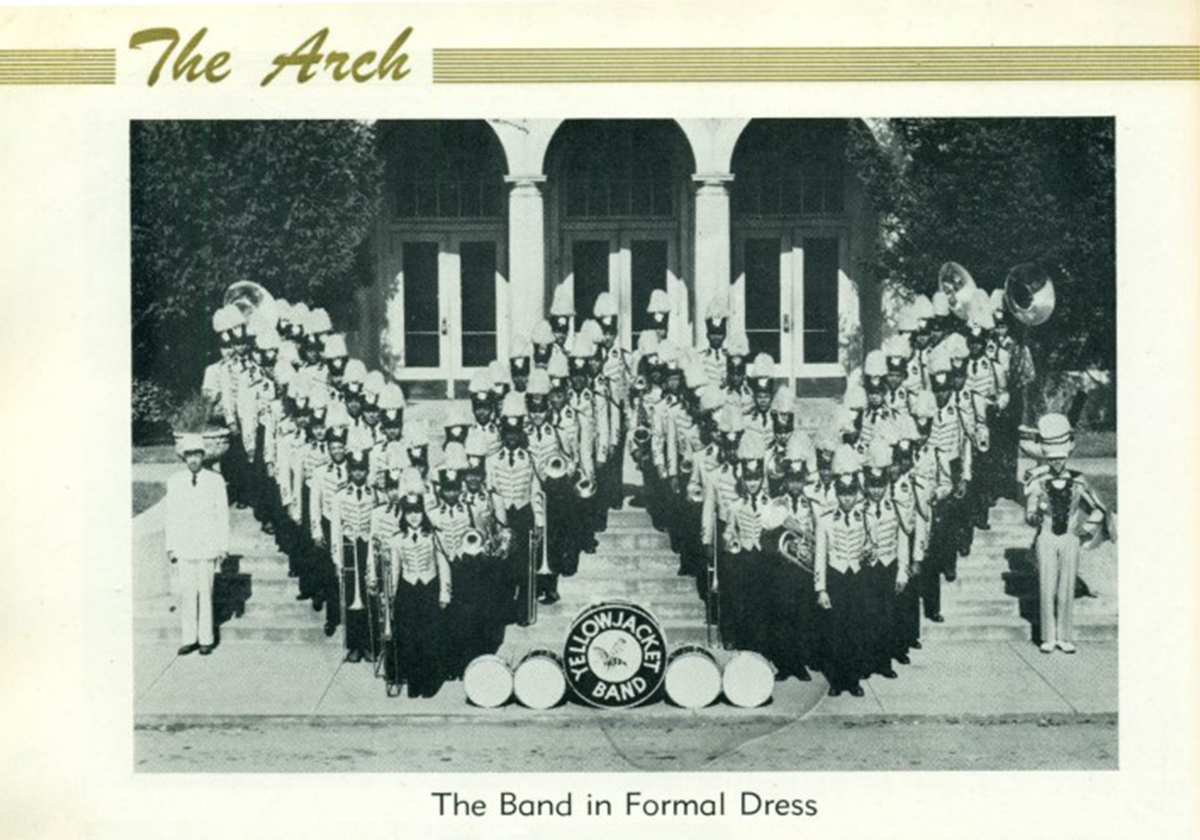

Following service in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, Sullivan Jackson enrolled at West Virginia State University (WVSU), one of 107 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). He joined the WVSU Yellow Jacket collegiate band as a saxophonist in the mid- to late1940s, a time when marching band culture at HBCUs was evolving.

Collegiate marching bands originate from U.S. military bands that played music to boost soldiers' morale and keep tempo during long marches. Starting in the 1840s, American colleges founded marching bands on their campuses and in the 1890s, Tuskegee Institute — now Tuskegee University — became the first HBCU to have a band. At most colleges marching bands were a part of Reserve Officers' Training Corps programs during this time. For example, Tuskegee's marching band was a part of the school's military science department — not the music department — prior to 1931.

Tuskegee Institute Football Pennant, 1920-1950. / THF157606

World War I changed the type of music that bands played at HBCUs. Between 1917 and 1918, the U.S. Army mobilized 27 new Black regiments, all of which established regimental bands. The approximately 1,000 Black musicians mustered out for service in these bands included collegiate conductors and music professors from HBCUs. While standard military marches were a part of the regimental bands' repertoires, they also played popular music such as Missouri-style ragtime and New Orleans-style jazz. After the end of the war, the veterans returned to their jobs at HBCUs and conducted collegiate bands to play both march music and popular songs as they had during the war.

This evolution reached a crescendo in the mid-1940s while the future-Dr. Jackson was at WVSU. In 1946, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College — now Florida A&M University — hired William P. Foster to direct the school's marching band. Foster recruited returning GIs, professional musicians and high school students to play in FAMU's band. Foster's musicians performed solely popular music, building on the legacy of Black regimental bands during World War I. They also marched in elaborately choreographed and physically demanding routines that played well in newsreels and later on television. Over the following years, other HBCU bands adopted Foster'sflair for pageantry and emphasis on contemporary music and choreographed spectacles. Even Dr. Jackson's own West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket marching band posed in a W-shaped formation in the school's 1948-49 yearbook, demonstrating this cultural change at HBCUs. This legacy remains the gold standard of band performance at HBCUs today.

West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket Band, circa 1948. / Via West Virginia State University Drain-Jordan Library

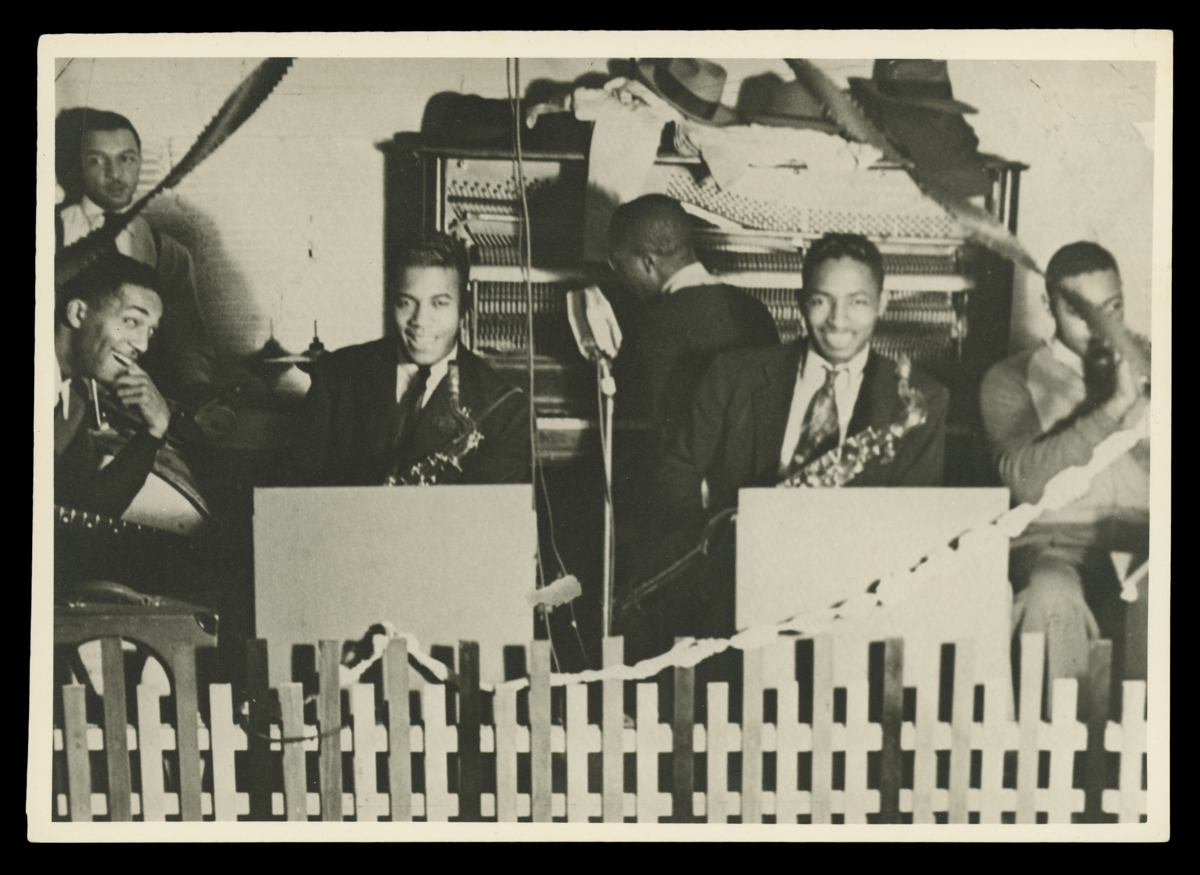

After graduating from WVSU, Sullivan Jackson pursued a degree in dentistry from Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. During that time, Dr. Jackson played saxophone in a band called the Doctors of Rhythm. The Doctors of Rhythm toured in what became known as the Chitlin' Circuit.

Sullivan Jackson with His Band, Date Unknown. Sullivan Jackson is seated second from the left holding his saxophone. / THF719998

Exclusionary segregation practices in the United States meant that traveling Black entertainers could not go to certain venues. In the 1920s, the only booking agency that served Black musicians, comedians, dancers or singers was the Theater Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.). However, performers who were booked through T.O.B.A. paid their travel expenses out of pocket and could only play at White-owned T.O.B.A.-affiliated venues.

When the Theater Owners Booking Association folded due to financial collapse in the 1930s, an informal network of Black booking agents and venues for Black clientele arose in its place. Performers now had the freedom to play where they liked: from large theaters like the Apollo in Harlem to the hole-in-wall juke joints in small towns like Hobson City, Alabama. This network was later called the "Chitlin' Circuit." The name is a riff on "Borscht Belt" venues that primarily booked Jewish American entertainers for Jewish American audiences; it is also a reference to chitterlings, a controversial staple of Southern American cooking.

The Orioles Music Group inside Fox Brothers Clothier, Chicago, Illinois, 1942. The Orioles were a pioneering rhythm and blues group that performed on the Chitlin' Circuit in the 1940s and 1950s. / THF184199

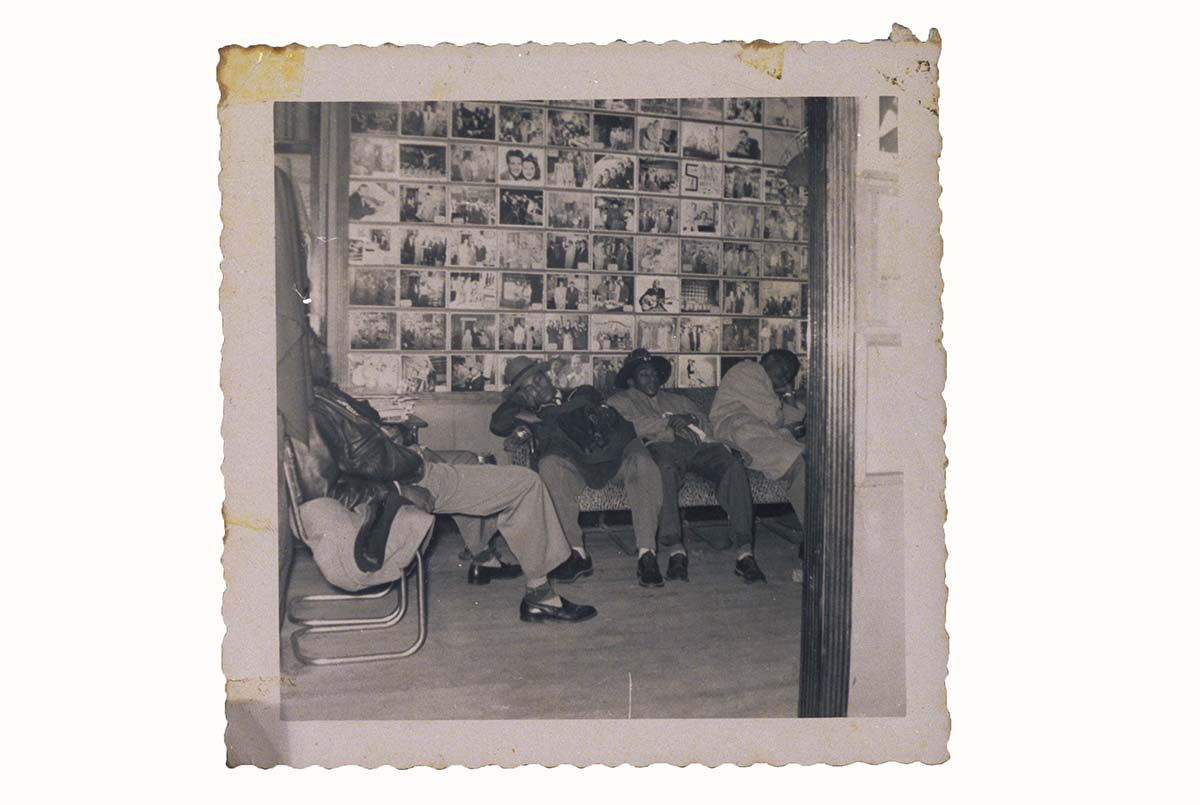

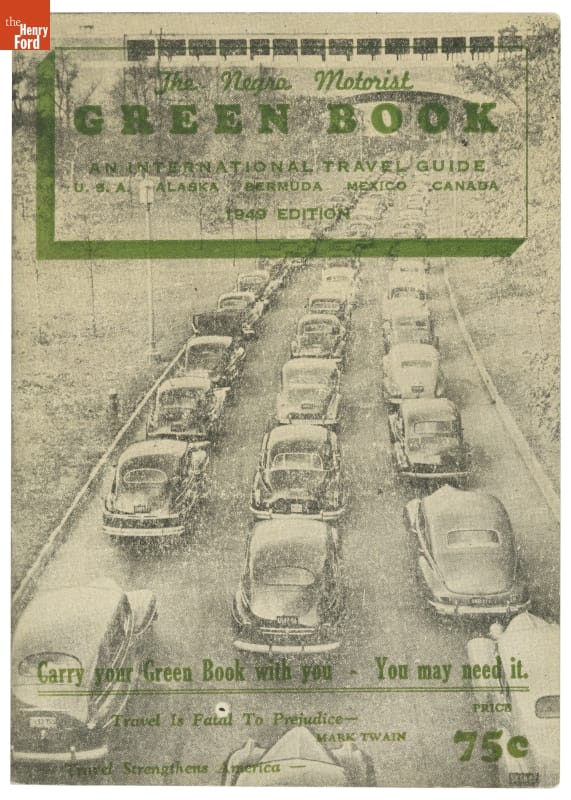

Performers like Sullivan Jackson appreciated the freedom afforded to them on the Chitlin' Circuit, but faced challenges on the road. Johnny Shines, a blues musician who toured the Circuit in the 1940s, described most venues as "rough" places where drinking, gambling, and fighting were common. Chitlin' Circuit audiences were notoriously harsh critics; the Apollo Theater emcee, "Sandman" Sims, used props like a hook or broom to kick acts off stage if the crowd booed them. Most venues paid the artists very little; sometimes payment came in the form of a hot meal instead of any money. Even traveling between shows could be perilous. Many Chitlin' Circuit performers had to drive all night to find safe lodging and were refused service while on the road. With Jim Crow laws in the South and thousands of sundown towns throughout the country, performers had to rely on resources such as the Negro Motorist Green Book and the hospitality from the communities they played in for travel, lodging, and food.

"Negro Motorist Green Book, An International Travel Guide," 1949. / THF77183

For a lucky few — like Chitlin' Circuit veterans Tina Turner, James Brown, Richard Pryor, or Jimi Hendrix — touring the Circuit was excellent training for their later famous careers. But even a short-lived entertainment career like Dr. Sullivan Jackson's provided Black performers with an opportunity to grow as artists and work within their own communities.

After graduating from Meharry Medical College, Dr. Sullivan Jackson became a dentist in Selma, Alabama, started his family and took part in the struggle for civil rights. But his connection to the music world was not severed. Among the Jackson family's many and frequent guests, traveling musicians — some of whom he played with — were also welcomed into the home. And Dr. Sullivan Jackson kept his tenor saxophone over the years and it is now part of the collection of The Henry Ford.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson's Selmer Mark VI Tenor Saxophone, 1968. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Molding the Future with Mold-A-Ramas

Visitors to The Henry Ford are likely familiar with the iconic Mold-A-Rama machines scattered throughout the museum. Loud, colorful, and with that distinctive “Mold-A-Rama” smell of warm plastic, they have spit out affordable souvenirs for thousands of guests over the years. The Henry Ford boasts 10 Mold-A-Rama machines, made more impressive when you consider only a few hundred machines were ever produced.

“Antique Automobile” Mold-A-Rama machine at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

Like all things at The Henry Ford, Mold-A-Rama machines are a story of classic American innovation. They were invented in the 1950s by John H. “Tike” Miller, after he sought to replace a broken figurine in his Nativity set. When he was unable to buy a single figurine from his local department store, he made his own from plaster. This would eventually lead to a business selling plaster figurines and then experiments with plastic injection molding machines. These advancements in molding machine technology would allow Miller to sell thousands of plastic figures out of his Illinois factory.

Final patent for John Miller’s plastic mold injection machine. / Courtesy of Google Patents

At the end of the 1950s Miller’s company declared bankruptcy, and Miller licensed the rights to his machine to Automatic Retailers of America Inc. ARA would go on to produce hundreds of Mold-A-Rama machines throughout the 1960s. Mold-A-Ramas were featured at both the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and the 1964 New York World’s Fair, and in 1966 they were installed at their first permanent location, the Brookfield Zoo (where they can still be found today!). After this, Mold-A-Ramas could be found in popular tourist destinations, restaurants, and even interstate rest stops. Experts estimate these golden years produced up to 300 unique moldsets for 200 machines.

Disaster struck soon after, when ARA elected to dissolve the Mold-A-Rama division of the business in 1968. The company cited high upkeep costs and excessive maintenance required as the reason for closure, a problem that continues today. By the 1970s, the original Mold-A-Rama Inc. had completely shut down.

When the company closed, both the Mold-A-Rama machines and operating locations were snapped up by various interested entrepreneurs. One such innovator was William A. Jones, a Michigan State graduate. Dissatisfied with his position as a corporate accountant, Jones purchased every Chicago area Mold-A-Rama machine and location from a retiring coworker in 1971. Ten years later, Jones would buy out a fellow operator to become the largest Mold-A-Rama company in the Midwest. In 2011, his company officially changed its name from The William A. Jones Co. to Mold-A-Rama Inc., marking the first time in 50 years that these machines were operated by their namesake. Today, Jones’s empire of wax spans seven locations across four states with nearly 60 machines.

Interestingly, the Mold-A-Rama machine has only one major competitor, the Mold-A-Matic. This story begins with store owner Eldin Irwin, who leased several Mold-A-Rama machines from ARA. When the company shut down production, Irwin purchased as much of the available inventory as he could and took the machines on the road. For years, he and his grandson would tour the country with the Mold-A-Ramas, visiting state fairs and carnivals. Like Jones, Irwin would expand his business dramatically in the 1980s. In this case, the Florida-based Mold-A-Matic Inc. wanted to sell their entire inventory, which Irwin acquired along with the name. Currently, the company is run by Irwin’s grandson and has 11 locations with nearly 50 Mold-A-Matic machines.

“1952 Weinermobile” Mold-A-Rama machine at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

In 2025, the dust has settled. While a handful of independently run Mold-A-Rama machines exist, Mold-A-Rama Inc. and Unique Souvenirs Inc. (formerly Mold-A-Matic Inc.) remain the only companies to service multiple locations. Both companies have remained in their respective families and are currently run by second- and third-generation Mold-A-Rama operators. The companies agree not to encroach on one another’s territories, and they even collaborate on occasion and share resources. This is especially necessary as the years pass and machines break down. Every Mold-A-Rama machine running today was built in the 1960s, and as time goes on, they become harder to repair—especially since their parts are out-of-production. Nearly 75 years after the Mold-A-Rama was first conceived, we are facing a future where it may fade out of existence.

Despite this, people’s love for the machines and their molds is still strong. Both Unique Souvenirs Inc. and Mold-A-Rama Inc. have websites providing information about the machines, their locations, and collectible molds. Griffin Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago recently hosted a temporary Mold-A-Rama exhibit, complete with additional machines and a rotation of retired molds. This exhibit was extended several times, and ultimately was so popular that it stayed on display for over two years.

Collection of current and retired molds at Griffin Museum of Science and Industry. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Display of a moldset and preliminary versions of the Mold-A-Rama at Griffin Museum of Science and Industry. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford

Outside of official channels, Mold-A-Rama fans share their experiences and collections on various social media platforms. It is truly impressive to see a machine that should have been made obsolete continue to thrive so many years later.

Rachael Monroe is Project Cataloging Specialist at The Henry Ford.

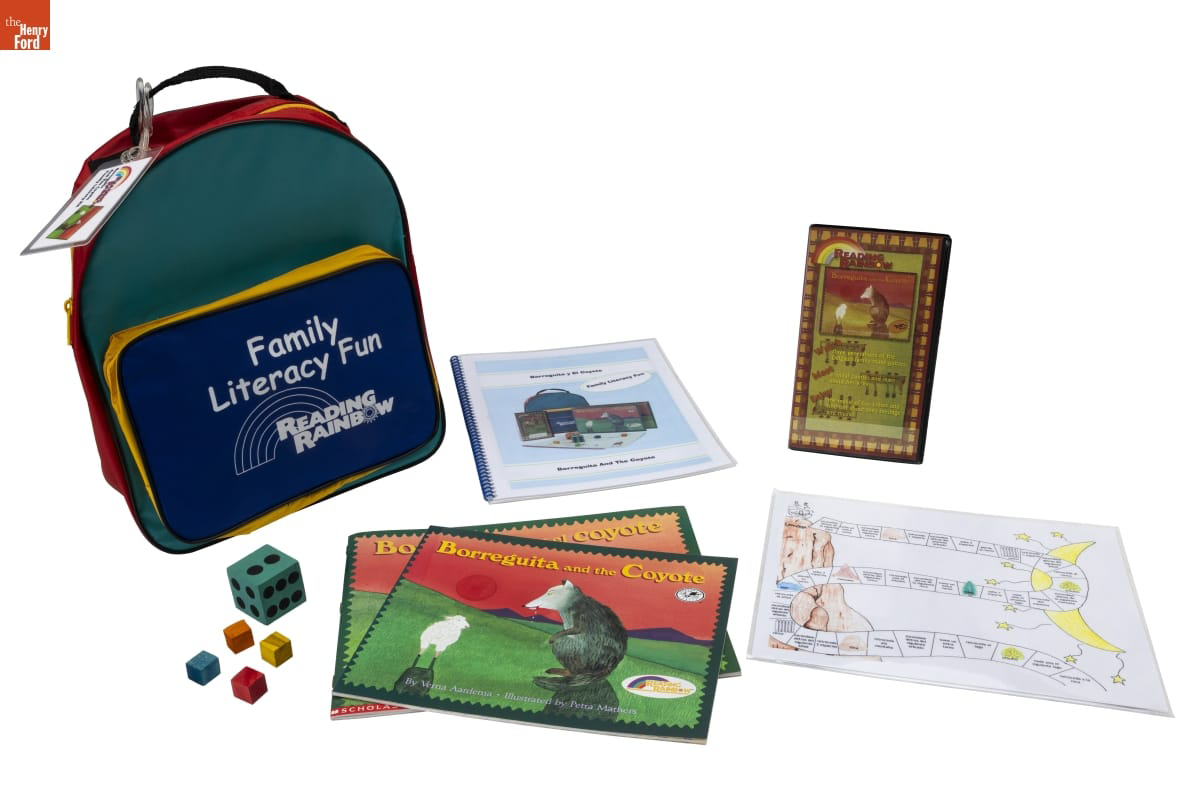

Assembled by the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), this colorful backpack contains English and Spanish language versions of the book Borreguita and the Coyote, a VHS tape of a television episode centered around the book, and bilingual activity booklet and board game designed to let families practice their language skills together. This kit was likely given to a library, community center, or school for distribution, before eventually making its way into The Henry Ford’s collection in 2024. It represents an extension of the efforts to promote children’s literacy and love of reading undertaken by a program that would come to influence a generation of children: the Reading Rainbow television show.

Reading Rainbow "Borreguita and the Coyote" Family Literacy Kit, 1999-2008. / THF198380

First airing in 1983, Reading Rainbow was developed to address the problem of children losing their reading comprehension skills over the summer break. Hosted by LeVar Burton, each episode focused on a different topic related to a featured book, and consisted of live-action segments with Burton, a celebrity narrating the chosen book, and recommendations for similar books that viewers could check out at their local library.

In the show’s early days, television was viewed as the enemy to education, and the show creators encountered initial skepticism. Despite this, and thanks to funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, throughout its 23-season run Reading Rainbow demonstrated that it did, in fact, boost children’s reading skills. As the show progressed, it was able to tackle more difficult issues, with notable segments including footage of a live childbirth, and LeVar Burton talking to the students of PS 234 as they returned to their school after being forced to leave in the aftermath of 9/11.

Season 6 episode “Robbery at the Diamond Dog Diner” saw Peter Falk reading the picture book, of the same name, and LeVar getting roped into working at a diner. This letter to “Dinerman” Richard Gutman, and other correspondence, indicates that he was helpful to the production team in their search for a diner to film in — a testament to the research the Reading Rainbow team put into their live segments. / THF715225

Despite its immense popularity — the show would receive over 250 awards including a Peabody and 26 Emmys and earn the title of the most-watched PBS program in classrooms — Reading Rainbow faced new challenges with the 2002 passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, which shifted funding from programs that taught children to love to read, and toward programs that taught them how to read. The final original episode aired in 2006, although reruns would continue until 2009.

Like so many objects in The Henry Ford’s collection, this kit allows us to tell multiple stories. It allows us to talk about one type of literacy. It adds to our collections related to popular children’s television shows. It gets to the experience of immigrants in America as they try to learn another language. All of these are valid lenses through which to view this kit, and all were cited as reasons why it belonged in our collection.

At The Henry Ford, we share something in common with Reading Rainbow — the belief that objects, like books, can expand our horizons through the stories they tell. But you don’t have to take our word for it!

To learn more about Reading Rainbow, check out the documentary Butterfly in the Sky. You can also find story segments from Reading Rainbow, along with related activities, on the Reading Rainbow website.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

When the United States entered World War II, there were immediate voids in the workforce left by those leaving to fight abroad. Women across the country heard a call to action and stepped in, taking on new roles previously held only by men.

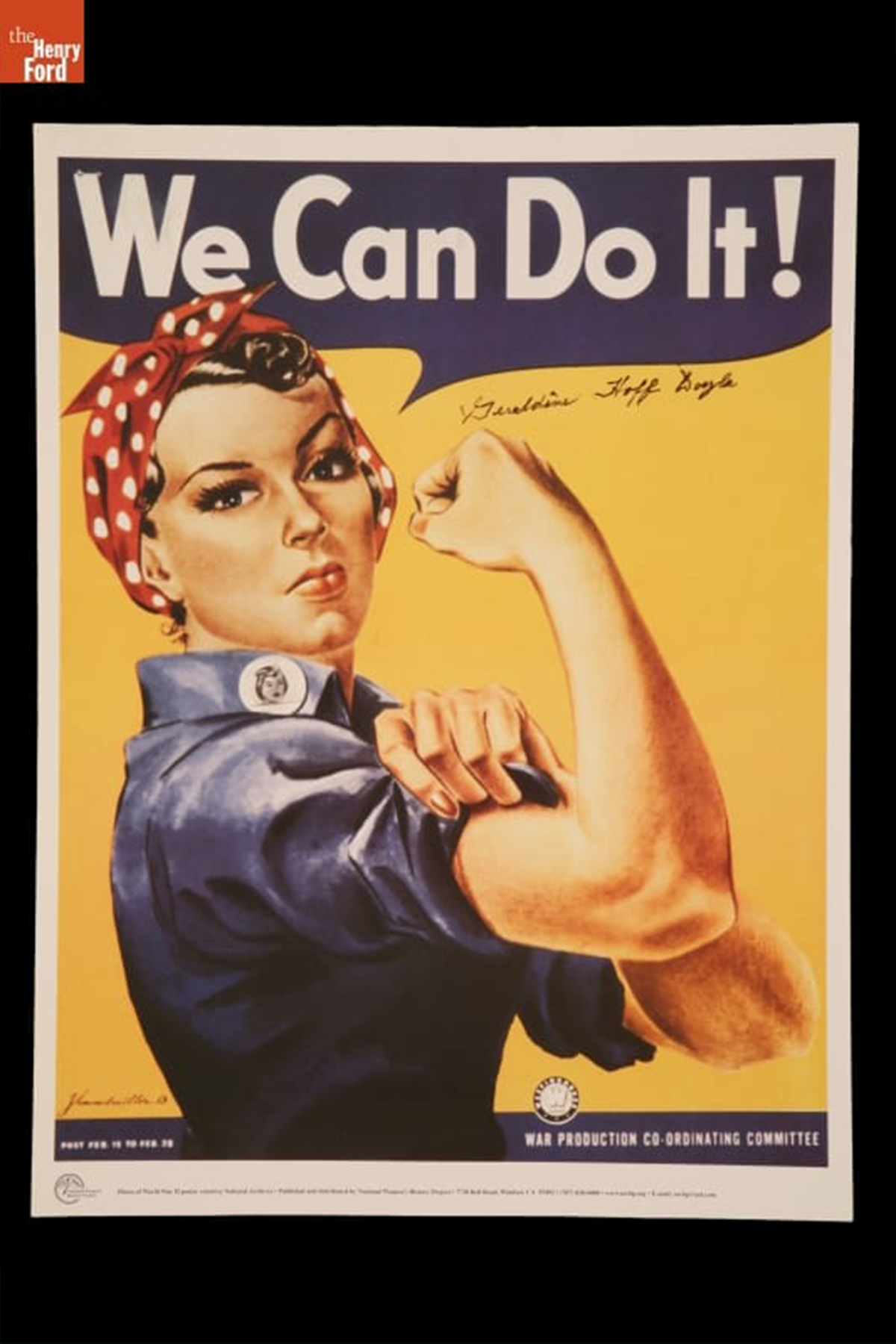

Popularized by the song Rosie the Riveter, Rosie became the fictional face of these early wartime women workers. Rosie was feminine, yet strong and powerful, changing the societal stigmas against working women and drawing interest in wartime work.

"Rosie the Riveter" sheet music, 1942. / THF290068

Reproduction World War II Poster, "We Can Do It!," 1998. / THF108519

Women across the country were inspired to join the ranks of Rosie but concerns over gender roles and domestic responsibilities discouraged others. However, as the war raged on and production needs continued to rise, the United States was faced with a manpower, or rather a womanpower, crisis.

Late in 1942, the War Manpower Commission announced a new campaign to recruit more women workers after estimating the majority of roughly five million new employees in 1943 would have to be women to keep up with war production demands. Ford Motor Company, placed at the center of the arsenal of democracy, was a leader in this campaign and shaping their facilities to attract more women to factory work.

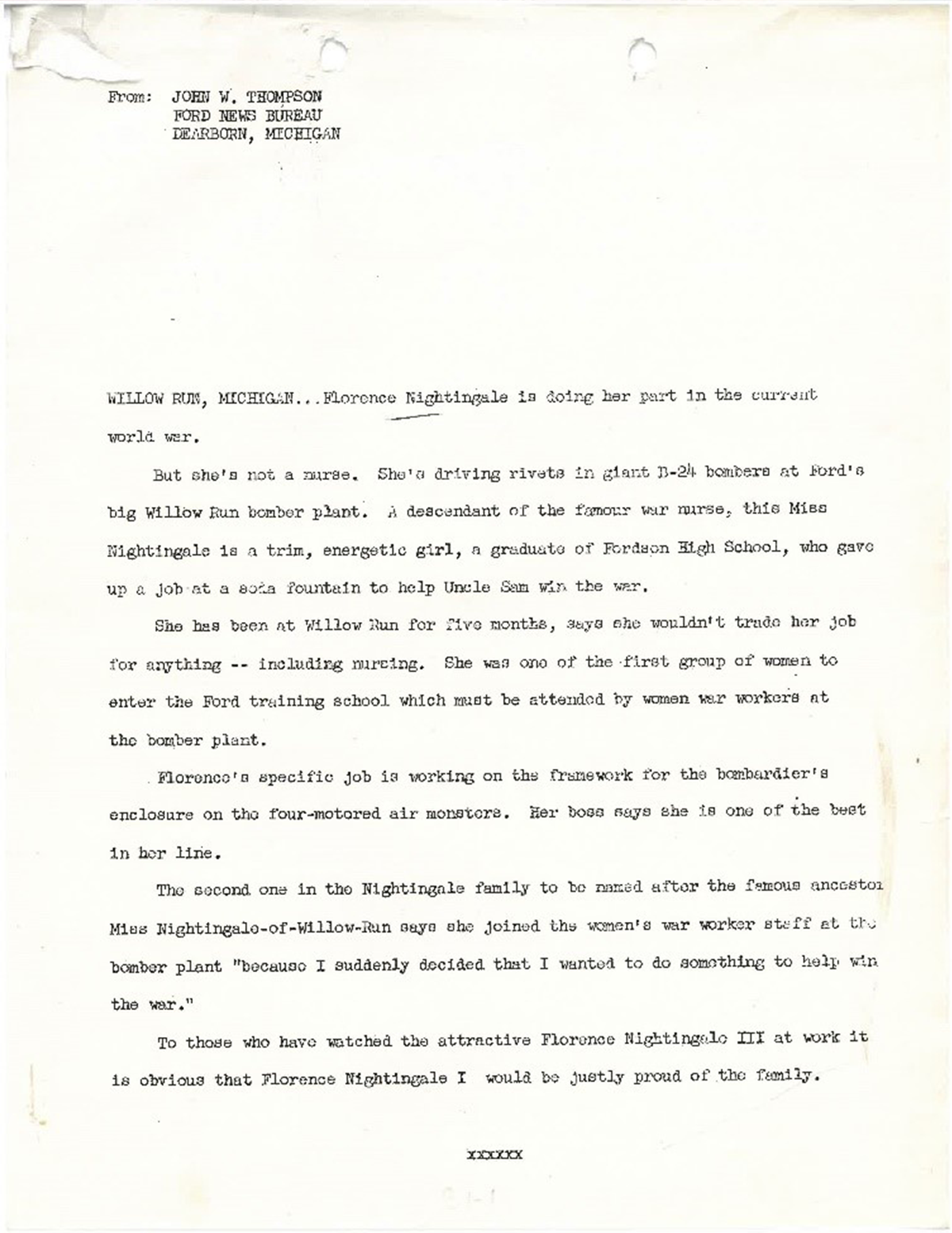

Stories of real-life Rosies proved helpful in motivating others to find their place in Ford factories. These stories, documented by the Ford Motor Company Photographic Department, were distributed across the country to news publications large and small.

Riveter Florence Nightingale Working at Willow Run Bomber Plant, 1942. / THF93712

Florence Nightingale III Press Release, 1942. Accession 378, Box 30.

The story of Florence Nightingale III, descendant of the famous war nurse, was distributed locally and meant to recall the long-standing tradition of women’s contributions during wartime.

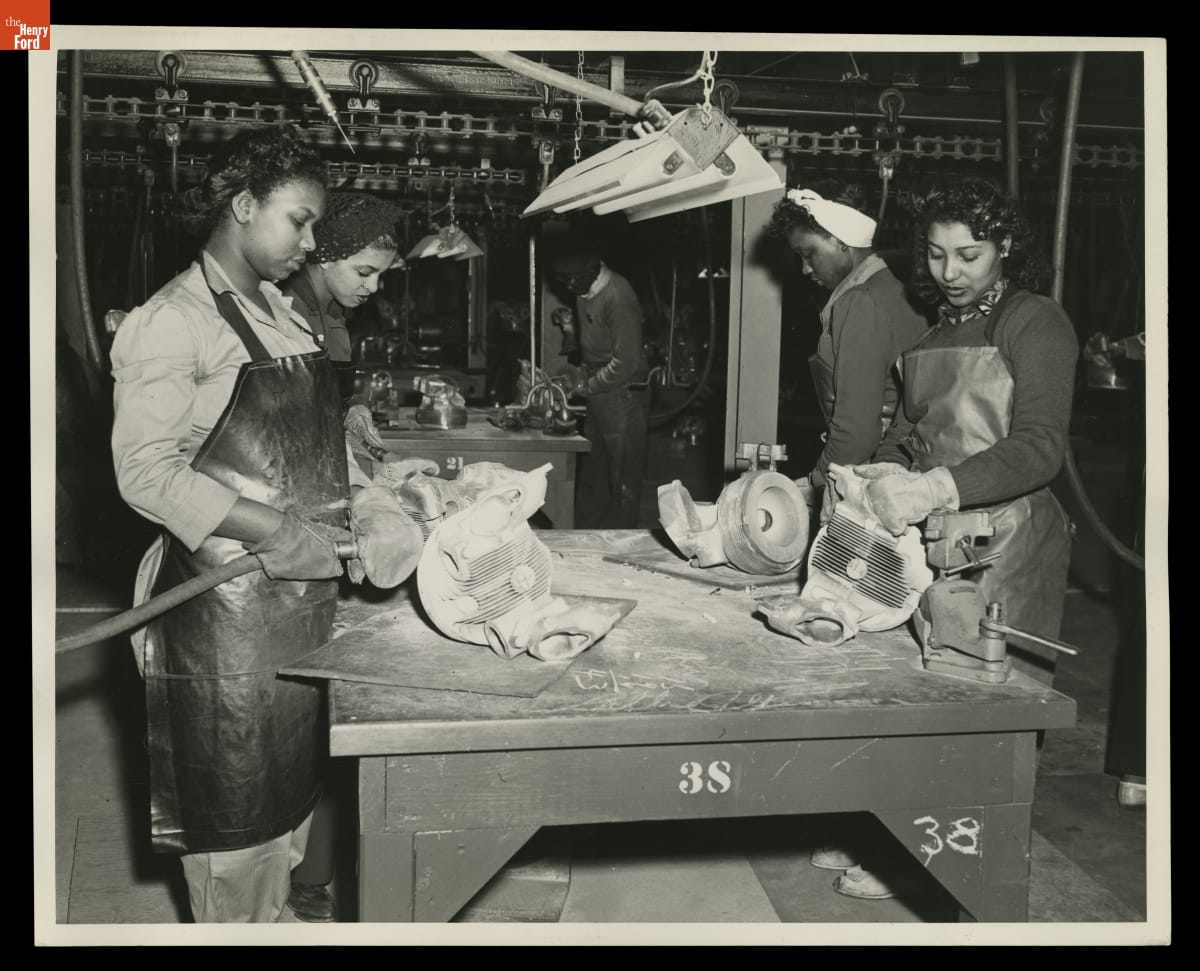

Women Making Sandcore Molds for Casting Cylinder Heads for Airplane Engines at the Ford Motor Company Rouge Plant, March 29, 1943. / THF82800

Women Making Sandcore Molds for Casting Pratt & Whitney Airplane Engine Cylinder Heads, Ford Rouge Plant, March 1943. / THF718497

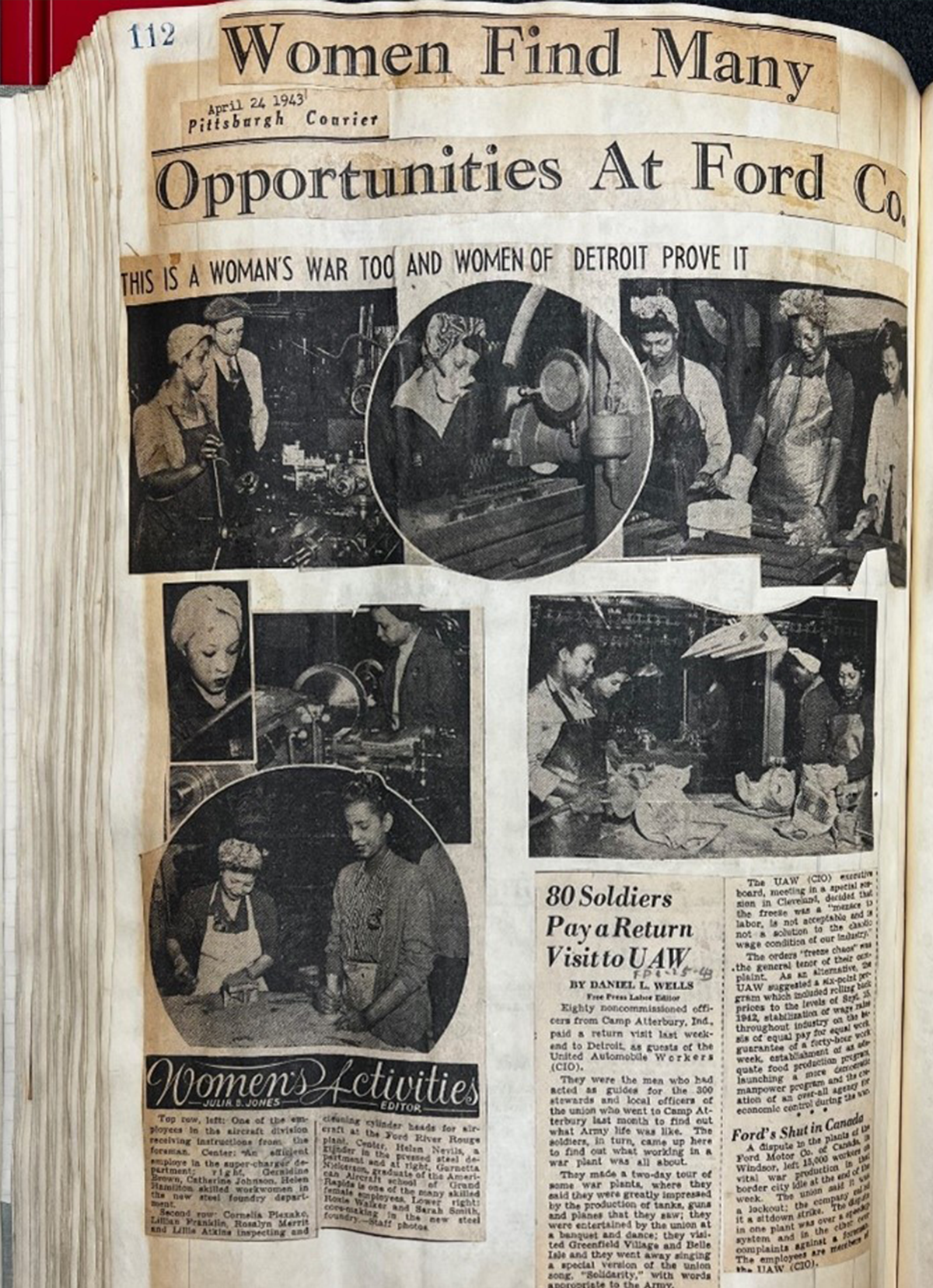

“Women Find Many Opportunities at Ford Co.,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 24, 1943. / Accession 7 Clipping Books Series, 1943.

A story on the women working at Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant was shared in the Pittsburgh Courier, highlighting the variety of jobs available to women and praising their skilled contributions to the war effort. Stories like this sought to encourage women to find work at Ford Motor Company and inspire efforts locally.

Norma Denton Using the Time Clock at Willow Run Bomber Plant, 1943. / THF23643

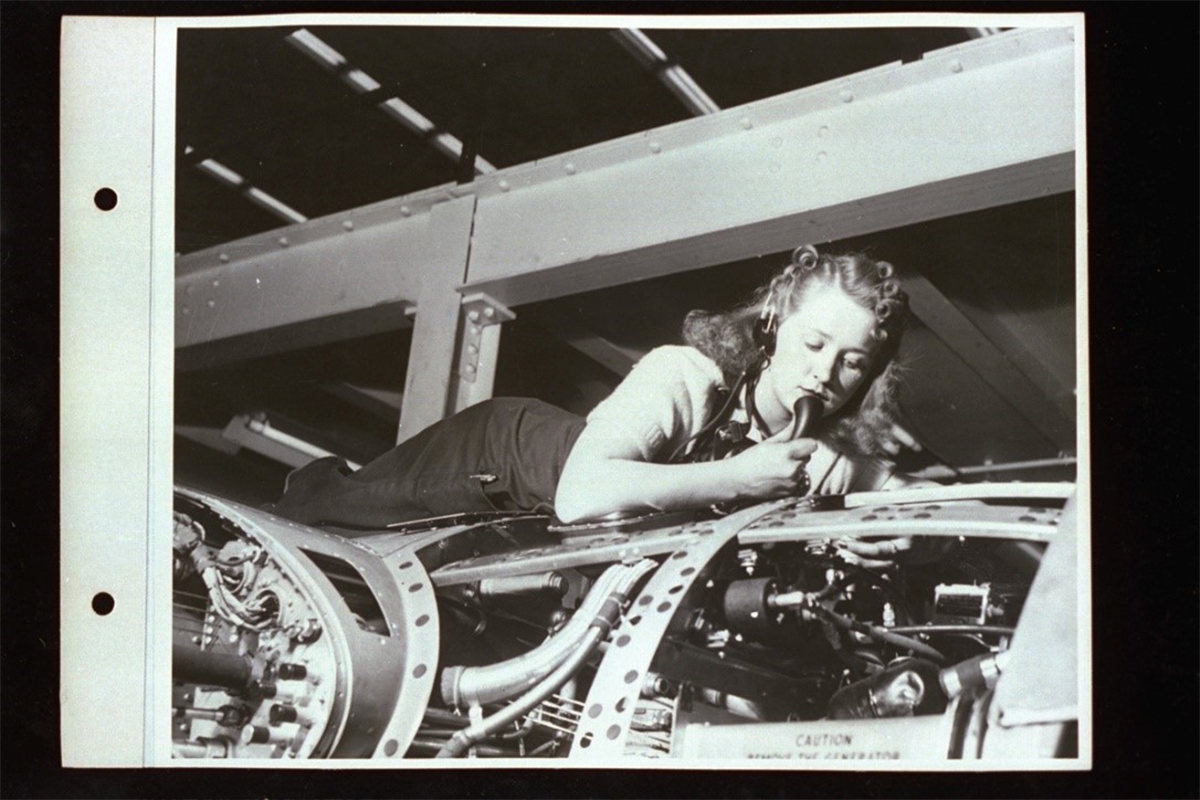

Norma Denton Atop an Airplane Assembly, February 1943. / THF326852

Norma Denton, a recent graduate, was featured in LOOK magazine, a popular and nationally distributed publication. Through a photo diary of her workday, part of a series titled Around the Clock Activities, Norma was photographed working, socializing, and enjoying the amenities of Ford Motor Company’s Willow Run plant. Her story aided in making wartime work more approachable and appealing to younger women.

While these special features brought some success, workforce demands persisted and required other innovative ways to draw the number of women workers needed to win the war. Following a visit to Ford’s facilities — likely related to research for his own wartime films — Walt Disney offered some creative suggestions to aid recruitment.

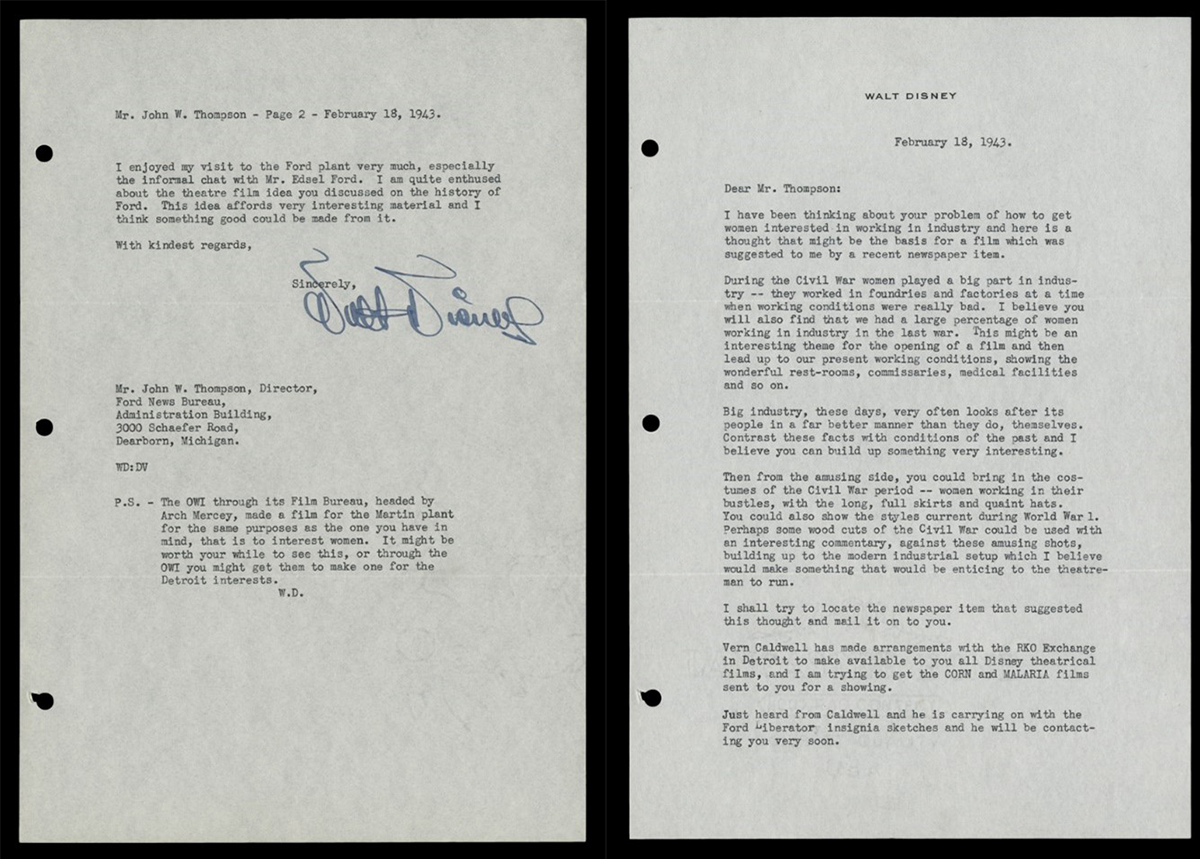

On February 18, 1943, Walt Disney wrote to John W. Thompson, Director of the Ford News Bureau, regarding an idea for a “Womanpower” movie. In his letter, Disney proposed a potential film aimed at attracting women to the factories by emphasizing women’s past contributions during wartime and highlighting the amenities offered to a modern industrial woman. Disney notes how much he enjoyed his visit to the Ford plant and his informal chat with Edsel Ford.

Letter from Walt Disney regarding Making a Ford Motor Company War Work for Women Film, February 18, 1943. / THF131114, THF131115

Edsel seemed to agree with Disney’s suggestion. In a memo from March 1943, he notes that in addition to regular press releases and housing improvements for women employees, a film is in production highlighting women working at Willow Run on aircraft assembly.

The ten-minute film, Women on the Warpath, aimed to inspire the next wave of women workers by recognizing the “American women everywhere, whose valor on the industrial front has sped the day of victory.” Previously, most women workers were young women or those who had traded traditional roles for higher paying factory jobs. The film makes an appeal to all women, including mothers and wives, that they are needed in the factories to help bring victory and their loved one's home. The film was distributed across the country with screenings in theaters and by a variety of women's clubs.

"Women on the Warpath," 1943. / Courtesy of the Ford Motor Company Collection and National Archives at College Park - Motion Pictures.

Ford Motor Company's efforts to recruit women workers proved victorious. During peak production, more than a third of their employees were women. As the war ended and men returned home to their jobs, many women returned to domestic roles seeing their work as a temporary patriotic contribution to help win the war. Others felt liberated from societal expectations and found a new sense of personal and economic freedom through working. It would take time before women represented a significant portion of the workforce in the same way, but the foundation had been laid for a more empowered and promising future.

Lauren Brady is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford

The Alchemy of Empathy

Experiential opportunities in cultural spaces can nourish emotional connections

By Elif M. Gokcigdem, Ph.D.

To challenge behaviors that contribute to fragmentation in our communities, we need more than an intellectual understanding of our interconnectedness. Besides knowledge, we need a deeper connection that makes us care and act compassionately toward the whole to which we belong — all of humanity, our kin that we share our world with and our planet.

We perceive and experience this indivisible whole from our respective worldview, which is shaped by the narratives we grow up with, our physiology, culture, language and other factors. The way we view the world influences how we make meaning of ourselves as well as what we share our existence with — people, objects, ideas, nature. What we find meaningful and worthy of our love, in turn, influences our behavior and actions, shaping how we live.

Empathy, our inherent ability to perceive and imagine what it might feel like to be the other, challenges our habitual worldview. When we feel an emotional connection to others’ experiences, our worldview expands to include diverse narratives. Experiencing this capaciousness lets us develop a broader sense of self who is able to witness their own attitudes, choices and behavior within the wider context of a collective existence. Witnessing and articulating our unique perception empowers us with agency to notice our motivations and calibrate our actions.

As we face increasingly complex global challenges, it is essential to reflect upon what empathy means to the collective of which we all are an integral part. Cultural spaces — like museums — are critical resources for empathy-building. Informal learning platforms, they can expand our worldview, allow us to explore narratives different from our own and perceive ourselves and our actions not as separate and singular, but integral to the whole.

During the last decade, I have been immersed in a multifaceted exploration of empathy-building through museums, leading a multidisciplinary and international community to deepen our understanding of this ability to relate to others and their experiences, and how to innovate new tools that can position museums as incubators for further empathy-building.

As I observed how intentionality and collaboration across cultures, disciplines and sectors were essential to this effort, the Designing for Empathy® framework and ONE - Organization of Networks for Empathy were born. Designing for Empathy® is an evolving framework that considers a oneness mindset as a master perspective, inspiring how we might see the world around us and our place in it, while reminding us to calibrate and harmonize our attitudes and behavior toward the collective. Within this context, empathy-building is defined as an intentionally designed, transformative lived experience through an encounter with the other that leads to an understanding of the self — not merely as a dispensable part, but as essential to the whole.

Museums allow us to intentionally utilize them as readily available platforms for transformative experiences of empathy and contemplation, where each encounter can be an opportunity to develop a knowledge of our humanness and the filters through which we perceive the world. While empathy-building requires intentionality, it also demands the presence of conducive ingredients within the “alchemy of empathy: storytelling, experiences of awe and wonder, dialogue, experiential learning and contemplation. Each of these ingredients (which are further explained on the following pages) offers a portal into a deeper knowing due to the transformative qualities they are rooted in — curiosity, vulnerability, authenticity, sincerity, humility, courage and trust.

Ingredient: Storytelling

Through first-person accounts, powerful stories from the point of view of the cultures featured, authentic objects and factual information, museums can offer opportunities to bear witness and articulate past and current events, and imagine what it would feel like to be a part of another’s lived experience.

Example: Greensboro Woolworth Lunch Counter

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., invites visitors to immerse themselves in the powerful narratives of the segregated Greensboro Woolworth Lunch Counter interactive exhibition. As visitors take a seat at a modern interpretation of the 1960s diner, they can choose to learn about the Selma March, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Woolworth’s Sit-in. Surrounded by dynamic visual storytelling elements and authentic artifacts, participants are then presented with choices that test their willpower in the face of adversity as they are asked to think about how they would respond if faced with these situations.

Ingredient: Awe & Wonder

An extraordinary experience, something that is otherwise inaccessible in our daily lives, or the immediacy of a newly found perspective on something ordinary, can shift our entrenched perspectives and paradigms, allowing us to explore our capacity for expansion and transformation through vulnerability and contemplation.

Example: Unsupervised

New York MoMA’s historic acquisition of Refik Anadol’s AI-powered installation Unsupervised offers a captivating experience that challenges our sense of place, time and scale. It invites us to find solace within by immersing ourselves in something vast, generative and fluid in its simultaneous and ever-changing creative expression.

Ingredient: Dialogue

Learning to hold off judgment is essential to any meaningful dialogue. Cultural resources in museums can provide a wide spectrum of context, bringing people together for facilitated experiences of non-judgmental listening and dialogue. Proximity to another’s narration of a lived experience, combined with intentionality and undivided attention, create space for empathy and trust to flourish.

Example: A Collective Dialogue: Exploring Belonging through Art & Empathy

At this public workshop I facilitated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., we explored the themes of “othering and belonging,” utilizing Robert Motherwell’s massive Reconciliation Elegy as the context for an engaging collective dialogue using the Creative Tensions method. Within this method, movement is often used in situations that require perspective, creativity and idea generation. A facilitator presents participants with prompts and invites them to express their stance on the matter by moving to one side or the other of a predetermined area. As individuals are invited to explain their choices, others are free to change their positions by getting closer or farther away from what is being shared.

Ingredient: Experiential Learning

An encounter is required to create, track and unfoldan inner experience such as empathy or a perspective shift, where one can witness the self, the other and the greater context within which the experience is unfolding. Through experiencing, witnessing and articulation, one might develop the agency to take responsibility of habitual perspectives and biases at the point of their arising.

Example: Human Phenomena

San Francisco’s public learning lab, the Exploratorium, includes the Osher Gallery which focuses on Human Phenomena. Here, a variety of playful, yet thought-provoking experiences enable visitors to explore some of the world’s most pressing problems through the lens of human perception, behavior and social interactions.

At the Science of Sharing exhibit set, for example, visitors are presented with situations inviting an immediate response in the form of a choice expressed by a real-time, real-life action. This human experience of encountering a moment of choice then becomes the subject and the object of the experience, opening up possibilities for developing a knowledge of the self through articulation and contemplation.

Ingredient: Contemplation

Expanding our circle of empathy requires conscious awareness, meaning-making and reflection. Contemplation allows us to go beyond our first impression of what is apparent into a search for its meaning and essence. What we find meaningful, or meaningless, shapes who we become as it influences our behavior. Through contemplation, each encounter with the other becomes an opportunity to discover something new about the self, and ultimately to transcend the self within a wider context.

Example: Mandala Lab

New York’s Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art’s Mandala Lab is a traveling experience that centers on an ancient Tibetan mandala to invite deep reflection on the human condition. As participants witness their unique perception and behavior through a series of encounters, they also observe a wide variety of reactions expressed by others around them, inviting contemplation on individual perspectives and actions within the expanded context of our shared humanity.

Editor’s note: The Rubin Museum transitioned to a decentralized, global museum model in fall 2024, closing its 17th Street building in New York City. Today, the museum serves people across the world through traveling exhibitions and experiences, along with partnerships, collection sharing, resources for artists and scholars engaging with Himalayan art, and digital content.

——

Time for Self Reflection

A look at what The Henry Ford is doing to build empathy on its campus, through the lens of those doing the work

The Henry Ford Magazine asked a small collective of The Henry Ford’s team to reflect on the role museums can play in empathy-building and what they experience, contemplate and hope to accomplish on our very own campus to encourage visitors to explore their own sense of self and interconnectedness to others. Experts from varied disciplines were chosen to give readers multiple perspectives, from longtime curators and our leadership responsible for talent development and community engagement to our most analytical minds and new faces giving fresh takes on theatrical programming. For scope, we asked everyone to consider the same questions. Here are the questions and their responses.

Why is it vital for educational/entertainment venues such as a museum to build empathy into their “culture” — from their guest experiences and programming to their collections and physical spaces.

From your perspective, what is The Henry Ford doing right in terms of its empathetic interventions? Can you share your hopes for the future?

Empathy Through Insight

Jarell Brown

Director of Analytics & Business Intelligence (B.I.R.A),

Principal Innovator of Innovation Atlas

The Henry Ford

Building empathy into the culture of educational and entertainment venues like ours (The Henry Ford) is essential for fostering inclusive and trusting environments for our guests. Empathy allows us to connect with diverse audiences and communities by understanding their past and current experiences, and their needs and aspirations, so we can create environments and programming that resonate and empower their voices.

By prioritizing empathy and inclusivity, museums can make their programs and exhibits more accessible, sustainable and meaningful to all visitors, regardless of their background, abilities or how they engage with The Henry Ford. Leveraging admission programs, educational programming and entertainment events like our Salute to America, Hallowe’en and Holiday Nights through The Henry Ford’s Community Outreach Program, for example, creates accessible opportunities that address some of the unique challenges communities face when trying to visit.

The Invention Convention Worldwide program, which leverages data and insights from the geographic information system Innovation Atlas, identifies schools, communities and regions for participation in learning how to invent, regardless of their socioeconomic background. Invention Convention Worldwide, like other accessibility programs across our organization, levels the playing field and inspires the next generation of innovators.

By fostering and practicing a culture of empathy within your programs and mission, museums can play a vital role in addressing and supporting unique solutions to the challenges communities face, breaking down barriers and inspiring the next generation.

Empathy Through Exhibitions

Jeanine Head Miller

Curator of Domestic Life

The Henry Ford

Museums are more than places that provide information — they offer opportunities to explore new experiences and be introduced to perspectives that are not our own. As thought-provoking places, museums have an important role in nurturing empathy.

Museums provide unique, often immersive, experiences as guests stand in the presence of intriguing objects while learning their stories, or enter spaces inhabited by people long ago. There is an immediacy, a visceral quality, to this multisensory experience that conveys deeper understanding of others’ lived reality.

Museum guests feel welcome when they “see themselves” in museum exhibits. By including stories of diversity, museums embrace underserved audiences and allow all guests to see the world through others’ eyes.

The Henry Ford has expanded the stories that it tells, moving beyond a traditional lens of white, middle-class experience to encompass a more inclusive vision. Our permanent exhibits are now planned with diverse viewpoints at the center of the conversation. Recent pop-up exhibits have shared the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community, explored more deeply the African American struggle for civil rights, and presented diverse December holiday traditions beyond Christmas.

We continue to gather an increasingly diverse range of objects and archival materials that represent more broadly the American experience, reflecting differing experiences and multiple perspectives of others who share our complex world. When possible, we also capture the reminiscences of those who used the objects, preserving layers of context and personal meaning — “voices” that will continue to foster deeper understanding for guests far into the future.

The ability to see the world as others do — and use it to guide our actions — is key to creating a kinder, more just world. My hope is that museums will continue to play a significant role in cultivating empathy, creating deeper, lasting understanding that encourages a worldview that values everyone.

Empathy Through Objects

Katherine White

Curator of Design

The Henry Ford

An 18th century German secretary desk sits at the edge of the Fully Furnished exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, surrounded by examples of mostly American-made furniture. A guest might easily stroll by the desk on their way to the shiny Dymaxion House or a new temporary exhibition in The Gallery, especially if the guest is not a furniture enthusiast. But like most objects in the museum, the desk is not as straightforward as a cursory glance suggests.

A closer look at the desk (or rather, the label nearby) reveals an incredible story of the desk and its owners, their persecution and survival as a Jewish family in Nazi Germany, and the family’s journey to America with all their belongings — including this heirloom desk.

This object, like all others in the museum, is really about people.

Museums are about people. The objects exhibited within them were created by people. People used these objects, invented them, selected them, cherished them, passed them down to their children, or perhaps sold them at a garage sale. Objects are powerful — they embody the stories of people. Objects have the power to transport us to another’s perspective and in doing so, create empathy for others both like and unlike us.

Museums are one of few public institutions that the public continues to find trustworthy. We have an incredible opportunity to cultivate empathy in the public through acquiring and exhibiting objects that tell a variety of stories. How challenging it is to demonize a group of people when encountering an object that illustrates their humanity!

We continue to work toward acquiring a more inclusive and diverse collection of objects, which will then become the basis for more inclusive exhibitions, programs and experiences for our guests. In the not-so-distant future, I hope that every person can see themselves reflected within this museum — and that every person encounters a perspective different from theirs, too.

Empathy Through Outreach

Anita Davis

Program Manager, Community Outreach & Engagement

The Henry Ford

Museums have a tremendous opportunity to inspire, empower and uplift underrepresented and minoritized groups. Oftentimes the stories of these groups are marginalized to trauma and oppressive snippets of their history. It can be much harder for certain communities to find hope and inspiration when there isn’t a balancing of hardship with celebration or unjust with equity in the storytelling of their history. This oversight has the potential to lead to mistrust of cultural and educational institutions.

the flipside, by not providing a holistic view of a particular community’s history, those on the outside may come to a misinformed conclusion. By having balanced storytelling, society can show more compassion toward one another, draw on similarities while also celebrating the uniqueness of others.

Through The Henry Ford’s Community Outreach Program, we are intentional about sharing the mission and work of our community partners. Our partners represent a vast variety of service organizations that support communities with great need and little resources. By spotlighting these organizations, our various networks can find personal connections, be inspired and hopefully decide to get involved. It’s important for us to create an environment of empathy and not pity. Pity can position someone as superior and the other as inferior. We combat this by providing opportunities for resource sharing and collaboration between corporate partners, communities partners, donors and The Henry Ford staff. We have learned that collaboration and intentional engagement among networks can lead to shared compassion for the well-being of a particular community.

My hope for the future is that The Henry Ford continues to build toward creating a more honest, inspirational and welcoming environment for all communities represented in our collection. Given the nature of our institution and the position it holds, we have a huge responsibility to ensure that we don’t misrepresent the people whose stories have been historically minimized.

Henry Ford is such a unique experience. We can truly be that community conveyor that inspires other cultural institutions to rethink how they tell stories and engage with surrounding communities.

Empathy Through Leadership

Mike Moseley

Director of Leadership and Talent Development

The Henry Ford

I always tend to look at things from the perspective of what’s the responsibility of leaders. It’s my job. As the director of Leadership and Talent Development, I will tell you that empathy is a vital leadership quality that benefits both individuals and organizations. By understanding and connecting with others, empathetic leaders can create a positive and productive work environment, drive innovation and build strong relationships.

So, as that applies to our work as museum leaders, using the ability to understand and share feelings of others helps people connect to their history, heritage and the world around them. A leader who can deeply understand and connect with the diverse audiences they serve — both staff and The Henry Ford guests — is better equipped to create meaningful experiences and foster a sense of belonging that is necessary for authentic storytelling.

Museum leaders who act empathetically attract people from all walks of life, with varying backgrounds, interests and experiences. A leader who can empathize with these diverse audiences can better understand their needs, desires and perspectives. This understanding allows for the creation of exhibits and programs that resonate with a wider range of people.

Empathy fosters trust and connection between leaders and their staff, volunteers and community members. When people feel understood and valued, they are more likely to be engaged and supportive of our institution’s mission.

The Henry Ford should be a welcoming and inclusive environment for all. We are continuing to work on that.

By empathizing with the experiences of marginalized communities, our leaders can ensure that our collections, exhibits and programs are representative and respectful of diverse perspectives.

The world is constantly evolving, and we must adapt to stay relevant. Empathy helps leaders to anticipate and respond to changing needs and preferences, ensuring that The Henry Ford remains a valuable resource for the community.

believe the ongoing commitment we have to strong leadership development at every level, and the institution’s commitment to creating a safe and diverse work environment, are steps that we are taking to build a more empathetic culture.

Empathy Through Performance

X. Alexander Durden

Manager, Theatrical & Musical Experiences

The Henry Ford

I have always wanted to push limits. Take things that I have learned from my life experiences and apply them in a different context. It’s what has opened my artist worldview.

Early in my hiring process in 2023, I asked about what programming we had on the African American community, Native Americans or the Middle Eastern population. For me, The Henry Ford provides an incubator where we can explore and talk about the stories and the people and be inventive about the ways in which we do it.

Last January, we premiered The Beginnings of the Boycott, a piece about the events that led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in the museum. We also debuted Market Season in Greenfield Village last year. Both are multicharacter pieces.

I noticed early in my time that a lot of dramatic programming was a single actor speaking first-person to the audience. Many times, we like watching a movie or attending a play because we have the opportunity to peek into a situation and observe, we get to pick up on the in-between, the nuances of the characters and the way they communicate with one another.

With Market Season, for example, we researched the historic multiculturalism of Detroit and focused on three Detroit Central Market figures in the late 19th century: market staple Mary Judge, Jewish fishmonger and activist Itzak Danto and James Kanada, the first Black frontiersman. We felt it was important to uplift these pillars in our local history by telling their connected stories.

Visitors often respond, “Oh! I didn’t know this person was real.” We are starting conversations, which is important because we want people to know these individuals beyond their biographies. We want guests to see how they existed together and the subtext to the relationships now on display. Visitors are definitely picking up on it.

Beyond dramatic programming, we have established our new performance series in the museum and village. Music in the Market and Arts & Artifacts highlight different musical acts, often based on designations like Jewish Heritage Month or Hispanic Heritage Month.

Not only are people being entertained, but they are also learning, being exposed to something new. That’s powerful because although our communities are quite diverse in the metro Detroit area, we don’t cross lines very often. We don’t ask questions. That’s why we’ve encouraged our guest artists to talk about their instruments, talk about their culture and the origins of their performances with guests.

Our job as a museum is not to preserve history but to provide context to history. Artifacts are only jumping-off points. We must talk about what and who led to innovation, what was the need that had to be met.

For hundreds of years, we have been interested in entertainment. We consume performances to feel what is an ideal or unideal human experience. We hunger for empathy or something we can empathize with. At The Henry Ford, I think we need to continue leaning into the uncomfortability. To appropriately contextualize history, we must talk about things that make us uncomfortable. How do we do that? Very carefully. Arts is a fantastic way to start conversation. Art speaks when words fail.

My hopes for the future... that we continue to activate other artifacts in our collections, find more common ground, and unearth and explore our differences because that allows usto understand the full range of humanity.

I am excited, thankful and hopeful that I can continue to contribute as much as I learn.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Agriculture in Hawaii: Pineapple

Pineapple cultivation in Hawaii confirms global movement of plants and people. The sweet tropical fruit (Ananas comosus) originated in South America. Then, Portuguese and Spanish colonizers transported the crop from the Western to the Eastern Hemisphere. Reputedly, the Spanish horticultural experimenter Francisco de Paula Marín moved the pineapple on to Hawaii in 1813.

Pineapple field in Hawaii around 1910 / THF200642

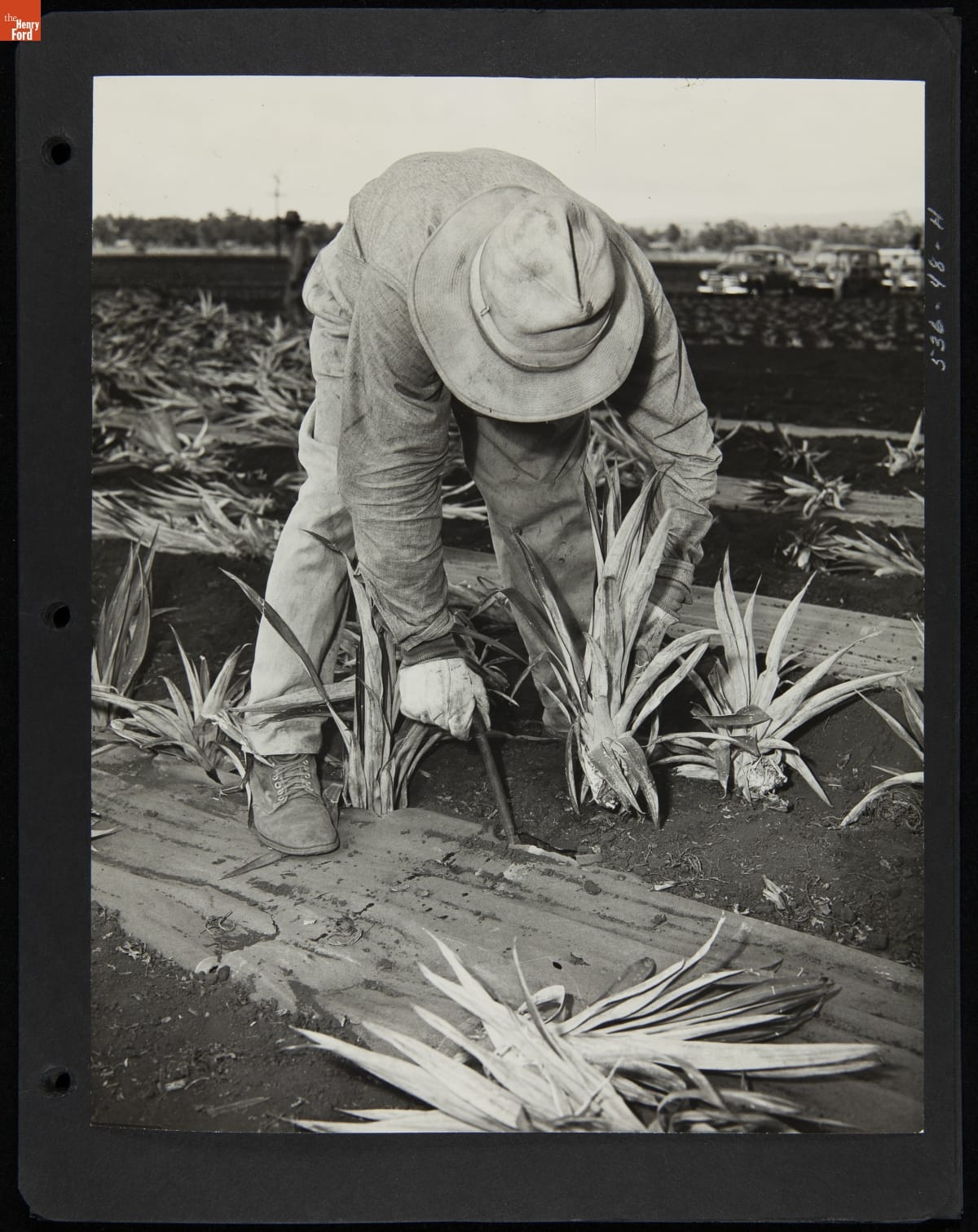

The pineapple transitioned from a novelty to a market crop slowly. First, planters focused on sugar cane, not pineapples, but changes in land and labor resources benefited growers of both crops. Namely, planters negotiated with Hawaiians for permission to recruit men from Asia, especially from Japan and China, to work on contract with native Hawaiians to raise cane and refine it into sugar. Ronald Takaki documented the experiences of these laborers as they created a working-man's culture on sugar cane plantations in Pau Hana: Plantation Life and Labor in Hawaii, 1835-1920. Hawaiians also abandoned traditional land-management practices that allowed planters to consolidate land.

Japanese and Chinese laborers worked along with Hawaiians at menial and management tasks as pineapple production increased. They prepared fields, transplanted the crop, and tended it over two years as it matured. They also constructed canning plants, harvested the crop for canning, and prepared shipping crates.

Some Japanese families farmed their own small pineapple fields. They performed field trials when John Kidwell, an Englishman who had relocated to California, began testing different types of pineapple. One, the Smooth Cayenne variety from Florida, appealed to planters for size and taste, and it became the standard crop grown in Hawaii.

Can label, "Gold Band Brand Sliced Hawaiian Pineapple," 1898-1930 / THF113853

Asian laborers remained at work in island fields after the United States annexed Hawaii in 1898 and incorporated the islands as a U.S. territory in 1900. Yet, U.S. immigration restrictions reduced the movement of Asian contract laborers onto the islands. Efforts to increase the number of white laborers and homesteaders in Hawaii never met expectations. Instead, planters continued to rely on short-term labor contracts to recruit temporary workers from the Philippines, or planters recruited laborers from other countries, namely Portugal and the Caribbean islands. These individuals could have acquired knowledge of the crop through previous experiences.

A pineapple field, southern Florida, 1904 / THF624691

A pineapple field, southern Florida, 1904 / THF624691

Schoolchildren might learn about pineapple cultivation from stereographs like this one, which shows the hard work of harvest in three dimensions. The image shows Black laborers in southern Florida wearing gloves and forearm coverings to protect them from the spiky leaves. The reverse of the stereograph explains the process of raising pineapples.

Harvesting Indian River pineapples in Florida, 1900-1910 / THF624683

Florida ranked as the center of fresh pineapple production in the United States around 1900, and additional fields in California and the West Indies supplemented the Florida crop. The stereograph shows and describes the process of harvesting pineapples for the fresh market. Laborers cut the fruit and handled it carefully to prevent bruising. The packers in the shed in the background (next to the water tank) laid the tender fruit in wooden packing crates to protect them during the trip to East Coast markets.

The canned pineapple business in Hawaii quickly outpaced the fresh fruit business closer to U.S. mainland markets. Years of engineering made the canning plants as mechanized as possible to reduce labor and ensure quality canned goods. A first step in the process required a machine that precisely cored the pineapple. James D. Dole, Hawaiian Pineapple Company, contracted with engineer Henry G. Ginaca in 1911. The Ginaca Pineapple Processing Machine resulted, patented, and further refined to increase the number of pineapples that could be peeled and cored in one minute. As John Wesley Coulter notes in his 1934 Economic Geography essay “Pineapple Industry in Hawaii,” it took less than five minutes to prepare one ton of fruit for canning.

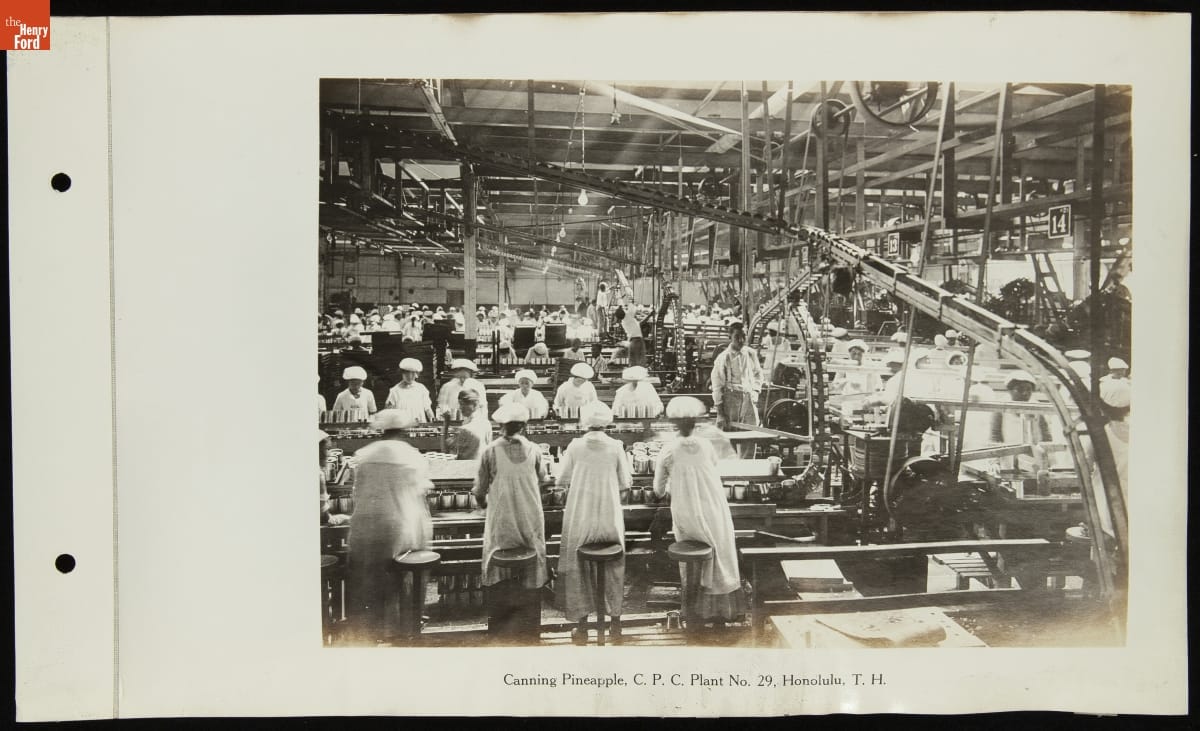

Packing pineapple, California Packing Company, Plant no. 29, Honolulu, circa 1922 / THF276827

As machines whirred, women sat on stools selecting “fancy” sliced pineapple and packing it into cans while others sorted and packed the standard grade. Others picked up irregular pieces for the lowest quality (and priced) can. Each line in the cannery kept a set number of women busy, and a man monitored the mechanics as depicted above in the photograph of Plant no. 29 in Honolulu.

“Fancy Quality” Royal Arms sliced Hawaiian pineapple, 1930-1939 / THF715748

A report on women working as wage laborers in seven Hawaiian canneries indicated that between the 1890s and 1920s, the total canned pineapple increased from 2,000 to 9 million cases. Women accomplished this work in clean and well-maintained factories, which were uniformly sanitary and modern according to Caroline Manning in her 1930 article for the U.S. Department of Labor Bulletin, "The Employment of Women in the Pineapple Canneries of Hawaii."

Women packing sliced pineapple into cans at the California Packing Corporation Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276640

Manning also reported that relatively few women — just over 14,000 — worked at wage-earning jobs in Hawaii, and most worked as agricultural laborers on sugar plantations. Of all wage-earning women in Hawaii, 65 percent were Japanese and 10 percent were Hawaiian or of Hawaiian descent. The remaining 25 percent were predominately women from Europe or the Americas working in clerical positions, with a few hundred women from China, the Philippines, and Korea employed in various wage-earning occupations. In canneries, women of Asian origin constituted 87 percent of the work force: Japanese (32 percent), Hawaiian (27 percent), Chinese (19 percent), Filipino (5 percent) and Korean (4 percent).

Women monitoring crushed pineapple. California Packing Corporation Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276667

Labor Bureau researchers confirmed about a dozen Japanese women working in the fields, usually alongside men in their families. The women removed crowns from the pineapples and packed them in crates for shipment to canneries. They also trimmed crowns, slips, and suckers in preparation for planting the next year's crop.

Laborers on these plantations sometimes secured lodging, water, electricity and fuel, medical treatment, garden space, and provisions available for purchase at a company store. Around 1950, the California Packing Corporation documented changes in Hawaii Pineapple Operations. One photograph shows children playing near worker housing covered with corrugated tin roofs.

Labor housing, California Packing Corporation, Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276665