Posts Tagged by debra a. reid

The Hearth is the Home

On July 14, 1948, Lois Kelley wrote "Dear Mother and Dad - Today is beginning clear, fresh, and cool, and I couldn't be happier because. . ."

Happy because of life on the farm with her husband, Bob, and their young son, Bobby.. Happy because of the way the place was responding to their nourishing touch. Happy because of the rabbits and peas and hay, and because "the baby is due in only five weeks."

In 1948, the Kelleys had settled on eleven acres in Rockville, Connecticut. The house, barn, hayfields, and berry patches all needed attention. The work and the record-breaking cold and snow of their first winter hadn’t chilled their enthusiasm for the future. They warmed to the learning and achievements ahead.

Kelley family farmhouse in Rockville, Connecticut, 1948. / THF723661

Kelley family farmhouse in Rockville, Connecticut, 1948. / THF723661

In the spring and summer of 1948, in her regular letters to her parents, Lois described learning how to plow a field, milk cows, harvest vegetables, and process meats. As the August birth of their daughter, Diana neared, Lois turned to indoor concerns like pie and shortcake, buying a freezer, making curtains, and increasingly, heating the house.

The Kelleys applied to add expenses for a new furnace to their mortgage. In July 1948, they received word that the request to add the furnace was denied. Undaunted, Lois reflected "all we have to do is ask ourselves whether we'd rather be in the apartment where there's heat and hot water, where dirt doesn't get tracked in, and weeds don't grow—and we feel absolutely blissful about this no matter what it lacks."

By October the Kelleys had a plan for winter. "We have another oil heater now - double burner living room type of a rather old vintage. . . so. . . we have our lovely stove in the kitchen, two double burner heaters (for living room and bathroom), and one single burner heater (for our bedroom). I don't see how we can help but be warm, even if this winter were to be as ferocious as the last. Just the same - I'm going to get Bobby some long-legged underwear - and some for myself too. (Red if possible.) Bob has a couple of sets from the Army.''

Detail from a letter from Lois Kelley to her parents, September 22, 1948, pg. 1. / THF723677

Detail from a letter from Lois Kelley to her parents, September 22, 1948, pg. 1. / THF723677

In February 1949, as the winter bore on, Bob intoned his favorite weather saying: "When the days begin to lengthen, the cold begins to strengthen." The Kelleys layered the home in curtains, storm windows, and insulation, and began to discuss central heat and hot water in earnest.

Bob Kelley removing his boots near the heating stove in the Kelley house kitchen, Rockville, Connecticut, 1948. / THF723649

Bob Kelley removing his boots near the heating stove in the Kelley house kitchen, Rockville, Connecticut, 1948. / THF723649

Over the winter of 1948-49 the family's finances improved. Thus, the bank approved their furnace loan in late August 1949, but the Kelleys still needed approval from the Veterans Administration (VA) Loan Guaranty Service. Anticipating delays there, the Kelleys would rely on the fireplace, but first they had to repair the chimney. They decided to build a Heatilator—a steel-lined fireplace that circulated heated air.

There were surprises. Lois Kelley recounted these with humor in letters to her parents.

August 26: "Bob started tearing down the plaster around the old chimney, the wainscoting, and the wall where the fireplace is to go. . . After Bob had torn up a few boards and then fell through. . . the sub-flooring, we decided that we need a new floor as well as a new ceiling and walls. . ."

August 29: “We ripped up the remaining floorboards this morning before Bob went to work, and just to make it unanimous, I fell through up to my hip. . . he's busy here now, putting in new joists. . . . One of the old ones practically disintegrated under Bob’s touch yesterday, it was so rotten!

And the chimney!. . . When Bob started to take it down, it split in half and fell, one half falling through the upstairs hall ceiling, and the other half landing on top of the guest bed, clean sheets and all!” The VA assessor chose that moment to arrive for his inspection.

Charlie Magdefrau replacing floor joists in the Kelley house living room, Rockville, Connecticut, 1949. / THF723664

Charlie Magdefrau replacing floor joists in the Kelley house living room, Rockville, Connecticut, 1949. / THF723664

The fireplace was finished before winter. On October 16, the day after their first test fire, "Bob started a real blaze, took off his shoes and took up the paper."

But delays continued with the furnace, as Lois revealed in her regular letters to her parents. Two days after that cozy fireplace fire, they signed papers for the furnace loan, though it would be five more cold weeks before they heard from the contractor. On November 23 he apologized that the steel strike had delayed a few parts. Midway through December Lois bemoaned that they were "just about due to run out of our cordwood." On the previous Saturday morning, "when we got up there was a skim of ice in the toilet. . . We're really ready for baths!" she complained.

Finally, on December 20, 1949, she exclaimed, "Yes we have heat!" For the first time in over a year, the family could take hot baths or invite overnight guests. Their yearly Christmas card featured the Heatilator with its advertised "Fireplace Charm plus Room Wide Comfort."

Kelley family Christmas card featuring Bobby hanging his sister's stocking above the Heatilator, December 1949. / THF723655

Kelley family Christmas card featuring Bobby hanging his sister's stocking above the Heatilator, December 1949. / THF723655

Having secured some creature comforts at the farmhouse in Rockville, Connecticut, the Kelleys turned their ambitions toward a larger farm. In 1953 they purchased a house constructed in the 1750s, located on Bear Swamp Road in nearby Andover, Connecticut. When they applied for financing, their bank said that it wasn't their "policy to take houses so old or unmodernized." The realtor, who owned an old house himself, helped them find a banker who also liked old houses, and the papers were signed.

South side of the Kelley family home with ell and vegetable garden in the foreground (positioned where the sun shown most intently), Bear Swamp Road, Andover, Connecticut, 1953. / THF723673

South side of the Kelley family home with ell and vegetable garden in the foreground (positioned where the sun shown most intently), Bear Swamp Road, Andover, Connecticut, 1953. / THF723673

Lois described their new winter preparations in a note to her parents on August 24, 1953. "Since we weren't able to get a heating system from the money derived from the other house, we have bought instead a gas chain saw. We call it our heating system. . ." With no regrets for leaving the Rockville furnace behind, she added, "We may not be as warm this winter as we might be. . . but we are certainly going to have a lot more fun than a furnace and radiators ever gave anyone!"

Wood cutting often took a neighborly tone. "Sunday we went over to the Hetzels' for an eat-and-run breakfast. . . the men all came back to cut wood. . . in return for their day helping us cut wood, we would take Sunday and cut wood for them."

The Hetzel family visiting the Kelley family, Bear Swamp Road, Andover, Connecticut, 1953. / THF723667

The Hetzel family visiting the Kelley family, Bear Swamp Road, Andover, Connecticut, 1953. / THF723667

Life on Bear Swamp Road found the Kelleys shuttling between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. The fireplaces on the central chimney that originally heated the house had been “updated” with layers of brick and plaster. In a move that was typical of the Kelleys, not just resisting but reversing trends of modernization, they began to look behind the walls.

Lois explained in an August 1953 letter: "We worked up our nerve and started chipping away plaster on the long room wall to see how large the fireplace had originally been. It was going to be only a small piece of plaster but by now the whole wall is nearly uncovered…"

By the end of 1953 plaster removal revealed four fireplaces all vented by the central chimney. The Kelleys restored the original cooking hearth and ashlar stone firebox. They heated the house with two cast-iron box stoves, Fire King and Dudley, that burned nearly constantly. Each stove—with their names cast into their sides—seemed to have a personality. Dudley was the "Big Guy!" Eight-year-old Bobby kept the wood boxes filled but Bob emptied them as fast, stoking the stoves.

Bob Kelley maintaining the heating stove, Dudley, in the Kelley farmhouse, Andover, Connecticut, 1955. / THF723675

Bob Kelley maintaining the heating stove, Dudley, in the Kelley farmhouse, Andover, Connecticut, 1955. / THF723675

The combination of wood stoves and hearth kept the large farmhouse snug. As Lois explained in a letter dated December 21, 1953: "We were tickled with our stoves during the cold snap. At times, although 10-15° outside, it was almost uncomfortably warm in here."

To the Kelleys, the Rockville house with its 1950s conveniences could not compare with the 1750 farm at Bear Swamp Road. Wood heat and the stone hearth were the center of the home and the feature of their 1954 Christmas card, as well as the center of the Kelleys' growing interest in historic preservation which shaped the rest of their lives.

Christmas Card showing the restored fireplace, Andover, Connecticut, 1954. / THF723671

Christmas Card showing the restored fireplace, Andover, Connecticut, 1954. / THF723671

This article was written by Diana “Daisy” Kelley, Curatorial Research Volunteer, The Henry Ford, with Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment, The Henry Ford. The stories and pictures are from the Lois Kelley collection at The Henry Ford.

You can read more about the Kelley family in "Kids on the Farm" and about their stewardship of a sugar bush on their second farm as they supplemented their food supply and farm income in "Maple Trees and Family: A Long-Term Relationship."

Kids on the Farm: A Year in the Life 1948

Lois and Robert Kelley craved outdoor space and projects to absorb their enthusiasm for life. After World War II they married and invested wholeheartedly in farming, believing it could provide peace of mind and sustenance for the family, with income supplemented by outside work. They bought an 11-acre property in Rockville, Connecticut, and modeled their work on the popular “Have-More” Plan promoted by Ed and Carolyn Robinson of Noroton, Connecticut.

The “Have-More” Plan motto, “A Little Land—A Lot of Living,” captured the farm family’s enthusiasm. At some point, Lois Kelley wrote Ed and Carolyn Robinson, explaining that “Your plan was the inspiration that led us to buy an 11-acre Homestead, complete with cow and chickens. . . . The fact that there is so little work is continually amazing to us, but perhaps it's because we really enjoy doing it. We're an enthusiastic advertisement for your plan.” The Robinsons must have cherished that letter because it appeared in a special issue of Mother Earth News (1, no. 2, 1970) devoted to the 1940s back-to-the-land plan.

Aerial view of the Kelley farm adapted to a Christmas card / THF720527

Aerial view of the Kelley farm adapted to a Christmas card / THF720527

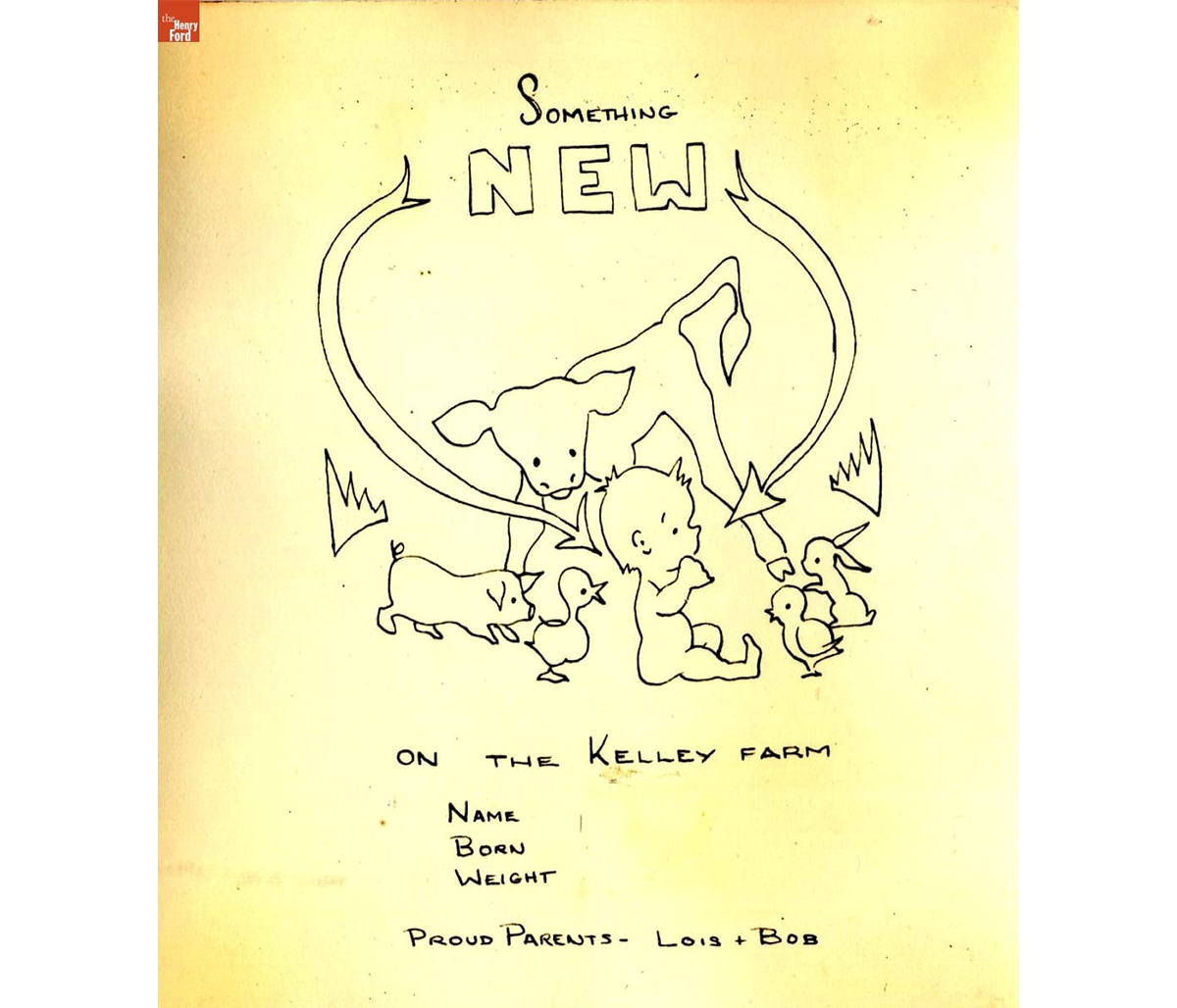

The Kelley farm included a house and barn, gardens, apple trees, hayfields, and berry patches, and after mid-1948, two children and dozens of farm animals. The birth announcement that Lois Kelley drew for Diane, her second child, shows the new baby with a calf, a piglet, a duckling, a bunny, and a chick. Lois rued the fact that, try as she might, she couldn't fit a goat kid into the picture.

D's birth announcement drawn by Lois Kelley 1948 / THF720614

D's birth announcement drawn by Lois Kelley 1948 / THF720614

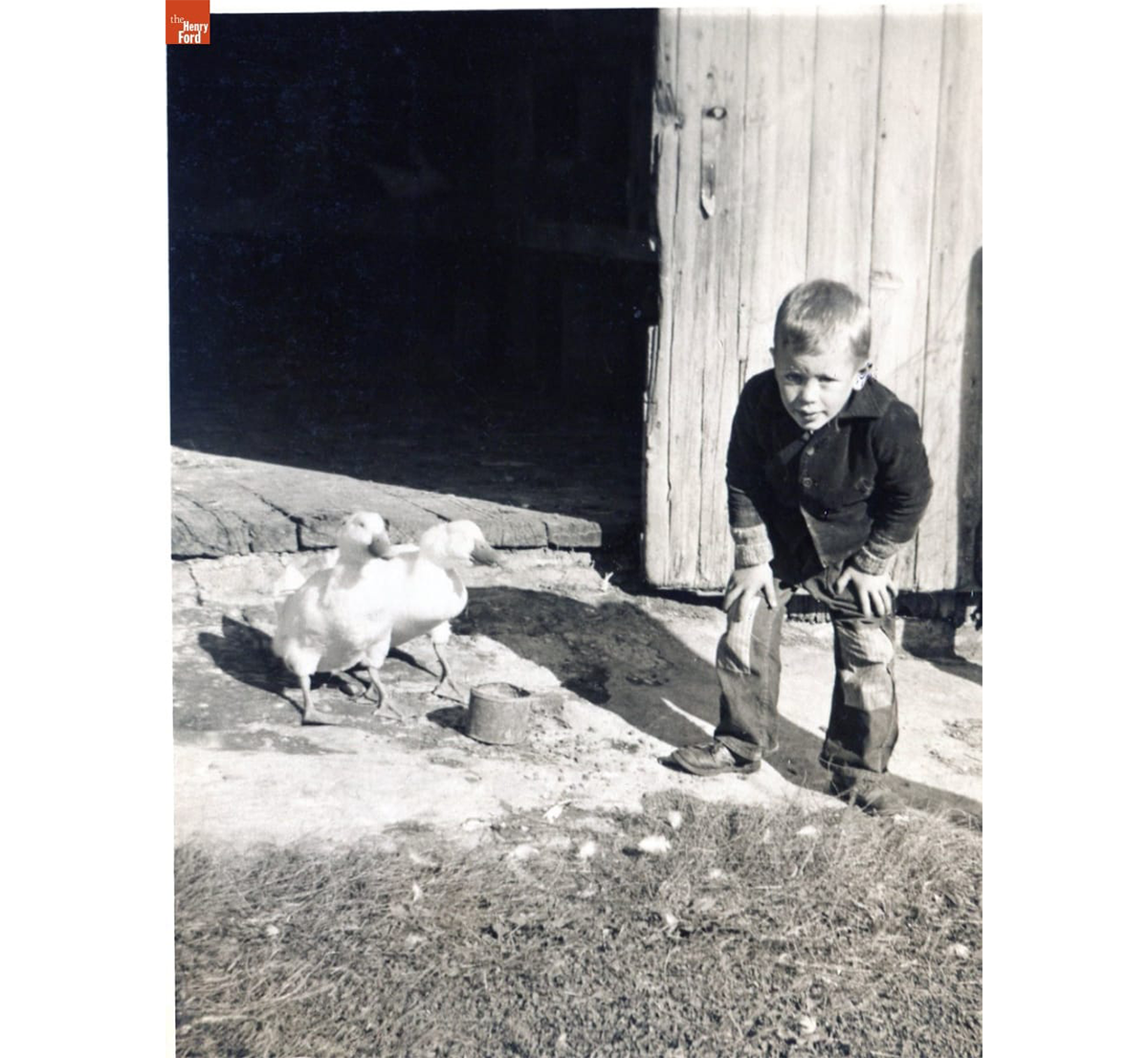

Diane and her brother Bobby grew up helping in the kitchen, barn, and garden. In a letter to her parents while she was pregnant with Diane, Lois wrote that her three-year-old son Bobby began doing chores. He fed the ducks and gathered eggs with her. The banty hens hid their nests in random places, to search out each morning as if it were Easter. A constant round of eggs incubated into ducklings, goslings, squab, and chicks in the cellar.

Bobby Kelley with ducks at the Kelley farm barn door, 1948 / THF720525

Bobby Kelley with ducks at the Kelley farm barn door, 1948 / THF720525

Each type of bird the Kelleys raised was hatched, fed, housed, and killed at the proper time, then prepared for the freezer or the table. Chickens, especially, fed the Kelley family all summer—broiled, fried, baked, or stewed. Lois wrote to her parents about a summer night when Bob surprised her by arriving home at midnight, bringing his sister and two of her children with him: “Lucky we'd planned on killing a chicken for Sunday dinner! The chicken killing was quite a process. The children watched . . . Bob tied its feet and hung it up instead of letting it flap all over, and later Judy, who's five, said to me, “You know, if Uncle Bob was going to cut my head off, he wouldn't have to tie my feet—I'd hold them still.”

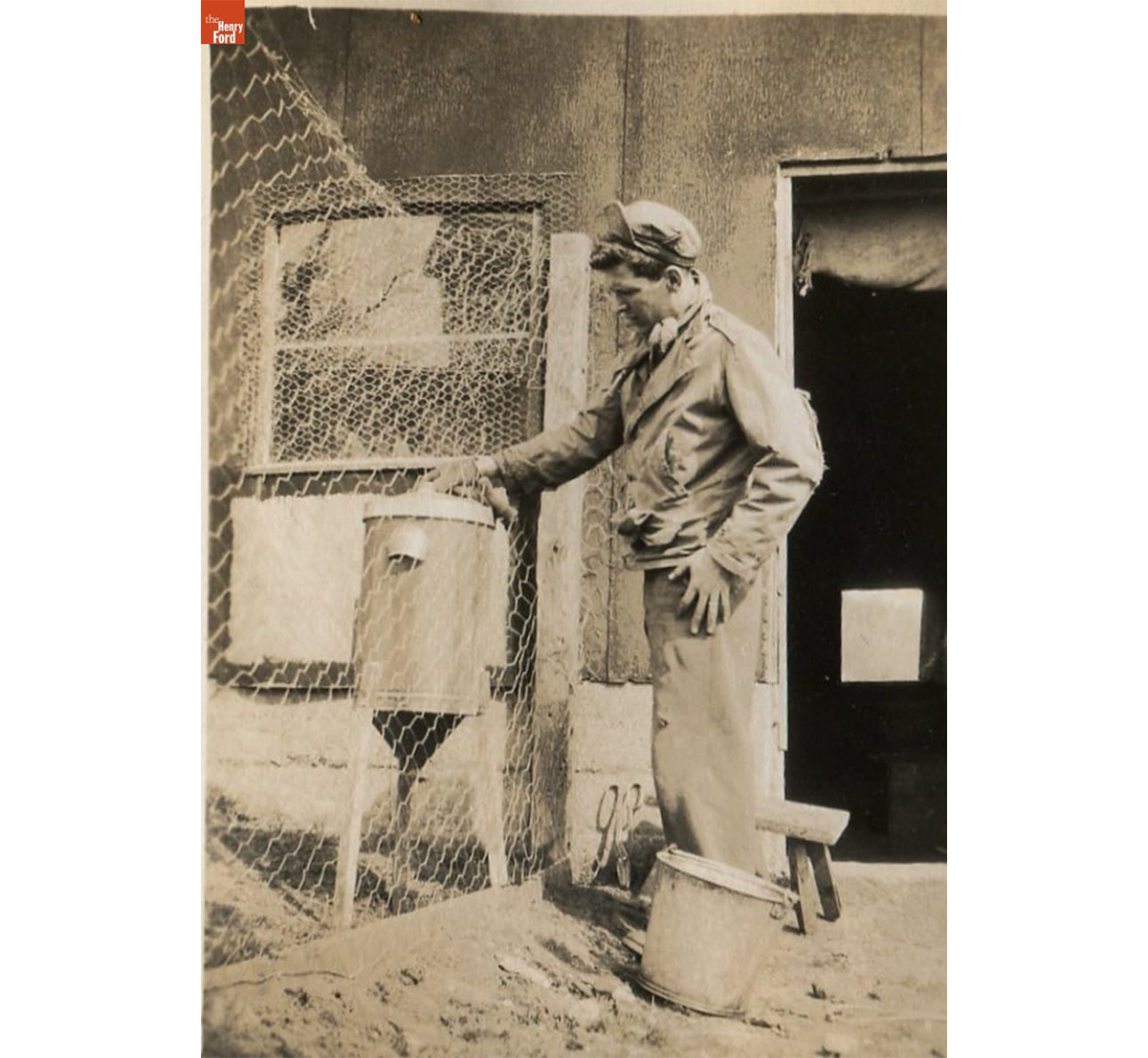

New chicken coop at the Kelley farm with feeder (likely a repurposed cream separator), 1948 / THF720526

New chicken coop at the Kelley farm with feeder (likely a repurposed cream separator), 1948 / THF720526

The "Have-More" plan made clear that farm families raised livestock to meet their food needs. The Kelley family all pitched in to raise their food supply on their little farm. This included fresh dairy products that Lois poured over berries to make rich desserts that she gloated over, and fresh milk served with eggs and bacon at breakfast. Cow's milk helped fatten the calves and piglets that the family raised throughout the summer. The Kelleys also enriched the garden soil with the organic fertilizer that the livestock generated. This ensured the summer's bounty of vegetables and fruit. Then, in the fall the family had the grown steers and pigs butchered, and they wrapped the meat and stored it in the freezer.

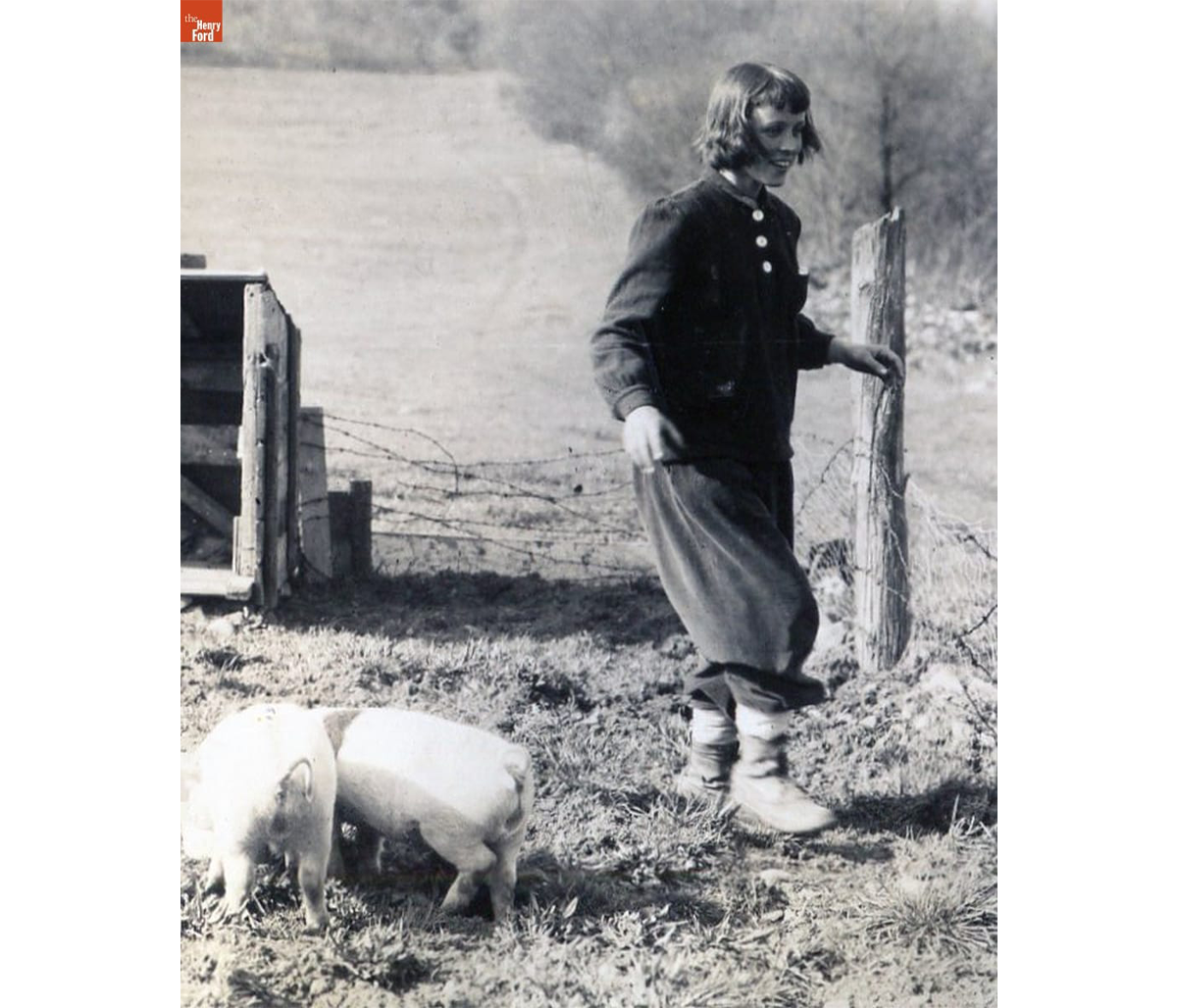

The process began with the arrival of piglets.

The Kelleys secured their first piglets in May 1948. Then, Lois wrote to her parents: “from Pig Heaven, May 3, 1948 . . . our biggest thrill is the pigs. They're well settled, little and white and cute—and one has a black spot and a blackish ear so we can tell them apart.” Bob built a pen with chicken wire and barbed wire, and a three-sided shelter of scrap wood. Lois was gratified that the piglets, though they previously had only nursed from their mother, knew exactly how to “eat like pigs.” She explained to her parents that “They began rooting like old-timers, and the battle they had over a pan of milk was something to see.” She hadn't expected that the pigs would inspire three-year-old Bobby to mimic them. “There he was,” Lois wrote, “on his hands and knees trying to root in the ground with his nose—his mouth full of dirt.”

Lois Kelley with the first piglets, 1948 / THF720528

Lois Kelley with the first piglets, 1948 / THF720528

Three weeks later, on May 24, Lois wrote that “The pigs seem to be at least twice the size they were ... Their hide is so tough by now that they don't respond to a good healthy slap, and if they had the least desire, they could be outside their pen in two minutes. . . . It was tough enough to catch them before, and now . . . it would be a job to keep hold.”

In June, barely a month after the piglets arrived, Lois's naivete over their cuteness was over. She explained in a letter to her parents that: “Yesterday the 'black 'pig got out once too often—he'll never do it again. Both nasty animals are now settled in the cellar of the barn where we said it was utter inhumanity to keep an animal. They brought it on themselves, however . . . They're getting awfully heavy to move .. It'll be a relief to the neighbors too, who have helped me catch this one on the several past occasions when it's rooted out.” On October 9, she wrote that feeding them had “become quite dangerous—not that they're ferocious, but they're so eager to be fed that they swing their weight around with a terrible disregard for any one else's rights. I've given up going in—just the noises they make behind that door are enough to terrify me.”

Kelley barn in a Snowstorm, 1948 / THF720523

Kelley barn in a Snowstorm, 1948 / THF720523

November 3rd six months from the day the “cute” piglets arrived, they met their fate as provisions for the freezer. Lois wrote that the butcher dispatched them with his .22, bled them, “then drove off with them in his truck to scald, scrape, disembowel and chill them at his place.”

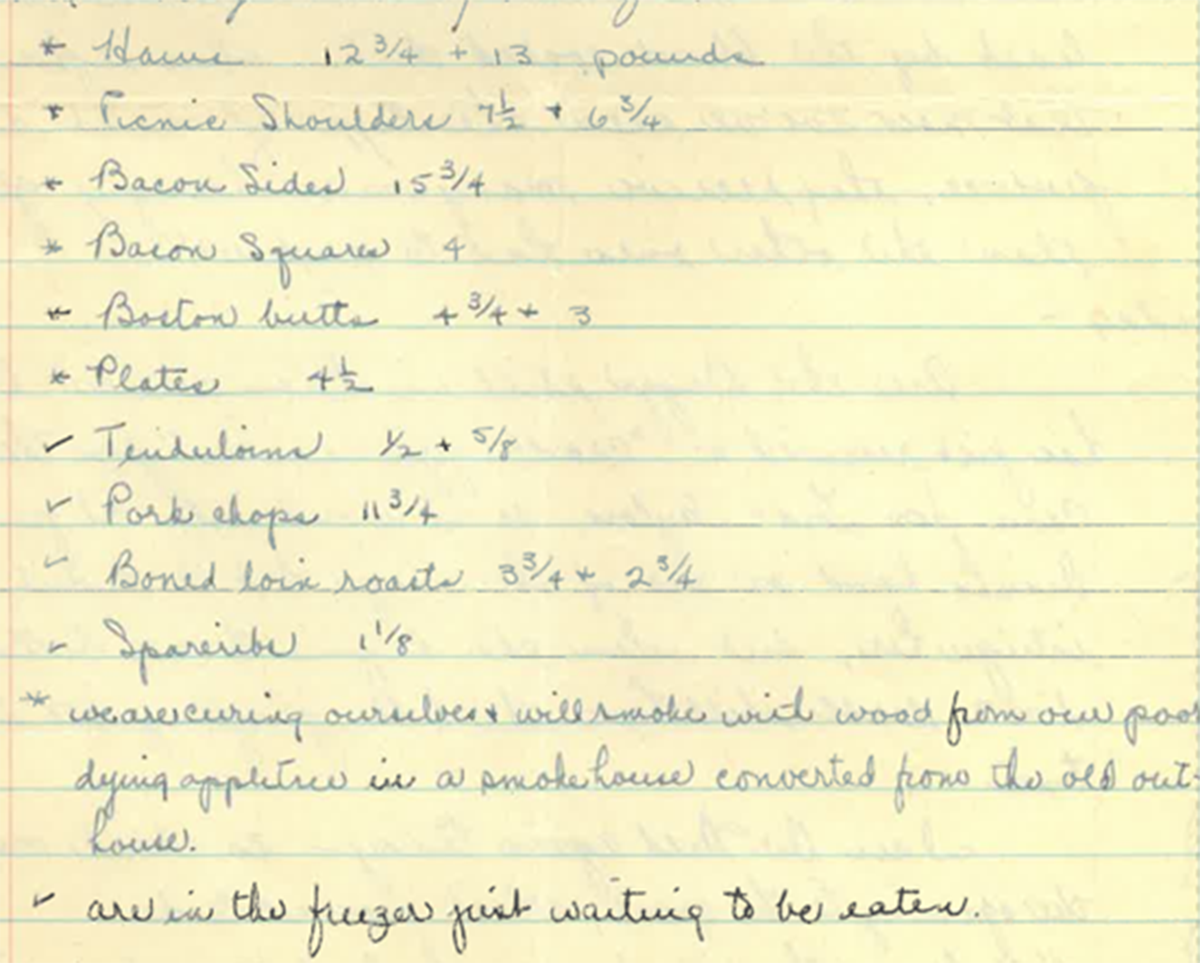

Lois and Bob cut and wrapped the meat from one of the pigs, weighing 154 pounds, and a neighbor took the other in trade for spring plowing. Together, they provided the following (plus sausage, head cheese and lard):

Detail from “Dear Mother and Dad” letter, November 3, 1948 p3. Image provided by Daisy Kelley.

Detail from “Dear Mother and Dad” letter, November 3, 1948 p3. Image provided by Daisy Kelley.

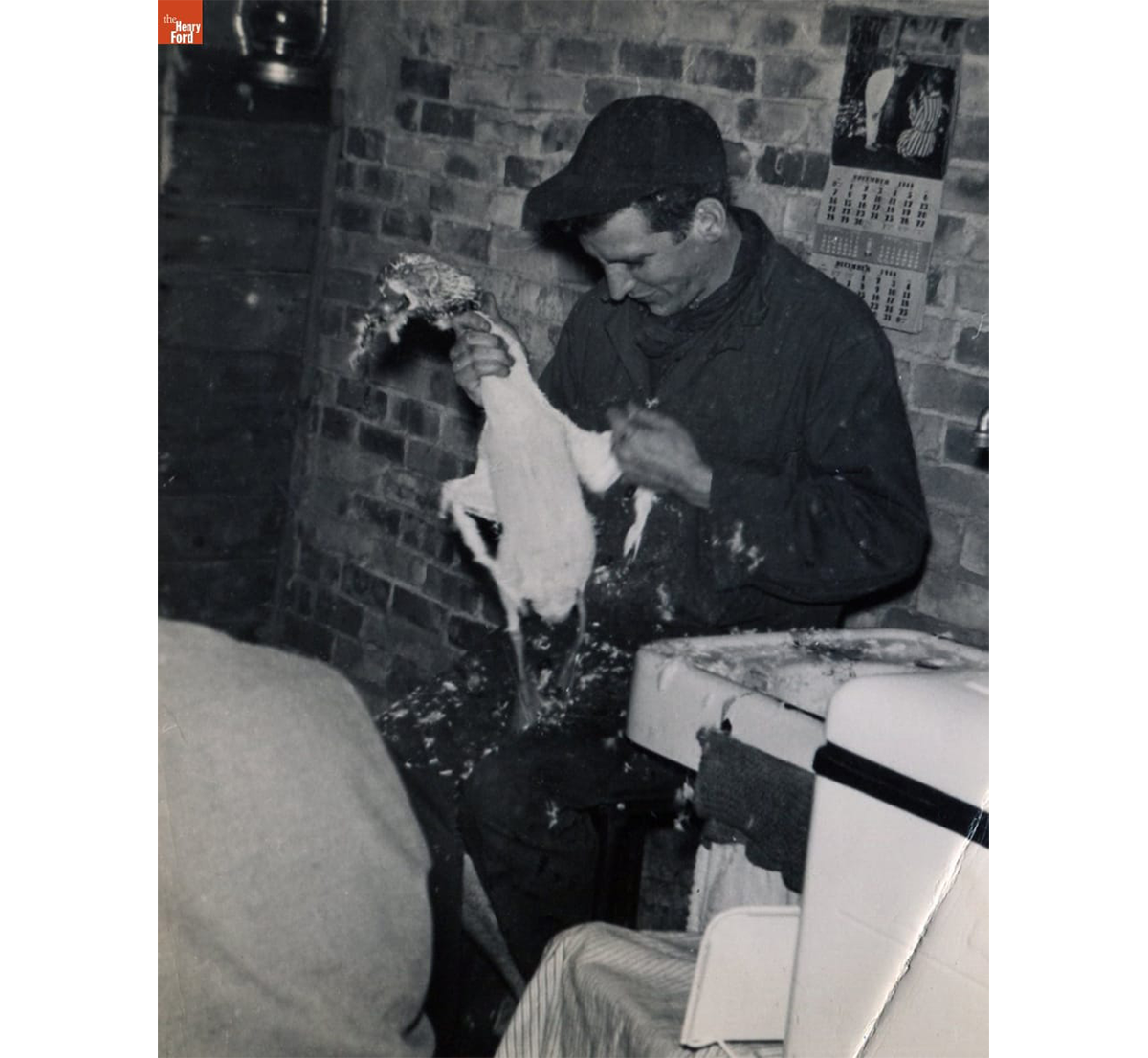

The Kelley family prized the food in the freezer year-round, but the larder took on special meaning for the holidays. In August Lois began dreaming of Thanksgiving dinner. Would she serve turkey, capon, duck, rabbit, or broiled or fried chicken? Corn on the cob, raspberry or strawberry shortcake, tons of vegetables, blueberries, squash, ice cream? Lois's letters tell that when the first Thanksgiving on the farm finally arrived, duck was served. They were the same ducks Bobby had fed daily as part of his chores. “We are proud,” Lois wrote, “that though Bobby took care of them from the time Bob brought them home, he was just as interested in the killing, plucking, and eating of them as the rest of us.”

Bob Kelley plucking a duck on the night before Thanksgiving, November 24, 1948 / THF720524

Bob Kelley plucking a duck on the night before Thanksgiving, November 24, 1948 / THF720524

On Christmas Day 1948, Lois and Bob took the first of the hams out of the freezer for dinner, a finale for that year’s pigs and for 1948, the family’s first year raising food on the farm.

This article was written by Diana “Daisy” Kelley, Curatorial Research Volunteer, The Henry Ford, with Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment, The Henry Ford. The stories and pictures are from the Lois Kelley collection at The Henry Ford.

You can read more about the Kelley family and their stewardship of a sugar bush on their second farm (another supplement to their food supply and their farm income) in the blog, "Maple Trees and Family: A Long-Term Relationship."

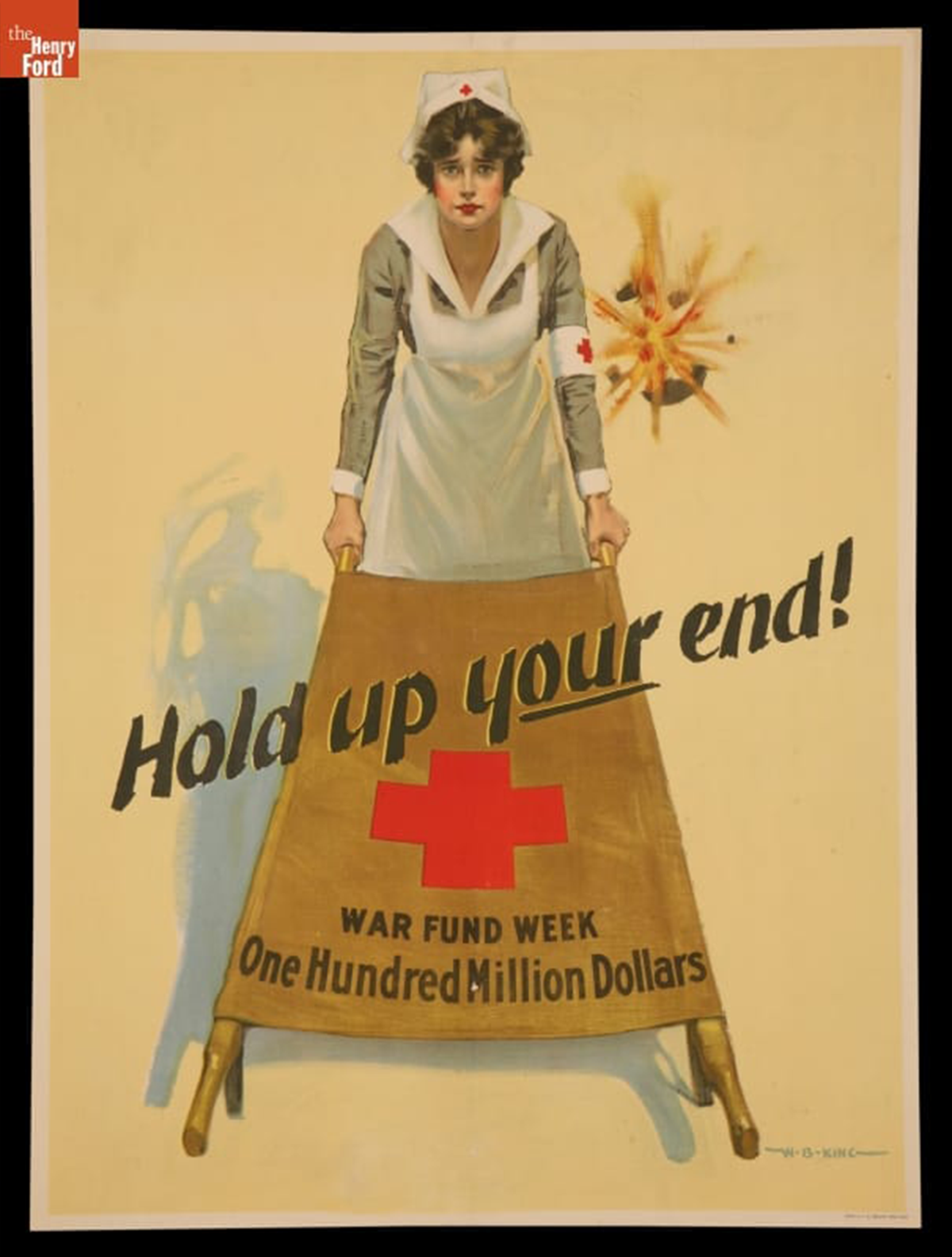

The following article shares highlights from the collections of The Henry Ford to illustrate work undertaken by female Red Cross volunteers during World War II. More than three million women repaired and drove vehicles as part of the motor corps, cared for wounded service members in military hospitals, operated blood banks or operated canteens overseas, among numerous other tasks. The collections included here can help us to understand the role of women in the American Red Cross during wartime.

Join American Red Cross poster, 1942. / THF289755

The poster above conveys the centrality of women to the U.S. military response during World War II. The Red Cross, a non-governmental organization, “always stands by as friend to the service man” (Redlands [California] Daily Facts, 12 November 1941). The illustrator, Robert C. Kauffmann, emphasized the Red Cross nurse in other colorful posters during this time—aimed at recruiting nurses, field directors and hospital recreation workers. Sometimes he contextualized the nurses’ work in domestic flood relief, sometimes in war relief, but always with the message to “join.”

Women’s Motor Corps

Comparable service during World War I set a precedent. The American Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps began in 1917 and included women volunteers who transported the sick and wounded in ambulances.

Red Cross training using Ford Model T ambulances at the Highland Park Plant, July 1918. / THF130013

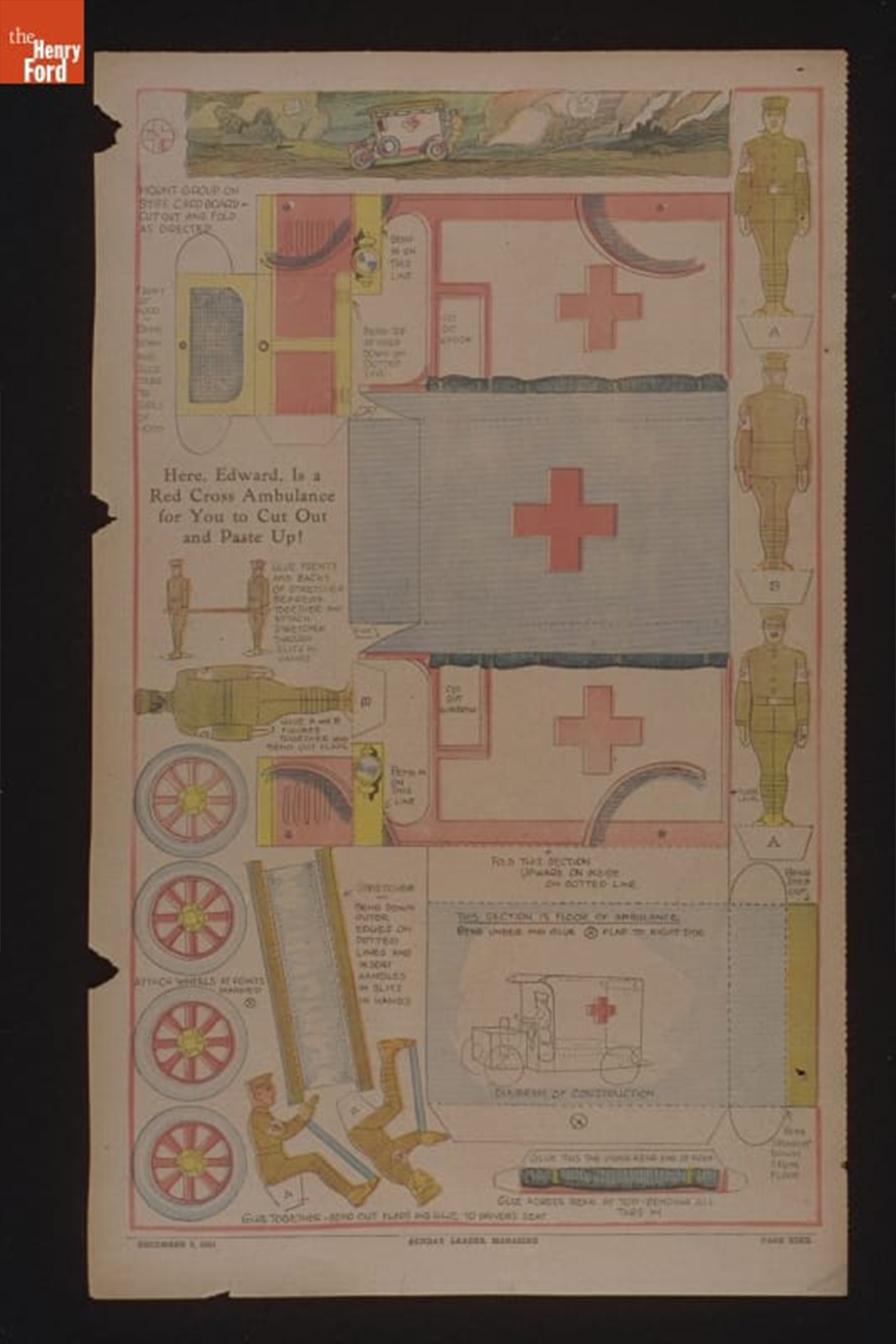

The American Red Cross, as a non-profit organization, depended on volunteers and charitable donations to meet need. During World War I, membership increased from 17,000 to over 30 million adults and older children. Contributions amounted to over $400 million in money and supplies. Ford Motor Company contributed $500,000 during the early years of World War I. The Red Cross turned around and used those funds to purchase Ford vehicles, nearly 1,000 of them, including 107 ambulances, for wartime use through the Motor Corps. Newspapers helped promote this work especially to young readers, as the following colorful cutout of a Ford ambulance represents.

World War I Red Cross Ambulance Cut-Out Paper Toy, December 9, 1917. / THF342142

Soon after war erupted in Europe in August 1939, urgent requests from the Red Cross began to reach wealthy Americans. Edsel Ford indicated his intention in May 1940 to support the fund drive required to meet the unprecedented need for assistance in war-torn Europe. He sent a postal telegram to W. J. Scripps of WWJ radio explaining that “Detroit’s share of the proposed relief fund can be raised only by the generous cooperation and support of everyone.”

Ford Motor Company maintained its support of the Women's Motor Corps during World War II as 45,000 drivers filled the Corps' ranks. This included African American chapters in some cities. The volunteers logged over 61 million miles ferrying Red Cross staff and supplies, couriering packages and messages, and occasionally assisting with Army and Navy transportation needs.

American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps members becoming familiar with engines during an auto maintenance class, Ford Motor Company, November 1941. / THF270093

Keeping the vehicles on the road required expertise. In 1941, Ford Motor Company began to provide automobile maintenance classes for the local Women’s Motor Corps at its Highland Park facilities. Instructors trained the volunteers in the mechanical skills they needed to keep their vehicles moving in times of emergency.

American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps members looking under the hood of a Ford ambulance, June 1942. / THF265816

Ford Motor Company donated its 29 millionth Ford automobile to the cause. The Super DeLuxe station wagon rolled off the Rouge Plant assembly line in April 1941. Edsel Ford presented this vehicle to the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross for use by the volunteers of the Women’s Motor Corps.

The 29 Millionth Ford and a driver from the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps, April 29, 1941. / THF270147

Workwear for Health Care

The American Red Cross hired trained nurses to assist doctors treating service men. Gray ladies nurse's aides provided an additional layer of volunteer support in military hospitals and boosted the morale of patients. They all wore the distinctive red cross emblem on their uniforms, adopted at the 1864 Geneva Convention to designate medical personnel during wartime. Active-duty Red Cross nurses wore plain white uniforms with bishop collars and caps and a dark blue cape lined in red during wartime, which was standard issue throughout World War II. As of December 24, 1915, active-duty nurses stationed abroad wore gray cotton crepe dresses with a white pique collar and cuffs, cap, and brassard. Public health nurses wore gray chambray. Uniform regulations decreed that the red cross appear prominently on the front of the cap, brassard, and nurse’s cape.

World War I era poster depicting the uniform of a Red Cross public health nurse, 1917. / THF112608

The Gray Lady Service also tended to soldiers in non-medical capacities during and between wars. They wrote letters, delivered bandages, or served snacks to men who needed physical and emotional comfort.

Gray Lady Service uniform, 1940-1945 (left). / THF173341; Gray Lady Service uniform, 1955 (right). / THF94383

The indoor uniform of the Gray Lady Service consisted of a gray cotton dress with detachable white collar and cuffs, a two-inch woven red cross on the upper pocket, and white epaulets worn on each shoulder. The red bars and chevrons worn on the sleeves conveyed length of service (Shirley Powers, “A Guide to American Red Cross Uniforms,” 2nd ed., 2006).

American Red Cross Volunteer Nurse's Aides, Peoria, Illinois, May 20, 1942. / THF289753

The American Red Cross and the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense specified details of the volunteer nurse’s aide uniform in November 1942. It consisted of a blue jumper-apron worn over a regulation white poplin blouse. Nurse’s aides donned the uniform after the first 34 hours of training, and the cap after completion of the 80-hour course. The full uniform included a three-inch joint Red Cross and Office of Civilian Defense nurse’s aide emblem, sewn on the upper left sleeve of the blouse, two inches below the shoulder seam. Chapters could recognize hours of service by awarding white stripes but only for those volunteering in hospital wards, in clinics, and in health agencies qualified for these.

National Blood Donor Service

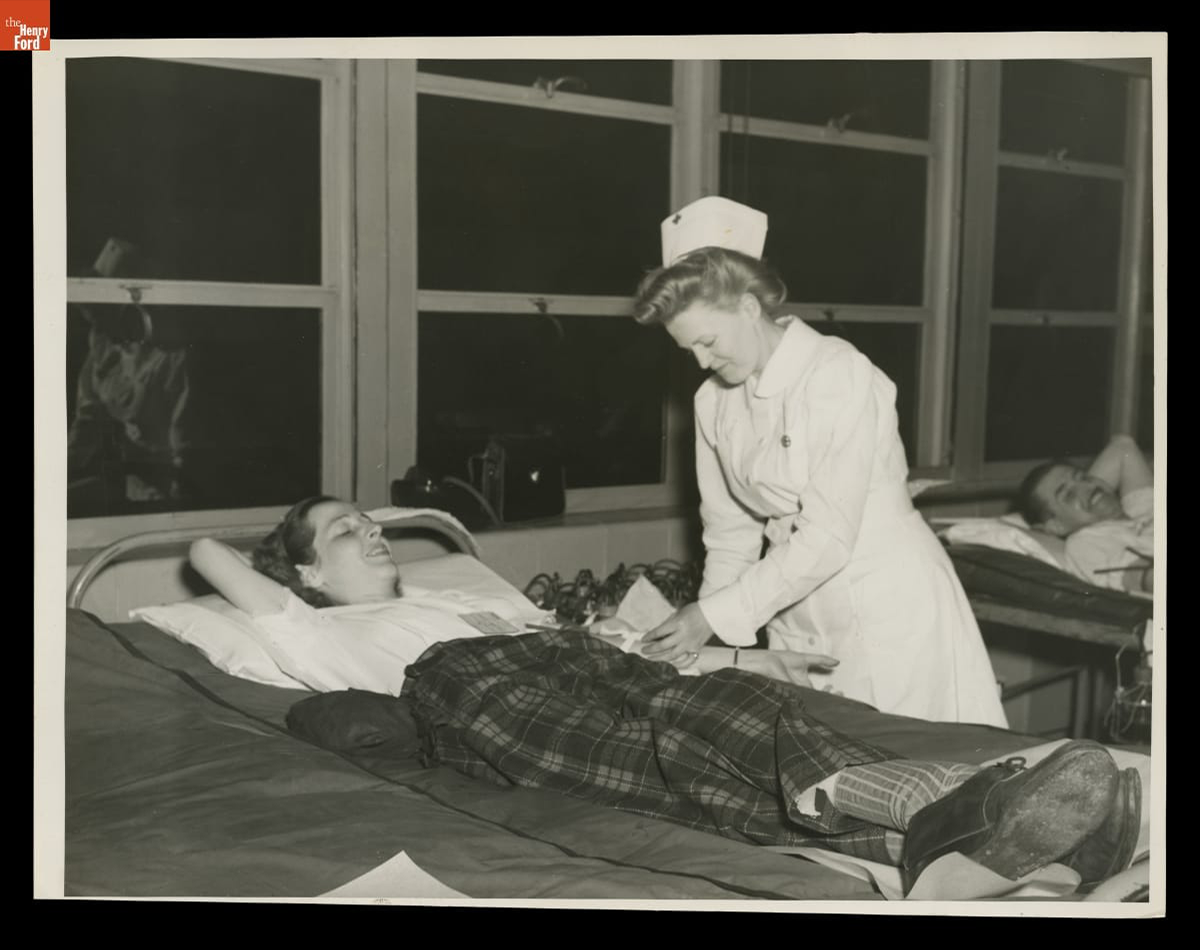

The American Red Cross began its National Blood Donor Service for the U.S. military in February 1941. Volunteers worked in the new blood banks, collecting blood and plasma donations and shipping them to hospitals caring for soldiers wounded in battle.

25,000th Blood Donor at the Ford Rouge Plant Pressed Steel Building, May 1943. / THF290075

Women working at Willow Run had their first chance to donate blood to the National Blood Donor Service in November 1944. The Ford Motor Company built its Willow Run Bomber Plant in 1941. Approximately one-third of the labor force were women. They performed office work but also drafted designs and worked on the assembly line, riveting and welding B-24 bomber components. At the plant's peak in 1944, Willow Run crews produced an average of one bomber every 63 minutes.

A Red Cross nurse draws blood from a female Ford Motor Company employee at Willow Run Bomber Plant, November 27, 1944. / THF728198

Canteen Girls and Donut Dollies

The female Red Cross volunteers who faced some of the most dangerous situations during World War II included those who served overseas as Canteen Girls or Donut Dollies. This work began during World War I in service to soldiers on the move, as a 1918 photograph of an African American woman in Detroit, handing bananas to soldiers indicates. During World War II, women traveled in mobile club wagons that often operated close to intense fighting. Critics claimed that the young women, all college educated and carefully selected, assumed significant personal risk. Julia Ramsey, author of “’Girls’ in Name Only” (Auburn University, 2011), claims that these women had access to battle and combat that no civilian women had previously. Paige Gulley, author of “After All, who takes care of the Red Cross’s morale?” (Chapman University, 2021), analyzed primary source created by the volunteers themselves to explain how women relied on each other to manage stress and meet expectations.

These examples represent the breadth of service and due diligence that female volunteers provided to the American Red Cross. The organization was not perfect and need often exceeded the capacity of staff and volunteers to meet it. The opportunity to work for humanitarian causes drew women who wanted to do something to support the U.S. cause during World War II. In addition to the options described above, women pursued other outlets through the Red Cross that relieved stress for individuals and families in crisis.

Debra A. Reid, Curator, Agriculture and the Environment, with Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life, The Henry Ford

The roof of The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation covers nearly 12 acres. A one-inch rainfall results in almost 326,000 gallons of water landing on that expansive roof.

Where does the runoff go?

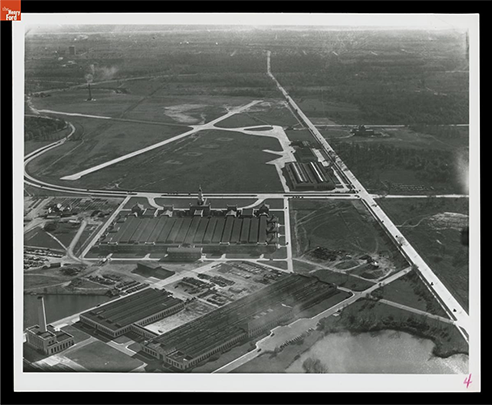

The architect, Robert O. Derrick, and landscape designer, Jens Jensen, who planned the building and grounds, cloaked the infrastructure that managed that runoff deftly. The following article walks you through the route that the water takes as downspouts and pipes move it from the museum roof to a 2.5-acre pond behind the museum and on to the nearby River Rouge. Today the pond, out of sight to the public, plays a vital role in reducing the risk of flooding and silt buildup in the nearby River Rouge, and it enables the reuse of runoff to irrigate the grounds.

Pond located north of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and southeast of the Dearborn Transit Center (upper right). / Drone photograph courtesy of Bart Fraley.

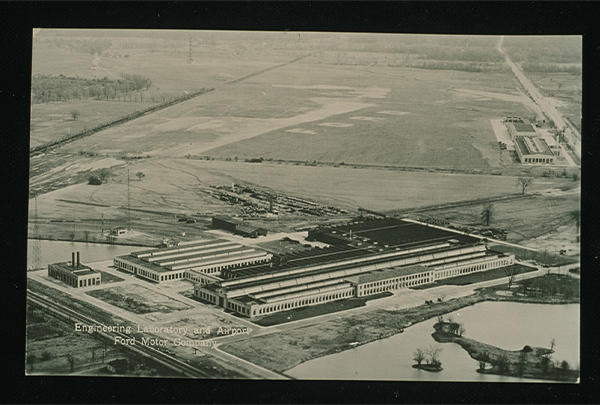

The pond predated the 1929 founding of The Edison Institute.. It and another set of ponds to the west resulted from clay extraction by a local brickyard. The Ford Motor Company built a powerhouse next to the eastern most pond at the Ford Engineering Laboratory. This pond became the holding tank for runoff from the museum roof.

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Landscape architect Jens Jensen mapped “the pond” behind “the museum building” in December 1931. Moving water from the roof to the pond begins with downspouts embedded into museum walls and structural columns throughout the Great Hall. Because this flow enters the system above ground, gravity moves it into the drainage infrastructure under the museum.

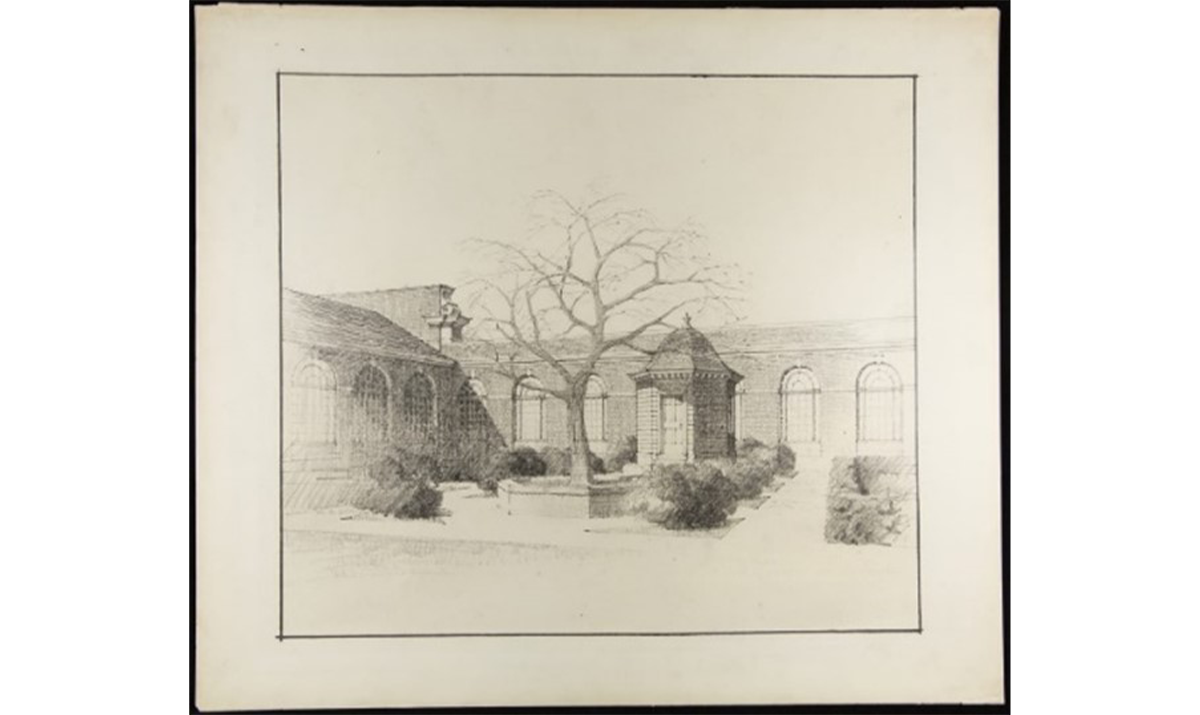

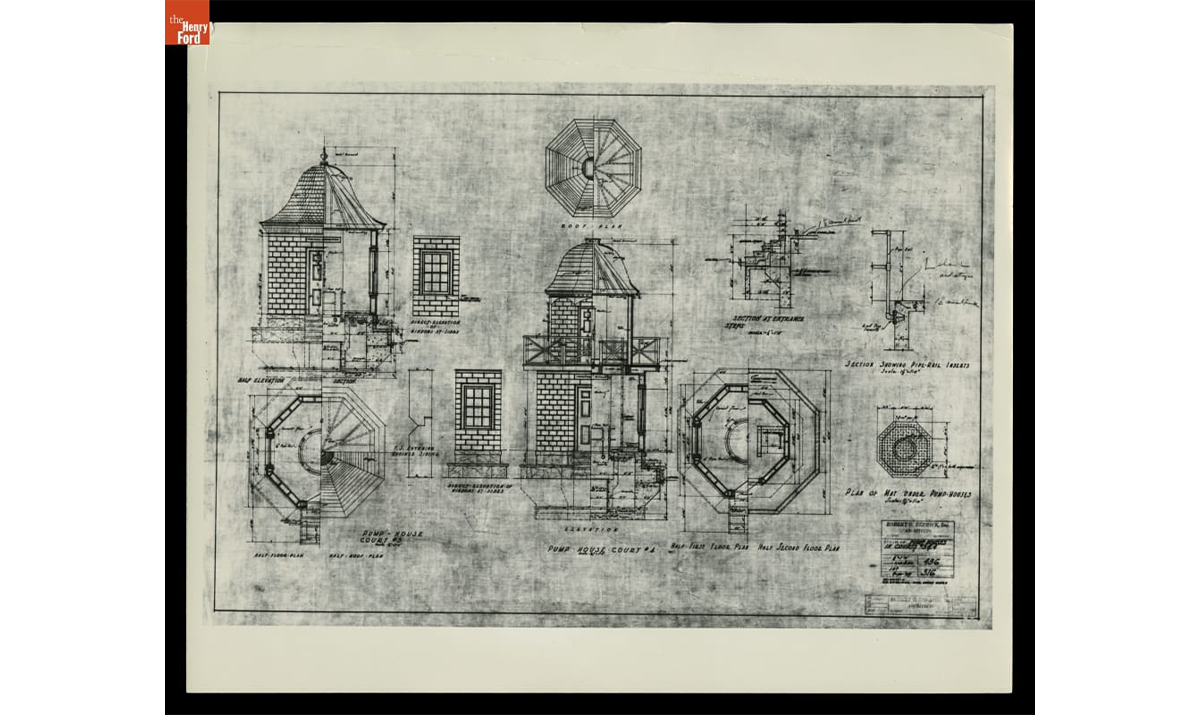

Rainwater also flows into yard drains around the museum. Since the yard drains are below grade, the system needed pumping stations to collect and pump water vertically to send water up and into the roof-water collection system closer to ground level. Architect Robert O. Derrick incorporated two pumphouses into his museum plans in 1928 to house these pumping stations.

Derrick, noted for his Colonial-revival designs, disguised the pumping stations in reproductions of other structures popular during the Colonial-revival era. The inspiration included a garden feature from Mount Vernon, home of George and Martha Washington, and the observatory that astronomer David Rittenhouse built in Philadelphia after he moved there in 1770. Rittenhouse gained international attention in 1769 because of his observation of the transit of Venus. His relocation to Philadelphia in 1770, the largest city in the Colonies at the time, facilitated his engagement with the vibrant scientific community there. Contemporaries described his Philadelphia observatory as “a small but pretty convenient octagonal building, of brick” [William Barton, Memoirs of the Life of David Rittenhouse (1813), note 111].

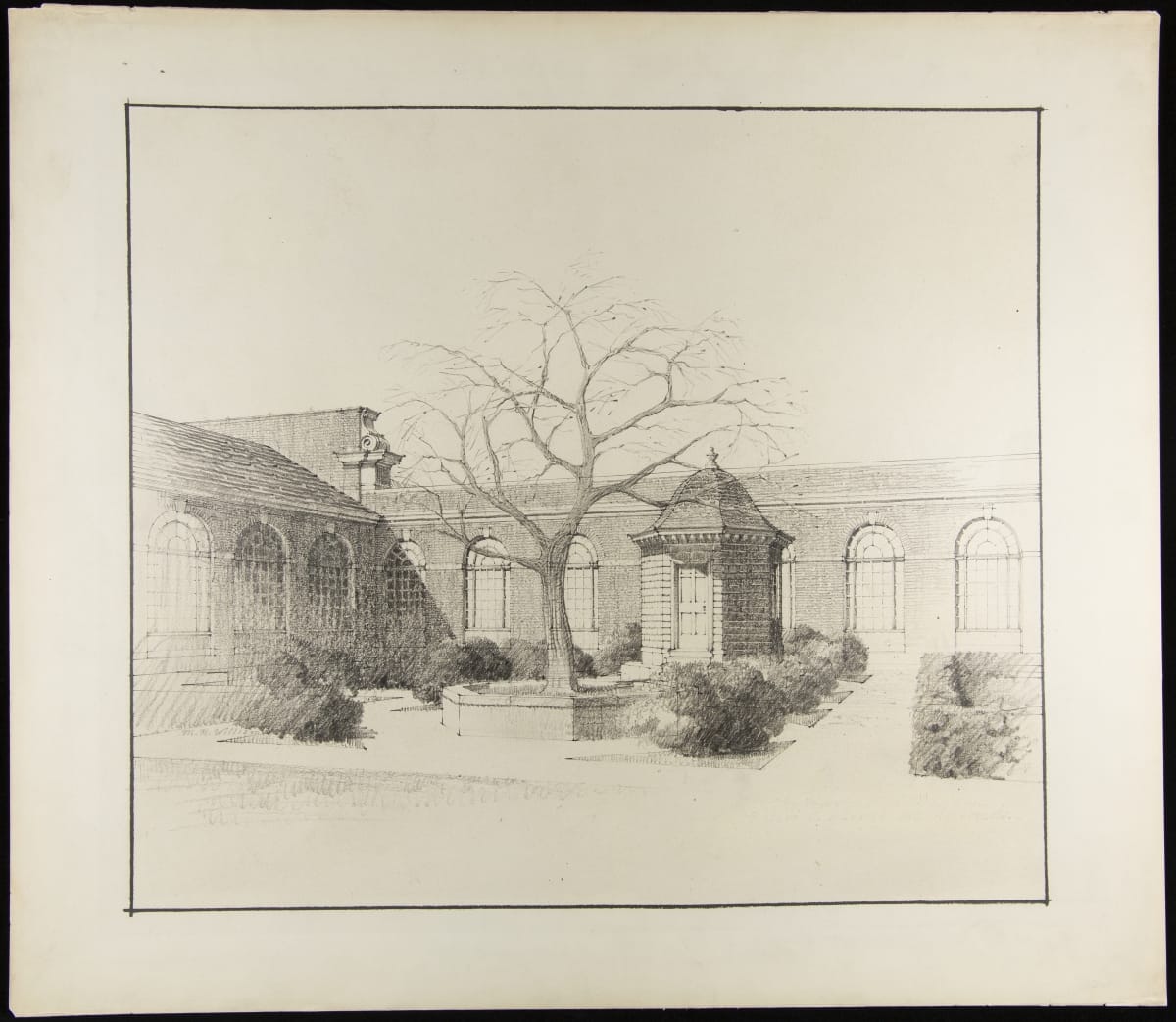

Virginia Court pumphouse based on a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

Pennsylvania Court pumphouse based on Rittenhouse’s observatory, 1928 / THF294392

The stations, located in each of the two large courtyards on each side of the main entrance to the museum, hold water and pump it into the stormwater infrastructure as needed.

Details of pumphouses in museum courtyards, drawn by Robert O. Derrick, Inc., Architects, 1929 / THF98551

Gravity facilitates rainwater flow to a 24-inch main line under the museum, which channels runoff to the basement of the powerhouse in the back of the museum. Facilities staff replaced the entire ductile iron system in the powerhouse basement during 2025 with stainless steel. This was the first replacement since the entire system was built in 1929.

Storm-pump system in the powerhouse basement. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

Two 75-horsepower motors, located in the basement of the power house, handle large storms. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

In what's designed as a "wet" system, water always fills the lower portion of the infrastructure. As rainwater drainage increases the pressure in the system, it pushes water out of the museum and into the retention pond.

What happens after rainwater runoff enters the pond?

The retention pond allows sediment to settle out of the water within the pond rather than in the River Rouge. It also accumulates for later use to water the grounds around the museum, Lovett Hall, and the Josephine Ford Plaza. A large irrigation pump draws water from the pond to the irrigation piping.

The stormwater management system within Greenfield Village converges near the Suwanee dock and flows into the Suwanee Lagoon. The water in the lagoon is regulated by a drain that flows into the Oxbow which connects to the River Rouge. Facilities staff can use a pumping station at the Oxbow to increase the rate of pumping into the River Rouge in case of excessive rainfall. That pumping station also works as a protection. If the River Rouge is too high, a valve can be exercised to prevent backward flow into The Henry Ford's stormwater management system.

Each pond in the Village serves as a large holding tank with an inlet on one side and outlet on the other, depending on which direction the water needs to flow to reach the Suwanee.

Mill pond construction in the Greenfield Village craft area, March 2003 / THF10348

Mill pond in Greenfield Village’s craft area. / Photograph courtesy of Lee Cagle, May 2018.

Water within the system irrigates lawns and gardens within the Village. A large irrigation pump near Henry Ford Academy draws water from the Suwanee Lagoon for this purpose.

Overall, the water management system has been integral to The Henry Ford’s efforts to reduce waste and reuse runoff. An overview of five years of Green Museum Work undertaken from 2019 through 2024 acknowledges this system as one of the historic precedents and an inspiration for current efforts. It takes staff expertise, financial commitment, and regular maintenance to continue such efforts, but the investment pays off in reduced water bills and healthier riverine ecosystems. Updates to the system during 2025 should prepare it for the next 100 years.

Jon Bennett is Assistant Construction Manager and Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. The title of this blog was inspired by Al Green’s and Mabon “Teenie” Hodges 1974 song by the same title.

Agriculture in Hawaii: Pineapple

Pineapple cultivation in Hawaii confirms global movement of plants and people. The sweet tropical fruit (Ananas comosus) originated in South America. Then, Portuguese and Spanish colonizers transported the crop from the Western to the Eastern Hemisphere. Reputedly, the Spanish horticultural experimenter Francisco de Paula Marín moved the pineapple on to Hawaii in 1813.

Pineapple field in Hawaii around 1910 / THF200642

The pineapple transitioned from a novelty to a market crop slowly. First, planters focused on sugar cane, not pineapples, but changes in land and labor resources benefited growers of both crops. Namely, planters negotiated with Hawaiians for permission to recruit men from Asia, especially from Japan and China, to work on contract with native Hawaiians to raise cane and refine it into sugar. Ronald Takaki documented the experiences of these laborers as they created a working-man's culture on sugar cane plantations in Pau Hana: Plantation Life and Labor in Hawaii, 1835-1920. Hawaiians also abandoned traditional land-management practices that allowed planters to consolidate land.

Japanese and Chinese laborers worked along with Hawaiians at menial and management tasks as pineapple production increased. They prepared fields, transplanted the crop, and tended it over two years as it matured. They also constructed canning plants, harvested the crop for canning, and prepared shipping crates.

Some Japanese families farmed their own small pineapple fields. They performed field trials when John Kidwell, an Englishman who had relocated to California, began testing different types of pineapple. One, the Smooth Cayenne variety from Florida, appealed to planters for size and taste, and it became the standard crop grown in Hawaii.

Can label, "Gold Band Brand Sliced Hawaiian Pineapple," 1898-1930 / THF113853

Asian laborers remained at work in island fields after the United States annexed Hawaii in 1898 and incorporated the islands as a U.S. territory in 1900. Yet, U.S. immigration restrictions reduced the movement of Asian contract laborers onto the islands. Efforts to increase the number of white laborers and homesteaders in Hawaii never met expectations. Instead, planters continued to rely on short-term labor contracts to recruit temporary workers from the Philippines, or planters recruited laborers from other countries, namely Portugal and the Caribbean islands. These individuals could have acquired knowledge of the crop through previous experiences.

A pineapple field, southern Florida, 1904 / THF624691

A pineapple field, southern Florida, 1904 / THF624691

Schoolchildren might learn about pineapple cultivation from stereographs like this one, which shows the hard work of harvest in three dimensions. The image shows Black laborers in southern Florida wearing gloves and forearm coverings to protect them from the spiky leaves. The reverse of the stereograph explains the process of raising pineapples.

Harvesting Indian River pineapples in Florida, 1900-1910 / THF624683

Florida ranked as the center of fresh pineapple production in the United States around 1900, and additional fields in California and the West Indies supplemented the Florida crop. The stereograph shows and describes the process of harvesting pineapples for the fresh market. Laborers cut the fruit and handled it carefully to prevent bruising. The packers in the shed in the background (next to the water tank) laid the tender fruit in wooden packing crates to protect them during the trip to East Coast markets.

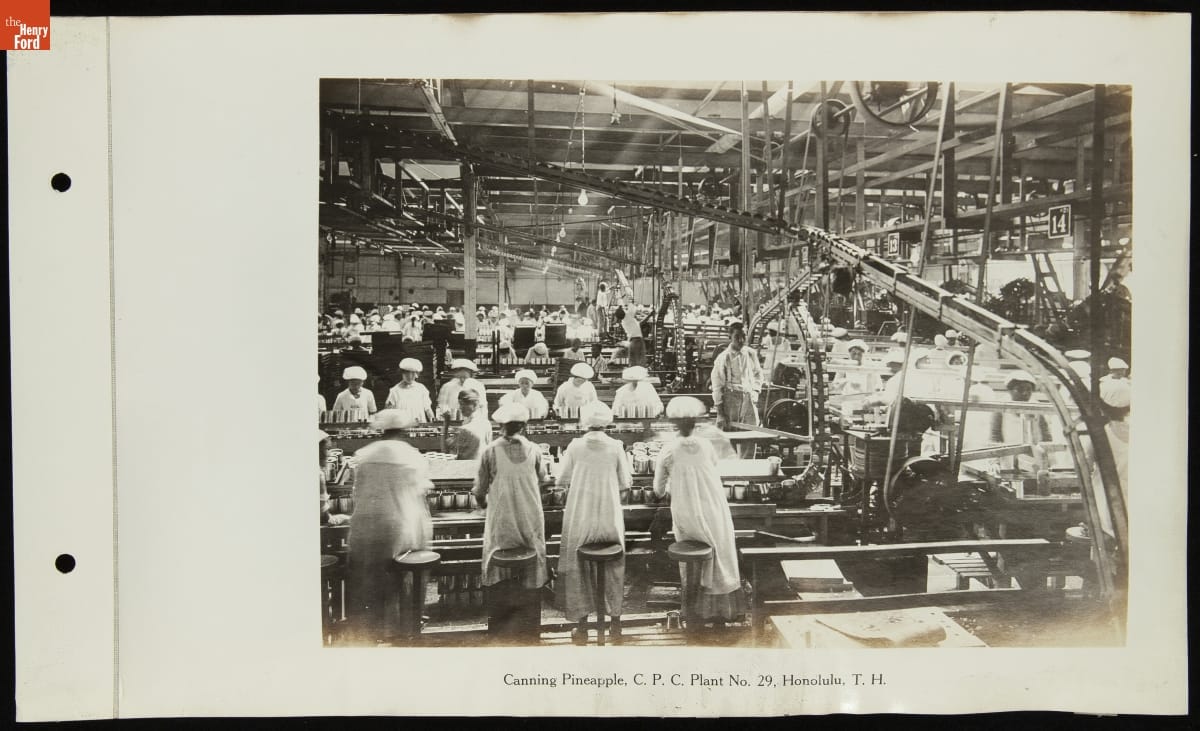

The canned pineapple business in Hawaii quickly outpaced the fresh fruit business closer to U.S. mainland markets. Years of engineering made the canning plants as mechanized as possible to reduce labor and ensure quality canned goods. A first step in the process required a machine that precisely cored the pineapple. James D. Dole, Hawaiian Pineapple Company, contracted with engineer Henry G. Ginaca in 1911. The Ginaca Pineapple Processing Machine resulted, patented, and further refined to increase the number of pineapples that could be peeled and cored in one minute. As John Wesley Coulter notes in his 1934 Economic Geography essay “Pineapple Industry in Hawaii,” it took less than five minutes to prepare one ton of fruit for canning.

Packing pineapple, California Packing Company, Plant no. 29, Honolulu, circa 1922 / THF276827

As machines whirred, women sat on stools selecting “fancy” sliced pineapple and packing it into cans while others sorted and packed the standard grade. Others picked up irregular pieces for the lowest quality (and priced) can. Each line in the cannery kept a set number of women busy, and a man monitored the mechanics as depicted above in the photograph of Plant no. 29 in Honolulu.

“Fancy Quality” Royal Arms sliced Hawaiian pineapple, 1930-1939 / THF715748

A report on women working as wage laborers in seven Hawaiian canneries indicated that between the 1890s and 1920s, the total canned pineapple increased from 2,000 to 9 million cases. Women accomplished this work in clean and well-maintained factories, which were uniformly sanitary and modern according to Caroline Manning in her 1930 article for the U.S. Department of Labor Bulletin, "The Employment of Women in the Pineapple Canneries of Hawaii."

Women packing sliced pineapple into cans at the California Packing Corporation Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276640

Manning also reported that relatively few women — just over 14,000 — worked at wage-earning jobs in Hawaii, and most worked as agricultural laborers on sugar plantations. Of all wage-earning women in Hawaii, 65 percent were Japanese and 10 percent were Hawaiian or of Hawaiian descent. The remaining 25 percent were predominately women from Europe or the Americas working in clerical positions, with a few hundred women from China, the Philippines, and Korea employed in various wage-earning occupations. In canneries, women of Asian origin constituted 87 percent of the work force: Japanese (32 percent), Hawaiian (27 percent), Chinese (19 percent), Filipino (5 percent) and Korean (4 percent).

Women monitoring crushed pineapple. California Packing Corporation Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276667

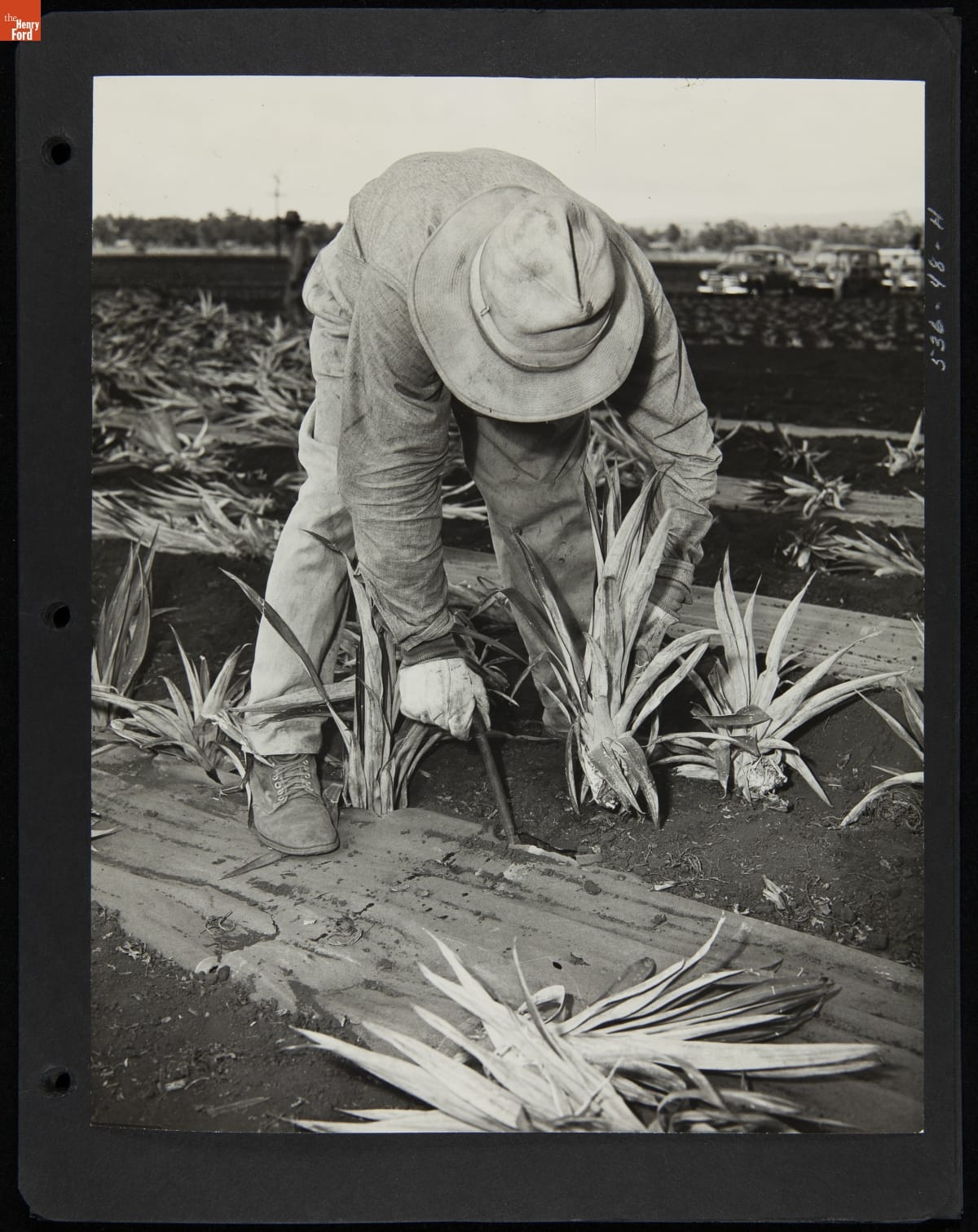

Labor Bureau researchers confirmed about a dozen Japanese women working in the fields, usually alongside men in their families. The women removed crowns from the pineapples and packed them in crates for shipment to canneries. They also trimmed crowns, slips, and suckers in preparation for planting the next year's crop.

Laborers on these plantations sometimes secured lodging, water, electricity and fuel, medical treatment, garden space, and provisions available for purchase at a company store. Around 1950, the California Packing Corporation documented changes in Hawaii Pineapple Operations. One photograph shows children playing near worker housing covered with corrugated tin roofs.

Labor housing, California Packing Corporation, Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276665

Other photographs in the California Packing Corporation album, taken around 1950, show the physically taxing work of pineapple planting, cultivation, and harvest. The canning companies tried to reduce labor needs by mechanizing planting and harvest, and developing a paper mesh to reduce the need for cultivation as the crop matured over two years.

Using a dibble to plant pineapple crowns. California Packing Corporation Hawaii Pineapple Operations, circa 1950 / THF276612

A taxi-type planter carried men who planted crowns, slips, or suckers as they moved through the field, circa 1950 / THF276673

Laborers harvesting pineapples that move along the conveyor belt to a holding container on the harvester, around 1950 / THF276606

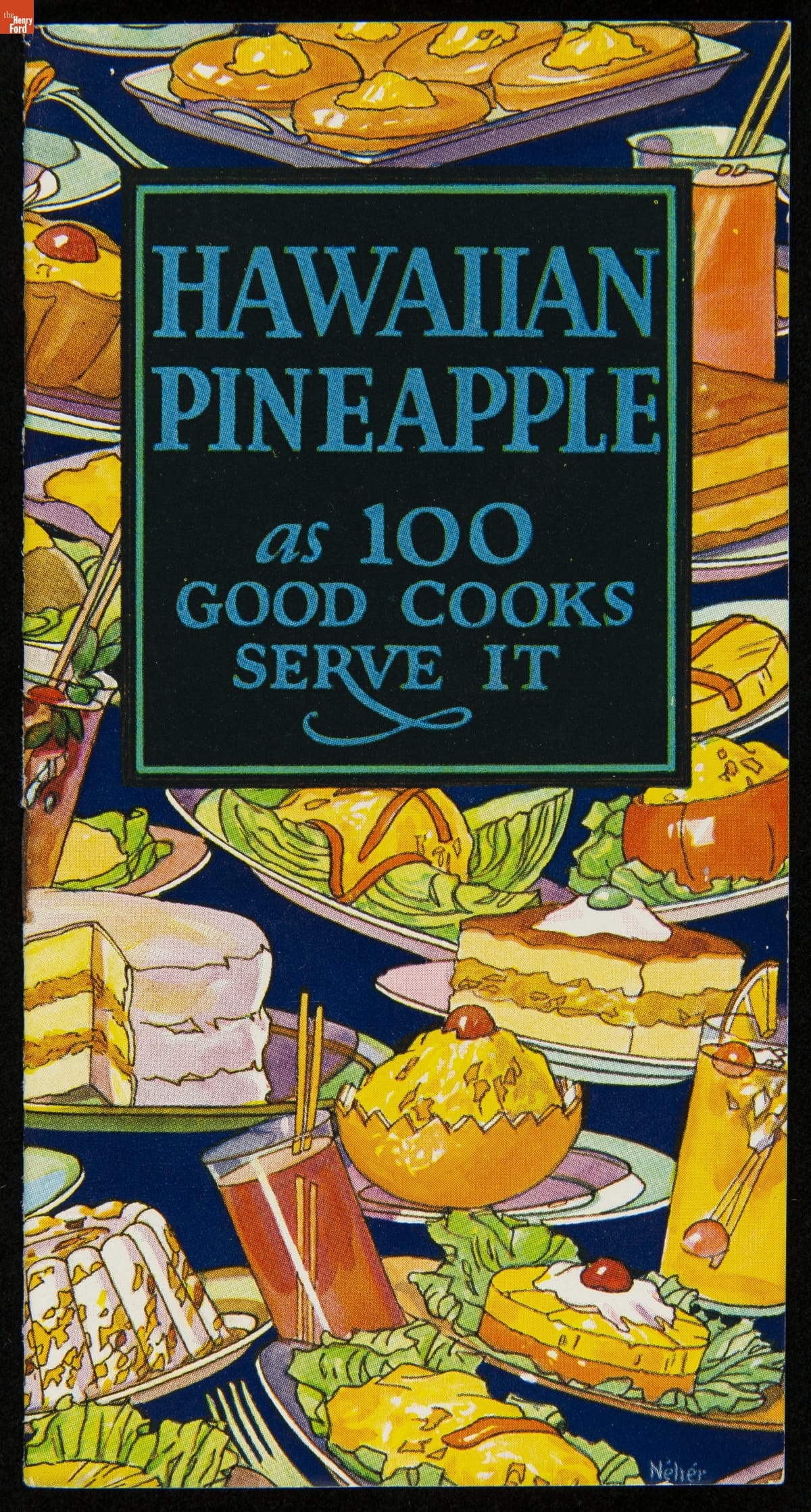

Recipe Booklet, "Hawaiian Pineapple as 100 Good Cooks Serve It," 1928 / THF294797

Then next time you pick up a can of Hawaiian pineapple, consider the global movement of plants — and the histories of the people who contributed to it. Be mindful of the laborers who worked in pineapple fields and canneries during the twentieth century. Increasing your knowledge about who works in pineapple canning plants today can make you a more informed consumer. You also might explore the pineapple by trying out a recipe published in one of The Henry Ford's historic cookbooks, Hawaiian Pineapple as 100 Good Cooks Serve It (1928).

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Acquiring an Agras MG-1 Drone

"Agras MG-1" Drone, with remote control, battery, and battery charger, 2016. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF199347

Curators at The Henry Ford document milestones in their given areas of responsibility. For agriculture and environment collections, one significant recent development involves uses of uncrewed aerial technology — popularly known as drones — to apply growth enhancers (fertilizers) and plant protectors (herbicides and pesticides) to specific locations in fields, vineyards, and orchards. Curator Debra Reid began conversations with the Michigan Soybean Committee in 2023 to secure a drone for our collections to document this aspect of precision agriculture.

Drones flew on military missions, predominately, until the early 2000s. One example includes the 1918 Kettering Bug, described as the world's first "self-flying aerial torpedo.” As a Smithsonian Magazine article explained, “the simple, cheaply made 12-foot-long wooden biplane with a wingspan of nearly 15 feet” included “a 180-pound bomb. It was powered by a four-cylinder, 40-horsepower engine manufactured by Ford.” These precision-based technologies aimed to put fewer pilots at risk.

Employees of the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company Working on the Kettering Bug, 1918 / THF270430

Other drones in The Henry Ford’s collections address robotics in aerial photography and stunts.

3DRobotics Solo Drone, 2015-2016. Gift of Industrial Designers Society of America / THF193809

3D Robotics (3DR) released its Solo drone in 2015 to great fanfare. NBC News claimed the Solo, when paired with a GoPro HERO camera, could take Hollywood-quality shots. 3DR, the largest North American manufacturer of drones for consumers at the time, believed that the quadcopter with its open-source operating software would dominate the aerial photography market. It may have done so, but competition from the China-based Dajiang Innovation Technology Company (DJI) challenged 3DR and outmaneuvered the Berkeley, California, company. In response, 3DR abandoned the drone manufacturing business and DJI came to dominate the hobby market for uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs).

Front view of the "Agras MG-1" Drone with propellers folded to show the radar module, spray tank, spray nozzles, and landing gear, 2016. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF199333

DJI manufactured the Agras MG-1 specifically for the growing market in precision agriculture and advertised the octocopter as “designed for variable rate application of liquid pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides, bringing new levels of efficiency and manageability to agriculture." Farmers found the investment paid off in numerous ways. They reduced input costs by reducing the quantity of synthetic chemicals applied. Additional environmental benefits included reduced run-off that negatively affects water quality and reduced greenhouse gas emissions because farmers used less fossil fuel during application. Reducing vehicular traffic also improved field health by reducing soil compaction which supported regenerative agriculture goals.

The rapid expansion of hobby and commercial drone markets prompted licensing regulation. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) required commercial drone operator licensing in 2016, but some schools had anticipated the need. Northwestern Michigan College first offered a course in Uncrewed Aerial Systems operation at the Yuba Airport in Grand Traverse County, Michigan, in 2010, becoming one of the first schools in the United States to do so. In 2013, NMC launched an Associate in Applied Science degree with a specialization in UAS. Then, NMC purchased one of the first DJI spray drones used in the United States, according to Tony Sauerbrey, UAS program manager at NMC. The Agras MG-1 facilitated the rapid expansion of commercial drone use in Michigan farm fields.

Instruction in Agras MG-1 operation. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF717085

Learning to operate the Agras MG-1, dispensing water, rather than chemicals. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF717084

The Agras MG-1 in flight over a Michigan vineyard. Gift of Northwestern Michigan College / THF717081

DJI designed the Agras MG-1 to carry 22 pounds of liquid pesticides, herbicides, or fertilizers — an amount that could treat an average of an acre in 10 minutes. Its “intelligent” operating system relied on global positioning systems (GPS) data to fly level to the terrain and to automatically adjust the quantity of spray to the flying speed and thus ensure even distribution. Operators had to understand the inputs as well as ways to override them if the battery ran low, the tank ran dry or changes in the weather made it difficult to operate the drone safely.

Rapid expansion in drone-aided agriculture led to training alliances. NMC partnered in 2017 with Michigan State University's Institute of Agricultural Technology so MSU students could meet drone licensing requirements. NMC also partnered in 2020 with Unmanned Systems Institute which administered additional industry safety certifications. Instructors need up-to-date technology, not dated UAS. Thus, NMC retired its Argas M-1, and we acquired it to document early UAS use in precision agriculture.

Debra Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Green Museum Work at The Henry Ford

The Henry Ford identified “Cultivating Environmental Responsibility” as one of its strategic goals in anticipation of its 100th anniversary in 2029. A few staff began assessing factors relevant to this goal in August 2019. The Henry Ford’s Green Team (previously the Environmental Focus Group) emerged out of this work and formally organized in May 2021 with responsibilities to benchmark and manage THF’s energy and water use and to reduce waste by recycling and composting. This work aligns with a call to action put forth in Sarah S. Brophy and Elizabeth Wylie’s The Green Museum: A Primer on Environmental Practice, namely, that going green “is becoming mainstream because of its importance, not its fashion” (pg 2).

You could argue that The Henry Ford has pursued green museum work since its beginning in 1929. Certainly, historical precedence lays a solid foundation for current initiatives. Three examples indicate how preservation, reuse, and local sourcing factored prominently in The Henry Ford’s history.

First, historic preservation is a green action. Committing to preservation and adaptive reuse rather than demolition reduces financial costs and energy expenditures.

Rebuilding the Clinton Inn in Greenfield Village, April 1929 / THF149382

Second, reusing landscape features supports actions that reduce environmental degradation. Namely a pond created by laborers excavating clay for use in Anthony Wagner’s brickyard starting in the 1860s became a rainwater holding tank for the museum. Design masked the multi-part infrastructure that re-purposed runoff from museum roofs for use in landscape irrigation.

Pond adjacent to Henry Ford & Son’s tractor plant, October 22, 1918, and north of The Henry Ford’s staff parking area today, remains central to The Henry Ford’s rainwater management system / THF116967

Museum plans drafted in 1928 incorporated pumphouses in two courtyards that pushed rain runoff through a drainage system and into the pond. Facilities managers take this history of environmental change into account when undertaking pond and pumping infrastructure maintenance.

Drawing of the Virginia Court with pumphouse replicating a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

Third, Henry Ford confirmed the importance of locally sourced materials when he constructed the chemical laboratory at the entrance to Greenfield Village. More than a dozen chemists worked in this structure, seeking domestic products for industrial use. By December 1931, soybeans became the focus of their research, and a new agricultural commodity took hold in southwestern Michigan. Ford joined others in Illinois, North Carolina, and beyond, exploring the potential of soybeans to meet local industrial demand for alternative oils for paint and alternative proteins for foods. Today we know that locally sourced products reduce carbon emissions by reducing transportation from the point of production to processing and consumption locations.

Chemical laboratory in Greenfield Village with Lovett Hall, The Edison Institute, visible in the background, 1930. This image predates Henry Ford instructing the chemists to focus on soybeans / THF236433

These historic approaches (among others) laid a firm foundation for Green Team actions over the past five years (2019 to 2024). Staff prioritized benchmarking, recycling, and composting as important steps toward cultivating environmental responsibility. Efforts aligned with national initiatives such as the Culture Over Carbon project, funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. More than 130 cultural institutions across the United States, including The Henry Ford, shared energy-use data that identified trends for the field. This supported a larger goal, to establish a cultural institution benchmark for Energy Star ratings.

Green Team members also engaged with Detroit’s 2030 District chapter through which they met with other museum and culture partners within and beyond the area. The national network of 2030 Districts, made up of businesses, cultural institutions, and municipal governments, all in efforts to pursue new models for urban sustainability and economic vitality. Ongoing conversations help put institutional work into context, including a signature accomplishment at The Henry Ford in 2024, namely, the installation and operation of the second biodigester in the Detroit area.

The Henry Ford staff, Amber Stankoff, producer (left) with Brian Egen, executive producer and head of studio productions (center), filming Alec Jerome, senior director of facilities management and security, discussing the biodigester installed at Stand 44, the new restaurant in Greenfield Village, June 26, 2024. Photograph by Debra A. Reid.

These actions are steps on the longer path toward cultivating environmental responsibility. Extending information more broadly to THF staff and guests makes clear how each of us will contribute to realizing this ambitious goal. Doing so will ensure a more stable environment for staff and guests in perpetuity.

Debra A. Reid is curator of agriculture and the environment at The Henry Ford and has been a member of the Green Team since its formation. She serves on the Climate & Sustainability Community of the American Association for State and Local History and is the secretary of the International Council of Museums' international committee, SUSTAIN (Museums and Sustainable Development).

Snowshoes: 2024 IMLS Feature

As we come to the end of our 2022-2024 IMLS (Institute of Museum and Library Services) grant project, the Conservation staff are showcasing standout objects recently treated. During the two-year project we have conserved and relocated 2,106 objects, and created fully digital catalog records for 815 of these. The following blog highlights the snowshoes that made their way through this grant, now made accessible to the public via The Henry Ford’s Digital Collections.

Snowshoes have a long history in North America. Indigenous peoples invented the form using thin strips of collagenous material (sinew or treated hide) and bent wood. The woven strips created a netting used for walking on snow. In fact, using snowshoes helped Indigenous peoples in snowy areas thrive during wintertime. The shoes facilitated trade, hunting, trapping, and self-defense. You can read more about the advantages of Indigenous snowshoe knowledge in Thomas M. Wickman’s book, Snowshoe Country: An Environmental and Cultural History of Winter in the Early American Northeast (2018).

Wickman focuses on the Wabanaki, including Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot peoples, in northern New England. The Wabanaki held advantage in the area during the 1600s, but by the early 1700s, British colonizers co-opted Indigenous tactics, including snowshoes, and launched winter offensives with the goal of eliminating their Indigenous opponents. Snowshoes then became a tool that British colonizers used for daily winter transport.

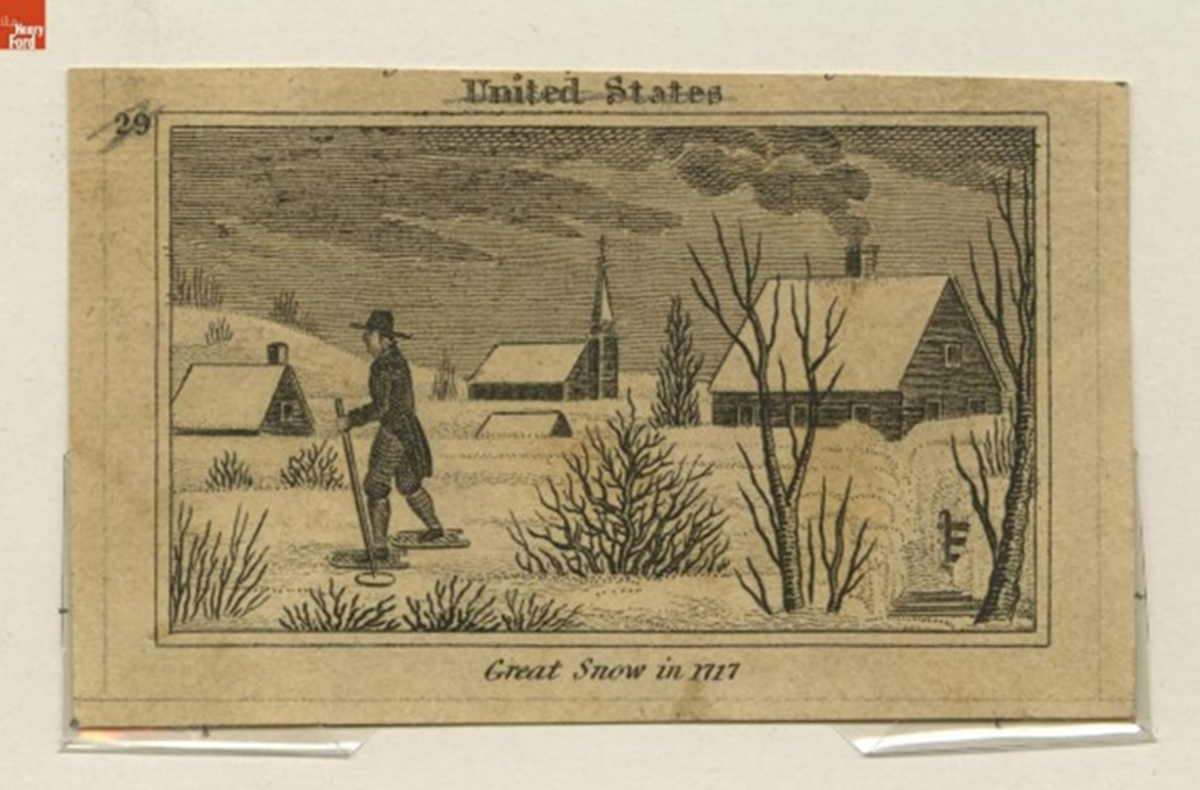

Copperplate engraving made around 1820, "Great Snow in 1717" / THF118620

A description of the “Great Snow Storm” of 1717, included in Historical Scenes in the United States (1827), described the snow as being so deep that “people stepped out of their chamber-windows on snow shoes.” The author, John W. Barber, mentions consequences of the 1717 snow, a “terrible tempest” that trapped New Englanders in upward of 15 feet of snow accumulated over several storms in late February and early March. The rather bucolic illustration does not convey the tragedy of the weather event. The 1891 book Historic Storms of New England does a better job. Author Sidney Perley puts the storm into context in his chapter, “The Winter of 1716-1717,” including the loss of livestock and humans. He also provides detail about those colonists who donned snowshoes, including mail carriers and residents who relied on the shoes to tend to livestock or assist neighbors, and sometimes to visit sweethearts.

Native American Basket Market, Ojibwa Tribe, Mackinac Island, Michigan, September 1904 / THF118996

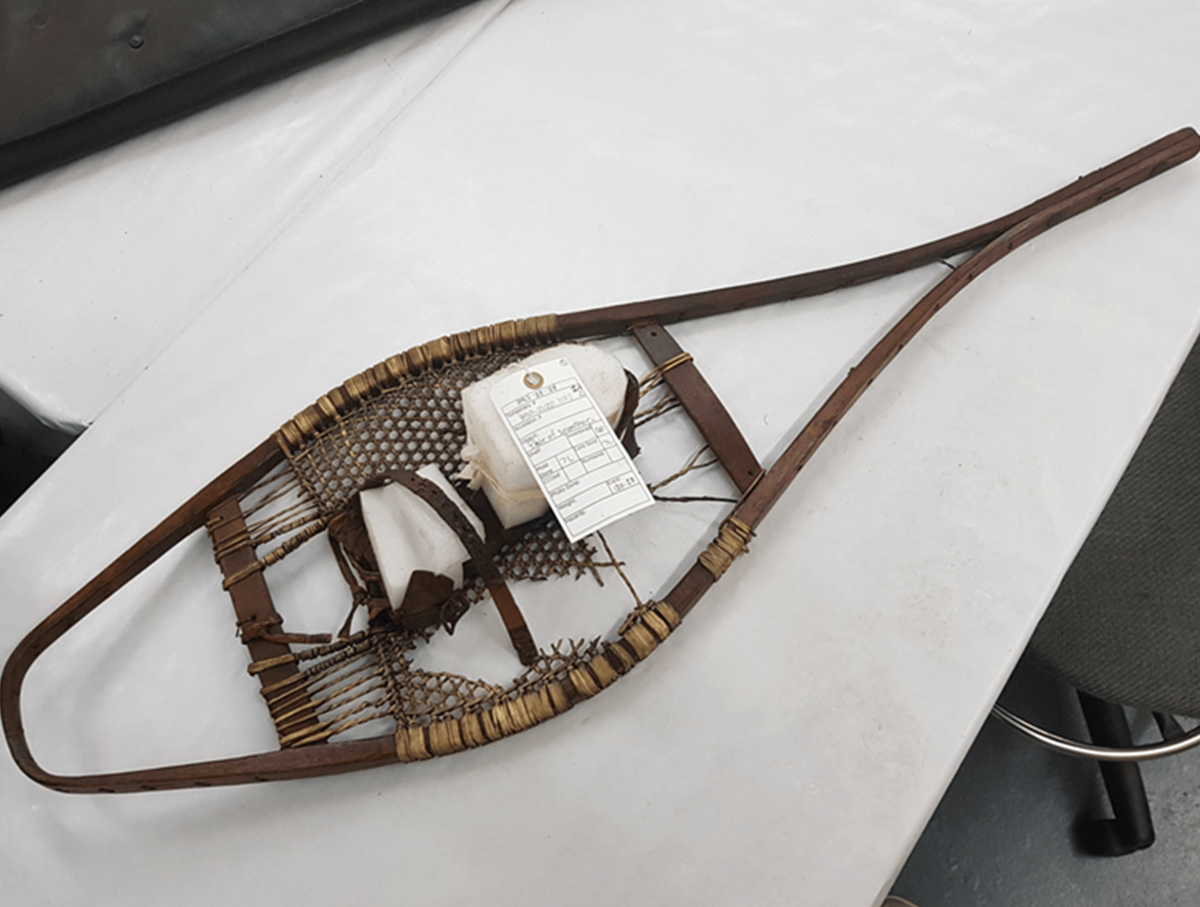

Indigenous knowledge remained essential to snowshoe construction. A photograph shows Ojibwa people selling baskets, and in the background, a pair of snowshoes leaning against a tree. The snowshoes treated during the IMLS grant project lack the decorative tufts of either dyed moose hair or wool visible on the Ojibwa snowshoes, but the intact webbing, carefully conserved, still indicates the craftsmanship evident in each shoe.

Some of the snowshoes in The Henry Ford’s collections still have their leather ankle loops and toe thongs intact. These details secured the toe to the shoe, leaving the heel free to lift the shoe and step forward with each stride.

The following images show the work of conservation, and the photography that was used to document our process. We are pleased to be able to share these remarkable artifacts via THF’s Digital Collections.

One shoe of a pair of snowshoes needed stabilization before proper handling. A section of the wood frame was missing, leaving sharp pieces of wood sticking out. The dowels keeping the tail together had split, causing more tension on the weakened rawhide webbing. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The tail was stabilized with painted wooden dowels inserted between the gaps that were secured with wood glue. The large loss to the wood frame was filled with a wood putty that was levelled, scored with a dental pick to create the wood grain, and painted to match the rest of the wood. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The rawhide was then cleaned with a mild detergent and distilled water with a stiff brush to remove as much dirt as possible. The rawhide webbing is rather sturdy, even where it had detached from the wooden frame, and was not in need of reattachment at this time. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

Another pair of snowshoes in a different shape from the previous pair has leather shoe holders attached to the mesh component made of rawhide. One-fourth of the mesh is missing, while the rest of the mesh was stained by dirt and dust. The overall surface of the leather was fragile, cracked, missing, and broken in some areas. A leather strap to hold the toes was split and separated from the object. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The leather was consolidated with Jade R adhesive and Japanese tissue attached to the reverse side of broken leather areas after cleaning with distilled water. The split leather strap was also reattached in the original position by the same restoration method. The restored areas by Japanese tissue were painted to match the rest of the leather. The rawhide was cleaned with the same method as described with the previous snowshoes. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

The leather shoe holder is held in place with a foam support to keep the shape and avoid further physical damage. Oil-based gel stain mixed with nutmeg and antique walnut color was applied on the wood surface of the object to match the rest of the color of the wood. / Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim)

Thanks to the work of the IMLS team, the care and conservation of these organic artifacts is complete. In the photo studio, the snowshoes presented even more complexities.

They proved to be one of the trickiest (and most delicate) objects photographed throughout the IMLS grant project. Senior photographer and studio manager, Jillian Ferraiuolo, outlines below how the snowshoes needed to be handled carefully to be properly photographed.

Snowshoes set up for photography / Image by Jillian Ferraiuolo

Because they are so large, the snowshoes were photographed on the ground, with white boards placed underneath to protect them from the floor. A white background also makes it easier to clean the background during the editing phase and remove anything that’s not a part of the object.

Object 2022.0.22.646 / THF800530

Object 2022.0.22.645 / THF800534

Object 2022.0.22.644 / THF800535

Photographing the snowshoes was one of the final steps towards getting these important objects added to THF’s Digital Collections webpage. Thanks to IMLS funding, these and more artifacts that tell agricultural and environmental histories have become more accessible.

This blog was written by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim), IMLS project conservator; Jillian Ferraiuolo, senior photographer & sudio manager; and Debra A. Reid, curator, agriculture and the environment.

Marlene Gray, senior conservator; Julia Fahling, conservation specialist; Eleanor Glenn, former conservation specialist; Mary Fahey, chief conservator; and volunteers (Eric Bergmann, Maria Gramer, Frances McCans, and Larry McCans) assisted Jee throughout the two-year grant project.

My friend Jennifer introduced me to Marian Morash’s The Victory Garden Cookbook (Alfred A. Knopf, 1982) in 2022. She explained that the cookbook was her mother's go-to wedding present. When Jennifer and her daughter saw a feature article about Mrs. Morash and her husband in Better Homes & Gardens (2017) they wrote her. They thanked her for the inspiration the cookbook provided three generations of cooks in Jennifer's family, and the modest Beard-Award-winning chef, author and TV personality wrote back, amazed that the cookbook could still be found.

Marian’s inspiration came from none other than Julia Child who passed along partially cooked foods from a cooking show that Marian’s husband, Russell Morash, piloted in 1962. The following summarizes the connections that laid the groundwork for the influential Victory Garden Cookbook.

Dust jacket, The Victory Garden Cookbook (1982). / THF708642

Hardcover, The Victory Garden Cookbook (1982). / THF708645

Morash's Background and Inspiration

Morash’s husband, TV producer Russell Morash, first encountered Julia Child, co-author of Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1962), on the WGBH-TV show I’ve Been Reading, in an episode likely broadcast on February 19, 1962. Child captivated WGBH-TV staff and viewers with her cooking demonstration, and the station decided to produce three pilot episodes of The French Chef. These aired in 1962 on July 26 (the omelet), August 2 (coq au vin) and August 23 (the souffle). The new series, The French Chef, debuted February 11, 1963. Marian’s husband, Russell Morash, produced the new series. The half-prepared recipes that Russell salvaged from the show, along with Julia Child’s directions written to Marian so she could complete the cooking, nurtured the nascent chef. In 1975, Marian co-founded Straight Wharf Restaurant in Nantucket, Massachusetts, and ran it as executive chef. Continue ReadingElectric Mower with 74-Inch Cut Comes to The Henry Ford

The Henry Ford has a grounds crew that works year-round to keep the expansive lawns in tip-top condition. Green practices have driven much of the care from the beginning. The millponds in Liberty Craftworks and behind A Taste of History are all part of a natural water filtration system that allows residue to settle out of rainwater runoff before it enters the Rouge River. That’s just one part of water management at The Henry Ford, however, because that water is also reused to irrigate the lawns.

The irrigation system keeps the yards lush. Thus, mowing consumes many an hour in the grounds crew’s schedule. A grant from the Aptiv Foundation Inc. funded purchase of a new Evo electric zero-turn riding mower. The 74-inch width means the grounds crew can cut more grass in a day (and the battery will power up to 8 hours of work on a single charge).

Continue Readinglawn care, nature, Greenfield Village, by Debra A. Reid, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford