Posts Tagged by kayla chenault

Women in Service: From the Civil War to WWII

Throughout history, women have served their country during war and in peacetime, on the home front and at the front lines. Since the founding of this country, both military and civilian women contributed to their nation’s cause—whether through active service, or by using their talents and time to support our fighting forces from afar—in ways that were and are often overlooked. Through these objects from the collections of The Henry Ford, we can explore some of these important stories, shedding light on women and their service.

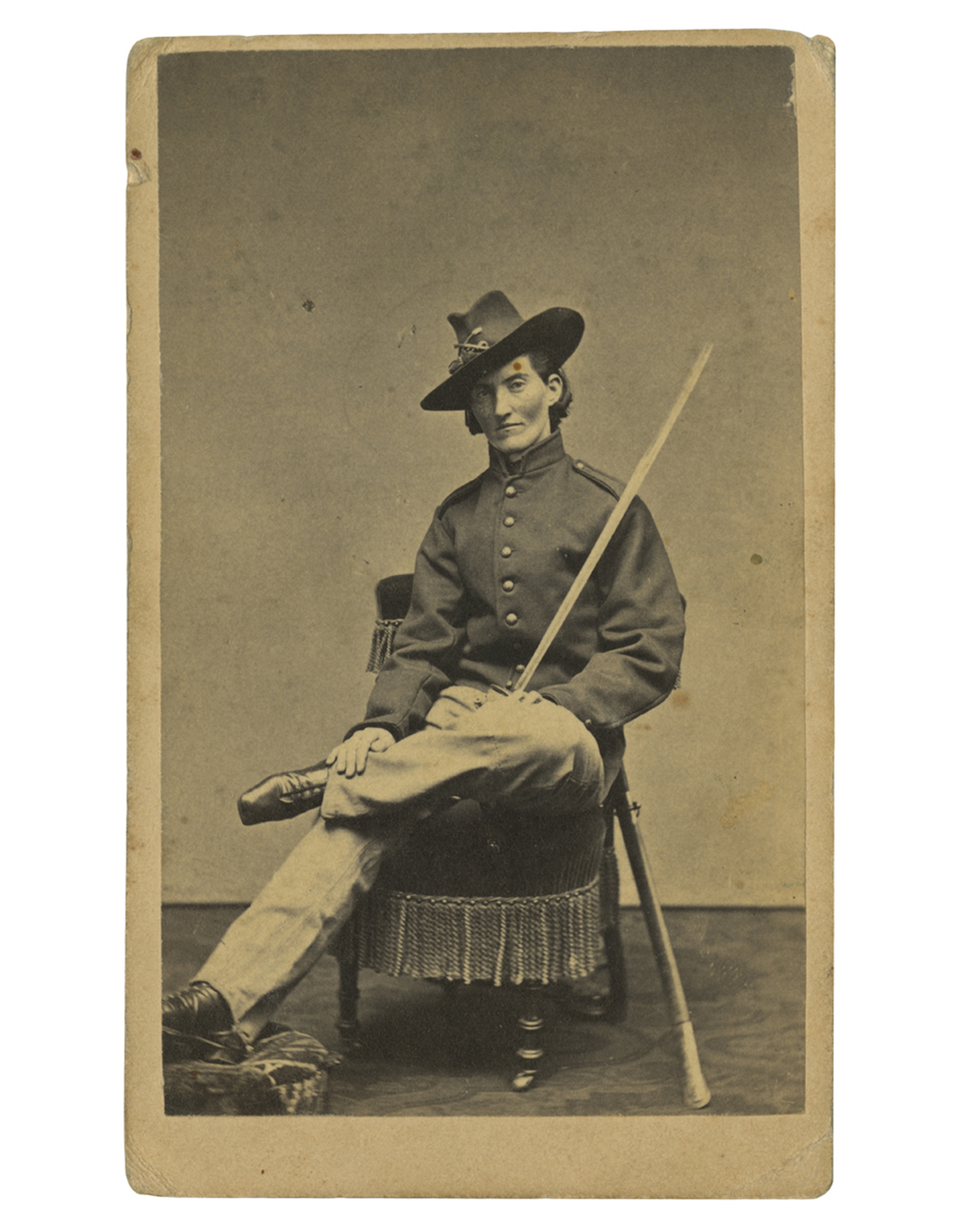

Frances Clayton

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

While women could not officially serve in combat roles in the United States until 2016, women participated in combat as early as the American Revolution—dressed as men.

During the Civil War, hundreds of women concealed their identities to enlist and fight in battles across the country. Their motivations varied: some wanted to stay close to husbands, brothers, or other loved ones, while others sought to defy societal norms, pursue adventure, or earn a soldier’s pay and enlistment bounty. Patriotism was another driving force—with northern women supporting the Union or abolitionist causes, and southern women joining to support the Confederacy.

At the time, joining the military was easier. With an urgent need for soldiers, physical exams were brief, and no identification was required. A woman could cut her hair, wear men’s baggy clothing, and adopt a male alias. Some were eventually discovered and sent home, others were wounded or killed during service, and others returned home, mustering out at the end of their service.

—Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator

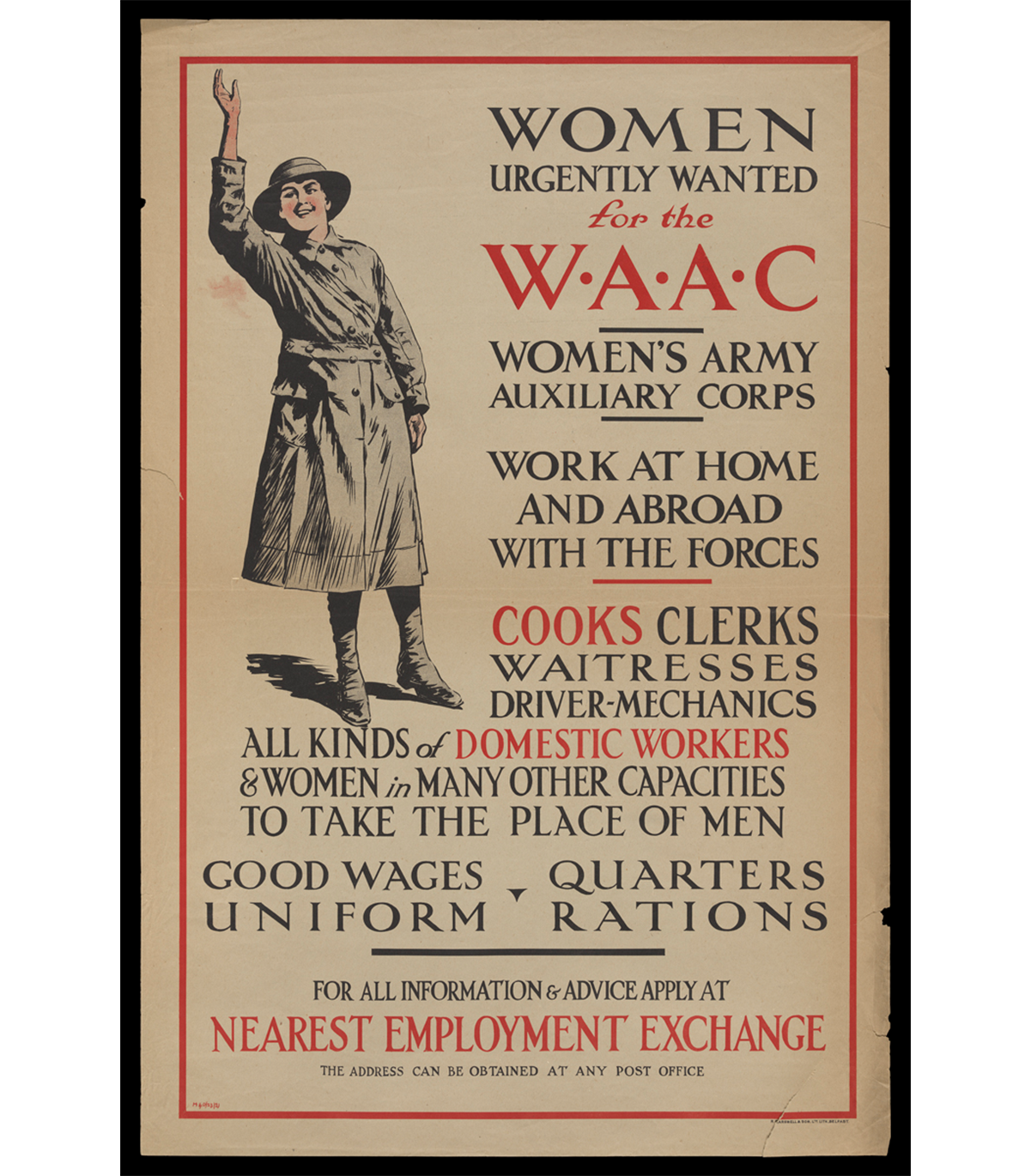

WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

Over 50,000 British women volunteered with the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1917 and 1918, the final two years of the First World War. WAAC volunteers took on support roles such as administrative work, catering, or vehicle maintenance at home in the United Kingdom and on the front in France and Belgium. In doing so, WAAC freed up British men on the front from non-combative tasks so the military could focus on the battlefield. This was the first time that women were allowed in the British armed forces in an official capacity outside of nursing.

The corps was renamed Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1918 after Mary of Teck, the queen consort of King George V, became the corps patron. The original WAAC/QMAAC disbanded in 1921, but it inspired women's auxiliary military corps in Great Britain and the Commonwealth and in the United States during the Second World War.

—Kayla Chenault, Associate Curator

“Molly Pitchers”

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

"Molly Pitcher" was the symbolic name given to several historic women who served during the Revolutionary War. These women, usually a soldiers' wife, were noted for carrying water and other provisions to frontline troops. But they became more famous for fighting alongside other soldiers after their husbands or loved ones had fallen in battle.

During the Second World War, August 4, 1943, was designated Molly Pitcher Tag Day. On that day, thousands of women throughout the United States dressed in early American or patriotic costumes and became contemporary "Molly Pitcher" heroines by selling war stamps and bonds. At Greenfield Village, Women's Army Corps recruiters from Detroit, Michigan, and four "Molly Pitchers" came together to raise money for the bond drive, shining a light on women's contributions—whether on the home front or in military service—to America's war efforts since our country's founding.

—Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator

Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

Husband-and-wife designers Charles and Ray Eames spent the early years of their partnership experimenting with molding plywood for use in furniture and sculptural objects. In the early 1940s, they used the spare bedroom in their Los Angeles, California, apartment to develop a machine to mold plywood using pressure. A friend, Dr. Wendell Scott of the Army Medical Corps, visited the Eames’ home and saw the potential of molded plywood for the war effort. America’s entry into World War II had created material shortages, including metal. Despite the shortage, metal splints were being used for broken limbs on the battlefield even though they were inflexible and heavy, and worsened wounds in transport.

Upon hearing this, the Eames designed a flexible, lightweight and durable leg splint using the same molded plywood technology they were developing for plywood furniture. They presented their prototype splint to the U.S. Navy and worked with them to further modify and perfect the product. By 1942, the Navy had placed an order for 5,000 splints. The Eames Leg Splint became a successful medical innovation and a design artifact, as well as a critical step in the Eames understanding of molded plywood.

—Adapted from What if Collaboration is Design? Katherine White, Curator of Design

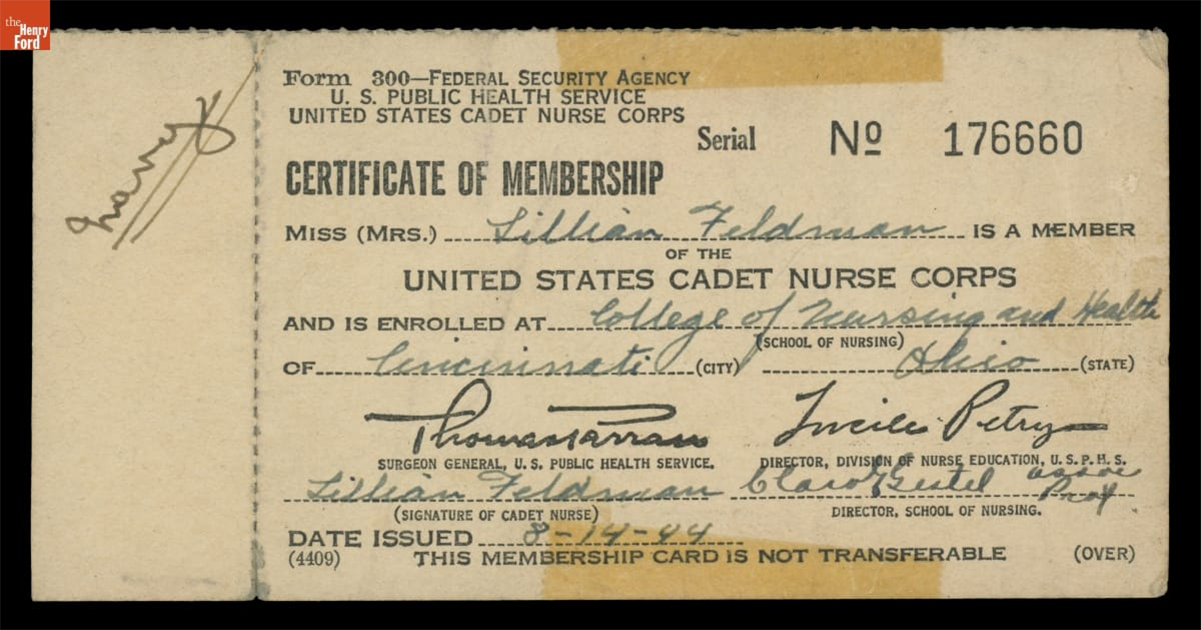

Lillian Schwartz, Nurse Cadet

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Feldman Schwartz (1927-2024) was an American artist who began working at the forefront of computer art and experimental film in the late 1960s at Bell Laboratories. Before her art career was established, however, her life was entwined and impacted by service in the medical field during the last years of WWII, and in its immediate aftermath.

In 1944, when Lillian was 17, she applied to the United States Cadet Nurse Corps—a tuition-free program designed to address the WWII nursing shortage. Lillian did well in her coursework, but she quickly realized that she struggled with nursing people. Despite this, she found ways to bring joy into the Cincinnati hospital where she worked by painting murals in the children’s ward and making plaster sculptures in the cast room. Lillian quickly realized that she was an artist, not a nurse. While working in the hospital pharmacy, she met an intern named Jack Schwartz, whom she would marry in 1946. In 1948, Jack was stationed in Fukuoka, Japan, and Lillian traveled to join him after the birth of her first son. Unfortunately, she developed polio symptoms several weeks after her arrival, and in the post-war aftermath, she was also exposed to the lingering effects of radiation from the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These experiences led to serious health issues throughout her life and were often referenced in her art projects and writing.

—Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

This collaborative blog was written by the staff of The Henry Ford

by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Aimee Burpee, by Rachel Yerke-Osgood, by Andy Stupperich, By Kayla Chenault, by Katherine White

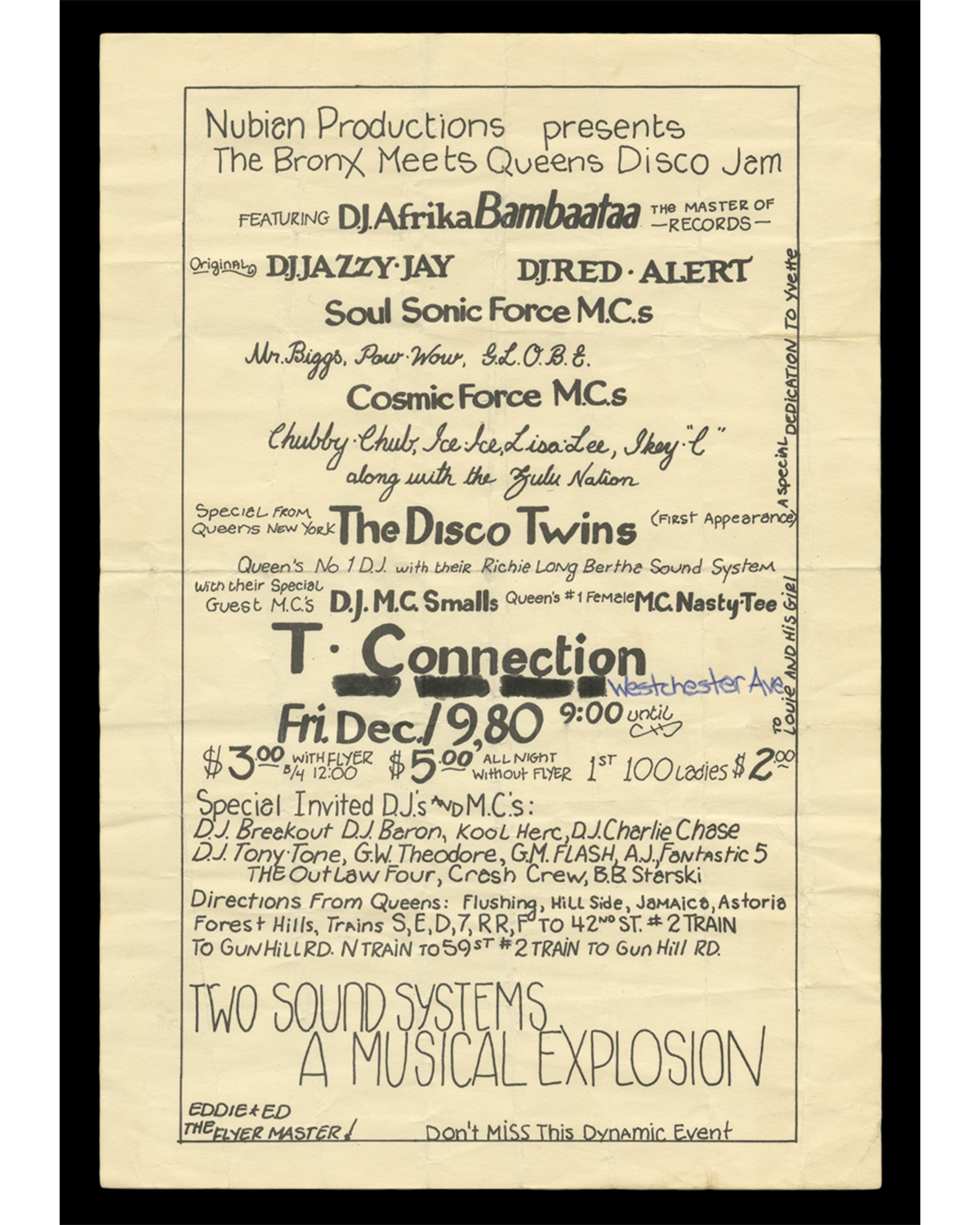

The Early History of Hip-Hop in Three Flyers

New York City was experiencing a time of turmoil from the late 1960s through the 1970s. The city, especially in the outer boroughs, was in depth of recession; urban renewal policies had harmed predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Youth gangs took to the street as the result of a lack of community resources, jobs, or third spaces for leisure. Out of this chaos, hip-hop rose from the Bronx. Young people created this culture at block parties, parks, and clubs. These gatherings were usually advertised with homemade street art-inspired flyers like the ones recently acquired by The Henry Ford. They offer a glimpse into the history of not just a musical genre but a movement.

"The Bronx Meets Queens Disco Jam Featuring DJ Afrika Bambaataa," 1980. / THF721980

"The Bronx Meets Queens Disco Jam Featuring DJ Afrika Bambaataa," 1980. / THF721980

In the early days of hip-hop, the disk jockey, or DJ, was the star of the show; their ability to create the atmosphere for a party is what made them, and hip-hop itself, unique. As hip-hop grew in popularity, DJs who were fixtures at neighborhood gatherings were invited to play in clubs for special nights. Among the most prominent of these clubs was a discotheque in the Williamsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx called T-Connection. DJ Flame, who performed as DJ La Spank in the 1980s, called the T-Connection the Apollo Theater of hip-hop in a 2023 interview. To her, T-Connection was a training ground for young DJs to hone their craft in front of audiences who expected greatness. T-Connection also featured hip-hop luminaries. DJ Kool Herc, who is considered one of the founders of hip-hop, often played there with his emcees, the Herculoids. DJ Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation were considered the unofficial in-house crew of T-Connection due to their frequent performances.

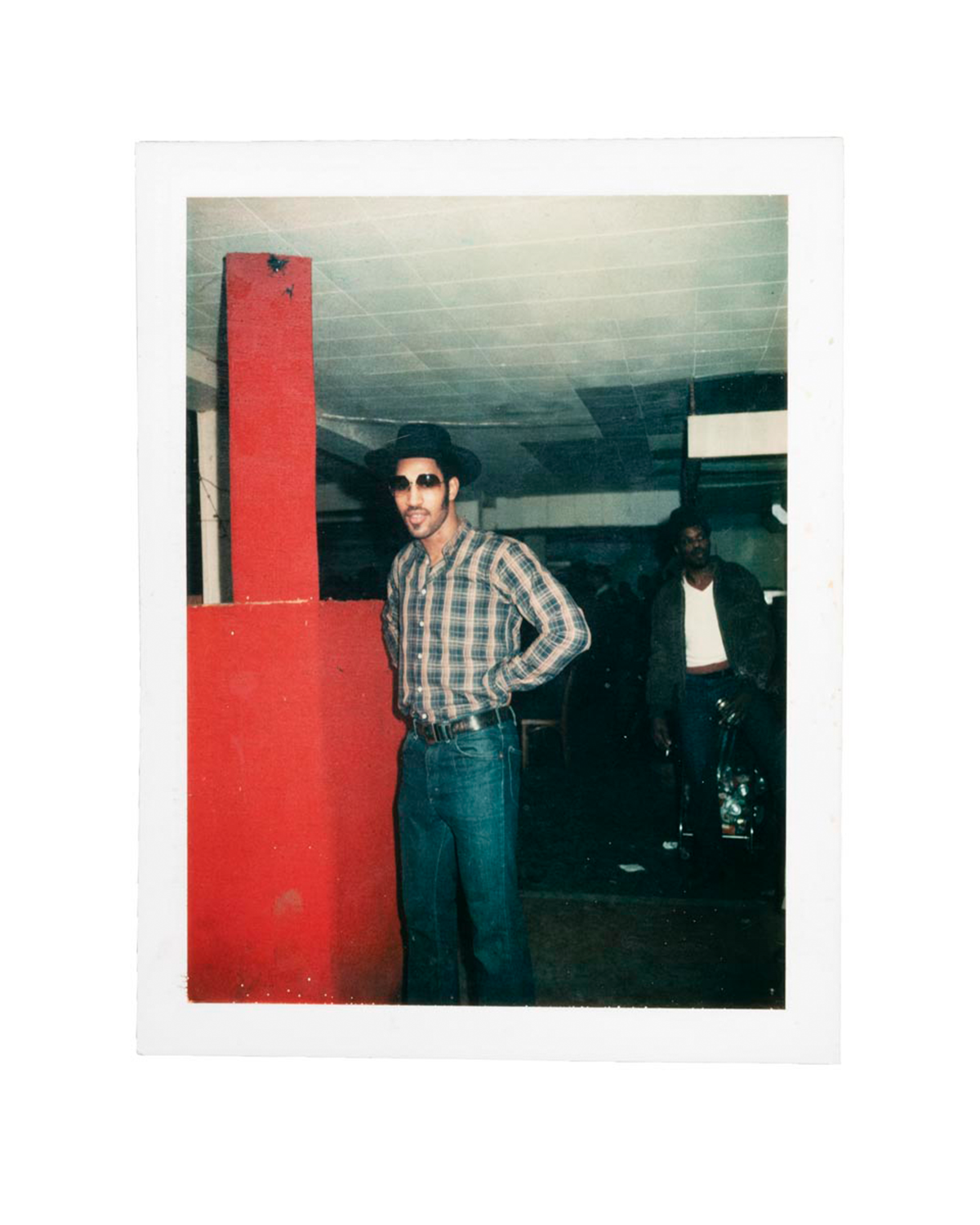

DJ Kool Herc at a nightclub, Bronx, New York, circa 1981. He is pictured in a nightclub, possibly T-Connection. / THF191960

DJ Kool Herc at a nightclub, Bronx, New York, circa 1981. He is pictured in a nightclub, possibly T-Connection. / THF191960

To be the center of a party, DJs cultivated large and mostly secretive libraries of vinyl records spanning soul, funk, disco, electronic, and rock music genres. Early hip-hop DJs focused on the breakdown or "breaks," the portions of a song where the percussion or rhythm sections of a band would do a solo. This was considered by many to be the most danceable part of a song. Some DJs, like Kool Herc or Grandmaster Flash, would extend the "breaks" in songs using two copies of the same records and playing them in succession, sometimes called the "merry-go-round" technique. You can hear the T-Connection audience’s response to DJs' hard work in surviving bootleg recordings of performances. At clubs like T-Connection, DJs demonstrated their prowess on the turntables and spread hip-hop across New York City and the world.

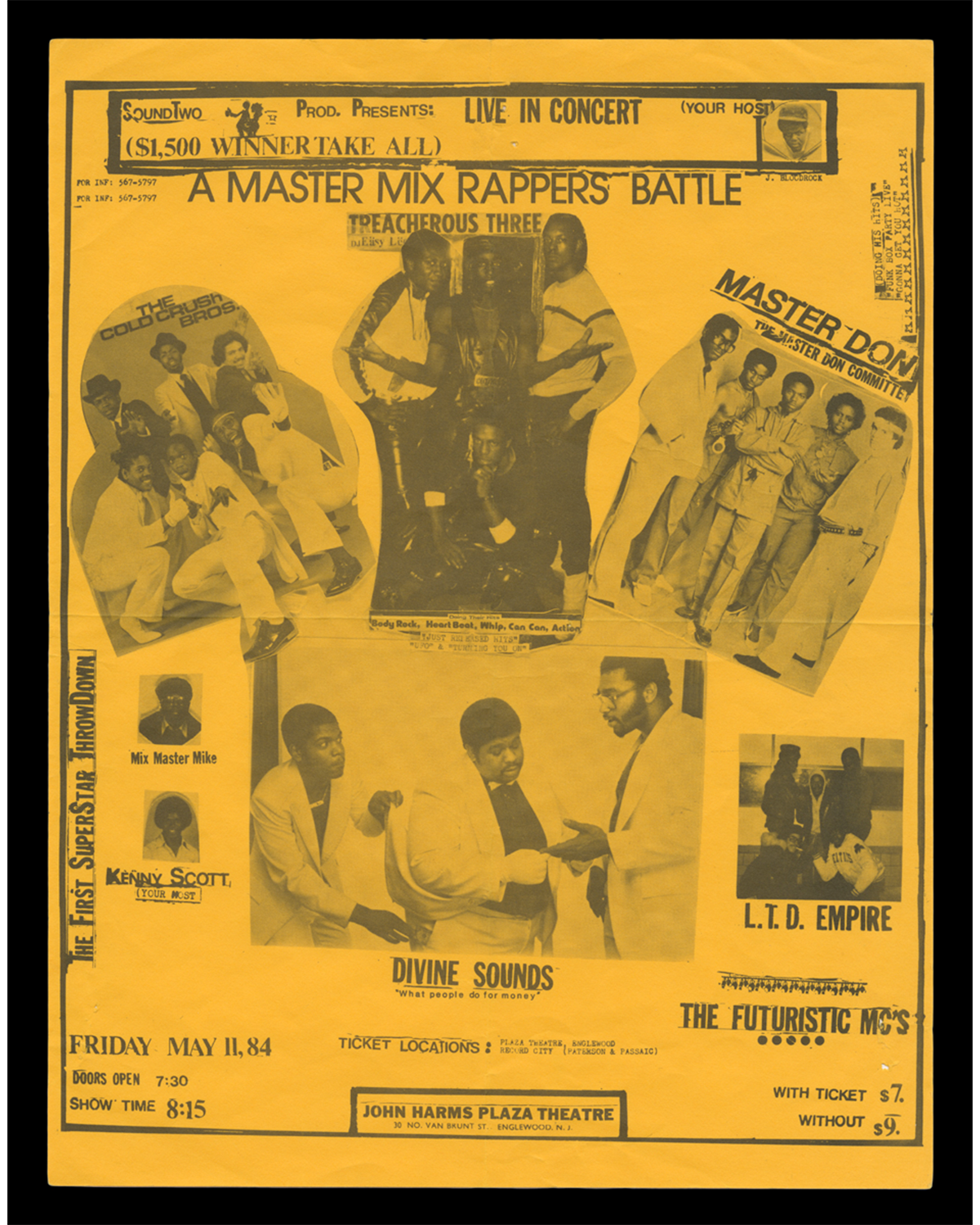

"A Master Mix Rappers Battle," 1984. / THF721983

"A Master Mix Rappers Battle," 1984. / THF721983

What is now called rapping has deep roots in Black American culture and in other parts of the African diaspora. Everyone from jazz band leader Cab Calloway to the poetry collective The Last Poets spoke rhythmically over music in styles similar to hip-hop emcees. Caribbean "toasting" songs were also foundational to rapping; in "toasting," Jamaican DJs spoke in a sing-song tone over the records that they played at parties or on the radio. Traditions like these influenced DJs, including Kool Herc, to bring their friends, e.g. Coke la Rock and Clark Kent, to join them and rap while the DJ played music.

These early emcees were masters of ceremony at parties; they would rhyme over a few bars of music to hype up a crowd or tell someone that their car was double parked. This is why many early rappers included the moniker "MC" in their names. From this came a culture of braggadocious and sometimes insulting raps pointed at rival emcees who played at the same events or venues: battle rapping. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, rap battles, like "Master Mix Rappers Battle," were promoted to draw crowds to clubs. The crowds' response — applause, cheers, jeers, and boos — determined the winners of these battles. Some of the top-billed emcees who participated in the "Master Mix Rappers Battle" were or would soon become famous. The Cold Crush Brothers were already legendary by 1984. The crew battled the Grand Wizzard Theodore and the Fantastic Five at Harlem World in 1981. This performance is considered one of the first important rap battles in hip-hop history. Bootleg recordings of the battle were distributed among young hip-hop enthusiasts and inspired aspiring emcees such as Darryl McDaniels, DMC of Run DMC. In 1982, the Cold Crush Brothers re-created the Harlem World battle for the big screen in a film called Wild Style.

Members of the Treacherous Three influenced the changing sound of hip-hop over the next decade. Emcees Kool Moe Dee and Spoonie Gee were forefathers of the subgenres New Jack Swing and Gangsta Rap, which both grew in popularity during the late 1980s and early 1990s.Master Don and the Committee — sometimes billed as Masterdon Committee or Death Committee — did not achieve the same level of fame as their competitors. After scoring a New York City radio hit with their song "Funkbox Party" in 1983, their success remained mostly localized. However, they were innovators as one of the first mixed-gender rap crews with the inclusion of DJ Master Don's sister, Pebblee Poo.

"A Birthday Party for the Lovin' Trouble," 1983. / THF721984

"A Birthday Party for the Lovin' Trouble," 1983. / THF721984

Hip-hop is not just a music genre; fashion has been baked into the culture since the beginning. There are many examples of the symbiotic relationship between hip-hop and style. Artists have started fashion labels like Roc-a-Wear, and emcees often call out their favorite brands in their lyrics like in "My Adidas" by Run DMC.

Early in hip-hop's development, there seemed to be a divide in the culture about how to dress. On the one hand, the young working-class Black and Puerto Rican audience would wear street styles from brands that they had already in their closet, like Kangol or PRO-Keds. They might add personalized touches to their outfits such as permanently creasing their jeans. If they were a dancing b-boy or b-girl, they might rep their dance crew by wearing uniform clothes.

PRO-Ked "69ers" Shoes, Worn by DJ Kool Herc, circa 1980. In hip-hop's early days, PRO-Ked basketball shoes were the sneakers of choice for DJs, emcees, and audiences alike. PRO-Ked shoes were so common among Black and Hispanic youths in the Bronx that the shoes were nicknamed “Uptowners,” referring to the borough’s location./ THF191954

PRO-Ked "69ers" Shoes, Worn by DJ Kool Herc, circa 1980. In hip-hop's early days, PRO-Ked basketball shoes were the sneakers of choice for DJs, emcees, and audiences alike. PRO-Ked shoes were so common among Black and Hispanic youths in the Bronx that the shoes were nicknamed “Uptowners,” referring to the borough’s location./ THF191954

On the other hand, there was the influence of discotheque culture. In the disco clubs, it was common for people to dress in their finest and most eye-catching apparel. For those who bridged the disco and hip-hop worlds, the glamorous get-ups were more appealing. DJ Hollywood — one of the first people to rap rhythmically over music and influence early emcees — enforced a strict dress code wherever he performed. At a DJ Hollywood party, streetwear and sneakers were strictly prohibited.

Women's "Lombada Hi Bright" Pumps, 1980-1990. Low-heeled shoes like these were popular from the 1970s until the 1990s as nightclub culture developed. The lower center of gravity made the shoes easier to dance in. They exemplify what a fashionable partygoer might wear. / THF65284

Women's "Lombada Hi Bright" Pumps, 1980-1990. Low-heeled shoes like these were popular from the 1970s until the 1990s as nightclub culture developed. The lower center of gravity made the shoes easier to dance in. They exemplify what a fashionable partygoer might wear. / THF65284

During the 1980s, many emcees and DJs embraced luxury fashion as they gained fame. For example, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five performed in elaborate leather outfits, purported to cost over $1,000 each. One fashion pioneer, Harlem-based Daniel "Dapper Dan" Day, noticed this trend and opened his boutique Dapper Dan of Harlem in 1982. He designed custom clothes made of leftover materials from haute couture brands like Louis Vuitton. Dapper Dan blended street fashion and high fashion; he prominently displayed brand name logos on his clothing and innovated the concept of "logomania" in fashion.

These three flyers represent just some of the many stories that transformed hip-hop into the cultural phenomenon it is today. If you are interested in seeing more party and event flyers from this era of hip-hop, check out Cornell University Library's hip-hop collection.

Kayla Chenault is the Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

On November 8, 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered electromagnetic radiation, or invisible light, which he dubbed x-rays; immediately they became a huge fad, used for everything from photographic filters to miracle cures for a variety of ailments. X-rays bridged the gap between the public's interest in scientific advancement and commerce. One fascinating artifact in The Henry Ford's collection demonstrates the X-ray craze well: a shoe-fitting fluoroscope.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. X-Ray Shoe Fitters, Inc., a subsidiary of the Adrian Company of Madison, Wisconsin, was one of largest manufacturers of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and made this X-ray. / THF803832

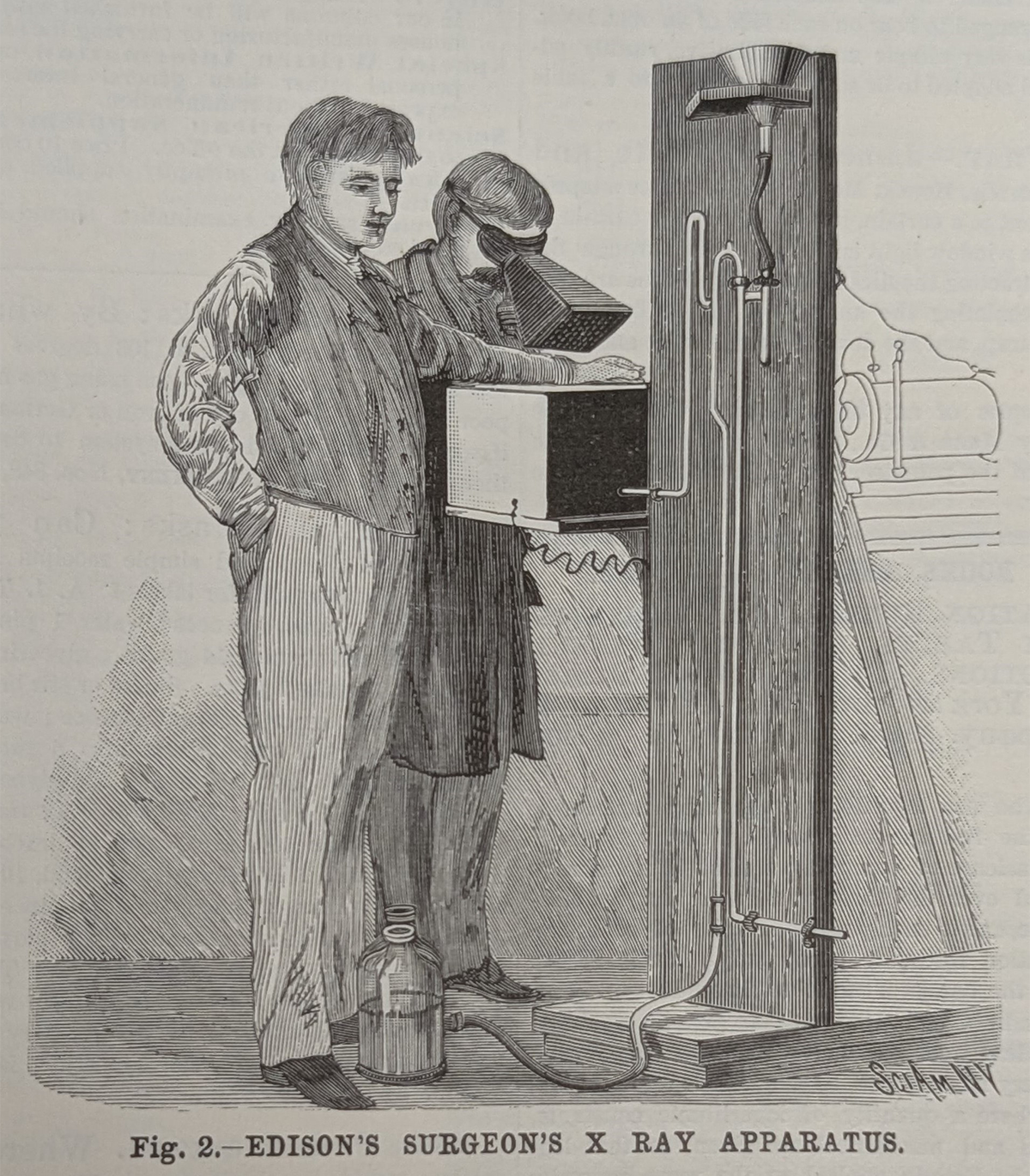

Fluoroscopes are real-time, continuously moving X-ray images — like an X-ray movie. Thomas Edison created the first commercially available fluoroscope in 1896 by adapting the basic principle of static X-rays.

Illustration from Scientific American announcing Edison's fluoroscope in April 1896. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

X-rays are beams of invisible light moving in short wavelengths, which pass through objects and create negative images of them on a fluorescent screen. What you see in the negative image depends on how much radiation an object can absorb. More dense objects like bones absorb more radiation, so they show up as white on an X-ray picture; less dense objects like muscle tissue absorb less radiation, so they show up as dark on an X-ray picture. Edison's fluoroscope allowed people to look at their bones in real-time when they placed their bodies between a cathode tube that made X-rays and a fluorescent screen that displayed the images created.

Box of fluoroscope Slides, 1895-1905. / THF157985

In the early days of fluoroscopy, they were primarily used in hospitals or as novelties. In 1919, Jacob Lowe, owner of a Boston-based X-ray laboratory, filed a patent for the first fluoroscope explicitly for fitting shoes. Lowe saw the problem of ill-fitted shoes causing discomfort in the short term and foot deformities in the long term; his machine would allow the customers to see their feet inside of their shoes and would presumably prevent future issues.

Shoe-fitting fluoroscope, circa 1936. To use a shoe-fitting fluoroscope, customers would stand on this side of the X-ray and put their feet in the chamber at the bottom. / THF803822

To use Lowe's fluoroscope, customers placed their feet on the enclosed platform where the X-ray tube was and looked through one of the fluoroscope's viewfinders to check their feet on the fluorescent screen. The three viewfinders also allowed simultaneous observation: for example, a salesperson, a child trying on shoes, and the child's parent.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. A customer could see a fluoroscope of their feet from the viewing chamber above. / THF803831

The patent was granted in 1927, and Lowe assigned the patent to the Adrian Company in Madison, Wisconsin, which began manufacturing shoe-fitting fluoroscopes in 1922. For the next thirty years, shoe-fitting X-rays became ubiquitous in shoe stores across the world.

Did X-raying feet actually help customers and store employees fit shoes? In the 1990s, a former shoe shop clerk was interviewed about shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and revealed that the machines did not help him properly size customers. Additionally, he did not know any salespeople who felt the machine truly helped them. Shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were essentially a marketing gimmick that incentivized customers to buy shoes.

During the 1920s, businesses began to focus on ways to drive consumer habits through driving demand. For example, Charles Kettering of General Motors championed the idea of selling "newness" to customers in his 1929 essay "Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied": "If everyone were satisfied, no one would buy the new thing because no one would want it […] You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times." Kettering's philosophy was pivotal to understanding why fluoroscopes were popular among shoe sellers. Even the Adrian Company's shoe fitting X-ray manual touted the unverified statistic that 75% of people wore shoes too small for them and therefore needed new shoes. That statistic could be repeated to customers to bolster dissatisfaction and drive sales. Additionally, there was a perception that using fluoroscopes was a necessary form of consumer safety. The "see for yourself" nature of the fluoroscope created the illusion of an "objective" way for salespeople to determine if new shoes were necessary.

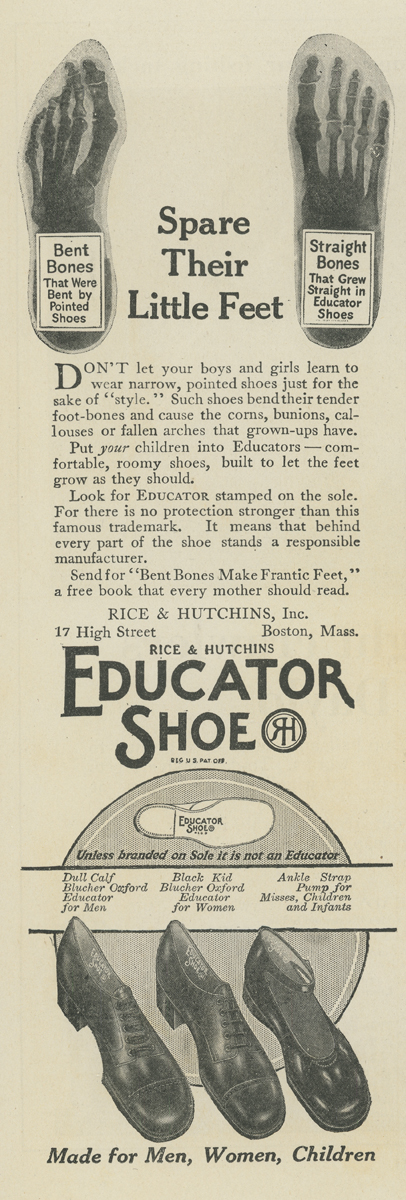

"Spare Their Little Feet," 1917-1921. / THF723224

The fluoroscopic sales tactic was used on women especially by playing into the idea of "scientific motherhood." At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an increasing expectation that women needed the latest technological advancements and advice to raise their families correctly. The concept of "scientific motherhood" was utilized to great effect in advertising, where companies marketed their products with sometimes-dubious claims of "expert approval" or "rigorous scientific testing."

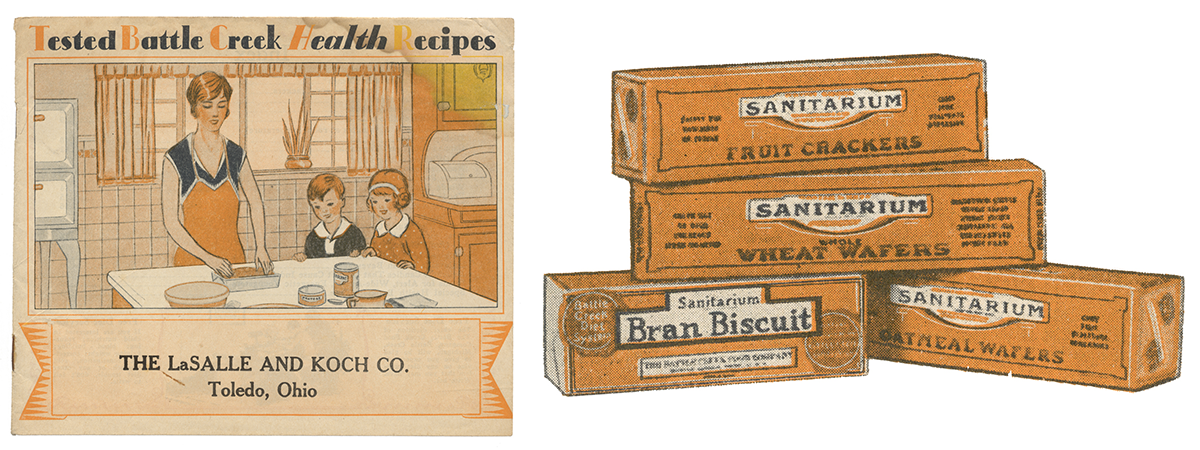

Tested Battle Creek Health Recipes, 1928. This recipe booklet is a great example of scientific motherhood in advertising. The booklet was sold along with crackers and cookies but used words like "health," "sanitarium," and "tested" to imply that the food was healthy for families like the one shown on the cover. / THF17004 and THF17005

With the fluoroscope, shoe store owners played into the medicalization of mothering. Salespeople often recommended annual or even quarterly foot X-rays for children in the way doctors might recommend yearly physicals. Repeat X-rays created repeat customers.

Additionally, kids loved fluoroscopes! Stores would advertise their shoe-fitting fluoroscopes alongside other child-friendly customer perks like balloons, contests, and candy.

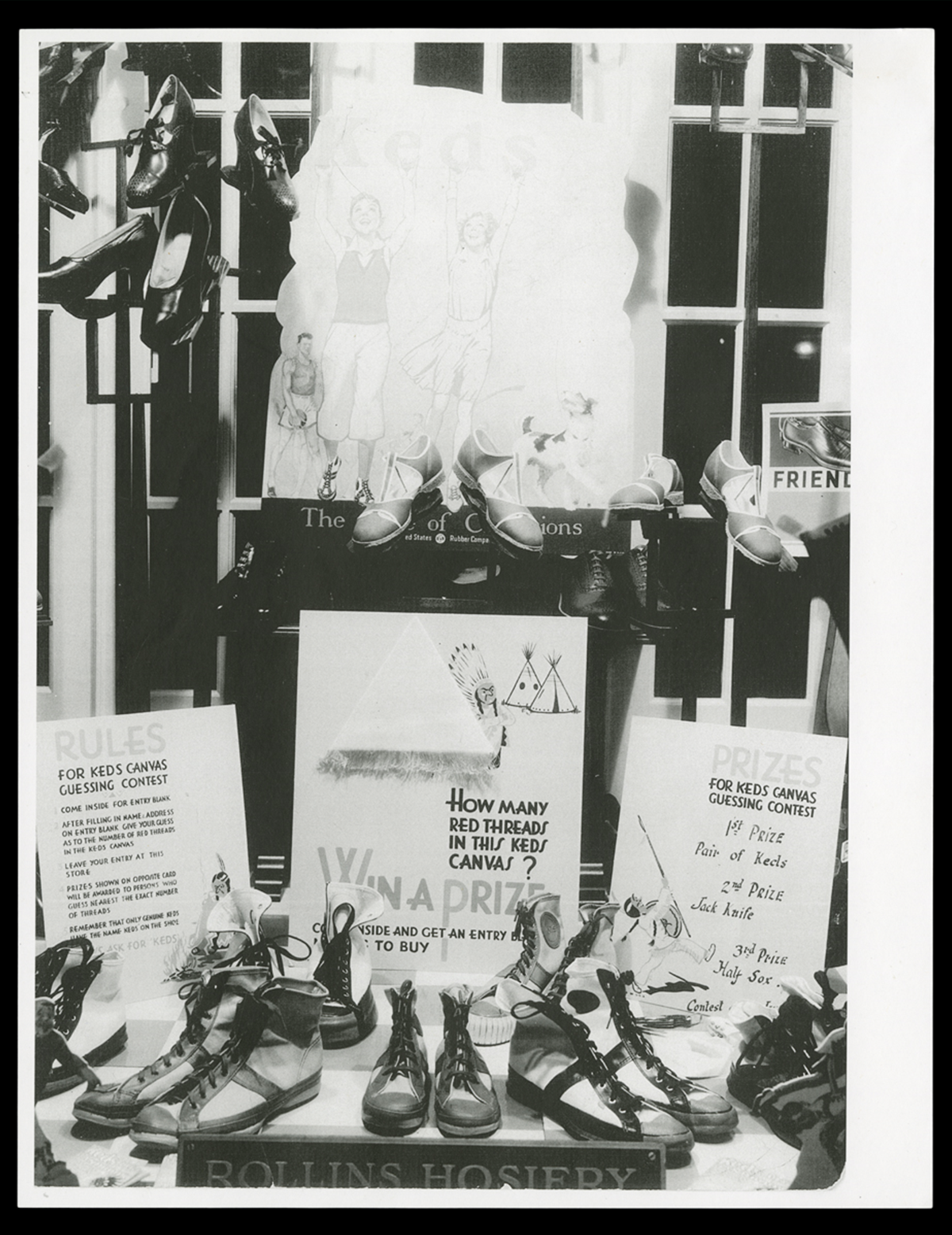

Keds window display at the Campbell Boot Shop, Charlevoix, Michigan, circa 1930. This shoe store used window display contests to attract young customers with the possibility of brand new shoes. / THF723228

Until the late 1940s, fluoroscopes were used everywhere from first aid stations on job sites to quality control inspections on orange tree farms. However, the lack of regulation for radioactive machines endangered people. Several high-profile incidents eroded the public's trust in fluoroscopy. For example, between 1941 and 1943, 57 California Shipbuilding Corp. workers received mutilating radiation injuries after using the company's first aid fluoroscope. This lack of regulation also affected shoe fitting X-rays. A 1948 study of Detroit-area shoe stores showed that over 20% of stores' fluoroscopes produced 16 to 75 röntgens — the measure of radioactive discharge — per minute. At the time the maximum radiation exposure recommendation was .3 röntgen per week.

X-ray tube, circa 1915. Vacuum tubes like this are used to produce X-rays in fluoroscopes and other forms of radiography. / THF174376

In 1950, Carl Braestrup, senior physicist for New York City hospitals, was one of the first health officials to warn the public that shoe-fitting fluoroscopes could cause radiation burns and leukemia, especially in children. That same year, city health officers in Los Angeles reported that shoe-fitting fluoroscopy caused abnormal bone growth in children. But shoe stores were initially reluctant to get rid of their machines; Los Angeles shoe store owners claimed that parents' demand for X-rays drove them to keep them. It took until 1957 for Pennsylvania to become the first state to ban shoe-fitting fluoroscopes.

In many ways, the shoe X-ray represents a time when science and commerce seemed to go hand-in-hand but went toe-to-toe instead. Innovations, like the X-ray, were used to turn profits but also harmed the public.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope being photographed for digitization. / Photo by Staff of the Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson: Saxophonist

Music is a part of the Jackson family story, from the piano lessons that first brought young Richie Jean Sherrod soon-to-be-Jackson and young Coretta Scott soon-to-be-King together to the family's music room. In fact, Dr. Sullivan Jackson played tenor saxophone prior to his career as a dentist serving Selma's Black community. Dr. Jackson's time as a musician in the mid-1940s to the early 1950s allowed him to participate in Black American music cultural changes.

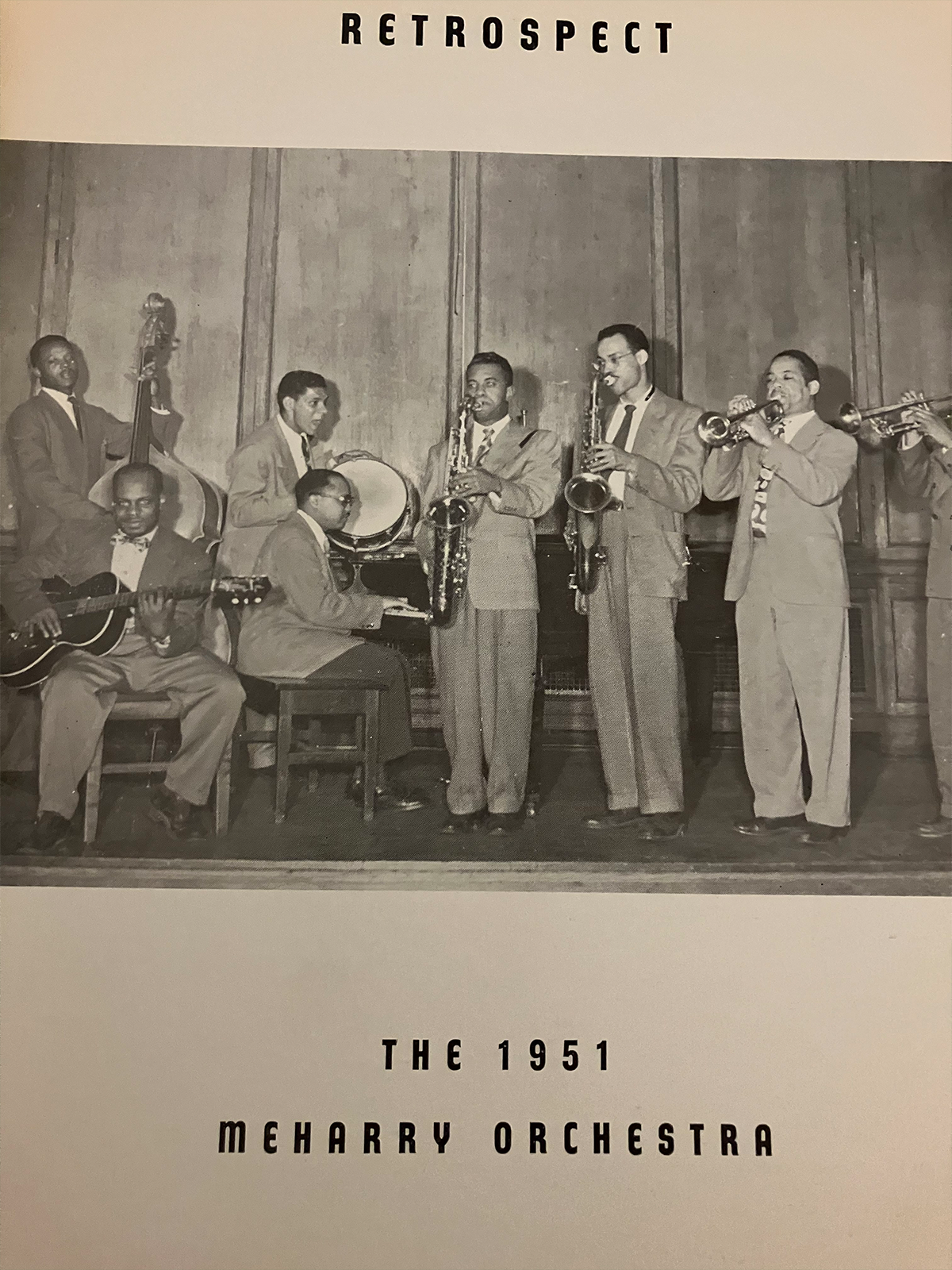

This picture of the Meharry Medical College Orchestra from the 1951 Meharrian yearbook shows Dr. Sullivan Jackson (center) playing the saxophone as a third-year medical student. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

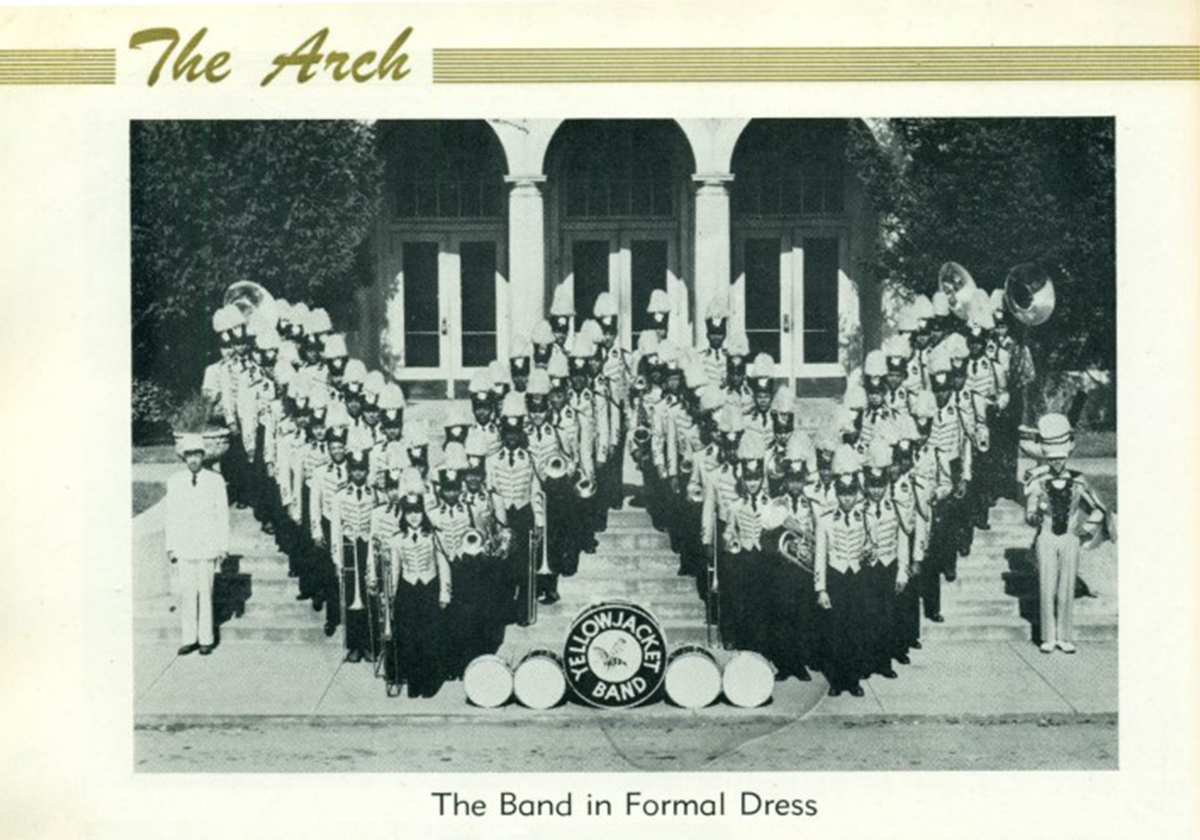

Following service in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, Sullivan Jackson enrolled at West Virginia State University (WVSU), one of 107 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). He joined the WVSU Yellow Jacket collegiate band as a saxophonist in the mid- to late1940s, a time when marching band culture at HBCUs was evolving.

Collegiate marching bands originate from U.S. military bands that played music to boost soldiers' morale and keep tempo during long marches. Starting in the 1840s, American colleges founded marching bands on their campuses and in the 1890s, Tuskegee Institute — now Tuskegee University — became the first HBCU to have a band. At most colleges marching bands were a part of Reserve Officers' Training Corps programs during this time. For example, Tuskegee's marching band was a part of the school's military science department — not the music department — prior to 1931.

Tuskegee Institute Football Pennant, 1920-1950. / THF157606

World War I changed the type of music that bands played at HBCUs. Between 1917 and 1918, the U.S. Army mobilized 27 new Black regiments, all of which established regimental bands. The approximately 1,000 Black musicians mustered out for service in these bands included collegiate conductors and music professors from HBCUs. While standard military marches were a part of the regimental bands' repertoires, they also played popular music such as Missouri-style ragtime and New Orleans-style jazz. After the end of the war, the veterans returned to their jobs at HBCUs and conducted collegiate bands to play both march music and popular songs as they had during the war.

This evolution reached a crescendo in the mid-1940s while the future-Dr. Jackson was at WVSU. In 1946, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College — now Florida A&M University — hired William P. Foster to direct the school's marching band. Foster recruited returning GIs, professional musicians and high school students to play in FAMU's band. Foster's musicians performed solely popular music, building on the legacy of Black regimental bands during World War I. They also marched in elaborately choreographed and physically demanding routines that played well in newsreels and later on television. Over the following years, other HBCU bands adopted Foster'sflair for pageantry and emphasis on contemporary music and choreographed spectacles. Even Dr. Jackson's own West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket marching band posed in a W-shaped formation in the school's 1948-49 yearbook, demonstrating this cultural change at HBCUs. This legacy remains the gold standard of band performance at HBCUs today.

West Virginia State University Yellow Jacket Band, circa 1948. / Via West Virginia State University Drain-Jordan Library

After graduating from WVSU, Sullivan Jackson pursued a degree in dentistry from Meharry Medical College in Tennessee. During that time, Dr. Jackson played saxophone in a band called the Doctors of Rhythm. The Doctors of Rhythm toured in what became known as the Chitlin' Circuit.

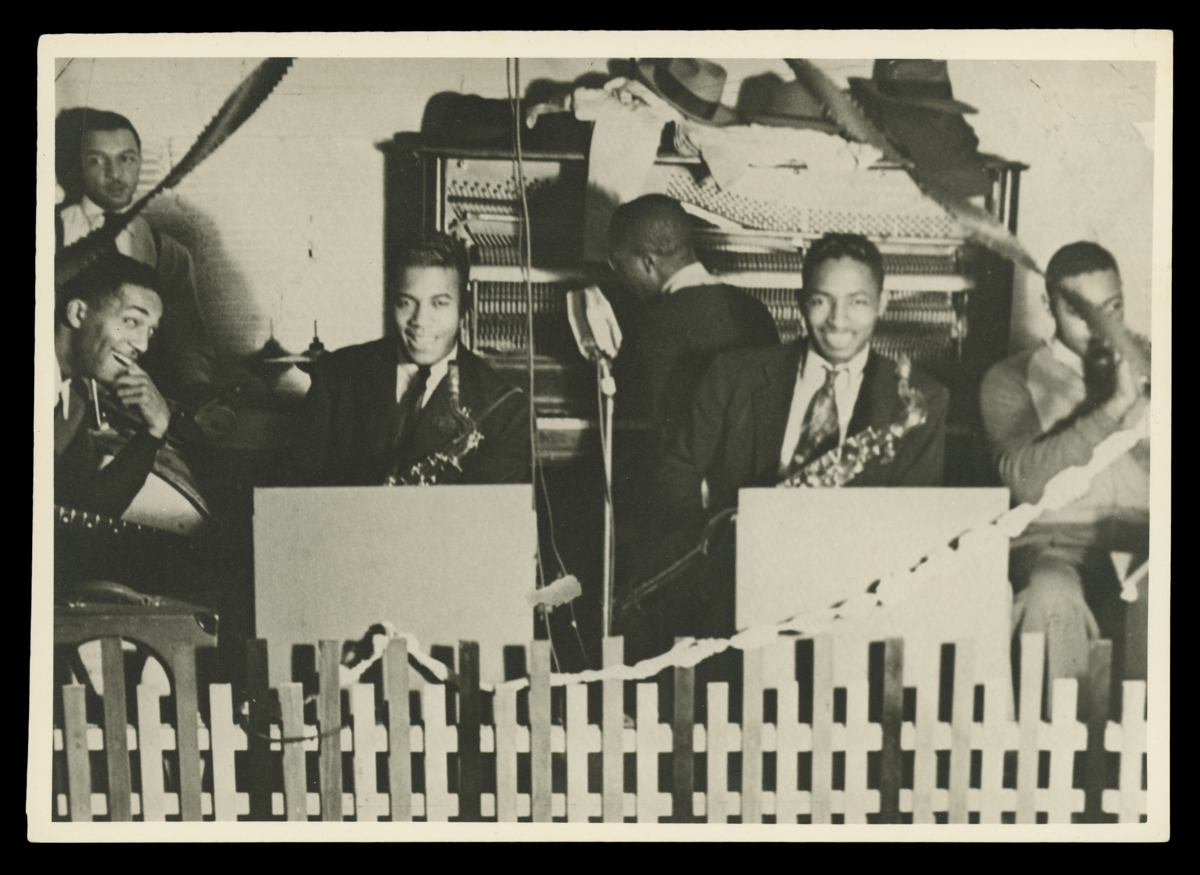

Sullivan Jackson with His Band, Date Unknown. Sullivan Jackson is seated second from the left holding his saxophone. / THF719998

Exclusionary segregation practices in the United States meant that traveling Black entertainers could not go to certain venues. In the 1920s, the only booking agency that served Black musicians, comedians, dancers or singers was the Theater Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.). However, performers who were booked through T.O.B.A. paid their travel expenses out of pocket and could only play at White-owned T.O.B.A.-affiliated venues.

When the Theater Owners Booking Association folded due to financial collapse in the 1930s, an informal network of Black booking agents and venues for Black clientele arose in its place. Performers now had the freedom to play where they liked: from large theaters like the Apollo in Harlem to the hole-in-wall juke joints in small towns like Hobson City, Alabama. This network was later called the "Chitlin' Circuit." The name is a riff on "Borscht Belt" venues that primarily booked Jewish American entertainers for Jewish American audiences; it is also a reference to chitterlings, a controversial staple of Southern American cooking.

The Orioles Music Group inside Fox Brothers Clothier, Chicago, Illinois, 1942. The Orioles were a pioneering rhythm and blues group that performed on the Chitlin' Circuit in the 1940s and 1950s. / THF184199

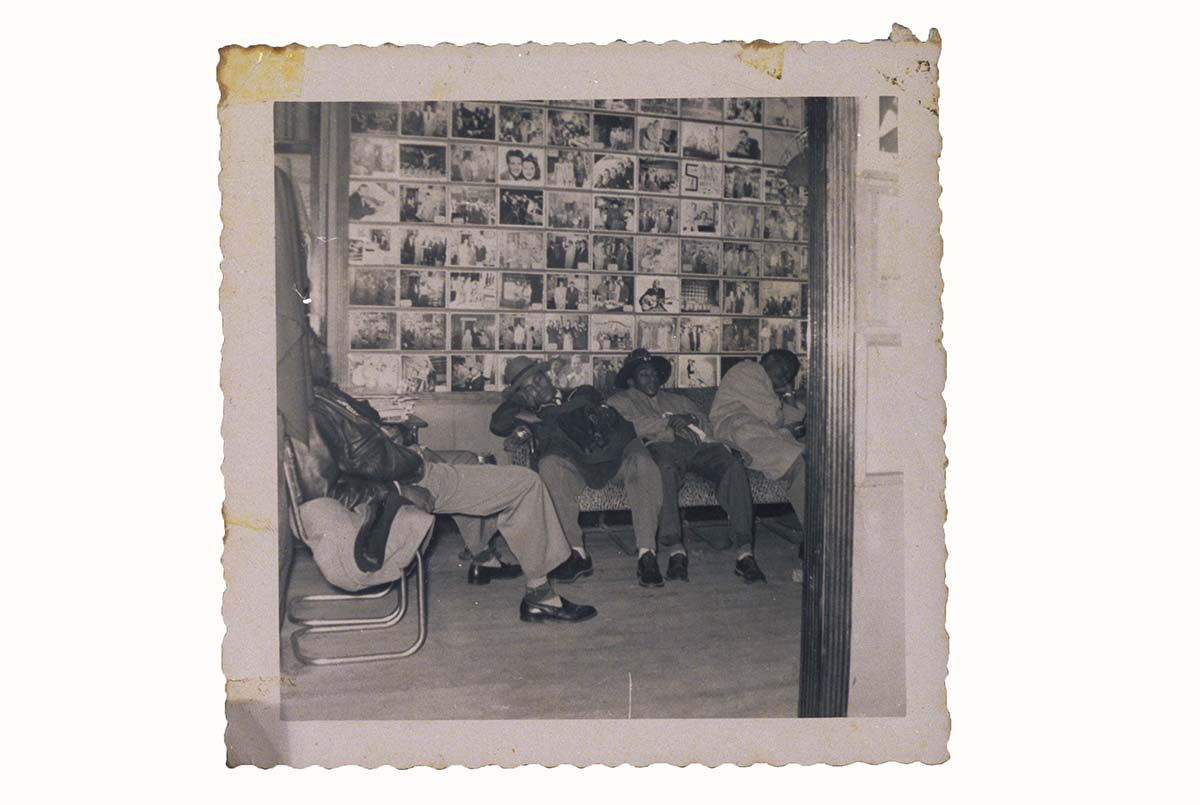

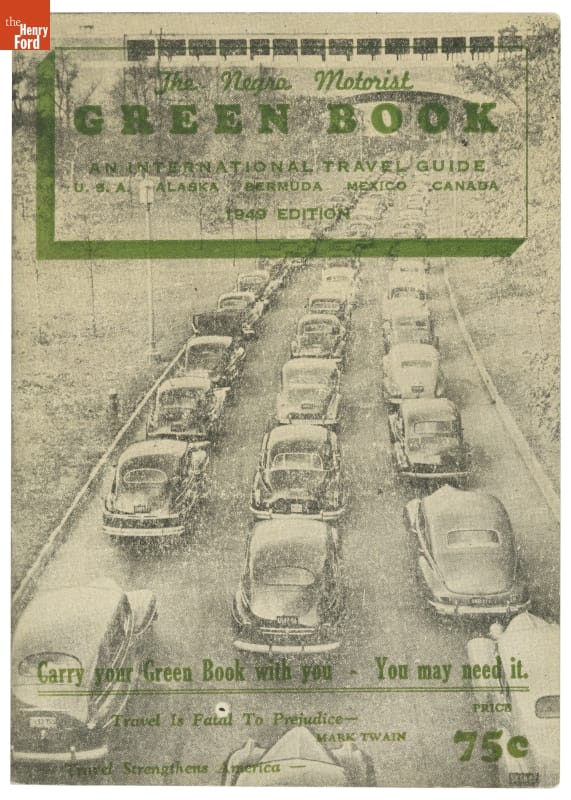

Performers like Sullivan Jackson appreciated the freedom afforded to them on the Chitlin' Circuit, but faced challenges on the road. Johnny Shines, a blues musician who toured the Circuit in the 1940s, described most venues as "rough" places where drinking, gambling, and fighting were common. Chitlin' Circuit audiences were notoriously harsh critics; the Apollo Theater emcee, "Sandman" Sims, used props like a hook or broom to kick acts off stage if the crowd booed them. Most venues paid the artists very little; sometimes payment came in the form of a hot meal instead of any money. Even traveling between shows could be perilous. Many Chitlin' Circuit performers had to drive all night to find safe lodging and were refused service while on the road. With Jim Crow laws in the South and thousands of sundown towns throughout the country, performers had to rely on resources such as the Negro Motorist Green Book and the hospitality from the communities they played in for travel, lodging, and food.

"Negro Motorist Green Book, An International Travel Guide," 1949. / THF77183

For a lucky few — like Chitlin' Circuit veterans Tina Turner, James Brown, Richard Pryor, or Jimi Hendrix — touring the Circuit was excellent training for their later famous careers. But even a short-lived entertainment career like Dr. Sullivan Jackson's provided Black performers with an opportunity to grow as artists and work within their own communities.

After graduating from Meharry Medical College, Dr. Sullivan Jackson became a dentist in Selma, Alabama, started his family and took part in the struggle for civil rights. But his connection to the music world was not severed. Among the Jackson family's many and frequent guests, traveling musicians — some of whom he played with — were also welcomed into the home. And Dr. Sullivan Jackson kept his tenor saxophone over the years and it is now part of the collection of The Henry Ford.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson's Selmer Mark VI Tenor Saxophone, 1968. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The Hair-Raising History of Women's Body Hair

In 1992, Jill Shurtleff, a designer with the Gillette Razor company, challenged the idea that women’s razors should be limited to the repackaging of men's razors with a different color scheme. Considering how women shave, where they shave and why they shave, Shurtleff created the Sensor for Women razor with a wider handle for better grip and a blade cartridge designed to get into hard-to-see crooks of the body. She might not have known it at the time, but her work intersects with a complex history of body hair removal. Women's relationship with their body hair has evolved tremendously over the past two centuries. Why and how women choose to remove it — or not remove it — reflects changes in technology, politics, fashion, and culture that still impact people today.

The Sensor for Women Razor from Gillette was the first razor designed for women’s shaving needs specifically in mind. / THF803274

Before the mid-1800s, removing so-called "superfluous hair" — the term used for body and facial hair — was rare but could be dangerous. For women who suffered from hirsutism, extra hair growth on the face, books provided homemade depilatory recipes. These remedies often contained caustic and poisonous ingredients such as barium hydroxide, quicklime, and arsenic, but the danger of these chemicals was unknown at the time. Following the American Civil War, electricity transitioned from being a scientific fascination to an everyday utility, and many turned to its power for their hair removal needs. Electrolysis, using electrified needles to zap hair follicles and make the hair fall out, rose in popularity in the 1870s. The process was expensive, grueling, and painful; inattentive dermatologists could permanently scar their patients’ faces. Later hair removal methods were riskier. One infamous depilatory cream known as Koremlu contained thallium acetate, a main ingredient in rat poison; women reported neuropathic pain, blindness, and even paralysis after using Koremlu. In the 1920s, hair salons installed x-ray machines to rid women of facial hair; women exposed to the radiation from these machines experienced ulcerated sores and cancerous tumors on their faces. However, x-ray machines for hair removal processes remained popular until the end of the 1940s.

"Sheer" hair remover, circa 1928-1935. This depilatory cream used the now banned substance, Mercurochrome, a compound of mercury and bromine. / THF802140

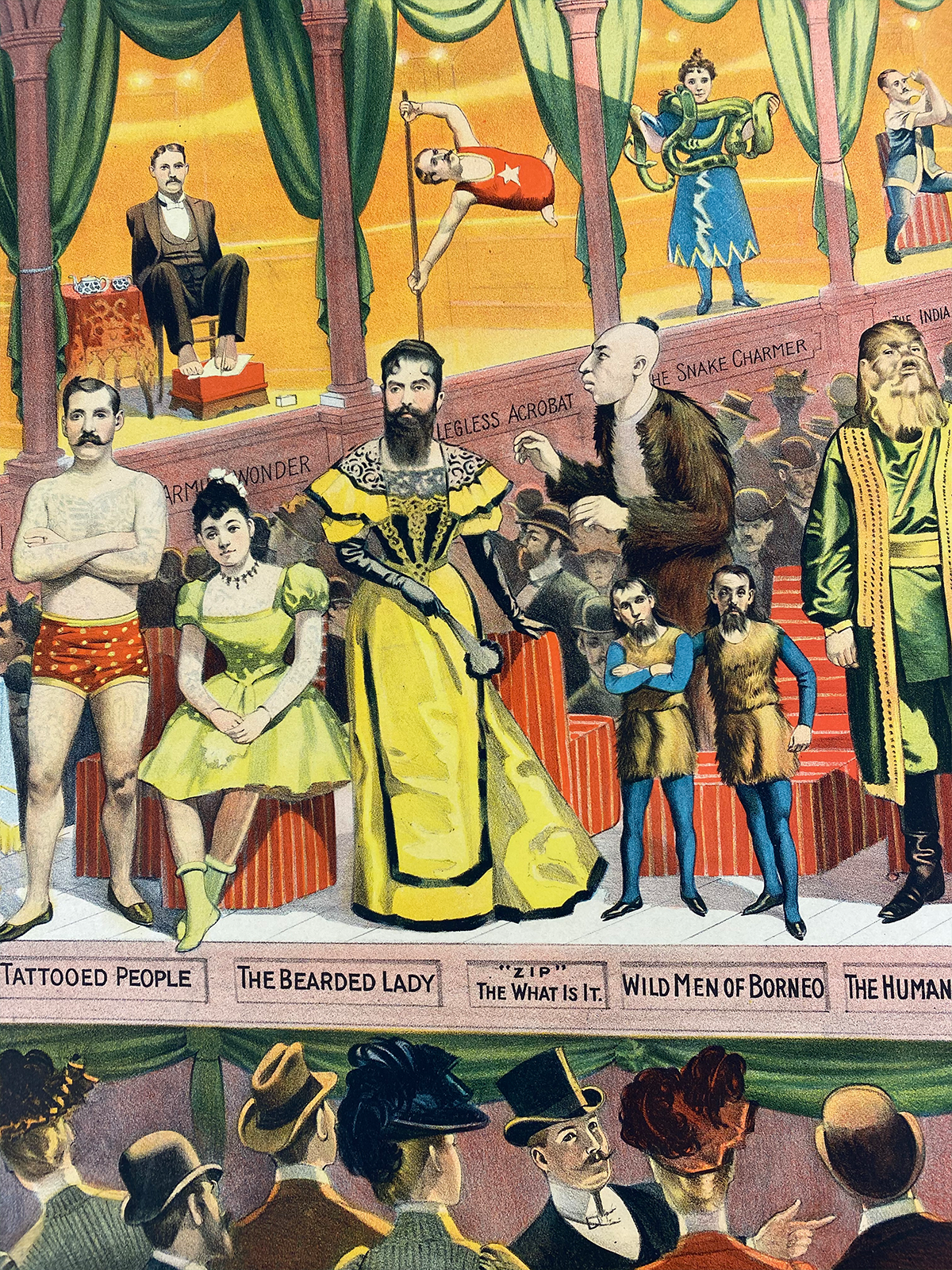

Women risked their lives for smooth skin, because the stakes of hairiness were not merely aesthetic. Some women with extreme hair growth on their faces and bodies were put on display for circus entertainment or studied as evolutionary anomalies, practices that caused great harm. Early electrolysis practitioners reported their patients were nearly suicidal due to their hairiness. Prominent psychologist and eugenicist, Knight Dunlap, wrote in a 1921 book that inherent hairlessness was evidence of a woman's fitness for partnership and motherhood. Being hairless was not just about beauty standards; it was seen as proof of one's humanity.

This 1898 Barnum and Bailey’s circus poster shows a woman with hirsutism who was placed on display. / 35.784.116 Image by Kayla Chenault.

Even with these pressures to be hairless, true ubiquity of hair removal came with a change in clothing styles. During the first three decades of the 20th century, women's fashion was revolutionized, and more of the body was on display than ever before. Haute couture designers, such as Paul Poiret or the Callot sisters, created free-flowing, loose-fitting garments inspired by clothing from Ancient Greece, Japan, and the Middle East. These styles came in vogue with fashion-conscious upper-class women in the early 1910s and trickled down into the mainstream during and after the First World War.

Wedding Dress (1918). This Lucile Ltd. wedding dress exemplifies the flowing, popular couture style. / THF29590

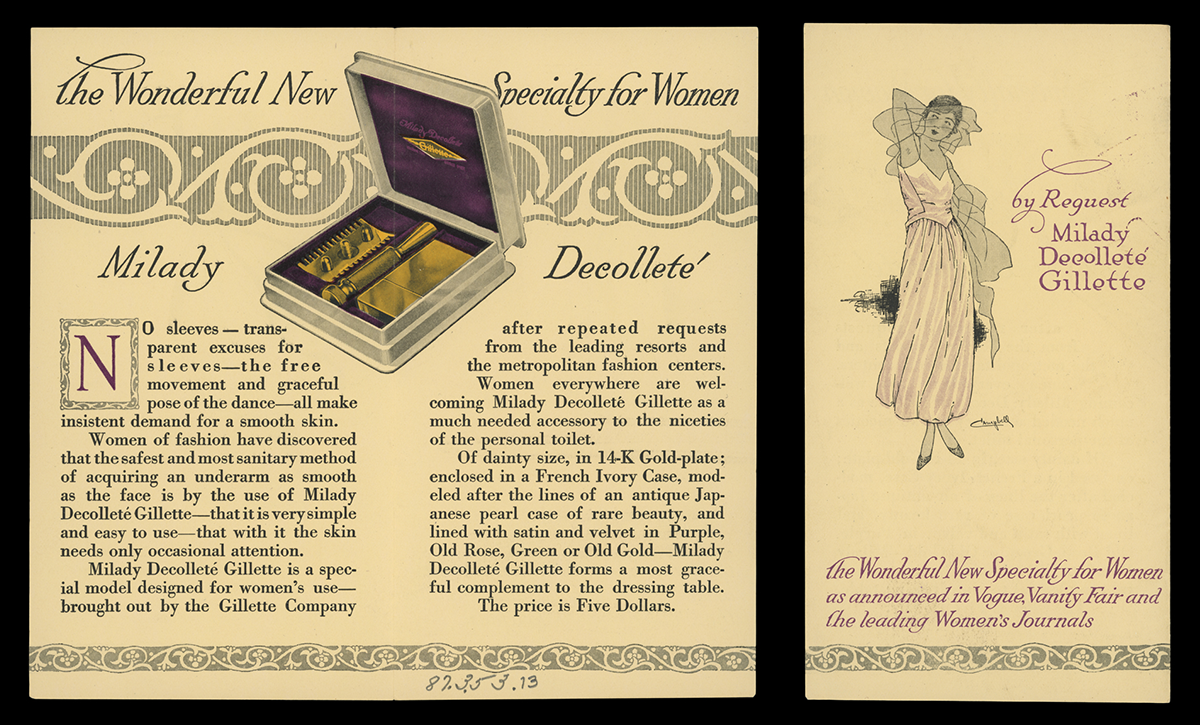

These new styles featured short or sheer sleeves, or sometimes no sleeves at all, leaving women's underarms exposed. In 1915, the first advertisements touting the merits of removing underarm hair appeared in women's magazines. The ads featured illustrations of women in the latest gowns, showing off their smoothness, which could be achieved with depilatories or razors. Gillette promoted its Milady Décolleté as the first razor advertised for women. The Milady Décolleté razor was not designed for women specifically; it was the Gillette men's razor with a smaller blade head and specialized packaging. But the advertising worked, and women became a profitable market for safety razors.

Trade Catalogue, "By Request, Gillette Milady Décolleté" (1915). / THF720459 and THF720460

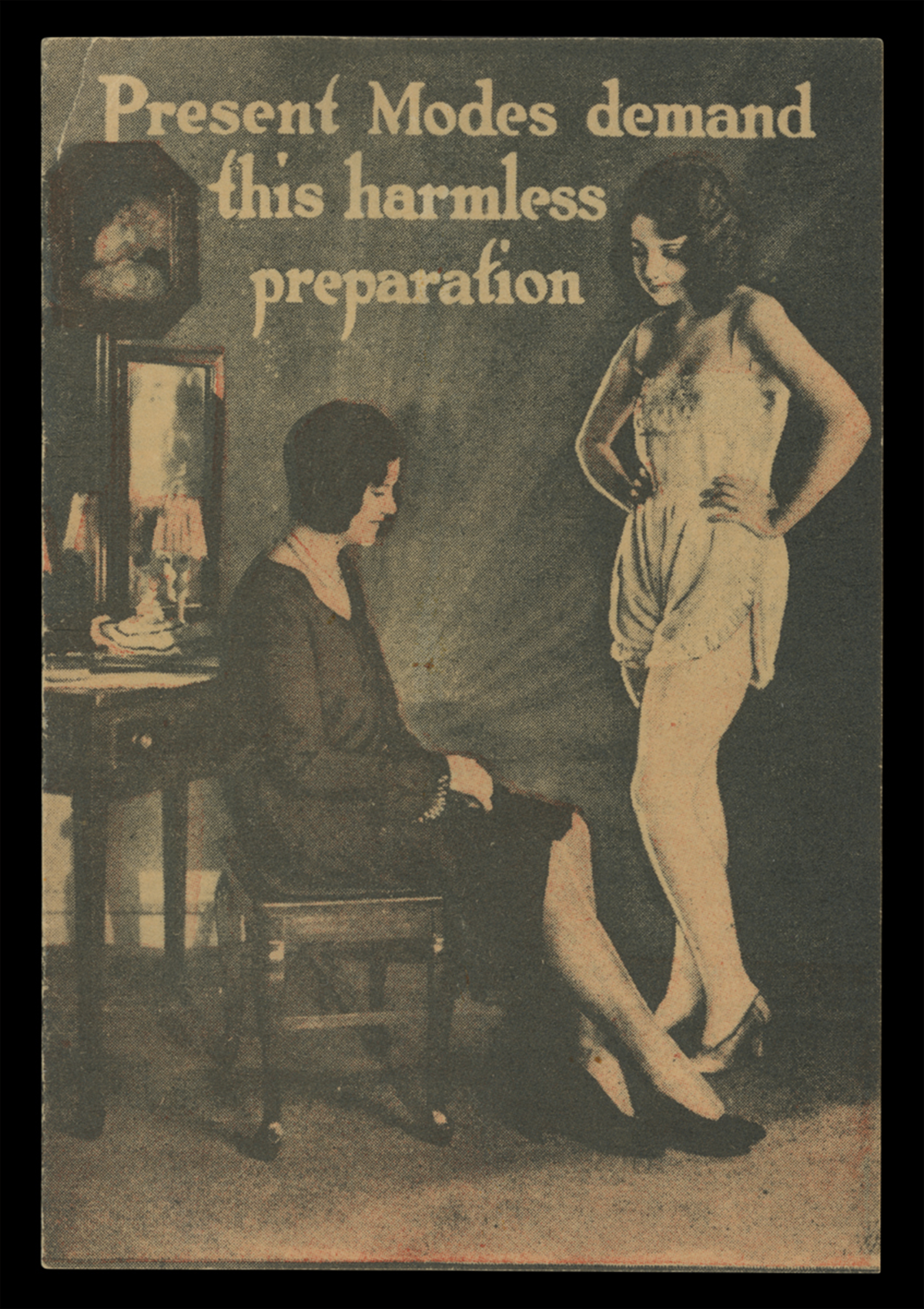

In the 1920s and 1930s, leg hair removal slowly entered the mainstream as popular hemlines exposed more of the leg. Smooth legs were in vogue with young women but caused a minor societal panic over the changing aesthetic. Newspapers ran sensationalist stories about women racing to the doctor after cutting their legs trying to shave them . Some men wrote opinion pieces about disliking the look of smooth legs. The myth that getting rid of one's leg hair made it grow back darker and thicker was a common cautionary tale perpetuated in women’s beauty guides.

Trade Catalogue, "Present Modes demand this harmless preparation," circa 1925. This depilatory cream instruction brochure shows women who have used the cream on their legs. / THF720482

Women fully embraced smooth legs during the Second World War. Wartime rationing programs limited the production of nylon hosiery, leaving women bare-legged. Meanwhile, beautification and personal grooming were considered a patriotic duty for women to boost morale. There was also a lingering belief from earlier eugenic thought that body hairs were "unhygienic" though it had no real scientific basis. Without stockings to cover up these hairs, more women began shaving their legs as a matter of habit.

Photographic print, "Mercury Town Sedan near Suwanee Lagoon in Greenfield Village, July 1941" (1941). / THF134812

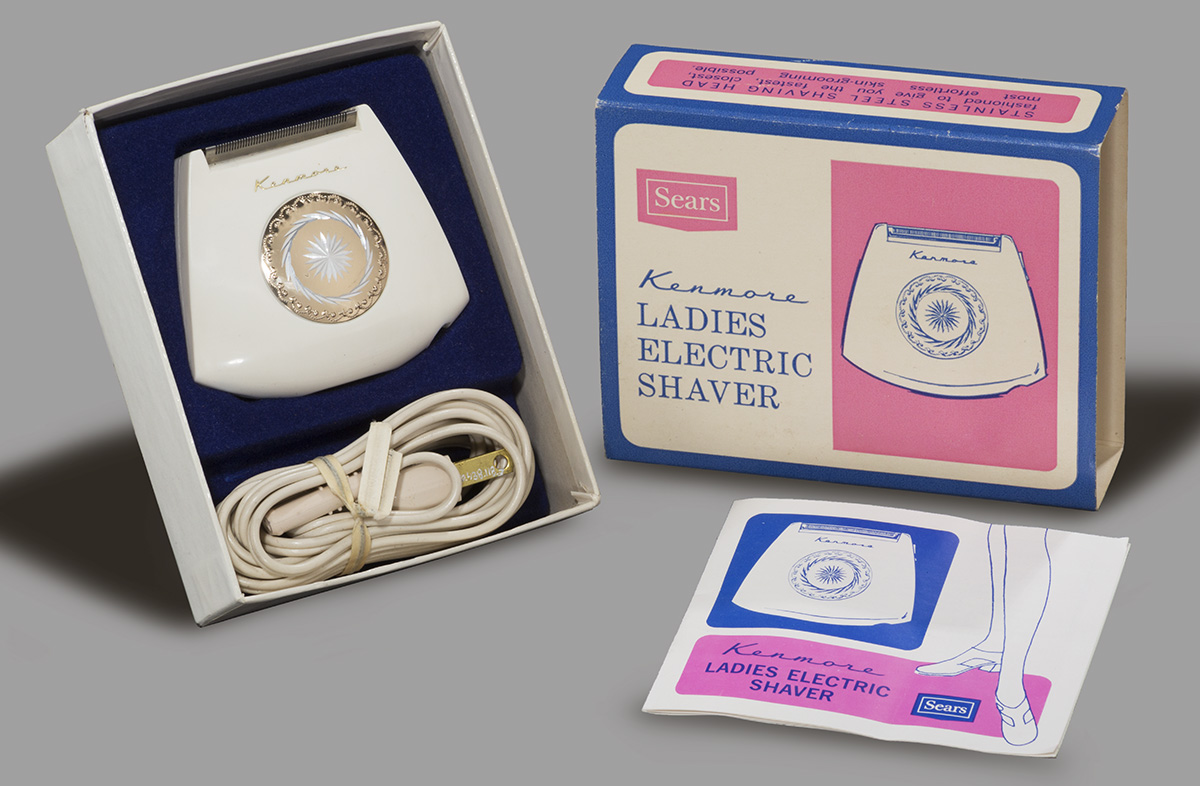

In just a few generations, shaving body hair had transitioned from an advertisement ploy and a newspaper novelty to a rite of passage and a necessity for modern women. By the 1960s and 1970s, it was not a question of if someone should shave their legs and underarms but when they should start. Chances are, if you are a woman in the United States, you have tried to get rid some of your body hair. A 2005 study found that 99 percent of women in the U.S. have shaved their body at some point in their lives.

Sears Kenmore Model 820-93942 Electric Shaver, (1960-1970). Electric shavers were advertised to women for the legs and underarms following the Second World War. / THF172751

However, not everyone removes body hair, and there are myriad reasons why. For example, during the 1960s and 1970s, women's rights activists, particularly those who considered themselves women's liberationists, raised concerns about why women removed body hair at all. Some women decided to grow out their hair as a political statement against objectification, as a testament to their gender and sexual identities, and as a part of a "back to nature" ethos. The non-shavers were relatively few, but there was a visceral reaction to the idea of women not shaving. For opponents of the women's movement, "hairy feminist" was an easy punchline and an affront to femininity itself. Visible body hair became shorthand for the politics of the person who chooses it.

Poster, “The Women’s Liberation Movement” (1970). / THF92260

The dynamic and sometimes dangerous evolution of the very personal relationship women have with their body hair continues to inform people’s daily lives — whether they choose to be bare or hairy.

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.