What We Wore: Movie Costumes

Costume design is more than just providing clothes for actors in a movie. Effective costume design can reveal a character's background, personality, occupation, and even their state of mind. Each costume choice made by a designer—type and style of garment, accessories, details, materials, color—is deliberate, contributing to character development and the overall mood of the narrative.

The costumes below are from films directed by award-winning director Francis Ford Coppola. Coppola’s movies The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979) are often cited among the greatest films of all time.

Costumes provided by American Zoetrope

Through mid-December 2025, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents costumes from the film Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / THF805834

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

As Coppola began production on his spectacular reimagining of the 1897 Bram Stoker vampire novel, he declared that “the costumes will be the set.” His goal: visually exciting costumes that would establish the film’s surreal atmosphere. With the bulk of his budget slated for costumes, he turned to Japanese graphic designer Eiko Ishioka.

Eiko Ishioka, posing with the mask that pairs with Dracula’s armored suit.

Eiko Ishioka, Costume Designer

Eiko Ishioka was not known for costume design when Coppola hired her, a choice that might have seemed a risk. Yet Ishioka’s inventive, avant-guarde style was just what the film needed. And Coppola gave her free rein.

Ishioka—known for crossing or blurring boundaries—incorporated audacious forms, infused symbolic detail, and intertwined elements of Eastern and Western cultures along with steampunk aesthetics into the designs. Ishioka’s extravagant re-envisioning earned her an Academy Award for Best Costume Design.

Tom Waits as Renfield in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / Image by Columbia Pictures.

Renfield

R.M. Renfield—Dracula’s deranged, fanatically devoted servant—has gone insane and is confined to a mental hospital. Renfield suffers from delusions that compel him to eat insects and other living creatures in the hope of obtaining immortality.

The striped design of Renfield’s quilted straitjacket suggests his “prisoner” status. Constructed of rough gray fabric, the costume makes Renfield himself look like an insect!

Gary Oldman as Dracula in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / Image by Columbia Pictures.

Dracula

Ishioka wanted to suggest Dracula’s continued transformation, so she created seven distinctive—and often over-the-top—costumes for him. (In most Dracula-themed films, the fabled vampire had sported a single iconic look defined by a black swirling cape.)

Sometimes less is more. The slender, black pencil coat (shown above), the most visually understated of Ishioka’s Dracula costumes, conveys an ominous sense of undefined danger. While mildly deviant and somehow sinister, the garment provides no overt clues to Dracula’s disturbing need for drinking blood.

Winona Ryder as Elisabeta (later Mina Harker) in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. / Image by Columbia Pictures.

Elisabeta

After being falsely informed that her husband Dracula was killed while off fighting in the Crusades, Elisabeta wears this stunning dress—emblazoned with Dracula’s crest of the Order of the Dragon—as she commits suicide by hurling herself from the castle parapet, setting in motion the Dracula-initiated tragedies to come.

Dracula transforms into a vampire as he waits for the return of his longed-for dead bride—who centuries later he believes is reincarnated in the form of intelligent, yet naïve, Mina Harker.

Earlier this year, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presented costumes from the film Megalopolis. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Megalopolis

Coppola envisioned Megalopolis as a fable, set in a modern world with references to ancient Rome. The deteriorating city of New Rome (New York City) is dominated by a group of elite families, who enjoy lavish lifestyles while ordinary New Romans live in poverty. New Rome must change—causing conflict. Cesar Catilina, a brilliant architect, offers a new vision for the city’s future, the utopian Megalopolis. Mayor Franklyn Cicero remains committed to a status quo of greed and special interests.

Milena Canonero. Image courtesy of Cineberg/Shutterstock.com

Milena Canonero, Costume Designer

Milena Canonero’s costumes for the futuristic Megalopolis reflect Coppola’s vision, merging contemporary design with elements from ancient Rome. A four-time Academy Award winner, the versatile Canonero has developed costumes for the dystopian classic A Clockwork Orange (1971), the psychological horror film The Shining (1980), and the period drama The Cotton Club (1984).

Jon Voight as Hamilton Crassus III in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Megalopolis (2024). / Image courtesy of Milena Canonero.

Hamilton Crassus III

Hamilton Crassus III, head of Crassus National Bank, is the world’s richest man. He can buy anything. With his health and mind in decline, he is easily manipulated by others who have their eyes on his money—and their own interests at heart.

Crassus has “bought” beautiful Wow Platinum—or so he thinks. Crassus’s attire for his wedding to the ambitious Wow shows his great wealth and vanity: a gold-embroidered tuxedo, a cape with lapels that suggest a rich vein of gold, and a gilded “laurel” wreath on his head.

Aubrey Plaza as Wow Platinum in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Megalopolis (2024). / Image courtesy of Milena Canonero.

Wow Platinum

Wow Platinum, a TV personality specializing in financial news, lives for money and power. Wow marries the extremely wealthy—and much older—Hamilton Crassus III. Her plan? To secure control of Crassus and his enormous wealth.

The unscrupulous Wow is a vision in gold in her elegant wedding dress and crown at the over-the-top wedding reception, a decadent celebration complete with circus acts and gladiator wrestling.

Giancarlo Esposito as Mayor Franklyn Cicero in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Megalopolis (2024). / Image courtesy of Milena Canonero.

Franklyn Cicero

Franklyn Cicero, the ultra-conservative mayor of New Rome, has an ineffectual plan for revitalizing the deteriorating city. He’s set his sights on building a casino for the city that will provide immediate tax revenue.

Cicero’s ceremonial formal attire reflects his exalted position as mayor. Yet he must fight to retain power as he spars with idealistic architect Cesar Catilina and his more positive vision—rebuilding New Rome as a utopia.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Vojtěch Kubašta: Beyond Borders

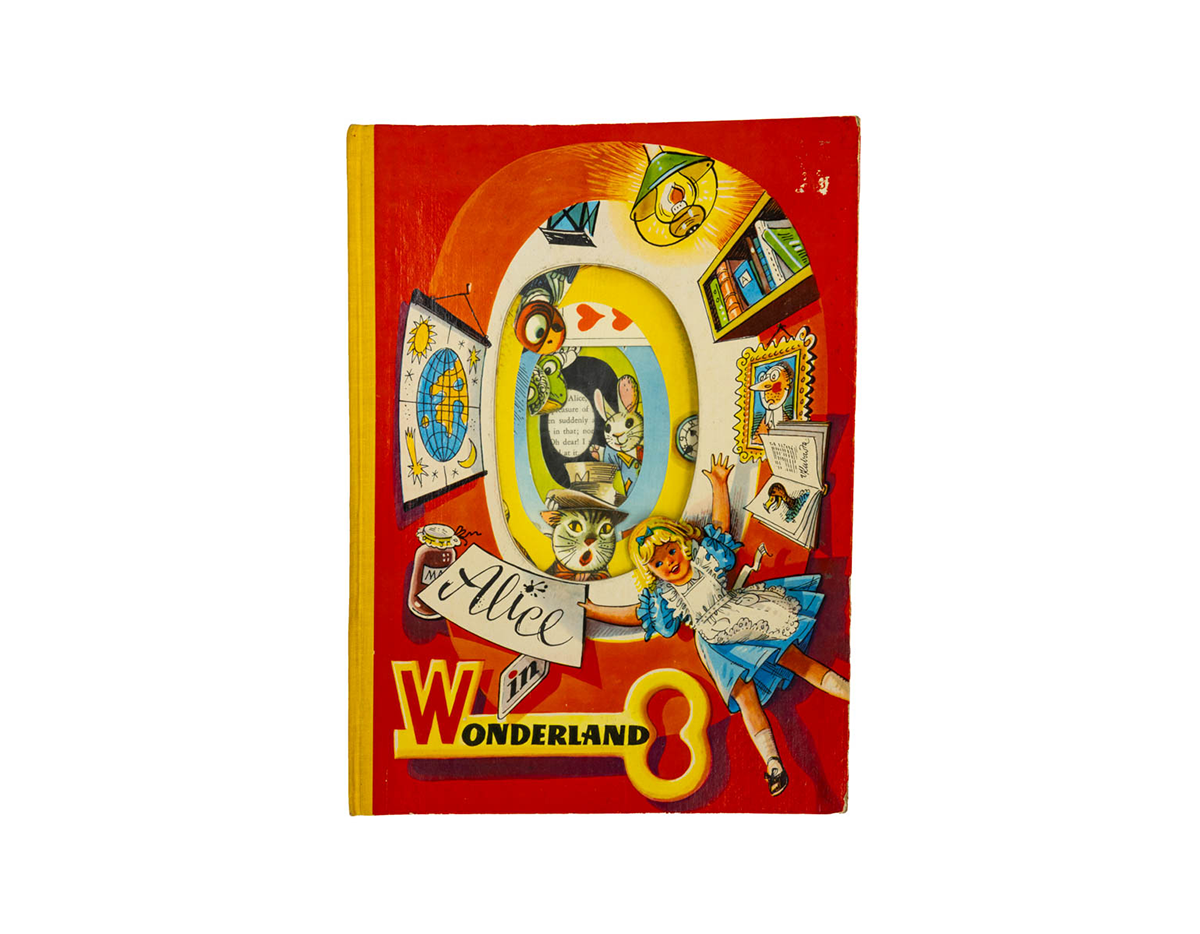

Alice in Wonderland pop-up book by Vojtěch Kubašta, c. 1960.

Vojtěch Kubašta is a name unfamiliar to most Americans. It's not surprising, as Kubašta lived and worked in Prague, behind the Iron Curtain in what is now the Czech Republic, for most of his life. But his name is revered among lovers of pop-up and movable books. He was an innovative storyteller, blending his deceptively simple artistry with imaginative movable and pop-up designs. His quiet ingenuity influenced and impacted others who created three-dimensional books, ushering in a resurgence of pop-ups.

Vojtěch Kubašta (1914-1992) was born in Vienna, Austria, but his family soon moved to Prague in what is now the Czech Republic. At an early age, Kubašta knew he wanted to be an artist. As a boy and young man, he filled pages and pages with drawings, sketches, and illustrations. In the early 1930s, he enrolled in the Czech Polytechnic University in Prague, studying to be an architect—a discipline that allowed him to do something with his hands and later helped him design movable and pop-up books. His university friends remembered Kubašta as an artist who studied architecture.

Kubašta honed his artistry and design skills over the next few decades. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Kubašta designed stage sets for puppet theater -- a growing artistic movement in Czechoslovakia during the interwar years. (This experience, too, influenced his later mastery of movable and pop-up designs.) He taught graphic design. Kubašta also worked for a local plastics company, designing household items and creating marketing and advertising promotions. And as war engulfed Europe and the Czech people were overrun by Germany, Kubašta avoided run-ins with the Nazi occupiers, illustrating literary classics, fairy tales, children's books, and local interest subjects that appealed to national pride.

Kubašta continued his artistic journey after the end of World War II and the communist takeover of then-Czechoslovakia. Prague's printing industry had survived relatively intact, but communist control and censorship severely limited publishing output. Many Czech publishing houses closed. Yet, Kubašta persevered, creating advertisements and promotional materials and illustrating books, maps, posters, and other ephemera for several state-run agencies. He also devised ads with movable elements while working for the Czechoslovakian Chamber of Commerce.

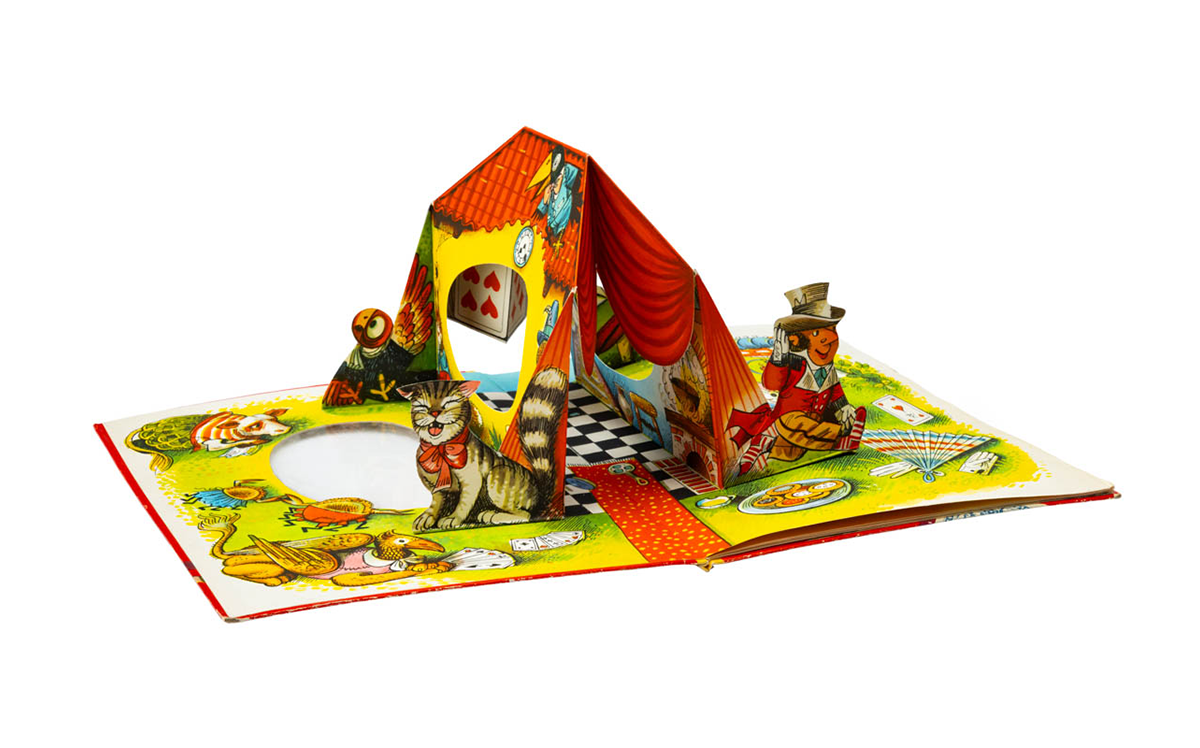

In 1953, Kubašta began working for Artia, the state-run publishing and trading house. He offered his first pop-up book to Artia a few years later. Although he considered this first attempt crude, he would soon master the technique. Kubašta would add movable elements and create visuals to his pop-up books that extended beyond the pages, soaring over the book's flatness. Many of these pop-up books employed a stage-like setting -- pages with text parallel to the spine and that opened to a 90-degree angle to reveal three-dimensional scenery. These books' designs drew on his training as an architect and his work in puppet theater.

However, it wasn't only the three-dimensional elements that made Kubašta's books special. His richly colored illustrations are deceptively simple, filled with wit, humor, and little surprises. Kubašta masterfully blended two- and three-dimensional artistry, creating a visual unity to capture the imaginations of children and adults alike.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Artia contracted with several publishing houses in Western Europe, like Bancroft & Company of Westminster, London, to distribute Kubašta's works. Some of these children's storybooks made it to the United States. Alice in Wonderland, produced around 1960, displays the talent of Kubašta: soaring pop-ups, an innovative front cover (a die-cut opening covered with cellophane representing the rabbit hole), and bright, detailed illustrations with delightful surprises.

The oval die-cut opening on the cover is lined with cellophane, resembling the rabbit hole down which Alice fell. When closed, the images in the first pop-up are skillfully layered, allowing the reader to view some of the characters without opening the book. Kubašta was known for adding unusual materials, such as cellophane and foil, to his books. / THF803657

The oval die-cut opening on the cover is lined with cellophane, resembling the rabbit hole down which Alice fell. When closed, the images in the first pop-up are skillfully layered, allowing the reader to view some of the characters without opening the book. Kubašta was known for adding unusual materials, such as cellophane and foil, to his books. / THF803657

Open the book and discover this colorful pop-up filled with delightful illustrations depicting characters and images from Alice in Wonderland looming over the page. / THF803671

Open the book and discover this colorful pop-up filled with delightful illustrations depicting characters and images from Alice in Wonderland looming over the page. / THF803671

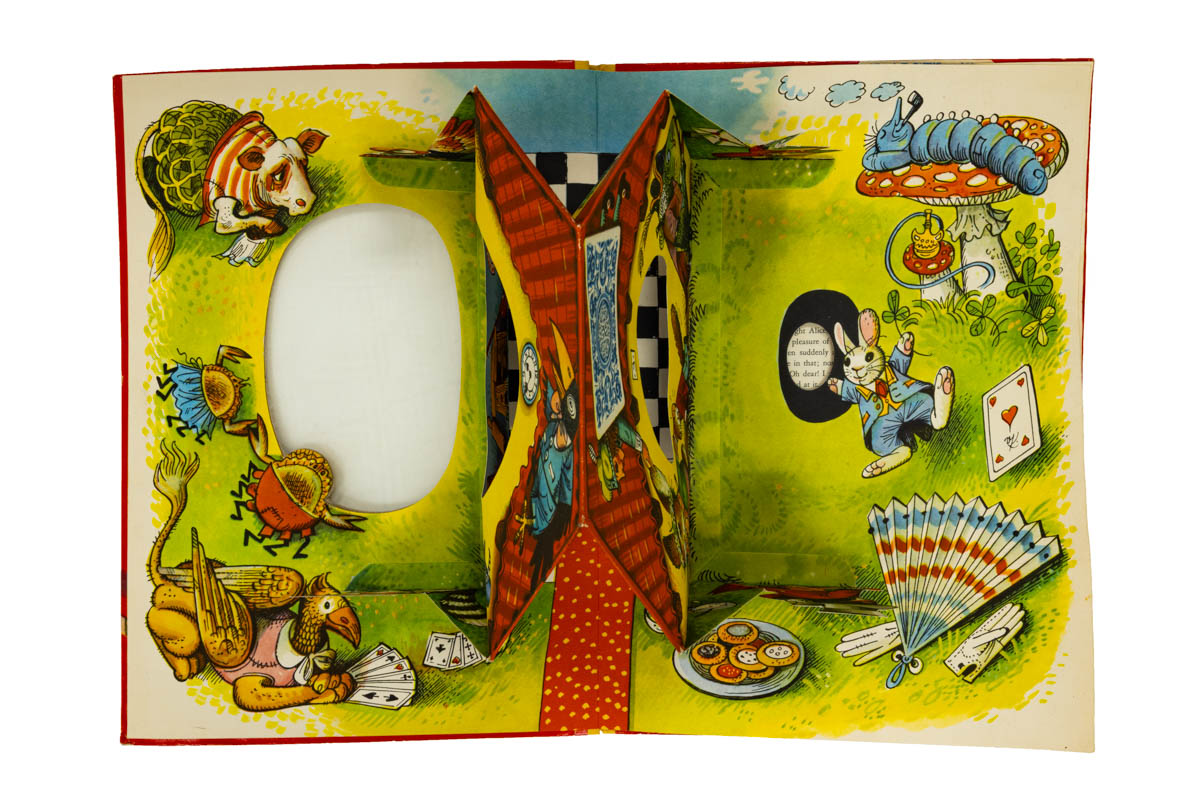

The front pop-up seen from above shows how Kubašta designed the cellophane-covered die-cut to reveal images. Note the large oval on the front cover (left), the oval cutouts in the pop-up house, and the smaller oval on the right (next to the rabbit) showing some of the book's text. / THF803658

The front pop-up seen from above shows how Kubašta designed the cellophane-covered die-cut to reveal images. Note the large oval on the front cover (left), the oval cutouts in the pop-up house, and the smaller oval on the right (next to the rabbit) showing some of the book's text. / THF803658

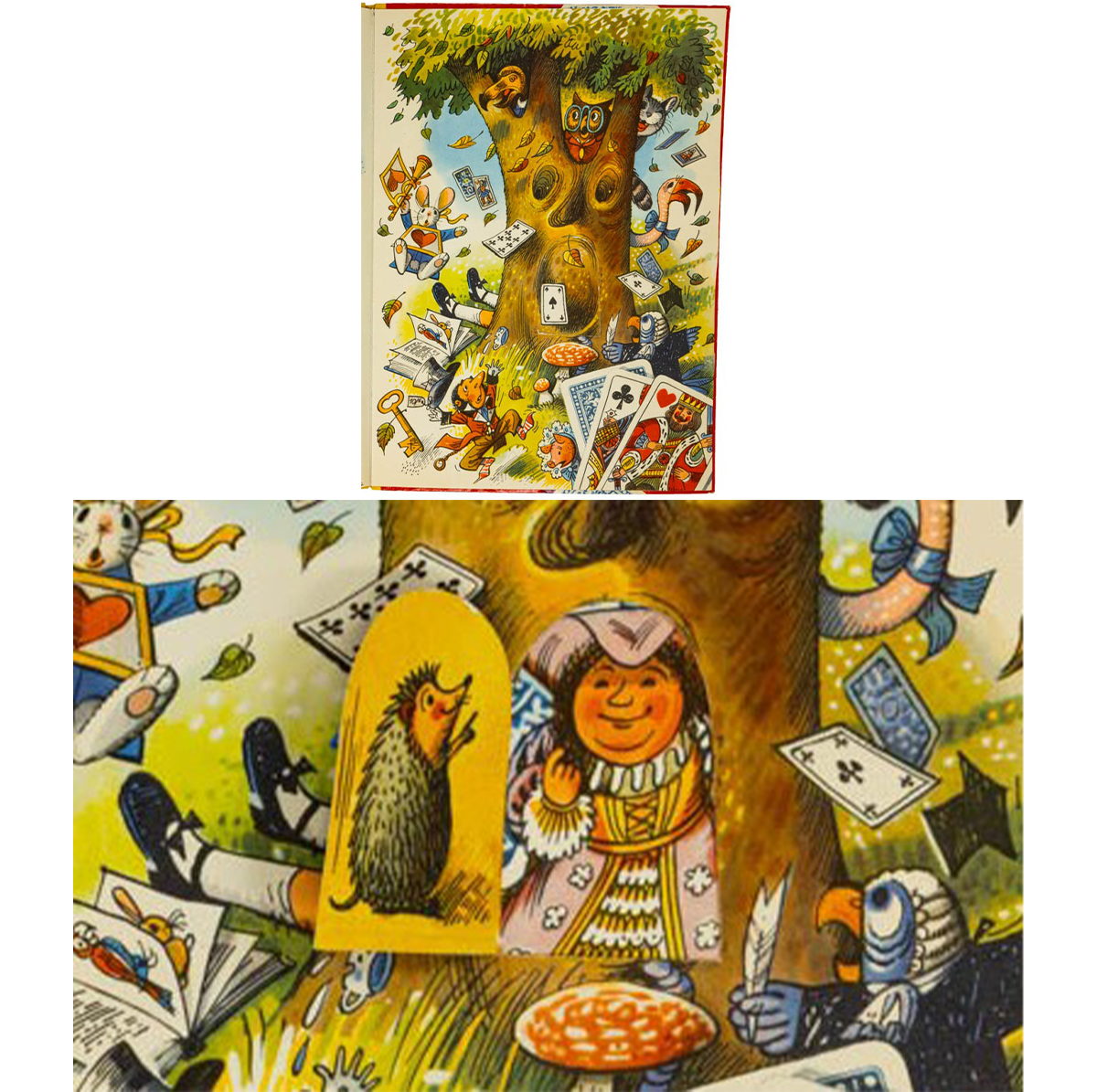

In an illustration at the end of the book, a hidden door in the tree opens to reveal an extra little surprise. / Details of THF803667 and THF803669

In an illustration at the end of the book, a hidden door in the tree opens to reveal an extra little surprise. / Details of THF803667 and THF803669

A host of card characters leap from the page at the end of the book. / THF803679

A host of card characters leap from the page at the end of the book. / THF803679

Kubašta's innovative books and other works that made it to the West caught the attention of entrepreneurs and future movable book artists in America. Waldo Hunt, a self-described "creative businessman," remembers seeing Kubašta's pop-up books in New York in the early 1960s. They inspired him. Hunt's work in advertising and publishing in the early 1960s soon incorporated movable and three-dimensional elements. He created the Wrigley Zoo animal pop-ups for the children's magazine Jack and Jill and, in 1965, published Bennett Cerf's Pop-Up Riddles, a promotional item for Maxwell House coffee. That was just the beginning. Hunt's passion spurred a pop-up book revival in America, jump-starting a new era in three-dimensional publications. He collaborated with Hallmark and Random House, then created Intervisual Communications, a firm that would dominate pop-up publications for decades.

Kubašta's work also influenced artists and paper engineers. When Robert Sabuda was ten, he received a copy of Kubašta's Cinderella. The gift forever changed his view of pop-up books; Sabuda would go on to become an award-winning artist and paper engineer. Other artists, such as Ib Penick and David A. Carter, have also cited Kubašta's influence in their careers

Vojtěch Kubašta's impact was far-reaching. A prolific creator, he produced more than 300 pop-up books during his lifetime and influenced a renaissance in pop-up books. But more than this, his colorful illustrations and imaginative movable and three-dimensional artistry depicted wonder and humor in uncomplicated, simple terms. The universal appeal of his works provides a lasting legacy of innovation that breaks through the confines of borders.

Source and for more information, see:

A. Findlay and Ellen G.K. Rubin. Pop-ups, Illustrated Books, and Graphic Designs of Czech Artist and Paper Engineer, Vojtěch Kubašta (1914-1992). Fort Lauderdale, FL: Bienes Center for the Literary Arts, 2005.

Andy Stupperich is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Thoughtfully Crafted: Sustainable Products from Liberty Craftworks

At The Henry Ford, we have dedicated teams of craftspeople who create beautiful products in our Pottery, Glass, Weaving, and Print shops, which make up Liberty Craftworks in Greenfield Village. While these artisans use traditional techniques, they also do their fair share of innovation. One of the areas in which we have recently expanded is in our offering of products from Liberty Craftworks that use recyclable material sourced on-site.

Bookmarks made from recycled paper. / Image by The Henry Ford

Bookmarks made from recycled paper. / Image by The Henry Ford

Printmakers will check or proof their work by pulling test prints. Most times the results are positive although sometimes the outcome is unexpected. At this point, many prints could be considered misprints that can’t be used. In the Print Shop, they become the perfect opportunity for recycling and creating unique useful items.

Pin-back buttons created from test prints in the Print Shop. / Image by The Henry Ford

Pin-back buttons created from test prints in the Print Shop. / Image by The Henry Ford

For example, the covers of our pocket-size journals were made with test prints from various posters created to be sold in the gift shops. Test print "Makers" posters were trimmed into distinctive bookmarks. A fitting Edison quote was handset and printed on the bookmark finished with a coordinating silver ribbon. Artisans also use test prints to make pin-back buttons. The print is punched with a circle punch and then pressed with a button-maker into coordinating size button hardware ready for a pin back to be added creating a one-of-a-kind button.

Pint glass created from recycled glass. In the background, you can see the variation that occurs, even when using one color of leftover glass. / Image by The Henry Ford

Pint glass created from recycled glass. In the background, you can see the variation that occurs, even when using one color of leftover glass. / Image by The Henry Ford

The Glass Shop uses recycled glass to create rocks and pint glasses. For each "run,'' or production batch, over 200 pounds of glass is diverted from the landfill. As with of our recycled handmade items, the colors of the glassware can vary depending on what colored glass is available and used.

Artisan creating pottery in the Pottery Shop. Mini bowls made from extra clay and remnant glaze are in the foreground. / Image by The Henry Ford

Artisan creating pottery in the Pottery Shop. Mini bowls made from extra clay and remnant glaze are in the foreground. / Image by The Henry Ford

In the Pottery Shop, mini bowls are made from scraps of clay that are mixed together into a recycled clay blend. They are made from a variety of clay colors that are swirled together in the mixing process. Once the pieces are formed, they’re fired in a kiln to 1,950 °F and then dipped into a glaze. The glazes themselves are mixtures of leftover glazes from various projects. The glazed pieces are then fired again, this time to 2,100 °F. Each finished product is unique, and the fact that they are made from clay and glazes that have been recycled only adds to their beauty and distinctiveness.

Pouches made from Weaving Shop remnants, Clothing Studio scraps, and Pottery Shop buttons. / Image by The Henry Ford

Pouches made from Weaving Shop remnants, Clothing Studio scraps, and Pottery Shop buttons. / Image by The Henry Ford

When the Weaving Shop is lucky enough to have remnants, weavers use them to make colorful pouches. These unique creations also provide the opportunity for cross-collaboration among several teams. The pouch linings are made from remnants from the Clothing Studio, our internal textile department that creates all our historically accurate clothing and programmatic costumes. The buttons are scraps from the Pottery Shop. While the pouches are not always available, when they are, no two pouches are exactly alike.

These sustainable pieces help tell the story not only of historical craft, but of the importance of sustainability. The next time you are in one of our stores or shopping online, keep an eye out for these unique creations, and others from our innovative artisans.

- Mendy Grenz, Weaving Shop Lead

- Chris Hoffman, Glass Shop Lead

- Melinda Mercer, Pottery Shop Lead

- Kathy Torres, Print Shop Lead

Compiled by Zachary Ciborowski-Scarsella, Manager of Retail Marketing & Licensing, and Rachel Yerke-Osgood, Associate Curator

Making the Connection: Phoning on the Go

When telephones were first introduced in the late 1800s, people wanting a phone would subscribe to the local phone company’s services and receive a telephone on lease. Using the telephone at this time meant that both caller and receiver were tethered to their respective locations. But as American life became more bustling and more people found themselves away from home for greater portions of their day, telephone technology adapted.

Pay telephone featuring patents by William Gray, circa 1898 / THF805358

Pay telephone featuring patents by William Gray, circa 1898 / THF805358

In 1889, the first public, coin-operated pay telephone was installed in Hartford, Connecticut, at the Hartford Connecticut Trust Company. The device had been conceived of and patented by William Gray; according to legend, he was inspired by his inability to find a publicly available phone when his wife was ill and needed a doctor. The pay telephone worked by creating slots for different denominations of coins, and different chimes or bells would sound as the money was deposited. Once the right amount had been deposited—the operator could tell by the chimes—the call would be put through. The Gray Telephone Pay Station Company, founded by Gray in 1891, would go on to install pay telephones across the country and refine their designs, creating different models for different needs and locations, from city streets to hotel lobbies. The company would be incredibly successful, even surviving the Great Depression before being bought out by Automatic Electric in 1948.

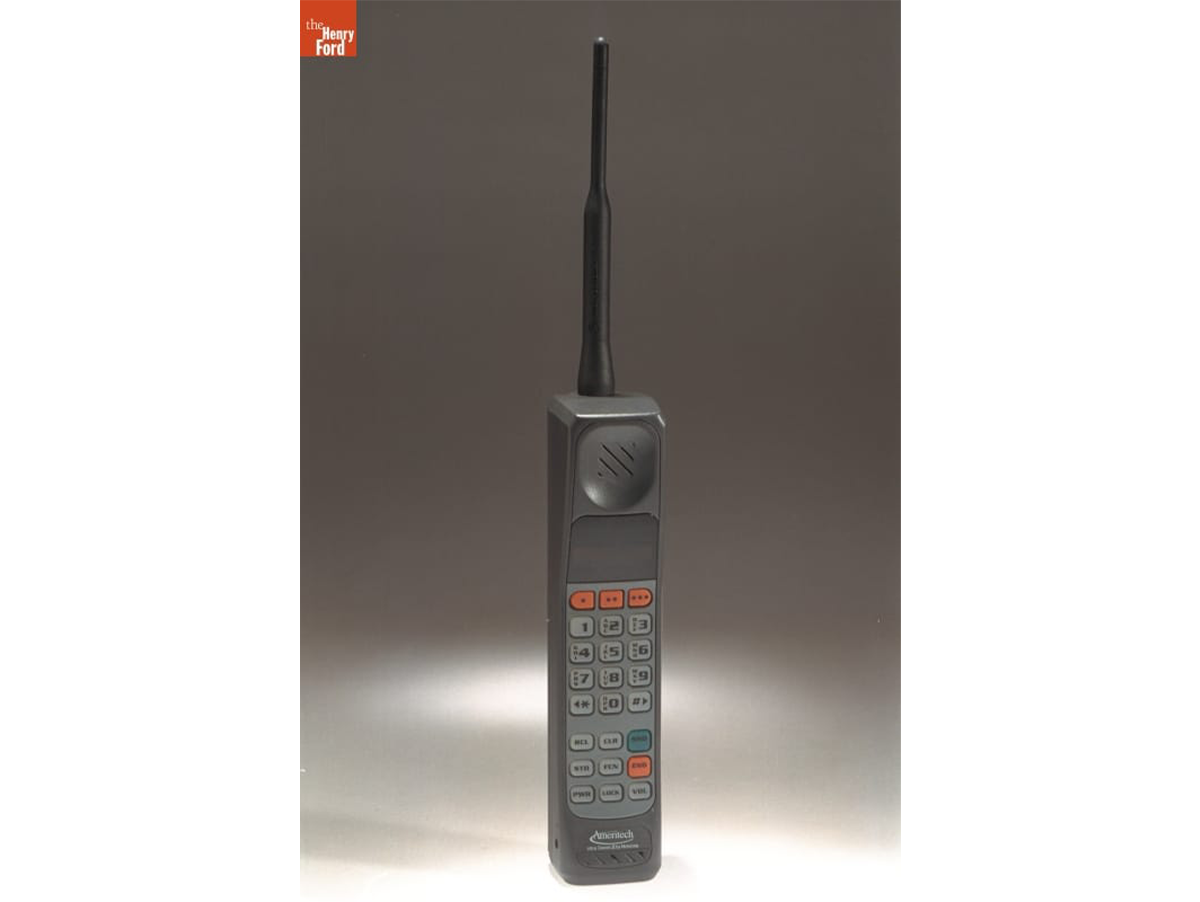

Motorola Brick Phone, 1985 / THF97588

Motorola Brick Phone, 1985 / THF97588

On April 3, 1973, Motorola engineer Martin Cooper made the first publicized cell phone call—to Joel Engel, who was working at AT&T trying to develop the same technology, which would allow users to make calls without having a physical connection to a network, unlike previous phones. While the car phone—a device that was mounted in the trunk of a car, with cables running through the vehicle to connect to a headset in the cabin—already existed and allowed for some mobile communication, its adoption was intentionally limited by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which required licenses for its use. Motorola continued refining their cellphone technology, and in 1983 they had the first commercially available cellphone ready for the market. By 1990, over one million Americans were using cellphones.

Pay phones and mobile phones help people get in touch on the go. But what about when the recipient, not necessarily the caller, is out and about? For that, we turned to different technologies—including the answering machine and the pager.

AT&T Model 2100 Telephone Answering Machine, circa 1983 / THF323526

AT&T Model 2100 Telephone Answering Machine, circa 1983 / THF323526

Although the first automatic answering machine was invented in 1935, the first commercially viable machine didn’t arrive until 1971, with PhoneMate’s Model 400. By the end of the 1980s, one in three American households owned an answering machine. While the concept may seem simple, the implications for telephone culture were immense. Now there was a way to be continuously available; even if you were away from your telephone, the machine would make sure that the caller’s message was there waiting for you when you returned. The adoption of answering machines also led to a change in the culture around phone calls. On the one hand, calls were easier to screen, but on the other, a missed call no longer meant the onus was on the caller to try again, but rather on the recipient to phone back.

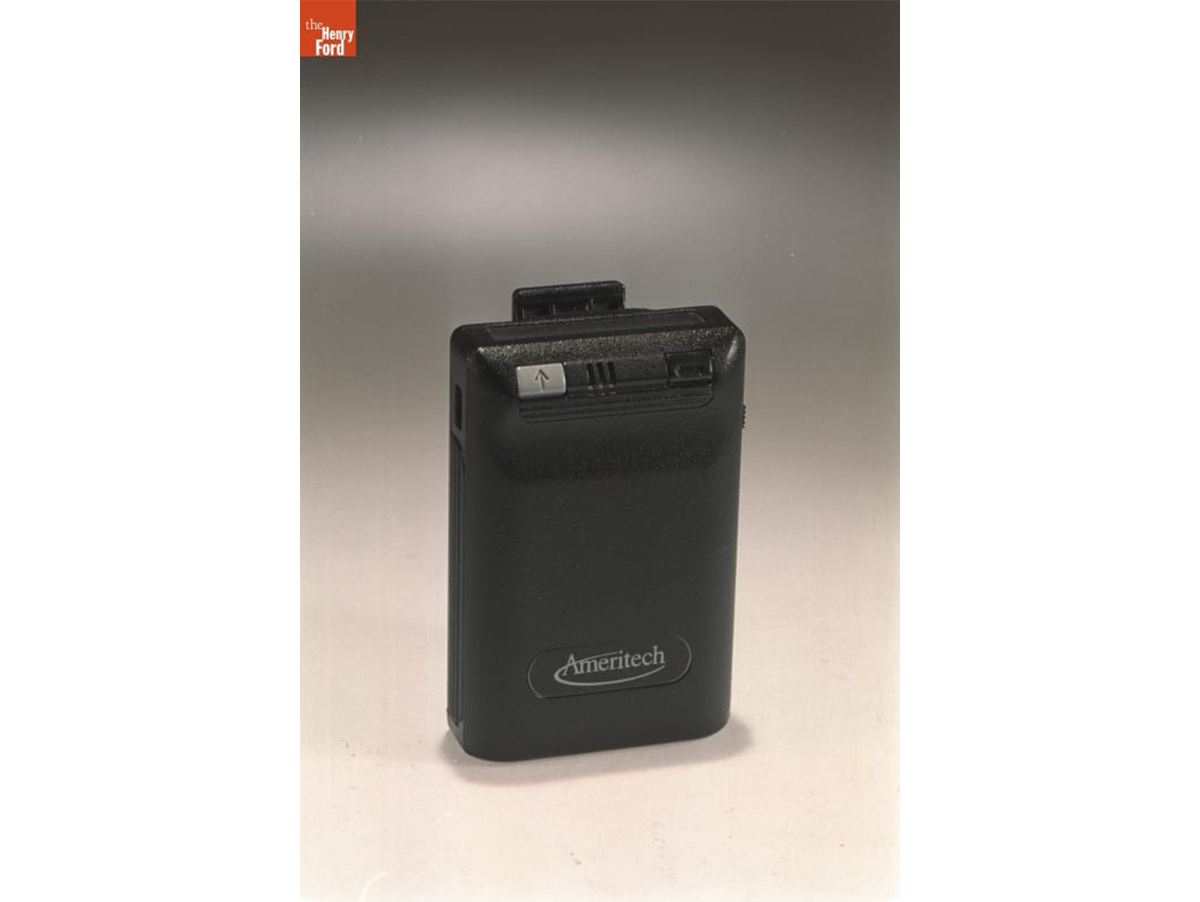

Motorola Pager, 1995 / THF302299

Motorola Pager, 1995 / THF302299

In 1949, wireless communication pioneer Al Gross patented the very first telephone paging device. The following year, the device was put into service at New York's Jewish Hospital—marking the start of what would be a long history of use in critical communications. In 1959, Motorola coined the term “pager,” and the name stuck; in 1964, they would become the main force in the pager market with the first versions available to consumers. While the first pagers delivered tone-only messages, by the 1980s new versions had been developed that displayed alpha-numeric messages, allowing people to send short messages without having to pick up a phone. By 1994, over 61 million pagers were in use. Although the rise of cell phones with the ability to send text messages led to pagers falling out of favor with the general public, pagers remain a crucial part of many hospitals' and first responders' communication systems.

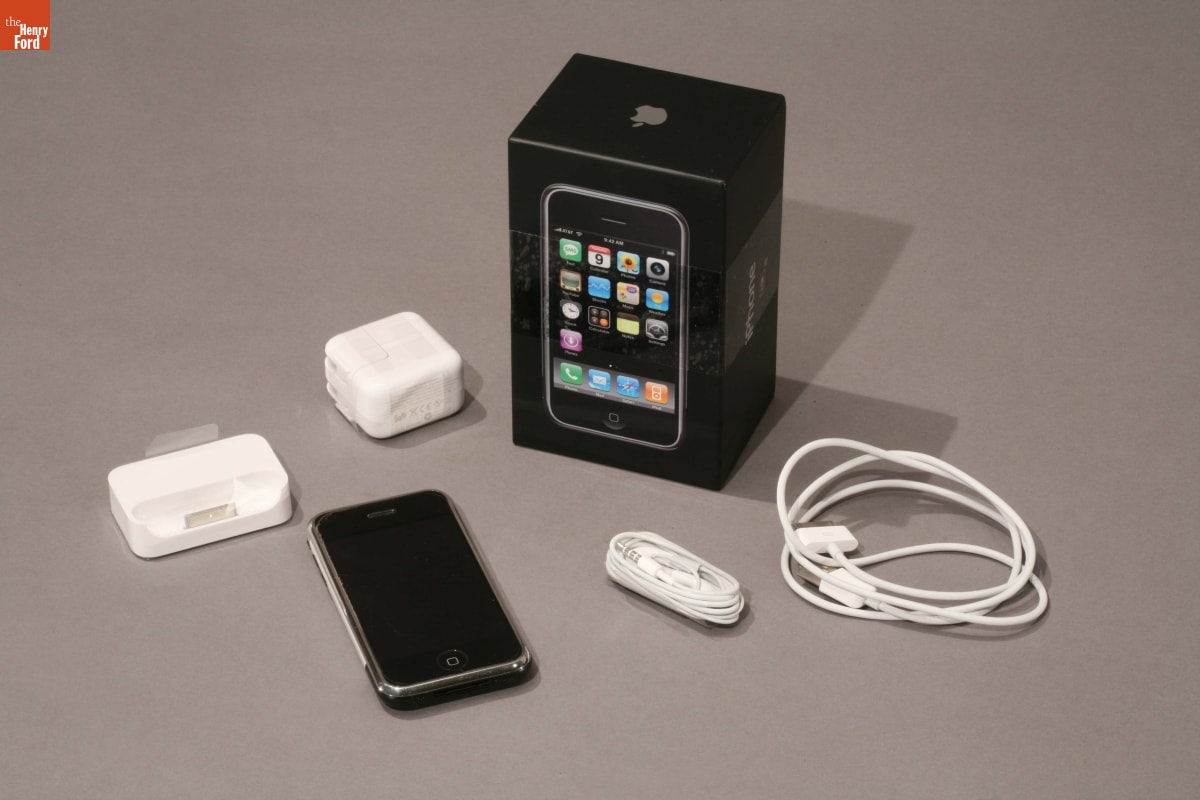

iPhone, 2007 / THF92290

iPhone, 2007 / THF92290

Of course, thanks to the smartphone, our telephone technology now solves more problems than ever before, all in a conveniently portable package. Landline telephones have waned in popularity, and for many of us, our mobile phone is now our only phone. We can text paragraphs of thoughts with a few swipes on a screen. Our phones not only automatically come with a voicemail function, but many of them will even transcribe the messages for us. We’re more reachable than ever before, yet many of us talk on the phone even less. The remnants of the technology that led to this moment still exist, though—just waiting for us to make the connection.

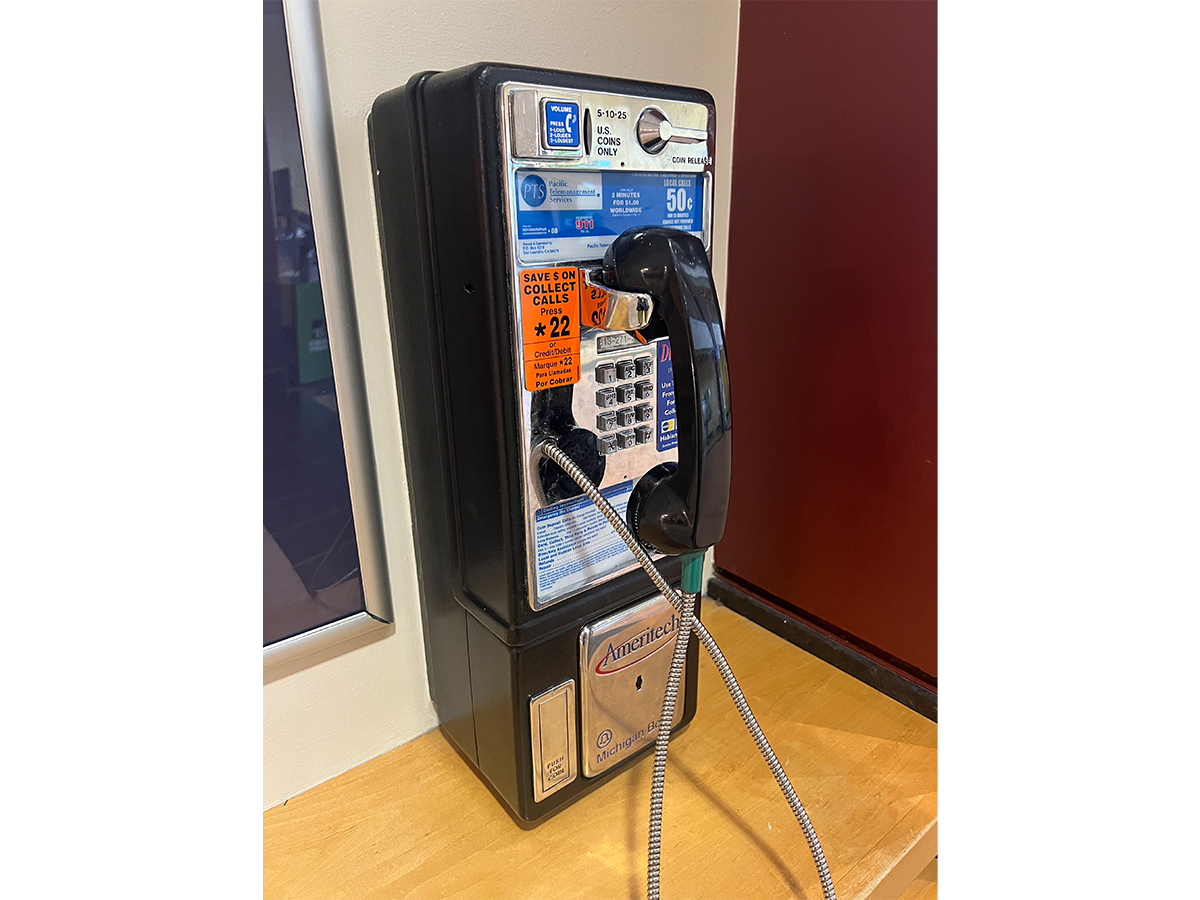

A functioning pay phone can still be found—and used!—in the Welcome Center at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by Rachel Yerke-Osgood

A functioning pay phone can still be found—and used!—in the Welcome Center at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by Rachel Yerke-Osgood

The Henry Ford's 1898 pay telephone was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Servcies (IMLS).

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The Jackson Home—Unpacking a Family's Story

In the spring of 2023, the contents of an entire house—9,000 everyday objects, including photographs, documents, books, and household items—were logged, packed, and shipped from Selma, Alabama to Dearborn, Michigan. That house was the Jackson Family Home, which was recently moved to its new permanent home in Greenfield Village—you can find out more about the move here. The items arrived and staff started their work to introduce them into The Henry Ford's Collection.

Contents of the Jackson Family Home are packed in boxes and await loading for shipment from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Contents of the Jackson Family Home are packed in boxes and await loading for shipment from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Following the arrival of these materials to Michigan, two-dimensional materials were separated and inventoried as part of The Henry Ford’s Archives and Library collection, located in the Benson Ford Research Center. These materials were then sent to an abatement contractor and gamma irradiated to best preserve them for posterity. This interventive treatment sterilizes and decontaminates potential hazards, without causing any harm to the object. With the materials returned on-site, a processing archivist completed an intensive inventory, intellectually arranging, drafting descriptions, and rehousing the materials to increase accessibility and prepare them for use by researchers and the public.

Staff at The Henry Ford organize archive and library materials in preparation for work with an abatement contractor. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Staff at The Henry Ford organize archive and library materials in preparation for work with an abatement contractor. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Many of these materials are being used to fuel the interpretation and visualization of the Jackson Home for its opening in the summer of 2026.

Photograph of Jawana Jackson in the Jackson Family Home. / THF708595

Photograph of Jawana Jackson in the Jackson Family Home. / THF708595

Processing of the three-dimensional artifacts began with unpacking 100 items at a time and assigning a temporary inventory number to each object. This number allows us to track the items as they move through various stages of processing. After inventory, high-resolution reference photographs are captured. This data is uploaded to our digital cataloging system and the items are then transferred to the conservation lab. In April 2023 this phase was completed, but there are several ongoing processing phases that will continue through 2026.

Carts are used to assist in relocating artifacts between stages of processing for the Jackson Home Project. A. L. Hirsch Rover Pottery Dachshund Ceramic Dresser Caddy and United China and Glass Company Pink and White Berries and Bird Leaf bowl are shown being relocated on a cart. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Carts are used to assist in relocating artifacts between stages of processing for the Jackson Home Project. A. L. Hirsch Rover Pottery Dachshund Ceramic Dresser Caddy and United China and Glass Company Pink and White Berries and Bird Leaf bowl are shown being relocated on a cart. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Every artifact from the Jackson Family Home undergoes multiple rounds of cleaning and repair in conservation. The process began when the contents of the home were packed in Selma—where larger items were lightly vacuumed to remove dust. Once on-site at The Henry Ford, each item was thoroughly cleaned and vacuumed during unpacking, providing the first opportunity to check the condition of objects for missing parts or signs of deterioration. Once in the conservation lab, a condition report and treatment plan are created for each object.

Associate Conservator Kate Herron adds netting to the arms of this Floral Globe Furniture Company armchair, an object used in the Jackson Family Home, for extra stability. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Associate Conservator Kate Herron adds netting to the arms of this Floral Globe Furniture Company armchair, an object used in the Jackson Family Home, for extra stability. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Treatment options can range from light cleaning to restoration or more extensive repairs, depending on the artifact’s condition. Regular meetings with curators at The Henry Ford help determine the appropriate level of cleaning, which items need preservation to address wear or evidence of use, and how each object contributes to the overall narrative.

Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable consults with Conservator Louise Beck on conservation treatment of conservation treatment of a Cosco High chair with steps used in the Jackson Family Home kitchen. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable consults with Conservator Louise Beck on conservation treatment of conservation treatment of a Cosco High chair with steps used in the Jackson Family Home kitchen. / Photograph by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Simple treatments, like wiping down with deionized water or ethanol, are often sufficient for stable items with light dirt. For kitchen equipment, layers of grease and dust are removed. Some artifacts require more complex treatments, including the repair of broken pieces or removal of corrosion from metals. To prevent deterioration, protective coatings like lacquer are used for brass and silver objects, and specific chemical treatments for iron and steel. Once treatment is complete, the object's condition and treatment details are documented in the catalog record, and the objects continue their journey to The Henry Ford’s registrar staff.

Yellow Cosco Highchair with steps used in the Jackson Family Home, after conservation treatment. / THF803856

Yellow Cosco Highchair with steps used in the Jackson Family Home, after conservation treatment. / THF803856

The registrar is responsible for research and cataloging each artifact. They build individual catalog records for each object with data such as size, maker, date of creation, and the purpose of the object. Every item is assigned a unique identifier, or an "accession number," that connects that object with a specific record. Accession numbers provide detailed information about the year the object was received into The Henry Ford’s collection, the collection “lot” it is a part of, and the specific registration succession number it is assigned. This unique identification number is attached or physically written on the artifact to ensure it can be traced to its record. Artifacts are labeled in a method that may be removed, if desired or needed down the road, without damage to the object. In addition to the photographic documentation in the collection, this research aids our understanding of what time period(s) the object lived in the Jackson Family Home.

Artifacts in The Henry Ford collection are physically labeled with their accession number. A school bell from the Jackson Family Home is shown being labeled by Collections Specialist-Cataloger Andrew Schneider. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Artifacts in The Henry Ford collection are physically labeled with their accession number. A school bell from the Jackson Family Home is shown being labeled by Collections Specialist-Cataloger Andrew Schneider. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

The artifact then proceeds to photography for a high-resolution image. In 2026 the digitized objects and images from the Jackson Family Home will become accessible to the public on The Henry Ford’s digital collection, which can be accessed on The Henry Ford's Digital Collections website.

The Henry Ford Photographer Jillian Ferraiuolo, capturing a photograph of a Breakfront China Cabinet from The Jackson Family Home. Digitizing our collection allows artifacts to be accessible, even when not on exhibition. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford Photographer Jillian Ferraiuolo, capturing a photograph of a Breakfront China Cabinet from The Jackson Family Home. Digitizing our collection allows artifacts to be accessible, even when not on exhibition. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Breakfront China Cabinet. / THF803854

Breakfront China Cabinet. / THF803854

Once processing has concluded, the object is prepared for its new home in the collection, whether that is preparing for handoff to the exhibition team for installation in the Jackson Family Home, used in temporary exhibitions, or moved to storage for future research and opportunities.

This blog was produced by multiple authors: Kristen Hollingsworth, Jackson Home Project Coordinator; Louise Beck, Conservator, Julia DiLaura, Collections Specialist; Ashley Wimbrough, Collections Specialist; Andrew Schneider, Collections Specialist Cataloger; Jack Schmitt, Processing Archivist; and Aidan Thomas, Conservation Specialist at The Henry Ford.

by Kristen Hollingsworth, by Louise Stewart Beck, by Julia DiLaura, by Ashley Wimbrough, by Andrew Schneider, by Jack Schmitt, by Aidan Thomas

The Oldest Cars Shine at 2025 Old Car Festival

Its top down under bright skies, this Ford Model A kept pace with the Torch Lake locomotive at the 2025 Old Car Festival. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pleasant temperatures and sunny skies greeted visitors and participants alike at our 2025 Old Car Festival, held in Greenfield Village on September 6 and 7. More than 750 vintage cars, trucks, motorcycles, and bicycles registered for this year’s event, making for one of the largest festivals in recent years. Throughout the weekend, the village was filled with the sights and sounds of early gasoline, steam, and electric cars all dating no later than 1932.

We choose a special theme for each year’s show. Often it’s a specific make or model, and sometimes it’s a geographic location or style of automobile. This year we went big by celebrating an entire century with our focus on Nineteenth-Century Motoring. The automobile may have defined the twentieth century, but its origins and earliest impacts lie firmly in the 1800s, from Karl Benz’s pioneering Patent-Motorwagen of 1885 to the Duryea brothers’ first series-produced automobile in 1896.

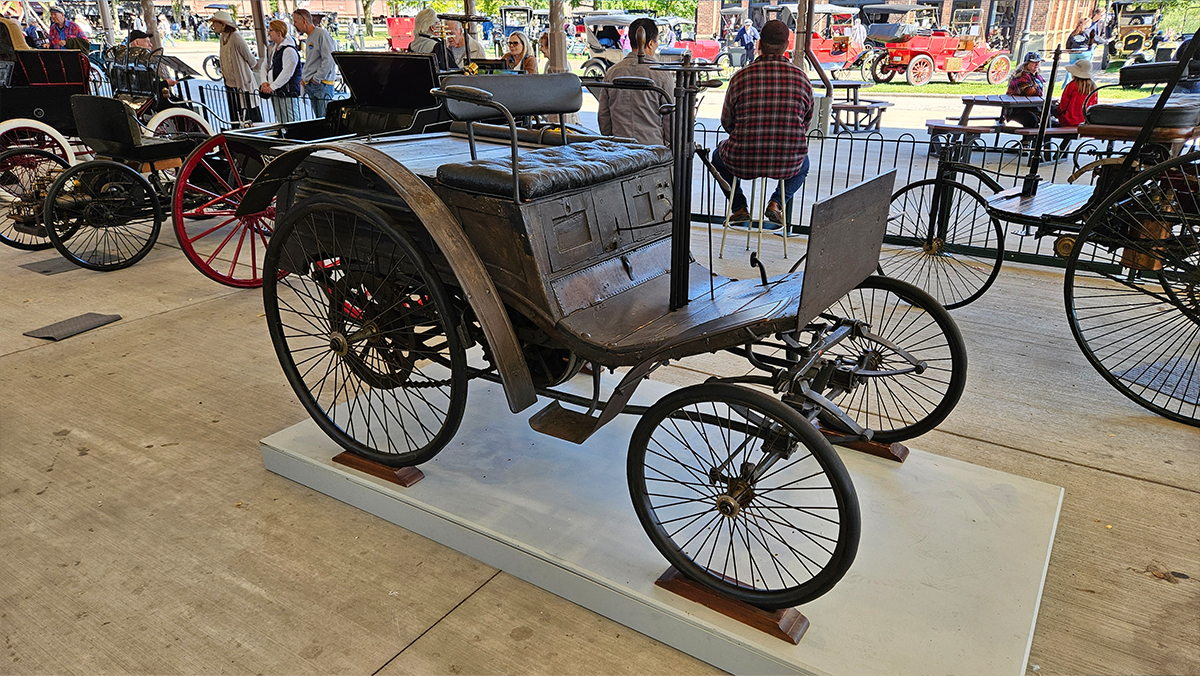

The Henry Ford’s 1893 Benz Velocipede, one of eleven pre-1900 vehicles shown in Detroit Central Market, embodied the festival’s Nineteenth-Century Motoring theme. / Image by Matt Anderson

Incredibly, Old Car Festival featured eleven pre-1900 vehicles in Detroit Central Market. Four of them came from The Henry Ford’s own collection including an 1893 Benz Velocipede, our replica of Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle, an 1898 Autocar Runabout, and, perhaps most interesting of all, a conjectural full-size model of George Selden’s Motor Buggy based on his notorious patent first applied for in 1879 and awarded in 1895. Participants added another five vehicles to the mix, including a replica of an Iowa-built 1890 Morrison Electric, an 1896 Riker Electric prototype, an 1897 De Dion-Bouton Tricycle, an 1898 Beeston Quadricycle, and an 1899 Marot-Gardon. Our neighbors at the Automotive Hall of Fame provided two additional vehicles: replicas of the Benz Patent-Motorwagen and Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach’s 1885 Reitwagen motorcycle.

Visitors were treated to a variety of experiences throughout the village. Not far from the entrance, at the Ford Home, the Early Engine Club staged a Farm Power Expo showcasing early tractors and stationary engines, including The Henry Ford’s Pullford farm tractor — created from a Ford Model T using a widely marketed conversion kit. Outside the nearby Bagley Avenue Workshop, presenters demonstrated a replica of Henry Ford’s 1893 Kitchen Sink Engine that represented his first steps in the nascent automotive industry.

Old Car Festival included a number of imports like this 1924 Jowett made in Great Britain. / Photo by Matt Anderson

As is the custom at Old Car Festival, participating vehicles were parked in chronological order throughout Greenfield Village. The earliest automobiles sat near the Armington & Sims Machine Shop near the village entrance, while late 1920s and early 1930s cars had space near the Daggett Farmhouse. The Village Green was reserved for judged cars. Vehicle class awards were given based on authenticity, quality of restoration work and the care with which each car was maintained. First-, second- and third-place prizes were awarded in eight classes, and one overall Grand Champion was selected for the festival. We also presented two Curator’s Choice Awards to two unrestored vehicles. The complete list of our 2025 Old Car Festival award winners is available here.

Bicycles had their own pass-in-review sessions, ably narrated by Bill Smith, on Saturday and Sunday mornings. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Old Car Festival visitors were welcome to explore the village and learn about the cars on their own. As always, participants were eager to share stories and insights about their vehicles. But visitors interested in a more formal presentation could attend pass-in-review sessions throughout the weekend. Vintage vehicles were driven past a set of bleachers on Main Street where expert historians offered commentary on each one. Sometimes the narration included dates and production figures for a vehicle’s manufacturer, and other times it was a broader statement on that car’s impact on technology or design. These narrated sessions also provided an opportunity for us to individually thank our participants by giving them a moment in the spotlight.

Martha-Mary Chapel hosted its own series of special presentations. Automotive historian Andy Dervan shared a look at Ford Motor Company’s monthly publication, Ford Times, which launched in April 1908. Always promotional but often informative, Ford Times included travelogues, customer testimonials and general news on the company and its products. Roadside historian Daniel Hershberger shared insights on automobile touring and camping in the first decades of the 20th century. Not far from the chapel, next to Scotch Settlement School, Hershberger staged an impressive display of vintage camping equipment. Meanwhile, presenter Ray Swetman offered an informative talk in the chapel about Henry Ford’s efforts to finance Ford Motor Company, his third attempt at auto production, in 1903.

The Georgia farmhouse of Amos and Grace Mattox represented the trying Depression years, accented by a well-worn Ford Model TT parked out front. / Image by Matt Anderson

Music featured prominently in this year’s show. Old Car Festival’s 40-year timespan allowed for a variety of musical styles. The corner of Washington Boulevard and Post Road hosted a ragtime street fair, complete with a cakewalk set to syncopated piano rags by Scott Joplin and other giants of the genre. The River Raisin Ragtime Review orchestra joined the festivities on Saturday evening with a concert on Main Street. Throughout the weekend at the Mattox Family Home, Rosa Warner-Jones performed a selection of poignant gospel and blues songs evocative of the Georgia lowlands during the Great Depression. The Village Trio vocal group, the Greenfield Village Quartet and other artists added to the experience.

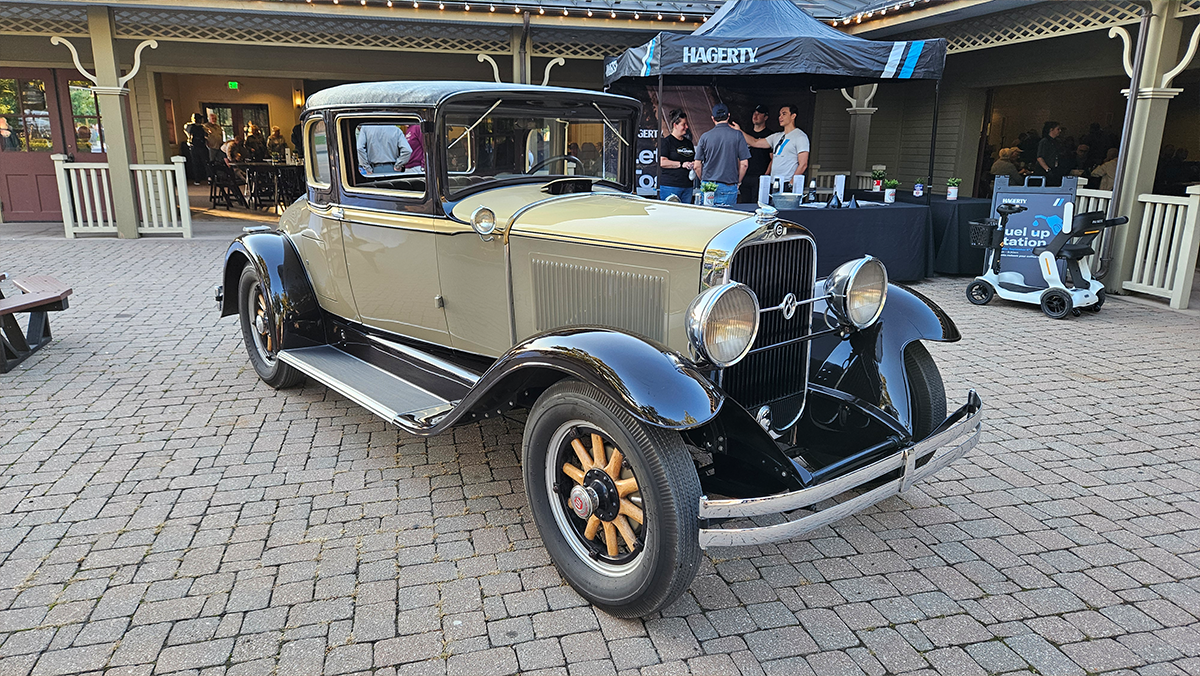

Hagerty’s 1930 Studebaker Victoria coupe drew onlookers at the Lodge. / Image by Matt Anderson

Once again, our friends at Hagerty helped make Old Car Festival the success it was. Not only did they sponsor their terrific youth judging program, in which children 8-10 years old get to view and choose their favorite cars; Hagerty also brought a 1930 Studebaker Commander 8 that fit in perfectly at the show. Hagerty had an active presence near the Herschell-Spillman Carousel with magazines, newsletters and fun promo products available to all comers.

We extend a special thanks to all the participants, presenters, performers and guests who made the 2025 Old Car Festival so special. This one may be in the history books, but you can be sure that we’re already looking forward to next year.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

The Many Journeys of The House by the Side of the Road

Dr. Sullivan Jackson on the front steps of The Jackson Home, circa 1999. The house reflects changes made in the late 1960s and 1970s. / Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group / Photo by Ed Jones, Birmingham News.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson on the front steps of The Jackson Home, circa 1999. The house reflects changes made in the late 1960s and 1970s. / Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group / Photo by Ed Jones, Birmingham News.

In 2026, The Jackson Home from Selma, Alabama, will open in Greenfield Village, becoming the first home to be added to this collection of historic structures in over 40 years. The home comes to us with the inspiring story of a courageous family and community at the forefront of one of the most crucial moments in the Civil Rights Movement in America. Their tireless efforts, spotlighted on national and world stages, would eventually lead to the signing of the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965.

During the first months of 1965, the home of Dr. Sullivan and Mrs. Richie Jean Jackson and their young daughter, Jawana, served as a key backdrop to the world-changing events in Selma. Their modest yet well-appointed home provided a safe haven for Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists planning the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, and acted as a communication hub, including ongoing calls to and from the White House.

It’s fitting that this home joins buildings associated with other extraordinary Americans, such as Abraham Lincoln, George Washington Carver, Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford, who also achieved remarkable things. It’s also fitting that The Jackson Home is not a grand mansion. Instead, the home is an Arts & Crafts single-story southern bungalow, a style that became prevalent in neighborhoods across the country in the early 20th century. While Greenfield Village has a few 20th-century buildings, none are of this Arts & Crafts style.

The home will be restored to its 1965 appearance, both inside and out, reflecting the changes made by three generations of African American dentists who lived there between 1919 and 1965.

The home of Dr. R.B. Hudson, next door to The Jackson Home. Designed by Wallace A. Rayfield in 1910

The home of Dr. R.B. Hudson, next door to The Jackson Home. Designed by Wallace A. Rayfield in 1910

The Jackson Home was commissioned by Dr. Richard Hudson as a wedding gift for his daughter, Leola Hudson, in 1919. Dr. Hudson was a prominent Alabama businessman and an important figure in Alabama’s black educational community. He was closely associated with Dr. Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute (now University), and was a benefactor of Selma University, which stood just down the street from his home. Hudson’s own home was designed by Wallace A. Rayfield in 1910, so it is not surprising that the new home for his daughter and her new husband, Dr. William Whitted, would also be a Rayfield design.

Wallace A. Augustus Rayfield and students in a mechanical drawing class at the Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama, circa 1902. / Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston, courtesy of Library of Congress

Wallace A. Augustus Rayfield and students in a mechanical drawing class at the Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama, circa 1902. / Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston, courtesy of Library of Congress

Wallace A. Rayfield provided designs for the remodeling of the home of Dr. L.L. Burwell in 1910. The Burwells are related to The Jacksons and this home stood just around the corner from The Jackson Home. / THF725295

Wallace A. Rayfield provided designs for the remodeling of the home of Dr. L.L. Burwell in 1910. The Burwells are related to The Jacksons and this home stood just around the corner from The Jackson Home. / THF725295

The connection to Wallace A. Rayfield emerged early in our Jackson Home research. At the time the house was built, Rayfield was one of only two formally trained African American architects in America. After earning degrees from Howard University, Columbia, and the Pratt Polytechnic Institute, he began his career teaching architectural design and technical drawing at Tuskegee Institute. In 1908, Rayfield opened his own firm in Birmingham, Alabama, where he built a thriving business designing homes, schools, churches, and other public buildings for the growing black middle class. In 1909, Rayfield designed the famous 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the site of the horrific bombing that killed four young girls in 1963.

16th Street Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama, designed by Wallace A. Rayfield in 1909. / THF725347

16th Street Baptist Church, Birmingham, Alabama, designed by Wallace A. Rayfield in 1909. / THF725347

Floor plan of The Jackson Home highlighting each of the additions. / From the Historic Structures Report prepared by Quinn Evans.

Floor plan of The Jackson Home highlighting each of the additions. / From the Historic Structures Report prepared by Quinn Evans.

Dr. William and Leola Whitted lived in the home from their marriage in 1919 until Dr. Whitted’s death in 1940. In its first iteration, the house was sided in narrow painted clapboard with a wooden shingled roof. It ended at the kitchen door, with another doorway leading out from the hallway onto a covered porch. The house was heated by individual fireplaces with coal grates, with a coal stove likely in the kitchen, and featured indoor plumbing and electricity. Remarkably, all the original 1919 windows survived and will be reinstalled in the house.

In the late 1930s, as Dr. Whitted's health declined, Dr. Eric Portlock, a cousin of Leola's, joined the dental practice. After Dr. Whitted's death in 1940, Dr. Portlock took over the practice, and he and his wife, Bennie, moved into the house as tenants, while Leola relocated to Montgomery.

Under Bennie Portlock's care, the home became a center of hospitality for many of the women's groups, church organizations, and Selma University functions in which she was involved. Her love for gardening, flowers, and color became evident as she put her own stamp on the decor of the house.

Birthday party for Rose Marie Foster (seated) hosted by Mrs. Bennie Portlock (directly behind Rose). This circa 1953 image shows the original features of the dining room and some of Mrs. Portlock's floral wallpaper. Marie Foster, one of Selma's “Courageous Eight,” stands next to her daughter, Rose. Marie was the sister of Sullivan Jackson and worked as a dental hygenist for both Dr. Portlock and Dr. Jackson. / THF708432

Birthday party for Rose Marie Foster (seated) hosted by Mrs. Bennie Portlock (directly behind Rose). This circa 1953 image shows the original features of the dining room and some of Mrs. Portlock's floral wallpaper. Marie Foster, one of Selma's “Courageous Eight,” stands next to her daughter, Rose. Marie was the sister of Sullivan Jackson and worked as a dental hygenist for both Dr. Portlock and Dr. Jackson. / THF708432

In the early 1950s, the Portlocks made significant upgrades to the house, including a large rear addition with a full bathroom, den, and bedroom. Along with these changes, they extensively decorated with colorful wallpapers. The kitchen was partially remodeled and updated, but the original 1919 kitchen cabinets remained in place.

The kitchen of The Jackson Home in 1959. / THF708492

The kitchen of The Jackson Home in 1959. / THF708492

The kitchen of The Jackson Home in 1959. / THF708428

The kitchen of The Jackson Home in 1959. / THF708428

Around this same time, the Portlocks also resided the house in a wide cement board (a maintenance-free upgrade to the painted wooden siding) finished in a fashionable salmon color with white trim, and added a metal shingle roof over the original wooden shakes. These exterior changes remained in place through 1965 and will be restored.

Dr. Portlock died in 1955. Bennie remained in the house alone until 1958, when Dr. Jackson and Richie Jean Sherrod moved in after their marriage. Dr. Jackson had joined the practice in the mid-1950s. Richie Jean was a cousin to Leola Whitted, the owner of the house, and would eventually inherit the home.

From 1958 onward, Richie Jean gradually added her own modern touches to the home's decor. The birth of Jawana Jackson in July 1960 brought further changes. It's important to note that very soon after The Jacksons moved into the home, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his colleagues became frequent house guests while visiting Selma College for seminars and lectures. By this time, Dr. King and the Jacksons had become close friends, and The Jackson Home was a safe haven.

In November 1964, Dr. King contacted The Jacksons about coming to Selma to expose the voting inequities happening there and asked if their home could be a planning base. The Jacksons quickly agreed, and Richie Jean redecorated, painting over the aging wallpaper and installing new carpeting throughout the house. Family photos of this period show these changes taking place, while the house’s exterior remained unchanged through 1965.

Artist’s rendering of The Jackson Home returned to its 1965 appearance. / Photo from The Henry Ford’s Experience Schematic Design Report

Artist’s rendering of The Jackson Home returned to its 1965 appearance. / Photo from The Henry Ford’s Experience Schematic Design Report

By 1967, the front porch’s wooden columns and crisscrossed railing were replaced with wrought iron. In the mid-1970s, the porch was further transformed into a brick half-walled space with a ceramic tile floor. The same brick was used to infill between the original piers and remodel the living room fireplace. Major renovations also included new drywall throughout the home, a remodeled kitchen, and the addition of a “lower den” family room. These changes, made after 1965, have since been removed to restore the home’s original 1965 appearance, with missing elements to be reproduced and reinstated to their original locations.

The front of The Jackson Home, circa 1963. This image shows the 1950s configuration of the front porch that remained intact through 1965. / THF708601

The front of The Jackson Home, circa 1963. This image shows the 1950s configuration of the front porch that remained intact through 1965. / THF708601

The front porch of The Jackson Home, Easter 1967, showing the recent addition of the wrought-iron railing and columns that replaced the wooden columns and railing. / THF718533

The front porch of The Jackson Home, Easter 1967, showing the recent addition of the wrought-iron railing and columns that replaced the wooden columns and railing. / THF718533

The Jackson Home has been part of many journeys. Among them are the lives of three generations, world-changing historical events and their aftermaths, a thousand-mile move from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan, and now, a journey back in time to 1965. Many of us have had the honor of being part of these last legs of the home’s journey, an honor we will not soon forget.

One half of The Jackson Home in its shipping container arriving at Greenfield Village and its two halves reunited on its new foundation. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

One half of The Jackson Home in its shipping container arriving at Greenfield Village and its two halves reunited on its new foundation. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

One half of The Jackson Home in its shipping container arriving at Greenfield Village and its two halves reunited on its new foundation. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford.

One half of The Jackson Home in its shipping container arriving at Greenfield Village and its two halves reunited on its new foundation. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford.

- Brown, Charles A. W.A. Rayfield: Pioneer Black Architect of Birmingham, Alabama, Gray Printing Co., Birmingham, AL, 1977.

- Durough, Allen R., The Architectural Legacy of Wallace A. Rayfield, The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 2010.

- Jackson, Richie Jean Sharrod, The House by the Side of the Road, The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 2011.

- Historic Structures Report, The Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson House, prepared by Quinn Evans, Ann Arbor, MI 2023.

- Van West, Carroll, and Richie Jean Jackson House National Register Nomination, Washington, DC: United States Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2013.

James R. Johnson is Director, Greenfield Village & Curator of Historic Structures & Landscapes at The Henry Ford.

*Batteries and Fuel Not Included: The Hop Rod, the World’s First “Powerized” Pogo Stick

Over the years many fun-but dangerous-toys have been marketed to children, only to be discontinued or banned. Remember chemistry sets with toxic materials? Or lawn darts capable of serious injury? Then there was the Hop Rod-a pogo stick powered by a combustion engine. Exploring the history of pogo sticks can help us understand the brief, explosive rise (and fall) of the Hop Rod in the early 1970s.

Early Hopping

Stilts were popular in 19th-century America for entertainment and recreation, and useful as tools for agricultural tasks. Among their early innovators was George H. Herrington, a bookstore owner from Wichita, Kansas, who held at least seven U.S. patents, including for a phonograph, fire escape, and typewriting machine. In February 1881 Herrington received a U.S.patent for his “spring-stilt” - a pair of wooden stilts with compression springs under each foot, intended to help users leap “great distances and heights.”

Illustration from U.S. Patent 238,042, issued to George H. Herrington of Wichita, Kansas, on February 22, 1881 / United States Patent and Trademark Office

Illustration from U.S. Patent 238,042, issued to George H. Herrington of Wichita, Kansas, on February 22, 1881 / United States Patent and Trademark Office

The Hopping '20s

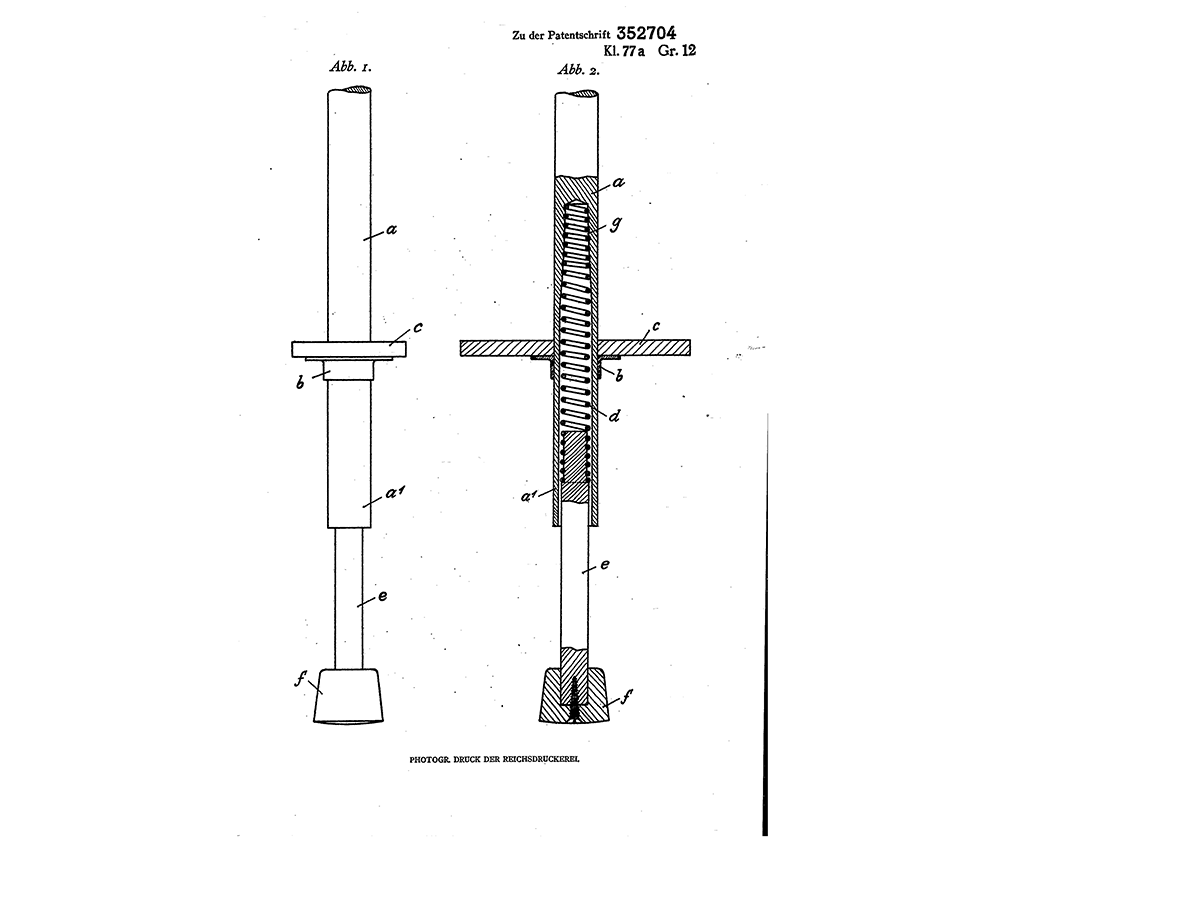

Fast forward to Europe. Germans Ernst Gottschall and Max Pohlig received a patent in 1920 for a "springy-looking hopping stuff." Unlike Herrington’s, it was just one stilt, with a spring mounted between the pole and base and a double footrest. The name “pogo” is believed to be derived from the first two letters of their last names—a common naming practice in Germany at the time. Around the same period, British inventor Walter Lines patented a similar vertical single-handled “hopping-pole."

An illustration from Gottschalk and Pohlig’s patent for the “Federnd wirkende Hupfstelze” (“springy-looking hopping stilt”), issued in Hanover, Germany, March 9, 1920 / German Patent and Trade Mark Office.

An illustration from Gottschalk and Pohlig’s patent for the “Federnd wirkende Hupfstelze” (“springy-looking hopping stilt”), issued in Hanover, Germany, March 9, 1920 / German Patent and Trade Mark Office.

As pogo sticks gained popularity in Europe, American sporting goods and department stores placed orders with overseas manufacturers. One New York City department store, however, received an order of pogo sticks that had mildewed and decomposed due to the damp conditions on the ship. Stores began looking for U.S manufacturers. George Hansburg’s SBI Enterprises in Ellenville, New York, started manufacturing pogo sticks. By June 1922, the word “pogo” was trademarked in the United States to refer to a jumping stick.

A 1920s pogo stick with a single vertical post, which could cause injuries to the rider’s chin. / THF805470 (left), THF805474 (right)

A 1920s pogo stick with a single vertical post, which could cause injuries to the rider’s chin. / THF805470 (left), THF805474 (right)

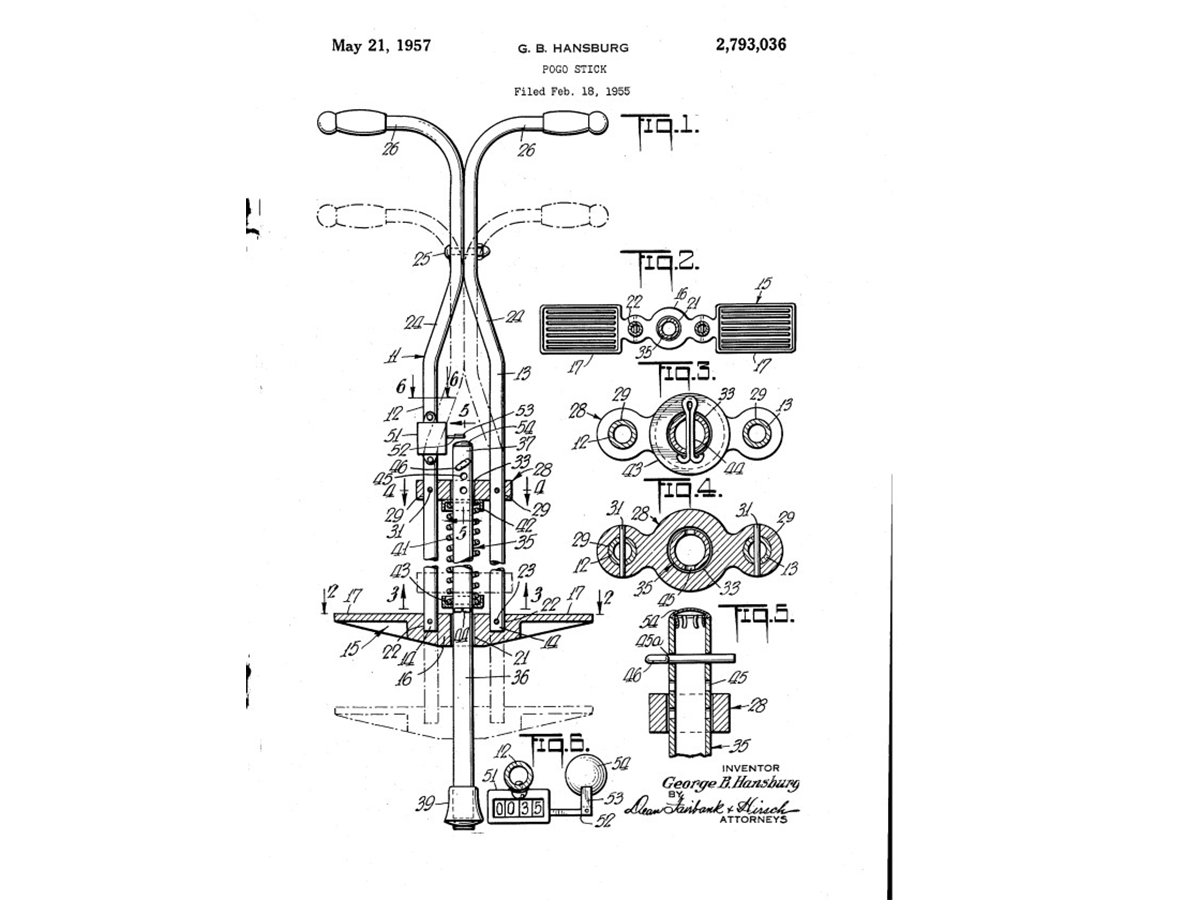

Though often credited as the pogo stick’s inventor, George Hansburg did not patent anything resembling a pogo stick in the 1920s. However, the United States experienced its first pogo stick boom in the 1920s due to the increased domestic production. Contests, races, and other pogo stunts popped up across the country. The Ziegfeld Follies even developed a stage show that featured performers on pogo sticks. Hansburg eventually redesigned the pogo stick – with double horizontal handles to reduce the risk of chin injuries from the vertical pole and received a U.S. patent for this improved design in 1957.

George Hansburg did not invent the pogo stick, but he helped improve it. This illustration of his patent from 1957 shows the horizontal handles that decreased incidences of facial injuries. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

George Hansburg did not invent the pogo stick, but he helped improve it. This illustration of his patent from 1957 shows the horizontal handles that decreased incidences of facial injuries. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

Adding Fuel to the Hopping Craze

The pogo sticks experienced a resurgence in the 1950s, becoming a favorite of the baby boom-era children hopping around suburban neighborhoods. It was during this time that Elwood, Indiana, farmer Gordon Spitzmesser had an idea: what if you added an engine?

Spitzmesser experimented with various designs, including combining the barrel of a grease gun with a piston from an old lawnmower and a Ford Model A spark coil. His son Edwin was his test jumper, trying out various fuel mixtures. Oxygen and acetylene resulted in intense jumps, but in the end, Spitzmesser settled on butane as the safest. In March 1960 Spitzmesser received a patent for a “Combustible Gas Powered Pogo Stick” which he called the “Pop Along.”

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

In 1961 Spitzmesser and his son appeared on national television. Edwin hopped around while his father explained the mechanics behind his invention. Although Spitzmesser never pursued mass production of his “Pop Along,” his patent was eventually acquired by Chance Manufacturing Co. of Wichita, Kansas.

The Hop Rod Takes Off

By 1971, Chance Manufacturing - best known for amusement park rides - began developing their own version of Spitzmesser’s design. After a year of testing, they released the Hop Rod, a pogo stick with a one-cylinder, two-cycle engine. It could run for up to 30 minutes - or approximately 600 hops - on four ounces of gas, preferably their proprietary blend called "Pogo-Go,"and eight C batteries. The Hop Rod activated when the rider's weight compressed the piston into the cylinder and activated the spark plug that fired the engine, launching the rider into the air.

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803604

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803604

Priced at around $70, the Hop Rod was marketed to parents and children, featured in commercials and local newspaper ads. Retailers across the country stocked the Hop Rod, including Young Diversified Industries in New Jersey and Midtown Cycles in Florida. Moto Pogo, Inc. in Vermont even offered a free electric popcorn maker (“Butterpopper”) with purchase in April 1973. The Hop Rod appeared at automobile shows, including the 17th Annual New York Automobile Show in New York City in April 1973. Newspaper articles of the time touted brisk sales, highlighting the Hop Rod as the hot Christmas gift in both 1972 and 1973.

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803610 (left),THF803607 (center), THF803611 (right)

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803610 (left),THF803607 (center), THF803611 (right)

But the Hop Rod was a shooting star - fast and flashy but too dangerous. Each engine “pop” produced increasingly higher jumps, sometimes beyond what the rider could control. The engine engaged upon impact with the ground - regardless of whether the rider landed vertically or at an angle - making it easy to be flung sideways into trees or other obstacles. Injuries followed, and the new gadget shine quickly wore off. By 1975, sales slumped, and Chance Manufacturing discontinued the Hop Rod.

Modern-Day Hopping

Although fuel-powered pogo sticks have vanished, pogo technology continues to evolve. Today's models use compressed air or solid rubber tube technology to absorb and release energy, enabling higher jumps and extreme tricks. Whether low-tech or high-powered, the pogo stick keeps on hopping into the 21st century.

The Henry Ford’s Hop Rod was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Aimee Burpee is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

George Balanchine and Ballet in America

If you are a fan of American ballet — be it regularly attending productions, seeing The Nutcracker at Christmas, or simply imagining what it would be like to be a prima ballerina — then you have likely engaged with the legacy of one of the dance world’s most important figures: George Balanchine.

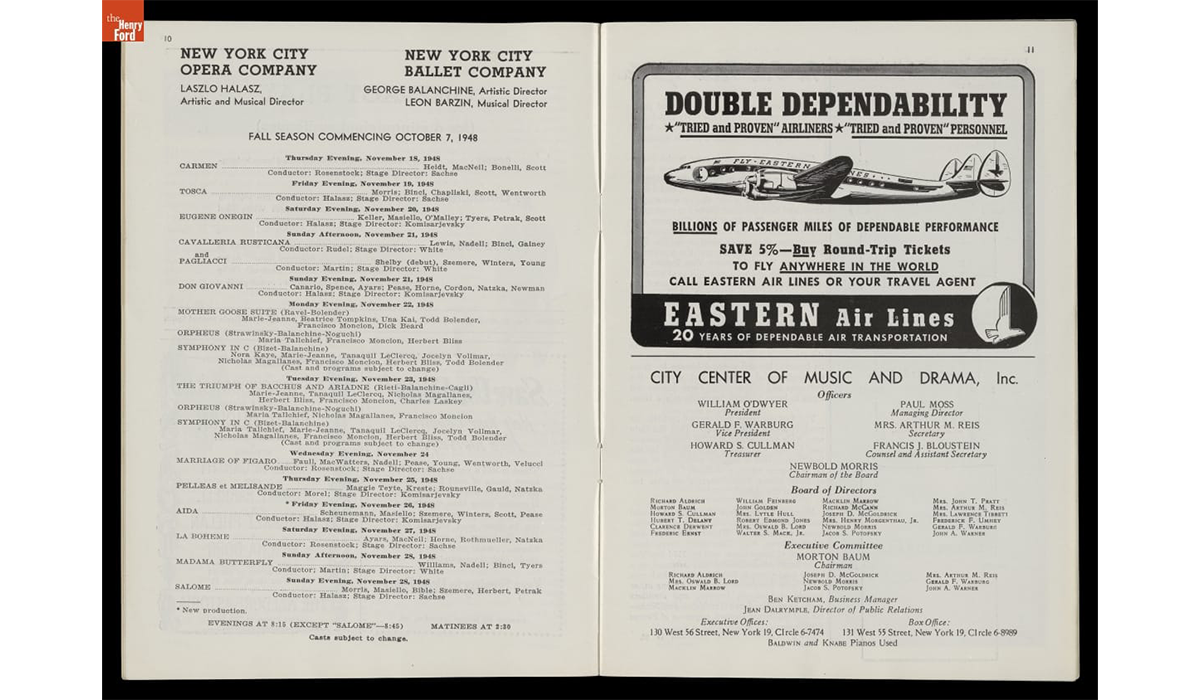

Program from New York City Center of Music and Drama, November 1948, featuring New York City Ballet’s schedule of Balanchine-choreographed performances / THF715566

Program from New York City Center of Music and Drama, November 1948, featuring New York City Ballet’s schedule of Balanchine-choreographed performances / THF715566

George Balanchine was born Georgiy Melitonovich Balanchivadze on January 22, 1904, in St. Petersburg, Russia. "He was exposed to the arts from birth, as his father was as his father was Meliton Balanchivadze, Georgian opera singer, composer, and founder of the Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre. His Russian mother, Maria, was also a lover of ballet, and although she thought her son would eventually join the military, she insisted that he audition for dance. At age nine, Balanchivadze was accepted into the Imperial Ballet School at the Mariinsky Theatre. Throughout his early years at the school, Balanchivadze already started to work on his choreography. In 1920 he debuted his first piece — a duet, La Nuit, which was met with some disapproval from his school's directors.

When Balanchine was born, ballet was seen as a way of rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg society. The city was the cultural center of Russia, and remained so throughout World War I (when it was renamed Petrograd) and after the October Revolution (when it was renamed Leningrad). / THF208535

When Balanchine was born, ballet was seen as a way of rising through the ranks of St. Petersburg society. The city was the cultural center of Russia, and remained so throughout World War I (when it was renamed Petrograd) and after the October Revolution (when it was renamed Leningrad). / THF208535

After graduating, Balanchivadze enrolled at the Petrograd Conservatory, and worked at the State Academic Theatre for Opera and Ballet in their corps de ballet, before forming his own ensemble, the Young Ballet. The Soviet government granted permission for the group to travel around Europe, and they eventually settled in Paris. In 1924, Balanchivadze was invited to join the famous Ballets Russes as the main choreographer, quickly being promoted to ballet master of the company. It was here that he changed his last name to Balanchine, and shifted his focus exclusively to choreography after a knee injury.

After the bankruptcy of Ballets Russes in 1929, Balanchine found work with other European companies, and continued creating new pieces. In 1933, American writer and cultural figure Lincoln Kirstein convinced Balanchine to move to New York City. With Kirstein’s support, Balanchine founded the School of American Ballet, opening its doors in 1934 with the aim of providing more rigorous training for American dancers. In 1948, Balanchine and Kirstein founded the New York City Ballet. It was for this company that Balanchine would create perhaps his best-known work - his version of The Nutcracker.

When Balanchine first created his version of The Nutcracker, he returned to the stage in the role of Herr Drosselmeyer. / THF360453

When Balanchine first created his version of The Nutcracker, he returned to the stage in the role of Herr Drosselmeyer. / THF360453

Although it was not the first version of The Nutcracker to be performed in America - that distinction goes to Willam Christensen's 1944 staging for the San Francisco Ballet — Balanchine's 1954 production helped cement the ballet's popularity, and indirectly ensured the survival of ballet in America. His version is distinct from others in that “Clara” is called “Marie” (her name in E.T.A. Hoffman's original story) and it maintains the tradition of casting children for the roles of Marie and Drosselmeyer's nephew (who is also The Nutcracker that becomes the Prince), rather than casting adult principal dancers as became common in other productions. Today, annual performances of The Nutcracker are what keep many American ballet companies afloat, with ticket sales for performances constituting approximately forty percent of their yearly revenue; it is Balanchine's version that remains the most popular staging.

Famed dancer Maria Tallchief — the first major American prima ballerina, and a member of the Osage nation — was lauded for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker. She is often credited alongside Balanchine with revolutionizing American ballet. / Seen here at top right, THF715558

Famed dancer Maria Tallchief — the first major American prima ballerina, and a member of the Osage nation — was lauded for her role as the Sugar Plum Fairy in Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker. She is often credited alongside Balanchine with revolutionizing American ballet. / Seen here at top right, THF715558

During his career, Balanchine founded several ballet schools, companies, and nonprofits. They include the previously mentioned School of American Ballet (1934-present) and New York City Ballet (1948-present), the American Ballet (1934-1938) which later joined with the American Ballet Caravan (1936-1941), and the Ballet Society (1946-present). Balanchine also served as the principal choreographer for Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo from 1944 to 1946.

In 1964, the Ford Foundation gifted almost $8 million to support professional ballet in America; nearly all of it went to Balanchine-affiliated companies. His choreographic work was prolific, as he created 400 individual works, many of which remain in the canon of ballet companies in America and abroad. He was also known for his choreography for Broadway and Hollywood productions, and for collaborating with the likes of composer Igor Stravinsky and designer Isamu Noguchi (who would continue working in the dance world by partnering with Martha Graham) for his productions.

For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, Ford Motor Company hired American Ballet Caravan to perform A Thousand Times Neigh, a ballet telling the story of the automobile through the eyes of Dobbin the horse. The dancers had been trained at Balanchine’s American Ballet. /THF215723

For the 1940 New York World’s Fair, Ford Motor Company hired American Ballet Caravan to perform A Thousand Times Neigh, a ballet telling the story of the automobile through the eyes of Dobbin the horse. The dancers had been trained at Balanchine’s American Ballet. /THF215723

Balanchine’s impact on ballet in America is almost impossible to overstate. Writing for the New York Times after his death on April 30, 1983, Anna Kisselgoff called George Balanchine “one of the greatest choreographers in the history of ballet ... [who] established one of the foremost artistic enterprises the United States has called its own.” The Georgian immigrant became known as the father of American ballet, as his choice to move beyond the classical style of his original training created a distinctly American style, one that rejected classical models and instead embraced artistic expression and dance for its own artistic and athletic sake, rather than as just a storytelling medium. This focus on athleticism and aesthetics, though, did not come without cost. Through his prolific work, Balanchine’s ideal dancer — long-legged and extremely thin — became the standard for American ballet. The pressure for ballerinas to be almost preternaturally thin persists to this day, and eating disorders and body dysmorphia are sadly not uncommon.

The story of American ballet — for better and for worse — is in so many ways the story of George Balanchine.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Youth Inventors Invent Sustainable Solutions to Global Challenges

Through The Henry Ford's Invention Convention Worldwide program, K-12 students identify a problem and work through the invention process to design a solution for it, and have the opportunity to present their inventions at local, state and regional competitions. While projects and topics vary, many inventors seek to tackle some of the most complex global challenges of our time, like climate action, cybersecurity, water scarcity and infectious disease.

At the culminating RTX Invention Convention U.S. Nationals competition, the top youth inventors from across the country pitch their inventions to judges and compete for awards and cash prizes.

Group photo from RTX Invention Convention U.S. Nationals 2025. Image courtesy of The Henry Ford’s Senior Photographer Jillian Ferraiuolo.

Group photo from RTX Invention Convention U.S. Nationals 2025. Image courtesy of The Henry Ford’s Senior Photographer Jillian Ferraiuolo.

What makes Invention Convention unique is that students identify the problem they wish to solve, providing for autonomy and greater engagement as they're solving problems they care about. Many look at the world around them and find they have potential solutions for sustainability problems that affect their home, their community or even the world at large. Here's a look at some of the award-winning inventions related to sustainability from this year's event:

- Incredapack, invented by Gwen Livingood, is a six-pack ring made from kelp that is meant to be a biodegradable solution to plastic six-pack rings polluting our oceans. For this invention, Gwen earned 2nd place in the 5th grade as well as the Environment and Sustainability Award, presented by the Avangrid Foundation.

- GroundLock - Preventing Agricultural Soil Erosion, invented by Grant Richmond, Zander Yang, Ashon Carter and Ravinath Boulton, is an innovative way to capture precipitation to redirect and store water on agricultural lands to prevent soil erosion. For their efforts, this Michigan team earned a Patent Application Award, presented by Cooley LLP.

- Reel Green Tackle, invented by Ian Klimowicz, is a biodegradable fishing lure and bobber that combats the effects of plastic fishing equipment that causes harm to wildlife and the environment. For this invention, Ian earned 3rd place in the 6th grade.

- ClearCrete, a Concrete Water Filter for Roadways, invented by Stepan Mkrtchian, provides a long-lasting, low-maintenance and effective water purification solution with applications in both urban and rural settings. This invention earned Stepan a Patent Application Award, presented by WilmerHale.

Gwen Livingood accepts the Environment and Sustainability Award, presented by the Avangrid Foundation, for her invention Incredapack. Photo by Nick Hagen.

Gwen Livingood accepts the Environment and Sustainability Award, presented by the Avangrid Foundation, for her invention Incredapack. Photo by Nick Hagen.

The team of Zander Yang, Ravinath Boulton, Ashon Carter and Grant Richmond accept their Patent Application Award, presented by Cooley, for their invention GroundLock. Photos by Nick Hagen.

The team of Zander Yang, Ravinath Boulton, Ashon Carter and Grant Richmond accept their Patent Application Award, presented by Cooley, for their invention GroundLock. Photos by Nick Hagen.

In addition to these projects, other sustainability-related inventions included:

- A biodegradable tennis ball to reduce the number of tennis balls that end up in landfills;

- Several inventions designed to help clean up trash from the beach;

- A robotic dog that would use AI sensors that would use AI sensors to detect and remove trash from hard-to-reach areas like forests, shallow canals etc.;

- A sustainable solution for removing oil from water using cactus powder;

- An artificial base for coral made out of eggshells to prevent further ocean acidification and global warming;

- And a device that would enable consumers to reuse scraps of paper, which doubles as a compactor and composter.

Invention Convention instills problem-identification, problem-solving, creativity and entrepreneurship skills for life, empowering students to become the inventors, innovators and entrepreneurs of tomorrow. We are continuously filled with hope for our future with these incredible inventors leading the way and we’re thrilled to see so many youth focused on projects that will help our environment.

All award-winners from RTX Invention Convention U.S. Nationals posing with RTX staff members and Aisha Bowe. All winners received a LINGO STEM kit created by Aisha and her team.

All award-winners from RTX Invention Convention U.S. Nationals posing with RTX staff members and Aisha Bowe. All winners received a LINGO STEM kit created by Aisha and her team.

To see a full winners list from RTX Invention Convention U.S. Nationals, click here.

To learn more about Invention Convention, please visit inventionconvention.org.

Samantha Rhoads, inHub Marketing Specialist